| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |

The National Old Trails Road

Part 1: The Quest for a National Road

Section 4 of 7

Buffalo Bill

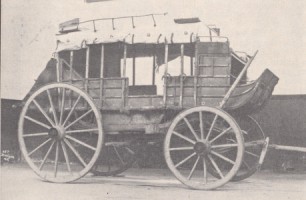

Stagecoach donated to Old Trails Road Committee of the D.A.R. by Buffalo Bill Cody Click on image for larger version |

William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody had been a member of the Advisory Committee to the Missouri Good Roads Committee, but in October 1912 he took another step in support of the cause. Miss Gentry announced that Buffalo Bill had donated a stagecoach to the Old Trails Road Committee of the D.A.R. According to an account by Miss Gentry in the February 1913 issue of Better Roads, the gift came about by accident:

Col. Cody was visiting his old friend, Col. Daniel B. Dyer, whose southern mansion down on the Independence road is locally famous. Col. Dyer's niece, Miss Green, invited a number of guests to meet Col. Cody.

We sat on the wide gallery under the August moon and listened to Col. Cody tell thrilling tales of his life on the plains. Col. Cody is a raconteur of brilliant ability and we sat fascinated for hours. His last story was of the first exhibition of his Wild West Show in London, when the Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward) and four European monarchs, then on a visit to the court of St. James, commanded a ride in the Deadwood Coach, with Col. Cody as the driver[. T]he Prince introduced "Buffalo Bill" to his guests, put them inside the coach and as he took his seat on the box remarked, "You probably have never held four kings before." Col. Cody with the same nonchalance that made him famous as Government scout, and pony express rider and plainsman, drawled back, "Better than that, I held four kings and the joker."

This repartee amused the prince and he thereupon booked passage for the next afternoon's performance, for the Princess of Wales and the royal children. "Buffalo Bill" became lionized; his Deadwood coach, and Wild West Show became the fashion; requests poured in from the English fashionables for rides round the show ring, with the Indian attack and company rescue and all the thrillers thrown in.

Col. Cody rested on his laurels and would not drive for any one under royalty. Passage was booked up for every night of the show's long run, but the regular stage-driver sat on the box.

Col. Cody finished his tale by inviting Miss Green and me to ride in the Deadwood Coach at the following afternoon performance. We laughingly accepted with the provision that he present the coach to the D.A.R. Old Trails Road Committee.

Col. Cody took the banter seriously and said he would present the committee with a Deadwood coach, but the Deadwood coach was promised to the Smithsonian Institute. Through the courtesy of the Burlington Railroad and the interest of its officers in the Oregon Trail, which is part of the Old Trails Road, the coach was transported from Cody, Wyoming, to Kansas City, where it is on public exhibition at the Swope Park Zoo.

Cody wrote to Miss Gentry on October 26, 1912, to inform her of the history of the stage coach.

I think the one you have was built by the Abbott Downing Company at Concord, New Hampshire, in 1863, was shipped around the Horn to California and was used on the California stage lines; finally worked its way East on the Ben Holliday overland stage line to Old Fort Laramie; then used by Cheyenne and Deadwood Black Hills line.

He added, "It has been baptized in blood many times."

Miss Gentry concluded her account with a comment about the Old Trails Road:

Red, white, and blue bands on the telegraph poles mark the "D.A.R. road" across Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas. Soon, tourists will be able to "Follow the Flag" across the continent. A D.A.R. motor-party will rendezvous at Westport, Missouri, in 1915, and form a motor caravan to journey to the Panama-Pacific Exposition where they hope to dedicate the Old Trails Road as the National Highway.

Location of the National Old Trails Road Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, December 1912

On December 12, 1912, Judge Lowe addressed the Indiana State Better Roads Convention. By then, the National Old Trails Road Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association had settled, tentatively, on its route in the Southwest. The association, based in 222 Midland Building in Kansas City, published the speech as a brochure in support of the construction and maintenance of the highway by the Federal Government.

At the time, the National Old Trails Road included six historic trails. The first was Braddock's Road in Maryland. In 1755, during the French and Indian War, Major General Edward Braddock led British and Colonial troops, including Colonel George Washington, from Alexandria, Virginia, to take Fort Duquesne (at the future site of Pittsburgh) from the French . Leaving Alexandria, Braddock's army marched to Rock Creek in what is now Washington, D.C., then north on the established Georgetown-Frederick Road. Leaving Frederick, the army marched to Boonsboro. This portion of the route was incorporated into the National Old Trails Road Ocean-to-Ocean Highway. West of Boonsboro, however, Braddock's march dipped to the south, going through what was then Virginia before turning north to Cumberland, Maryland. From Cumberland, Braddock and his troops partly followed a path that had been blazed in 1751 by Colonel Thomas Cresap and Christopher Gist, with the help of a Delaware Indian named Nemacolin, on behalf of the Ohio Company. Washington had widened the path to 6 feet in 1754 on a campaign that ended in defeat at his makeshift Fort Necessity, about 15 miles north of the Pennsylvania line. Braddock, Washington, and their troops widened the path partway to Fort Duquesne. Before reaching their goal, however, they were defeated in a surprise attack and Braddock killed. The National Old Trails Road Ocean-to-Ocean Highway roughly followed Washington's and Braddock's route west of Cumberland.

From Cumberland to St. Louis, the National Old Trails Road Ocean-to-Ocean Highway followed t he Cumberland Road (also called the National Road), the country's first great national road. After the Revolutionary War, Washington saw the need for such a road to link the States along the East Coast and the territories west of the Allegheny Mountains. He feared that without better transportation, the western territories would be drawn to the English in the north or Spanish interests in the south. President Thomas Jefferson signed the legislation authorizing the National Road on March 29, 1806, to serve as a portage linking the Potomac and Ohio Rivers. It went from Cumberland, Maryland (the head of navigation on the Potomac River in those days) to the Ohio River at Wheeling. The National Road to Wheeling, built of crushed stone and completed in 1818, soon became the route of commerce that helped bind the union of settled East Coast communities and the pioneer communities in the territories.

In 1820, funds were approved to extend the road to a point on the Mississippi River between St. Louis and the mouth of the Illinois River. The western terminus was changed to Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1825. By 1833, the National Road was completed as far as Columbus, Ohio, and it would reach Springfield, Ohio, but beyond that point, the road was simply laid out to Vandalia (then the capital of Illinois). A dispute over location west of Vandalia was not resolved before the coming of the railroad rendered the road obsolete. The Federal Government began turning the National Road over to the States. West of the Ohio River, the States operated the old road as a turnpike, known as the National Pike.

The third historic segment was Boon's Lick Road in Missouri. In 1806, two of Daniel Boone's sons, Nathaniel and Daniel, traveled from St. Louis to salt springs on the Missouri River, a distance of about 135 miles. They established a successful business transporting salt to St. Louis . The road they traveled on, extended to what is now known as Old Franklin, was called Boon's Lick Trail (without the "e"). Although it was more a trace than a highway, it proved to be the trail of migration across the State.

The Santa Fe Trail from Missouri to Santa Fe was the fourth historic segment. The Santa Fe Trail was established in 1821, when Mexico gained its independence from Spain. Until then, Spain had banned foreign trade. In September, William Becknell left Old Franklin for Santa Fe with a pack train of trade goods. His trip to Santa Fe was so successful, that it inspired hundreds of other traders to follow his path. He also established the Cimarron Cut-Off.

The brochure listed the fifth historic segment, Doniphan's Road from Santa Fe to Rincon, New Mexico, as a "Tentative" location. During the Mexican War in 1848, Colonel Alexander W. Doniphan led an army of Missouri Mounted Volunteers south along El Camino Real to Chihuahua, where he defeated his Mexican opponents. El Camino Real was part of a network of roads built by the Spanish to connect Mexico City with Spanish territory in what became the United States. The branch from Mexico City to Santa Fe (founded 1609) developed during the 16th Century. It was the first of the three branches, the other two ending in St. Augustine, Florida, and Sonoma, California. The central branch, roughly followed today by U.S. 25/1-25, is sometimes called "the oldest road in America."

Kearny's Road to California (also listed as "Tentative"): The map in this brochure showed Kearny's supposed route following El Camino Real to El Paso, Texas, before turning west. As noted earlier, Kearny turned west with Lt. Kit Carson at Socorro.

Judge Lowe, in his speech, explained:

Other roads ought to be built. All National highways, by the General Government, but we have selected, and are concentrating our efforts on this as being entitled to first consideration.

The brochure also reprinted Judge Lowe's letter to Chairman Bourne of the Joint Congressional Committee on Federal Aid in the Construction of Post Roads. Judge Lowe's view of Federal-aid was clear:

There is much confusion of thought on the road question. So-called "Federal Aid"-a misleading phrase-is responsible for much of this confusion. It ought to find no place in road literature. The States need no "Aid" from the General Government or from any other source in building their own highways. No such phrase occurs in the Act establishing the National or Cumberland Road. No such expression anywhere occurs in the history of that highway. The Government did not "Aid" the States through which it ran and neither did the States "Aid" the Government. It was declared to be a National Highway and was built and maintained by the Government exclusively. It was as much under the supervision and control of the Government as if it had been a navigable river . . . .

Let Congress exercise its undoubted authority, either directly, or through a Commission or Bureau of Highways, to decide what roads are National, and take over such roads for improvement and maintenance by the Government.

He thought Congress should decide which national roads would be built first; any of those under consideration would cost about $20 million. The States and counties could then build a system of lateral or local roads intersecting the national roads:

This system if adopted, will not require the levying of a single dollar of additional National taxation, will build at least one transcontinental highway annually, will add millions of dollars to property values, and thus increase enormously the Federal revenues, and add to the sum of human welfare and well being beyond any other single activity of government endeavor.

No purpose to which the revenues can be applied will accomplish so much-will do so much good to so many people-will in a few years' time, place this country, in material prosperity, far above any country in the old world. And when this is done we will only marvel at our long delay, and wonder why we postponed the accomplishment of the greatest purpose ever conceived when it was the easiest and most obvious thing to do.

Southwest Rival

While the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association promoted its route as the Southwest link in the expected national transcontinental highway, residents along a rival for the southwest connection began to promote their own claim.

The route was to the north along the tracks of the Santa Fe Railroad from Kingman, Arizona, via Needles, Barstow, and Victorville, California, to Los Angeles. An article in The Needles Eye of June 22, 1912, reported improvements along the route in California. From Needles to Barstow, the road was partially macadamized. Signs along the route helped motorists find the road. A new road had been built from Barstow to Victorville. A skilled motorist with "a good machine," the article explained, will have little trouble on the road, but a motorist who is familiar only with hard roads "must not be disappointed if he is compelled to ask the assistance of the faithful horse to extricate him from some of the deep sand beds or pull him up some of the steep grades."

In November, O. K. Parker of the Automobile Club of Southern California was traveling the area in a Franklin car mapping the roads for auto guides and placing signs along the best route. The Needles Eye reported in its November 22 issue that he had been in the city "visiting with auto enthusiasts." The newspaper reported that, "Mr. Parker states that the roads from San Bernardino here are far better than those by way of the southern route which has been used in the recent road races and which is getting prominence now because of its probable selection as the location of the Ocean-to-Ocean highway."

The article explained that for practical reasons, improving the roads was important for the future of the area:

The Ocean-to-Ocean highway means plenty of people passing through the country and with increasing numbers each year. Beside the addition they will give to local business directly, there will be the constant advertising of the country.

The issue of November 30, 1912, reported on a meeting of the Mohave County Good Road Boosters in Needles to promote a route from Los Angeles via Barstow, Needles, Kingman, Seligman, Ash Fork, Williams, Flagstaff, Winslow, Holbrook, Springerville, and St. Johns, with connections to Prescott, Phoenix, Bisbee and other points "whereby the great auto traffic of the near future as well as the annual road races will pass through these various places." The boosters were convinced of the merit of their route:

It is generally conceded that this Northern route has many advantages over the southern roads and accommodations and is through a country of great scenic beauty. The scenery in the Arizona mountains cannot be excelled anywhere and the Grand Canyon stands alone as the most gigantic work of nature.

The accommodations were the restaurants, hotels, and lunchrooms operated by the Fred Harvey Company since 1870 along the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway (Santa Fe Railroad) throughout the southwest, and some other States, including Kansas.

Participants discussed improvements underway and planned, while deciding on a course of action:

Correspondence will be entered into at once with the other organizations and prospective organizations. Activity will be urged all along the line. It is probable that at least seven or eight machines from Needles accompanied with two or three from Kingman and some from perhaps further east will move in solid formation west from Needles to San Bernardino and obtain the co-operation of every person they will meet. At the same time autos from Kingman, augmented with several from here, will travel east through Arizona enthusing the people of that state.

The boosters agreed with other boosters around the country that the goal was to have the road in shape by 1915 in time to carry traffic bound for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco and the companion Panama-California Exposition in San Diego:

It is estimated that there will be fifty thousand cars drive across the country in 1915. Some have estimated double this amount. If the best road is along the Santa Fe they will all come this way.

Needles, the article concluded, would become the gateway to southern California. "BOOST NOW AND KEEP ON BOOSTING, else join the discard."

By early December, the newspaper could report that the route from Needles to Los Angeles would be included in the road maps of the Automobile Club of Southern California and the Arizona Good Roads Association.

On December 13, 1912, the Needles Good Roads Association met with O. K. Parker, who had reached the city in his Franklin with his wife. They agreed to call the northern road the Santa Fe-Grand Canyon-Needles route. As explained in the Eye the next day:

The Grand Canyon attracts the traveler because of its widely known grandeur. Santa Fe designates the many accommodations to be had along the line as well as commemorates the old Santa Fe trail, while Needles means the gateway both east and west for this great highway over which the motorist will travel in increasing numbers as the years pass.

The newspaper reprinted an article from Our Mineral Wealth of Kingman that claimed, "The southern route booster is working entirely on long stretches of sand and hot air for his favored route for the National Highway." The article warned readers:

They are as numerous as the leaves of a forest down there and they may pull the winding way through their jungles unless the northern few [who] backed the only practical route get into the fight in earnest and show these Wise Men of the East.

The cause was boosted a few days later when Parker happened to be in Kingman the same day as O. D. Hamilton and Barry Locke, his counterparts from the Arizona Good Roads Association. Parker was traveling east promoting a Los Angeles-Phoenix road race through Needles, while Hamilton and Locke were headed west to continue mapping the route. The December 21 edition of The Needles Eye described the meeting:

The two charting parties were entertained at Kingman and a very enthusiastic meeting held and everything of the plans talked [about] here again gone over there and Needles greatly appreciates that it has the active co-operation of the people of Mohave County . . . . As our people already know that Mr. Parker is mapping the road for publication in the road book of California so are Messrs. Locke & Hamilton mapping the road from the Colorado River to Los Angeles for the purpose of publication in the new road book of Arizona soon to be published by the Arizona Good Roads Association.

That same month, December 1912, Touring Topics carried an article headlined, "Still Another Nation-Wide Highway."

The good roads enthusiasts of northern Arizona and of San Bernardino County, in California, are agitating for the improvement of the old but little traveled transcontinental route which connects with the Santa Fe trail at Santa Fe, New Mexico, and extends westerly by way of Albuquerque, Nation's Ranch, the Zuni Indian Cliffs, the Petrified Forest, Canyon Diablo, the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, Ask [sic] Forks, Kingman, Needles, Daggett, San Bernardino and thence over the Foothill Boulevard to Los Angeles.

The counties through which the road passed were cooperating to finance its improvement. San Bernardino County had pledged to pay whatever sum was needed to improve the road from San Bernardino to Needles. Mojave and Yavapai Counties in Arizona had guaranteed to raise $200,000 for the road from Needles through Kingman, Gold Roads, Seligman, Ash Forks to Williams. Cococino County "will aid" in improving the road past Flagstaff. "Easterly from Santa Fe, New Mexico," the article explained, "this highway will connect with the old Santa Fe trail which winds over the Raton Pass to Denver and easterly to Kansas City and Chicago."

The route was "already negotiable and in general does not present the difficulties of the more southerly routes." The article suggested that when the route is improved, it will "undoubtedly become one of the most popular of the nationwide highways." The towns along the route were "exerting themselves to secure its early construction." It added:

The earnestness with which they have addressed themselves to the problem is shown in the pledge of Needles and neighboring cities on the route to raise a purse of $8,000 to induce the next Los Angeles-Phoenix race to use this course, and as an earnest of its good intention it has already raised $1,000 of this amount.

On January 28, 1913, supporters gathered in Kingman for a convention to boost the route. On the 29th, they drove to San Bernardino where they finished organizing the Santa Fe-Needles-Grand Canyon National Highway Association "to encourage and foster the construction of a national highway from San Bernardino via Barstow and Needles, along the Santa Fe trail, through Arizona and New Mexico, to connect the Pacific with the Atlantic." They agreed on an emblem designed by George D. Hutchison, a Barstow businessman. The emblem consisted of a blue Greek cross within a red circle on a white background. The name of the highway appeared on the red circle. Buttons with the emblem were to be sold for $1 each to support the association's work. By April 11, 1913, the Eye reported that 60 buttons had been sold in the Barstow district, and a second batch had been made, for a total of 100.

Engineer Parker addressed the convention. Touring Topics (February 1913) described his talk:

Mr. Parker exhibited more than fifty colored lantern slides showing scenes along this highway that were of unusual beauty. In addition to the views a detailed map of the route was displayed and in connection with it Mr. Parker described the road building methods that could be more advantageously used. A telling point in this lecture was Mr. Parker's statement that, in addition to the scenic and topographical advantages of this route, it was further favored by the unlimited amount of natural good road material that exists throughout Arizona and assures the construction of a high-class road at a moderate cost.

The association planned its promotional activities, which included sending delegates to the automobile manufacturers convention at Indianapolis in February. Having heard of a plan for a $10 million transcontinental highway (the Lincoln Highway, as will be discussed later) to be built by the manufacturers, the association designated delegates to attend in an attempt to get a share of the money for their route. They also would attend the Second Federal Aid Good Roads Convention sponsored by AAA at the Raleigh Hotel in Washington, D.C. on March 6 and 7, 1913.

Misconception, 1913

The January 1913 issue of Better Roads printed a resolution passed by the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association, with Judge Lowe in attendance, during its annual convention in Santa Fe:

To the end that no misconception shall exist anywhere as to the absolute affiliation, cooperation, and mutual good will of these associations, the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association will cordially lend any proper aid to the organizing force of the National Old Trails Association in securing memberships in the States of California, Arizona, and New Mexico, and the National Old Trails Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association by its president renews and reiterates the declaration of good will and cooperation stated in its constitution and reiterates its purpose to faithfully and earnestly cooperate with the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association, and will lend any proper aid to the organizing force of the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association in securing members in the territory of the National Old Trails Ocean-to-Ocean Association in consummating the great purpose of the two associations.

The magazine did not explain what misconception prompted the resolution, but it apparently related to the western end of the National Old Trails Ocean-to-Ocean Road. Judge Lowe's activities appeared to favor the route supported by the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association, but the map of the National Old Trails Ocean-to-Ocean Road listed the extension as tentative.

The National Highways Association

Judge Lowe was an early supporter of the National Highways Association. Charles Henry Davis conceived the association to persuade the Federal Government to build a 50,000-mile network of national highways. Davis was a wealthy road contractor who disposed of his business to divorce his new association from any hint of commercialism. "The National Highways Association," according to its publicity director, "believes that, when established, these national highways will increase the wealth, the power, and the importance of this country as nothing else can do besides that which has brought civilization to the savage, wealth to the poor, and happiness to all--GOOD ROADS" (Better Roads, October 1911). Its initial motto was "The Biggest Thing Ever Conceived, The Easiest Thing To Do."

Judge Lowe fully supported the goal of national highways, so his involvement was natural. The National Highways Association was incorporated in the District of Columbia in early 1912, with Judge Lowe as a Vice-President. General Coleman Du Pont, the wealthy good roads advocate who built the Dupont Highway in Delaware, was the Chairman of the Board of National Councillors. A. L. Westgard became a Vice-President and Director of Transcontinental Highways in 1913. Many named trail associations were affiliated with the National Highways Association, which called them "departments" or "agencies." For example, Judge Lowe was not only President of the National Old Trails Road Association, but President of the National Old Trails Road Department of the National Highways Association.

To read about the National Highways Association, see: www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/davis.cfm

On Capitol Hill

In national elections held in November 1912, the American people chose a new President, Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey. In anticipation of the 64th Congress that would convene in 1913, Representative introduced H.R. 28188, the latest version of his National Old Trails Road bill, on January 17, 1913. It authorized $20 million for construction of "The National Old Trails Road," which the bill described by identifying the cities it would pass through, including its route through the Southwest: "via La Junta and Trinidad in Colorado; via Santa Fe, Socorro, and Las Cruces in New Mexico; via Douglas, Phoenix and Yuma in Arizona; via El Centro, San Diego, and Los Angeles in California." As with all similar bills, H.R. 28188 was referred to committee.

Judge Lowe was in Washington on February 11 to testify before the Joint Committee on Federal Aid in Construction of Post Roads. His testimony began at 8 pm with Representative Dorsey W. Shackleford, the acting chairman, and Representatives Martin B. Madden and Richard W. Austin in attendance.

Congressman Dorsey W. Shackleford Click on image for larger version |

Shackleford, who was from Sweet Springs, Missouri, had introduced a bill in 1912 that would have authorized $25 million a year out of the Federal surplus to improve rural free delivery routes based on the quality of the road. Under Representative Shackleford's bill, all roads over which the mails were carried would be classified as A, B, or C roads. The Federal Government would "rent" the use of these roads from the States for mail by paying $25 per mile for Class A roads (macadam), $20 for Class B roads (gravel), and $15 for Class C roads (dirt). While leaving the roads under State control, Shackleford believed the proposal would provide a stimulus to road improvement and benefit farmers throughout the country. He also believed that by reducing the cost of delivering the mail, the bill would save money for the Federal Government, which was losing $28 million a year on rural free delivery.

Although the bill had passed the House, 240 to 86, on May 2, 1912, it failed in the Senate on August 13. Opposition from the automobile interests, particularly AAA, was a factor in the Senate defeat of Shackleford's farm-oriented rental plan in the Senate. However, the Administration--that is, Director Logan Page of the Office of Public Roads-also opposed the plan, on the grounds that the allowance per mile would not result in any significant amount of good roads.

In testimony on February 11, 1913, Judge Lowe began by describing the National Old Trails Road Association, and its work in promoting the building or rebuilding and maintenance of a 3,180-mile national road from Washington to California over historic trails, including the El Camino Real of New Mexico and the trails over which Doniphan and Kearney marched. He told the committee that he was not an expert road builder, but based on the cost of macadam roads in Jackson County, he estimated a 16-foot wide macadam road would cost $6,000 per mile or $18.6 million. Approximately 25 million people lived within a day's automobile drive of the route.

The Federal Government, he said, should build the road and maintain it. Asked if he was contemplating any other such roads, he said he was not:

I know that what is called the northern route-from New York, by way of Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, Chicago, Des Moines, Omaha, Denver, Salt Lake, and San Francisco-is strongly advocated by John Brisbane Walker and others, and it would be a magnificent and important national road.

He added that the route would be "out of commission on account of the weather" during much of the winter, while his central route "would be good at least 10 months out of the year, if not the entire year."

When Representative Austin pointed out that the central route went through 11 States, and would not help the other States, Judge Lowe agreed that the other States should have national roads as well:

I will say, by way of emphasis, that as president of the National Old Trails Association, we stand first for that, because that was the purpose and object of our creation, yet, if there is another road equally national in character, of equal importance commercially, or equal historic interest, and of every other kind of interest that might enter into the question, that ought to have precedence, then we will gladly give way and throw our entire organization behind that kind of a movement.

Representative Madden asked Judge Lowe for his views on the idea that the States should cooperate with the Federal Government in the construction of roads. Judge Lowe explained that he initially favored should a plan:

I believed that there ought to be close cooperation between the States and the National Government, and the National Government, perhaps, would hardly be justified in aiding any State unless the State showed a willingness to do something itself, but I have abandoned that idea entirely.

He did not like the concepts of "aid" or "cooperation," he said:

If all the States would "cooperate," and all the counties through which a road ran would "cooperate," and do it loyally and honestly, it might work; but when you divide responsibility and authority, and one would wait on the other, I question whether you would ever get a system of good roads . . . . I started out with the idea that they ought to be made to "cooperate," and the more I have thought of that the more I have thought it would lessen the prospect of going ahead-that it would retard road building rather than encourage.

He favored a national system of roads built by the Federal Government "and let the States build theirs." The Federal Government should appropriate $20 to $25 million a year and build a transcontinental road each year. He also rejected the notion that the States could be counted on to maintain the road if the Federal Government built it:

I think the whole question of maintenance was pretty well illustrated in the history of the old Cumberland Road. [Henry] Clay pronounced that as the greatest roadway in the world after it was finished, and he had seen the best roads. There may have been some burst or oratory in his statement, but . . . there was a magnificent highway built by the Government and maintained by it for more than a quarter century, and they turned it back to the States and it immediately went into decay and ruin.

Asked to comment on Representative Shackleford's bill, Judge Lowe remarked that the main thing he liked about the bill was that it acknowledged the Federal Government's authority to apply its funds to the building of roads. As for the funding provision in the bill, he said, "I am afraid the appropriation will be used, as public funds so often are, by scattering them out among the congressional districts and among the States and counties and be frittered away and no roads, practically, will be built."

In closing his testimony, Judge Lowe said:

I have one other matter I want to explain, and I want to say this with all the emphasis that it is necessary it should be said, and that is this: That our organization is not affiliated with nor interested in any organization of manufacturers of automobiles, or any other line of industry. We have not at any time been influenced by any position they may have taken, or anything of that character. We are as independent of any influence of that character as it is possible to be.

The contrast was with the Lincoln Highway Association.

The AAA Federal Aid Good Roads Convention

On March 6 and 7, Judge Lowe was in Washington for the AAA Federal Aid Good Roads Convention at the Raleigh Hotel, where he restated his views on the Federal role in road building. Representative Shackleford had addressed the convention the day before. In this setting, Judge Lowe felt freer to criticize the Shackleford bill than he had during his testimony:

I have been a farmer all my life. I only differ with Judge Shackleford in this, that he farms the farmer, and I run the farm. (Laughter.) You have always got to take in a man's environment. Mr. Shackleford's district is sort of a shoestring there. I wish I could point it out to you on the map, and I wish I had time to tell you about the people there. They are good people, splendid people, but I can say about a good many of them that when they move, and they move frequently, that a good many in the lower end of his district when they move simply have to call the dogs and put out the fire (Laughter.)

He referred to a farming community in the Congressman's district that had voted unanimously in favor of a bond for road construction:

Mr. Shackleford speaks of the people that are in favor of such a proposition as "high-brows." I do not care anything about how high their brows are, but I see that some of them are educated up to the point where they believe in building roads . . . .

Judge Lowe discussed the Old Trails Road, which he was certain could be finished in time for the Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915, but focused on the importance of national roads:

Let the authority over the National roads remain where of right it belongs, in the National Government, under the supervision and control of National authority. (Applause.) And let the States and counties manage their own affairs in their own way.

Now, let us get behind a single project. If it be not my project let it be yours, and if we decide on taking up some other proposition other than mine, I will back it with all the power I have. But let us get behind something definite, and stand for it, not only in this Convention, but when this convention adjourns and we go home let us stand for it; and talk for it; and if we do that before the Ides of next November you will see the Congress of the United States obeying our will and giving us the project we have been hoping for during all these long years. We will then come in and carry out a project that will do more for the up-building of the country; do more for the progressive ideas of the country; do more for the school system of the country; do more for the churches of the country; more for the patriotism and manhood and womanhood of the country than any project ever conceived in the mind of man. (Applause.)

Second National Convention, 1913

By the time the National Old Trails Road Ocean-to-Ocean Highway Association held its second annual convention on April 29 and 30, 1913, the Santa Fe-Grand Canyon-Needles National Highway Association was ready .

E. J. Kirker, representing the Old Trails Road, had visited Needles a few days earlier to perfect a branch organization. Kirker informed boosters that the decision on routing through the Southwest would be made at the annual meeting-and it would be a hard fight. As the Eye had explained in its April 26 edition, the "so-called Ocean-to-Ocean Highway via Yuma" had an advantage in population. Although the Needles boosters felt they had the advantage of climate, proximity to railroad, and accommodations, "the greatest advantage we have is that most of our road is built."

The 1913 convention was held in the Midland Building, the Old Trails headquarters in Kansas City. Estimates of delegates ranged from 250 to 400. However, even before the meeting began, G. D. Hutchison, representing the Grand Canyon route, was ready for what he called the hardest fight of his life. In the edition of May 9, 1913, the Eye explained that publicity had been his focus:

He saw the newspaper men first, told them his delegation was there to get the road, and nothing contributed to his success so much as that first impression on the newspaper men. He went immediately to the Star's art department and had a map made showing THE route to California. Barstow was marked by a flag, being the most important point on the road, of course. When the convention met, the principal thing in sight of the delegates was that map.

The debate on routing took place during the afternoon of April 29. An amendment was offered to amend the association's constitution to adopt the Grand Canyon Route between Santa Fe and the Pacific Coast as the official route of the National Old Trails Road. Either during this session or that evening, O. K. Parker spoke in support of the change:

The Santa Fe, Grand Canyon and Needles National Highway follows closely the route of the Santa Fe railway from Los Angeles to Santa Fe, the route being approximately that of the Kearney trail. It will form the western link of the Old Trails National Highway. There is a good road most of the way and by the middle of the summer it will be posted with signs. The posting of the Santa Fe trail will have been completed by that time, so there will be a well marked highway from Kansas City to the coast.

Aside from Hutchison's publicity efforts, another factor in the decision was creation of a new rival, the Southern National Highway. It had been established during a meeting in Asheville, North Carolina, on February 12-13, 1913. Governor Locke Craig of North Carolina had called the convention with the principal object of choosing a route from Washington, D.C., to connect with the El Paso-San Diego road. Dell Potter, who had played a key role during the first Old Trails Road convention in support of the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, was elected president of the Southern National Highway Association.

With the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway now part of a rival transcontinental highway, delegates to the Old Trails convention adopted the Grand Canyon Route as the Pacific Coast link. It was not a certain thing, though, as the Eye explained:

As soon as the motion was carried to make this the main road, some of our delegates rushed out to wire the good news home-before the chairman had declared the motion carried. The borderland delegates took this opportunity to continue the debate, but our warhorse [Hutchison] kept them at bay until the other delegates returned to cinch the road.

The constitution was amended to adopt the official route west of Santa Fe:

through Albuquerque and Gallup, New Mexico; Holbrook, Winslow, Flagstaff, Williams, Ashfork, Seligman, Kingman, Yucca, and Topeka [Topock], Arizona; Needles, Coffs [Goffs], Bacdad [Bagdad], Barstow, San Bernardino, Upland, San Gabriel to Los Angeles, and from Barstow through Bakersfield, Corcoran, Fresno, Merced, Stockton to San Francisco, California.

US Map showing location of Old Trails Road Click on image for larger version |

Recognizing that the adopted route, especially across western New Mexico, was not ready for automobile traffic, t he association approved a detour through Socorro and Magdalena, New Mexico, and Springerville and St. Johns, Arizona.

The association also dropped "Ocean-to-Ocean" from its name. Hereafter, it was known simply as the National Old Trails Road Association. The new slate of vice presidents and state organizers reflected the change as well. California would now be represented by Hutchison (vice president) and Ralph E. Swing (organizer) of San Bernardino. John R. Whiteside (vice president) of Kingman and Father Cypriano Rian Vabre of Flagstaff represented Arizona. The representatives from New Mexico were Harvey M. Shields (vice president) of Dawson and C. C. Manning of Gallup.

Although the routing decision had been the most important action of the convention, the delegates had much else to occupy them. During the first day, several addresses were presented, including one by Professor Williams. That evening, Miss Gentry presented an illustrated address on the "Old Trails Road." She was followed by Stanton Warburton, who had represented the State of Washington for one term in the U.S. House of Representatives (March 4, 1911 through March 3, 1913). During that term, he had introduced a bill calling for Federal construction of trunk highways linking Washington to the State capitals. He told the delegates:

The government soon or late must build and maintain national roads. Any other system of extensive road building only opens a door to graft and makes impossible a national system of highways. The Shackleford Bill is a pork barrel scheme providing for state aid in small amounts . . . . I claim above all else for my plan that it treats every State alike, large or small, rich or poor, and, furthermore, that my system will serve the greatest number of people. My plan provides for eighteen thousand miles of highways, and, on or within ten miles of these highways, live two-thirds of the inhabitants of the United States.

I would have the government build the best road that can be built and by that I do not mean a macadamized road, for that is not the best . . . . I will insist upon eighteen thousand miles of pavement in my system, pavement equal to the best in the streets of your city. My roads will cost from $15,000 to $20,000 a mile and it means a total cost of about 300 million dollars. The figure at first staggers congressmen to whom I have outlined my project. They ask breathlessly, "How will you raise the money?"

I propose to obtain the money by increasing the tobacco tax, the least taxed luxury in America. By increasing the tobacco tax to where it was in 1879 the government will acquire 70 million dollars a year, which will build my system and pay for it in five years.

During a similar speech to the AAA Federal Aid Good Roads Convention, Warburton had been asked what type of pavement he preferred. He responded, "Brick or cement, whatever is the best, I don't care what it costs--$15,000 or $20,000 a mile-because in the long run the best is the most economical thing to do." He also explained that the tax on tobacco had been lowered because Congress had been concerned about the growing surplus in the treasury. At that point in his speech, Judge Lowe asked how the war with Spain had been financed in 1898. He knew the answer, but Warburton replied, "We fought the war with Spain by doubling the internal revenue tax on smoking tobacco, chewing tobacco and snuff." After the war, the tax had been reduced to the 1879 level.

According to an account of the Old Trails convention in the June 1913 issue of Southern Good Roads, Warburton's "address probably attracted more attention and provoked more discussion than any other feature of the convention." His ideas were reinforced by Charles Henry Davis, who addressed the delegates regarding his bill to establish a National Highways Commission that would determine which roads should be built. He had nothing but contempt for "Federal-aid," as he explained:

"What's in a name?" has been asked. Everything or almost everything! "Give a dog a bad name and it sticks to him." It is the same with roads. They are now laboring under that infernally confusing, false, and misleading epithet, "Federal Aid." Responsible for delay in Congressional action! Responsible for the continuation of the activities of those more interested in their individual advancement than in the attainment of good roads! ...It can be made to mean anything which suits the selfish desires of the user! Indefinite! Alluring! Uncertain! Vicious! It does not spell GOOD ROADS!

If Federal-aid became a law, he said, people would awaken one day "to the fatal error and their ignorance in permitting such extravagance, incompetence, and graft as the result thereof." He favorably quoted Judge Lowe:

And, as your President has said, "By the Eternal" we will provide so-called statesmen responsible therefore "with a long and much needed vacation."

During the afternoon of April 30, the delegates were given an automobile tour of the city's boulevard, courtesy of the Kansas City Automobile Dealers' Association and the Kansas City Automobile Club. In the closing session later that day, the delegates unanimously re-elected Judge Lowe as President and association secretary Frank Davis of Herrington, Kansas. Miss Gentry was named Honorary Vice-President, while Professor Williams remained Advisory Vice-President.

The delegates adopted 15 resolutions, constituting according to Better Roads magazine, the "strongest road platform ever made." Resolution No. 1 stated:

That it is with the deepest respect we express our profoundest appreciation of the devoted, unselfish and patriotic service to the cause of the National Old Trails Road, and to this organization [by] that splendid and powerful association, the Daughters of the American Revolution, whose untiring zeal and consecrated devotion has done more than all others in preserving to future generations the memorable roads and landmarks in the pioneer history of this country, and that we will hold in everlasting remembrance their invaluable service to the great purpose we have so much at heart.

Resolution No. 2 sent greetings to residents of Ohio who had been devastated by floods, but whose legislature had voted a one-half mill tax to restore roads, including the old National Road. Similarly, Resolution No. 3 encouraged residents of Missouri to support a constitutional amendment that would authorize a one mill level for roads.