A Moment in Time: A Moment in Time: Senator Al Gore Holds a Hearing

By Richard Weingroff

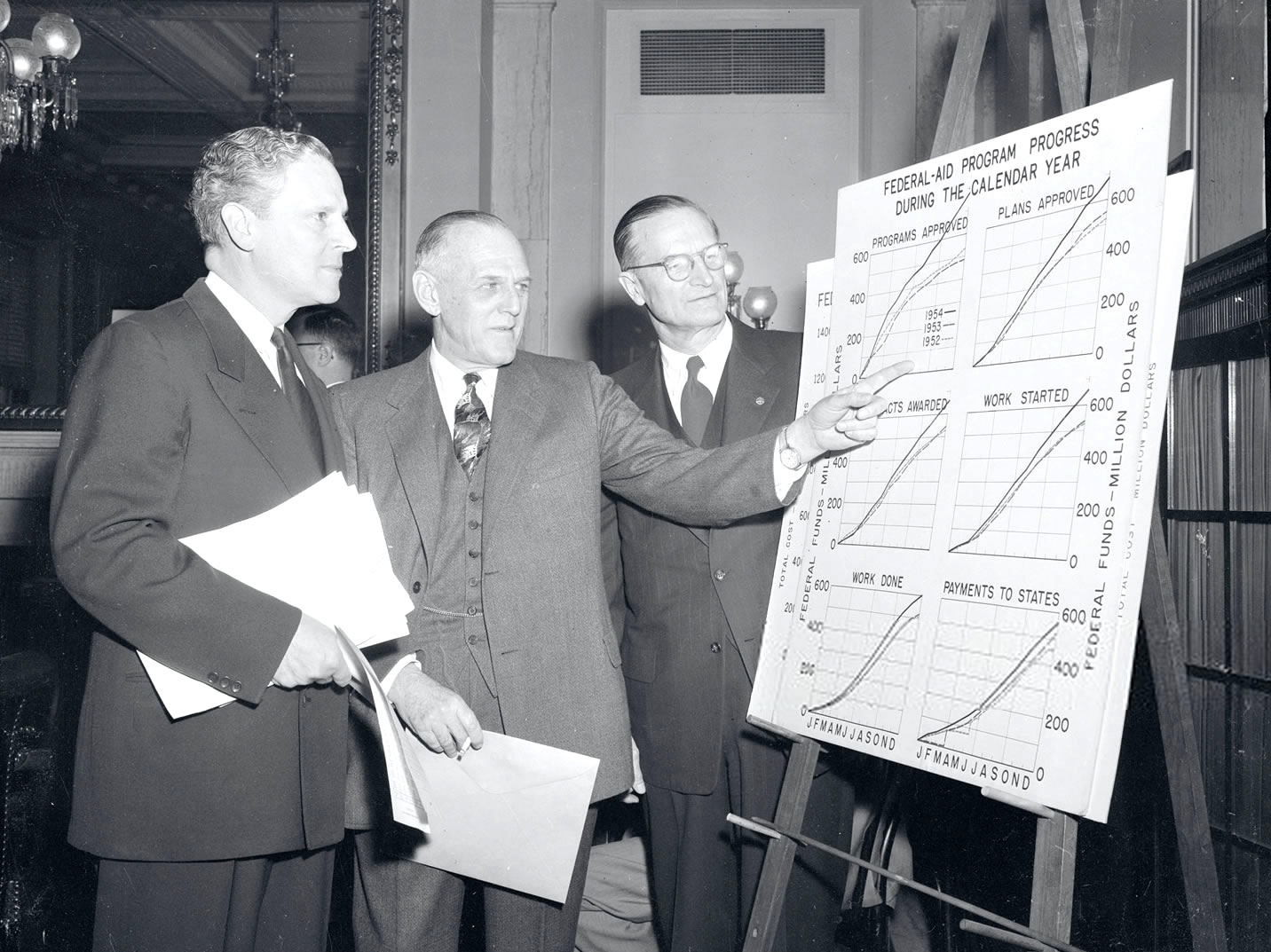

Former Commissioner of Public Roads Francis V. du Pont (center) described the progress of the Federal-aid highway program to Senator Albert Gore (left), chairman of the Subcommittee on Roads. Du Pont had resigned as Commissioner to devote his time to promoting President Eisenhower’s highway program. The new Commissioner of Public Roads, career BPR employee Charles D. “Cap” Curtiss, looks on.

Photograph Source: Getty Images / Bettmann.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower is often called the Father of the Interstate System, which since 1990 has been named after him: the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. He made the program a high priority, worked behind the scenes and in public to promote it, followed its progress during his second term in the White House, and after leaving office, told interviewers and historians it was one of his favorite programs.

At a moment in time, on February 21, 1955, the future of the President’s Grand Plan seemed to be in doubt.

The Plan

In 1954, President Eisenhower asked a colleague and friend, General Lucius D. Clay (retired), to head a committee that would work with the Nation’s Governors to develop a plan for improving the country’s roads, including roads owned by the Federal Government, the States, and local officials. Calculating the cost of the planned 40,000-mile Interstate network at $27 billion, the Clay Committee and the Governors agreed on a 10-year construction program, with the 90-percent Federal share to be financed by a new Federal Highway Corporation that would issue bonds for the full Federal share up front. The Federal gas tax, set at varying levels since 1932 but unrelated directly to the Federal-aid highway program, would be dedicated to retiring the bonds over 30 years. The new corporation would be off-budget so the expenditures would not add to the national debt, a primary concern of the President.

When General Clay began discussing the plan publicly in December 1954, the idea of an Interstate System was popular, but the funding mechanism proved controversial. Even the President was concerned about it. In a meeting with the Clay Committee on January 11, 1955, he expressed "tremendous enthusiasm" for the construction program, but asked why the committee had recommended gas taxes to repay the bonds instead of tolls, which the President favored. When General Clay replied that tolls would work only in the heavily populated areas where traffic volumes would support retirement of the bonds, Eisenhower accepted the explanation.

Critics in Congress and among highway boosters were harder to convince. For example, Senator Harry Flood Byrd (D-VA), the chairman of the Finance Committee, had what biographers have said was a nearly pathological opposition to debt. He called the debt-based financing concept “thoroughly unsound” and its exclusion from the budget an attempt “to defy budgetary control and evade federal debt law.” Senator Albert Gore (D-TN, father of the future Vice President of the same name), Chairman of the Subcommittee on Roads, said, “It’s a screwy plan which could lead the country into inflationary ruin.” Highway officials feared that the Federal Highway Corporation would have a veto over the Commissioner of Public Roads, head of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads (BPR).

The White House took longer than expected to work out the details and submit the plan to Congress. Finally, on February 1, White House officials agreed on the plan, drafted the President’s letter transmitting the report to Congress, and began mapping a strategy for selling it.

The Plan Takes Shape

As part of that strategy, the President invited General Clay to the White House on February 16, 1955, to brief senior Republican Members of Congress. Although Clay conducted the briefing, the President fed him questions to direct the dialogue. In addition, the President stressed what he considered to be the important points: "With our roads inadequate to handle an expanding industry, the result will be inflation and a disrupted economy."

While waiting for the White House to release the President’s plan, Gore introduced an alternative plan on February 11. His Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1955 proposed to continue the existing Federal-aid highway program while setting aside $500 million for the Interstate System annually through Fiscal Year 1960. Because the Constitution specified that revenue legislation must originate in the House, the Gore Bill was silent on how the revenue would be raised.

Chairman Gore scheduled a hearing for the morning of February 21 on the Administration plan and the Gore Bill. That same day, House and Senate Public Works leaders were to meet with the President in the afternoon.

The Busy Day

When the hearing began, Chairman Gore explained, “At the time I announced the hearing I fully expected that the administration proposal would be before the committee.” Based on that assumption, he had invited Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks to be the first witness (BPR was in his department), but the Secretary had to declined because of a prior commitment. In his place, Francis V. du Pont, would be the first witness. A wealthy former highway official from Delaware, du Pont had been Commissioner of Public Roads in 1953 and 1954 before resigning to take on a consultant role to help promote the President’s Interstate program.

Du Pont’s brief formal statement recounted developments leading to the Clay Committee, but indicated that “it would be premature for me to comment at this time, on any specific legislative proposals.” Although the Senators tried to get his comments on details already known about the Clay Committee’s plan or about the Gore Bill, du Pont declined each opportunity to respond directly. The frustrating dialogue ended abruptly:

Senator Gore. You do not think it is proper for this committee to take cognizance of the Clay report until it has been approved or not approved by higher authorities?

Mr. du Pont. I think it is entirely proper to discuss any of the factual data. I do not think it is proper to discuss the policies that may be included in the legislation that may be presented.

Senator Gore. Thank you, Mr. du Pont.

Reporters observing the exchange agreed that, as The New York Times put it, “Mr. Gore curtly dismissed him from the stand.”

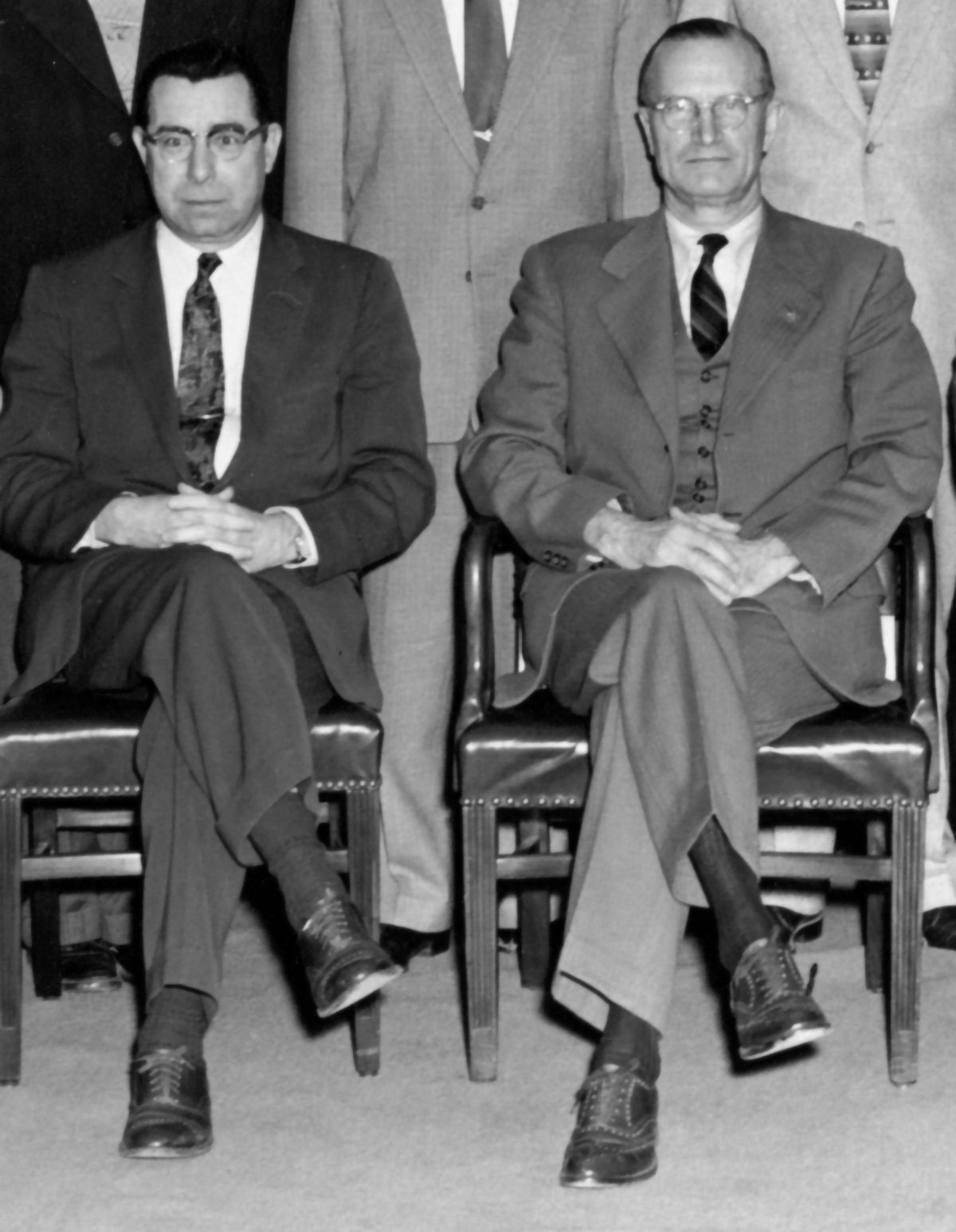

Charles D. “Cap” Curtiss, Commissioner of Public Roads (right), with Assistant to the Commissioner Francis C. "Frank" Turner in 1956.

The new Commissioner of Public Roads, Charles D. “Cap” Curtiss, a career BPR employee, was the only other witness that morning. He also was unable to comment directly on the Clay Committee report, the President’s bill, or the Gore bill. The hearing ended with everyone frustrated.

That afternoon, Senator Gore joined other Democratic chairmen and ranking Republican members of the House and Senate Public Works Committees at the White House for a meeting with the President and General Clay. It was the first time Democrats had been invited to the White House during the Eisenhower Administration to discuss domestic matters.

President Eisenhower told his guests that as Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe, he had been impressed by the efficiency of Germany’s autobahn, a network of rural superhighways, during and after the war. Returning to the United States, he had the “unpleasant experience” of traveling “on some of our roads” that compared poorly with the German network.

He stressed that with 60 million vehicles soon jamming the Nation's roads, "we will have to build up our highways to meet that traffic.” He wanted a sound highway plan that could “stand on its own feet,” based on the concept that highway users would provide the funds for its construction. Clay's 10-year plan for the Interstate System was "vitally essential for national defense," would “help the steel and auto spare parts industry,” and was, in short, "good for America." The issue, he said, was not partisan.

The visitors raised concerns. Senator Gore said “there are certain appealing features in the Clay program,” but criticized spending $11 billion for interest on the bonds. He argued, simply, "That money should be spent on roads." He also questioned the President on how the Administration could spend the money as proposed and still maintain that it would not increase the national debt. The President, according to Gore, smiled, then agreed it would be a debt, but it would not be part of the national debt.

Senator Dennis Chavez (D-NM), chairman of the Committee on Public Works, also expressed reservations to reporters. Before the meeting, he had said the Clay plan was “so full of holes it would sink,” and came out feeling “the same way.” The committee’s recommendations were “subject to serious doubts as to whether they could be effective.”

The Report

President Eisenhower forwarded the Clay Committee's 64-page report, A 10-Year National Highway Program, to Congress the next day, February 22. His transmittal letter began with a passage that often has been quoted as a summary of the President's views and a timeless statement about the role of highways specifically and transportation generally in the Nation’s life:

Our unity as a nation is sustained by free communication of thought and by easy transportation of people and goods. The ceaseless flow of information throughout the Republic is matched by individual and commercial movement over a vast system of interconnected highways crisscrossing the country and joining at our national borders with friendly neighbors to the north and south.

Together, the united forces of our communication and transportation systems are dynamic elements in the very name we bear – United States. Without them, we would be a mere alliance of many separate parts.

The need for action was inescapable. He cited safety (more than 36,000 killed), the poor condition of the roads, the need to evacuate cities in the event of an atomic attack, and the growth in traffic as the population and the gross national product increases ("existing traffic jams,” he said, “only faintly foreshadow those of 10 years hence").

The Clay Committee estimated that total highway needs equaled $101 billion:

Of all these, the interstate system must be given top priority in construction planning. But at the current rate of development, the interstate network would not reach even a reasonable level of extent and efficiency in half a century.

The Clay Committee recommended that the Federal Government assume principal financial responsibility for the Interstate System at 90 percent, at an annual cost of $2.5 billion for 10 years (10-year total Federal share: $25 billion), with the program to be completed by 1964,.

The President stated that a "sound Federal highway program, I believe, can and should stand on its own feet, with highway users providing the total dollars necessary for improvement and new construction." Therefore, he said:

I am inclined to the view that it is sounder to finance this program by special bond issues, to be paid off by the above-mentioned revenues which will be collected during the useful life of the roads and pledged to this purpose, rather than by an increase in general revenue obligations.

The Clay Committee’s report strongly endorsed the President's Grand Plan.

We are indeed a nation on wheels and we cannot permit these wheels to slow down . . . . We have been able to disperse our factories, our stores, our people; in short, to create a revolution in living habits. Our cities have spread into suburbs, dependent on the automobile for their existence. The automobile has restored a way of life in which the individual may live in a friendly neighborhood, it has brought city and country closer together, it has made us one country and a united people.

But, America continues to grow. Our highway plant must similarly grow if we are to maintain and increase our standard of living.

Reaction to the President’s plan was mixed. Further, the President’s phrase, “inclined to the view,” would quickly suggest to critics that he was not committed to the financial aspects of the proposal – the linchpin of the Clay Committee program. Journalist Theodore White wrote that the Clay Committee’s proposals were born “out of the amateur ruminations of a number of civic-minded gentlemen enthusiastically exploring our needs over a period of a few weeks.” What these gentlemen were about to find out was a simple truism about roads:

For the politics of American highways has always been dominated by one overwhelming truth: everyone loves roads, but no one wants to pay for them.

By March 3, Engineering News-Record could report that the Eisenhower highway program was “in trouble – bad trouble.” The financing mechanism, with its $11 billion in interest payments, was the chief problem. Critics considered the Administration bill a “bankers bill” that would provide too much benefit to bankers and investors who bought the bonds at the public’s expense.

The Results

Despite President Eisenhower’s strong support for the program, the Clay Committee’s financing plan undermined the proposed Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1955. The Gore Bill, minus the financing mechanism, passed the Senate by voice vote on May 24. Before doing so, the Senate rejected, 31 to 60, a motion to substitute the Administration bill for the Gore plan.

Bad as that was, House rejection was even more pointed. On July 27, 1955, by a vote of 193 to 221, the House defeated a motion to recommit (i.e., send back to committee) a bill developed by Representative George H. Fallon (D-MD), Chairman of the Subcommittee on Roads, and substitute the Administration’s bill. The Fallon Bill proposed to finance the Interstate program on a pay-as-you-go basis with increases in highway user taxes dedicated to that purpose. Then, in one of the biggest surprises of the session, the House rejected the Fallon Bill, 123 to 292. The defeat was even more astonishing because debate during the day had been objective and sincere, with the Fallon Bill surviving the vote to substitute the Eisenhower plan.

In the wake of what Transport Topics called this "astonishing, entirely-unexpected defeat," Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn (D-TX) said the vote had killed chances for highway legislation in 1955 "and probably next year too, with the House as divided as that." He blamed the defeat on lobbyists. "The people who were going to have to pay for these roads put on a propaganda campaign that killed the bill," he said.

The next day, July 28, President Eisenhower issued a statement saying he was “deeply disappointed” by the House action. “The nation badly needs new highways. The good of our people, of our economy and of our defense, required that construction of these highways be undertaken at once.” He added that “contention over the method should not be permitted to deny our people these critically needed roads.”

He hoped Congress would reconsider the matter before adjourning, but Speaker Rayburn declared, "No chance – none whatever." Congress adjourned for the year on August 2.

Eisenhower, in a memoir, explained that he discounted a proposal by his staff to call a special session of Congress to consider the highway plan:

"Well," I said, somewhat ruefully, "the special session might be necessary – but calling it could be at the cost of the sanity of one man named Eisenhower."

Success at Last

Before Congress returned in January 1956, White House officials, Members of Congress, highway officials, and the highway interests reached an agreement on highway user taxes that had eluded them in 1955. With the addition of the Highway Trust Fund concept, suggested by Secretary of the Treasury George M. Humphrey with the Social Security Trust Fund as a model, the legislation moved quickly through Congress.

On June 29, when President Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, he launched what people at the time – and since – referred to as the greatest public works project in history.

The moment in time on February 21, 1955 – when a hearing came to an abrupt end and Members of Congress, Democrats as well as Republicans, raised concerns directly to President Eisenhower at the White House – signaled problems ahead for his Grand Plan. The problems raised about financing did delay approval of the plan for over a year, but in the end, it turned out to be a setback, one of many, before ultimate success on June 29, 1956. In a memoir, Eisenhower wrote:

More than any single action by the government since the end of the war, this one would change the face of America . . . . Its impact on the American economy – the jobs it would produce in manufacturing and construction, the rural areas it would open up – was beyond calculation.