Victor H. Green - Author and Pioneer

Commemorating 2021 National African American History Month

by Nikisha M. Pickett

Author Victor H. Green in 1956.

Victor Hugo Green was born November 9, 1892 in Manhattan, New York City to William H. and Alice A. Green, but was eventually reared in Hackensack, New Jersey. He was the oldest of their three children.

In 1913, Green began his career as a postal carrier for the U.S. Postal Service in Bergen County, New Jersey. Five years later, he married Alma Duke of Richmond, Virginia. During the Great Migration, Alma moved from the South – like thousands of other Black Americans. Shortly after they married, the couple moved to Harlem in New York City, which was rapidly becoming the center of Black arts and culture – a period now known as “the Harlem Renaissance.”

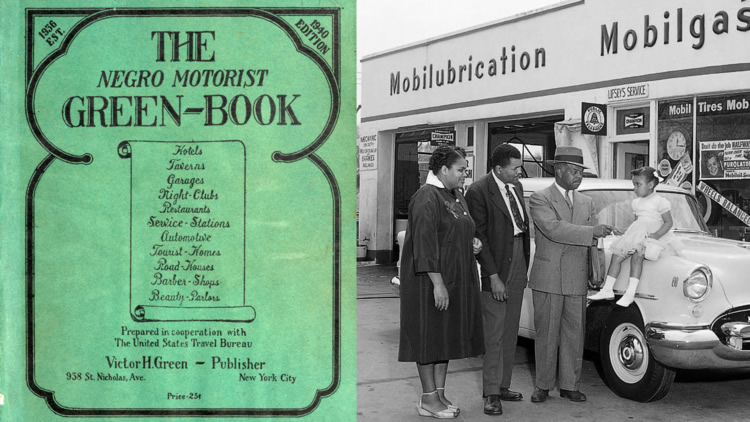

As African Americans began to increase their ownership of automobiles to travel for business and pleasure, they still were restricted by racial segregation. State laws in the South required separate facilities for African Americans and many motels and restaurants in northern states excluded them too. In an effort to help African Americans avoid humiliation and danger when traveling, Green created what was originally known as “The Negro Motorist Green Book.”

The Green Book was a guide published in 1936 that provided African Americans a list of safe places to eat, sleep and even fuel their cars as they navigated unfamiliar and potentially unsafe parts of the country during the Jim Crow era. The first edition of the Green Book, only 10 pages long, focused on hotels and restaurants in New York City as “Whites Only” policies meant that Black travelers often couldn’t find safe places to eat and sleep, and so-called “Sundown Towns”–municipalities that banned Black Americans after dark – were scattered across the country.

Due to the overwhelming response the Green Book received by many African Americans, later editions were expanded to include other cities in other states. Green was able to accomplish this by gathering field reports from fellow postal carriers as well as Green Book readers by offering cash payments to those that provided useful information. By the early 1940s, thousands of establishments nationwide – identified as either black-owned or verified to be non-discriminatory – were listed in the Green Book. For example, hungry motorists passing through Washington, D.C., were encouraged to stop for a bite at several places, including the Sugar Bowl on Georgia Avenue, or the Brass Rail near modern-day Howard University. Those looking for a bar in the Atlanta area were told to try the Sportsman’s Smoke Shop or Butler’s. In Richmond, Virginia, the Rest-a-Bit was the go-to spot for a ladies’ beauty parlor.

Introduction page from The Negro

Motorist Green Book: 1937.

Though most listings were in major cities such as Chicago, Illinois and Detroit, Michigan, more remote locations had fewer options. Alaska had only a single entry in the 1960 edition. In cities without Black-friendly hotels, the Green Book listed the addresses of home owners who were willing to rent rooms. Visitors to Roswell, New Mexico, in 1947 were encouraged to stay at the home of Mrs. Mary Collins.

Thanks to a sponsorship deal with Standard Oil, the Green Book was available for purchase at Esso (known today as ExxonMobil) gas stations across the country. Though largely unknown to Whites, the Green Book sold upwards of 15,000 copies per year. Thanks to its service to the motoring public’s safety, it is thought to be one of America’s earliest – and least appreciated – highway safety devices.

For more information about the Green Book, visit the following resources:

- The New York Public Library Digital Collections: The Green Book

- YouTube: The Green Book: Historic Travel Guide for Black America Part I

- YouTube: The Green Book: Historic Travel Guide for Black America Part II

- The Green Book: Guide to Freedom Documentary (preview)

- YouTube: The Importance of The Green Book with Brent Staples

- YouTube: “Green Book,” - 2018 Academy Award-nominated movie (preview)