Firing Thomas H. MacDonald-Twice

by

Richard F. Weingroff

The Firing: #1

Official portrait of Thomas H. MacDonald |

In 1910, while serving as Iowa's State Highway Engineer, Thomas H. MacDonald became annoyed with the U.S. Office of Public Roads. He was one of many highway officials throughout the country who had been "hired" as Special Agents to collect data on roads and provide it to Washington--at a salary of $1 per year. However, his appointment was terminated suddenly, before the data was compiled, and instead, C. S. Nichols, another member of the Iowa State Highway Commission, had been appointed a special agent at $60 a year. MacDonald replied on September 6 after being informed of the termination:

If I understood our previous arrangement, I was to co-operate with your department in collecting material relative to mileage, expenditure and such information concerning the roads and the state and Mr. Nichols was to receive the appointment of special agent to support you with material relative to the activities of various kinds in the road improvement lines in this state.

He added:

It seems to me that my appointment as special agent should hold until after the data is collected which we are gathering in conjunction with your department. It will take some time yet to finish collecting this material and Mr. Nichols will not be able to take any part in that work.

The Office received the letter on September 8. Director Logan Page replied the next day:

In reply, I beg to state that you are entirely correct in your understanding of what our arrangement was, and it was an oversight on the part of this Office that your appointment at $1 per annum was revoked.

I regret very much that this has happened, but am today having you reappointed as Special Agent at $1.00 per annum, and will forward your reappointment as soon as same is received from the Secretary's Office.

Thus, the agency had the dubious distinction of firing, at $1 a year, the man who would later head the agency for 34 years--and transform the country while doing so.

The Hiring

Photograph of Thomas H. MacDonald used to illustrate an article in the November 1923 issue of El Automovil Americano |

Following Page's death on December 9, 1918, MacDonald emerged as the leading candidate to serve as Chief of the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR), as it was now called. MacDonald had the support of the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO), which had recommended him for the job. However, the compensation of $4,500 a year, the same as his salary in Iowa, caused MacDonald to hesitate to take the job.

Having discussed the position with his wife, MacDonald concluded that while the opportunity was great, he could not give his full effort to the work if beset by financial worries. He also felt that less of a discrepancy should exist between the salary of the head of the Federal highway agency and the chief engineers of the principal State highway departments. It soon became clear that Congress would approve a salary of $6,000 a year, the amount MacDonald felt would accommodate the higher cost of living in Washington and the additional expenses he would incur in discharging his responsibility to foster friendly relations with the State highway departments.

MacDonald, however, wanted one last assurance before accepting the position. He was concerned about the BPR's reputation among State highway officials. Relations between the States and BPR had been strained by Page's insistence on adherence to Federal requirements, impatience with those who disagreed with his scientific views, and encouragement of rigid oversight and enforcement by field staff-what historian Bruce E. Seely referred to as the BPR's "overzealous and inflexible federal engineers." (Building the American Highway System: Engineers as Policy Makers (Temple University Press, 1987). MacDonald wanted the flexibility to repair the rift.

In a letter to the Secretary David Houston on March 20, 1919, MacDonald stated that he wanted to ensure he would be able to make the adjustments needed to "assist in changing the present attitude of criticism toward the Department and to insure the cordial co-operation of the state highway officials . . . ." The changes were decentralization of responsibilities to the District Engineers; increased salaries for the District Engineers to retain their services; adoption of the "most liberal policy possible" in interpreting existing laws to get construction underway rapidly; and provision for an advisory committee, to be selected by AASHO, to help improve Federal-State relations.

These conditions being acceptable to Secretary Houston, he sent a telegram to MacDonald on March 25, 1919:

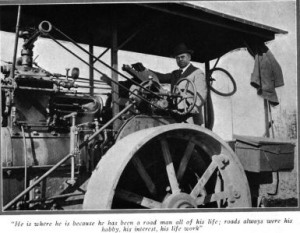

This photograph, showing Thomas H. MacDonald operating road equipment in a coat, tie, and hat, accompanied an article about him, "At His Nod Millions Move," in the June 1922 issue of Motor Life. The article by C. H. Claudy describes him: "Rather heavily built, a round, grave, but humorous face, high forehead, hair thinning . . . a level, pleasant voice, and an incisiveness of speech and ability to say what he wants to say in a few words and make them all count." |

Glad to cooperate with you along lines of our conference and your letter. Would it not be possible for you to assume your duties here first of April. Situation urgent on account of nearness of construction season. You could make occasional trips to Iowa and give constant advise from here. We could take steps to expediate work and arrange for conference in West which I think ought to be held. [Spelling as in original]

MacDonald was appointed on April 1, 1919, "engineer in immediate charge of the work under the Federal-aid road act." When the salary of $6,000 was confirmed, he was appointed "Chief of Bureau" on July 1, 1919. In the years ahead, his title would change several times, but he would retain the nickname "The Chief."

The Firing: #2

Through the Administrations of Presidents Woodrow Wilson (D), Warren G. Harding (R), Calvin Coolidge (R), Herbert Hoover (R), Franklin D. Roosevelt (D), and Harry S. Truman (D), MacDonald remained The Chief. In 1951, the Commissioner of Public Roads (MacDonald's official title) had reached the government's mandatory retirement age of 70 and had, therefore, formally retired. However, because of the emergency situation during the Korean War, President Truman persuaded MacDonald to stay on as interim head of the BPR. The President thought it would be best to retain MacDonald, the most respected man, nationally and internationally, in his field.

When President Dwight D. Eisenhower took office in January 1953, MacDonald planned to retire in the summer of 1953. Instead, he retired on March 31. He had been fired. Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks (whose Department housed the BPR) realized that MacDonald, with his decades of service and close relationship with the congressional public works committees had an independent pipeline on legislative and policy issues. With the Federal-aid highway program accounting for half the Department's budget, Secretary Weeks wanted to take control of policy decisions on the new Administration's behalf.

Therefore, he signed Departmental Order No. 128 on February 13, 1953, creating an Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation. The Under Secretary, Robert B. Murray, was to be "the principal adviser to the Secretary on all policy matters concerning transportation within the Department and on all matters concerning the transportation policies of the Government." He would also, "Exercise direction and supervision of the . . . Bureau of Public Roads . . ." as well as the other transportation-related agencies within the Commerce Department. Moreover, all the authority and program functions vested in the head of the BPR and the other Agencies, "are hereby made subject to the supervision and coordination of the Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation."

Engineering News-Record, in its issue of April 2, 1953, put it this way: Secretary Weeks "has no intention of letting that amount of [Federal-aid highway] money go out without supervision from the top."

MacDonald's assistant, career BPR employee and future Federal Highway Administrator Frank C. Turner (1969-1972) recalled the firing in a 1988 oral history interview conducted by John T. Greenwood for the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Turner's recollection provides a glimpse behind the Secretary's understandable desire for control of policy and pursestrings:

This photograph of "Roadman MacDonald" was used to illustrate an article in Time magazine (May 1, 1939) about release of the report, Toll Roads and Free Roads, to Congress. |

Mr. MacDonald was still the Chief of the Bureau at that time. One of the first things that happened was they called for Chief MacDonald's retirement. He had already reached retirement age and been extended in his job . . . . But when Ike came in, there had been some difficulties and some loud criticism of Public Roads up in the state of Massachusetts-in connection with Massachusetts was not being dealt with fairly. They were not being properly graded in their accomplishments and the grading that they were talking about was the maintenance reports . . . . Each State was ranked [based on maintenance of Federal-aid highway projects, which was the financial and operational responsibility of the State highway agencies]; we sent reports back to each State showing their ranking . . . . Somebody in Massachusetts got a hold of one of those and didn't think that Massachusetts' grade was as high as it ought to be compared to some of his neighbors. He had no idea how the thing was handled or what it represented or the importance of it; but anyway, Massachusetts wasn't getting a fair shake out of the federal government on highways. The Bureau was to blame and Mr. MacDonald was the Chief of the Bureau.

So . . . when Ike came in, Ike appointed as Secretary of Commerce, Sinclair Weeks, who had been mayor of one of the towns [although Weeks had not been a Mayor, he was a well known Republican Party supporter from the State] . . . . When the announcement was made, he was besieged immediately by this critic up there who was criticizing the highway program then and the Bureau's treatment of Massachusetts. Weeks had taken this on as a cause. At the same time there was a constituent up there in Massachusetts, the guy was advertising and promoting (very heavily) a . . . battery additive . . . all you did was buy a bottle of this stuff and pour it in your battery and it automatically will restore the battery to full strength. It had been sent to the Bureau of Standards [which] tested it and found that it was a pure fake . . . .

So when Weeks came in, the Bureau of Standards is in the Department of Commerce, Public Roads is in the Department of Commerce, in order to show that he was on the side of the constituents there, they are going to straighten out the mess in Washington. These were the code words . . . . So Weeks comes down with this chip on his shoulder, this mandate. The first thing he does is to fire the head of the Bureau of Standards, who was a highly respected technician . . . . He fired him and he fired MacDonald. He called MacDonald over and fired him like that. Chief came back and was ordered to be out of the office the next day. So was the Director of Standards. Well, these things hit the headlines, of course. The firing of the Bureau of Standards Director was really a hot one. The Chief wasn't so bad because he already had been there a long time and he was expecting to retire anyway.

Caricature of Thomas H. MacDonald used to illustrate "The National Gallery" feature in The Washington Post, June 20, 1934. The brief article describes him: "Blue-eyed, canny, he hugs his desk but gets enthusiastic over the open spaces. Likes to pound rocks, hunt for road sites and breathe ozone." |

Turner recalled the resulting uproar, especially among the scientific community regarding the Director of Standards. But he also recalled that Weeks "had sense enough to realize that, he had gotten himself out on a limb . . . . Weeks used to have all the walls [of his office] plastered with dozens and dozens of cartoons of himself over this battery additive thing and a number of them on highways, the firing of MacDonald." Turner continued:

When the Chief came back and announced to us that he was retiring as of 5:00 that afternoon; that he was leaving town the day after; of course we had these long faces around there and I and everybody else was asking what happens next? I was particularly concerned because I was the assistant to the guy. They only had two of us as assistants to the Commissioner and I was one of them. I thought my goose was cooked, of course.

MacDonald's replacement, Francis V. du Pont, arrived and "didn't bring a single person with him. He didn't even bring a confidential assistant secretary into his office." Turner recalled that du Pont, "came in and announced himself just as plain and humble as anybody you ever saw. Of course he drew the immediate loyalty of everybody in the place. He never changed. He supported everybody." As for Turner's fate:

He called me in and he said, "I guess you figured that-you probably thought I was going to fire you or eat you alive or something," he said. "But I looked up your record and talked to people in the state [Delaware] about you and all the rest of the people who are working here and," he said, "I'm satisfied-just go on doing what you're doing and tell me what I'm supposed to do here. I don't even know where the bathroom is."

MacDonald, whose first wife Bess had died in 1935 after a 2-year illness, also did one other thing that Turner didn't mention. As Tom Lewis put it in Divided Highways: The Interstate Highway System and the Transformation of American Life(Viking Press, 1997):

After learning the news, MacDonald returned to his office and told [his secretary] Miss Fuller, "I've just been fired, so we might as well get married."

In speaking to the press prior to leaving office, MacDonald stressed the importance of the Federal-State partnership:

[It] is a workable plan to accomplish a continuing program that involves both local and national services; second, it sets a pattern in harmony with the concepts of federal government.

He traced the partnership to the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, telling reporters:

[It] recognized the sovereignty of the states and the authority retained by the states to initiate projects. All through the legislation since then, the same mechanism of checks and balances has been maintained evenly so that the states and the federal government both have to agree before they can accomplish a positive program.

Thomas H. MacDonald examines the sample that served as a model for the black-and-white shield that would be placed along the Nation's main interstate roads following approval of the U.S. numbered highway system in November 1926 |

The condition of the Nation's roads was, as ever, very much on his mind. The original Federal-aid system, designation of which had been authorized by the Federal Highway Act of 1921, had been surfaced for the most part by the mid-1930's, but only to the standards necessary for that period. Now, those same roads remained in use but society expected them to provide at least eight times the service as they were designed for. Less than 25 percent of the Interstate System as designated in 1947 was adequate for modern traffic (assuming, as everyone did at the time, that construction of the Interstate System meant upgrading the U.S. numbered highway in the corridor to meet the limited standards adopted in 1945). About 16 percent of the System was "critically deficient."

To meet growing needs, he told reporters:

It is logical to borrow for important needs and to retire the borrowings from user income. By setting aside the income from a fraction--say a cent of the gasoline tax, there is an assured fund that can be used to retire bonds.

As always, though, his attitude toward toll roads was cautious:

Financing toll roads with bonds paid for entirely out of revenue [tolls collected on the road] can lead us into a dangerous situation. Only certain stretches of heavy traffic roads, like the New Jersey Turnpike, can be self supporting on that basis.

Issuing bonds backed by earmarked gasoline tax receipts was one way of paying the difference between bond charges and toll collections.

Noting that the Federal Government collected $800 million a year in fuel tax revenue but provided funds to the States at a rate of only $575 million, he thought it "desirable to equate federal aid to federal gas tax revenues." He was not, however, convinced that all Federal highway user tax revenues should be dedicated to highways, citing excise taxes on such products as perfume and alcoholic beverages as examples of taxes levied simply to meet government expenses. "Take the cigarette tax," he explained. "I don't know how you would apply its proceeds for the benefit of cigarette users."

Drawing of Thomas H. MacDonald used to illustrate a feature article ("Real Workers in the National Capital" by Herbert Corey) in Washington, DC's The Sunday Star of February 17, 1924. The article describes him: "Rather short, stocky, black haired, a bit stand-offish at first, likable at second time of meeting." |

A reporter asked MacDonald if general reductions could be achieved in road expenditures if the use of highways were restricted to lighter vehicles. MacDonald replied, "We start off on an absurdity." He explained, "I've never subscribed to any part of that theory. If we didn't have to support an army all our taxes could be reduced." He added that even if it were possible to ban commercial carriers from the highways, officials would still have to build the roads for heavy traffic as a national defense measure.

MacDonald stayed in Washington only 1 more day. On April 1, 1953, he looked on as Secretary Weeks administered the oath of office to new Commissioner of Public Roads du Pont. That same day, MacDonald left for College Station, Texas, where he would work part time to help Texas A&M College System and the Texas highway agency develop a transportation research facility now known as the Texas Transportation Institute. He also married Caroline Fuller.

AASHO's magazine, American Highways, summed up the highway community's view of The Chief:

In his retirement from the public service, it can properly be said that it marks the end of an era of highway progress of proportions undreamed of at the time he assumed office. Unquestionably, America's leadership in the highway field, and highway progress in the years to come to a considerable degree, will be a reflection of the vision and integrity of Thomas Harris MacDonald.

On April 7, 1957, The Chief died of a heart attack in College Station at the age of 76. He had spent the evening with his family and his friend and associate, State Highway Engineer Dewitt C. Greer. Greer described the end: MacDonald "walked over to the cigar counter after a very pleasant dinner with his family and friends and bought a cigar, sat down on a comfortable divan and passed away."