U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Highway Infrastructure Security and Emergency Management Professional Capacity Building

Download Alternate Versions:

slide 1

Speaker Notes:

This briefing was researched and produced as a project by Excalibur Associates, Inc. in support of prime contractor SAIC under Federal Highway Administration Transportation Pooled Fund Study 5(161), Transportation Security and Emergency Preparedness Professional Capacity Building (PCB) Pooled Fund Study. State Departments of Transportation and other agencies contributing to the pooled fund were California, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, Montana, New York, Texas, Wisconsin, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Transportation Security Administration.

Representatives of contributors to the Pooled Fund agreed that a general briefing was needed to inform supervisors and managers, especially those that perceive they have no security and emergency management responsibilities of the roles, missions, organizational structures, plans, concepts, and terminology used by the security and emergency management community.

This briefing is directed at newly assigned managers and supervisors, those that have had no security and emergency management training, or those in need of refresher training. It is recommended that all managers and supervisors view this briefing to ensure they are aware of the information provided and the possible impact on them personally, their office, and their staff. If you prefer to look at this briefing offline, or keep it for reference, it might be more convenient for you to print the PDF version.

slide 2

Speaker Notes:

As a supervisor or manager in a State Department of Transportation (DOT), you may occasionally hear terms that appear to have nothing in common with your office's day-to-day responsibilities; terms such as:

You may have wondered: What are these things and what impact do they have on me and my office?

The purpose of this briefing is to inform supervisors and managers of roles, missions, organizational structures, plans, concepts, and terminology used by Government agencies at all levels and by the private sector in preparing for, responding to, and recovering from emergencies or disasters.

The intent is to provide sufficient information to allow those that go through the briefing to enable them to ask questions and explore their roles or the roles of their offices or staff in emergency management activities.

If you desire more information about any of the terms or concepts, there is a list of references at the end of this briefing.

slide 3

Slide Notes:

The role of DOTs in State response operations is evolving. DOTs are assuming a larger role in planning and preparing for response and recovery operations, whereas in the past they usually reacted following an emergency. They now work more closely with the State Emergency Management Agency and other partner agencies on a routine basis prior to as well as during disasters and emergencies. State DOTs are participating more often in statewide training and exercises to become better prepared to execute response operations.

It is important for you to understand that during response to and recovery from emergencies, you, your office and members of your staff may be required to perform other than your normal duties in an organizational structure unlike your day-to-day structure, and working for a supervisor that is not your day-to-day supervisor.Likewise, because of your expertise, you may be called upon to lead or supervise a team made up of individuals relatively unknown to you.

This briefing is aimed at helping you understand concepts so you can effectively communicate during these times.

slide 4

Slide Notes:

There are two parts to this briefing.

First, Information You Should Know. This takes up the majority of the briefing. The information is presented as an overview to acquaint you with various aspects of emergency management, but is not intended as a complete discussion. You are encouraged to do independent research which will require you to ask questions of your DOT Emergency Coordinator.

With an understanding of the information presented, the remainder of the briefing is intended to generate questions that will cause you to seek out additional information that is specific to your State DOT:

slide 5

Slide Notes:

Let's begin with a discussion of information you should know.

slide 6

Slide Notes:

What is emergency management?

Emergency management involves preparing for a disaster or emergency before it occurs, the response actions taken during a disaster or emergency, and recovering from or rebuilding after a disaster or emergency has occurred.

The Emergency Management Process

Stated in another way, emergency management is the continuous process by which all individuals, agencies, and levels of governments manage hazards in an effort to avoid or reduce the impact of disasters resulting from the hazards. There are four (4) phases:

slide 7

Slide Notes:

Your State DOT has a role in all four (4) phases of emergency management.

In terms of time, response is relatively short, whereas recovery can take years depending on the extent of damage.

slide 8

Slide Notes:

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has a hazard mitigation assessment and planning process for local officials to use to conduct hazard assessments and create plans for mitigating the hazards.

It is important that these assessments and plans include transportation infrastructure. Funding for transportation infrastructure mitigation will normally come from sources other than FEMA resources. Transportation infrastructure should be integrated into overall hazard mitigation assessment and mitigation plans because of the interdependencies of transportation infrastructure with non-transportation infrastructure such as highway bridges carrying communications lines or rail lines carrying fuel for power plants.

Mitigation of transportation infrastructure may occur under the oversight of the State DOT, depending on the State and the type of infrastructure. In most cases, it will be done by private contractors, but under contracts managed by the State DOT.

slide 9

Slide Notes:

Hazard Identification

The first step in preparing is identifying the threats and hazards that a State faces. This step provides the answer to the question: What is the basis for the plan? For example, Southern coastal states are particularly vulnerable to hurricanes, while Midwest states are vulnerable to floods and tornadoes, the West Coast and Midwest must plan for earthquakes, and most Northern states face severe winter storms. All states face the threat of terrorist or criminal caused incidents and accidents causing chemical spills or contamination from nuclear power plants.

The State DOT responsibility is to identify hazards and threats facing the State's transportation infrastructure. Transportation infrastructure is particularly vulnerable to a variety of hazards and threats, including:

slide 10

Slide Notes:

Planning

Governments take an all-hazards approach when planning. Response activities tend to be the same regardless of the event – life-saving, minimizing damage to infrastructure, caring for peoples' needs. However, because there are small differences depending on the specific hazard, States develop plans describing how they will respond to the affects of particular hazards/threats when they occur.

States plan to support local government response efforts because initial response occurs at the local level and local governments do not have extensive resources to support response operations. States also plan to support other states. No State agency can respond completely independent of other organizations and preparedness efforts must be coordinated between agencies.

States also need to plan to receive and use resources provided by other States and the Federal government during response operations. Planning is an integrated and coordinated process, vertically and horizontally:

The State DOT will coordinate planning efforts with other State agencies, including the State's Emergency Management Agency; county highway departments; with various agencies of the U.S. Department of Transportation; and, with DOTs from other States to ensure response activities can be easily integrated when necessary.

slide 11

Slide Notes:

Training

Once the plans are developed, individuals and teams need to be trained to execute the various aspects of the plan. Generally, individuals are trained in their tasks, then teams are brought together to train on integrated tasks.

Training may be classroom, at the DOT or another location; on-line through the Federal Emergency Management Agency or other organization; or may occur on the job to build depth in an Emergency Operations Center (EOC).

Exercising

Exercises are controlled activities conducted under realistic conditions to provide an opportunity to test one or more parts of response plans. They are also used to validate the effectiveness of training of individuals and teams. Exercises are conducted prior to real events so results can be examined in depth to determine what changes, if any, need to occur.

After Action Improvement

Information is collected during and following actual response operations and exercises to determine how well the plan worked and what future training may be needed. The planners take the information, analyze it and make changes to plans and training curricula to ensure better response operations in the future.

slide 12

Slide Notes:

Emergency Operations Plans

Once threats and hazards have been identified, plans can be written. Plans generally address the areas of:

All levels of government – local, tribal, State and Federal – as well as their departments and agencies, prepare formal Emergency Operations Plans (EOP) to establish responsibilities, authorities and procedures on how the entity or organization will operate in response to an emergency or disaster. Your State may call it an Emergency Response Plan, but it is the same thing.

Operations or response plans address:

slide 13

Slide Notes:

Response activities need to occur as quickly as possible following an event if lives are to be saved and damage to infrastructure minimized. While these activities generally occur first at the local government level, State agencies and their personnel need to be prepared before an incident so they can provide resources and support to those local governments.

Tiered Response

Fire departments, emergency medical units, and police respond to incidents; local government agencies mobilize to perform activities within their sphere of responsibility; local organizations establish care centers for displaced residents. States and their agencies mobilize to provide resources: material, equipment, supplies, personnel, or funds to the local government and its agencies, if necessary. The Federal government agencies mobilize to be ready to provide support to States if necessary.

Scalable and Flexible

The level of effort during response operations waxes and wanes depending on the level of activity needed at any given time. At the onset, there may be a large amount of activity at the local, State and Federal levels. Once life-saving activities have been accomplished, resources are directed towards caring for displaced people and cleaning up. Then, in later stages, rebuilding begins to occur, which requires less response personnel and more resources, usually from State and Federal levels.

Unity of Effort

Response activities need to occur in a fully integrated and seamless manner to endure the most efficient and effective use of resources. This occurs through Unity of Command – local, State and Federal leaders work together to bring resources to the point where they are most needed.

Let's look at several documents that further describe these concepts:

slide 14

Slide Notes:

The National Response Framework (NRF) was published in January 2008 by the Federal government, with input from partner stakeholders: Federal agencies, States, local response organizations, and the private-sector. It is a guide to how the Nation - local, tribal, State, and Federal governments, and the private sector - conducts all-hazards response. It provides guidance on how roles are aligned for efficiency and effectiveness during response operations. It is based on best practices identified following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and describes specific authorities and relationships for managing incidents that range from the serious, but strictly local, to large-scale terrorist attacks or catastrophic natural disasters. It is not a response plan, but provides a basis for developing response plans at all levels of government.

A critical principle of the NRF is all incidents are managed locally.

The NRF presents the key response principles, identifies the participants and their roles, and describes structures that guide the Nation's response operations. It provides all response personnel, including you, with guidance and information relating to:

slide 15

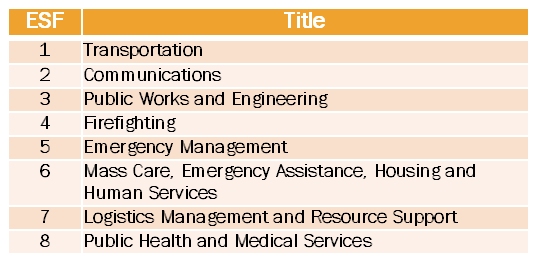

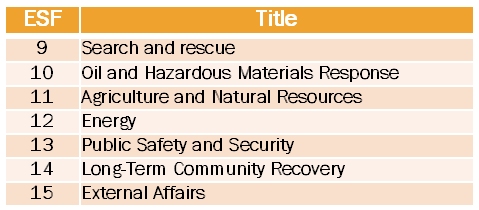

What are the 15 Emergency Support Functions identified in the NRF?

Slide Notes:

The Federal Government and many State governments organize much of their resources and capabilities – as well as those of certain private-sector and non-governmental organizations – under 15 Emergency Support Functions (ESFs). ESFs align categories of resources and provide strategic objectives for their use. ESFs utilize standardized resource management concepts such as typing, inventorying, and tracking to facilitate the dispatch, deployment, and recovery of resources before, during, and after an incident. ESF coordinators and primary agencies are identified on the basis of authorities and resources. Support agencies are assigned based on the availability of resources in a given functional area. ESFs provide the greatest possible access to Federal department and agency resources regardless of which organization has those resources.

During a Federal response, the ESFs are coordinated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) through its National Response Coordination Center (NRCC), Regional Response Coordination Center (RRCC), or Joint Field Office (JFO). During a Federal response, ESFs are a critical mechanism to coordinate functional capabilities and resources provided by Federal departments and agencies, along with certain private-sector and non-governmental organizations. They represent an effective way to bundle and funnel resources and capabilities to local, tribal, State, and other responders. These functions are coordinated by a single agency but may rely on several agencies that provide resources for each functional area. The mission of the ESFs is to provide the greatest possible access to capabilities of the Federal Government regardless of which agency has those capabilities.

The ESFs serve as the primary operational-level mechanism to provide Federal assistance in functional areas such as transportation, communications, public works and engineering, firefighting, mass care, housing, human services, public health and medical services, search and rescue, agriculture and natural resources, and energy.

slide 16

Slide Notes:

The first eight Emergency Support Functions and Primary Federal Agencies for the Federal government are:slide 17

Slide Notes:

The remaining Emergency Support Functions and Primary Federal Agencies for the Federal government are:

The same ESFs will be identified in most State Emergency Operations Plans (EOP). While the concept of ESFs has been around for a long time, it was primarily a purview of the Federal government. However, with the publishing of the National Response Plan, which was superseded by the NRF, States have begun organizing along the same framework. Some States have identified additional ESFs for their EOPs, so you may hear about ESFs 16, 17 or higher. Some States do not call them by the ESF number; instead, they use the name of the ESF such as Transportation, Communications, or Public Safety. Your state might use some other form of organizing capabilities for response activities.

slide 18

Slide Notes:

The U.S. Department of Transportation is the Lead Federal Agency for ESF 1, Transportation. In the same manner, the State DOT usually has the leadership role within the state for all matters relating to transportation: infrastructure, including roads, tunnels and bridges; transit systems; airfields; canals; and railroads; as well as for all preparedness activities, response operations, and recovery and mitigation activities related to transportation resources. The ESF lead agency coordinates planning efforts and the use of resources from other State agencies that may be identified to provide support. In the same manner, your State DOT may support some of the other ESF lead agencies.

The following Federal Departments support U.S. DOT in performing ESF 1, Transportation responsibilities:

In the same manner, your State DOT will probably be supported by other State agencies, according to your State's Emergency Operations Plan.

The Federal Emergency Support Function 1, Transportation, is NOT the primary agency responsible for the movement of goods, equipment, animals or people. However, you have to keep in mind that each state is organized differently, so in some cases your State DOT may be involved in these transportation activities to some degree.

slide 19

Slide Notes:

According to the NRF, the U.S. DOT is responsible for:

slide 20

Slide Notes:

As the State ESF 1, Transportation, primary agency, your DOT might do these types of activities:

slide 21

Slide Notes:

It is very important to understand three (3) major principles in the NRF:

slide 22

Slide Notes:

The National Incident Management System (NIMS) is a companion document to the National Response Framework (NRF). The NIMS provides a systematic, proactive approach to guide departments and agencies at all levels of government, non-governmental organizations (NGO), and the private sector to work seamlessly to prevent, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of incidents, regardless of cause, size, location, or complexity, in order to reduce the loss of life and property and harm to the environment.

Together the National Incident Management System (NIMS) and the National Response Framework (NRF) have a common goal – the efficient management of incidents and use of resources. NIMS provides the template for the management of incidents, while the NRF provides the structure and mechanisms for national-level policy for incident management.

The NIMS is intended to:

In other words, the NIMS is intended make sure all organizations are on the same page when responding to all types of emergencies.

The NIMS provides the template for the management of incidents, while the NRF provides the structure and mechanisms for the National policy for providing resources and managing the Federal response.

slide 23

Slide Notes:

Why is there a National Incident Management System?

Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD)-5, Management of Domestic Incidents, directed the development and administration of the National Incident Management System (NIMS). Originally issued on March 1, 2004, by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), NIMS provides a consistent nationwide template to enable Federal, State, tribal, and local governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector to work together to prevent, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of incidents, regardless of cause, size, location, or complexity.

NIMS was originally published in March 2004 and received its first true test during the response to and management of the Hurricane Katrina Disaster. Using lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina and other events, a revised NIMS was published in 2008.

slide 24

Slide Notes:

Intent

Consistent use of the NIMS lays the groundwork for response to all emergency situations, from a single agency responding to a fire, to many jurisdictions and organizations responding to a large natural disaster or act of terrorism.

An important effect of the NIMS is that it creates a common approach in both pre-event preparedness and post-event response activities that allow responders from many different organizations to effectively and efficiently work together at the scene of an incident.

Under the NIMS, responders from a wide variety of jurisdictions and agencies know what to expect and what to do when they arrive at an incident scene.

The NRF and NIMS are companion documents that were created to improve the Nation's incident management and response capabilities. Together, the NRF and NIMS provide for the effective integration of the capabilities and resources of various governmental jurisdictions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector incident management and emergency response disciplines into a cohesive, coordinated and seamless national framework for incident response.

slide 25

Slide Notes:

NIMS has five (5) components. Four (4) of these and what they mean to a State Department of Transportation (DOT) are:

The fifth component is Ongoing Management and Maintenance, which is simply the process of ensuring continued coordination and oversight of the program by an element of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

slide 26

Slide Notes:

The Incident Command System (ICS) is the NIMS element with which you should become most familiar. ICS provides a standardized, yet flexible, management process to ensure all resources committed to a response, whether the resources are provided from different organizations within or outside a single jurisdiction, or, for complex incidents with national implications, are used in the best way possible. When an incident requires response from multiple local response agencies, effective cross-jurisdictional coordination using common processes and systems is critical to an effective response and for the safety of the responders.

ICS allows responders from outside a local jurisdiction or state to volunteer or be sent to another incident scene and still understand the terminology and operations being used. You could be sent to an area other than the one you report to on a daily basis, especially during a regional or statewide incident or when those who would normally respond are affected by the situation and external resources need to be brought in to help.

State and Federal governments and departments/agencies also use principles of ICS. This is generally seen in the organizational structures that have common elements to facilitate coordination both vertically – from local to State to Federal – and horizontally – local to local, State to State and between Federal departments and agencies.slide 27

Slide Notes:

What is ICS?

The ICS has been tested and proved effective in more than 30 years of emergency and non-emergency applications, by all levels of government and the private sector.

The ICS is:

The ICS consists of procedures for managing personnel, facilities, equipment, and communications resources. It is a system designed to be used from the beginning to the end of an incident.

The ICS is designed to:

slide 28

Slide Notes:

The ICS was developed in the 1970s following a series of catastrophic fires in California's wildlands. What were the lessons learned? Surprisingly, studies found that response problems were far more likely to result from inadequate management than from lack of resources or tactics.

Weaknesses were often due to:

slide 29

Slide Notes:

Definition: An incident is an occurrence, regardless of cause, that requires response actions to prevent or minimize loss of life, or damage to property and/or the environment.

Examples of incidents include:

slide 30

Slide Notes:

Given the size of some of these types of events, it's not always possible for any one agency alone to handle management and resource needs.

The ICS is a standard, on-scene, all-hazard incident management approach. It allows responders to use the same organizational structure for a single or multiple incidents regardless of boundaries.

The ICS has considerable internal flexibility, that is, the management organization can grow or shrink to meet different requirements. This flexibility makes it a very cost effective and efficient management approach for both small and large situations.

slide 31

Slide Notes:

ICS Features

ICS principles are implemented through a wide range of management features including;

slide 32

Slide Notes:

ICS Features

The ICS emphasizes effective planning, including:

At the simplest level, all Incident Action Plans must have four (4) elements:

slide 33

Slide Notes:

ICS Features

ICS features related to command structure include:

ICS resources can be divided into two (2) categories:

ICS helps organizations ensure that resources are on hand and ready through:

NOTE: Resources are generally provided by the lowest level jurisdiction possible – local governments use their resources first, then States provide additional resources, followed by the Federal government when necessary.

slide 34

Slide Notes:

ICS Features

And, finally, ICS supports responders, and decision makers by providing the data needed through effective information management.

Communication equipment, procedures, and systems must be interoperable; that is, they must allow communication between organizations and across jurisdictions. For example, it is important that deployed State DOT personnel are able to communicate with local highway department or airfield personnel as well as the incident supervisor.

slide 35

Slide Notes:

In ICS:

Although orders must flow through the chain of command, members of the organization may directly communicate with each other to ask for or share information.

slide 36

Slide Notes:

The command function may be carried out in three(3) ways:

slide 37

Slide Notes:

Transfer of Command

The process of moving the responsibility for incident command from one Incident Commander to another is called transfer of command. Transfer of command may take place when:

The transfer of command process always includes a transfer of command briefing, which may be oral, written, or a combination of both. In the very early stage of an incident response, the first person of authority at the scene becomes the Incident Commander. When another person of authority arrives and will replace that initial Incident Commander, some of the things need to be included in the transfer of command briefing are:

slide 38

Slide Notes:

Accountability

Effective accountability during incident operations is essential at all jurisdictional levels and within individual functional areas. All State DOT personnel responding to the incident must abide by DOT policies and guidelines, and any applicable local, tribal, State, or Federal rules and regulations. Additionally, the following ICS guidelines must be adhered to:

slide 39

Organization for Incident Command

Slide Notes:

ICS organization is standardized and easy to understand. There is no correlation between the ICS organization used for incident response and the day-to-day administrative structure of any single agency or jurisdiction, with the possible exception of the military. This is deliberate, because confusion over different position titles and organizational structures has been a significant stumbling block to effective incident management in the past.

For example, you may be an Office Manager during day-to-day operations, but will likely not hold that title when working under the ICS structure.

slide 40

Slide Notes:

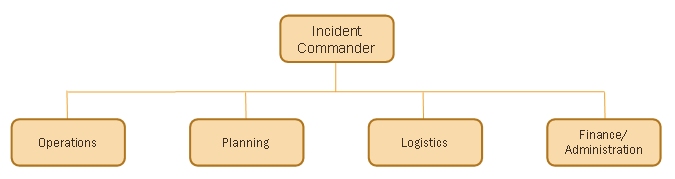

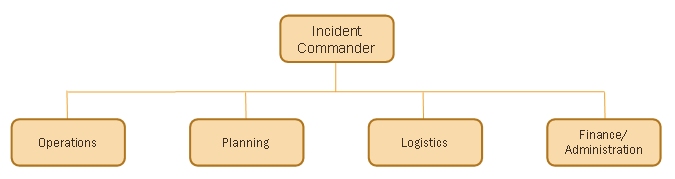

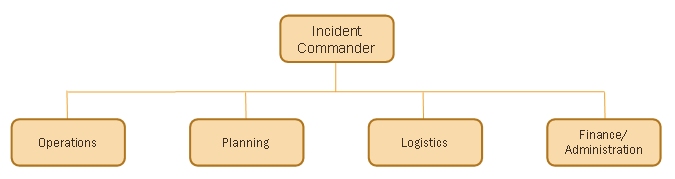

There are major management functions that are the foundation upon which the ICS organization develops. These functions apply whether the incident is a routine emergency, is organizing for a major non-emergency event, or when managing a response to a major disaster. The major management functions are:

You may hear these referred to C-FLOP. This is an easy way to remember the first letter of each of the functions: Command, Finance, Logistics, Operations, and Planning.

Organizational Structure: Incident Commander

On small incidents and events, one person, the Incident Commander, may accomplish all management functions. In fact, the Incident Commander is the only position that is always staffed in ICS applications. However, large incidents or events may require that some of these management functions be set up as separate Sections within the organization.

Organizational Structure: ICS Sections

Each of the primary ICS Sections may be subdivided as needed. The ICS organization has the capability to grow or shrink to meet the needs of the incident.

slide 41

| Organizational Level | Title | Support Position |

|---|---|---|

| Incident Command | Incident Commander | Deputy |

| Command Staff | Officer | Assistant |

| General Staff (Section) |

Chief | Deputy |

| Branch | Director | Deputy |

| Division/Group |

Supervisor | N/A |

| Unit | Leader | Manager |

| Strike Team/Task Force |

Leader | Single Resource Boss |

Slide Notes:

A basic ICS operating guideline is that the person at the top of the organization is responsible until the authority is delegated to another person. Thus, on smaller incidents when these additional persons are not required, the Incident Commander will personally accomplish or manage all aspects of the incident organization. ICS Position Titles To maintain span of control, the ICS organization can be divided into many levels of supervision. At each level, individuals with primary responsibility positions have distinct titles. Using specific ICS position titles serves three (3) important purposes: Titles provide a common standard for all users. For example, if one agency uses the title Branch Chief, another Branch Manager, etc., this lack of consistency can cause confusion at the incident. The use of distinct titles for ICS positions allows for filling ICS positions with the most qualified individuals rather than by seniority. Standardized position titles are useful when requesting qualified personnel. For example, in deploying personnel, it is important to know if the positions needed are Unit Leaders, clerks, etc.slide 42

Incident Commander Responsibilities

Slide Notes:

The Incident Commander has overall responsibility for managing the incident by objectives, planning strategies, and implementing tactics. The Incident Commander must be fully briefed and, if possible, have a written delegation of authority. Initially, assigning tactical resources and overseeing operations will be under the direct supervision of the Incident Commander.

Incident Commander Responsibilities

In addition to having overall responsibility for managing the entire incident, the Incident Commander is specifically responsible for:

The Incident Commander may appoint people to advise or perform these functions on his/her behalf. When this occurs, these individuals become the Command Staff.

The Incident Commander may appoint one (1) or more Deputies, if applicable, from the same agency or from other agencies or jurisdictions. Deputy Incident Commanders must be as qualified as the Incident Commander because the Deputy has to be able to take the Commander's place if the Commander is unable to continue in the position.

Formal transfer of command at an incident always requires a transfer of command briefing for the incoming Incident Commander and notification to all personnel that a change in command is taking place.

slide 43

Slide Notes:

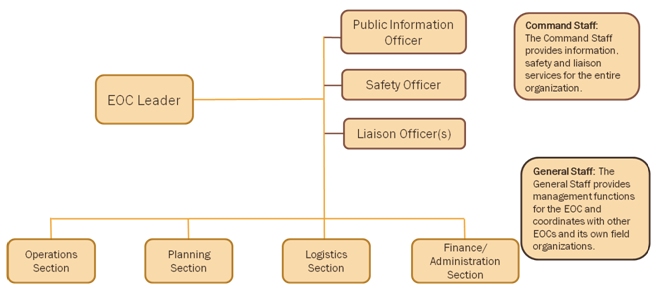

Command Staff

Depending upon the size and type of incident or event, it may be necessary for the Incident Commander to designate personnel to provide information, safety, and liaison services for the entire organization. In ICS, these personnel make up the Command Staff and consist of the:

The Command Staff reports directly to the Incident Commander.

slide 44

Slide Notes:

Expanding the Organization

As incidents grow, the Incident Commander may delegate authority for performance of certain activities to the Command Staff and the General Staff. The Incident Commander will add positions only as needed.

Expansion of the incident may also require the delegation of authority for other management functions. The people who perform the other four (4) management functions are designated as the General Staff. The General Staff is made up of four (4) Sections, representing the four (4) functional areas:

The General Staff reports directly to the Incident Commander.

slide 45

Slide Notes:

ICS Section Chiefs and Deputies

As mentioned previously, the person in charge of each Section is designated as a Chief. Section Chiefs have the ability to expand their Section to meet the needs of the situation. Each of the Section Chiefs may have one (1) or more Deputies, if necessary. The Deputy:

In large incidents, especially where multiple disciplines or jurisdictions are involved, the use of Deputies from other organizations can greatly increase interagency coordination. The Deputy:

slide 46

Operations Section

Slide Notes:

Operations Section

Until Operations is established as a separate Section, the Incident Commander has direct control of tactical resources. The Incident Commander will determine the need for a separate Operations Section. When the Incident Commander activates an Operations Section, he or she will assign an individual as the Operations Section Chief.

The Operations Section is not shown here with branches, groups or divisions or other sub-elements; the Operations Section is tailored for a specific response operation.

Operations Section Chief

The Operations Section Chief will develop and manage the Operations Section to accomplish the incident objectives set by the Incident Commander. The Operations Section Chief is normally the person with the greatest technical and tactical expertise in dealing with a specific incident type.

slide 47

Slide Notes:

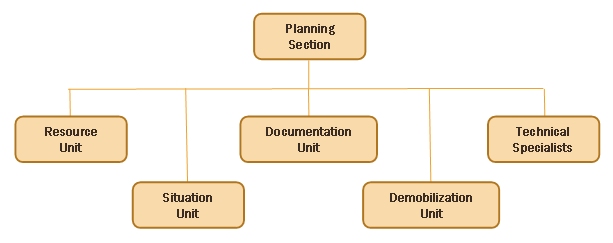

Planning Section

The Incident Commander will determine if there is a need for a Planning Section and designate a Planning Section Chief. If no Planning Section is established, the Incident Commander will perform all planning functions. It is up to the Planning Section Chief to activate any needed additional staffing.

The major activities of the Planning Section may include:

The Planning Section can be further staffed with five (5) Units. Technical Specialists such as engineers, surveyors, and encroachment permit coordinators, may be assigned to work in the Planning Section. Depending on the needs, Technical Specialists may also be assigned to other Sections in the organization.

slide 48

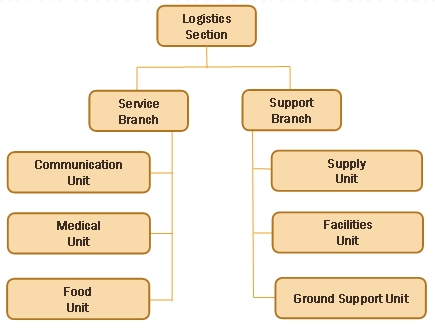

Slide Notes:

Logistics Section

The Incident Commander will determine if there is a need for a Logistics Section at the incident, and designate an individual to fill the position of the Logistics Section Chief. If no Logistics Section is established, the Incident Commander will perform all logistical functions. The size of the incident, complexity of support needs, and the incident length will determine whether a separate Logistics Section is established. Additional staffing is the responsibility of the Logistics Section Chief.

Logistics Section: Major Activities

The Logistics Section is responsible for all of the services and support needs, including:

The Logistics Section can be further staffed by two (2) Branches and six (6) Units. Not all of the Units may be required; they will be established based on need. The titles of the Units are descriptive of their responsibilities.

slide 49

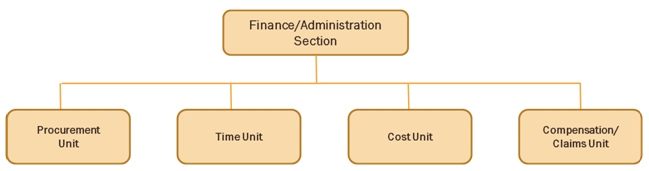

Slide Notes:

Finance/Administration Section: Major Activities

The Finance/Administration Section is set up for any incident that requires incident-specific financial management. The Finance/Administration Section is responsible for:

The Incident Commander will determine if there is a need for a Finance/Administration Section at the incident and designate an individual to fill the position of the Finance/Administration Section Chief. If no Finance/Administration Section is established, the Incident Commander will perform all finance functions.

The Finance/Administration Section may staff four (4) Units. Not all Units may be required; they will be established based on need.

slide 50

Slide Notes:

NOTE: The structure depicted is based on ICS, is NIMS-compliant, and is intended to be representative of many State EOCs. Your State EOC may be organized differently.

Your State will have an EOC that is managed by the State Emergency Management Agency. The purpose is to coordinate for and deploy State resources to support local governments. The EOC will also coordinate with other States and with the Federal government for resources.

Federal departments and agencies establish EOCs to manage its resources that are deployed to support incident response operations. The U.S. DOT not only provides ESF 1, Transportation personnel to the NRCC, the RRCC and the JFO, it manages all aspects of ESF 1, Transportation responsibilities as delineated by the NRF. These Federal ESF 1, Transportation representatives may seek to coordinate directly with your DOT representatives in the State EOC, and maybe directly with your DOT EOC.

Federal resources are deployed to the vicinity of the incident and managed tactically by the Joint Field Office (JFO). The JFO is organized like an EOC, but instead of an EOC Leader, it has a Unified Coordination Group representing the Federal and State, and sometimes local, agencies that work together to ensure the right resources get to the right place.

slide 51

Slide Notes:

Now that you have been exposed to the concepts, how does this all play out?

As mentioned previously, all incidents are managed locally. A city or county fire chief, police chief, or other local official will lead the community's response efforts as the Incident Commander. The Commander will establish a Command Post in the vicinity of the incident. A local government Emergency Operations Center (EOC) will be established to coordinate the provision of resources to the Incident Commander. In the local EOC, the highest elected official will normally be present, although most of the operations will be directed by the Operations Section Chief and/or the local Emergency Manager.

If the scope of the incident is large enough, the State will activate an EOC, bringing State agencies together to coordinate the mobilization and deployment of State resources to reinforce the capabilities of the local government. Most State EOCs have a direct representative of the Governor working directly with the EOC Team Leader.

slide 52

Slide Notes:

If the State indicates to the Federal government that they may need additional resources or the Federal government itself believes the State may need additional resources, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Regional Office will establish a Regional Response Coordination Center (RRCC) and the FEMA Headquarters establishes its National Response Coordination Center (NRCC). The FEMA Regional Administrator is the senior Federal official at the RRCC, and the FEMA Administrator is the senior official at the NRCC – both of which generally have a senior staff individual act as the Team Leader.

Coordination of Federal resources occurs forward of the RRCC at the Joint Field Office (JFO), generally located in the vicinity of either the State EOC or nearer to the incident, depending on the desires of the State. The JFO is led by a Unified Coordination Group – Federal Coordinating Officer, representing FEMA; the State Coordinating Officer, representing the Governor; and other senior Federal, State and/or local officials as appropriate for the type of incident. The JFO conducts operations in direct support of the State's efforts.

slide 53

Slide Notes:

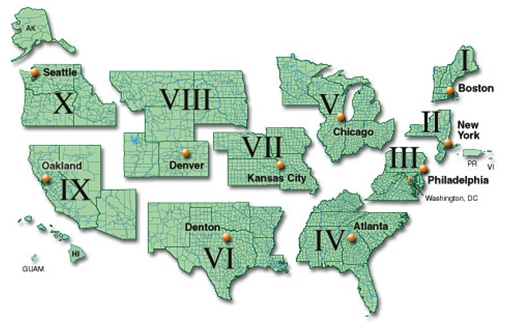

There are 10 FEMA Regions. Each FEMA Region provides direct support to the States in its Region:

The RRCC is established in the Regional Office or a nearby facility. Regional ESF and other regional Federal agency representatives arrive and begin to:

slide 54

Slide Notes:

Provision of Resources

Earlier in the discussion, we mentioned that resources should be obtained at the lowest level possible. There are two (2) more ways to obtain them:

Mutual Aid is a standing agreement between local governments and agencies to provide resources during an incident response. The best known of this type of assistance is when a fire department from a neighboring town assists a nearby department battling a large fire.

State resources are provided directly by the State to the local government – then the local government coordinates with the Incident Commander for tactical deployment.

EMAC is a formal agreement managed by the National Emergency Management Association (NEMA) that facilitates sharing resources between States. During the response to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, many States sent resources to Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas. The EMAC was the conduit through which these resources were coordinated.

Resources may also be provided by the Federal government following a Presidential Major Disaster Declaration or Emergency Declaration – see next slide.

slide 55

Slide Notes:

The Declaration Process

There is a formal process by which Federal resources are activated, mobilized and deployed to support incident response operations, as generally described below. However, these resources are usually not free – they are provided on a cost-share basis: 75 percent Federal, 25 percent State responsibility.

First Response to a disaster is the job of local government's emergency services with help from nearby municipalities, the State and volunteer agencies. In a catastrophic disaster, and if the Governor requests, Federal resources can be mobilized through the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for search and rescue, electrical power, food, water, shelter and other basic human needs.

It is the long-term Recovery phase of disaster that places the most severe financial strain on a local or State government. Damage to public facilities and infrastructure, often not insured, can overwhelm even a large city.

A Governor's request for a major disaster declaration could mean an infusion of Federal funds, but the Governor must also commit significant state funds and resources for recovery efforts.

slide 56

Slide Notes:

A Major Disaster could result from a hurricane, earthquake, flood, tornado or major fire which thePresident determines warrants supplemental federal aid. The event must be clearly more than state or local governments can handle alone. If declared, funding comes from the President's Disaster Relief Fund, which is managed by FEMA, and disaster aid programs of other participating federal agencies.

The Major Disaster Process

A Major Disaster Declaration usually follows these steps:

An Emergency Declaration follows much the same process.

slide 57

Slide Notes:

Disaster Aid Programs

There are three (3) major categories of disaster aid:

slide 58

Slide Notes:

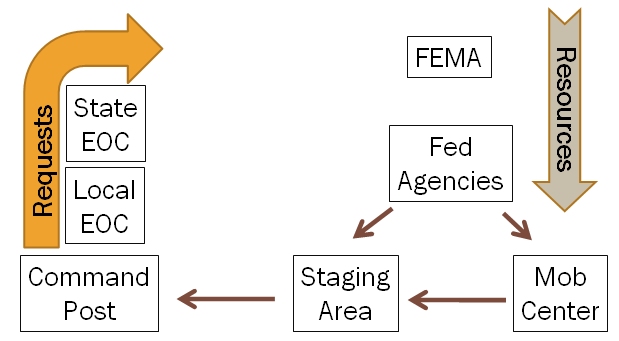

The Incident Commander requests additional resources through the Local EOC.

The request then goes to the State EOC and depending on the amount of time that has elapsed to either the RRCC or the JFO. Early in the response effort, the Operations Section in the RRCC will prepare a Mission Assignment and send that to a Federal agency.

Later in the response effort, the Operations Section in the JFO validates the request and coordinates with the RRCC and NRCC. If the JFO can fill the request, they send a Mission Assignment to the appropriate Federal Agency, working through the ESF representatives. If the JFO cannot fill the request, they coordinate with the NRCC to transmit the Mission Assignment, again working through the ESF representatives.

A Mission Assignment directs the Federal agency to provide the resource – and provides a fund code to reimburse the agency providing the resource.

The Federal agency deploys the resource to the Mobilization Center (Mob Center) if it is not immediately needed, or directly to the Staging Area for immediate use. The Incident Command Post then does the tactical employment of the resource. Some resources may be employed by the Local EOC, for example, support for care centers.

slide 59

Slide Notes:

In the previous slide, the discussion surrounded how Federal resources are requested and flow to an incident for use by the local government and responders.

In the area of Transportation, there should be ESF 1, Transportation personnel in each Operations Section:

However, the ESF representatives at all EOCs are constantly coordinating with other ESF representatives internally and with external ESF 1, Transportation representatives to identify:

slide 60

Slide Notes:

What is Recovery?

Following a fire in a person's house, the family rebuilds and tries to return to a normal life – this is recovery. Following an automobile accident, a person gets another car and carries on – this is recovery.

When used as an emergency management term, recovery is that time following an incident where governments undertake activities to restore infrastructure to a usable state. Buildings are rebuilt, just as houses are after a fire. Bridges, roads and other infrastructure will be repaired, relocated or rebuilt as conditions dictate.

When does it occur?

Recovery starts shortly after the initial life-saving response activities have occurred. Recovery begins with planning – identifying priorities and answering questions:

Recovery activities also comprise planning for continuation of essential services even though infrastructure has been destroyed, e.g., establishing temporary education facilities in modular buildings because a school was destroyed by a tornado.

Recovery can be a long-term activity depending on the amount of damage sustained, although restoration of public infrastructure is generally accomplished in a timely manner because of its importance to commerce.

slide 61

Slide Notes:

Now, we will look into what all this means to you.

slide 62

Slide Notes:

Now that you have learned about emergency management, you may be wondering what your role may be. You may have a direct or supporting role in your DOT's preparedness, response and recovery activities. An example of a direct role may be as a key individual in the DOT Emergency Operations Center (EOC), as an ESF 1, Transportation representative to the State EOC, or to the Joint Field Office (JFO). If you manage a field organization, you might be deployed, with your section, to the scene of an incident to support local incident management activities.

Your exact role will be based on several factors:

If you have a solid general knowledge of DOT roles/missions, you might be tapped for your management skills and assigned as the Section Chief or a Unit Leader in the Planning Section. In the same capacity, you could be assigned to represent ESF 1, Transportation at the State EOC. Likewise, even though your current position is "supervisor" or "manager," your position in support of an emergency response might be as a staff member with no supervisory or managerial role.

slide 63

Slide Notes:

The first step is to find out who the DOT Emergency Coordinator is and ask if you are being considered for an emergency assignment. If you find out you are going to be given an assignment, ask what will be expected of you; if you aren't being considered, you could volunteer – you might like the challenge.

So, you find out you are going to have an emergency assignment. How will you be expected to prepare for your assignment? There are several things you can do:

Ask if your DOT, or another organization, is sponsoring ICS courses and ask to attend them.

slide 64

Slide Notes:

You now have a role in emergency response. You find yourself contributing more and more time to activities outside your office: writing plans, taking training courses, participating in exercises.

And, you find that some of your staff members also being assigned to General Staff sections in the DOT EOC. This can often be the case in the Planning Section, as the other sections generally have some direct link to offices, such as: Human Resources, Finance, Contracting, Operations and Supply (Logistics). You will have to make sure they are given time to take courses and attend training and to participate in exercises. This has the potential to create temporary shortfalls in the coverage of essential functions.

There are times during a response that your office may be short personnel, as they go to the EOC or other emergency assignments. You will need to have a good understanding of the priorities of your day-to-day functions, so the personnel remaining can concentrate on completing the most important work. A good way to prepare for this is to ensure everyone is cross-trained on office functions.

In some offices, the functions may be aligned so closely to the EOC that emergency support becomes a first priority, e.g., the Contracting Office may have to switch priorities to execute contracts supporting emergency response operations.

Also, consider office succession planning. Who will be in charge if you are assigned to a position during an emergency?

slide 65

Slide Notes:

This briefing has provided you information about:

To learn more and conduct additional research, some references are provided on the next slide. If you have comments or questions, contact webmaster@dot.gov.

slide 66

Slide Notes:

These are on-line reference sources. You should also contact your DOT Emergency Coordinator who can give you DOT-specific information. When you start talking, your interest may well be interpreted as a desire to work more closely in the area of Emergency Management – go for it!