General Lucius D. Clay - The President's Man

by Richard F. Weingroff

On July 12, 1954, Vice President Richard M. Nixon informed the Governors Conference at Lake George, New York, of President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Grand Plan-a $101 billion program to create an articulated highway system, one in which the Federal, State, and local governments each assumed its appropriate role in financing and developing highways.[1]

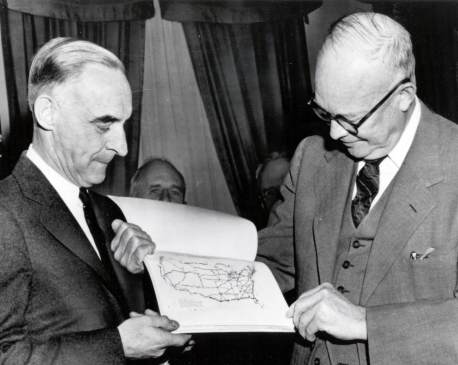

General Lucius D. Clay (left) shows President Dwight D. Eisenhower a detail from the Clay Committee's report. Photo courtesy of Eisenhower Library |

While asking the Governors for their ideas on how to accelerate the highway program, the President simultaneously launched his own initiatives to review the options for such a program. At the suggestion of Chairman Arthur F. Burns of the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA), the President established two committees on August 20 to explore the issues. First was an Interagency Committee of representatives from the Departments of Commerce, Defense, and the Treasury as well as the Budget Bureau and the CEA. Commissioner of Public Roads Francis du Pont was the chairman. The Interagency Committee would consider the economic requirements for a national road program and submit recommendations to the second committee established on that date.

The second committee, known formally as the President's Advisory Committee on a National Highway Program, was to work with the Governors and the Interagency Committee to develop a plan for submission to Congress. When Sherman Adams, the President's Chief Assistant, asked who should serve on the committee, the President said, "Call General Clay."

Lucius DuBignon Clay

Lucius D. Clay was born on April 23, 1897, in Marietta, Georgia, the youngest of the six children of Senator Alexander S. Clay. The Senator represented Georgia in the United States Senate from 1896 until his death in 1910. His youngest son entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1915, and graduated as an engineer in 3 years when the curriculum was curtailed following American entry into the war in Europe. His academic standing was 27th in a class of 137, but his discipline record was another matter. He was sometimes described, inaccurately, as first in academics, last in discipline. On June 12, 1918, the day of his graduation, he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant and, because of a shortage of officers in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Captain. The war ended in November 1918, before Captain Clay could reach Europe.

He married Marjorie McKeown, wealthy daughter of the president of the New England Button Company. Throughout his military career, Clay would serve with distinction--and live well--in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Beginning in 1933, Clay spent four years in Washington organizing and managing New Deal public works projects. In his childhood, Clay had spent considerable time in Washington, where his father was a friend of President Theodore Roosevelt. As a result, this assignment proved congenial, with Clay easily working with New Dealers and Members of Congress. In 1937, he was transferred to the Philippines, where he worked with General Douglas MacArthur and his chief of Staff, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

A year later, Clay became District Engineer at Denison, Texas, where he was in charge of design and construction of the Red River Dam. Before the start of World War II, Clay also directed a national defense program of airport construction. In 1940 and 1941, he oversaw the construction of 197 new airports in the United States, Alaska, and the Pacific Islands, as well as improving or enlarging 277 airports. He was promoted to Brigadier General in March 1942.

At the start of World War II, Clay was assigned to manage crash construction of 500 airfields. His work earned him a promotion to Brigadier General and a new assignment, chief of procurement for the U.S. Army. In that post, he procured 299 million pairs of pants, 50 million field jackets, 2.3 million trucks, 178,000 artillery pieces, 88,000 tanks, and billions of rounds of ammunition. In doing so, he earned the respect of official Washington. Secretary of State James Byrnes told President Roosevelt that given 6 months, Clay "could run General Motors or U.S. Steel." (A variation of this attributed statement was that Clay "could run General Motors or General Eisenhower's armies.")

General Eisenhower called on General Clay shortly after the D-Day invasion at Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944. With Cherbourg, the principal port of entry for supplies, snarled, Eisenhower asked Clay to untangle the flow. Clay doubled the flow in 1 day, and had supplies moving rapidly toward the front before leaving 3 weeks later.

Given General Clay's ability to manage a nation's resources, workers, and industrial production, General Eisenhower chose Clay to serve as Deputy Governor (1945-1947) of Germany. Clay served as Governor from 1947 to 1949. According to an account in The New York Times, he announced that his job was "to run Germany, not ruin it." The article added:

He told the Germans to stop feeling sorry for themselves, to cease grumbling and to get back to work.

After a series of conflicts with the Soviet Union, the situation in Berlin turned into a crisis on June 24, 1948. The Soviets blockaded all rail, highway, and water access to the city in an attempt to force the Western Allies to abandon Berlin. General Clay declared, "They can't drive us out short of war." With President Harry S. Truman's support, General Clay directed the airlift by 277,804 flights carrying 2.3 million tons of food and fuel to West Berlin that broke the Soviet blockade that ended on May 12, 1949. It had been the perfect match of man and mission. He was declared a hero in Germany and the United States, where he received a ticker-tape parade in New York City.

General Clay retired from the U.S. Army shortly after his return to the United States at the age of 52. He had earned a reputation as a "sharp-eyed, sharp-willed and tough minded officer," in the words of The New York Times. He was known as the "hero of Berlin." And there was one more thing. He was a descendant of the Kentucky statesman Henry Clay (1777-1852), who was known as "The Great Compromiser" for his efforts to hold the Union together while the debate over slavery threatened to pull it apart. As The New York Times put it: "A hundred years later, General Clay was to become known as 'the great uncompromiser.'"

The Clay Committee

Clay became Chairman of the Board of the Continental Can Company, which experienced a tripling of sales under his leadership, and a member of General Motors' board. He also became one of Eisenhower's most trusted unofficial advisors. Clay was influential in convincing Eisenhower to seek the presidency in 1952 and, after the election, shared the responsibility for identifying candidates for the Cabinet with Herbert Brownell, who would become Eisenhower's Attorney General. In addition, Clay provided advice and assistance to the President as desired.

With this background--training as an engineer, administrative and political skills, and trusted adviser--General Clay was a logical choice to help launch a program that President Eisenhower considered one of his highest priorities. It seems to be another perfect match of man and mission.

In a biography of Clay, Jean Edward Smith quoted an oral history interview in which General Clay recalled how he became involved in the President's Advisory Committee:

Sherman Adams called me down. This was in August 1954. We had lunch with the President, and they were concerned about the economy. We were facing a possible recession, and he wanted to have something on the books that would enable us to move quickly if we had to go into public works. He felt that a highway program was very important.[2]

In selecting members of the committee, General Clay's idea was that, "If we were going to build highways, I wanted people who knew something about it." He chose Steve Bechtel of Bechtel Corporation, Sloan Colt of Bankers' Trust Company, Bill Roberts of Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company, and Dave Beck of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. He chose them because, he said, "They knew what the highway system was all about" He added:

Steve Bechtel had more experience in the construction field than anyone in America. He wasn't involved in road building, but had a comprehensive knowledge of the construction industry. Bill Roberts built construction equipment; he knew what the problems were there. Mr. Colt was experienced in finance. We had to determine how we wanted to finance this, and so his experience was invaluable. And Dave Beck of the Teamsters certainly had an interest in highways, and he gave us labor representation.

All of them, Clay explained, were easily recruited. "They recognized that this was an important undertaking and they wanted to be part of it." The committee, however, would quickly become known simply as "the Clay Committee."

Although these men "knew what highways were about and how important they were," as Clay put it, none of them had been involved in the business of road building. Clay had rejected the suggestions he received from colleagues that he select such individuals as Robert Moses, the New York road builder, or a representative of the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO). He thought they represented "special interests" with preconceived ideas.

To make up for the deficiency in highway building experience, Francis (Frank) C. Turner of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) was appointed the Advisory Committee's Executive Secretary. Unlike the members of the Clay Committee, Turner was an expert in highway construction and finance after a career spent with the BPR, currently as Assistant to the Commissioner of Public Roads.[3] Turner would be the source of data, collected by BPR and provided to the Committee as it contemplated the scope of needs and ways of meeting them.

General Clay took the President's instructions seriously. The President wanted a financing plan that would satisfy Governors. This was one of Clay's chief concerns because the Governors had been on the verge of approving their annual demand that the Federal Government get out of the road building business when the Vice President delivered the President's Grand Plan message. The Governors wanted the Federal Government to abandon the Federal-aid program because they were convinced the State highway agencies could do a better job of road building without the meddling BPR looking over their shoulder. Further, if the Federal Government would abandon the gas tax, the States could pick up the tax without increasing taxpayers' costs.

President Eisenhower's decision to appoint two committees on the same issue was not unusual. He often relied on multiple, even competing groups to advise him on policy. In an oral history, Eisenhower said:

You must get courageous men, men of strong views, and let them debate and argue with each other. You listen, and you see if there's anything been brought up, an idea that changes your own view or enriches your view or adds to it.

In appointing two committees to study his "Grand Plan," President Eisenhower had chosen "courageous men, men of strong views." And he let them debate and argue with each other.

Eisenhower's two committees were to work independently. The general idea was that the Clay Committee would receive the Inter-Agency Committee's recommendations along with the proposals of other groups and individuals, particularly the Governors. Clay would then craft a program for the President to announce in January 1955.

The Interagency Committee quickly became enmeshed in internal debate. By November 1955, members were privately sending unsolicited memoranda to General Clay, hoping to ensure their views were received outside whatever compromise proposal the Interagency Committee might agree on.

The Clay Committee Goes to Work

As for General Clay, he had little interest in the Interagency's Committee's recommendations. He would develop his own plan after hearing what everyone else, including the Governors, had to say. He and the members of his committee soon found themselves confronted with the usual array of alternative plans and conflicting goals that had bedeviled debates on the National System of Interstate Highways from the start.

On October 7, in room 474 of the Executive Office Building in Washington, General Clay opened the first public session of the President's Advisory Committee on a National Highway Program. Before receiving testimony from the many groups awaiting their turn, he summarized the Clay Committee's purpose.

He said the President launched the current public debate at Lake George by suggesting a 10-year, $50-billion program, "over and above our present capital outlay," to bring the highway network up-to-date and meet population growth. Since then, Clay reported, the BPR had worked with State, county, and local officials, including AASHO and the Governors' Conference, to develop the 10-year estimate of highway needs called for by Section 13 of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1954. Preliminary results indicated that a total expenditure of about $101 billion would be needed over the next 10 years "to bring our highways in line with the anticipated traffic."

Under current programs, the revenues available over the next 10 years would be approximately $47 billion, leaving a deficit of about $54 billion:

Now, it is the reduction of this deficit with sensible financing that is the goal of this Committee.

The Committee was not going to question the need for the program:

We accept as a starting premise the fact that the penalties of an obsolete road system are large, and that the price in efficiency is paid not only in dollars, but in lives lost through lack of safety, and also in national insecurity.

Rather, the Committee would concentrate on organizing, financing, and executing the President's program. As Clay saw it:

The question really is not whether or not we need highway improvements. It is, rather, how we may get them quickly, economically, and how they may be financed sensibly and within reason.

Transcripts of the hearings on October 7 and 8 occupy several volumes and cover testimony from 22 organizations, but can be summarized in historian Mark Rose's words:

Farm leaders sought more mileage at less expense to their constituents, all without diminution of their own influence in local road-building affairs. Auto Club leaders argued for more attention to packed Interstate roads in urban areas, preferably by chopping farm-market construction from the federal payroll. Truckers, as always, wanted more roads built, provided only that taxes remained low . . . . According to one observer, "hearings which the [Clay] . . . Committee held . . . did not reveal any . . . consensus with respect to . . . finance." What it came down to was that "suggestions reflected . . . the interests of the group which the speaker represented."[4]

The Governors' Conference Special Highway Committee

Meanwhile, the Governors' Conference had appointed a Special Highway Committee, headed by Governor Walter Kohler, Jr. (Wisconsin), as requested by the Vice President, on the President's behalf, at Lake George. The other members were:

- Frank J. Lausche (Ohio)

- John Davis Lodge (Connecticut)

- Paul L. Patterson (Oregon)

- Howard Pyle (Arizona

- Allan Shivers (Texas

- Lawrence W. Wetherby (Kentucky)

Governor Robert F. Kennon of Louisiana, as Chairman of the Governors Conference, served as an ex officio member of the highway committee.

The Committee, minus Governors Lodge and Shivers, met with the President over lunch at the White House on August 10. Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks and Secretary of the Treasury George Humphrey were among the aides who joined the President and Governors for the discussions over lunch.

Following the meeting, Governor Kohler told reporters that he thought "an erroneous impression" had been left at the Governors' Conference that the Governors were hostile to the President's program. He said there was general agreement on the "compelling necessity of increasing highway building" and "the sooner the better." As for the $50 billion over 10 years, Governor Kohler indicated that this was not a hard and fast estimate. The final total might be higher or lower, with the majority of roads built as toll-free rather than toll roads. He added that such details as whether the Federal Government should get out of the gasoline tax field had not come up during the meeting with the President.

Governor Kohler said he believed the next move was up to the Committee. The members planned to send a questionnaire on highway needs and programs to all Governors. Based on the responses, the Committee would prepare a draft plan for approval by the Conference's Executive Committee. Governor Kohler expected the Committee to complete its report in November.

While in Washington, the Governors also met with AASHO President Alfred E. Johnson (Chief Engineer of the Arkansas State Highway Department) and Executive Secretary Hal H. Hale. The meeting, according to an editorial in AASHO's American Highways magazine, was "one of the most cooperative, serious, and determined sessions that one can imagine." In a 1972 speech, Johnson recalled that Governor Kohler was particularly concerned about construction time--he could get a State project underway in less than a year, while it took an additional year for a Federal-aid project. Governor Kennon invited Johnson to meet with the highway committee at the Governor's mansion in Baton Rouge, where Johnson helped overcome the Governors' objections to the President's program.

The Executive Committee of the Governors' Conference approved the report of the Special Highway Committee on November 30, 1954. Governor Kennon presented the report to President Eisenhower and General Clay in a White House meeting on December 3, 1955.

The Governors agreed that an adequate highway construction program was needed for the coming 20 years at approximately double the current rate of expenditures. To accomplish such a program, the Nation's highways should be divided into three systems--the Interstate System, other Federal-aid systems, and State and local systems. Based on data provided by the BPR from a pending report to Congress on highway needs, the Governors used an estimate of $101 billion for the cost of needs on all highway systems. Of this total, the Governors estimated that the Federal responsibility totaled about $30 billion over 10 years, including the cost of the Interstate System. Using the BPR's review of the cost of constructing the Interstate System by 1964 to meet 1974 traffic needs, the Governors estimated the cost to be $24 billion, of which about $13 billion would be expended in rural areas and the remainder in urban areas. Because the BPR estimate did not cover additional urban mileage, the Governors also did not cover this cost.[5]

Given the overriding Federal interest in the Interstate System, the Governors wanted the Federal Government to assume primary responsibility, with State participation, for financing its construction. The Governors suggested several funding options for financing the Interstate System, including general tax revenue, issuance of bonds, or a national road financing authority. More specifically, the Governors wanted to limit the States' share of costs to about $140 million a year, the amount they were contributing as their share of the cost of the Interstate System under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1954. On this basis, the Federal share of the $24 billion would be $22.5 billion, with the States contributing $1.4 billion over the 10-year construction period.

In addition, the States should, the Governors believed, be given "due credit" for the funds expended, either from public or toll road revenues, for construction of satisfactory sections of the Interstate System before the new program is approved. The States or their political subdivisions would be responsible for construction, maintenance, administration, and policing of the Interstate System.

What was absent from the Governors' report was a demand that the Federal Government stop collecting revenue from excise taxes on gasoline and other highway user products, a consistent demand of the Governors' Conference for many years. Because the States and localities would have primary responsibility for constructing all systems other than the Interstate System, the Governors "strongly recommended that the present federal excise tax rates on motor fuels and lubricating oils not be increased and that no other federal highway user taxes be levied." The report added:

[So] long as the national government levies excise taxes on motor fuels, lubricants and motor vehicles, it will continue to make allocations to the states for highway construction on the above other federal-aid systems, at least at the rate obtaining under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952 and in accordance with existing formulas.

This turnabout would not go unnoticed. On May 4, 1955, during hearings on the National Highway Program before the House Committee on Public Works, Representative Fred Schwengel of Iowa asked Governor Kohler about this change in position. Schwengel pointed out that for the past 10 years, the Governors had asked the Federal Government to yield the gasoline tax to the States. He continued:

I believe 2 years ago it was the unanimous opinion of the governors that that obtain . . . . Now, I think I see a complete flip-flop in this whole philosophy, where you are saying let the Federal Government stay in it. Do you realize when you are taking this position on this bill that you are committing the Federal Government to this gasoline tax for 30 years?

Governor Kohler responded:

Mr. Schwengel, we realize that this is the case . . . . I would like to point out that, so far as I know, the governors still, if polled, would adhere to their position as adopted at the Houston Governors' Conference in 1952, that the Federal Government should get out of the gas-tax field and leave that to the States.

The approach here is simply a realization of the practical political facts of life that the Government is not going to get out of that gas-tax field. So it is a question of relaxing and enjoying it, I think, rather than changing our minds.

Representative Myron George of Kansas, a former State highway official, interrupted to ask if the Governors' change of position was based on the fact that under the proposed program, all of the gas-tax revenue would be returned to the States for highway improvements, whereas before half the revenue went to the general treasury. Governor Kohler responded, "That is correct, Congressman George. That is correct."

Glenn E. Brooks addressed the turnabout in his history of the Governors' Conference. He observed that some of "the staunchest advocates of states' primacy" had left office by the time of the report, but even the remaining old guard Governors supported the increased Federal role in road building.

One conservative former governor, who was a key member of the special governors' highway committee, explained the reversal in an interview. Congress, he noted, was under heavy pressure to enact the highway bill with federal financing. The governors knew that the national government would not, indeed could not, get out of the gasoline tax field without wrecking the highway program. State legislatures were not strong enough to withstand the pressures that would be exerted by the oil and gas interests to cut the gasoline tax if the national government withdrew. In other words, all parties concerned--the president, the Congress, and the governors, knew that the national government was the only government politically and financially capable of levying the necessary taxes for the highway program.[6]

According to a news release issued on December 3 by presidential Press Secretary James C. Hagerty after Governor Kennon's visit to the White House, the President referred the Governors' recommendations to General Clay for study.[7]

General Clay's Plan

By this time, however, General Clay had already developed his plan for financing highway construction. Rose found that, amidst the swirl of competing plans, General Clay developed a program during October and November 1954 that met the criteria specified by President Eisenhower. The plan, developed in cooperation with the Governors, was consistent with the plan Governor Kennon submitted to the President.

General Clay had described the plan two days earlier, on December 1, at the 31st annual conference of the American Municipal Association in Philadelphia. After briefly describing his committee, General Clay stressed the importance of its work:

I would like to say first of all that we are fully cognizant of the fact that the entire economy of the United States is built on transportation and that we cannot visualize this economy continuing without transportation in all fields; rail, air, water and highway.

The Nation, he explained, had some 3.5 million miles of roads, over a million miles of which were still unpaved. Approximately 670,000 miles were eligible for Federal-aid under the current program. The "so-called interstate system" of 40,000 miles, authorized for designation in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 Interstate System, carries approximately 30 percent of all the traffic and "does provide the key network for intercity and interstate transportation." Although he felt the Nation was keeping up with roadway needs prior to World War II, that was no longer the case:

We had not anticipated a growth from 33 million registered cars and trucks in 1942 to 53 million registered cars and trucks in 1954 to an estimated 80 million cars and trucks in 1965 . . . . It seems without a shadow of doubt that we must have an accelerated road program to bring our road facilities in line with the growth of vehicles and vehicular ton mileage, estimated at approximately 800 billion vehicular miles per year by 1965.

Like the Governors' Special Committee, General Clay relied on the BPR's draft report to describe needs. Based on appropriate standards for the Interstate System, the Federal-aid primary and secondary systems, and other roads, the BPR "developed a total cost for road construction to meet these standards of $101 billion, which is of course a lot of money." He noted, however, that current Federal-aid, State, county, and municipal programs assured the Nation of a $47 billion construction program during the next 10 years. That left a balance of $53 billion "if all the roads of the country were brought to these standards. "Mind you," General Clay pointed out, "this includes rural roads of all types and kinds as well as your primary and secondary and the city streets of all types and kinds."

Given the adequacy of Federal-aid and State funding for the primary and secondary systems under current programs, the real "missing link" was funding to complete the 40,000-mile Interstate System. He used the same estimate as the Governors of the cost of the Interstate System ($23 billion plus $3 billion for "urban area feeder roads connecting the expressways." That was the amount, $26 billion, that constituted "the immediate and positive need."

Discussing whether a program of this magnitude is necessary, he offered three reasons. First, he cited national defense:

I don't like to blame everything on national defense because we have had a tendency in this country whenever we wanted to spend money to say it is a desirable thing from the national defense viewpoint; however, we cannot avoid the fact that this 40,000-mile system has been designated by the Defense Department as essential to national defense for the movement of both troops and supplies if war should come. We also know that in these days of atomic and hydrogen bomb warfare, if such warfare does develop, the problem of evacuation from centers of population . . . cannot be solved with the existing network of roads in the congested areas . . . .

General Clay's second reason was safety. Experience had shown that properly designed highways cut the accident rate, as much as one-fourth, over poorly designed and inadequate highways. Therefore, he said, "safety alone is a very convincing argument for an adequate road program."

Finally, he cited the economy. The population was expected to increase to 185 to 190 million people by 1965, when the Interstate System would be completed. By then, the vehicle population would be approximately 80 million cars and trucks. We must admit, he said, "that our present road system is inadequate to meet such demand."

In determining how to finance the $26 billion, the Clay Committee faced certain constraints. The Administration was committed to balancing the budget, so an increase in annual appropriations was out of the question. The Administration was reluctant to approve an increase in the national debt for a bond issue. Further, the Federal Government was embarked on a program of decreasing, not increasing taxes, so "we could not look to an increase in tax rates for the money to support this program."

The committee had only one other alternative, and that is the one adopted. Estimating that the present Federal tax on gasoline and lubricating oil raised about a billion dollars a year, with the amount likely to increase over time, the committee developed this concept:

Our tables indicate that a federal commission, authorized to issue bonds in its own name and promised a revenue equivalent to that which the government will receive from the gasoline and lubricating oil tax, with $550 million of that amount still appropriated for federal aid to primary and secondary roads, would support over the ten years a bond issue in the neighborhood of $23 to $24 billion, to be paid for over a 30-year period. And remember, these roads are being designed to meet the traffic of 1986 and with at least a 30-year life. In point of fact, with proper maintenance their life is indefinite.

As for the States, General Clay explained that their share of the cost of the Interstate System should remain at current levels. To match the current annual Federal authorization of $175 million for the Interstate System, the States were expected to contribute $140 million, "and in this enlarged program we think they should continue that contribution." He also thought the cities, which "would take advantage of the $3 billion program," should be required to spend at least as much money as they had contemplated spending for road construction during the 10-year period.

The problem presented by the toll roads also had been considered. The committee believed that where toll roads have been or are constructed, the State should be given credit for the funds so expended, with the funds from the Federal credit used to improve other types of roads. He felt the same idea should be applied where the States have constructed toll-free sections of the Interstate System to desirable standards.

General Clay acknowledged that his committee's financing proposal was unusual. "I doubt if such a proposal has been presented to the Congress before." But he added:

There is one thing certain, we are not going to get an adequate highway program through the normal approach. If we are going to have an adequate highway program, we have got to have the courage to take bold measures now so that it will be available when the traffic growth reaches us.

To develop the Interstate System, General Clay would establish a five-man commission, headed by the Commissioner of the BPR, to issue bonds, allocate funds, and "the working out of programs with the states based upon programs worked out in the states, between the states, the cities and the counties." No change would occur in the existing Federal-State partnership for the Federal-aid primary and secondary systems:

In such a way we believe a coordinated program would develop and for the first time we would have ten years to work on a program as a whole, the individual parts of which would fit into a real national highway system.

He summed up the Interstate portion of the committee's recommendation:

So perhaps we may say that we are recommending, rather than a pay-as-you-go policy, a pay-as-you-use policy, capitalizing the revenue of thirty years over and above the money required for primary and secondary roads so that we may have in ten years a really and truly national system of highways feeding our principal cities throughout the country.

On December 2, General Clay again outlined the proposal in Chicago, this time during a panel discussion on highway construction and financing, before the 12th biennial conference of the Council of State Governments. Just before the start of the 3-day conference, the Executive Committee of the Governors' Conference had met to approve the special committee's highway financing report. The Governors' plan was presented to the conference during the panel discussion. The following day, the assembly voted to support the proposal. The Associated Press reported that, "Gov. Pyle of Arizona, chairman of the assembly, estimated that the show of hands was 10 to 1 in favor of the stepped up road building."

The following day, General Clay reported on the program to the Conference of Mayors at the State Department Auditorium in Washington at 9:15 a.m. He began by acknowledging that in view of his speech before the American Municipal Association, "I'm afraid some of you have already heard the developments in this highway program."

Thus, as President Eisenhower accepted the Governors' proposal later that day at the White House and passed it on to General Clay for consideration, General Clay and his committee had already adopted the plan they would propose for the Interstate System.

The Clay Committee's plan was not only consistent with the Governors' proposal, but satisfied the President's demand that the plan be "self-liquidating"--although the President seems to have meant that phrase to refer to toll financing. It also did not add to the national debt, since the debt incurred by the five-man commission would be outside the Federal Government's accounts. Because the proposal was in addition to the regular Federal-aid program, it would provide the economic stimulus the President thought necessary to avoid what he called the "'peak and valley' experience" of the economy.

The plan also reached out to many of the competing interest groups. The Governors would find that the plan paralleled their own. Truckers would find that Federal excise taxes they paid would not be increased-tax revenue would increase automatically as traffic grew. Rural interests would find that the elements of the Federal-aid highway program would continue for their secondary roads. Urban officials would find that urban areas would receive funding. Congress could support the plan without increasing taxes. And the public would get what it wanted-better highways.

So the theory went. The reality would prove quite different.

Reaction to the Clay Committee's Plan

Newspaper reports based on the Philadelphia speech contained initial reaction to the plan, which had caused some confusion. The Detroit Times, part of the Hearst chain of newspapers that backed a big highway program, said, "Press dispatches state that Gen. Clay said the President's $50,000,000 program was being reduced about one-half because while the whole program was desirable, it was not feasible." Some listeners saw "a great reduction in the scope of the program." Attempting to clarify the proposal, Clay told the Hearst Newspapers:

It was never intended that the cost of the entire highway program would be borne by the federal government. I said in Philadelphia that while that might be desirable, it was not feasible. Obviously, there will have to be state participation in the President's program.

The Interagency Committee, its members divided as always, also were uncertain about Clay's plan. He urged them to endorse the plan without modifications; he thought any changes would hurt the proposal politically. His program had, he explained, sufficient incentives to guarantee support, unlike some of the ideas the Interagency Committee had been squabbling over. For example, any plan to use Federal-aid to construct toll roads would be "'whipped' before it got started." And charging tolls on previously free roads would lead to a "revolution" in the West. In fact, if the committee did not approve his plan without modifications, he would prefer that his plan not be forwarded.

Even the President had one reservation. In a meeting with Clay on January 11, 1955, the President expressed "tremendous enthusiasm," but asked why the committee had recommended gas taxes to repay the bonds instead of tolls, which the President personally favored. When Clay explained that tolls would work only in the heavily populated sections of the East and West Coasts, Eisenhower accepted the explanation. Overall, though, he thought the plan was consistent with his own interest in being able to regulate the economy. He wrote to Clay on January 26: "Our whole industrial activity [had to be] geared to a purpose of steady and stable expansion." Having the ability to avoid the "peak and valley experience" would allow the Nation to avoid "many serious and even unnecessary difficulties."

The controversy was not limited to the Administration. The Clay Committee's recommendations had gained "broad approval," according to the Engineering News-Record of January 20, 1955, but "there were barbed criticisms of specific details." Highway officials objected to the recommendation that the five-man Federal Highway Corporation would have a veto over the Commissioner of Public Roads. Officials were concerned the change would not only diminish the status of the Commissioner but "serve as an invitation to play politics with the interstate highway program."

And highway user groups objected to the proposal to repay States for construction of turnpikes or toll-free roads. As Engineering News-Record summarized the objection, "Highway users charged this would amount to making their membership pay twice for the roads they use most."

The Plan Moves Forward

As late as February 1, the Administration was still debating the merits of the Clay plan and alternatives to it. On that day, however, the debates came to an end (although some participants continued to favor their own concepts). During a February 1 meeting attended by Sherman Adams, Secretaries Weeks and Humphrey, and General Clay, among others, the issue of using tolls to finance the program was again raised. Historian Gary T. Schwartz summarized the meeting:

The discussion dealt partly with the political fact that a toll proposal predictably would arouse the ire of the AAA, state highway officials, and the state governors, particularly in the West; with these enemies, it was argued, the proposal would stand little chance of succeeding in Congress.[8]

In the end, Adams, representing the President, agreed with General Clay, and the matter was resolved.

The participants also worked on the President's transmittal message. Like so much involving the Grand Plan, members of the Administration had been divided on what approach to take. Should it be a general transmittal of the Clay Committee's plan or a discussion of the plan in detail? Should the report be transmitted as the President's views or merely as information to be used in shaping legislation. Perhaps the report should not be forwarded at all--the message would outline major points that were thought to be acceptable, with other points presented as alternatives. The issues were resolved during the meeting and the message drafted.

During this period, the President was preoccupied with the Formosa Straits crisis that erupted when the communist People's Republic of China appeared to be planning to cross the straits and attack the Chinese Nationalists on Formosa (now called Taiwan) over control of the islands of Quemoy and Matsu. In late January, the Congress approved a resolution authorizing the President, in advance, to engage in a war if he thought it best. The crisis, which would ease in late April, was one of the most serious foreign crises during President Eisenhower' two terms. Biographer Stephen Ambrose illustrated how serious by stating:

Indeed the United States in early 1955 came closer to using atomic weapons than at any other time in the Eisenhower Administration.

Nevertheless, the President took time from the foreign crisis to seek support from Members of Congress for his highway plan. In his mind, the two were linked. Ambrose states that:

Throughout the Formosa Straits crisis, [the President] had worried about how to evacuate Washington in the event of a nuclear attack on the capital, and on other cities too. Four-lane highways leading out of the cities would make evacuation possible; they would also facilitate the movement of military traffic in the event of war.[9]

On February 16, the President invited Clay to the White House to brief senior Republican Members of Congress: Senators William F. Knowland (CA), H. Styles Bridges (NH), and Eugene D. Millikin (CO), and Representatives Charles A. Halleck (IN), Joseph W. Martin, Jr., (MA), and Leslie C. Arends (IL). Although Clay conducted the briefing, the President stressed what he considered to be the important points: "With our roads inadequate to handle an expanding industry, the result will be inflation and a disrupted economy." He noted that recently built airports were already obsolete and "we cannot let that happen on our roads." Senator Bridges, however, warned the President and Clay that complaints were already coming from other Members about one element of the Clay Committee's plan, namely "windfalls" from reimbursements to States for roads already built.

On February 21, the President met with Democratic leaders of the Senate and House public works committees. He stressed that with 60 million vehicles soon jamming the Nation's roads, "we will have to build up our highways to meet that traffic. Clay's 10-year plan was "vitally essential for national defense" and was, in short, "good for America." Again, the Members raised concerns. Senator Albert Gore, Sr., the new Chairman of the Subcommittee on Public Roads, criticized the spending of $11 billion for interest on the bond. He argued, simply, "That money should be spent on roads."

The 10-Year National Highway Program

Whatever the concerns about prospects for the proposal, President Eisenhower forwarded the Clay Committee's report, a 10-Year National Highway Program, to Congress on February 22. The transmittal letter, drafted on February 1, began with a passage that has often been quoted as a summary of the President's views:

Our unity as a nation is sustained by free communication of thought and by easy transportation of people and goods. The ceaseless flow of information throughout the Republic is matched by individual and commercial movement over a vast system of interconnected highways crisscrossing the country and joining at our national borders with friendly neighbors to the north and south.

Together, the united forces of our communication and transportation systems are dynamic elements in the very name we bear--United States. Without them, we would be a mere alliance of many separate parts.

The Nation's highway system, he said, is "a gigantic enterprise" but "is inadequate for the nation's growing needs." The need for action was inescapable. He cited safety (more than 36,000 killed and a million injured each year on the highways at a cost of more than $4.3 billion a year), the poor physical condition of the roads (translating into higher shipping costs, about $5 billion a year, that are passed on to consumers), the need to evacuate cities in the event of an atomic attack (the present system would be "the breeder of a deadly congestion within hours of an attack"), and the inevitable increase in traffic as the population and the gross national product increase ("existing traffic jams only faintly foreshadow those of 10 years hence.").

The President described the Nation's highway systems, including the National System of Interstate Highways, the primary system and the secondary system. One thing was clear:

Of all these, the interstate system must be given top priority in construction planning. But at the current rate of development, the interstate network would not reach even a reasonable level of extent and efficiency in half a century.

After summarizing the key details of the Clay Committee's report, the President stated that a "sound Federal highway program, I believe, can and should stand on its own feet, with highway users providing the total dollars necessary for improvement and new construction." Financing of Interstate and other Federal-aid roads, therefore, should be financed by highway user excise taxes, "augmented in limited instances with tolls." All in all, though:

I am inclined to the view that it is sounder to finance this program by special bond issues, to be paid off by the above-mentioned revenues which will be collected during the useful life of the roads and pledged to this purpose, rather than by an increase in general revenue obligations.

Referring to the Clay Committee's report and the BPR's pending report on highway needs, the President concluded:

Inescapably, the vastness of the highway enterprise fosters varieties of proposals which must be resolved into a national highway pattern. The two reports, however, should generate recognition of the urgency that presses upon us; approval of a general program that will give us a modern safe highway system; realization of the rewards for prompt and comprehensive action. They provide a solid foundation for a sound program.

The President's phrase, "inclined to the view," would quickly suggest to critics that he was not committed to the financial proposal--the linchpin of the program.

The transmitted 54-page report by the Clay Committee summarized the President's Grand Plan speech, as presented to the Governors by Vice President Nixon at Lake George, and the formation of committees by the President and the Governors to meet the challenge.

The report stated that highway transportation--48 million cars, 10 million trucks, and a quarter of a million buses operating on 3,348,000 miles of roads and streets--is "by far the most comprehensive public transportation network in the world." The role of the automobile could not be denied:

In relatively recent years, the motor vehicle has come to occupy a unique place in America, not only because it is a major unit of transportation, but also because it is an intimate and seemingly indispensable part of our daily life. The bread winner uses an automobile to get to work; the housewife to shop; children ride in a car or bus to school, and the entire family relies on the automobile for many social and recreational activities.

Still, highways function as part of a transportation network:

All forms of transportation are essential to the national economy, including waterways, railroads, airways, and pipelines and their continued functioning as complementary services under equitable competitive conditions is important.

The report acknowledged the concerns of the railroads, which had pointed out to the committee that improved highway facilities were a competitive threat because they would result in increased truck haulage:

However, this Committee was created to consider the highway network, and other media of transportation do not fall within its province.

Before addressing the financial issues, the report summarized why highway improvements were needed. First was "The Traffic Jam," which could be reduced to its "simplest terms":

Traffic has expanded sharply, without a corresponding expansion in capacity of roads and streets.

"Simple arithmetic," as the report stated, illustrated why the Nation was experiencing "expensive, hazardous bottlenecks": 58 million registered motor vehicles driving 557 billion vehicle-miles in 1954. Prospects for the future were even worse--81 million vehicles by 1965 traveling 814 billion vehicle-miles.

Given the importance of highway transportation to the national economy, the expenditures called for, which may have seemed high, were necessary:

The increasing use of our highways contributes materially to the growth of our national product, since industry and employment directly related to the highway transportation system and its byproducts account for about one-seventh of its total value.

Moreover, the improvement of our highway systems as recommended herein would reduce transportation costs to the public through reductions in vehicle operating costs competently estimated to average as much as a penny a mile. Based on present rates of travel, this saving alone would support the total cost of the accelerated program.

Deterioration of the highways was another factor in support of the expanded program. Vehicle registrations and travel mileage were not the only increases; vehicle weights, average speeds, and axle loads were up, causing a serious deterioration of inadequately designed highways. The 4-year wartime moratorium on construction had taken its toll, but so had inflation:

While dollar expenditures for road construction increased in approximately the same ratio that their purchasing power has declined, the actual level of construction is not much higher than it was in 1940.

Safety must also be considered. The annual death toll on the Nation's roads was, as the President had pointed out, "comparable to the casualties of a bloody war." Replacing obsolete and dangerous highways with roads of modern design would substantially reduce the toll:

The death rate on high-type, heavily traveled arteries with modern design, including control of access, is only a fourth to a half as high as it is on less adequate highways.

For the Interstate System, civil defense issues were "of utmost importance." The report explained:

Large-scale evacuation of cities would be needed in the event of A-bomb or H-bomb attack. The Federal Civil Defense Administrator has said the withdrawal task is the biggest problem ever faced in the world. It has been determined as a matter of Federal policy that at least 70 million people would have to be evacuated from target areas in case of threatened or actual enemy attack . . . . The rapid improvement of the complete 40,000-mile interstate system, including the necessary urban connections thereto, is therefore vital as a civil-defense measure.

As General Clay had pointed out in his December 1954 speeches, the BPR's as yet unreleased report indicated that the Nation's total highway needs over the next 10 years equaled $101 billion, with present programs accounting for $47 billion of that amount. The report explained that closing the gap of $54 billion is the goal if highway transportation "is to perform its vital job in an expanding economy."

Responsibility for meeting the $101 billion in needs was shared by the Federal, State, and local governments. The Clay Committee estimated that the Federal share of these costs was 30 percent of the total. "The existing Federal interest in our 3,348,000-mile network of highways remains unchanged." Federal-aid for the primary and secondary systems would remain the same as in the past, although Federal-aid for urban routes would be reduced "because much of the work to be done with these funds as previously authorized is within the interstate system."

What had changed was responsibility for construction of the Interstate System. The Clay Committee recognized that the Interstate System, with an estimated cost of $27 billion (counting necessary urban-connecting arterials) over 10 years, "is preponderantly national in scope and function." Although the Federal-State matching requirements should remain the same--50-50--for other Federal-aid projects, Interstate projects should have an increased Federal share:

In the accelerated program, the States would be expected to contribute annually the amount they are required to contribute now to obtain funds from the $175 million made available to the interstate system by the Federal Government. The cities would be expected to participate to the same degree. This would make the cost of the 10-year program to the Federal Government about $25 billion.

To finance the Federal share of the Interstate System, the Clay Committee recommended creation of a Federal Highway Corporation as an independent agency of the Federal Government to finance the work "through a capitalization of appropriated funds in accordance with accepted financial principles." The corporation would have four purposes:

- Make payments to the States for construction of the Interstate System and approved arterial connecting routes or for projects undertaken by the Federal Government in the Federal domain;

- Establish a credit to any State that uses State funds, or funds under State control, to build Interstate segments, toll or nontoll, in designated corridors between 1955 and 1964;

- Finance administration, research, planning, and other purposes authorized by Congress; and

- Create a revolving fund to finance improvements pending receipt of payments;

For these purposes, the Corporation would issue bonds in an amount sufficient to complete the Interstate System during a construction period of 10 years. The Corporation, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, would determine maturity schedules, interest rates, and other conditions. The bonds would be secured by a contract between the Corporation and the Treasury Department to ensure the Corporation "will receive certain specified amounts annually as authorized by the Congress, always sufficient to meet its obligations." The report explained:

It is estimated that these amounts plus those proposed herein for continued allocations to the other Federal-aid highway programs, will be approximately equivalent to that portion of the receipts from Federal taxes on gasoline and lubricating oils.

No tax increases would be needed. However, as a precaution, the Corporation would have "a mandatory call" on the United States Treasury for loans up to $5 billion to ensure investors of the ability to meet obligations.

To administer the financial program, the Corporation would be managed by a Board of Directors consisting of three members-at-large, to be appointed by the President, while the Secretaries of the Treasury and Commerce would be ex officio members. On problems of location, the Secretary of Defense would also be an ex-officio member. The President would designate the Chairman of the Board, who alone would receive an annual salary and devote full time to the task. The Commissioner of Public Roads would serve as the Corporation's Executive Director.

All management responsibilities for the construction program would be vested in the Commissioner of Public Roads. However, the Board of Directors would serve as an appeals board when disputes arose between the BPR and the State highway agencies.

The report also discussed segments of the Interstate System that had been built to required standards by the States, either as toll-free or toll highways. The Clay Committee did not wish to discourage such construction since "our goal is maximum highway improvement." Therefore, credit would be given in varying percentages for roads built between 1947 and 1951 (40 percent of costs other than financing), prior to 1955 (70 percent of costs), and in 1955 or later (full cost). Credit should be provided only if toll revenue above costs is applied to other highway improvements:

The funds thus made available to the States will not only encourage matching of available funds but will also make possible accelerated improvement of primary, secondary, and other roads, and will encourage local financing of interstate mileage to make funds available for other roads without increasing total Federal responsibility.

The Clay Committee also addressed Interstate design issues. The number of lanes needed for the Interstate System would vary from two lanes (one in each direction) to eight:

Under the standards used in developing the program, approximately 7,000 miles of the Interstate system when completed to 1974 standard would remain 2-lane highways, but large sections would become 4, and in some cases 6- and 8-lane facilities to meet anticipated traffic volumes.

The report also commented on "Additional Urban Feeder Routes Needed," but did not clarify the type of routes it was describing or what standards might apply to them. The opening sentence of this section states:

Further to render the interstate system fully effective, it must be tied in much more closely with existing roads in congested areas. This will require provision for the major feeder and distribution routes which at present are not included within any of the Federal-aid systems.

Because the BPR had not estimated the cost of this mileage, the Committee examined this feature in several metropolitan areas. The review resulted in an estimated cost of $4 billion over the 10-year period. "This is intended to provide only for the most important connecting roads and is not intended to meet the total needs in this category." In testimony before the House Committee on Public Works in April, Clay would explain the urban component:

We have allowed $4 billion in this program for the improvement of the arterial routes connecting the cities with these expressways. White it is very true we want traffic to be able to go around the cities, also we want to have expressways connecting the cities themselves with this expressway, so that you can have instant access to and egress from the city. The figures with respect to these circumferential routes are not as good figures as we would like. Many of the cities have not made plans for the future. Therefore, within this $4 billion figure we have had to do a considerable amount of guessing. It is not as accurately engineered as the $23 billion.

My opinion is that it would go far to relieve the situation which exists today. It probably goes as far as the cities are ready to go. I doubt very much if in itself it would provide a complete answer to the city traffic problem.

On the basis of this limited review, the Clay Committee increased the cost of the Interstate System to $27 billion-and that would be the amount all parties were trying to reach while developing legislation for the 10-year construction program.

One of the keys to the success of these Interstate highways would be acquisition of sufficient right-of-way to permit control of access, which restricted the points of entry and exit to those designated by the highway designers rather than commercial developers. As the Clay Committee pointed out:

Otherwise, experience shows that the facility becomes prematurely obsolete due to developments crowding against the roadway which make it unfit for the purposes for which it was designed . . . . Present highway inadequacy results in part from the need to replace highways which have become unsafe and limited in capacity because of unlimited and uncontrolled access. We must not repeat such costly mistakes in the large investments which must be made now.

On a considerable portion of the Interstate highways, but especially in urban and suburban areas, relocating highway service onto a new location would be more economical than trying to control access along an existing roadway. Relocation would have the added advantage of allowing the highway designers to eliminate sharp curves on the existing routes, as well as reducing mileage between terminal points by selecting more direct routes.

Given the importance of control of access, the Clay Committee was concerned that State laws on acquisition of highway right-of-way presented "serious obstacles to the program." Congress was called on to enact legislation that would allow exercise of the Federal right of eminent domain where necessary and where requested by the State "similar to that authority now contained in the Federal-Aid Highway Act as related to the program of access roads for the national defense."

On some issues, the Clay Committee deferred to Congress. For example, utility companies had testified during the public hearings that they would incur "huge costs" in the relocation of utilities if the program were adopted. They urged the Federal Government to bear the costs. The BPR's needs report, which was the basis for the Clay Committee's data, had not estimated the cost of utility relocation, nor had the committee attempted to revise the estimates accordingly. The report, therefore, did not make any specific recommendation on the proposal "which is, of course, far reaching in its effects." This was a broad policy matter that should receive the attention of Congress.

The Clay Committee also took no position on motorist services, such as fuel and food. The turnpikes developed on the model of the Pennsylvania Turnpike provided services within the right-of-way, exercising a monopoly because motorists preferred not to pay toll to exit and re-enter the turnpike for a meal or to refuel at facilities beyond the interchange access ramps. The committee suggested that "care must be exercised to insure that traditional free enterprise is promoted and that no monopolistic tendencies develop in the provision of needed facilities to service the highway user with food, lodging, vehicle fuel, and similar needs." This problem required "careful thought and planning" by the Federal and State Governments as well as by private industry "so that equitable plans may be developed taking local requirements into account."

The report's conclusion contained a strong endorsement of the need for the President's Grand Plan.

We are indeed a nation on wheels and we cannot permit these wheels to slow down. Our mass industries must have moving supply lines to feed raw materials into our factories and moving distribution lines to carry the finished product to store or home. Moreover, the hands which produce these goods and the services which make them useful must also move from home to factory to store to home.

Our highway system has helped make this possible. We have been able to disperse our factories, our stores, our people; in short, to create a revolution in living habits. Our cities have spread into suburbs, dependent on the automobile for their existence. The automobile has restored a way of life in which the individual may live in a friendly neighborhood, it has brought city and country closer together, it has made us one country and a united people.

But, America continues to grow. Our highway plant must similarly grow if we are to maintain and increase our standard of living . . . . In fact, we face a challenge today and America has ever evidenced its readiness to meet a challenge head on with practical bold measures . . . .

Thus, we will accomplish the objective sought by the President for a "a grand plan for a properly articulated highway system that solves the problems of speedy, safe, transcontinental travel--intercity transportation--access highways--and farm-to-market movement--" . . . "paying off in economic growth--" . . . and making "a good start on the highways the country will need for a population of 200 million people."

If reaction to the Clay Committee's plan within the Administration was mixed, the reaction was even more divided among those who were seeing it for the first time. Rose summarized the reaction:

If those who stood to enhance their professional skills and reputations or fill their pocketbooks could live with most of Clay's package, others who would benefit little opposed it.

The Scripps-Howard newspapers included an editorial that called the proposal "the gold-brick scheme devised by the committee, which would hike the Federal debt without acknowledging it." An editorial cartoon depicted a talking "$101 Billion Road Program" carrying a hod of gold bricks labeled "Juggled Bookkeeping" and saying, "It won't be a debt-we'll just owe it." The Wall Street Journal, referring to "hocus-pocus bookkeeping," stated that this "bit of shenanigans" would be "a plain piece of pretense that a debt isn't a debt." The editorial also objected to the increased Federal role; after all, "the roads we now have were built by the cities, counties and states with but the smallest participation of the Federal Government." Building future highways was, certainly, "a stupendous job," but the Journal objected that claiming the need could be met only by "Federal planning and Federal taxes is to deny both our tradition of local government and the history of its success."

The New York Times supported the overall program but added that, "In a free society . . . the ends do not necessarily justify the means, and that seems to be the trouble here." The financing "will surely not be easy," but the report "treats this vital matter in a curiously offhand fashion." The editorial concluded, "In advocating such a blueprint for the nation's highways, the Administration has started down the wrong road." The Washington Post was more positive, calling the financing plan "a novel but reasonable way of undertaking such a capital investment." But the editorial shared the view expressed in a Herblock cartoon showing a crowded, dilapidated school as "U.S. Number 1 Construction Need" while President Eisenhower pointed in the opposite direction and showed Uncle Sam the "Administration Road Program."

Ominous Reception on Capital Hill

The reception on Capitol Hill was ominous. Support for the Interstate System was universal and bipartisan. But reaction to the financing mechanism was mostly negative. One of the chief critics was Senator Harry Flood Byrd of Virginia, Chairman of the Finance Committee.[10] Even before the plan was formally released, Senator Byrd reacted to early reports of the proposal by indicating his opposition to the financing concept, which he thought was "thoroughly unsound" and an attempt "to defy budgetary control and evade federal debt law." In addition to viewing the Clay Committee's proposal as a poor way to finance roads, Senator Byrd saw it as an unfortunate precedent:

If the government can borrow money in this fashion, without regarding it as debt and without budgetary controls, it may be expected that similar proposals will be made for financing endless outlays.

In short, he emphasized, "the bonds still would be debt," noting "you cannot avoid financial responsibility by legerdemain."

His views were echoed by other congressional leaders. They wanted the Interstate System, but they didn't like the idea that $11 billion of the funds raised by the sale of bonds-to be repaid with dedicated gas tax revenue-would go to investors rather than to roads. Senator Gore said, "It's a screwy plan which could lead the country into inflationary ruin." He had introduced an alternative on February 11 that would continue the existing Federal-aid highway program, but with $500 million authorized for the Interstate System annually through FY 1960. The Federal share would be 66.3 percent, with an increased share in States with large amounts of public lands and nontaxable Indian lands. Because the Constitution specified that revenue legislation must originate in the House of Representatives, the Gore Bill was silent on the origins of the revenue it would authorize, but Gore favored increasing the Federal excise tax on gasoline by 1 cent.

Senator Dennis Chavez of New Mexico, Chairman of the Senate Public Works Committee, said, "Personally, I'd like to build roads with the interest money instead of giving it to coupon clippers." Senator Francis Case of South Dakota, ranking Republican on the Subcommittee, expected "cautious and careful" consideration of the proposal, but thought the plan faced "hurdles." His counterpart in the House, Congressman J. Harry McGregor of Ohio, wanted to ensure the funds for "the greatest single peacetime construction program in world history" were "kept safe from any political game."

The President's program, in short, was in trouble from the start. Senators Case, Chavez, and Edward Martin (Pennsylvania) introduced the Administration's bill as a courtesy to the Administration. However, neither Chavez nor Martin actively championed the bill. Case would introduce an alternative bill in late March that called for a 90-10 Federal-State matching ratio, creation of a National Interstate Highway Right-of-Way Corporation to issue bonds backed by tolls and right-of-ways earnings, and increased user fees on heavy trucks and buses.

Equally devastating to the Clay Committee plan was testimony on March 28 by the newly appointed Comptroller General, Joseph Campbell, before Senator Gore's subcommittee. In Campbell's first congressional appearance since being confirmed, he stated that he found the financing method "objectionable" because it would not be included in the public debt obligations of the United States. Although supposedly not guaranteed by the Federal Government, the bonds would, as a practical matter, be supported because of the danger of default.

It is our opinion that the Government should not enter into financing arrangements which might have the effect of obscuring the financial facts of the Government's debt position.

He opposed the creation of new government corporations, which would be free from the normal controls over the conduct of public business and the expenditure of public funds.

During a March 30 news conference, the President was asked what he thought of Campbell's claim that the Clay Committee's plan "is unsound and, possibly, illegal." After commenting on Campbell's qualifications for the position, the President explained that he does not ask potential appointees what they will decide in specific cases:

If any man would pledge to me that he was going to make a certain decision because I asked him, he would never be appointed. So I have to concede to him his right to follow his own judgment and convictions. But I do tell you this, I think he is wrong.

General Clay Looks Back

Soon after releasing the plan, General Clay, the "Uncompromiser," gave an interview to Highway Highlights, a magazine published by the National Highway Users Conference. He was, he said, unfazed by the criticism. "If I had it to do all over again, I would not change one thing in our report. I would not add anything either." Clay said:

I knew, of course, that the report would be very controversial. However, it wasn't up to us to measure the controversy involved. It was up to us to give the President an exact report on what was needed-and how it could be achieved.

He had his eye on the goal:

I am firmly convinced that we need an accelerated road program. I am still for it no matter how it is financed. The main thing is to get the job done.

He explained that when he agreed to head the committee, his knowledge of the highway situation "was no more than that of the average motorist." He had to learn quickly and had formed some definite ideas about the essentials of a sound program:

One, that we commit ourselves to full improvement of the Interstate System over a specific period of time.

Two, that it be constructed to standards that will be required when the program is completed, rather than to present standards.

Three, that it be capable of being limited access throughout.

Civil defense, a major concern in the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, and national defense "would be full justification for doing the job. He didn't think any city could evacuate its population in 2 or 3 hours, although those with freeways, such as Detroit and Los Angeles, could do so more quickly than others. He saw, however, a more important justification for the program:

To me, the importance to the national economy of this modern highway system outweighs all other reasons why it should be built.

Without it, "the traffic will be almost unbearable." He explained:

All I can say is that 10 years from now we'll have 80 million motor vehicles-and we better have the roads. Because if we don't have the roads, we may not have the 80 million vehicles. And that, I think, would be very unfortunate for the whole country.

He added: "I think the public realizes it is in a traffic jam. I think it wants to see something done about it. Now is the time to do it."

End of the Line

As Congress took up consideration of the proposal, General Clay would testify in the Senate and the House. He defended the proposal forcefully, responded to all questions, and made clear that he did not share the doubts expressed about the proposal.[11] On May 2, he would tell the Nation's Governors, meeting in Washington, that he saw no reason to modify his proposal. He knew it would encounter difficulty in the Senate, he said, but he expected the House to approve it. It was not a "lost cause in any sense of the word."

Ultimately, however, it was a lost cause. The concerns about the financing plan would sink the Clay proposal. In 1955, after the Clay plan had failed in both Houses of Congress and the Congress had adjourned without passing a highway bill, writer Theodore H. White said the Clay Committee's proposals were born "out of the amateur ruminations of a number of civic-minded gentlemen enthusiastically exploring our needs over a period of a few weeks." What these gentlemen were about to find out, White observed, was a simple truism about roads:

For the politics of American highways has always been dominated by one overwhelming truth: everyone loves roads, but no one wants to pay for them.

Although the financing plan had been defeated, Clay's work had a lasting impact. The Clay Committee helped generate support for the President's highway goals and increased the pressure on Congress to do something about it. In addition, the BPR data in the Clay Committee's report provided the statistical backing for the program as well as the target-$27 billion-Congress would set as its goal in finding a way to finance construction of the Interstate System.

Clay would play no further role in the debates or development of the Interstate System. As biographer Smith pointed out:

His task had been to design and create a national highway net. Which he had. "When something is over, it is over," Clay often said . . . . After the interstate program was passed by Congress, Clay had left the transportation field to others. In later years, he had mixed feelings. He was deeply committed to America's economic development, but recognized the problems the automobile created. There were no easy answers.

He was asked if he had any second thoughts:

In the original program, we did not include provisions for expressways through cities. That was added later. It greatly increased the cost of the program, and it is these expressways that are not very popular today. Although, there again, a city doesn't want to be bypassed either. I'm not really sure what the answer is with relation to our big cities and the freeways. However, I am sure that the Interstate System was well designed. It is proving that in the way it has served our transportation needs ever since.

Later Years

General Clay would remain a trusted advisor to President Eisenhower through the end of his second term, and would provide a similar service to his successor, President John F. Kennedy. The new President appointed Clay to a committee that accompanied Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson on a journey to Berlin in August 1961 to reassure the German people of continued American support in the face of increasing Soviet pressure. Clay, still known as the "Hero of Berlin," was appointed the President's personal representative to the city, with the rank of Ambassador, serving from September 1961 to May 1962.

In early 1963, the President again turned to Clay, this time to head a 10-member committee to study the foreign aid program. It concluded that the country was trying to do "too much for too many."

After reaching the mandatory retirement age of 65, Clay left Continental Can Company in 1962

The following year, he became a senior partner in Lehman Brothers, an investment banking house. From 1965 to 1968, he chaired the Republican Party's Finance Committee.

From his home in New York City, he was active in local affairs. In 1966, Mayor John V. Lindsay appointed him to head a Public Development Corporation to revitalize the city's industry. Later, he served on the City Charter Revision Commission. During a November 1972 while on the commission's bus tour of the worst areas of the Bronx, he commented, "It makes you feel helpless; why I saw the Germans take bombed-out cities and completely restore them in 10 years."

Clay died in Chatham, Massachusetts, on April 17, 1978, at the age of 80. His obituary in The New York Times, commented:

General Clay was a man of unmistakably military figure. His manner was decisive, he made quick decisions, he spoke with authority and assurance and he expressed himself in terse, clear statements. In war and peace, in the Army and in business, he was known as one who could get things done . . . .

The general's powers of concentration were remarkable. He could work as well amid the clatter of typewriters and the jangle of telephones as in the quiet of oak-paneled carpeted rooms. At the drop of a helmet liner he could speak on foreign affairs, civil defense, and the menace of Communism, the state of business or the state of the nation. And when he accepted an invitation to speak, he rarely prepared a text. He did not have to, because he had a phenomenal memory for a wide range of facts . . . .

General Clay's soft voice and courteous manner did not entirely hide a stubbornness and a capacity for occasional bursts of temper. After a hard bargaining session, a high British officer once said of him: "He looks like a Roman emperor-and acts like one."

General Lucius D. Clay was survived by his wife Marjorie, two sons (General Lucius D. Clay, Jr., of the Air Force and Major General Frank B. Clay of Army, both retired), seven grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. Clay was buried at West Point.

Notes:

The speech is available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/rw96m.cfm. [return to text]

Smith, Jean Edward, Lucius D. Clay: An American Life, Henry Holt and Company, 1990 [return to text]