Highlights

This edition of the C&P report is based primarily on data through 2012; consequently, the system conditions and performance measures presented do not reflect the impacts of the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21), which authorized Federal highway and transit funding for Federal Fiscal Years 2013 and 2014. None of the impact of funding authorized under the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act is reflected.

In assessing recent trends, this report generally focuses on the 10-year period from 2002 to 2012. The prospective analyses generally cover the 20-year period ending in 2032; the investment levels associated with these scenarios are stated in constant 2012 dollars.

Highlights: Highways and Bridges

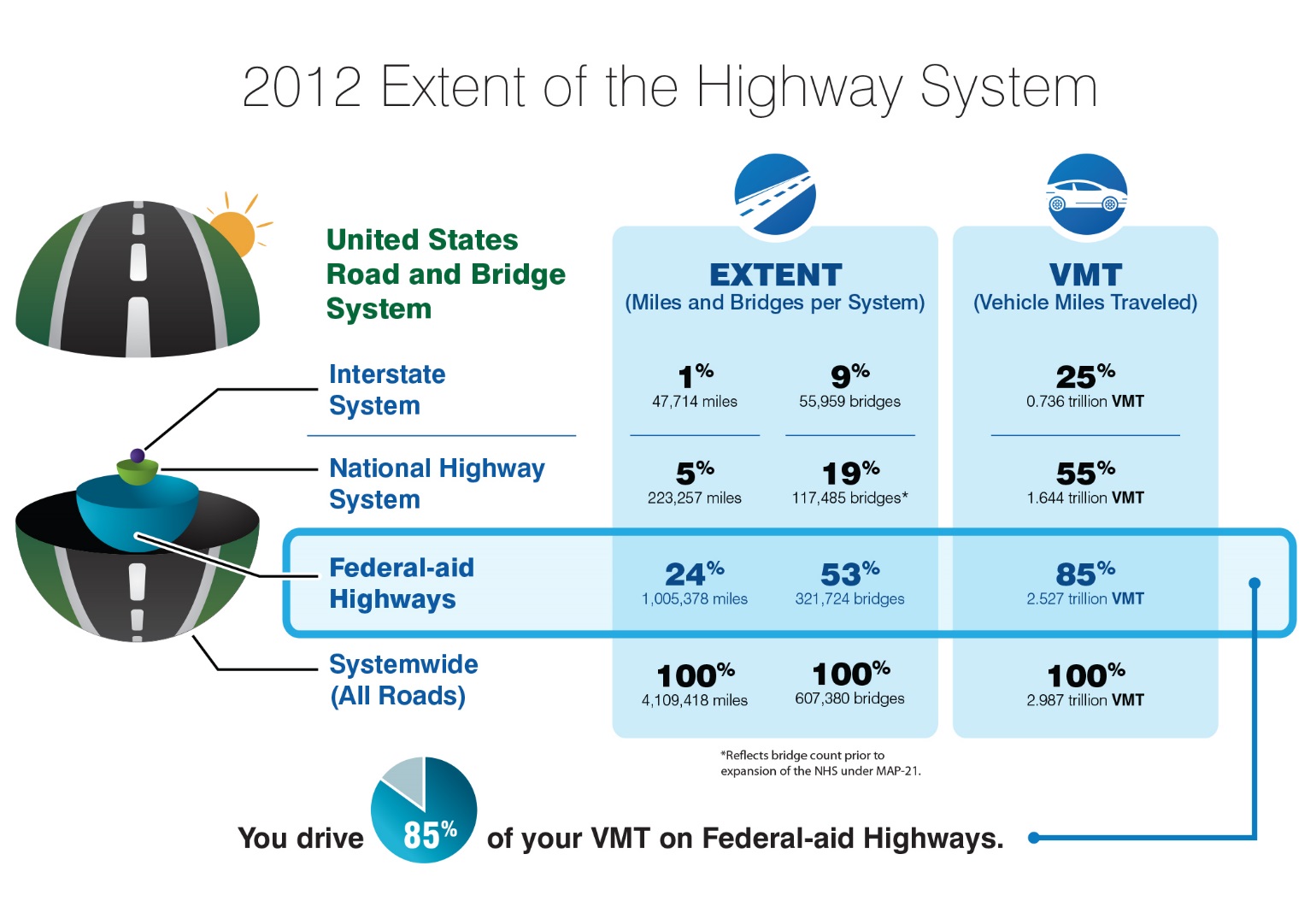

Extent of the System

Highway System Terminology

"Federal-aid highways" are roads that generally are eligible for Federal funding assistance under current law. (Note that certain Federal programs do allow the use of Federal funds on other roadways.)

The "National Highway System" (NHS) includes those roads that are most important to interstate travel, economic expansion, and national defense. It includes the entire Interstate System. MAP-21 directed that the NHS system be expanded. Except where noted, the statistics presented in this report reflect the expanded NHS.

- The Nation's road network included 4,109,418 miles of public roadways and 607,380 bridges in 2012. This network carried over 2.987 trillion vehicle miles traveled (VMT), and almost 4.275 trillion person miles traveled (PMT), up from 2.874 trillion VMT and down from 4.667 trillion PMT in 2002.

- The 1,005,378 miles of Federal-aid highways (24 percent of total mileage) carried 2.527 trillion VMT (85 percent of total travel) in 2012.

- Although the 223,257 miles on the National Highway System (NHS) comprise only 5 percent of total mileage, the NHS carried 1.644 trillion VMT in 2012, approximately 55 percent of total travel.

- The 47,714 miles on the Interstate System carried 0.736 trillion VMT in 2012, slightly over 1 percent of total mileage and just under 25 percent of total VMT. The Interstate System has grown since 2002, when it consisted of 46,747 miles carrying 0.694 trillion VMT.

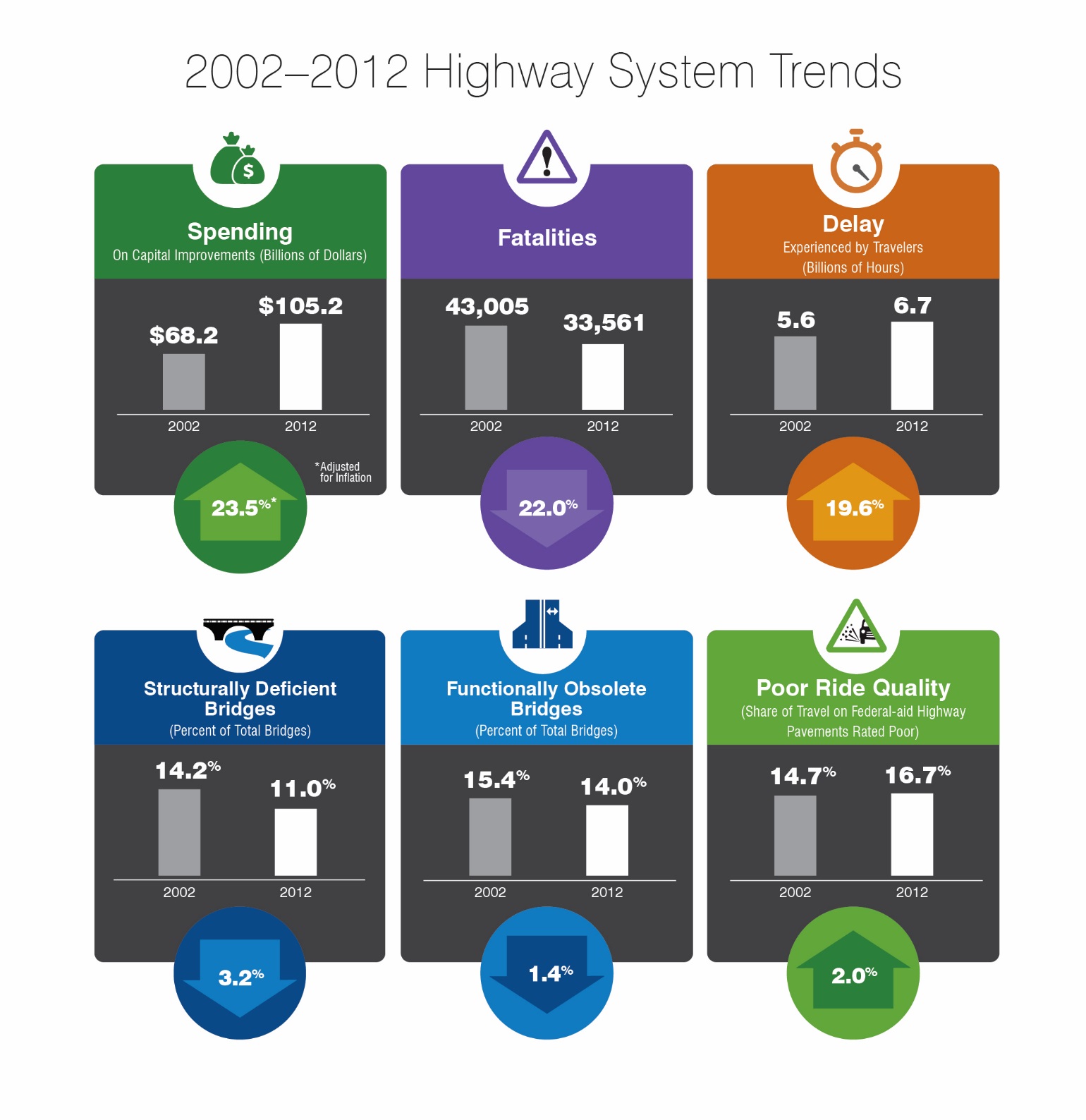

Spending on the System

- All levels of government spent a combined $221.3 billion for highway-related purposes in 2012. About 47.5 percent of total highway spending ($105.2 billion) was for capital improvements to highways and bridges; the remainder included expenditures for physical maintenance, highway and traffic services, administration, highway safety, and debt service.

- In nominal dollar terms, highway spending increased by 62.8 percent (5.0 percent per year) from 2002 to 2012; after adjusting for inflation, this equates to a 28.9-percent increase (2.6 percent per year).

- Highway capital expenditures rose from $68.2 billion in 2002 to $105.2 billion in 2012, a 54.3-percent (4.4 percent per year) increase in nominal dollar terms; after adjusting for inflation, this equates to a 23.5-percent (2.1 percent per year) increase in constant-dollar terms.

- The portion of total highway capital spending funded by the Federal government decreased from 46.1 percent in 2002 to 43.1 percent in 2012. Federally funded highway capital outlay grew by 3.7 percent per year over this period, compared to a 5.0-percent annual increase in capital spending funded by State and local governments.

- The composition of highway capital spending shifted from 2002 to 2012. The percentage of highway capital spending directed toward system rehabilitation rose from 53.1 percent in 2002 to 59.0 percent in 2012. Over the same period, the percentage directed toward system enhancement rose from 11.1 percent to 15.1 percent , while the percentage directed toward system expansion fell from 35.8 percent to 25.8 percent .

Constant-Dollar Conversions for Highway Expenditures

This report uses the Federal Highway Administration's National Highway Construction Cost Index and its predecessor, the Composite Bid Price Index, for inflation adjustments to highway capital expenditures and the Consumer Price Index for adjustments to other types of highway expenditures.

Highway Capital Spending Terminology

This report splits highway capital spending into three broad categories. "System rehabilitation" includes resurfacing, rehabilitation, or reconstruction of existing highway lanes and bridges. "System expansion" includes the construction of new highways and bridges and the addition of lanes to existing highways. "System enhancement" includes safety enhancements, traffic control facilities, and environmental enhancements.

Conditions and Performance of the System

The data systems and performance metrics for different aspects of system conditions and performance are at different stages of development. Progress is being made on measuring the impact of transportation investments on livability. Several resources and tools, such as the Location Affordability Portal, Sustainable Communities Indicator Catalog, Infrastructure Voluntary Evaluation Sustainability Tool, and the Community Vision Metrics Web Tool have been developed to measure the impact of transportation investments on quality of life.

Bridge Conditions Have Improved

FHWA Bridge Classifications

Bridges are considered "structurally deficient" if (1) significant load-carrying elements are found to be in poor or worse-than-poor condition due to deterioration or damage, or (2) the adequacy of the waterway opening the bridge provides is determined to be insufficient to the point of causing intolerable traffic interruptions due to high water. That a bridge is structurally deficient does not mean it is unsafe.

Functional obsolescence in general is a function of the geometrics (e.g., broad roadway width, load carrying capacity, clearances, approach roadway alignment) of the bridge in relation to the geometrics required by current design standards. The magnitude of such deficiencies determines whether a bridge is classified as "functionally obsolete."

These classifications are often weighted by bridge deck area, recognizing that bridges are not all the same size and, in general, larger bridges are more costly to rehabilitate or replace to address deficiencies. They are also sometimes weighted by annual daily traffic, recognizing the more heavily traveled bridges have a greater impact on total highway user costs.

- Based directly on bridge counts, the share of bridges classified as structurally deficient has improved, dropping from 14.2 percent in 2002 to 11.0 percent in 2012. The share of NHS bridges classified as structurally deficient also improved over this period, dropping from 5.9 percent to 4.5 percent .

- Weighted by deck area, the share of bridges classified as structurally deficient improved, declining from 10.4 percent in 2002 to 8.2 percent in 2012. The deck area-weighted share of structurally deficient NHS bridges dropped from 8.6 percent to 7.1 percent over this period.

Bridge Geometry Has Slightly Improved

- Based directly on bridge counts, the share of bridges classified as functionally obsolete declined from 15.4 percent in 2002 to 14.0 percent in 2012. The share of NHS bridges classified as functionally obsolete also improved over this period, dropping from 17.2 percent to 16.2 percent . Functional obsolescence tends to be a more significant problem on larger bridges carrying more traffic, such as those located on the NHS.

- Weighted by deck area, the share of bridges classified as functionally obsolete improved slightly, dropping from 20.4 percent in 2002 to 20.1 percent in 2012. The deck area-weighted share of functionally obsolete NHS bridges dropped slightly from 21.1 percent to 21.0 percent over this period.

- The annual number of highway fatalities was reduced by 21.4 percent from 2002 to 2012, dropping from 43,005 to 33,782. The fatality rate per 100 million VMT declined from 1.51 in 2002 to 1.14 in 2012. (Since 2012, the number of highway fatalities has risen to 35,092 in 2015; the fatality rate per 100 million VMT was 1.08 in 2015).

- The number of traffic-related injuries decreased by more than 19 percent , from 2.9 million in 2002 to 2.4 million in 2012. The injury rate per 100 million VMT declined from 102 in 2002 to 80 in 2012.

- Fatalities related to roadway departure decreased by 31.0 percent from 2002 to 2012, but roadway departure remains a factor in over half of all highway fatalities. Intersection-related fatalities decreased by 21.5 percent from 2002 to 2012, but over one-fifth of highway fatalities in 2012 occurred at intersections.

- In 2012, roadway departure, intersection, and pedestrian fatalities accounted for 52.2 percent , 21.7 percent , and 14.1 percent , respectively, of the 33,561 fatalities.

- From 2002 to 2012, the number of nonmotorists killed by motor vehicles increased by 1.1 percent , from 5,630 to 5,692. Since 2009, the number of pedestrians and pedacylists (such as bicyclists) killed by motor vehicle crashes has each increased by approximately 15.6 percent .

Highway Safety Improved Overall, but Nonmotorist Fatalities Rose

Pavement Condition Trends Have Been Mixed

- In general, pavement condition trends over the past decade have been better on the NHS (the 5 percent of total system mileage that carries 25 percent of total system VMT) than on Federal-aid highways (the 24 percent of system mileage that carries 85 percent of total system VMT, including the NHS).

- The share of Federal-aid highway VMT on pavements with "good" ride quality rose from 43.8 percent in 2002 to 44.9 percent in 2012. The share of mileage with good ride quality declined from 46.6 percent to 36.4 percent over this same period, however, indicating that conditions have worsened on roads with lower travel volumes.

- The share of Federal-aid highway pavements with "poor" ride quality rose from 2002 to 2012, as measured on both a VMT-weighted basis (rising from 14.7 percent to 16.7 percent ) and a mileage basis (rising from 12.6 percent to 19.7 percent ). Although this trend is exaggerated due to changes in data reporting instructions beginning in 2010, the data clearly show that more of the Nation's pavements have deteriorated to the point that they are adding to vehicle operating costs and reducing driver comfort.

- The share of VMT on NHS pavements with good ride quality rose from 50 percent in 2002 to 57.1 percent in 2012. This gain is even more impressive considering the significant expansion of the NHS under MAP-21, as pavement conditions on the additions to the NHS were not as good as those on the pre-expansion NHS. When adjusted for the NHS expansion, the share of VMT on NHS pavements with good ride quality improved by an average of more than 2 percentage points per year. The share rose from 50 percent in 2002 to 60 percent in 2010 based on the pre-expansion NHS and from an estimated 54.7 percent in 2010 to 57.1 percent in 2012 based on the post-expansion NHS.

Pavement Condition Terminology

This report uses the International Roughness Index (IRI) as a proxy for overall pavement condition. Pavements with an IRI value less than 95 inches per mile are considered to have "good" ride quality. Pavements with an IRI value greater than 170 inches per mile are considered to have "poor" ride quality. Pavements that fall between these two ranges are considered "fair"; the term "acceptable" combines the "good" and "fair" categories.

Operational Performance Has Slowly Worsened

- The Texas Transportation Institute estimates that the average commuter experienced a total of 41 hours of delay resulting from congestion in 2012, up from 39 hours in 2002. Total delay experienced by all travelers combined rose from 5.6 billion hours in 2002 to 6.7 billion hours in 2012, an all-time high.

- The combined cost of wasted time and wasted fuel caused by congestion rose from an estimated $124 billion in 2002 to $154 billion in 2012. Although these costs had declined during the recent recession, by 2012, they had reverted to their pre-recession peak in 2007.

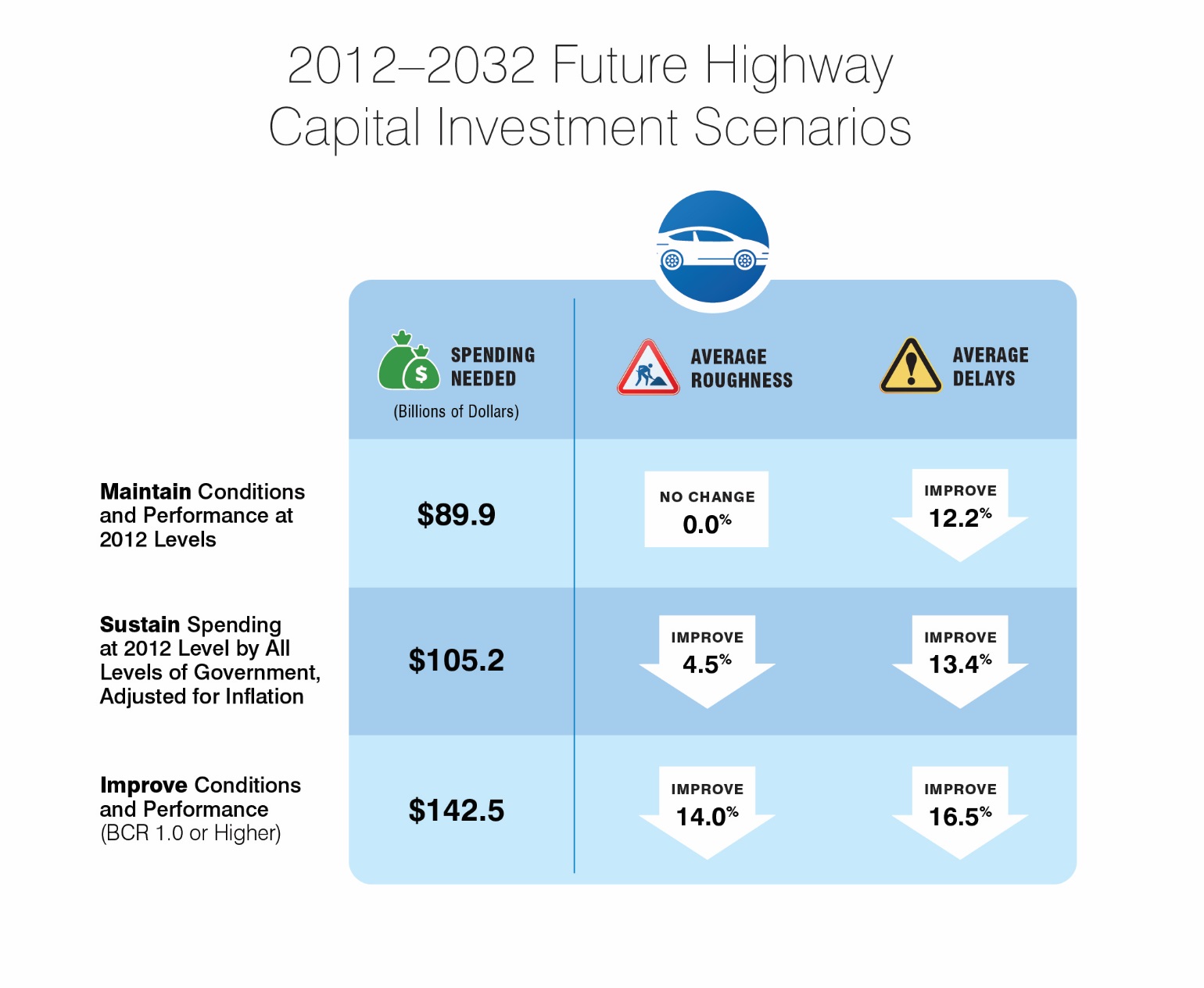

Future Capital Investment Scenarios — Systemwide

The scenarios that follow pertain to spending by all levels of government combined for the 20-year period from 2012 to 2032 (reflecting the impacts of spending from 2013 through 2032); the funding levels associated with all of these analyses are stated in constant 2012 dollars. The results below apply to the overall road system; separate results based on applying the scenario criteria separately to the Interstate System, the NHS, and Federal-aid highways, are presented in the body of this report.

Sustain 2012 Spending Scenario

Highway Investment/Performance Analyses

To provide an estimate of the costs that might be required to maintain or improve system performance, this report includes a series of investment/performance analyses that examine the potential impacts of alternative levels of future combined investment by all levels of government on highways and bridges for different subsets of the overall system. Rather than assuming an immediate jump to a higher (or lower) investment level, each analysis assumes that spending will grow by a uniform annual rate of increase (or decrease) in constant-dollar terms using combined highway capital spending by all levels of government in 2012 as the starting point.

Drawing on these investment/performance analyses, a series of illustrative scenarios was selected for more detailed exploration and presentation. The scenario criteria were applied separately to the Interstate System, the NHS, all Federal-aid highways, and the overall road system.

- The Sustain 2012 Spending scenario assumes that capital spending by all levels of government is sustained in constant-dollar terms at the 2012 level ($105.2 billion systemwide) through 2032. At this level of investment, average pavement roughness on Federal-aid highways would be projected to improve by 4.5 percent , while average delay per VMT improves by 13.4 percent . The share of bridges classified as structurally deficient would be projected to improve, declining from 8.2 percent in 2012 to 2.9 percent in 2032.

Maintain Conditions and Performance Scenario

- The Maintain Conditions and Performance scenario assumes that capital investment gradually changes in constant-dollar terms over 20 years to the point at which selected measures of future conditions and performance in 2032 are maintained at 2012 levels. The average annual level of investment associated with this scenario is $89.9 billion, 14.6 percent less than actual capital spending by all levels of government in 2012.

Improve Conditions and Performance Scenario

- The Improve Conditions and Performance scenario assumes that capital investment gradually rises to the point at which all potential highway and bridge investments that are estimated to be cost-beneficial (i.e., those with a benefit-cost ratio [BCR] of 1.0 or higher) could be funded by 2032. The average annual level of systemwide investment associated with this scenario is $142.5 billion, 35.5 percent higher than actual 2012 spending.

- As of 2012, the United States had an estimated $836 billion of unmet capital investment needs for highways and bridges that would be cost-beneficial to address. The Improve Conditions and Performance scenario would eliminate this backlog, while addressing other needs as they arise over 20 years through 2032. Eliminating this backlog would require increasing highway capital spending by 2.81 percent per year faster than the rate of inflation.

- Under the Improve Conditions and Performance scenario, average pavement roughness on Federal-aid highways is projected to improve by 14.0 percent , while average delay per VMT is projected to improve by 16.5 percent . The share of bridges classified as structurally deficient is projected to improve, declining from 8.2 percent in 2012 to 1.9 percent in 2032.

- The State of Good Repair benchmark represents the subset of this scenario that is directed toward addressing deficiencies in the physical condition of existing highway and bridge assets. The average annual investment level associated with this benchmark is $85.3 billion. This level of investment would not eliminate all poor pavement or structurally deficient bridges because, in some cases, addressing such deficiencies until after they arise would not be cost-beneficial. Therefore, at the end of any given year, some portion of the pavement and bridge population would remain deficient.

Highlights: Transit

Extent of the System

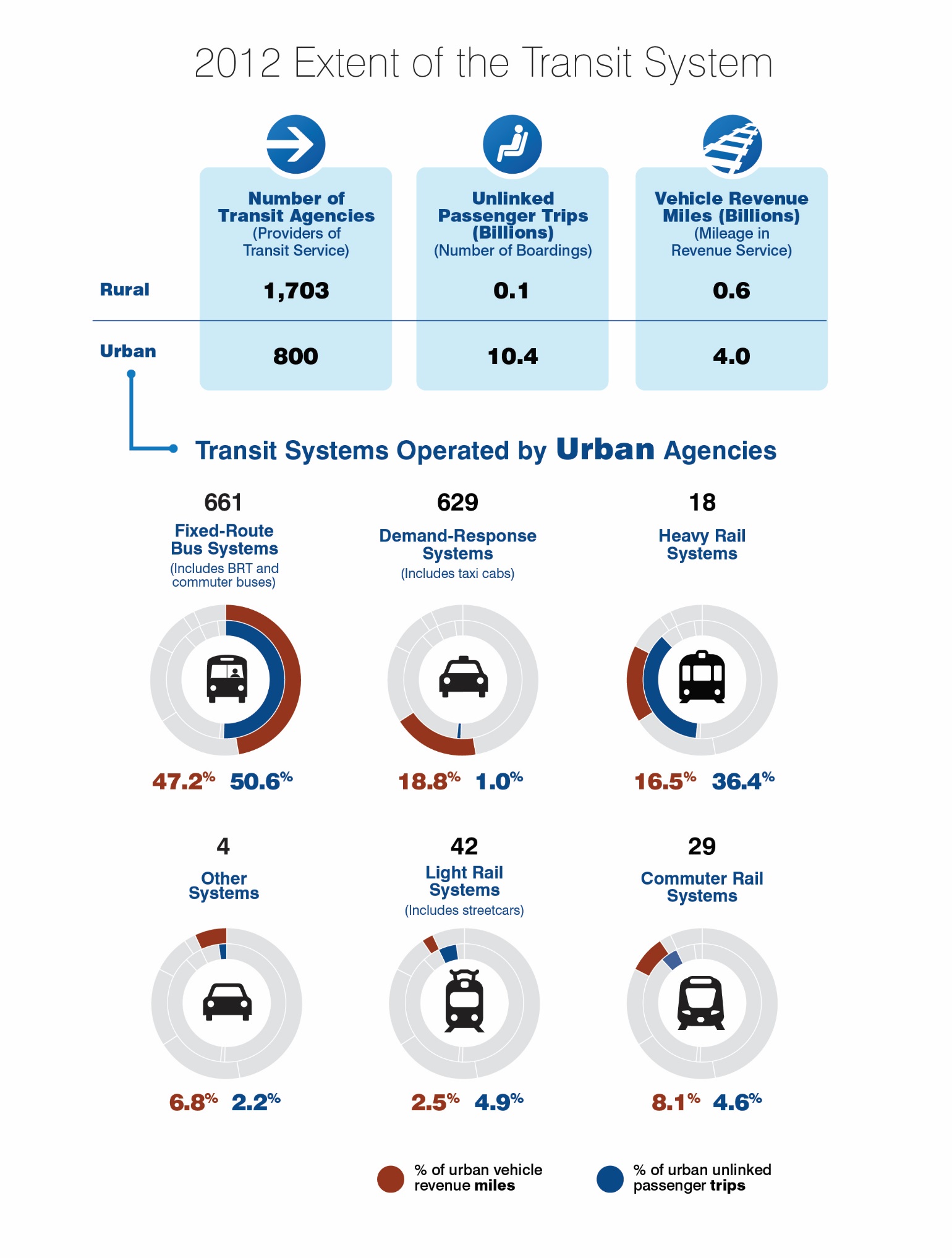

- Of the transit agencies that submitted data to the National Transit Database in 2012, 800 provided service to urbanized areas and 1,703 provided service to rural areas. Urban agencies operated 661 bus systems, 629 demand-response systems, 18 heavy rail systems, 29 commuter rail systems, 25 light rail systems, 17 streetcar systems, and 4 hybrid rail systems. Additionally, 74 transit vanpool systems, 23 ferryboat systems, 5 trolleybus systems, 8 monorail and automated guideway systems, 3 inclined plane systems, 1 cable car system, and 1 Público were in operation.

- Bus and heavy rail modes continue to be the largest segments of the industry, providing 50 percent and 36 percent of all transit trips, respectively. Commuter rail supports a relatively high share of passenger miles (20.0 percent ). Although light rail is the fastest-growing rail mode (with passenger miles growing at 5.7 percent per year from 2002 to 2012), it still provides only 4.0 percent of transit passenger miles. Vanpool growth during this period was 10.7 percent per year, but vanpools still accounted for only 2.0 percent of all transit passenger miles.

- Urban transit operators reported 10.4 billion unlinked passenger trips on 4.0 billion vehicle revenue miles. Rural transit operators reported an additional 124 million unlinked passenger trips and 558 million vehicle revenue miles.

Bus, Rail, and Demand Response: Transit Modes

Public transportation is provided by several different types of vehicles that are used in different operational modes. The most common is fixed-route bus service, which uses different sizes of rubber-tired buses that run on scheduled routes. Commuter bus service is similar, but uses over-the-road buses and runs longer distances between stops. Bus rapid transit is high-frequency bus service that emulates light rail service. Públicos and jitneys are small, owner-operated buses or vans that operate on less-formal schedules along regular routes.

Larger urban areas often are served by one or more varieties of fixed-guideway (rail) service. These include heavy rail (often running in subway tunnels), which is characterized primarily by third-rail electric power and exclusive dedicated guideway. Extended urban areas might have commuter rail, which often shares track with freight trains and usually uses overhead electric power (but might also use diesel power). Light rail systems are common in large and medium-sized urban areas; they feature overhead electric power and run on track that is partially or entirely on city streets shared with pedestrian and automobile traffic. Streetcars are small light rail systems, typically with only one or two cars per train that usually run in mixed traffic. Hybrid rail, previously reported as light rail and commuter rail, is a mode with shared characteristics of these two modes. The average station density (stations per track mileage) for hybrid rail is greater than for commuter rail and lower than for light rail, and unlike commuter rail, it has smaller peak-to-base ratio. Cable cars, trolley buses, monorail, and automated guideway systems are less-common rail variants.

Demand-response transit service is usually provided by vans, taxicabs, or small buses dispatched to pick up passengers upon request. This mode is primarily used to provide paratransit service as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act. Demand-response transit does not follow a fixed schedule or route.

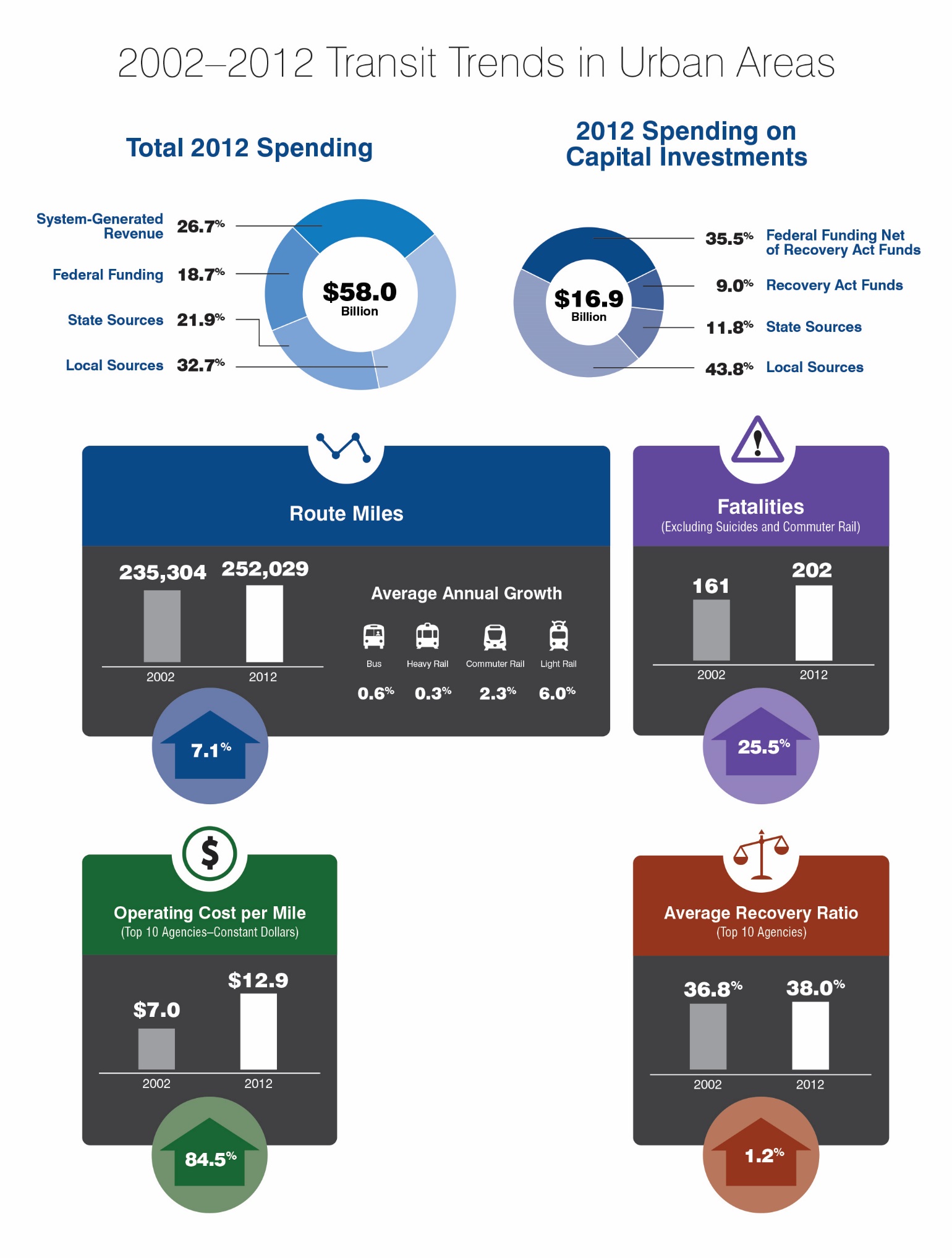

Spending on the System

- All levels of government spent a combined $58 billion to provide public transportation and maintain transit infrastructure. Of this, 26.7 percent was system-generated revenue, most of which came from passenger fares. The Federal government was the source of 19 percent of revenues, while the remaining funds came from State and local sources.

- Public transit agencies spent $16.9 billion on capital investments in 2012. Annually authorized Federal funding comprised 36 percent of these capital expenditures. Funds from the Federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act provided another 9 percent .

- Federal funding is primarily targeted toward capital assistance; however, Federal funding for operating expenses at public transportation agencies has increased from 19 percent of all Federal funding in 2002 to 35 percent in 2012. Virtually all of the increase is due to the 2004 change that made "preventive maintenance" eligible for reimbursement from section 5307 grant funds. Meanwhile, farebox recovery ratios, representing the share of operating expenses that come from passenger fares, have remained close to the 2000 value of 35.5 percent throughout this period.

Federal Transit Funding Urban and Rural

Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Urbanized Area Formula Funds are apportioned to urbanized areas (UZAs), as defined by the Census Bureau. UZAs in this report were defined by the 2000 census. Data from the 2010 census was used starting in the 2013 apportionment. Each UZA has a designated recipient for the Federal funds, usually a metropolitan planning organization or large transit agency, which then reallocates those funds in its area according to local policy. In small urban and rural areas, FTA apportions funds to the State, which allocates them according to State policy. Indian Tribes are apportioned their formula funds directly, once they are obligated in a grant. All funds then become available, on a reimbursement basis, through application to FTA.

Conditions and Performance of the System

Transit Remains Safe despite High Increase in Fatalities in 2012

- The number of fatalities from 2002 to 2011 (excluding suicides and commuter rail) remained stable, hovering around 150 fatalities per year. In 2012, however, fatalities significantly increased to 202 fatalities. In 2012, one in four transit-related fatalities was classified as a suicide. In 2002, the rate was just 1 in 13. The rate of suicides on transit facilities has increased every year since 2005.

Some Aspects of System Performance Have Improved

- From 2002 to 2012, transit agencies have provided substantially more service. The annual rate of growth in route miles ranged from 0.3 percent per year for heavy rail to 6.2 percent per year for light rail. This growth has resulted in 32 percent more route miles available to the public.

- From 2004 to 2012, the number of annual service miles per vehicle (vehicle productivity) remained unchanged and the average number of miles between breakdowns (mean distance between failures) increased by 24 percent .

- Growth in service offered was nearly in accordance with growth in service consumed. In spite of steady growth in route miles and revenue miles, average vehicle occupancy levels did not decrease. Passenger miles traveled grew at a 1.6-percent annual pace, while the number of trips grew 1.3 percent annually. This growth rate is significantly higher than the annual growth rate in the U.S. population during this period (0.93 percent ), which suggests that transit has been able to attract riders who previously used other modes of travel. Increased availability of transit service has undoubtedly been a factor in this success.

Unlinked Passenger Trips, Passenger Miles, Route Miles, and Revenue Miles

Unlinked passenger trips (UPT), also called boardings, count every time a person gets on an in-service transit vehicle. Each transfer to a new vehicle or route is considered another unlinked trip, so a person's commute to work could count as more than one trip if that person transferred between routes.

Passenger miles traveled (PMT) simply count how many miles a person travels. UPT and PMT are both commonly used measures of transit service consumed.

Directional route miles (DRM) measure the number of miles of transit route available to customers. They are directional because each direction counts separately; thus, a 1-mile-out and 1-mile-back bus route would be 2 DRM. Vehicle revenue miles count the miles of revenue service and are typically much greater than DRM because many trips are taken over each route (and each DRM). These measures are commonly used to describe the transit service provided.

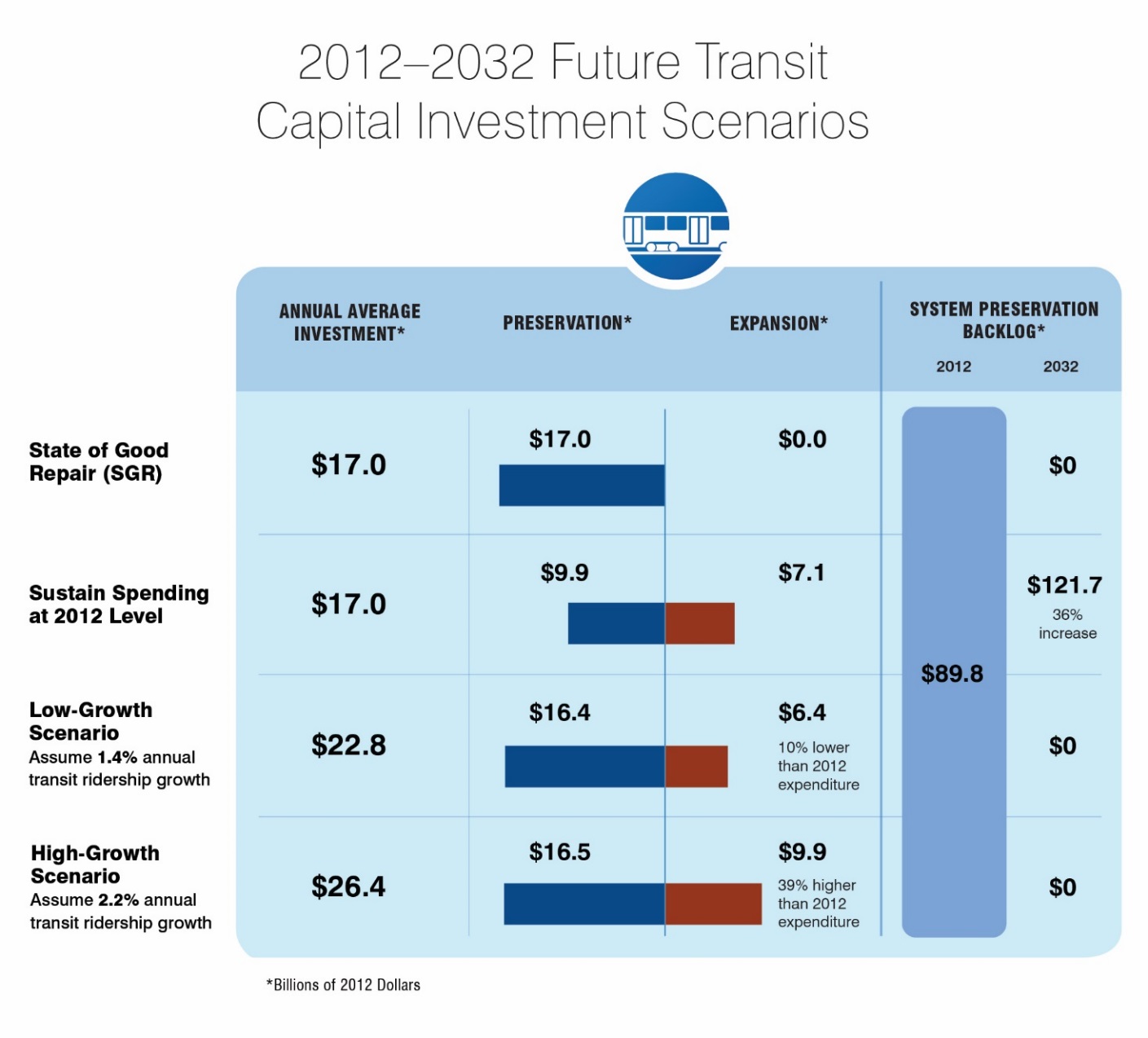

Future Capital Investment Scenarios — Systemwide

As in the highway discussion, the transit investment scenarios that follow pertain to spending by all levels of government combined for the 20-year period from 2012 to 2032 (reflecting the impacts of spending from 2013 through 2033); the funding levels associated with all analyses are stated in constant 2012 dollars. Unlike the highway scenarios, these transit scenarios assume an immediate jump to a higher (or lower) investment level that is maintained in constant-dollar terms throughout the analysis period.

Included in this section for comparison purposes is an assessment of the investment level needed to replace all assets that are currently past their useful life or that will be over the forecast period. This investment level would be necessary to achieve and maintain a state of good repair but would not address any increases in demand during that period. Although not realistic, this scenario does provide a benchmark for infrastructure preservation.

Sustain 2012 Spending Scenario

- The Sustain 2012 Spending scenario assumes that capital spending by all levels of government is sustained in constant-dollar terms at the 2012 level ($16.8 billion systemwide), including Recovery Act funds, through 2032. Assuming that the current split between expansion and preservation investments is maintained, this scenario will allow enough expansion to meet medium growth expectations but will fall far short of meeting system preservation needs. By 2032, this scenario would result in roughly $122 billion in deferred system preservation projects.

Low-Growth Scenario

- The Low-Growth scenario assumes that transit ridership will grow at an annual rate of 1.3 percent between 2012 and 2032. During that period, this scenario also attempts to pay down the current $89.8-billion system preservation backlog. The annualized cost of this scenario is $22.9 billion. In 2012, all levels of government spent a combined $16.8 billion for transit capital improvements.

High-Growth Scenario

- The High-Growth scenario assumes that transit ridership will grow at an annual rate of 2.2 percent between 2012 and 2032. This scenario also attempts to pay down the current $89.8billion system preservation backlog (subject to the same cost-benefit constraint). The annualized cost of this scenario is $26.4 billion.

State of Good Repair — Expansion vs. Preservation

As used in this report, the term "state of good repair" means that all transit capital assets are within their average service life. This general construct enables FTA to estimate system preservation needs. The analysis examines the age of all transit assets and adds the value of those that are past the age at which that type of asset is usually replaced to a total reinvestment needs estimate. Some assets can continue to provide reliable service well past the average replacement age and others will not; over the large number of assets nationally, the differences average out. Some assets will need require replacement, and some will be refurbished. Both types of cost are included in the reinvestment total. State of good repair is a measure of system preservation needs, which failure to meet will increase operating costs and poor service.

Expansion needs are treated separately in this analysis. They result from the need to add vehicles and route miles to accommodate more riders. Estimates of future demand are inherently speculative. Failure to meet expansion needs results in crowded vehicles and represents a lost opportunity to provide the benefits of transit to a wider customer base.