Moment in Time: How the Washington Monument Helped Solve a Bridge Impasse

By Richard F. Weingroff

To decide whether the new bridge should include two four-lane spans or one six-lane span across the Potomac River, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickles (left) invited President Harry S. Truman (gesturing at window) to the top of the Washington Monument on January 14, 1946. With them are Associate Director Arthur E. Demaray of the National Park Service and General Ulysses S. Grant III, chairman of NCP&PC the National Capital Park and Planning Commission, all single-bridge advocates. (Harry S. Truman Library)

We tend to forget that many of our most admired sites were highly controversial before they were built. The list of great works that emerged from controversy is long – the Eiffel Tower, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Golden Gate Bridge, the Hoover Dam, the Lincoln Memorial, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the World War II Memorial, and the transcontinental railroad – treasures so obvious today that we don't recall the predictions of doom before they were built.

And then there were the battles over construction of urban freeways. During the Interstate System's active construction years after 1956, the Washington area was a national leader in long-running battles over urban Interstates. However, Washington controversies about roads and bridges predated the Interstate era. For example, there was the debate over replacing the Highway Bridge at the site of today's I-395/14th Street Bridge complex across the Potomac River between the District and Virginia. The location had a long bridge history.

First came the Long Bridge that President Thomas Jefferson authorized on February 8, 1808. The $100,000 toll bridge opened in May 1809, with a broad carriageway and pedestrian paths on both sides. President James Madison was the first to cross the Potomac River on the bridge in his carriage to Alexandria (then part of the capital city). Floodwaters damaged that bridge 20 years later, but the toll company could not afford the repairs. Congress financed a new bridge that President Andrew Jackson and his Cabinet celebrated by walking across to Alexandria when the new $130,000 Long Bridge opened in October 1835. They returned in carriages.

By the 20th century, the Pennsylvania Railroad controlled the Long Bridge, which was primarily used by railroads and an interurban trolley line. It was replaced by a double-tracked railroad bridge that opened on August 25, 1904, while the old Long Bridge was replaced 2 years later by a bridge that cost $1,196,000 and, in a reflection of the changing times, was known as the Highway Bridge.

In the 1940s, officials began planning to replace the Highway Bridge, which carried traffic across the river on Maine-to-Florida U.S. 1. They saw the replacement as a vital post-World War II project, but were split on what was needed. District officials favored replacing it with twin spans of four lanes each. The Public Roads Administration (PRA, as FHWA was known in those days) supported the District's view.

The National Capital Park and Planning Commission (NCP&PC) and the National Park Service (NPS) supported a single-span option with six lanes. They argued that much of the traffic on U.S. 1 would bypass the city if a bridge was built as proposed across the Potomac River at Alexandria. With through traffic diverted, a single six-lane bridge could handle the remaining traffic in the 14th Street corridor. (The Alexandria bypass idea would result in Congress authorizing funds for the Bureau of Public Roads (another of our early names) to build the first Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge, which opened on December 28, 1961, as part of the Capital Beltway.)

Commissioner Thomas H. MacDonald of PRA replied to the idea of diverting traffic to an Alexandria bypass bridge by saying, "it is my considered judgment that it would be unwise to construct a facility of inadequate capacity with the hope that such an act would cause the building of an additional facility at another location, and that the two combined would solve the problem."

Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes (pronounced: ICK' ees) strongly agreed with his department's NPS. He argued that the two-bridge option would cost too much and "do violence" to the approach to the Nation's capital. In particular, the two bridges would overshadow the Jefferson Memorial that had opened on April 13, 1943. It also, he said, would overburden area streets with more traffic, working in contrast to a "sound economy and modern city planning."

Nevertheless, on July 21, 1944, the District commissioners (three presidentially appointed commissioners, one from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, governed the city during this period) approved the two-bridge plan on July 21, 1944. But as often is the case with such controversies, approval of the plan only unleashed even more strenuous arguments.

In 1945, with the end of the war in sight, the debate went from academic to serious because funds would soon be available for civilian construction projects. Representative Jennings Randolph (D-WV) introduced a bill authorizing $7 million for the two-bridge replacement. In December 1945, Representative Virgil M. Chapman (D-Ky.), chairman of the Subcommittee on Bridges of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, held a hearing on the Randolph Bill.

Secretary Ickes, appearing before the subcommittee on December 18, denounced the District's plan for two four-lane bridges. Citing the visual impact on the Jefferson Memorial of cars instead of trees, he said he could "only compare such a backdrop to the mechanical ducks which move across the back of every two-bit shooting gallery in the country." He predicted that the additional traffic from the eight lanes would require additional funds to depress or elevate roads throughout downtown Washington.

The debate continued, with authorities on both sides disputing traffic projections, cost estimates, aesthetic criteria, and each other's credibility. Then, in a reflection of the debate's importance, Secretary Ickes dragged President Harry S. Truman into the dispute.

Elevating the Bridge Battle

Secretary Ickes arranged for President Truman to join a group of single-bridge supporters on January 14, 1946, at the top of the Washington Monument for a bird's eye view of the site. In so doing, President Truman became the first Chief Executive to travel to the top of the monument.

In addition to Secretary Ickes, the party included NPS Associate Director Arthur E. Demaray and General Ulysses S. Grant III, chairman of NCP&PC. During their half hour atop the monument, The Evening Star reported, they discussed the bridge proposal as well as other aspects of the area's post-war public building program.

After leaving the Washington Monument, the group drove across the Highway Bridge into Virginia. They returned via Arlington Memorial Bridge. According to the Star, "It was reliably understood today that the President did not commit himself on the bridge proposal, allowing these three officials to do most of the talking," referring to Secretary Ickes, Associate Director Demaray, and General Grant.

On June 6, with the Randolph Bill still in committee, the White House released President Truman's decision. Matthew J. Connelly, Secretary to the President, wrote to District Commissioner John Russell Young:

The President has directed that I advise you that he favors the two-bridge plan for replacement of the present Highway Bridge across the Potomac River. He has also directed that a copy of this letter be sent to the National Park and Planning Commission and the Bureau of Public Roads [using the 1920s-1930s name for PRA].

The brief letter did not explain the decision, but the Star's editors hoped that he was agreeing with those "who have taken the view that within a few years one bridge would be incapable of handling the growing volume of traffic and that long-range economy and sound traffic engineering make two one-way structures advisable." The editors hoped "the President's candid indorsement of the plan . . . will produce some action from the subcommittee" on the Randolph Bill. That it did – although even a clear, uncomplicated, and impossible-to-misinterpret presidential decision does not necessarily mean an end to a dispute.

On June 14, members of the Chapman subcommittee followed President Truman's example by ascending the Washington Monument to survey the area. Chairman Chapman and two other committee members were accompanied by General Grant, Demaray, Deputy Commissioner for Design H. E. Hilts of PRA, and Captain Herbert C. Whitehurst, District Director of Highways. The accompanying officials were split among one-bridge and two-bridge men (in contrast to the one-bridge officials accompanying the President on January 14).

The officials were at the top of the monument for almost an hour, with each side citing familiar arguments. In addition, Demaray and General Grant questioned whether the economy-minded Congress would go along with the higher cost for the two-bridge solution; perhaps Congress would approve the two spans, but not appropriate funds for the second span until some unknown future date.

Captain Whitehurst and Hilts pointed out that PRA and the District would split funding for the bridges on a standard 50-50 basis under the Federal-aid Highway Program. Funding, therefore, would not be a problem. (Although PRA could guarantee the Federal-aid 50 percent, the District's 50-percent matching share in the pre-home rule days was subject to congressional authorization and appropriation acts.) They predicted construction would take only 3 years, in part because building twin bridges meant they would save time by using the same forms and specifications for both spans. The northbound span, they said, would be about 600 yards from the Highway Bridge, providing a fine view of the Jefferson Memorial for traffic crossing from Virginia.

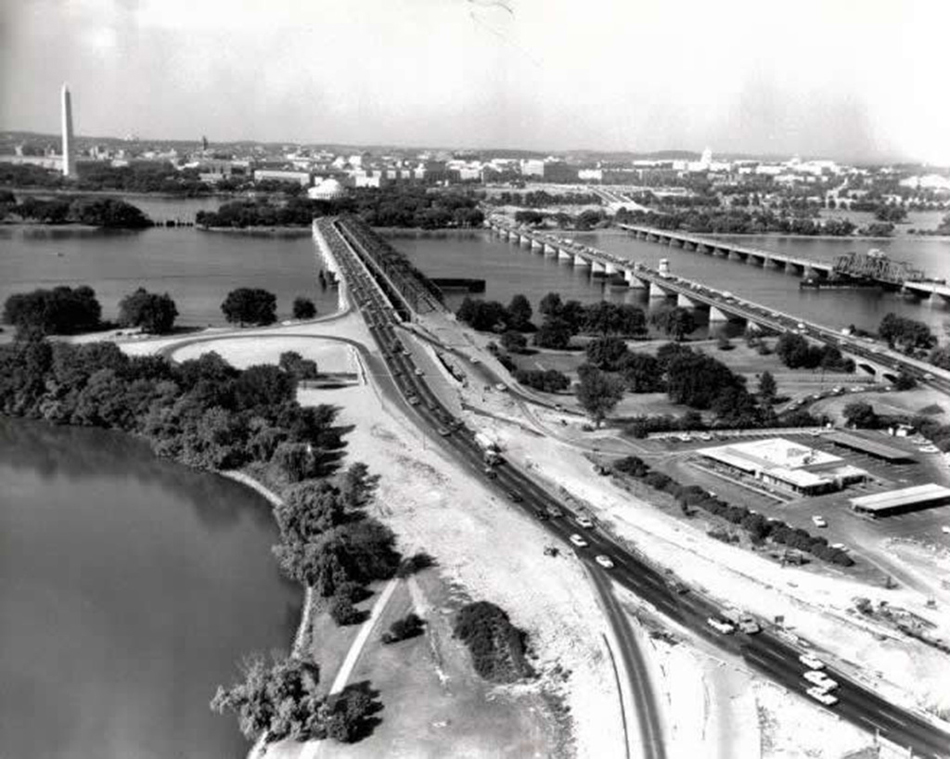

This photograph shows the Potomac River crossings in 1962. From left to right, the crossings are the George Mason Memorial Bridge (1962), the Highway Bridge (1906), the Rochambeau Memorial/Arland D. Williams Jr. Bridge (1950), and the Potomac Railroad Bridge (1904). (FHWA)

Captain Whitehurst added that the Highway Bridge was in such poor condition that it could not serve as a substitute for one of the twin spans, as suggested by single-span supporters. The Star summarized Whitehurst's argument: "Its piers are subject to scour, its bed is laminated wood already rotten in spots, and the draw machinery is 'about shot.'"

On June 26, the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce approved the two-span Randolph Bill. The House approved the bill unanimously on July 3, with limited debate. The Senate approved an identical bill on July 7 by unanimous consent. President Truman signed the legislation on July 17, 1946. Four years later, on May 9, 1950, officials dedicated the first span of the new 14th Street Bridge. Miss Mary Jane Hayes, Miss Washington of 1949, snipped the red ribbon before a crowd of about 300 people. After the ceremony, an official motorcade crossed the bridge into Virginia.

On October 19, 1958, an Act of Congress officially named the span the Rochambeau Memorial Bridge to honor the Comte de Rochambeau, of France. The Star explained, "Last year was the 175th anniversary of the time when Gen. Rochambeau crossed the Potomac near the site of the present bridge on the way to aid Gen. Washington's forces in the Battle of Yorktown," which essentially ended the Revolutionary War. During the bridge ceremony, "French Ambassador Herve Alphand declared the dedication bound more closely the historic ties of friendship between his country and the United States."

The new bridge carried four lanes of District-bound traffic while the aging Highway Bridge carried Virginia-bound traffic until the second span could be opened. Contrary to Captain Whitehurst's confident expectation, that would not be until January 27, 1962, when the four-lane George Mason Memorial Bridge opened and became the southbound roadway. District, Virginia, and Federal officials gathered for the ceremony, which included unveiling a plaque honoring Mason, a Virginia plantation owner and politician, friend of George Washington, and an influential participant in the Constitutional Convention who refused to sign the document because it lacked a Bill of Rights similar to one he had drafted for Virginia.

The Highway Bridge could finally be removed.

In 1983, Air Florida Flight 90 crashed while taking off from Washington National Airport in a snowstorm, damaging the Rochambeau Memorial Bridge. The bridge was renamed as a posthumous honor for Arland Williams, Jr., a heroic passenger who lost his life helping others escape the airplane. The original name was shifted to a bridge opened in 1972 to carry high occupancy vehicles.

Born in controversy, the twin spans of the Mason and Williams Bridges owe their origins to a moment in time in 1946 when President Truman's trip to the top of the Washington Monument helped him see the problem clearly.

President Truman had been a road builder earlier in his career. He always loved to drive, became president of the National Old Trails Road Association in the 1920s, built roads as County Judge (an administrative position) in Jackson County, Missouri, began paying dues to the American Road Builders’ Association (ARBA) in the mid-1930s, and had driven between Missouri and Washington many times on U.S. 40 (the Old Trails Road). On May 7, 1946, ARBA presented President Truman an honorary life membership in appreciation of his activity and interest in local and national highways. Participating in the event, left to right, are: - front - Charles M. Upham, engineer-director, ARBA; President Truman; James J. Skelly, president, ARBA; J. T. Callaway, president, ARBA Manufacturers' Division; D. W. Leonard, chief highway engineer, Jackson County, Missouri; Representative J. W. Robinson (Utah), chairman, House Committee on Roads; and Major John A. Long, manager, County Highway Officials Division, ARBA. (Road Builders' News, May 1946).