Dr. S. M. Johnson - A Dreamer of Dreams

by Richard F. Weingroff

|

| S.M. Johnson |

Introducing Dr. Johnson

Dr. S. M. Johnson was proud of his Virginia roots. However, his family had joined the westward movement of the 18th century when his grandparents moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1832. After a childhood in country or village homes, he graduated from Parsons College in Fairfield, Iowa. At Princeton University, he earned a literary degree in post-graduate studies, before graduating from McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago, Illinois.

He served as a Presbyterian minister for 18 years in Corning, Iowa; Denver, Colorado; and Chicago. A biographical sketch by C. H. Huston, president of the Lee Highway Association, explained how these years shaped the man:

The activities of those eighteen years developed the qualities of altruism, leadership, the ability to build up and direct an organization including financial operations and ability as a public speaker and a writer, all of which Dr. Johnson possessed in such degree that he became known nationally and internationally. Calls to service led him out on trips throughout the country-north, south, east and west, until he came to know the United States as a whole and to think, speak and act in terms of the national life.

These years of achievement came to an abrupt end in Chicago when Dr. Johnson experienced a nervous breakdown that "compelled an absolute change to life in the open air," according to Huston.

Dr. Johnson moved to Charlotte in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, where he lived for 7 years. Finding little success on a cotton plantation, he became a land developer whose chief problem, as Huston put it, was "transportation-how to extend the pavement of the Charlotte streets to the suburban tract he platted." When local governments would not provide the pavement, he built the roads himself to serve the land he was developing.

While in Charlotte, he married Ida Vail, whose father had been an officer under General Robert E. Lee during the Civil War. Her father also was Chairman of the Board of Road Commissioners of Mecklenburg County for 30 years. Mecklenburg County had been a good roads leader under an 1885 State law that allowed the county to collect a small property tax for road improvement. Miss Vail's father had, according to Dr. Johnson, built the first mile of macadam road in the South.

The young family moved to Lincoln County, New Mexico, where they established a ranch to grow apples in the Ruidoso Valley. Again, Huston fills in the details:

Isolated on the ranch and compelled to make a living out of the soil where most of the proceeds of sales were consumed by transportation costs, he learned through hard experience what a heavy burden the nation's producers were under for lack of proper facilities for highway transport. It was thirty miles over mountains to the nearest railway station, seventy-five miles to the nearest town of any size and one hundred and fifty miles to El Paso, Texas, the nearest city affording a market for the choice apples which were the main product of the ranch. In Charlotte he had learned the vital necessity of pavement from the business center to the suburb; in the far Southwest he learned the value of the road from farm to market.

Although Dr. Johnson faced "years of privation, hardship and labor to make ends meet," the experience proved to be a "forge, heated to white heat" that turned him into an apostle of good roads.

The Apostle of Good Roads

In 1910, he and Dr. J. W. Laws organized the Lincoln County Good Roads Association to improve the area's roads. He helped secure approval of a good-roads bond in a county election. And much to the amusement of the county's old timers, he predicted that one day, a transcontinental highway would traverse the county. According to Huston, the prediction had been inspired by a joke:

In the closing hours of Congress more than a decade ago, in the time just before adjournment given over to jokes and chaffing, Representative Broussard of Louisiana had sprung a joke in the Lower House by moving that the Government build five transcontinental highways along parallels of latitude, one of which was the thirty-second. The wires flashed the joke over the country, the "El Paso Herald" carried it to the ranch under the thirty-second parallel where Dr. Johnson read it. He then resolved he would devote the remainder of his life to making that joke a reality.

Several ideas had formed in his mind. He was convinced the automobile would change America in the 20th century as dramatically as the railroad had in the 19th century. Roads were needed to serve this new means of transportation, and he was convinced they should be built according to science, not in the haphazard fashion that was common in rural areas. They should be arranged according to function in a system of main trunk lines and laterals according to the service each would provide. The Federal Government should help the States build the roads. In addition, the Federal Government should help States that have large amounts of nontaxable public land, such as New Mexico, pay for roads across the public reservations.

His first efforts, from 1910 to 1912, focused on constructing a road linking Roswell, New Mexico, and El Paso, to be called the Borderland Route. He helped secure changes in State law to get the work underway.

These early successes led to his selection as a delegate to a February 1913 conference in Asheville, North Carolina. Led by Governor Locke Craig of North Carolina, 15 southern Governors had appointed commissioners to select a route for a southern transcontinental highway from Washington, D.C., to California, to be called the Southern National Highway. With Dr. Johnson on hand, the commissioners included his Borderland Route from El Paso to Roswell.

While in the East, he attended the Second National Good Roads Federal Aid Convention on March 6 and 7 at the Raleigh Hotel in Washington. The conference was sponsored by AAA to discuss plans for Federal involvement in road building, then under consideration in Congress. Dr. Johnson spoke on the subject of Federal help for public lands States. Although the Convention did not adopt a resolution on the subject, his presentation helped him gain national recognition and the friendship of many leaders of the good roads movement. One of those new friends was Senator John H. Bankhead, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Post Offices and Post Roads.

The $29 Million Apples

On November 9-14, 1914, Dr. Johnson was one of 5,000 delegates to the Fourth American Road Congress in Atlanta, Georgia. The Congress was sponsored by AAA and the American Highway Association, an umbrella group of good roads boosters formed by Logan Waller Page, Director of the U.S. Office of Public Roads (OPR). During a discussion of a presentation on convict labor, Dr. Johnson addressed the group. He described his background, explaining that he was a minister of the gospel who had experienced a nervous breakdown that changed his life. He said that "being unable to take up the active work of a pastorate, I have given the most of my energies to promoting the gospel of good roads."

We have called upon the United States government to help us out of the mud. We have appealed to the boys and girls of our high schools to help us. We are not getting the cooperation of the ladies and I tell you it is time to ask the ministers and priests of this country to enlist in the campaign for good roads.

He knew the text:

Does not the Good Book say to make the crooked straight and the high places low and the low places high and to make smooth the way of the Lord? It is time that we interpreted that rightly. Does it not say that we live and move and have our being in Him? Well, the moving is pretty tough in some places and therefore good roads have a great deal to do with religion.

Then, he said, he wanted to show the convention some apples. Huston explained how Dr. Johnson, the apple grower, made his presentation:

[He] slowly removed a tissue-paper wrapping from a marvelously beautiful red apple five inches in diameter. He unwrapped and displayed another, then a third. The three, laid in a row on the speaker's desk, spanned over thirteen inches.

He told the delegates the applies had been grown in the White Mountains, a few miles west of Roswell at an elevation of 5,750 feet-and 25 miles from the nearest shipping point. Because the surrounding land had been set aside as Lincoln National Forest, "it is impossible for us to tax it to build roads." He explained:

Now I am feeding apples like these to the hogs of Lincoln County, because the United States government has not thus far lifted a finger to improve the roads across its own land.

Dr. Johnson commented on the term "Federal-aid," which was in common use as the government considered creating a road building program. He said that for him, the term meant something different than its usual interpretation of government aid to State or local governments for better roads:

It means that we frontiersmen out in New Mexico have to aid the United States government to make the roads. Last summer I took my car and three men and went and fixed the impossible places on Uncle Sam's domain in the Lincoln National Forest on my way to my market and shipping point.

The Federal Government also had not improved the road across the Apache Indian Reservation, which Dr. Johnson indicated was the worst stretch of the Southern National Highway. He convinced Otero County to give him $1,000 and he fixed the road "on Uncle Sam's Indian reservation."

He was all for through roads and better roads elsewhere. The through roads would allow people to come "and see and get well and help us develop the magnificent boundless resources of our great West." The Federal Government, as far as he was concerned, was looking at the problem with one eye when it needed to use both:

When we find that the United States Office of Public Roads is simply a branch of the Department of Agriculture, we say that the Office of Public Roads should be a department by itself and we should have the through routes that are as essential to the development of our great country as it is that the farmer should have his. We want you to have your roads, that is the thing for Georgia and Iowa and the farming States, but we want you to help us to get our roads that are vital to the development of our country.

The American Road Congress adopted a resolution in support of his goal:

Resolved, That the federal government be urged to build highways across all Indian and forest reservations and all other federalized areas, where such connecting links are essential parts of established through routes of travel.

On July 11, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson approved the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which established the Federal-aid highway program. A leadership committee of the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) had drafted the basic bill, which Senator Bankhead introduced at the urging of OPR Director Page. It authorized $75 million in Federal-aid to the States over 5 years for road building. An amendment introduced on May 1 by Senator Thomas James Walsh of Montana was included. It authorized an additional $10 million-$1 million a year for 10 years-for roads and trails within or only partly within the National Forests. The funds, Senator Walsh explained, were to come from receipts for the sale of timber, fees for grazing privileges, and all other receipts from forest reserves (then about $250,000 a year, but he expected the total to increase as roads were improved).

Huston, who included photographs of the three apples in his booklet, noted:

Since then a total of $19,000,000 has been appropriated [in addition to the initial $10 million] for this purpose and the policy has been fixed whereby the work will continue until completed. Dr. Johnson shows his friends the tree upon which three apples grew which were sold for $29,000,000.

Along the Southern National Highway

In 1915, leaders of the Southern National Highway in California made the first official trip over the highway from San Diego to Washington. Financed by the Cabrillo Commercial Club, the motorists included Colonel Ed Fletcher, a leading San Diego booster; William Gross, an associate of Colonel Fletcher's; Wilbur Hall, a magazine writer; and Mr. B. H. Burrell of the OPR. Burrell joined the tour after Colonel Fletcher asked Page to provide an official observer. Mr. Harry Taylor, their chauffeur, was an employee of Fletcher's who would marry his oldest daughter Catherine. The group left San Diego on November 2. On November 8, they expected to travel from El Paso to Roswell in 1 day. The trip report by Gross explained that "soon after we started out from El Paso our hopes went a glimmering as the conditions of the road did not admit of fast driving."

They reached Ruidoso where they spent the night at the White Mountain Inn. There, they met Dr. Johnson, "a prominent good roads booster and State Organizer of the Southern National Highway Association for New Mexico," according to Gross.

Dr. Johnson had been notified of our coming, and had been out hunting all that day, hoping he would be able to treat us to some venison steak and wild turkey. We knew the Doctor's intentions were good, but we had to satisfy our appetites with just a plain chicken dinner.

The next day, Dr. Johnson took the group on a tour of a prehistoric irrigation canal that ran through his property for several miles. He had written an article about the flume for Engineering News (March 25, 1915).

The group reached Washington on November 27 after a 3,247-mile journey. The OPR's Burrell reported that the Southern National Highway is "a feasible highway, which could be traveled at the present time without undue hardship or difficulty." Nevertheless, the Southern National Highway and the association formed to back it failed. The route would become the Broadway of America, with Colonel Fletcher as vice president of the Broadway of America Highway Association. It, too, would never become a major, nationally known highway.

Dr. Johnson learned from the experience as he went on to other projects.

After the Great War

The Federal-aid highway program established in 1916 was hindered the following April when the United States entered the Great War in Europe, now known as World War I. The war effort drained resources and men that could have been used to implement the new program of road building. At the same time, the war opened the U.S. Army's eyes to the value of motor vehicles in wartime. While the movement of trucks to ports in the United States had caused the roads to deteriorate, the excellent roads of France had demonstrated the potential of road transportation for military purposes.

Shortly after Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, Dr. Johnson attended a reception for national good roads leaders in Washington. He proposed that the Federal Government-which had accumulated the largest fleet of motor trucks in the world during the war-transfer the surplus military equipment to the States for highway work. He then drafted a bill for Senator Bankhead to introduce. Congress approved a series of bills that directed the Secretary of War to transfer to the Secretary of Agriculture all surplus vehicles, construction equipment, and supplies that could be used to improve highways. The distribution of about $215 million in equipment, arranged through the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, was substantially completed in 1925 and played a major part in the improvement of roads during the 1920's. The Bureau retained an additional $7.8 million in equipment for its own use.

On July 7, 1919, the U.S. Army launched its first transcontinental convoy of military vehicles from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco. Dr. Johnson had suggested that the War Department launch a convoy to see if, in an emergency, the Army could move across the United States as it had across France. The Lincoln Highway Association, which had suggested a similar idea, took the lead in working with the Motor Transport Corps to arrange the convoy. Because one purpose of the trip was to spread the Good Roads Movement, Dr. Johnson went along as the convoy's "official spokesman," a representative of AAA, and a guest of the Lincoln Highway Association.

The convoy began after a ceremony that included the dedication of a temporary marker for the Zero Milestone on the Ellipse south of the White House (see related story). The vehicles headed north to Gettysburg and traveled the rest of the way to San Francisco on the Lincoln Highway. At each town and city, the convoy was greeted by dignitaries and residents who wanted to see the soldiers and the wondrous vehicles that had helped secure the victory in Europe. The commander of the expedition, Lt. Colonel Charles W. McClure, would address the crowd at each stop and Dr. Johnson would make his presentation on good roads.

In American Road: The Story of an Epic Transcontinental Journey at the Dawn of the Motor Age (Henry Holt and Company, 2002), Pete Davies provides a flavor of Dr. Johnson's message. In Bedford, Pennsylvania, he proclaimed:

We are crossing the continent to impress upon all leaders of public action in the world that the next step in the progress of civilization is to provide road beds upon which rapid transit motor vehicles may be operated with economy and efficiency. This is true, not only of backward peoples, but also of the most advanced nations, including our own.

In Wooster, Ohio, Dr. Johnson told his listeners:

We are at the beginning of a new era of American progress and history. Now that we have finished the job on the other side [in Europe], the next great job will be the improvement of the highways so that automobiles and motor trucks can be operated on them economically.

In this comment, he was echoing the words of Secretary of War Newton Baker during the ceremony on the Ellipse. "This," Secretary Baker had said, "is the beginning of a new era."

One participant on the convoy, Lt. Colonel Dwight David Eisenhower, considered the speeches along the way to have been one of the biggest hardships the men had to endure. Davies observes that this applied to Dr. Johnson as well as Colonel McClure, Governors, Mayors, and other dignitaries who greeted the convoy at every stop. In Wooster, Davies explains:

Presumably having heard Dr. Johnson's address once too often already, the searchlight crew broke his rhythm when they started playing their beam across the evening sky. Unperturbable, Dr. Johnson plowed on. "We are speaking to the entire family of the nation," he declared.

When the convoy reached Fort Wayne, they were on Dr. Johnson's home territory. Davies summarizes Dr. Johnson's remarks:

When his grandparents had traveled to Fort Wayne in 1832, he said, they'd made 10 miles a day. Now you could go twice that distance in an hour. Already, more people were traveling by car than by train. Already, the nation had 500,000 trucks on the road. Soon, he prophesied, it would be ten times that many. They had to come, and there had to be good roads for them, because "the railway is no longer capable of meeting the transportation needs of the country."

In this speech as in others, one of Dr. Johnson's goals was to generate support for the Townsend Bill. Introduced by Senator Charles E. Townsend of Michigan, the bill would create a National Highway Commission to build a national system of highways. The Commission would also operate the existing Federal-aid highway program to help the State highway agencies improve State roads. The bill, he told his Fort Wayne audience, would mean $20 million from Washington for Indiana's roads.

Dr. Johnson continued this theme along the way. The night before the convoy left Iowa, he told a Council Bluffs crowd that, "Once a road led to somewhere near in the vicinity. Now it will connect the extremities of the country." Only the Federal Government could build such a road. In Nebraska, he predicted that if the Townsend Bill passed, the Lincoln Highway would be paved from Omaha to Wyoming in 5 years.

The convoy reached San Francisco on September 6, 1919. In the final ceremony, Dr. Johnson received one of the gold medals presented by the Lincoln Highway Association to all participants. The men were happy to be there because it meant the end of the bad roads, their toils, and the speeches they had endured for 2 months. Davies provides a finish for Dr. Johnson's work:

Even Dr. Johnson got a cheer-in his case an ironical one for his public admission that, to avoid the worst of the Nevada desert, he'd taken the train from Eureka to Carson City. Then he said once again that every city in the West should back the Townsend Bill; once again, he urged that its projected appropriation for road building be raised to $1 billion.

The Townsend bill would not be adopted. In 1921, Congress approved a compromise under which Federal-aid would be made available to the State highway agencies to improve roads included in a Federal-aid system. The system would include up to 7 percent of the Nation's total rural road mileage, with three-sevenths of the system being "interstate in character."

The Lee Highway

The Southern National Highway, now the Broadway of America, was still on Dr. Johnson's mind. By the end of 1918, he had conceived an idea to build a direct highway, named in honor of General Lee, from Washington to Memphis where it would meet the original line of the Southern National Highway that would take the route through Roswell, New Mexico to San Diego. When he mentioned the idea to AAA officials, they informed him that a movement was underway in Virginia to establish a Lee Memorial Highway. Professor D. W. Humphreys, a professor of engineering at Washington and Lee University at Lexington, Virginia, had proposed extending the Valley Turnpike, the Shenandoah Valley's main highway, to link Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and Chattanooga, Tennessee.

On February 22, 1919, Dr. Johnson, Professor Humphreys, and others met in Roanoke, Virginia, to discuss the proposed memorial highway. An organization was established on December 3, 1919, called the Lee Highway Association, to support Professor Humphreys' idea of a Gettysburg-Chattanooga line. The association also intended to promote extensions to establish a direct route "for pleasure and business" between New York City and New Orleans. Dr. Johnson's idea of a transcontinental highway through New Mexico was lost.

During this period, Dr. Johnson was working with the War Department on the transfer of surplus equipment for highway building, participating in the U.S. Army convoy, and engaging in other matters, so he initially took only a limited role in the proposed new highway. However, Professor Humphreys, the primary backer of the Lee Highway as originally conceived, died shortly after the Lee Highway Association was formed. In April 1920, the association offered Dr. Johnson the position of General Director. In Dr. Johnson's view, that is when the active work of the Lee Highway Association began.

The Lee Highway Association, under his leadership, soon was backing a transcontinental highway. It would begin at the Zero Milestone in Washington, traverse the Shenandoah Valley on the Valley Pike, then continue to New Orleans, as conceived by Professor Humphreys, and end in San Diego. The association adopted the nickname "The Backbone Road of the South." Decisions were made and revised about the location of the Lee Highway during the next few years. In 1920, the Lee Highway Association agreed to follow the road from Washington to Alexandria through Fairfax Court House, Middleburg, Aldie, and Boyce to Winchester, where it would turn south on the Valley Pike. The following year, the Association decided to change the route to eliminate the "elbow" where the route dipped to Alexandria then turned northwest. The route was shifted to pass through Falls Church, Fairfax Court House, Gainesville, Warrenton, Sperryville, and Luray into the Shenandoah Valley at New Market.

Late in 1920, the route was set between Bristol, Virginia/Tennessee, and Knoxville via Kingsport, Rogersville, Tate Springs, and Rutledge. On January 20, 1921, the route to Chattanooga was finalized via Lenoir City, Loudon, Sweetwater, Athens, and Cleveland.

At this point, the Lee Highway Association made a crucial decision to turn away from Professor Humphreys' vision. The Board of Directors, meeting in Chattanooga on February 28, 1921, decided to abandon New Orleans as a stop on the Lee Highway. The adopted resolution observed that:

Whereas: serious difficulties have been encountered in the effort to locate the cross-continent route from New Orleans, including the fact that feasible routes have already been preempted by other highways,

Therefore be it Resolved: That the Executive Committee is requested to investigate the cross-continent routing with a view to a decision before organizing the line from Chattanooga south.

In July, the association met in Houston with officers of the Old Spanish Trail Association to consider linking the Lee Highway to the Old Spanish Trail (St. Augustine, Florida, to San Diego). The Old Spanish Trail Association, which had been formed in December 1915, was one of the stronger named trail associations. When it was not willing to combine with the newer association and change the name of its western portion to Lee Highway, the possibility of a merger was dropped.

Designation of the western segment would be in flux for several years. In some cases, the preferred route was not included when that State's 7-percent Federal-aid system was approved under the Federal Highway Act of 1921. With no Federal-aid funds available to improve the segment, an eligible alternative had to be found that would be eligible. The western routing would eventually traverse:

- Arkansas-Forrest City, Brinkley, Little Rock, Hot Springs, and DeQueen;

- Texas-Idabel, Hugo, Durant, Ardmore, Healdton, Loco, Walters, Frederick, Vernon, Paducah, Plainview, Muleshoe, Farwell;

- New Mexico-Elida, Roswell, Glencoe, Tularosa, Alamogordo, Newman, El Paso (Texas), Las Cruces, Deming, Lordsburg;

- Arizona-Duncan, Safford, Globe, Phoenix, Buckeye, Gila Bend, Aztec, Wellton, Yuma;

- California-El Centro, Jacumba, San Diego.

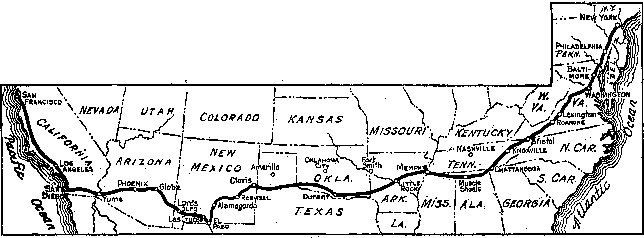

The Southwest had few routing options, so the Lee Highway Association was unable to find a separate route for its highway. In the three Southwestern States, segments of the Lee Highway followed segments of Apache Trail, Atlantic-Pacific Highway, Bankhead Highway, Broadway of America, Old Spanish Trail, and others. The association approved extensions to New York City and San Francisco, but these were over existing highways; the primary concern of the association was improving the main roadway from Washington to San Diego.

In November 1926, when AASHO adopted the U.S. numbered highway system to replace the named trails, the Lee Highway was split, east to west, among U.S. 211, U.S. 11, U.S. 72, U.S. 70, U.S. 366, and U.S. 80.

Arlington Memorial Bridge

Dr. Johnson was not satisfied with the routing of the Lee Highway across the Georgetown Bridge (Francis Scott Key Bridge) over the Potomac River and in Northern Virginia. He wanted a grand memorial entrance into Washington for his highway.

He learned of an idea that the great orator Daniel Webster, in a speech on July 4, 1851, attributed to President Andrew Jackson as a way of symbolically linking North and South:

Before us is the broad and beautiful [Potomac] river, separating two of the original thirteen States, which a late President, a man of determined purpose and inflexible will, but patriotic heart, desired to span with arches of ever-enduring granite, symbolical of the firmly established union of the North and South. That President was General Jackson.

Later Presidents supported the idea and Congress periodically funded studies. A design competition was authorized for a memorial bridge in 1899. Donald Beekman Myer, author of Bridges and the City of Washington (Commission of Fine Arts, 1974), described the result:

The competition attracted a dramatic series of colossally monumental designs all of which ran from the base of Observatory Hill near the foot of New York Avenue across the Potomac to Arlington Cemetery.

Congress was not interested in the grandiose plans.

In 1901, the Senator James McMillan of Michigan, Chairman of the Senate District Committee, sponsored a resolution that established a commission to improve the city's parks. The McMillan Committee (Daniel H. Burnham, Charles F. McKim, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and Augustus Saint-Gaudens) released its report in 1902. It included a plan for developing the National Mall and surrounding areas that largely shaped its development since then. One of the commission's proposals was to shift the District end of the proposed Memorial Bridge to the site of a proposed Lincoln Memorial rather than farther north as in earlier plans. After much debate about an appropriate commemoration, the Lincoln Memorial was authorized in 1911 at its present location. Construction began in 1914 and was completed in 1922. The Lincoln Memorial was dedicated on February 12, 1922, the anniversary of President Lincoln's birth.

In 1913, Congress authorized $25,000 for a commission to investigate a suitable design for a Memorial Bridge linking Washington with Arlington National Cemetery. In the absence of a companion appropriation, the funding could not be used.

Although the idea was dormant, it fit with Dr. Johnson's vision of a grand entrance for the Lee Highway into the city:

It was not to be a glorification of the Confederacy, but a work for the unification and development of the United States of today and tomorrow, and as such it began the movement which is spreading to be part of the plan to link together the names of Lincoln and Lee.

In 1920, Dr. Johnson conferred with Chairman Charles Moore of the Commission of Fine Arts. They agreed to work together to secure funding for a bridge on a line connecting the Lincoln Memorial with the Lee Mansion (the Custis-Lee Mansion, where General Lee and his family lived before the Civil War) in Arlington National Cemetery. In June 1920, the $25,000 authorized in 1913 was finally appropriated to establish the Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission.

With the approval of President Warren Harding, the commission adopted the idea contained in the McMillan Commission's report as suggested by Moore and Dr. Johnson. Instead of placing the bridge on a line with the main axis of the city (through the Capitol, the Washington Monument, and the Lincoln Memorial), the bridge would be placed on a southwest link between the Lincoln Memorial and the Lee Mansion.

President Calvin Coolidge transmitted the report to Congress on April 22, 1924. The report explained the Lincoln-Lee connection as one reason for the location. It also suggested "the compelling patriotic motive" of a direct broad boulevard from the Capitol through B Street extended (now called Constitution Avenue), past the Lincoln Memorial to Arlington National Cemetery. It added:

There is a third great motive in the complete plan and that is the provision of a magnificent entrance to Washington from Virginia for the Lee Highway coming across the entire country from Los Angeles, California.

The axis of Columbia Island affords an opportunity to recognize the great Lee Highway undertaking and to make it an integral part of the whole composition. This highway, which at present passes over the Georgetown Bridge into Washington by a circuitous and highly congested route, can be given a splendid direct approach over the brow of the imposing Arlington Heights, exactly on the prolongation of the axis of the Mall.

Noting that Ancient Rome had five great avenues of approach and Washington had none, the report observed that, "in this proposed terminus of the Lee Highway will be created the first and most magnificent of all possible entrances to the National Capital." It would be, the President said, the greatest symbol "of the binding together of the North and South in one indivisible Union, knowing no sectional lines."

Now the effort turned to funding. The proposal covered $15 million in projects, including the bridge ($7.5 million), construction of a plaza and water gate on the District side, extension of B Street, and the widening of 23rd Street from Washington Circle to B Street. President Coolidge believed in a limited government and was seeking to reduce expenditures. Congress was having difficulty funding even a limited bill for public works in the District of Columbia. Therefore, the Lee Highway Association, with financial help from the National Highways Association, launched a publicity campaign to drum up support for Arlington Memorial Bridge. Copies of the President's report were distributed and stories were sent to 8,200 newspapers. When Congress failed to enact the Bridge Bill for the Memorial Bridge Approach in 1924, the Lee Highway Association sent telegrams to the Nation's Governors and copies of the bill to chambers of commerce around the country soliciting their support.

Congressional action was swift in 1925. President Calvin Coolidge approved the Arlington Memorial Bridge bill on February 24, 1925. In recognition of the role of the Lee Highway Association, the President gave a pen he used to sign the bill to the association.

The New York firm of McKim, Mead and White designed the bridge, with Joseph P. Strauss (later the Chief Engineer on the Golden Gate Bridge) serving as a consultant. Construction began in 1926. The 2,138-foot bridge was completed in February 1932 at a cost of $6,650,000. Myer, the historian of Washington area bridges, has called it "Washington's most beautiful and successful bridge."

Lee Boulevard

Dr. Johnson's vision, however, was incomplete. His vision, called Lee Boulevard, was a 200-foot right-of-way from the Memorial Bridge westward 110 miles to the Shenandoah Valley. It would include a 56-foot speedway (speed limit: 35 mph) without grade crossings, a bridle path for horse traffic, two frontage roads for local traffic, landscaping, and a 60-foot zone on both sides of the road from adjacent buildings to the curb. He formed the National Boulevard Association to promote the vision and began seeking donations of right-of-way for the project.

In March 1927, Dr. Johnson resigned as General Director of the Lee Highway Association to devote time to his boulevard idea, which he expanded to the construction of a boulevard from Bar Harbor, Maine, to Miami, Florida. A 1927 brochure by the National Boulevard Association indicated he retained a direct role in the Lee Highway Association. He served as a Director and on the Executive Committee of the Lee Highway Association, as well as its Honorary President.

The office remains in Washington in his charge. He still handles the business, receives and deposits the funds and signs checks. He says he is so identified with Lee Highway that he will never cease to advance its interest.

In essence, he had relieved the association of his salary.

Still, with creation of the U.S. numbered highway system, the Lee Highway had been split among several numbers and its value diminished. Dr. Johnson was ready for new challenges.

The proposed boulevard proved controversial in Arlington County. Two location options became known as the straight-to-the-bridge route and the southern route, each with its advocates and critics. A third faction favored improving the existing Lee Highway first. The Lee Highway Association announced its preference for the southern route in July 1926. The route had been scouted by Major Carey H. Brown of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; he served as engineer for the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. He had assisted the Lee Highway Association with the approval of his superiors. Major U. S. Grant III, Director of Public Buildings and Parks, fully approved Major Brown's conclusions.

On August 1, 1926, an article in The Sunday Star explained why Major Brown had selected the southern route:

. . . it avoided the congested and narrow main streets of town, where traffic would be bottled up at frequent intervals, but also because the construction of a short road on the south side of Arlington National Cemetery would connect the Lee Boulevard with the proposed new highway to Mount Vernon. The mere widening of the present road along the cemetery, he said, would suffice to complete the link between two great highways of the future.

The southern route would not pass through any town, he said, but would be close enough for a connection by a short road or street.

Describing the route as an "engineer's dream of the future," the article described the present appearance of the southern route: "At present it is nothing but a trackless line of corn fields, berry thickets, forests and a few scattered settlements." The article also observed that throughout its length, the southern route was within a mile of the straight-to-the-bridge route.

By the date of the article, Dr. Johnson had secured donation of up to 90 percent of the land for the southern route. The remainder would have to be purchased, with the houses on the sites removed.

On July 26, 1927, Henry G. Shirley, Chairman of the Virginia State Highway Commission, held a public hearing on the proposal at the Arlington County Courthouse. Over 300 residents attended. The headline in The Evening Star reflected the continuing anger over the proposal-and the continuing sensitivities of Virginians about General Lee:

"BOOS" BROWN OUT HIGHWAY LEADER

Boulevard Hearing in Turmoil as Lincoln and Lee Are Compared

Shirley devoted the first 10 minutes of the meeting to advocates of prompt widening of the present Lee Highway. Frank Ball, speaking on behalf of Lee Highway advocates, described the road as "crooked and dangerous" and indicated he didn't care which alternative was selected for the boulevard as long as the existing road was improved first. Mrs. Ruby Lee Minar, a Washington area realtor, echoed his sentiments.

The Lee Highway, especially from Rosslyn to Falls Church is in wretched condition, and I have seen five automobiles over turned in a single week. I do not think that the members of the commission will find any opposition anywhere to the prompt widening of this arterial thoroughfare.

An hour was then allotted to advocates of the southern route. Dr. Johnson took up most of that time explaining his preference. He made it clear, however, that he agreed with the sentiment that Lee Highway should be improved first.

Next came advocates for the straight-to-the-bridge route. Mrs. Catherine M. Rogers called Lee Boulevard "the road of tomorrow" and said her preferred route was the only one that would bring people to the county. M. E. Church of Falls Church reminded the Commissioners of their "grave responsibility" and argued that the straight-to-the-bridge route was absolutely necessary. Charles T. Jesse indicated that the county's business interests were behind the straight-to-the-bridge route. George F. Harrison, a representative of Fairfax County, said his county was concerned about the choice, but favored the direct route.

Charles Moore of the Fine Arts Commission and Major Brown testified as well. They stressed that regardless of the location, it would be foolhardy to allow a difference of opinion over location to result in defeat of the idea.

One of the most "caustic assailants" of Lee Boulevard was Colonel Ashby Williams. He characterized the idea as a "wholly impractical dream." He explained:

I have no quarrel with dreamers, but dreams are usually carried on at night. But this Lee Boulevard dream is a day time dream. One that in the name of common sense should not be realized.

The hearing nearly came to an abrupt end during the testimony of Major E. W. R. Ewing, leader of the straight-to-the-bridge backers. He claimed that the Lee Boulevard adherents were commercializing the name of General Lee and that the whole proposal was simply a business proposition.

As a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans for 6 years, he felt that he spoke for the men and women of the Southland. He then set off what The Evening Star called an "hysterical demonstration" when he stated "there was no comparison between Lee and Lincoln." This slur on General Lee was intolerable to many of those in attendance:

A salvo of boos and other expressions of disapproval, accompanied by hissing, drowned out any remarks that Maj. Ewing contemplated relative to the comparison of Lee and Lincoln and for the moment it appeared that the conference would break up in wild disorder with H. G. Shirley, chairman, vainly pounding for order.

The situation worsened when Colonel. J. G. Pepper demanded that Shirley extract an apology from Major Ewing who replied "they led me to it." Scores of people had started to leave in protest of Major Ewing's comment.

The situation was saved at this moment when a women rose from the rear of the courtroom, sobbing convulsively and informing the spectators that she had two sons in the World War and that both Lee and Lincoln were equally great men.

Her comments restored order and everyone returned to their seat.

The hearing adjourned soon after this turmoil.

The comment about dreams appears to have rankled Dr. Johnson and the Lee Highway Association. On August 16, 1927, the association published a 12-page booklet called:

A "DREAMER OF DREAMS"

AND

BUILDER OF HIGHWAYS

The Eighteen-Year Record

of

Dr. S. M. Johnson

The Zero Milestone Man

The Surplus War Property for Highways Man

The Lee Highway Man

The 200-Foot Bar Harbor-Miami Boulevard Man

Author of the Slogan:

"A Paved United States in Our Day"

The pamphlet summarized Dr. Johnson's life and achievements. In response to the charge of commercialism, the pamphlet explained that Dr. Johnson's success in securing donations did not originate with real estate speculators. It was part of his "dream of a monumental highway."

As the cover letter stated, "dreams have been known to come true" and so it was for the southern route. The groundbreaking ceremony for the first section of the boulevard (Fort Myer to Fort Buffalo, now called Arlington Hall) was held on May 1, 1931, at Fort Buffalo. President Herbert Hoover was scheduled to turn the first spade of earth, but he was not able to attend; he was occupied with the official duties occasioned by the visit of the King and Queen of Siam.

Instead, Governor John Garland Pollard of Virginia officiated, with several descendants of General Lee in attendance. "This road," the Governor said, "will serve as a permanent memorial to Robert E. Lee, idol not only of the South, but of the whole world, and provide a fitting entrance to the National Capital." He also referred to a new controversy, namely objections by the Associated General Contractors of America to the State's plan to use convict labor on the project. As the Governor turned the first spade of dirt, he said, "This much of the boulevard, at least, will not be done by convict labor."

A special Lee Boulevard advertising supplement in The Washington Post on March 25 had carried an article by W. S. Hoge, Jr., of Arlington County. He expected the territory opened by Lee Boulevard to "become the Greater Washington of the future and within a reasonable time will show a development of beautiful residences, lovely homes and estates as have heretofore been but dreams." He assured readers that, "Wealth, culture, education, patriotism and happiness will all reach a higher plane via Lee boulevard."

The first section linking the two forts would be 6 miles long but it would not quite reach Arlington Memorial Bridge. Congress had failed to enact legislation that would allow construction across a corner of Fort Myer to provide the needed link. As a result, Virginia State highway maps through the late 1930's warned motorists that Lee Boulevard was not a through route to Washington. Motorists were advised to take U.S. 211 (Lee Highway) to Washington. The connection was not completed until the late 1930's and was shown for the first time on the 1939 State highway map.

Although Dr. Johnson intended the Lee Highway Association to adopt his boulevard for the route, the name remained where it was. Today, the former U.S. 211 in Northern Virginia is part of U.S. 29 (Ellicott City, Maryland, to Pensacola, Florida), and is still called Lee Highway. When Arlington Memorial Bridge opened in February 1930, it became part of a new routing of U.S. 50 (Ocean City, Maryland, to Sacramento, California) through Washington. U.S. 50 would shift again in June 1964 when the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge opened just north of Arlington Memorial Bridge. On June 29, 1965, AASHO approved a request by the District and Virginia to shift U.S. 50 onto the new bridge, with appropriate alterations in two jurisdictions.

Lee Boulevard remained part of U.S. 50. However, the connection to General Lee had been lost in the 1950's. In 1951, the American Legion Post in Arlington suggested changing the name of the boulevard to avoid the confusion of two parallel roads named after General Lee. In January 1952, State Senator Charles Fenwick introduced a bill in the General Assembly to change the name to Arlington Boulevard. Several other names had been considered. For example, the Veterans of Foreign Wars wanted to name it the Veterans of Foreign Wars Boulevard. However, the General Assembly approved Senator Fenwick's bill. Lee Boulevard, the dream of Dr. S. M. Johnson of New Mexico, became Arlington Boulevard on June 29, 1952.

The Dreamer of Dreams

The Lee Boulevard supplement of The Washington Post referred to Dr. S. M. Johnson as the "most potent, persistent, and colorful personality in the whole good roads movement in America." It added:

To him has come no material gain from his monumental visions and concrete accomplishment, but his efforts have made marketing cheaper, touring more comfortable, and the cultural unity of the Nation nearer.

He had coined the slogan, "A Paved United States in Our Day." He was known as the Apostle of Good Roads and as the Spirit Incarnate of the Lee Highway. But perhaps most appropriately, he was known as a Dreamer of Dreams-that came true.