Appendix E: Best Practices

Throughout the completion of this report, the U.S. DOT identified many lessons learned and best practices in the Gulf Coast States and beyond using the plan evaluations, State visits, and literature search as resources. In this appendix, the U.S. DOT has expanded upon some of the best practices that were found.

While the wide variety of best practices range from a technology solution to a Governor's Executive Order, they do share one commonality — the recognition that the plans and tools used to execute evacuations need to be revised to maintain their effectiveness. In all of these examples, there is an underlying belief that the public can always be served better.

Texas Task Force Addresses Concerns About Decision Making and Management and Other Important Issues

The Texas Task Force on Evacuation, Transportation, and Logistics was established in direct response to the evacuation concerns brought on by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita during the Fall of 2005. Texas Governor Rick Perry, Houston Mayor Bill White, and Harris County Judge Robert Eckels established the Task Force to improve evacuation procedures for major cities in Texas. In a September 30, 2005 press release from the Office of the Governor, Governor Rick Perry stated, "This task force brings together some of the best and brightest minds in transportation, energy, academia and government who will help all levels of government learn from the experiences of Rita and establish better evacuation plans for future emergencies." With the increased attention on the Gulf Coast States, events took place that defined lessons learned and recommendations to better address evacuations.

To gather information for its final report, the Task Force held public hearings almost once a week from October 25, 2005 until December 13, 2005. During the public hearings, the Task Force invited State and local officials and additional stakeholders including evacuees, school officials, charitable organizations, relief workers, hospitals, medical personnel, individuals with special needs, and their caregivers. The Task Force also offered citizens the opportunity to give testimonies. Meeting locations varied in Texas cities such as Houston, Fort Worth, Corpus Christi, South Padre, San Antonio, and Beaumont.

The final Task Force report was released on February 14, 2006, and included the following key areas that were the items most often addressed during the public hearings. Each area included a narrative on concerns, findings, and recommendations.

- Command, control, and communication

- Evacuation of people with special needs

- Fuel availability

- Flow of traffic

- Public awareness.

As a result of the final report recommendations, Texas Governor Rick Perry issued the Executive Order RP57 on March 21, 2006. This executive order has led to the implementation of some of the Texas Task Force recommendations that were included in the final report. The executive order instructs respective offices and officials on their roles and responsibilities regarding the recommendations being enacted. It provides that the State Director of Homeland Security will ensure the executive order is carried out consistent with the final report and recommendations of the Texas Task Force.

Command, Control, and Communications

The Emergency Management Directors including county judges and mayors within each of the state's 24 Council of Governments will be responsible for establishing a Regional Unified Command Structure (RUCS). Each region will have an Incident Commander that will be the point of contact within the region during the disaster response, including mass evacuation. As stated by the Executive Order, each RUCS will be established by April 18, 2006. Also, the name of a person and qualifications of the Incident Commander should go to the Governor's Division of Emergency Management by April 20, 2006. The Texas Department of Public Safety will be the lead in command, control, and communications and other operational tasks, as directed by the Governor, during evacuations and other disaster response operations that involve multiple RUCSs.

The Executive Order also cites many tasks for the Governor's Division of Emergency Management including:

- Creating eight Regional Response Teams (RRTs) to support multi-jurisdictional operations.

- Developing a statewide hurricane evacuation and shelter plan.

- Overseeing the implementation of regional responses and evacuation plans within the State.

- Coordinating with independent school districts and public colleges, universities, and the university system to provide transportation and facilities to support the execution of state and local evacuation and shelter plans. (In addition, the Governor's Division of Emergency Management will develop policies for reimbursement to school districts and public colleges, universities, and university systems for evacuation, shelter and transportation expenses.)

- Leading and directing annual hurricane evacuation exercises.

Evacuation of People with Special Needs

The Governor's Division of Emergency Management will coordinate with the Department of State Health and Human Services, the Department of Aging and Disability Services, the Governor's Committee on People with Disabilities, and other state agencies to define special needs and develop an evacuation and shelter plan that supports the requirements of the people with special needs. The above agencies, along with appropriate stakeholder groups, will work to develop criteria for the evacuation plans for special needs facilities, including both licensed and unlicensed facilities. The plan will also address the special needs population and the evacuation and sheltering needs of their service animals.

Additional tasks for the Governor's Division of Emergency Management include:

- Ensuring local jurisdictions and RUCSs approve evacuation plans maintained by special needs facilities.

- Developing and implementing a statewide database to assist in the evacuation of people with special needs, especially jurisdictions on the coast having priority. Each RUCS will be responsible for collecting and providing information for the database.

Fuel Availability and Distribution

The Texas Department of Transportation will coordinate with the Texas Oil and Gas Association and other industry partners to develop a plan to address fuel availability along major evacuation routes and establish a fuel operations function in the State Operations Center to coordinate the distribution of fuel prior to and during evacuations.

- Tasks for the Governor's Division of Emergency Management include:

- Working with local officials to develop evacuation plans that address fuel availability during an evacuation

- Establishing fuel procedures for distribution during an emergency like an evacuation

- Developing policies and procedures at the Division of Emergency Management to reimburse local governments and other support entities for evacuation fuel-related expenses in the event that the Texas Legislature or United States Congress designates funding for that purpose.

Traffic Control and Management

The Texas Department of Public Safety will oversee traffic management of the evacuation routes during multi-jurisdictional evacuations. Also, the Texas Department of Public Safety, in coordination with the Department of Homeland Security and the United States Customs and Border Patrol, is taking steps to expedite the flow of traffic through checkpoints on major hurricane evacuation routes and assist in the development of traffic management plans to accommodate mass populations at checkpoints.

Tasks for the Texas Department of Transportation include:

- Coordinating with the Texas Department of Public Safety to develop contraflow plans for major hurricane routes that were identified by the Texas Task Force final report

- Implementing short- and long-term solutions to reduce congestion on the one-lane section of the U.S. Highway 290 at Brenham, Texas, during evacuations.

- Starting the implementation of the infrastructure projects recommended in the March 2005 report to the Governor on Texas Hurricane Preparedness. (The report addresses the obstructions on evacuation routes during mass evacuations.)

Public Awareness

The Public Utility Commission is to work with utility companies that are regulated by the Commission and serve counties in hurricane evacuation zones to include hurricane preparedness and evacuation-related public awareness information in monthly billing statements prior to and during the hurricane season each year.

Additional Sources

The following documents and resources were used to research this best practice:

- Executive Order RP57 on implementing recommendations from the Governor's Task Force on Evacuation, Transportation, and Logistics. March 21, 2006. http://www.governor.state.Texas.us/divisions/press/exorders/rp57/view.

- Governor's Task Force on Evacuation, Transportation and Logistics Final Report to the Governor. February 14, 2006. http://www.governor.state.Texas.us/divisions/press/files/EvacuationTaskForceReport.pdf.

- Berger, Eric. "Houston Area Must Quickly Pick Disaster Command." The Houston Chronicle. March 22, 2006. http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/front/3739709.html.

- Hughes, Polly Ross. "Heat Is on to Improve Plans for Evacuations." The Houston Chronicle. March 25, 2006. http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/metropolitan/3747550.html.

Mississippi and North Carolina Departments of Health Collaborate on After-Action Report

A key component of the planning process is the completion of after-action reports. The purpose of after-action reports is to document the significant outcomes following a major event or exercise, and then integrate the findings into emergency management plans and standard operating procedures so that the problems encountered are mitigated during future response. All levels of government, nonprofit organizations, and the private sector engage in the after-action process.

In addition to the after-action reporting carried out by the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency (MEMA), lead agencies for annexes to the State's emergency management plan are in the process of finalizing their own after-action reports. One example is the Mississippi Department of Transportation (MDOT). Although its final report has not been released yet, MDOT has already identified the need to manage its fuel resources during all stages of a disaster more efficiently and effectively. As a result, MDOT will likely procure advanced reserves. MDOT is also reviewing how it works with the MEMA emergency operations centers as well as it own. MDOT typically produces an after-action report following every hurricane season. The after-action report for 2005 is even more important since Katrina has changed the transportation landscape, creating situations that State officials have not had to deal with in the past.

One challenge of developing an after-action report is balancing the subjectivity. Often, reviews are limited to internal sources, avoiding the risk that an outside expert may not be able to fully understand what occurred during the disaster. Ideally, there would be a peer review system. The Mississippi Department of Health (MDOH) and North Carolina Office of Emergency Services (OEMS) are in the process of developing a peer review system for the ESF-8: Public Health and Medical Services after-action report.

Mississippi and North Carolina have a history of exchanging resources during disasters. For instance, the North Carolina Department of Health deployed 458 healthcare professionals to its field hospital in Waveland, Mississippi, following Hurricane Katrina through the EMAC system. North Carolina met other requests for assistance in Mississippi and Louisiana as well. This put North Carolina in a position to review the execution of Mississippi's ESF-8 since North Carolina's own resources were on the ground during the event, and the staff already understood the after-action report process from experiences in their own State. The OEMS also leveraged partnerships with Duke University, the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (UNC-CH), and several other North Carolina State agencies to conduct an in-depth analysis of what happened to Mississippi's sheltering system after the storm. In the coming weeks, an after-action report will be released with findings and recommendations that will be much more detailed than MDOH could have done on its own. Mississippi's ability to provide sheltering assistance to its residents will be greatly improved as well.

Not only is OEMS's review of MDOH's actions during Hurricane Katrina an opportunity for exchange at the professional level, it is an example of how States continued to share their resources long after the event has passed. Throughout the after-action report process, MDOH has only been responsible for the travel costs for North Carolina officials and researchers to come to Mississippi. North Carolina's State agencies participating in this process pay the salaries and other expenses for its staff members. Rather than viewing this as an additional cost, the North Carolina OEMS and its partners saw it as an opportunity to explore their own roles and responsibilities during a catastrophic event and review their own plan while promoting "win-win" collaboration at the State level.

This after-action report project also demonstrates the number of organizations that could be involved in post-event analysis. For instance, the list of agencies that the North Carolina OEMS led during the past few months includes, but is not limited to:

- North Carolina Division of Emergency Management, Public Health Preparedness and Response

- Department of Environmental and Natural Resources, Division of Facility Services

- Office of Emergency Medical Services

- Public Health Regional Surveillance Teams from Forsyth and Cumberland Counties

- Office of Citizens Services

- Hospitals, including the State Medical Assistance Team Commander from Duke University

- EMS systems

- State Medical Examiners Office

- UNC-CH public health researchers.

Because of the in-depth level of analysis for the MDOH after-action report, MDOH has also worked independently of North Carolina's study to address some of the problems it encountered last summer. While, in some cases, preliminary findings may be released, MDOH wants to be sure that the findings are as objective as possible when the final report is released around June 1, 2006. MDOH intends to incorporate as many of the after-action report's recommendations as possible based on its ability to fund and implement them.

Some changes that MDOH is already working on in advance of the 2006 hurricane season include the designation of community colleges as shelters and the development of a partnership to improve the identification of the deceased. MDOH has reached out to community college presidents to pre-determine sites and buildings that could be used as special needs shelters. The goal is to place 100 to 120 special needs beds at each community college along with the requisite food, water, power supplies, and staff. The community colleges will also provide appropriately trained staff and students, including LPNs, RNs, and respiratory therapists, to serve at these new shelters.

Following Hurricane Katrina, MDOH felt the need to increase the speed of identification of the victims of the hurricane and its aftermath. While they were able to utilize the Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team through federal assistance, MDOH believes response can improve by partnering with the Mississippi Coroners' Association and the Mississippi Department of Public Safety's Bureau of Investigation. Currently, the State Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan (CEMP) appoints one person to be in charge of identification of the deceased. In the case of Katrina, this proved to be too much for one person. By sharing the responsibility among three organizations, MDOH hopes to improve the speed of identification and alleviate the burdens previously placed on a small group of people. These improvements combined with the recommendations from the after-action report should strengthen Mississippi's plan for sheltering in the coming years.

Contacts

The following individuals provided information that contributed to the development of this practice:

- Bob Chapman, Mississippi Department of Transportation

- Art Sharpe, Mississippi Department of Health

- Holli Hoffman, North Carolina Office of Emergency Medical Services.

Louisiana Organization Provides Public Education in 21 Parishes

The Terrebonne Parish Readiness and Assistance Coalition (TRAC) was born out of a call to action in response to Hurricane Andrew in 1992. As this community pulled together to help rebuild and raise homes for those in need, the founders of TRAC,28 community organizations including emergency management, religious groups, and hospitals partnered to prepare and educate area residents. Ninety percent of the parish is wetlands or covered by open water. Many of the people in the area are low income and have language barriers.

From that point forward, TRAC began developing community-specific outreach materials about preparedness and mitigation techniques. In 1998, TRAC received a Hazard Mitigation Grant from the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program through the Louisiana Office of Emergency Preparedness, allowing them to design hurricane preparedness campaigns in 13 southeast Louisiana parishes. This campaign included preparedness programs in local nursing homes, childcare centers, day camps, schools, Boy Scout troops, and church groups, as well as public service announcements (PSAs) broadcast on the radio and educational materials distributed through newspapers, hardware stores, and grocery stores.

Today, TRAC serves 21 parishes throughout southern Louisiana through a comprehensive public education campaign that includes print, television, radio, Web, and personal education and outreach. Updated in 2005 (prior to Hurricane Katrina), each part of the campaign reminds Louisiana residents that they must be prepared for hurricanes and corresponding evacuations.

|

TRAC's public education resources are quite extensive and have required a significant investment of financial resources over the past 14 years. Communities interested in providing at least some basic information about emergency preparedness, but unable to produce something as comprehensive as TRAC, should leverage resources like FEMA's Are You Ready guide and the Ready.gov brochure. Local communities, companies, and governments can download these resources and add their own logos and contact information for distribution to residents. If you live or work in southern Louisiana and would like to work with TRAC to reprint or distribute its materials, visit http://www.trac4la.com or call 877-TRAC-4-LA. |

Much of the information that TRAC provides its residents could be used as baseline information for other disasters and by people who live in other parts of the country. It does not differ significantly from publications like FEMA's Are You Ready guide. What TRAC does is convey the risks associated with hurricanes into the context of Louisianans' geography and attitudes. This includes describing the long history of devastation and destruction of hurricanes in the State, including the storm that hit Chenier Caminanda in 1893 and Hurricane Betsy in 1965. TRAC also recognizes the geographic changes of Louisiana in recent years, explaining to residents that the Gulf is much closer to them and their homes than it was in the past. The combination of these elements in its campaign drives home the message that many of the things that make Louisiana unique in a positive way also put it at increased risk.

In addition to TRAC's general public education campaign, TRAC developed tools and resources for primary school-aged children. Andy and Allie Alligator provide guidance for children through stories, an interactive Web site, a curriculum for teachers, and the song "Pack, Board Up, and Boogie." The same preparedness messages and information are transformed into a fun context so that kids can help their families remember everything that needs to be done in advance of a storm — including checking on the neighbors and "granny," and leaving well ahead of a storm's landfall.

TRAC also provides translations of most of its print and multimedia resources in French, Spanish, and Vietnamese as part of its efforts to ensure that it can reach all Louisianans. Part of TRAC's current efforts includes utilizing software that will automatically translate materials from English to the other three predominant languages in Louisiana. TRAC leaders are seeking resources to print hard copies of its materials in these additional languages through the local libraries and community organizations.

As TRAC has developed over the past 14 years, its leaders have learned that the messenger can be as important as the method of delivery. Peg Case, TRAC's Executive Director, learned that not all audiences will listen to her. However, a group of off-shore oil workers, for example, will listen to TRAC's message if their manager delivers it. As many studies have shown, people are more likely to listen to those they consider credible sources of authority.

Using FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grants and corporate donations, TRAC provides its Louisiana Storm Survival Guide through several outlets. TRAC realized early on that it could not rely on parish emergency management agencies alone to distribute its materials to residents. Over the years, TRAC has developed formal and informal distribution networks that include public libraries, Councils on Aging, home health networks, and direct response to anyone who calls the TRAC office. Web site visitors may chose to download the guide and other materials, or use the searchable online database to find the nearest library where they can pick one up. TRAC's efforts to broaden its distribution channels helped alleviate the potential "additional" work added onto emergency managers. Because of its distribution network, TRAC was able to distribute more than 260,000 copies of its guide in 2005.

The Louisiana Storm Survival Guide covers all stages of the storm cycle, from preparing homes prior to evacuation to providing New Orleans contraflow maps. It also provides information on tornadoes and thunderstorms — other common threats to Louisianans.

In addition to the Louisiana Storm Survival Guide, TRAC has published and produced the following as part of its Campaign for Storm Safe Louisiana:

- Vanishing Coast, Vanishing Safety... Surviving Louisiana Storms: A 30-minute preparedness program available on VHS and DVD. The video walks viewers through TRAC's 10-Step Hurricane Survival Plan.

- Teaching Disaster Readiness to Louisiana Kids: An instructor's guide for teaching children about storm preparedness.

- Andy and Allie Hurricane Series: A children's series developed to help prepare and cope with hurricane threats.

- Disaster Preparedness for the Elderly and Disabled: An instructor guide available for healthcare professionals with an elderly and/or disabled clientele.

- The Buddy Guide: Information for residents who want to learn how to help friends or neighbors who might need assistance in preparing for storms.

To help reach even more of Louisiana's residents, TRAC works with television stations and cable providers to broadcast PSAs. Currently, two announcements are available in four languages. These PSAs serve as a stark reminder to Louisianans that they are at risk.

A key component of everything that TRAC produces and prints is its toll-free number. TRAC's limited staff and volunteers make every effort to answer and/or return each call received. These personal points-of-contact provide the opportunity to talk with the inquirer about their specific situation and needs. The service also helps create a connection between the caller and preparedness because there is a real human on the other end — not just an answering machine. TRAC realizes that each caller has a story to share. Every inquiry is logged into a database for future reference and analysis.

After Hurricane Katrina

In the initial days after Hurricane Katrina, TRAC's employees found themselves in the unique position of having a working Web site and phone lines once they returned home. Many found TRAC on the Internet, and were looking for a way to help or get in contact with people in the area. TRAC responded by putting up an online database for volunteering and donations.

During the past few months, TRAC has focused on its other mission — mitigation. Since its founding in 1992, TRAC has worked to help individuals and groups rebuild or repair their homes to better survive the inevitable catastrophic storms and flooding. TRAC's success has resulted in a partnership with OxFAM to help expand this program and resources. One area under mitigation that TRAC's Executive Director Peg Case would like to provide more information on is the importance of having the right type of insurance. Without it, many will not be able to rebuild and move on.

In terms of its public education campaign, TRAC realizes that it needs to revise its videos and print materials to reflect the new realities and sensitivities. The organization is currently assessing the funding necessary to accomplish this goal. In the meantime, TRAC is still distributing the Louisiana Storm Survival Guide through local libraries and other partners. Although the landscape has changed, much of the information that residents need to know remains the same.

Additional Sources

The following documents and resources were used to research this practice:

- The TRAC Website. The site includes all resources listed in the practice.

- Peggy Case, TRAC Executive Director

- FEMA and the State of Louisiana. Promoting Mitigation in Louisiana Performance Analysis. March 5, 2002.

- Lewis, Joshua. "Louisiana Group Eyes Future Disasters." Disaster News Network. May 23, 2000.

- Dunn, Travis. "Interfaith Helps LA Survivors." Disaster News Network. March 11, 2003.

Alabama Successfully Implements Contraflow Plan, Then Reviews

With the annual threat of hurricanes and the need to prepare for other types of evacuation events, researchers and DOTs have been developing and refining contraflow plans for highway systems for many years. Contraflow plans, generally intended for large-scale events, enable transportation managers to increase capacity by reversing the traffic direction of one side of the highway.

The State of Alabama's Department of Transportation (ALDOT) developed its contraflow plan for Interstate 65 (I-65) several years ago, including a step-by-step checklist that ALDOT, the Alabama Department of Public Safety (ADPS), the Alabama Emergency Management Agency (AEMA), and other stakeholders utilize to implement the plan. Each year ALDOT, ADPS, and AEMA exercise the plan prior to hurricane season to test its systems, and serve as a refresher for those who have responsibilities if and when the plan is implemented. This year, the exercise will take place from May 17 to 18, 2006. The first day of the exercise involves the mobilization of personnel throughout the State and stepping up the alert system. The second day actually exercises the implementation of the contraflow plan, including manning all 30 traffic control points.

The Alabama Contraflow Plan includes the pre-positioning of dedicated equipment on trailers such as variable message signs in ALDOT's District Offices located close to the I-65 corridor. This plan addresses the need for additional resources throughout the State during an evacuation. While detailed, the plan is not rigid — to allow personnel in the field to make decisions on the ground.

The strength of the Alabama Contraflow Plan is partly due to the fact that ALDOT works with its partners to identify and apply lessons learned to the plan at the end of every hurricane season. This implementation has become more important during the past two years. While the contraflow plan existed for several years, it was not subject to a "real-life" test until Hurricane Ivan in September 2004. After their experience with Ivan, officials in Alabama recognized that:

- The real traffic conditions challenged the contraflow plan's gaps and assumptions identified during previous exercises

- Modifications to the northern terminus location, traffic, and traffic control in Montgomery needed to be made

- Although traffic volume was light, extrapolations to larger events meant that competing traffic movements needed to be reduced by splitting interchanges

- The intention to implement the plan on a response basis was false — the mere presence of ALDOT personnel contributed to the formation of queues, and to public outcry at the perceived failure of the contraflow plan

- Reversing traffic on the day of landfall put personnel and traffic control devices at risk once winds reached 35 miles per hour.

Alabama's experiences with contraflow during Hurricane Ivan resulted in an improved plan, and prepared the State for a successful evacuation in July 2005 before Hurricane Dennis struck. By this point, the contraflow plan had been switched to a schedule-based system. Governor Riley announced to the public that lane reversal would only be available 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on July 9. By scheduling the implementation of contraflow, personnel have time to get into position, clear the road, and stop lane reversal before nightfall. The limitation of contraflow to a day also helps with staffing issues as any extension would require identification and commitment of a complete second shift of personnel to contraflow, when they are needed elsewhere in the State.

Following Hurricane Dennis, ALDOT and its partners at AEMA and ADPS were ready to implement contraflow again for Hurricane Katrina before the storm turned towards Mississippi and Louisiana. Officials monitored the situation until they could make the decision not to implement a lane reversal.

As the State undergoes preparations for the 2006 hurricane season, it is also integrating additional changes to its contraflow plan. Officials are continuing to improve traffic patterns at the northern terminus. ALDOT and ADPS are collaborating to better define the roles and responsibilities of transportation personnel and state troopers acting in the field. One thing that Alabama officials have realized during the past two years is that the vehicles of state troopers are better suited to clear traffic — the public recognizes their vehicles and lights, and troopers have arrest authority that ALDOT personnel do not.

In addition to using the real-life experiences of Hurricanes Ivan and Dennis, ALDOT has refined the way it collects feedback following its annual exercise. Due to the length of the exercise and the requirement for many to travel overnight, ALDOT dismisses its participants immediately following the exercise. Officials realized that after two days, many people could not effectively contribute to a lengthy post-exercise briefing. ALDOT now asks participants for their comments via email, which not only has increased the response rate, but also has improved the completeness and relevancy of the comments. Because the quality of the feedback has been improved, it is easier to integrate the lessons learned and address identified gaps in the contraflow plan.

Other areas that Alabama recognizes as challenges to its contraflow plan include public perception of how fast traffic should move and the geography of its highway system. Media reports from the ground may find drivers who think that it will take between two and three hours to travel from the coast to Birmingham, a distance of approximately 250 miles. More realistic estimates would be a travel time of four hours during normal traffic, and seven to eight hours during periods of heavy traffic, including contraflow. Recognizing this problem, officials are looking at ways to improve media relations, and creating a brochure similar to Mississippi's.

The problem of Alabama's highway geography is more difficult to address. U.S. Route 31, the designated southbound route for responders and transportation personnel during contraflow, basically runs parallel to I-65. While there are many places where east-west connections between U.S. 31 and I-65 are relatively close, there are times that the distance between the two highways is more than 20 miles. Furthermore, U.S. 31 and other secondary roads serve as access to evacuation routes from the Alabama coast and Florida Panhandle. Traffic jams have developed in small towns and at intersections, affecting the entire highway system. Stretches of I-65's shoulder lanes could be dedicated to emergency vehicles. However, several bridges only have two-foot-wide shoulders, making it dangerous, if not impossible, for responders to travel against the contraflow traffic consistently. This is one reason why contraflow plans are meant to be implemented only in extreme situations.

ALDOT recognizes that their neighboring States' contraflow plans must account for a larger evacuating population as well as an increased number of people who do not own their own vehicles. Alabama experiences relatively less traffic from the coast, a significant portion of which is driven by tourists who have their own vehicles. Similar to comprehensive emergency management plans, contraflow plans must take into account the demographic and geographic features of the jurisdictions they serve.

Additional Sources

The following documents and resources were used to research this practice:

- George Connor, Alabama Department of Transportation

- Major Patrick Manning, Alabama Department of Public Safety

- FEMA National Situation Update: Sunday, July 10, 2005.

- Ball, Jeffrey, Ann Zimmerman, and Gary McWilliams. "Rita's Wrenching Exodus." The Wall Street Journal Online. September 23, 2005.

- Kaczor, Bill. "Hurricane Dennis roars toward the Gulf Coast after brushing past Florida Keys." The Canadian Press. 2005.

- Alabama Governor's Press Office. "Governor Riley Orders I-65 Lane Reversal on Saturday." July 9, 2005.

- Alabama Department of Transportation. "Plan for Reverse-Laning Interstate I-65 In Alabama."

- Wolshon, Brian, Elba Urbina, and Marc Levitan. "National Review of Hurricane Evacuation Plans and Policies." LSU Hurricane Center. 2001.

- Manning, Patrick. "Hurricane Evacuation Plan." Presentation at the February 14-15, 2006 Contraflow Workshop. Orlando, FL.

- The White House. "The Federal Response to Hurricane Katrina — Lessons Learned." February 2006.

Florida Uses GIS Technology to Aid in Collecting and Sharing Sheltering Information

A key component of Florida's State Emergency Response Team (SERT) is its use of GIS technology. One way that SERT uses GIS is to collect and provide information about open and closed shelters throughout the State to responders, government officials, and the public.

At the present time, one can access the State Emergency Operations Center (SEOC) Mapper database via http://www.eoconline.org/EM_Live/shelter.nsf to view a list of open and closed shelters, the availability of space at special needs shelters, and other relevant details. The longitude and latitude coordinates of shelters are pre-populated to allow for quicker updating. County officials may choose to input updated data about shelter availability via the Web or by calling the SEOC where the GIS team can enter information directly into the database. This information is updated frequently during a disaster, assisting emergency managers, first responders, and the public to receive the important information they need about the availability of shelters. Information from the Mapper program may be used by local officials to update the media about shelter availability, and help them decide where to place variable message signs (VMS) along major evacuation routes to direct people to shelters.

In addition to knowing where shelters are opened or closed, shelter operators rely on the outputs of models such as HURRicane EVACuation (HURREVAC), Consequence Assessment Tool Set (CATS), and Hazards US Multi-Hazards (HAZUS MH) to decide on the anticipated need for shelters inside and outside the zone of the storm's impact. Each model provides an information layer that can be processed and posted to the SEOC secure site accessible by all county officials in Florida. Model results from CATS include population impacts as well as damage to 27 different types of infrastructure, while HAZUS MH data includes damage cost estimates, debris amounts, and an estimate of the number needing shelter. The information on the secure site also contains information on evacuation routes and critical infrastructure that may be of importance when conducting a non-storm-related evacuation. Because SEOC Mapper is Web accessible, it is available anywhere where a connection can be established. For instance, some of the team that Florida sent to Mississippi in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina worked with the GIS team to obtain information using satellite phones to establish Internet connections.

Since the 2004 hurricane season, the SERT GIS team has begun developing the next iterations of the SEOC Mapper database, the first of which is targeted to be released around the beginning of June 2006. One of the GIS team's goals is to produce and provide real-time data. As the GIS team worked to improve back-end processes and redundancies, including moving to a multiple server system, it took into the account input from after-action reports and county emergency managers. One of the short-term improvements is to develop a more user-friendly system that will encourage more county officials to input shelter information directly into the system. The GIS team also hopes to provide a publicly available dynamic mapping system that will show only shelters that are open. Upon the release of the next version of the SEOC Mapper, the GIS team will provide training for system users.

In addition to these improvements, the GIS team hopes to provide the public with additional features, including a search by address function as found on popular Internet search engines, surge zones, shelters, and the real-time overlay of watch and warning zones. This will provide the public with the opportunity to learn the risks to their homes during a hurricane or tropical storm. GIS staff have also recently sought training on how to broaden its use of the HAZUS model to include flood situations and other disasters — all of which may require shelters to be opened in safe locations for evacuees.

Contacts

The following individuals provided information that contributed to the development of this practice:

- Patrick Odom, Florida Division of Emergency Management

- Arvil White, Florida Division of Emergency Management.

Orange County, Florida Support Emergency Management Plan with Training and Exercises

Orange County, Florida, has established an annual exercise program to determine the ability of local governments to respond to emergencies. This training and exercise program is coordinated by the Orange County Office of Emergency Management (OEM). County departments and authorities, municipalities, and all other public and private emergency response agencies also bear the responsibility of ensuring that personnel with emergency responsibilities are sufficiently trained. The Orange County CEMP also requires that all agencies take necessary steps to ensure appropriate records are kept reflecting the emergency training received by their personnel. This program consists of four parts:

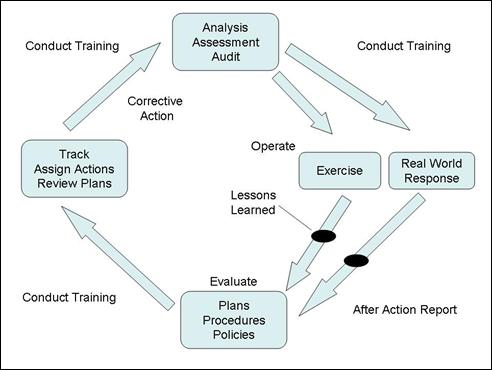

- Training Program — Under this program, OEM will coordinate all disaster preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation training provided to county personnel by the Florida Division of Emergency Management (FDEM) and FEMA. OEM will also provide schedules of the State emergency management training courses to appropriate county agencies. Applications for State and FEMA training courses will be submitted to the Executive Director of Emergency Management for approval and submission to FDEM. This includes training for local emergency response personnel. As part of the training program, the county has an Emergency Management Program Specialist (Education and Training) who is the point of contact for providing and coordinating the training and exercise cycle depicted in Figure H-1.

Figure H-1. Orange County Florida, Exercise and Training Cycle

- Exercise Program — Under this program, OEM ensures county disaster plans and procedures are exercised and evaluated on a continuing basis. Exercise after-action reports are completed and provided to participating agencies to ensure corrective action is taken. Subsequent exercises ensure previous discrepancies are reevaluated. Orange County's exercise and training program tries to involve public and private agencies with emergency response functions. Emergency management officials of adjoining counties may be invited to participate or observe when appropriate. Representatives from county, municipalities, and State and Federal agencies in the local area, as well as non-governmental agencies (e.g., Red Cross, Salvation Army, United Way, etc.) participate and share information on respective roles and responsibilities during disasters.

- Exercise and Training Requirements — Annually, OEM conducts a large-scale mass casualty exercise including pre-exercise planning meetings and a post-exercise critique. This includes the conduct of an annual hurricane exercise, which may be held in conjunction with a State-sponsored hurricane exercise. Other exercises include one or more emergency responder exercises involving mass casualties under various scenarios (e.g., Hazmat, transportation accident, natural disaster, terrorist act, etc.). The exercises also include hurricane briefings; emergency management activities; and hurricane preparedness and training meetings with the County Administrator and staff, department heads, municipal officials, and all other governmental and private emergency response agencies. Hurricane and emergency management seminars are conducted as requested. In support of ongoing training, the OEM conducts disaster-planning meetings with hospitals, nursing homes and assisted living facilities, shelter agencies, emergency transportation representatives, and home health care agencies.

- Public Awareness and Education — In this aspect, county officials work to keep residents informed about disaster preparedness, emergency operations, and hazard mitigation. Public information in the disaster preparedness and emergency management area is divided into three phases — continuing education, pre-disaster preparation, and post-disaster recovery and mitigation.

Additional Sources

The following documents and resources were used to research this practice:

- Orange County (Florida) Fire Rescue Department Office of Emergency Management and Emergency Support Function Planning Group. Orange County Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan. Updated May 1, 2003.

- Orange County Government, Florida. Emergency Planning Website. 2006.