| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |

The Trailblazers

Federal Highway Construction - - Western Regional Office

By

Eric E. Erhart

In 1916 Charles Sweetser was appointed as a Public Roads representative in California. Records of action during World War I are not complete and little is recorded that occurred during this period. In 1919 Mr. Sweetser returned from the service and was in charge of old District 2 in San Francisco. During this time Public Roads shared office space with the Forest Service which was a natural relationship since both organizations were part of the Department of Agriculture. Further a Congressional limit of $5,000 per mile on Forest Development roads started Public Roads on an extensive program of western highway construction.

In 1916 work was underway on the Salmon River in the Klamath River area. Vernon Bonner was chief locator, assisted by officeman J. L. Mathias, Charlie Morris, my brother Henry and two others named Peters and Grant. Henry Erhart left shortly thereafter and transferred to the Forest Service where he spent all his working career. Charlie Morris was supervising engineer and traveled in and out of the Klamath country from the an Francisco office.

The early years were formative. Education and experience were sparse. Many operations began by off the seat of the pants methods. After World War I the Klamath River Road was the big project. Everyone eventually went to the Klamath which left impressions never forgotten. In 1975 road building on the Klamath was still in progress. In 1919 I went to work in the timber wilderness of the Klamath River in northern California. Eastern entry to the area was from railhead at Montague just off the Shasta River in Siskiyou Country and Arcata or Eureka from the west on the Pacific Coast in Trinity County. Pack animals and foot were the only access for the first survey and construction sites.

A construction crew began working in the north at Happy Camp and another crew started at Orleans. In addition a survey party worked from the Orleans end.

Howard Bentley was the first project construction engineer on the Orleans job followed by Bob Heaney. In 1920 Jack Obermuller became resident engineer. Monty Potter was transitman, W. L. Klien, cook, A. N. Bennett, chainman, and I served as chainman. Obermuller also had his young son at the camp. Both Obermullers later went to work for the California Division of highways. Also working for Jack were Frank Bonnickson and Henry Garber who started on May 20, 1919. In 1921 the crew was expanded to include Dan O'Leary, cook, C. Hom, stakeman, Julius Brannan, officeman, J. Patterson, axeman, and Guy McMurtry, assistant resident engineer.

Many of the personnel hired were local inhabitants of the work area. Examples were myself (my father was a hydraulic gold miner) and Julius Brannan whose father was a supervisor in the Klamath Forest. W. L. Klien was also a Siskiyou County native.

In 1922 I was reassigned to surveying at Big Bear Lake in the San Bernardino mountains. W. L. Klien and J. E. Jensen were on the crew. Jensen finally died after a third attack of acute appendicitis. In 1923 B. L. Elliot was added to the crew and I had been promoted to transitman. The first construction in San Bernardino County was underway, a big job 10 miles long called the Deep Creek cutoff. The mountains were steep and hard granite to compound the problems.

About the same time (1920) work was started on the Angeles Crest Highway, near the present Mt. Wilson observatory. Henry Alderton, and Henry Garber were early crew members.

Development of the lower Southern California forest roads began in 1923. J. L. Mathias was assigned as chief of party on the Mt. Laguna project, a rough granite hogback between the Pacific Ocean and the below sea level valley of the Salton Sea.

One of the first right-of-way grievances occurred in 1925 on resident engineer Rudy Therion's project. A right-of-way deal to cross an Indian family's land was made by BPR. The financial settlement was made but no mention was included for three fences on the property. First the contractor tore down the fences. The lady of the house persisted and rebuilt the fences. The contractor then detoured his operation around the fences. The following Spring, Rudy sent me up to the work site to see the contractor remove the fences. The contractor tore down the first fence and hauled it to the dump. I started taking down the second fence and the woman came out and chased me off with a 2 x 4 club.

I promptly phoned Rudy to come out and take care of his problem. The local residents backed up the woman and the Bureau finally raised money to buy fencing material which was installed by unpaid volunteers. The happy ending - no claim was submitted by the contractor.

In the Spring of 1926 Tom Roach hired on in Yosemite Park as transitman for Harry Tolan. This was the first year of construction in the National Park system. Tom was a big, affable football player from the University of Nevada, who had also been doing some hard rock mining in the Nevada City gold country.

Tom was later in charge of driving the Wawona tunnel in Yosemite. One of his favorite stories is telling how they had cut a window in the tunnel wall to outside air. This permitted the tunnel air to exhaust immediately after each successive blast permitting the crew to start working sooner. On one occasion Tom thought about standing in one of the windows when a shot was fired. On second thought he set a loaded wheelbarrow in the window. When the shot went off, the wheelbarrow was blown into oblivion in the next canyon.

Later on Tom was employed as a tunnel engineer on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, then went to Nigeria as engineer for an international construction company. On returning from Africa, Tom became Division Engineer in Indiana, then Director of Federal Highway Projects in San Francisco until his retirement in Sacramento, California.

My first trip to Arizona was in 1926. At this time, Arizona was a separate sub-district with headquarters in Phoenix. Chris Morrison was in charge and Gerald MacClain was his assistant. I reported as typical of the days past to the project on Saturday. O. D. Bruning with headquarters in Globe was project engineer for the Pleasant Valley-Holbrook Road which began at Globe, followed up the east side of Roosevelt Lake, through the old Cherry Creek massacre country up over the Mogollon Rim (of Zane Grey fame) and down the rim pine forest to Holbrook. Budgets were still very limited and a request for field project pencils sent someone into the Phoenix drafting room to collect all the old pencil stubs for project use. A further request for drafting paper resulted in receipt of paper used on one side with instructions to utilize the unused side.

This extreme conservationism lasted well beyond the mid 1950's. Recalling a similar pencil story, the project engineer kept all his project supplies locked in a field chest. One being cajoled into opening the safe to release some pencils he would go into a tirade over "what do you crew men do with all the pencils?" On a pencil encounter one morning the office-man inquired "Boss, don't you know what Government employees do when they retire? "No," he retorted. The reply, "Boss, they sell pencils."

1927 looked like a year when very tall western top hats were in vogue. I (officeman), Leonard Henderson (day laborer), J. E. Jensen, and Julius Brannan (party chief) were assigned to the north rim of the Grand Canyon to survey an access road from Fredonia (Jacobs Lake) into the park.

Julius Brannan was chief of party and had set up camp with a large variety of World War I surplus equipment. All tents were different sizes, shapes, and color so the camp was a polyglot affair. To compound matters, water had to be hauled over a rough road for 35 miles. Anyone over-using water was looked at with a jaundiced eye.

One day Mr. Norcross, then chief of Forest Service, inspected the camp and project. He was quite critical of Brannan for spending too much money on the camp. We week later Thomas McDonald, Dr. Hewes, B. V. Finch, and some Forest Service personnel showed up at the camp. When Thomas MacDonald was introduced to Brannan he commented "You have the dirtiest camp in the United States." As a result of camp conditions, Mr. MacDonald went back to Washington and send out a nationwide request to find out if uniforms could be adopted for all Bureau crews. The replies were somewhat negative and this was as close to dress alikes as the Bureau would ever come. The newly designed uniform went to naught.

Before leaving camp Mr. MacDonald advised Brannan to tell Chief of the Forest Service Norcross to "Go to hell" since they hadn't overspent in setting up the camp.

In 1927, Lance Bartell hired on as chainman for Part chief J. L. Mathias at Lassen Park. Work was becoming widespread across the western headquarters and money was spread very thin.

In 1928, George M. Williams, later to become Director of Engineering and Operations at the FHWA headquarters, transferred from Denver to San Francisco. His first assignment was to report to Julius Brannan as officeman on a Sequoia Park project. I picked up George at the post office, dropped him off on the wilderness trail and pointed him in the direction of Brannan's camp. Needless to say he found his own way to camp.

When World War II came on, the regular road program was severely curtailed. Personnel were deployed to the military, defense access roads, airport construction, defense plants, the Alaska Highway, and the Panama crossing.

In 1942, I was placed in charge of Location and Design in the Southern Division on the Alaska Highway. This included the section from Dawson Creek to Fort nelson, and living was very primitive. Assigned with me were Joe Hillman as party chief and Howard Baugh as transitman.

At this time, many personnel were somewhat at loggerheads with Joe Barnett (father of the modern freeway) in the Washington Office. There were two schools of thought, one for and one against spirals on highway curves. While the uniform acceleration changes concept may have been valid for fixed rail transit it was always questionable when applied to the movement of non-restricted rubber tired vehicles. The State of California eliminated the problem by reducing curvature until the spirals were of no value. High standards of construction have all but eliminated spirals. I did my last job on the mountains in 1955, a reconnaissance for the future Mill Creek project. Work continued in the Big Bear vicinity until about 1960. The resulting highway system provided access to prime winter and summer recreation in the desert with easy access to a 12 million metropolitan population.

In 1955 I went to Washington as Chief of Federal projects Division. After eight years on the job, I retired and after another eight years of procrastination moved back to California (the promised land).

In 1955, methods of gaining access to difficult survey sites were projected into the 20th Century with the utilization of helicopters to take personnel and equipment to the work site. Aerial surveying also came on strong resulting in a tremendous drop in manpower requirements for location and design. These were followed by computers, electronic calculators and electronic measuring equipment. All made work faster but sometimes the shakedown to operational status was painful as techniques for increasing accuracy were developed.

Aside from Thomas MacDonald being a Scotchman duly dedicated to building on a pay-as-you-go basis, the immense scope of making all of the west accessible was a gargantuan task. At the time the BPR was opening up wilderness, the States were totally committed to service the population centers, connecting population centers and building the farm-to-market routes. The very limited financing always was a challenge and a compromise whether to build a short section of the best road or to stretch the budget to build a road between two population centers. Naturally, a road to connect two places won out, as a part of a road had almost no economic value. As a result it was always a budget struggle to do a credible job. In that light there probably was good justification in the saving philosophy, even filtered down to the conservation of paper and pencils.

If the economics of the 1920's seemed tough, it was just a primer for the economic strife of the 1930's. There was, however, a bright spot - in the quality of personnel on the job. Graduate engineers were assigned from brush cutting through every level of administration. Almost everyone started at the bottom and worked up so they had a thorough knowledge of the highway business.

With the beginning of the war in 1941 personnel were deployed to every phase of the war effort. The Alaska highway construction took all available personnel.

Klamath River, Calif., Reconnaissance 1919 Levant Brown, unknown horseman, Eric Erhart

Klamath river, Calif., Engineering Crew 1921: Upper (L-R): Jack Obermueller (1st Project Engineer on Contract Construction in the Region), Henry Garber, Monty Potter, Eric Erhart, Julius Brannan, J. Patterson, Guy McMurtry Lower: Dan O'Leary, C. Horn |

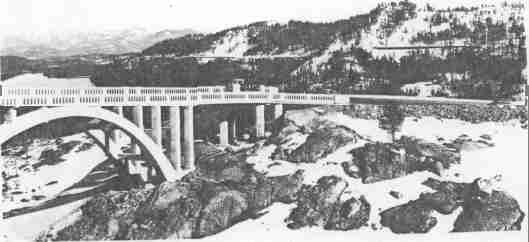

Donner Pass Historical Site Bridge Constructed by BPR in 1926 Cy Bruning, Resident Engineer

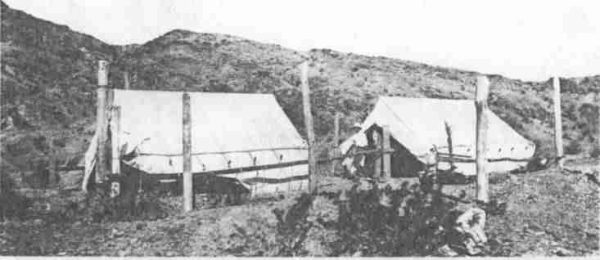

Typical Desert Survey Camp 1933 Blythe - Vidal, Colorado River

Commissioner MacDonald - Peace River Bridge 1943

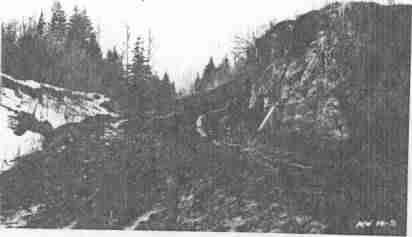

Fort St. John - British columbia First Stage of Alcan Highway 1943

Public Roads Administration Engineer's Office Ft. St. John 1943 - 50° below zero