U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

This chapter addresses the high-level design of a traffic monitoring program and how data business planning can be used to support the design and development of the program at State highway agencies. It provides guidance on designing a traffic monitoring program and explains the importance of having such a program from three perspectives: statewide, regional/sub-area, and roadway facility/corridor-specific traffic monitoring. It also describes recommendations for a traffic program evaluation to be conducted by States every five years. More detail regarding guidance and examples of traffic monitoring programs are provided in Chapter 3 and the Appendices.

Many transportation agencies have recognized that traffic data programs support a growing variety of functions and critical decision processes within their agencies. The need for data and the benefits that result from the required data must be balanced against available and potential resources to implement an effective and efficient traffic monitoring program.

Therefore, in planning and designing a traffic monitoring program it is critical to consider one’s customer needs and the benefits that result from the timely delivery of quality traffic data for decision support. The customers of traffic data programs generally fall into the following categories:

The components of traffic data programs include planning, design, calibration, collection, distribution, analysis, reporting, and maintenance. Uses of traffic data include project and resource allocation programming; performance reporting; operations and emergency evacuation; capacity and congestion analysis; traffic forecasts; project evaluation; pavement design; safety analyses; emissions analysis; cost allocation studies; estimating the economic benefits of highways; preparing vehicle size and weight enforcement plans; freight movement activities; pavement and bridge management systems; and signal warrants, air quality conformity analysis, etc.

The following table is a useful resource detailing some of the uses of traffic data collection that includes traffic counting, vehicle classification, vehicle weighing, and speed monitoring.

| Highway Activity | Traffic Counting | Vehicle Classification | Vehicle Weighing | Speed Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design |

|

|

|

|

| Engineering Economics |

|

|

|

|

| Finance |

|

|

|

|

| Legislation |

|

|

|

|

| Maintenance |

|

|

|

|

| Operations |

|

|

|

|

| Planning |

|

|

|

|

| Environmental Analysis |

|

|

|

|

| Safety |

|

|

|

|

| Statistics |

|

|

|

|

| Private Sector |

|

|

|

|

| Administration, Other |

|

|

|

The TMG is designed to provide guidance to States, MPOs and local agencies in establishing and maintaining a traffic monitoring program. Other national reference material includes the AASHTO Guidelines for Traffic Programs and the ASTM Loop Detector Handbook. Many States have developed their own statewide versions of traffic monitoring guidelines including Florida, California, and Texas (Appendix D, Case Study 1).

The following text describes the purpose and framework for establishing a traffic monitoring program. These programs are designed to collect traffic data and monitor travel within a defined geographic area for a State, region, or at the roadway-specific level. The types of data collected primarily consist of volume, classification, weight, and speed data. Many traffic programs are also adding bicycle and pedestrian counting. In the TMG, motorized programs include traditional traffic and non-motorized refers to bicycle and pedestrian counting programs. Chapter 4 is dedicated to guidance on bicycle and pedestrian counting.

A traffic monitoring program is important from a statewide perspective to meet Federal and State requirements and is used to monitor travel primarily on State system roads. Traditionally, statewide traffic monitoring programs were designed to collect primarily three types of data: volume, classification, and weight. Speed data has now been included to address the need for data related to travel times and to determine the impact of speed on traveler safety. Each type of data can be used for many purposes, including tracking traffic volume trends on important roadway segments; providing input to traffic management and traveler information systems; determining truck travel patterns; providing input for safety and design studies along with roadway performance monitoring; and for providing data for programs such as the Highway Performance Monitoring System (HPMS). Traffic data reported to FHWA is used to apportion funding to States from the U.S. Highway Trust Fund. Proper support and funding of traffic counting programs is critical to ensure the State data collection remains up to date and is providing the best possible data.

The information obtained from statewide traffic monitoring programs is also the primary information resource for almost all general queries about road use in a State. Many users, both inside and outside of State highway agencies, periodically need basic traffic statistics, and those statistics should be readily available and comparable throughout the State. The statewide traffic monitoring program is responsible for collecting and providing that information. Requests for statewide data can range from how vehicle miles of travel are changing in order to compute carbon emissions to whether specific roads carry enough volume to warrant new retail construction activity. Having a strong statewide counting program allows an agency to answer a wide range of key policy and business questions confidently and effectively. Roadway agencies that cannot provide direct, timely, and accurate answers to these basic queries risk losing their credibility and subsequently the support of decision makers and the taxpaying public.

Traffic counts are fundamental to almost every task a highway agency performs and critical to a comprehensive performance measurement system. The timely delivery of high quality data can serve as a critical framework for effective decision making. The ability to describe how much traffic is using a road reflects positively on the agency’s ability to effectively perform its responsibilities and manage its budget. Consequently, collecting, summarizing, using, and reporting this data is a critical task for any roadway agency, delivering more relevant and cost effective data for operations, construction, and maintenance decisions and planning with benefits across the transportation system. Additional information with an example of the design of a statewide traffic monitoring program is found in Appendix D.

The measurement of traffic volumes and its composition (class, weight, speed) is one of the most basic functions of highway planning and management. Traffic volume counts are the most common measure of roadway use and count data is needed as input to nearly all traffic engineering analyses. While several traffic volume statistics are used in traffic analyses, of primary interest for the design of statewide traffic monitoring programs are annual average daily traffic (AADT) and average daily vehicle distance traveled (DVDT). Because DVDT is computed by multiplying the roadway segment AADT by the length of that segment, the primary goal of most traffic monitoring programs is to develop accurate AADT estimates, which can then be expanded to estimates of travel.

The recommended framework for a traffic monitoring program consists of two basic components:

1. Continuous counts (temporal); and

2. Short-duration counts (spatial) including periodic coverage counts and special needs counts.

All highway agencies should have access to data collected from continuous counters. Agencies should work with each other to ensure that enough data is collected and shared to allow calculation of accurate adjustment factors needed to convert short-duration traffic counts into estimates of AADT. Chapter 3 in the TMG provides considerable guidance on how to structure continuous count programs, how to determine the appropriate number of counters for adjustment factor development, and how to apply those factors.

The continuous counts help the agency understand temporal (time-of-day, DOW, month-of-year and multi-year) changes in traffic volume, speed, class, and weight and allow development of the mechanism needed to convert short-duration counts into accurate estimates of annual conditions. Adjustments to short-duration count data are normally required to remove temporal bias from data used for AADT computation.

Highway agencies perform short-duration counts for a variety of purposes including meeting Federal reporting needs (HPMS), supplying information for individual projects (pavement design, planning studies, etc.), and providing broad knowledge of roadway use. The portable short-duration counts also ensure geographic diversity and coverage. The short-duration counting program is most efficient if these various data collection efforts are coordinated so that one count program meets multiple needs. Examples of coordination include: sharing counting schedules with city/county/MPO staff; putting technology solutions in place that include access to software that encourages the integration/dissemination/conversion of schedules/data collected from city/county/MPO and State agencies; and establishing a data governance committee that crosses agency jurisdictions including national, State, county, city, and MPO boundaries.

The two types of short duration counts are described in the following sections.

The coverage count subset covers the roadway system on a periodic basis to meet both point-specific and area needs, including the HPMS reporting requirements. The TMG recommends that the short-count data collection consist of a periodic comprehensive coverage program over the entire system on a maximum six-year cycle. The coverage plan includes counting the HPMS sample and full-extent sections on a shorter (maximum) three-year cycle to meet the national HPMS requirement.

The coverage program is supplemented with a special needs element where additional counts are performed as needed to meet other more specific data needs. The special needs program represents many different operations and may include the following:

The specific requirements (what is collected, when and where it must be collected) for these and other special needs studies vary from agency to agency. The ways in which agencies balance the benefits and costs of addressing these all-encompassing needs against their limited traffic counting budgets lead to the very different data collection programs that exist around the country.

Vehicle classification data is a critical component of a well-designed traffic monitoring program because substantial amounts of classification data are needed to understand motorcycle, bus, and truck travel on highways. To address the need for classification data, the TMG recommends a coverage program structure for both volume and vehicle classification programs. More detail is provided in Chapter 3.

A traffic monitoring program is used at the regional and sub-area level to address information needs on roads that are not met as part of a general statewide program. Traffic monitoring at this level is generally more detailed than the statewide program, and may include roads that are not part of the statewide program.

Regional or sub-area monitoring plans are generally designed to answer specific questions of regional importance. They often provide additional detail on traffic movements that cross-jurisdictional borders (e.g., they may provide data that are used to allocate State resources between jurisdictions within the region), or provide data needed to answer key scoping questions for upcoming regional projects. For example, urban areas often collect congestion and travel time reliability data. Similarly, geographic areas that depend on recreational traffic movements often collect data in different ways or times than would otherwise be collected for general State traffic monitoring purposes. Detailed regional traffic counts can be vital to maintaining or improving the economic vitality of communities that depend on recreational movements. Additional information with an example of the design of a regional traffic monitoring program is found in Appendix D, Case Study 4.

Facility-specific monitoring plans are the most detailed level of the three types of traffic monitoring programs. Roadway facility-level monitoring provides data needed at the project level. A minimum of four data items are typically produced as part of these monitoring efforts: AADT, K-Factor, D-Factor, and truck percentages. However, monitoring efforts may also collect data items that are needed for specific project purposes such as vehicle speed distributions and turning movements.

Facility-specific traffic monitoring programs are designed to provide the site-specific traffic statistics needed for roadway improvement and planning studies. They are also used to collect the detailed data needed to design, implement, and refine traffic operations plans (e.g., traffic signal timing or event planning). Well-designed facility monitoring plans are fundamental to the effective management and operation of heavily used roadways.

It is in a DOT agency’s best interest to strategically conduct a comprehensive evaluation of their traffic monitoring program at a minimum of once every five years. This comprehensive evaluation should include all aspects of the program including equipment inventories, site selection procedures, data collection practices, validation, quality control, analyzing data, and data dissemination practices. A comprehensive travel monitoring program evaluation should provide an agency with a strategic business plan that documents program strengths and deficiencies with targeted recommendations for minimizing deficiencies and leveraging data program assets for a broad range of agency needs. A comprehensive program evaluation is recommended every five years because travel monitoring equipment and technology, as well as Federal regulations requiring travel monitoring data, can change over time, ultimately requiring travel monitoring program changes.

Conducting a program evaluation can benefit a DOT agency by saving the agency time, resources, and money by implementing newly recommended business practices that eliminate unnecessary or inefficient processes or data management practices. Examples include (but are not limited to) the following:

Many agencies already rely on obtaining advice from partner Federal, State, and local agencies related to budgeting, monitoring equipment, resource allocations, etc. When conducting a comprehensive program evaluation a similar industry practice is advised.

Managing a travel monitoring program requires many different skills including budgeting; resource allocations; statistical analyses and quality evaluation of the travel monitoring program’s data. The travel monitoring program industry currently lacks the ability to evaluate and rank data programs based on a national standardized performance matrix. Although the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has the ability to evaluate continuous count programs by the number and quality of continuous count station data by State, currently there are no metrics for other travel monitoring program aspects such as short-duration counts programs, weigh-in-motion, etc. The remainder of this section describes the steps for conducting the program evaluation.

The program evaluation review should include the following elements.

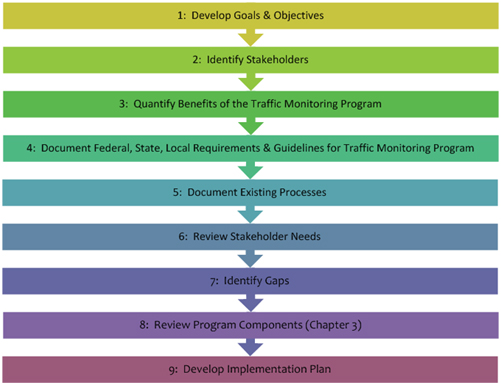

1. Goals and Objectives – Identify a clear statement of goals and objectives of the traffic monitoring program and how it fits into the planning process at the agency, and supports other agency needs.

2. Stakeholders – Identify all stakeholders and customers of the data. Customers of the traffic data program should include internal customers, external partners (MPOs, local governments and the public) and FHWA (for reporting purposes). The stakeholders should include both data collectors and users. (See Appendix D.)

3. Benefits of the Traffic Monitoring Program – Document the benefits of a traffic monitoring program for a State transportation agency and all of the internal and external stakeholders. This can include fiscal decision-making abilities and resource benefits.

4. Documentation of Federal, State, Local Requirements and Guidelines for Traffic Monitoring Program – Document any Federal, State, and local requirements and guidelines that must/should be followed in establishing traffic monitoring programs. Federal guidelines are contained in the TMG. State-specific requirements should be documented separately. In some States, a manual or handbook documenting existing State traffic program equipment and resources is also developed.

5. Documentation of Existing Processes – Document the physical infrastructure of existing data programs. This documentation serves as customer data supply and demand documentation helping all stakeholders including the managers, the collection staff, analysts, and customers of the statewide traffic database. Some States apply use-case diagrams or other forms of diagramming and flowcharting to indicate which data elements are collected, how they are processed, analyzed and reported, who is involved, and which databases are integrated and published. Staffing responsibilities should also be documented for future planning.

This documentation is extremely important in succession planning. It should (minimally) include the following elements:

6. Review of Stakeholder Needs – This review can be accomplished through surveys, informal discussions, meetings, or focus groups. The objective is to determine stakeholder needs (data demand) with respect to the following dimensions of traffic data quality (data supply):

7.Identification of Gaps – Includes a review of resources and allocation of resources to priorities, identification of gaps, and overlaps in the data program. These can include the number of collection devices, processes, data gaps, and resources. For example, a State may identify that the factor groups they are using are not adequate, or there may be a need to add more ramp counts. Other gaps could include the need for more or different report formats. An example of an overlap may be the identification of an opportunity to share traffic data with a local agency or duplicated count locations. The key in this step is to document all needs and carefully prioritize them against available or potential resources. This step allows for the provision of expectations regarding needs and a vision of the State’s future traffic monitoring programs.

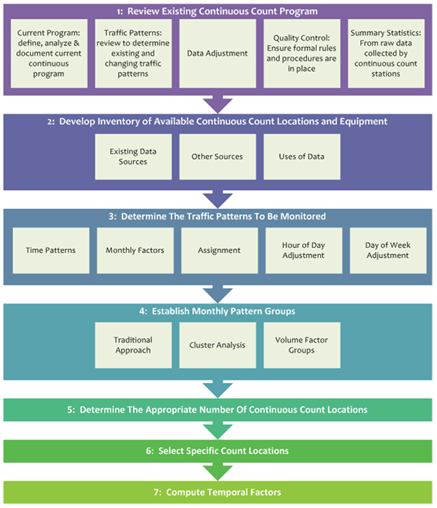

8.Review Program Components – Chapter 3 of the TMG contains specific guidance related to traffic data programs. During the program evaluation (recommended at least every five years) States should review all steps documented to determine if they are meeting the requirements. The figures in Chapter 3 outlining steps for establishing elements of traffic data programs will be particularly useful in the assessment (Steps for Establishing a Continuous Data Program, Steps For Creating and Maintaining a Continuous Data Collection Program, and Steps for Creating and Maintaining a Continuous Data Program).

Source: Federal Highway Administration.

9.Implementation Plan – Develop an implementation plan to make the improvements identified in Step 7 and deemed necessary in Step 8. In documenting improvement needs, the traffic monitoring staff may wish to conduct a benefits analysis and risk assessment. This assessment would involve identifying the benefits accruing from traffic monitoring program data and products, and the risks of not providing the traffic data at the desired level of quality. More information related to risk assessment and corresponding risk management programs can be found in NCHRP Report 666: Target-Setting Methods and Data Management to Support Performance-Based Resource Allocation by Transportation Agencies, Volume II, and in Assessing the Value of the ADOT&PF Data Programs White Paper, September 2009. These steps are illustrated in Figure 2-2.

Source: Federal Highway Administration

This business process review should be updated annually to ensure the optimum use of resources with respect to stakeholder needs. States have embarked on business process reviews to document their processes, identify gaps, and improve their traffic monitoring programs. Good examples are provided in Appendix K for Georgia DOT and Colorado DOT.

Data Business Planning is an important component of any State DOT traffic monitoring program because it ensures that customer needs are met and the most efficient methods are deployed. It also provides accountability, transparency, and other strategic management benefits such as answering “what does your data program staff do?” Several States including Texas, Florida, Colorado, Virginia and Ohio have well-documented programs and can be used as references (see Appendices D, E, and K).

This section recommends best practices in coordinating count programs between State highway agencies and external agencies, and the methods used for sharing data.

Access to data collected from continuous counters is encouraged for all highway agencies. Considerable benefit can be obtained by sharing these data collection resources. Access to additional counts will provide data for quality assurance, filling of count gaps, saving money, and ease of reporting because all data can be integrated into one platform. On the other hand, the challenges to sharing data among agencies can be many, but are not insurmountable. For example, data may exist in different formats or be collected with different standards (e.g., 24-hour versus 48-hour counts). With carefully planned and implemented management strategies in place, (such as creating a data governance committee, implementing QA/QC data procedures, and having a scalable enterprise-wide data warehousing solution) an agency can not only overcome data sharing challenges, but benefit significantly through data sharing best practices.

Agencies should work together to reduce duplication in the number and location of permanent, continuous data collection devices. Agencies should share the data they collect (e.g., a State DOT could use monthly and DOW information collected at permanent sites operated by a county or city as part of developing adjustment factors for a specific urban area). A single count location can supply information for many purposes (e.g., permanent, continuous weigh-in-motion scales supply weight, classification, speed, and volume data). Opportunities to share data exist not only among agencies but also within agencies. Ensuring that planning, operations, maintenance, and construction groups share the data they collect can substantially increase the availability of traffic monitoring data and benefits derived, while reducing the overall cost of data collection.

A key source for urban traffic data is the traffic surveillance systems used for traffic management and control. The Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) program (see more information in Chapter 5) offers highway agencies the ability to collect continuous traffic monitoring data at high volume locations. Access to these data requires proactive efforts by the traffic monitoring groups, as archiving and analysis of surveillance data are traditionally less important to the operations groups that build, operate, and maintain these ITS systems. Without proactive efforts by the traffic monitoring groups, the benefits of ITS data can be lost because operations groups spend their scarce resources on operational improvements rather than on the archiving and analysis software needed to convert surveillance data into useful traffic statistics. Traffic monitoring assets can also supplement ITS assets and when configured appropriately can also provide critical information for operations.

Examples of best practices related to sharing traffic data can be found in Appendix D

This section describes the use of calibration procedures (explained more fully in Appendix F), the processing of data, and the use of compliance reviews to assess how well the State’s traffic monitoring program is performing in meeting MPO, State, and Federal requirements. This combination of tasks ensures that the traffic data collection equipment is working correctly, and that the data collected in the field is correctly processed to ensure that the summary statistics being reported accurately reflect the traffic conditions that are occurring on the roadway.

On-site and in-office calibration and tracking of site information should occur regularly (daily, monthly, and annually as needed). Having a robust traffic monitoring calibration program in place includes:

Calibration includes performing a variety of tests on equipment to ensure that it functions as intended and correctly collects, processes, and reports the traffic data. The calibration process can identify both major errors (such as failed sensors) and minor errors (such as errors in site set-up, or the wrong classification algorithm installed on a shipment of devices) that can result in the collecting, processing, storing, and disseminating of inaccurate traffic statistics. The entire traffic monitoring program credibility is at stake when erroneous data is collected, processed, stored and disseminated. To avoid the risk of producing and disseminating erroneous data, traffic data programs should calibrate often.

Errors associated with calibration inaccuracies significantly increase the cost and decrease the usability of data from the entire traffic monitoring program.

However, once the data have been physically collected, more work remains to be done. To convert data into published statistical information, an agency must process (integrate, convert, calculate, QA/QC, store, manage, and provide access, etc.) the data consistently and correctly. Correct and consistent data processing ensures that AADT estimates produced from a simple axle counter can be accurately compared with AADT estimates collected using a sophisticated vehicle classifier. Consistent processes also ensure that agency credibility which allows an agency to easily defend their reported statistics and show through transparent audit processes that their data accurately reflect current traffic conditions. This allows States to pass Federal compliance reviews used to ensure that reported VMT statistics, a key variable used in funding allocation, are being accurately reported, and assures decision-makers the data deliverables are appropriate for critical decisions.

Data quality assurance processes are a critical component of any well-designed traffic monitoring program. The TMG recommends that each agency improve the quality of reported traffic data by establishing quality assurance processes for traffic data collection and processing. Each highway agency should have formal, documented rules and procedures for their quality control efforts.

The Data Quality Act (DQA) directs the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to issue government-wide guidelines that provide policy and procedural guidance to Federal agencies for ensuring and maximizing the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of information (including statistical information) disseminated by Federal agencies.

A comprehensive and quality documented process will also assist in a smooth succession when there is turnover in staff.

Another critical factor of a well-designed traffic monitoring program is thorough and complete documentation. States are encouraged to maintain adequate documentation to support the decisions made and to allow future reexamination of those decisions as experience is gained in such areas as the factoring process. Documentation, such as the HPMS annual report which includes a requirement for reporting of metadata pertaining particularly to traffic and pavement data, is also recommended for any processes or methods used in data collection and analysis that may affect the outcome of the traffic data reported.

Metadata is documentation used to describe specific data items and datasets. HPMS recommends reporting of metadata that contains data that captures and explains variability in the collection and reporting of traffic (and pavement) data. For example, the traffic metadata may be used to describe if AADT values have been seasonally adjusted, if AADT values are directly (raw unadjusted data) from vehicle count data, or if AADT is adjusted by annual growth/change.

NCHRP Report 666: Target-Setting Methods and Data Management to Support Performance-Based Resource Allocation by Transportation Agencies also explains that it is becoming more common for documentation of data programs to be a shared responsibility between IT divisions and business units within the organization. The business units have a responsibility to document the business needs and benefits for the traffic programs so that executives internally, as well as external entities such as legislatures, are aware of the importance of continued funding and resource allocation to support these critical programs. Establishing structured documentation procedures includes having well defined change tracking mechanisms to ensure that the prioritization of requested system changes is in accordance with the primary goals and objectives of the agency (NCHRP 666, 2010).

All types of documentation that are used to support traffic monitoring programs become a significant part of the repository of information about the program. This important information can be used at the national level for modeling travel trends, conducting highway safety and weight studies, as well as supporting State needs and uses for the data. Appendix D contains an example case study from Texas that demonstrates the importance of documentation in supporting its statewide traffic monitoring program.