| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |

The National Old Trails Road

Part 1: The Quest for a National Road

Section 2 of 7

The Old Trails Association of Missouri

Prof. Walter Williams Click on image for larger version |

The next issue of Southern Good Roads (January 1912) described organization of a new group, the Old Trails Association of Missouri. The organizational meeting took place on December 19, 1911, in the Commercial Club Rooms in Kansas City:

Fifty delegates representing several counties, assembled at the call of Prof. Walter Williams . . . . Mr. Williams was chosen president of the association.

Judge Lowe was a member of the Executive Committee.

The participants unanimously adopted a resolution on the purpose of the organization:

Section 1. Resolved, That it is the sense of this meeting that steps be taken toward the formation of a Transcontinental Highway Association, extending from the cities of Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, along the line of the Old Cumberland Pike, through the States of Maryland, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, to the city of St. Louis; thence west along the Old Trails Route, consisting of Boone's Lick Road and Santa Fe Trail, as near as practicable to Kansas City, Mo.; thence along the line of the Santa Fe Trail through Kansas and Colorado to Santa Fe, N.M.; and thence along the line of the Sunset Route, through New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

Section 2. Resolved, That the Governors of all the States through which the above-designated road shall run be requested to select delegates from the commercial organizations and Good Road Association along the line of said roads of their respective States to meet at Kansas City, Mo., on _____ day of , for the purpose of perfecting a National Organization.

The date was to be filled in later.

The Southern Good Roads article discussed the purpose of the new group:

The meeting was the first step toward what Mr. Williams believes will become a great transcontinental highway . . . . Many of the roads included in the transcontinental project have important branches, such as the Oregon trail, which branches from the Santa Fe trail. It is the plan of the association to place markers at such points. The markers also will be placed at all points of historic interest along the various trails.

A. L. Westgard And The Trail To Sunset

The "Sunset Route" was more correctly called the Trail to Sunset. This was an early named trail between Chicago and Los Angeles. It was established in 1910 by A. L. Westgard on behalf of his recently organized Touring Club of America.

Westgard, the premier "pathfinder" of the early automobile days, was born in Norway in 1865 and came to the United States in 1883. He began his career as a surveyor doing railroad, municipal, and land work in the Southwest. His jobs included location work for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. From 1892 to 1905, Westgard had been in charge of a corps of engineers working in all the States east of the Rocky Mountains. The corps prepared State, county, and town maps and atlases. His information helped the early bicycle tourists, but proved especially useful when the automobile age began.

During the first 2 decades of the 20th century, Westgard repeatedly traveled across country seeking good touring roads. He documented them for other motorists in maps, photographs, and motion pictures. He was a Special Agent of the Office of Public Roads at times, and worked for several motoring and road organizations beginning in 1905. In 1912, Westgard Pass in California was named after him (on today's State Route 168 in the Inyo National Forest). The title of an article about Westgard by Arthur Manchester in the June 1989 issue of Car Collector and Car Classics conveys a sense of his last 15 years: "A Marco Polo of The Motor Age." While on the dedication tour for the National Park-to-Park Highway in 1920, he became ill while passing through Spokane, Washington, traveled by train to Oakland, California, for surgery, but died on April 3, 1921.

A 1911 AAA booklet of strip maps of the "Trail to Sunset Transcontinental Automobile Route" shows the route. According to the booklet, "The route for the Trail to Sunset has been carefully and deliberately chosen from a strictly touring standpoint, offering the most varied and numerous points of historic interest." Like future U.S. 66, the Trail to Sunset began at Jackson and Michigan Boulevards in Chicago. However, the Trail to Sunset continued west out of the city to La Grange, unlike U.S. 66, which turned southwest at Ogden Avenue. The trail crossed Iowa on the River-to-River Road (future U.S. 6), and joined the future National Old Trails Road in Lyons, Kansas. The two routes separated at McCartys, New Mexico, with the Trail to Sunset going through Phoenix before breaking into two branches, via Yuma, Arizona, and Blythe, California, on the way to Los Angeles.

The cover noted that the booklet was based on Westgard's notes. Westgard compiled the notes for the strip maps, including information on road conditions. For example, he noted that asphalt pavement ended at Madison Street in Chicago. He found graded dirt roads in Kansas. In New Mexico, he encountered such features as a "Ford (Sandy Bottom)" and "Heavy Sand." He finally encountered a "Fine macadam Boulevard," at Redlands, California, and followed macadam roads, "Well Signposted," all the way into Los Angeles. The Trail to Sunset ended at the intersection of Main and Spring Street in Los Angeles.

Westgard being primarily a pathfinder, the Trail to Sunset did not follow the later pattern for named trails. It did not have a backing organization to promote its improvement and use. As a result, it soon lost its identity as an interstate trail. In October 1917, The Road-Maker printed a AAA summary of national tourist roads, including the Trail to Sunset, but noted:

. . . starts at Chicago and runs to Los Angeles along the Santa Fe trail and across New Mexico and Arizona to Southern California, thence north to San Francisco . . . . The original line of the Trail to Sunset was through Albuquerque, Globe, Phoenix and Yuma, the way it is largely traveled today; but more lately there has been developed a new and shorter connection from Albuquerque through Holbrook, Flagstaff, Williams, Needles and San Bernardino to Los Angeles . . . . This route . . . will probably divide future traffic about evenly with the older way through Phoenix and Yuma.

The "new and shorter connection" was better known by 1917 as the National Old Trails Road and became U.S. 66 in 1926.

The Trail to Sunset inspired a novel that was published in March 1912 by Moffat, Yard and Company. On the Trail to Sunset was written by Special Agent Thomas W. Wilby and his wife Agnes and illustrated with photos from their transcontinental trips . In it, an idealistic journalist accompanied his globetrotting Uncle John Eastcott, John's wife Nell, and a chauffeur on a trailblazing trip along the Trail to Sunset. A newspaper in New York heralded the trip:

WELL-KNOWN GLOBE-TROTTER TO CONQUER THE WEST!

JOHN EASTCOTT TO BLAZE A TRAIL ACROSS BY AUTOMOBILE

AND END THE MONOPOLY OF THE RAILROAD!

The novel included a romantic interest, a revolutionary movement to remove the Southwest from American control, sabotage of the transcontinental journey, an Indian attack, and a car chase along rough northeastern New Mexico roads at speeds exceeding 20 miles per hour. In the end, the young man wins his true love, the Southwest remains part of the United States, and the transcontinental pathfinding trip is a success.

In RoadFrames: The American Highway Narrative (University of Nebraska Press, 1997), Kris Lackey critiqued On the Trail to Sunset. He described it as "a preposterous throwback, and its reactionary colonialism, depicting Hispanics as wild-eyed fanatics and Native Americans as childish, defeated savages, lacks the revisionist romanticism of later nonfiction narratives." Lackey concluded by explaining the point of the novel, as he saw it, namely that a cultivated Easterner can "muster virility enough" to defeat his native rivals, "thus insuring the right and proper march of Anglo civilization into the recesses of the continent." In short, it wasn't a very good novel.

The Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association

The day after the Old Trails Association of Missouri was formed, the Tri-State Road Convention was held in Phoenix on December 20-21, 1911. The organization was based in Arizona, California, and New Mexico, with the Governors of each State appointing the delegates. As in Missouri, officials in the Southwest wanted to influence what they anticipated would be Federal decisions on transcontinental highway routings. John S. Mitchell of Los Angeles was elected president, with J. S. Cornwell, also of Los Angeles, the treasurer. The secretary was George Purdy Bullard of Phoenix.

The new organization had to address efforts by San Diego boosters who had been fighting for years regarding highway routing between Phoenix and Los Angeles. Early automobile traffic between the two cities went via San Diego and Yuma across the difficult roads of the Imperial Valley. San Diego interests, fearing their city would become a backwater if transcontinental traffic went directly from Yuma to Los Angeles, had identified a routing that would become U.S. 80 when that route was designated in the 1920's (I-8 roughly follows the route today). Los Angeles had adopted a route following in part the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad from Yuma to San Bernardino by way of the Salton Sea. Nevertheless, San Diego advocates claimed their route was a faster way to Los Angeles, in part because it cut off 100 miles of desert travel.

This longstanding dispute would emerge during the organizing convention of the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association. According to an account of the convention in the January 1912 issue of Touring Topics:

In the ensuing business session on the day following [December 21] the principal matter brought up for settlement was the selection of the route which the highway should follow through the state of California. The delegates representing San Diego and the southern portion of the Imperial Valley were insistent that the association should endorse a route by way of Yuma to El Centro, thence over the Devil's Canyon to San Diego and up the coast to Los Angeles, while the northern men united with the Los Angeles and upper Imperial Valley delegates in espousing a route through the Imperial Valley to Beaumont, Banning and thence into Los Angeles.

During a meeting before the convention, the California delegation had unanimously selected the Beaumont-Banning route, which left San Diego out, as the favored course. San Diego delegates had declined to attend the caucus:

On the floor of the convention, when the matter of the two routes came up, some rather acrimonious debate was indulged in, but President Mitchell ruled that the speakers for the San Diego delegation were out of order and a resolution embodying the Beaumont-Banning route was adopted for transmission to the federal authorities as the official action of the association.

According to the adopted resolution, the route recommended to the Federal Government ran "westerly from Yuma, along and near the Southern Pacific Railway, to a point about 4 and one-half miles west of Mammoth station, thence southwesterly to Brawley, thence northwesterly along the south and west side of the Salton Sea to Mecca, thence along the line of the Southern Pacific tracks to Beaumont, Redlands Junction, Colton and thence along the shortest route to Los Angeles." The resolution indicated that the route had been selected because the association believed the route presented "the fewest geographical and physical obstacles," passed "through as much settled territory as possible" and was "within striking distance" of a transcontinental railroad.

An article in the January 13, 1912, issue of Good Roads described the western division of the route:

[It] begins at Raton, N.M., running from there to Las Vegas, through Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Carthage, San Antonio, Cocorro [Socorro] and Magdalena, N.M., Solomonville, Globe, Roosevelt, Phoenix and Yuma, Ariz., and Mammoth, Cal., west to Mecca, via Beaumont, through Redlands Junction and Colton to Los Angeles.

That was essentially the route of the Trail to Sunset.

By April 1912, Touring Traffic could report progress in improving the new route:

Three months ago there was no direct connecting route between Los Angeles and Yuma, a city just over the Colorado River in Arizona. The automobilist of Los Angeles or vicinity who wished to go to Yuma was compelled to travel down the coast to San Diego and thence over the difficult roads through the lower part of the Imperial Valley and on to his destination. Today he can travel over a direct route between the two cities and he will find the roads ranging from fair to excellent for the entire three hundred and two miles.

Extensive work had been completed:

[The Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association] has secured a fourteen mile right of way between Ontario and Colton that provides a direct and excellent route between these two cities. It has overcome the extremely difficult and often impassable stretch of road at Whitewater Point by constructing four miles of new roadway along higher ground that provides a good rock foundation and is beyond the reach of water even during the rainy season. A new road has been built between Mecca and Brawley, a distance of sixty-four miles, and this highway is in very good condition. The road between these two points was formerly a sandy trail that, for the most part, could be negotiated only by the higher powered cars. Between Brawley and Yuma a fairly good road has been provided by way of Mammoth and Ogelby. This particular portion of the proposed ocean-to-ocean highway presents road engineering problems of some difficulty and to provide a first class highway between the two points will entail a considerable cost.

Mitchell and other leaders of the new association began working with other associations interested in being part of the route that they hoped the Federal Government would build. As Touring Topics put it in April 1912, "President Mitchell and Secretary Conwell have not been confined to the extreme west but they have been successful in inoculating the Eastern states with the virus of their enthusiasm." One of the groups that Mitchell worked with was based in Missouri.

The First National Old Trails Road Convention

On April 17 and 18, 1912, Professor Williams presided over the National Old Trails Road Convention, held in the Commercial Club Rooms in Kansas City. The Committee on Credentials certified delegates from Ohio, Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. Maryland, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and California did not send delegates.

Mrs. Hunter M. Merriwether, the Missouri State Vice Regent for the D.A.R. and a member of the Missouri Good Roads Committee, addressed one of the main problems facing the convention, namely routing. No one questioned the eastern portion of the new named trail. It would follow the Cumberland Road to its terminus in Vandalia, Illinois, continue on to St. Louis and Kansas City via the Missouri Cross-State Highway. West of Kansas City, however, the best location for the trail was in dispute.

Citing Shakespeare's claim that "a rose by any other name would smell as sweet," Mrs. Merriwether commented:

In your case, your name is your fortune. The "Old Trails Road" tells its own story . . . . The men of Missouri saw the need of a State Highway, and the Daughters of the American Revolution joined hands with them and helped them to decide the proper place to put the road.

Why not build the National Ocean-to-Ocean Highway along the Old Trail's Road as Missouri has built her link?

Each of the trail States should insist that the Trail Road be adopted as their State Highway.

She emphasized the importance of designating the route along the historic trails chosen by the D. A. R. instead of the alternatives under consideration. A good road that was not also historic would spoil the significance of the name:

Hold to your name and build that National Old Trail's Road. We, Daughters of the American Revolution, do not come before you to plead for it, because the section through which it passes is a great commercial one, but because it was the pathway of our forefathers, who took civilization from the tidewaters of the Atlantic to the golden sands of the Pacific . . . .

When we gather our children about our knees, we do not tell them of the great captains of industry, of the leaders of finance. We tell them of Washington and Lee; of Daniel Boone, who led the pioneers along the "Wilderness Road," across the Mississippi; of Meriweather [sic] Lewis, and William Clark; Whiteman and Spaulding, of the Oregon Trail; of Colonel Alexander Doniphan, General Stephen Kearny; of Fremont and Thomas H. Benton, the Lion Hearted . . . .

Men of brain and brawn, fling away personalities in this Old Trail's Road building. Root from your hearts the miasma of commercialism, which, in its fever and fury, blinds your eyes to the upper and higher aim, that of united hearts and hands across this great country of ours, to build a National Monument that will ever be pointed out as the Old Trail's Road, which has been designated as "The Road of Living Hearts," over which marched the civilization, opportunity, religion, development, and progress of our grand America.

Routing Disputes: The New and Old Santa Fe Trail

One of the major routing battles was between rival forces backing the New Santa Fe Trail and the Old Santa Fe Trail in Kansas. The New Santa Fe Trail was the first named trail in Kansas. Interests in Hutchinson began the trail by calling a convention in January 1910 to select a route between Newton and the Colorado State line, via Hutchinson, Kinsley, Dodge City, Cimarron, Garden City, Hartland, and Syracuse. The 300 delegates who attended the convention established a temporary organization, chose the name for their route (after rejecting the Valley Speedway), and urged eastern Kansas good roads boosters to extend the route to the east. In May 1910, a conference in Emporia established the eastern routing. In October, Westgard included the New Santa Fe Trail in his Trail to Sunset.

A competing association formed in November 1911 at Herington. This group mapped the Old Santa Fe Trail, as close as possible to the historic route, given section line land division and modern development. West of Lyons to Santa Fe, the two routes were identical.

The competition between the two Kansas groups was intense, primarily because they were competing for the business that would follow the main transcontinental artery. Of course, the D. A. R. interests supported the Old Santa Fe Trail, because of its historic importance, for inclusion in the National Old Trails Road.

On April 12, 1912, Ralph Faxon, President of the New Santa Fe Trail Association of Kansas, addressed the convention in support of designating his line. Just before Faxon spoke, Professor Williams had acknowledged the arrival of Chester Lawrence. He was on a pathfinding transcontinental trip from New York to Los Angeles under the sponsorship of the William Randolph Hearst newspaper organization and the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association:

THE CHAIRMAN: I want to step aside from the regular program just at this moment to introduce to you the first man who will follow the National Old Trails Road entirely across the continent, Mr. Chester Lawrence. (Applause).

MR. LAWRENCE: We have been a long time coming, gentlemen, but we are here.

THE CHAIRMAN: He will say something to us a little later, because just at present he has come up out of tribulation-I mean Kansas. He has to catch his breath. (Laughter).

Faxon picked up on the theme at the start of his speech:

A little while ago . . . my friend, the president of this conference, suggested that Mr. Lawrence had recently come down out of tribulation, meaning Kansas, and the thought occurred to me, and I think my Kansas friends will agree with me perfectly, that possibly he did come out of tribulation, but he didn't help matters much by coming into "misery," (Laughter and applause).

After discussing the good roads movement in Kansas, he turned to his main concern:

I pause for a moment to pay my respects to these Daughters of the American Revolution-and many who are not here I know will join me-in paying respect to them for the work they have done. But I say, stripping it of its sentiment, there must be organization and practical construction. There must be practical work and must be men's work along with it.

He said that his association was a pioneer of the good roads movement in Kansas and listed some of the men who helped create the New Santa Fe Trail:

It is men like that who have done the road work in connection with the New Santa Fe Trail; and when anybody tells you that mere sentiment should govern more than honest, sincere efforts of a band of men covering a period of years and extending as it has back into a time in the past that makes it the pioneer of all the roads of the West, then I want to tell you it is time to pause and think a minute, and to pay tribute to the men who have gone to the front and done the actual work that has been done by the New Santa Fe Trail and by its organization. Mr. Williams knows it. Mr. Wilby knows it. Mr. Westgard knows it. The American Automobile Association knows it and Chester Lawrence knows it; the office of public roads of the United States, Department of Agriculture knows it . . . .

Faxon concluded, "I thank my stars that it has been recognized from the government down to the humblest traveler as one of the most significant things in Good Roads in all the West."

Now, George P. Morehouse, speaking on behalf of the Old Santa Fe Trail Association, referred to Lawrence:

Those two organizations [the New and Old Santa Fe Trails] should receive encouragement. But when you hold a national Old Trails convention to induce the United States Government and other interests to improve a great ocean-to-ocean highway across this country along this historic line, it is no wonder that the action of your convention was so unanimous in selecting by resolution, the route of the Old Santa Fe Trail . . . rather than the new trail (applause)-rather than that new Santa Fe Trail of modern times which my friend Faxon represents and which this distinguished automobilist has partially come over, and would have been here many hours before if he had only taken the old natural route. The trouble with Mr. Lawrence has been that he did not follow that old natural route that kept away from the boggy, the sandy and the gumbo bottoms of the cottonwood and other regions he has been obliged to come through. (Applause.)

. . . But when it is stated here that the Old Santa Fe Trail is simply a sentiment, I take issue with that; and, looking along its historic value, I want to say something in regard to why sentiment is even stronger often than commerce. Sentiment is the reason that the Daughters of the American Revolution . . . have always worked to have the national highway follow along the Old Trails line. Sentiment is the reason that the national organization of the D.A.R. in Washington yesterday has sanctioned and asked that the Old Trails line should be used. (Great applause.) Sentiment has accomplished more in this country, often even drenching our country in blood rather than to cut it up, when possibly a little commercial finesse would have prevented it. And sentiment is what will ultimately get the United States Government to make vast appropriations for roads from one end of our country to the other, more than even the strength and political sagacity of commercial centers. (Applause.)

That afternoon, during debate on the association's constitution, Faxon tried to convince the convention to postpone adoption of the "Old" line. Noting that the adopted resolution only "recommends" the Old Santa Fe Trail "as nearly as practicable," he said:

I should be absolutely failing in the decency and respect that we all owe to an organization that has promoted more than one good thing, if I did not preface the few words I am going to say with a tribute which comes from my heart towards the Daughters of the American Revolution.

[But] I stand on those words, "as near as practicable," and Mr. Miller [J. M. Miller, representing the Old Santa Fe Trail Association] ought to stand on them, and the rest of my good friends ought to stand on them; and then we can take this thing home where it belongs and fight it out and settle it for all time, and the winner will have the support of the vanquished and we shall all be together in this movement.

Faxon also complained that the resolution endorsing the Old Santa Fe Trail had not been properly introduced to the convention by the Committee on Resolutions.

. . . why try to run anything over us which did not come through the channel of the Committee on Resolutions in the ordinary and orderly manner?

Mr. Miller replied:

For what purpose are we here? We are here for the purpose of determining the national highway that shall connect the two oceans, if we have any purpose at all; and my friend Faxon knows it as well as anybody on earth, and he knows that the only thing we can do is to appeal to the people here-not to run the bandwagon over them. There is no disposition in this magnificent audience to run the bandwagon over anybody, but above and beyond any other organization on earth, this organization will never run the bandwagon over the Daughters of the American Revolution, after their grand work in this cause. (Applause and cheers). Daughters of the American Revolution, I cannot give you my heart. It is not mine to give. I would first have to interview the lovely little woman out at Council Grove; but you have my voice and my hand in every good work and my help in the good work you are undertaking. You may accept the hearts of these gentlemen who belong to the New Santa Fe Trail, if you will, and their wishes in your good work; but it will not help you very much, in my judgment, unless you have their determined effort to carry out what you want done.

When the issue was resolved in favor of the Old Santa Fe Trail, Professor Williams joked:

I wish to call attention to the meeting tonight before I get further on, so I will not forget it. I understand that Mr. C. R. McLain of Kansas City will present an illustrated lecture at the New Casino--and I hope those of us now who favor the "Old" will not stay away because it is the "New" Casino, if that is the name of it--on road building.

Routing Disputes: The Ocean-to-Ocean Highway

The other main controversy over routing concerned the Southwest, where few good roads existed. Colonel Dell M. Potter, of Clifton, Arizona, addressed the convention on the second day. (He noted that his title of "Colonel" resulted from his having been paymaster of the State's National Guard.) Potter explained how the organization he represented, the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association of Redlands, California, came about:

Four years ago I went to the Chamber of Commerce in Los Angeles and asked if they would not assist us in boosting the National Highway from the Pacific to the Atlantic . . . . And what has the state of California done? It has bonded itself for eighteen million dollars for the purpose of building what? Building automobile roads--not transcontinental roads, not roads for the benefit of you and me, but roads that will benefit California and allow or permit California to have [automobiles] shipped by train from across the United States to its eastern line and tour through from there. We want to take some of this [touring] money from them before they get to California. I want to tell you if you get to California and ever get away with a cent you do more than the Potter tribe ever has. (Laughter) . . . .

After four years of hard fighting in Arizona, we believed that we could settle our difficulties as to where our part of the National Highway should cross the state, and . . . at a meeting called on the 20th of last December, at which twenty-eight delegates from the State of California and twenty-eight from New Mexico and twenty-eight from Arizona met together for the purpose of organizing some kind of a transcontinental or national highway. We found, to our sorrow, that the fight had been making us only trouble. We found more Arizonians there interested in taking that road across the northern part of the state than we knew there was in Arizona. They all believed they were entitled to have it, but we finally eliminated and finally settled our difficulties. We settled our difficulties in the state of California, and so did the state of New Mexico; and so far as the National Highway across the state of Arizona and the southern part of California and the state of New Mexico is concerned, that is absolutely settled. We have no more fight. But I can tell you the Lord could be proud of some of the fighters they have got in the northern part of the state, and the devil could afford to give half his kingdom for some of those fighters up there . . . .

I want to say that four years ago we advocated the building of this transcontinental highway following the Santa Fe Trail, and we have fought this thing out up to the 20th of last December, and then agreed that this should be the line of road from ocean to ocean, and the first one built by the United States government. We say that we are in a position to show you people from Missouri, those that have that [transcontinental] disease, and we must show you and we are ready to show you. We are not babies in this particular, if we are the "Baby State" in the Union. We began this thing, and we have been fighting for Colorado and Kansas and Missouri and Illinois and Indiana and Ohio and New York and New Jersey and Pennsylvania to have them put on the map, long before this association was formed. We are not asking for any credit for that, but we saw the writing on the wall and said, "We have got to get busy and have got to bind these various states together."

Colonel Potter also explained how the association was named:

I want to say, with reference to the name of that association, it was finally suggested as the Southwestern Transcontinental Highway Association. I said, "Not in a thousand years. We will make it something broader than that. It must be either the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association or the Transcontinental Highway Association." You could not inject into that organization or any other such organization as that anything as narrow as any particular section of the country. We finally agreed that the name of the association should be the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association.

According to the proceedings of the National Old Trails Road convention, no one argued against Potter's position.

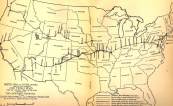

US map showing proposed location of National Old Trails Road Click on image for larger version |

The convention adopted a route along the Cumberland Road, the Cross-State Highway through Missouri, the "Old Santa Fe Trail" to Santa Fe and "from Santa Fe west on the most historic and scenic route to the Pacific Coast." Possibly, debate within the Committee on Constitution and By-laws, not reported in the proceedings, blocked adoption of the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway's route through New Mexico, Arizona, and California during the first convention. The Oregon Trail branch, as shown on Miss Gentry's map, was not included; to judge from the proceedings, this branch was never seriously considered part of the route.

On another matter, Colonel Potter offered a suggestion:

Mr. Chairman, I move you that it is the sense of this Association, born today, that we affiliate with the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association, with one and the same purpose in view; that we affiliate with them and work with them first, last and all the time to the end that this one first transcontinental highway from ocean to ocean be completed.

The motion was carried. In addition, the convention resolved:

That the thanks of this convention is extended to the Daughters of the American Revolution, who, by their energy and patriotism, have so permanently marked the "Old Santa Fe Trail" by lasting monuments in several States, and that the route of this historic old highway will be forever preserved to posterity.