| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |

The Trailblazers

Forty - Six Years with BPR

By

Clifford Polk

I started with the Bureau of Public Roads in 1916, at a time when very few people were in the organization. B. J. Finch had come out from Washington DC, in 1914 to take care of Forest Service road work, and John Paul, an engineer, was assigned to assist Skamania County, Washington, on county roads. In 1917, the Bureau was divorced from the Forest Service and Dr. L. I. Hughes came out from Yale University to organize the Portland Office field staff. We primarily did reconnaissance surveys in those days; there wasn't much construction going on yet.

The first project I was on was the McKenzie Highway in Oregon. We made a survey from the lava beds at the crest of the Cascade Range to the McKenzie River bed. Our survey party included Ben Beazley - chief, an instrument man, two temporaries from Eugene, and me - as a deck hand. We stayed at a Forest Service camp and hiked six or eight miles to the lava bed to make the survey. We had to go in with a pack string in the snow as the elevation was pretty high. The McKenzie Highway is still in existence, although not used very much.

In 1919, road construction, rather than just survey work, began to hum and the Bureau personnel roster expanded. In 1922 to 1926, the amount of work dropped to only three or four construction projects in each State because of lack of funds and equipment. Consequently, we laid off our field crew in the winter.

When I look at the roads we're building now, I'm ashamed of some of the one we built in the early days. A lot of our early roads were just dirt; the lucky ones got crushed gravel. It wasn't until 1931 that we got oil type surfacing. We'd shoot oil on gravel or crushed rock and put on another layer or rock screening. The oil would seep up and give a fairly hard surface. When we used concrete, we'd just find a gravel bar and mix that with our cement - we often followed no real standards and did little testing. Now, everything is weighed and measured in right proportions.

In 1925 we took over road work for the Park Service and Mr. Kellogg took charge of road engineering in Rainier Park. The depression provided a boom for BPR because funds were increased to provide jobs. I had a WPA job in Rainier Park - the work was done by contract but the contractor had to hire unemployed people sent out by WPA county officials, except for such key positions as foremen and highly skilled laborers. The common and skilled laborers could only work 40 hours a week at 50¢ an hour and had to pay $1.05 daily for board. Nobody starved, but nobody got rich either.

On the Rainier Park project, we all camped at Ohanapecosh Hot Spring. I was allowed to camp in the park with my family and the park bears would come up regularly to beg for food. We fed the, and I guess that made them more bold because one day I woke up early to see a bear poking his head through the tent window, within reach of my daughter. I scared him off before he caused any trouble though.

I remember another incident with an animal which took place when another fellow and I were doing a reconnaissance survey over the Blue Mountains. We picked up a packer and came in on an old dirt road which followed the Union Pacific Railroad. We slept out in the open and I used a coat folded on top of my shoes as a pillow. One night I woke up at the sensation of something eating my head. I jumped u in time to see a porcupine run off into the woods - he had been eating my shoelaces!

In 1942 I was offered a job on the Alaska -Canadian Highway (Alcan Highway), an important, rush, 1,500 mile highway project designed to link up the continental U.S. to Alaska. The need fro such a highway has surfaced because Japanese subs in the Pacific Ocean were threatening our supply route by sea to Alaska and other routes were, and still are, extremely important for that area.

I was in charge of a section from Fairbanks to the Canadian line, and when I arrived with my planning crew, we found that someone had goofed and sent up a boat load of engineers and equipment a month early. They had arrived before we had, and had gotten the Army to feed them.

We were allowed to buy and hire whatever we needed due to the importance of the highway. Most things we had to order out of Seattle and wait until they were shipped to Valdez. All orders came late. If it hadn't been for a huge mining supply store in Fairbanks, we'd have been sunk. Fortunately, mining in that area had slowed up at the beginning of World War II and this store had stockpiled a large inventory of equipment. We also had two men who did nothing but scout around the State for used equipment from abandoned mines.

The worst thing about Alaska was the lack of transportation. There were hundreds of miles of wilderness with no roads or even trails. Our supplies and materials came in by boat up the Tanana River or were dropped from airplanes - without parachutes! We often received things broken up, needless to say.

One great snafu occurred when a contractor brought up 1,000 men to work on the highway. They arrived before any of their gear or equipment did and had to be crammed into a hotel that was built to hold 100 people! The hotel had to serve meals around the clock to feed the 1,000 men.

The U.S. Army was supposed to help us by bulldozing a clearing through Alaska which we were supposed to follow. We ended up getting ahead o them because their equipment kept breaking down and their mechanics weren't good enough to keep it running. Towards the end, we did our own clearing and grading and our standards were higher than the Army's.

We worked until December when the weather dropped to as low as 40 degrees below zero. The contractor and his 1,000 men had left a little earlier but were stuck in Valdez for three weeks waiting for their ship to come get them. We flew from Fairbanks to Whitehorse (in the Yukon) for the winter. I went to Haines, Alaska, for a while to work on plans for a road from there to the Alaska Highway. We had trouble getting out of Haines because we had to cross the sound by boat in freezing weather to get the train back to Whitehorse. We crossed in a small boat and one man did nothing but cut off the ice as it formed on the boat. The waves were huge and we couldn't see a thing, but we managed to cross the sound. That was the worst boat trip I ever made!

After the Alcan Highway was completed, things were pretty dull. Money was going into the war effort rather than roads, and most men were in the service. I sat around pinch-hitting in the Portland office, occasionally inspecting projects in Washington. I became the assistant to the Division Engineer and when we located an office in every State capital, I went to Salem, Oregon, and later headed the office there. Sometimes conditions were pretty rough physically, but always enjoyable.

Forest Highway Projects, 1916 My first job - June 1916, McKenzie Highway survey crew at our campsite. From left to right: a temporary from Eugene, Cliff Polk, a medical student temporary, Arthur Clark, and Ben Beazley |

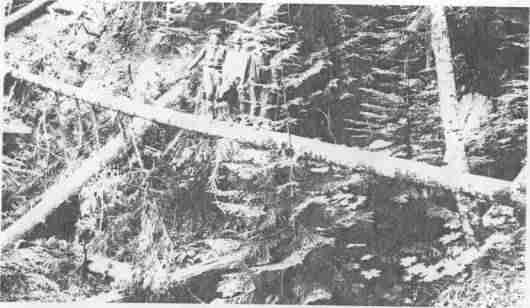

This is the type of country we had to walk through to get to work. Alaska, 1943

Completed section of the Highway east of Cathedral.

A couple of my top men taking a ride.