There are a variety of ways in which the public sector can either solicit or receive unsolicited input from the private sector during different stages of the project development process. This chapter and Table 2-1 summarize strategies for involving private sector entities while P3 projects are being initially identified and screened in the planning phase prior to procurement. The mechanisms may be used by public agencies to solicit and gain increased feedback from the private sector on potential P3 viability and project development strategies.

| Mechanism | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| P3 Program Development and Project Screening | The planning branches of State, metropolitan, and/or local transportation agencies develop criteria for screening projects in their short range and/or long range plans for P3 potential. Additional technical, financial, and value for money analysis is conducted on the screened projects and information made available for public review including the private sector project development community. The resulting P3 pipeline of projects may be adopted and periodically updated by the agency's governing body. |

|

| Industry Forums | Pre-procurement meetings with developers, financiers, construction companies, and other interested parties to gauge private interest in candidate P3 projects and P3 procurement strategies and to identify ways to enhance project viability as a P3. |

|

| Market Sounding | Separate, one-on-one discussions are conducted with developers and advisors to assess financial feasibility, risk allocation, and other related topics. |

|

| Request for Information (RFI) | Interested parties formally respond to a list of questions on potential technical solutions, financial packages, and/or risk allocation. |

|

| Unsolicited Proposals | Private sector developers provide an initial project concept without a formal request for qualifications or proposals, or in response to an open solicitation without reference to a specific project or scope. |

|

| Pre-Development Agreements (PDA) and Master Development Agreements (MDA) | Private contractors or consortia compete for the right to develop project design and/or environmental permitting in collaboration with the procuring agency and then have the right of first refusal to develop the project. |

|

| Progressive Design-Build Agreements | Through a qualification-based procurement, the Design-Build contractor is selected prior to preliminary design or a construction cost estimate. |

|

| Collaborative Risk Workshops | Private entities are invited to participate in pre- procurement risk workshops to be able to better assign risk to minimize overall cost. | N/A |

| Collaborative Evaluation of Project Alternatives | Very early in the project development process, while projects are not yet fully defined and environmental review is in progress, private entities are invited to participate in discussions regarding potential project alternatives. | N/A |

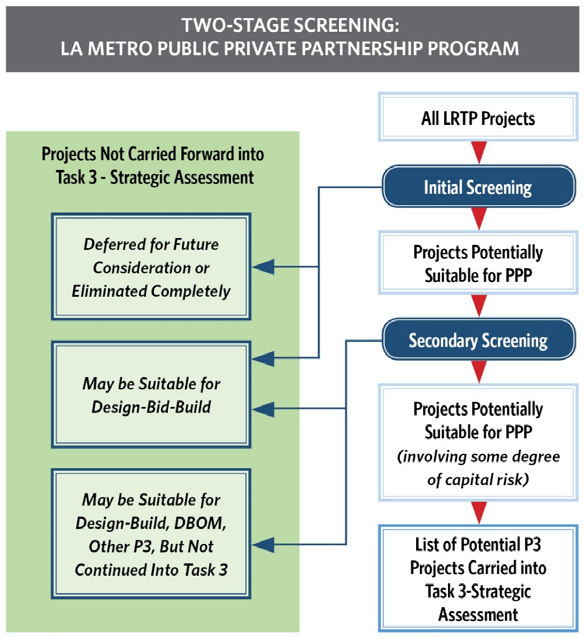

Under P3 enabling legislation, the state or metropolitan transportation agency or a special entity is designated to develop policies and procedures for screening, developing, procuring, and ultimately implementing P3 projects. Within TxDOT, for instance, the Strategic Project Division (SPD) was 1 responsible for project identification and development; within Virginia, the Office of Public-Private Partnerships (VAP3) is responsible for developing, procuring, and implementing the state's program of projects. LA Metro also employed a screening process, as illustrated in Figure 2-1. An initial step in the P3 program development process is for the agency to identify a subset of projects with P3 potential by screening projects proposed in its short- and long-range plans against pre-established agency goals. Some agencies also allow for candidate P3 projects to be proposed by their member agencies and/or by the private sector through an unsolicited proposal process (see below). Some agencies engage public officials and MPOs in the screening of projects. MPOs may also serve to educate stakeholders on the requirements to advance and implement a P3 project. The pipeline of potential P3 projects may be adopted by the agency's governing body and updated periodically to provide the basis for advancing candidate projects for P3 consideration and development.

Figure 2-1. Two-Stage Screening Process: LA Metro Public-Private Partnership Program

Text of Figure 2-1. Two-Stage Screening Process: LA Metro Public-Private Partnership Program

(Flow Chart)

| All LRTP Projects ↓ |

|

| Initial Screening ↓ |

|

| Deferred for Future Consideration or Eliminated Completely | May be Suitable for Design-Bid-Build |

| ↓ Projects Potentially Suitable for PPP |

|

| ↓ Secondary Screening |

|

| May be Suitable for Design-Bid-Build | May be Suitable for Design-Build, DBOM, Other P3, But Not Continued into Task 3 |

| ↓ Projects Potentially Suitable for PPP (involving some degree of capital risk) |

|

| ↓ List of Potential P3 Projects Carried into Task 3 Strategic Assessment |

|

The following factors may be considered by the public sector during the screening, initial planning, and pre- procurement planning and environmental processes, to stimulate private sector input and improve the likelihood of success of P3 projects:

Advantages. While not per se a mechanism for obtaining private sector input, the P3 program development and project screening process addresses a number of considerations important to the private sector project development community. Agencies with successful and mature P3 programs have clearly defined policies, procedures, and criteria for P3 project screening, evaluation, and approval, with opportunities incorporated for public review and input. Development of a list of candidate P3 projects indicates to project developers the agency's commitment and its priorities for project development. Preliminary technical, environmental, and financial feasibility studies developed by the agency to support project screening may save private sector time and expense. In addition, to reduce potential for downstream delays during procurement and/or contract or concession award and approval, the roles and responsibilities of the legislature and of oversight agencies are clearly defined and incorporated up front.

Disadvantages. Unless carefully developed, P3 enabling legislation and policies may be overly restrictive in defining the types of projects eligible for consideration, require multi-level sequential approval of contracts and/or concession agreements, or contain provisions that limit flexibility to respond to specific project needs. Legislation and policy must balance flexibility with protection of the public interest.

Applications. P3 enabling legislation and clearly defined policies, roles, and responsibilities for P3 program development and project screening have provided the basis for states such as Texas and Virginia to plan, implement, and oversee operations and maintenance of multiple P3 projects. Such programs demonstrate to the private sector that the agency is competent and timely, and has the ability to deliver, while also providing assurance to elected officials, appointed bodies, and the public that the projects advanced are in the interest of the public good.

Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) Office of Major Project Development (OMPD) and the CDOT High Performance Transportation Enterprise (HPTE) Industry Forum Guidelines

Industry forums may be held once the P3 Project Team has developed adequate information to share on the proposed P3 project, such as a tentative project scope, timing, procurement and finance approach, key technical elements and related information. The focus of industry forums is to share and gather information to help develop the best P3 project, delivery approach and process that delivers the best value to the State. Industry forums generally include:

Source: HPTE/CDOT

Industry forums are initial meetings held with infrastructure developers, equipment suppliers, investors, and advisors to demonstrate public sector support and commitment, and to assess the level of private sector interest in a proposed project or set of screened candidate projects. The procuring public agency has the option of keeping these discussions scripted or open-ended, brief or long, and bilateral or multilateral meetings with multiple parties. As an example, a one-day P3 Institute event was held in Miami at which public and private sector participants discussed some 60 potential P3 projects; this event could be replicated in other cities to similarly address potential projects in different regions.

Advantages. Industry forums have been successfully used by public procuring agencies to:

An indirect advantage of industry forums is that these discussions can sometimes facilitate the formation of private consortia.

Disadvantages. Among the disadvantages associated with industry forums are the potential for low attendance for difficult to finance projects. This may limit the value of the industry forum and not provide sufficient feedback on how to improve project bankability. If scheduled to take place too early in the project development process, there may be limited information that can be shared, thereby limiting the value of the forum. Legal and process requirements for maintaining competitive neutrality may effectively restrict the number and type of questions asked by the public agencies, the scope of private sector responses, and the corresponding Q&A discussion that can occur. 2 Other factors are that some bidders place greater confidence in written, rather than oral discussions. In addition, there may be limited feedback from potential proposers in a public forum in the presence of their competitors. For small projects or less-populous jurisdictions, the implementation costs associated with industry forums (and similar outreach activities) may be prohibitively high.

Applications. Industry forums are frequently used to initiate the P3 procurement process in the United States. Industry forums are informal mechanisms for the public procuring agency to meet with private sector entities and exchange project-related information. They also may serve as a project-screening tool. This approach may be combined with other methods for engaging with the private sector during the early stages of P3 project development.

Tips for a Successful Market Sounding Exercise

Source: Adapted from the World Bank, How to Engage with the Private Sector

Market sounding (or "soft" market testing or market consultation) is an approach used in Canada, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States that is similar to industry meetings. Under this bilateral process, public agencies conduct discussions not only with developers but also with technical, financial, and legal advisors. The information exchange during market sounding is bi- directional, with public project sponsors learning about the capabilities of the private sector, while the private sector learns about the goals and plans of public project sponsors. Compared to industry meetings, the market sounding process can allow for more open and honest discussions regarding financial and technical feasibility and risk allocation.

Advantages. This approach can be useful in providing insight into ways to craft a P3 project to maximize the level of market interest by better aligning public objectives with what can be reasonably delivered by the private sector. It is relatively easier to obtain input from private entities in a one-on-one conversation compared to an industry forum. The market sounding process may suggest major changes in project design and scope, identify technical and environmental issues, modify the risk allocation profile, and suggest changes to major project assumptions. Private sector feedback on overall technical and financial feasibility can assist public agencies in deciding whether to proceed with the project and whether the project can be effectively delivered through a P3.

Disadvantages. This approach typically requires that the procurement agency have a good understanding of the market, pre-existing relationships with developers and advisors, and an institutional structure that is aligned toward a possible P3 procurement. If these discussions are overly informal or too few entities are consulted, this can potentially result in a biased process and decision. Further, there is a risk that the public project sponsor will measure the success of its market sounding efforts in terms of the number of private firms that express interest, rather than focusing on how best to add value to the project and the public at large. These forums can also be less effective when public sector sponsor representatives do not participate directly, relying instead on outside advisors. There is a risk that advisors may have a financial interest in the project going forward and could potentially bias the market sounding process; also, the sponsor may not appear to have a serious interest in the project if it is not present.

Applications. A formal market sounding process involving discussions with multiple parties can be useful during the early phases of project development, as multiple parties are more likely to espouse differing views on a project's technical and financial feasibility, helping to minimize potential biases regarding project development. The market sounding process can also serve as a project-screening tool. A broad range of participants should be contacted, including lenders, advisors, investors, and developers to obtain a diverse set of opinions with respect to project financial and technical feasibility. The necessary elements for conducting a successful market sounding process are summarized in Figure 2-2.

Figure 2-2. Market Sounding Process

Sources: World Economic Group (2013), Strategic Infrastructure Steps to Prepare and Accelerate Public-Private Partnerships and The World Bank, (2009) Attracting Investors to African Public-Private Partnerships: A Project Preparation Guide.

View larger version of Figure 2.2

Text of Figure 2.2. Market Sounding Process

(Flow Chart)

Public agencies use Requests for Information (RFIs) to solicit information about the capabilities of potential proposers, obtain the private sector's views regarding the technical and financial feasibility of a given project and the preferred delivery mechanism, and gauge the market's appetite for the possible transfers of project risk. Depending on circumstances, RFIs can take place early or late in the project development process.

Advantages. RFIs can help the public procuring agency develop an understanding of the market for a project and obtain feedback on the initial commercial terms. Specifically, the RFI process can demonstrate if there is sufficient market interest to proceed with a procurement and identify steps that could make a potential P3 opportunity more attractive to prospective bidders. In this way, it helps the agency to lay the foundation for the next steps in the P3 procurement, e.g., the issuance of a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) or a Request for Proposals (RFP). RFIs also provide the procuring agency with initial information on the capabilities of the potential bidders. They can additionally be used to collect information on the technical and financial feasibility of the project from different perspectives. Such information can then be used to modify the project scope, specifications, requirements and risk allocation. For public agencies with limited experience, an RFI can also inform its understanding of how to deliver a project through a P3. From the private sector perspective, RFIs have been the catalyst for the formation of bidding teams and consortia. RFIs can potentially provide an indication as to size and depth of the competition.

Disadvantages. For the public agency, the disadvantages associated with an RFI are the additional costs to prepare and review responses to an RFI as well as the potential increased duration of the project schedule, generally of some three to six months. For the private sector, RFI responses can be expensive with marginal benefit with respect to developing a successful tender for the project. Moreover, project design and feasibility may change considerably between the issuance of an RFI and an RFQ and/or RFP. Given the opportunity cost in terms of financial and human resources, private entities have often waited until there is a formal RFQ or RFP to express interest in a project.

Applications. RFIs may work best for public agencies that are relatively new in developing and procuring P3s and/or for projects with uncertain financial and technical feasibility. However, many of the benefits of an RFI can be achieved through an industry forum or market sounding process at lower cost and with less impact to schedule.

"LA Metro's approach to P3s is unique. It flips the script. The traditional project delivery approach is to define a project and invite the private sector to bid on it. The public agency tells the industry what it needs and lays out the parameters, and then proposers design a project scheme to fit it. This approach can be very effective in ensuring that we end up with the project requested, but it does not leave much room for the industry to bring ideas and innovations forward. Instead of starting with the project end in mind, at LA Metro we are starting with the outcomes and performance objectives, and leaving the development of the solutions to the private sector".

Source: March 31, 2016 Infra-Americas Interview with Joshua Shank, LA Metro Chief Innovations Officer

Some state and local agencies have P3 authorization legislation that allows for receipt and consideration of unsolicited P3 offers; others do not. If allowed, legislation or policies prescribe a process for reviewing unsolicited offers. An unsolicited proposal as defined under federal procurement rules, is "a written proposal for a new or innovative idea that is submitted to an agency on the initiative of the offering company for the purpose of obtaining a contract with the government, and that is not in response to an RFP, broad agency announcement, or any other government-initiated solicitation or program." (Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) 2.101)

For an unsolicited proposal to comply with FAR 15.603(c), and thereby preserve eligibility for federal funding, it must:

Perhaps most importantly, unsolicited proposals must clearly align with the public sector's needs and priorities, and not be entertained otherwise. Depending upon the state and its authorizing statute, the public sponsor may be able to negotiate a sole source contract with the unsolicited proposer or may be required to solicit competing proposals to perform the same scope.

In addition to considering unsolicited proposals that comply with the federal definition in FAR, some sponsoring agencies provide the opportunity for private developers to submit unsolicited proposals without any prior definition of scope either on a revolving basis or annually within a specified submittal timeframe. Such a solicitation without any defined scope, while not an "unsolicited proposal" from a federal perspective, is often informally referred to as calling for "unsolicited proposals", and state procurement laws may address either or both forms of "unsolicited proposals".

A notable example of a successful unsolicited proposal is the Cross City Tunnel project in Sydney, Australia, which resulted in five responses when it was put out to bid. This process resulted in a project cost reduction of $1.5 billion from original government estimates by reducing the project footprint, optimizing the construction staging concept, and taking advantage of new tunneling technologies.

Advantages. The benefits of unsolicited proposals can vary depending on the project. Some agencies accept unsolicited proposals on an ongoing basis while others such as Virginia and Pennsylvania accept unsolicited proposals twice yearly at specifically defined periods. For the procuring agency, the main advantage of an unsolicited proposal is that it allows the private sector to identify projects in which it would be interested in investing. Unsolicited proposals can serve to introduce technical or financial innovations that can benefit the procuring agency and project users and can accelerate the development of an environmentally cleared project that lacks sufficient funding (e.g., I-495 Express Lanes in Northern Virginia). Unsolicited proposals also can also allow private entities to suggest possible segments of independent utility with stronger bankability relative to the original project alignment. Additionally, unsolicited proposals can jump-start a P3 procurement process that attracts other industry participants into the market.

For the private sector proposer, unsolicited proposals are hoped to result in a "first-mover" advantage leading to eventual contract award. This advantage may be more perception than reality, however, given the typical requirement for an open competitive process following an unsolicited proposal that is determined to have merit. (To ensure that such a process is truly competitive, adequate time must be allowed for accepting competing proposals.)

Disadvantages. Unsolicited proposals can get ahead of environmental review, permitting, stakeholder involvement, and public outreach processes. The procuring agency may not have the legal authority to accept, or the institutional capacity or available staff resources to effectively review a proposal. The unsolicited proposal may involve a project that is a very low priority or not aligned with the objectives of the agency, and yet the agency will have to spend staff time evaluating it and responding to the proposer.

Public disclosure requirements may create disincentives for the private sector with regard to providing detailed information on the project beyond a general alignment and financial package. From a competitive standpoint, unsolicited proposals can discourage other potential proposers from preparing competing proposals due to the high costs involved, limited project information, or the relatively short timeframe to respond. 3 Unsolicited proposal can also create an inadvertent selection bias in favor of the initial offeror. Finally, unsolicited proposals create additional challenges in terms of public perception regarding the transparency and competitiveness of the procurement process if the initial offeror's proposal is accepted.

From the private sector's perspective, unsolicited proposals can be expensive to produce, typically require a fee to the public procuring agency, and are inherently risky, as there is no guarantee that the project will be procured or that the original offeror will be awarded the project. Depending on the statute or regulation in place, the public procuring agency may have the flexibility to avoid or delay the review of the unsolicited proposal. Additionally, the overall track-record with unsolicited proposals has been mixed. There are several examples of lengthy negotiations that did not result in contract award (e.g., State Road 54/56 in Pasco Country, Florida) or that concluded in the selection of a firm different from the original proposer at the end of a competitive procurement process (e.g., Trans-Texas Corridor).

Applications. Although unsolicited proposals can provide advantages for public and private sector entities, there are significant opportunity costs and risks for both parties. The number of transportation projects successfully developed as a result of an unsolicited proposal remains limited. As with the Capital Beltway HOT lanes project, unsolicited proposals have worked best when it has resulted in the acceleration of a planned and environmentally cleared project for which the public sector lacks sufficient financial resources.

Use of Pre-Development Agreements

PDAs may work best for large projects that are relatively undefined with respect to termini and cost, have not achieved environmental approval, or encompass different alternatives that require additional preliminary screening.

Under pre-development agreements (PDAs) (also known as master development agreements), private infrastructure contractors or consortia seek the right to develop a financially feasible project design in collaboration with the procuring agency, followed by the right of first refusal to develop the project on a P3 basis. The PDA is awarded on a best value basis to the most qualified proposer with the best development and financial plans.

Advantages. This approach enables the private sector to provide significant input to the definition of the project, including logical termini, strategies to reduce risks, capital costs, schedule, operations and maintenance requirements, and funding and financing packages. Although developers typically have greater interest in projects that have been environmentally cleared, in some cases developers are willing to perform the preliminary engineering at a partially deferred cost, at risk, and with full payment at financial close. At the end of the planning process, the project is more likely to be bankable, obtain debt financing, and reach close of finance. By working collaboratively, both parties can obtain a better understanding of the project's risk profile and have the opportunity to develop more effective risk mitigation strategies.

Disadvantages. The private sector, particularly infrastructure developers and investment funds, have indicated that they have little interest in acting as consultants and would prefer to implement DBFOM P3 projects, which is their primary business, and earn a return on their equity. Pre-development agreements are likely to reduce competition either as a result of "right of first refusal" clauses which give the awarded party the first right to bid on a project or selection biases in favor of the entity selected under the pre- development agreement. Pre-development agreements give the awarded party additional inside information that creates a competitive advantage or may dissuade other bidders from entering into an open competition for the project. Even if a collaborative environment has been established, this does not ensure that both parties will fully share information.

Applications. Pre-development agreements tend to work best if there is a collaborative working relationship between the project sponsor and the private partner that promotes the reasonable and effective sharing of project information by both parties. Statutory restrictions or procurement rules in some states may also explicitly prohibit the planning, environmental, or design entity for a project from bidding on its final design and construction.

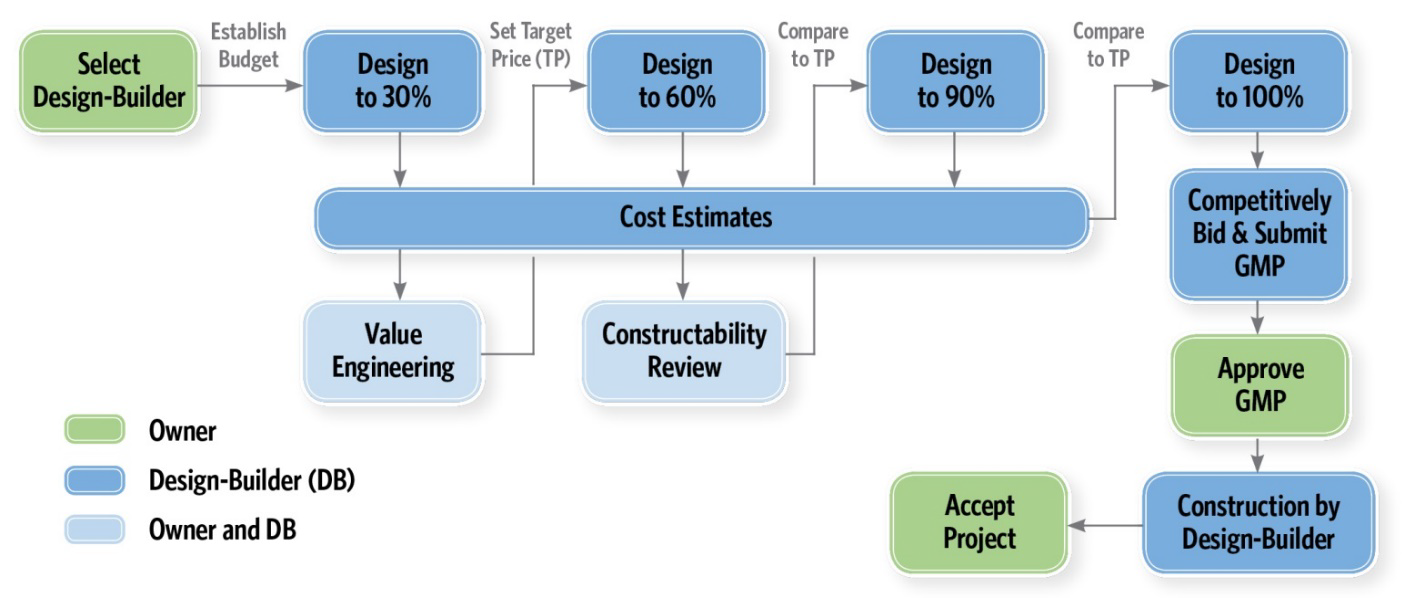

With progressive design-build agreements, the design-build contractor is selected primarily on qualifications and is brought on as part of the owner's team at a very early stage of project design. In contrast to project development through Construction Manager at Risk (CMAR) and Construction Manager/General Contractor (CM/GC) procurement approaches, the design firm and contractor are selected and contracted under a single procurement. The design-build contractor will either assist the owner in developing the design or advance the design from what the owner has already developed. At approximately 60 percent design, the design-build contractor submits a commercial proposal to complete design and construction for a fixed price and schedule with performance guarantees. Owners can use third parties to verify cost, and can complete a competitive procurement if the parties cannot agree to the design-build contractor's proposed cost. Figure 2-3 shows the roles of the public procuring agency and the design-build contractor under progressive design-build agreements as a project advances through design, competitive bidding, approval of the guaranteed maximum price (GMP), construction, and project acceptance.

Advantages. For the project sponsor, the main advantages of progressive design-build agreements are the potential to reduce procurement preparation and review costs, accelerate project procurement and development, and reduce capital costs. The ability to implement the project in phases or task orders increases flexibility for the public procuring agency in the project development process.

There is also greater potential for information sharing. For example, on the Silver Line extension to Dulles Airport (Phase 2) in Northern Virginia, the contractor conducted two workshops at the outset of the project. The first focused on the concept design in the environmental document, and the second addressed design concepts for line, track, systems, stations and parking components. The results influenced all aspects of the concept design. In total, the savings from all final recommendations from the Silver Line Extension workshop totaled $190 million, or 10 percent of estimated construction costs. 4 From the private sector perspective, progressive design-build agreements are attractive because they can potentially lower bidding costs depending upon the timing of the awarded construction contract.

Figure 2-3. Progressive Design-Build

Sources: Johnson (HDR) and Zeltner (HDR) Alternative Delivery: Progressive Design-Build

Text of Figure 2-3. Progressive Design-Build

(Flow Chart)

| Select Design-Builder → (Establish Budget) Assigned to: Owner |

Design to 30% → |

Design to 60% → (Compare to TP) Assigned to: Design-Builder (DB) ↓ |

Design to 90% → (Compare to TP) Assigned to: Design-Builder (DB) ↓ |

Design to 100% Assigned to: Design-Builder (DB) |

Cost Estimates |

Cost Estimates Assigned to: Design-Builder (DB) ↓ |

Cost Estimates Assigned to: Design-Builder (DB) |

↓ | |

| Value Engineering Assigned to: Owner & DB |

Constructability Review Assigned to: Owner & DB |

↓ | ||

| Competitively Bid and Submit GMP Assigned to: Design-Builder (DB) ↓ |

||||

| Approve GMP Assigned to: Owner ↓ |

||||

| Construction by Design-Builder Assigned to: Design-Builder (DB) ↓ |

||||

| Accept Project Assigned to: Owner |

Disadvantages. Progressive design-build agreements employ numerous task orders, creating a lack of construction cost certainty and reduced competition if final costs are determined through a negotiated process. There is also a selection bias at the 60 percent design submittal since the incumbent design-builder already has an ongoing contract with the procuring agency, potentially offsetting the cost advantages of broader competition. The incumbent design-build contractor also has a competitive advantage compared to other bidders since it has greater knowledge about the project as a result of the 60 percent submittal. Progressive design-build contracts may also increase post-procurement award costs and complexity, as the selected progressive design-build firms would be required to work with several of their counterparts within the team during the bid process.

Applications. Progressive design-build contracts have largely been used in water distribution and treatment projects. Transportation sector examples include the second phase of the Washington Metro Silver Line and the Maryland I-270 Innovative Congestion Management Project, for which an RFI was issued in late 2015. Because the design-builder will provide its overall project price commitment after contract award, the processes for negotiating the price must be carefully conceived by both sides.

Under this approach, private sector entities participate in risk workshops along with staff from the project sponsor, technical experts, and key stakeholders. Single or multiple workshops may be held depending on the number of participants involved.

Advantages. The workshops provide a neutral setting for a more comprehensive identification of project risks and the identification of potential strategies for the allocation and mitigation of these risks. The workshops normally lead to development of a refined risk-adjusted cost estimate and schedule, as well as guidance on risk allocation in the contract documents.

Disadvantages. To date, there has been limited industry experience with collaborative risk workshops, especially during the early phases of project planning. More critically, public and private parties are unlikely to provide sensitive commercial information lest they give up their competitive advantage within the industry and their negotiating position at contract award. Along these lines, both public and private parties have incentives to under-estimate or over-estimate risk impacts depending on the type and magnitude of the risk.

Applications. This approach has not been explicitly applied to date. Potential applications of collaborative risk workshops may be limited as the benefits of this approach can be achieved through pre-procurement industry forums or market sounding.

With collaborative workshops on project alternatives, prospective private infrastructure developers, lenders, and investors are invited to participate in workshops to identify, define, and refine possible project alternatives.

Advantages. If structured properly, collaborative workshops may be useful tools for identifying and refining potential alignments, project design, and funding and financing packages. The recommendations from these workshops would be non-binding to avoid biasing ongoing environmental reviews (if applicable), and to minimize concerns regarding selection bias.

Disadvantages. There is limited industry experience with the collaborative participation of the private sector in the review of project alternatives. Additionally, some stakeholders and the general public may develop the perception that this approach could bias the NEPA process by pre-determining an alignment and creating a lack of transparency in project and route selection; in reality, this is not the case as the NEPA process would objectively evaluate different alternatives including the product(s) of the workshop. Another potential disadvantage is the limited number of people that can effectively participate in a workshop. If all interested proposers send a representative, it may be too large of a group to allow a workshop to properly function. Turning away companies would not work either as it would give some firms an unfair competitive advantage.

Applications. This approach has not been implemented in the United States. The private sector can provide non-binding feedback on alignments through industry forums, market sounding, RFIs, and other feedback mechanisms. The NEPA process also allows the private sector to review and comment on alternative project alignments during the outreach process, similar to a member of the public; however, the private sector cannot have any direct involvement in the decision-making process; this limits the potential use of this approach.

1 Responsibilities under the TxDOT Strategic Project Division were reassigned during a recent reorganization; the Texas Center for Alternative Finance and Procurement was established in 2016 to (1) consult with governmental entities regarding best practices for procurement and the financing of qualifying projects; and (2) assist governmental entities in the receipt of proposals, negotiation of interim and comprehensive agreements, and management of qualifying projects under the state P3 legislation.

2 For example, TxDOT processes require that all participating firms receive the same information.

3 The time allotted to submit competing responses varies by jurisdiction, e.g., Florida has a 120-day limit.

4 Kane, Christopher, (2010) Using PPPs in the US to Develop, Finance and Operate Infrastructure Projects TRB 49th Annual Workshop on Transportation Law, Newport, Rhode Island.