U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

FHWA Resource Center

Office of Innovation Implementation

Click here for the PDF Version of the Environmental Quarterly

To view PDF files, you need the Acrobat® Reader®

Volume 6, Issue 2

Spring 2010

INSIDE

• Answers to NEPA Quiz Questions (and NEW questions to answer)

• Best Practices in Addressing NPDES and Other Water Quality Issues

• Summit Focuses on Air Quality

• 40th Anniversary: NEPA Recollections

• 2010 US DOT Tribal Consultation Plan

• How Swiss Bikers Saved the Blues

• Environmental Calendar

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Environmental Colleague

Greetings readers and welcome to the spring edition of the Environmental Quarterly. I would like to take this space to recognize a couple of individuals and wish them well in their new adventures.

FHWA is losing two of its finest environmental folks. Carol Adkins (HQs) and Steve Thomas (Arizona Division) are saying so long to FHWA this year. In fact, by the time this is published I believe Carol will already be relaxing leisurely by the pool. Steve takes his leave in June and I’m sure has lots of interesting plans that don’t involve us. I imagine he is already letting his hair and beard grow in preparation for his new life. I have known and worked with Steve and Carol for many years and can tell you that both of them are dedicated professionals and fantastic people. For more than 30 years, Carol calmly and thoughtfully considered the best interests of the agency and the environment in everything she did. Steve and I spent many hours discussing how things would be better if they would just listen to us. We will miss you Steve and Carol but are happy for you. Good luck Carol. Good luck Steve. Keep in touch, please.

Sincerely, Lamar Smith

Environment Technical Service Team Manager & Editor–in-Chief

Phone: (720) 963-3210

E-mail: lamar.smith@dot.gov

[start of article 1]

Remembering Dickie Walters

Lamar Smith, Kevin Moody (FHWA Resource Center); Claiborne Barnwell, (MS DOT)

Photo of Dickie Walters.

We are extremely saddened to have to tell you about the untimely passing of Dickie Walters of the Mississippi Division Office, who passed away unexpectedly on March 22, 2010. He passed away while jogging, a sport he truly loved. Dickie was extremely well liked by everyone who knew him. Upon learning of Dickie’s death, Pam Stephenson, ADA in the DC Division, referred to him as a true southern gentleman. For those of us from the south, we know this to be a great honor. Dickie was known for the joy and fun he created wherever he went. Colleagues and friends will very much miss his remarkable personality. He loved to share the great things in life, his keen sense of humor, and his devotion to his wife Janie, an internationally known motivational speaker and author.

Dickie was a global traveler. He particularly enjoyed Colorado for skiing and Europe for the fine food and drink. He was well known for his discerning enjoyment of Italian greyhounds, fine food, and great cigars. Locally, he was known as an aficionado of the Dinner Bell diner in McComb, MS. The Dinner Bell is one of those places where 10 to 12 people, often strangers, gather around a large round lazy-Susan style table, and eat family style. He could not get enough of their fried catfish, fried green tomatoes, and other traditional southern dishes.

Dickie’s professional life was shaped around public involvement and doing right by the public. He believed very strongly that the public should be informed about, and engaged in public agency proposals and decisions. He was an aggressive proponent of public involvement in all projects. After working many years as a civilian environmental program staffer at Keesler Air Force base in Biloxi, MS, Dickie came to the FHWA. He worked with us for nearly 10 years as a valuable team member who demonstrated a great deal of commitment to the Agency and its mission. As an Environmental Protection Specialist in the Mississippi Division, he skillfully dealt with environmental issues and provided expertise in advancing environmental stewardship and streamlining project delivery. His guidance was instrumental in getting the concept of context sensitive solutions mainstreamed into the project development process. He was also adept at cultivating professional relationships with state and other Federal agencies involved in the environmental decision-making process. In particular, he developed a strong alliance with the American Indian Tribes.

Dickie was simply one of the best. His colleagues and counterparts knew that they could count on his expertise and selfless dedication. They thought of him not only as an expert in his field, but also as a friend. He will be sorely missed. On behalf of the Mississippi Division Office, the Resource Center Environment Technical Services Team, and the entire FHWA Environmental Discipline, we wish to express our deepest sympathy and best wishes to his family, friends, colleagues, and to the public who has lost a great ally.

[end of article 1]

[start of article 2]

Next NTAQS to Be Held This Summer in Cambridge, MA

The Northern Transportation Air Quality Summit 2010 (NTAQS 2010) will be held August 24-26 at the Cambridge Marriott in Cambridge Massachusetts. NTAQS, like the Southern Transportation Air Quality Summit (STAQS), is held every two years to discuss current and coming regulatory environment, technologies and current practices vital to the field of air quality and transportation. Topics such as conformity, the CMAQ Program, modeling and analysis associated with conformity and project analysis, revision of air quality standards, climate change, and other issues relating to air quality, the environment and planning are covered. NTAQS 2010 may also provide an opportunity for training, depending on the time available. For additional information, contact Kevin Black at 410-962-2177 or Kevin.Black@dot.gov.

[end of article 2]

[start of article 3]

Interested in receiving the Cultural Resources Bulletin, a publication of the Maryland DOT?

Contact Nichole E. Sorensen-Mutchie, M.S, RPA at 410-545-8793 or NSorensenMutchie@sha.state.md.us. The Winter 2010 edition is available now.

[end of article 3]

[start of article 4]

NEPA Quiz Answers

Lamar Smith, FHWA Resource Center

In the last issue of the EQ I proposed three trivia questions regarding the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. The questions were more fun than informative. Thanks to those that took the time not only to answer or guess at the questions but also to send your responses to me. I enjoyed reading and talking to some of you about them. I hope others at least considered the questions and did a little research. The history of NEPA and how it came to be is quite interesting and spans more than five decades.

As a reminder, the questions I posed were: 1) Why did President Richard Nixon sign the Act on January 1, 1970 instead of earlier as he had planned, and where did he sign it? 2) Who has been given the honor of the title, the "Father of NEPA"? 3) Who was appointed the first Chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality? As promised, the answers to the questions, at least according to me, follow.

It’s interesting how different individuals and organizations have recorded Nixon’s reaction to and support of the environmental movement and NEPA. Some sources report his endorsement as reluctant and political. Others suggest or claim that he had a sincere concern for the environment and celebrate his action as that of the "Environmental President." Regardless of what is written or what we individually believe, the fact remains that for what ever reason or motive, President Nixon signed NEPA into law on January 1, 1970 and launched the "environmental decade". As he remarked at the signing, "It is particularly fitting that my first official act in this new decade is to approve the National Environmental Policy Act". NEPA was the first law passed in 1970, signed at 10 am on New Years Day in his office at the Western White House in San Clemente, CA. It may well have been a carefully calculated political decision but as they say, the rest is history.

The birth of the environmental movement and the eventual passage of NEPA have been well documented. If you have read much of the history you will have noticed that several individuals emerge as hero, villain, politician, or combination of the three. A few of the more notable figures include Senator James Murray of Montana (in 1959 he introduced the Resources and Conservation Act, a predecessor of NEPA), Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin (principal founder of Earth Day), Senator Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson of Washington (perhaps the notable figure of all), Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine, and Congressman John Dingell of Michigan. As their association with environmental issues and NEPA varies, each deserves credit in some way with the establishment of our existing national environmental policy. The "Father of NEPA", however is generally considered to be Lynton Caldwell. In 1968 Mr. Caldwell as a consultant for Senator Jackson drafted a White Paper entitled, A National Policy on the Environment, which was the starting point of what would be discussed, debated, negotiated and eventually become the National Environmental Policy Act. Lynton Caldwell believed that more was needed than a mere policy statement and that an "action-forcing mechanism" would help secure Federal agency compliance with the NEPA Section 101 goals. The action forcing mechanism would become the detailed statement that eventually became the environmental impact statement that we are all so familiar with. So, while often thought of as the Father of NEPA, others have honored him as the "architect of the environmental impact statement." Not that it really matters but there is evidence that his idea was never realized.

The last question was the easiest of the three. The first Chair of the Council on Environmental Quality was Russell Train. I did not have the pleasure of meeting him personally, but Fred Skaer (a mentor of mine, among other things) did at a function several years ago and acquired for me an autographed copy of his book, Politics, Pollution, and Pandas: An Environmental Memoir. The inscription reads, "For Lamar, Best wishes to a NEPA careerist!" It is a prized possession.

Much history has been written on NEPA and the events surrounding its creation. If you are interested, all you have to do is visit the World Wide Web and with a few artful strokes of the keyboard, you too can be a NEPA scholar. I would like to point out one article in particular on the history of NEPA written by the Federal Highway Administration’s own Richard Weingroff. The Article, Addressing the Quiet Crisis: Origins of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, provides a look at NEPA and includes an Agency perspective on NEPA implementation in the early days.

At this time it is only fitting that I offer my personal thanks to President Nixon, Senator Jackson, Lynton Caldwell, and all those involved in establishing the National Environmental Policy Act and providing me with a very rewarding career.

Before I sign off, I thought I would give you some additional trivia questions to ponder? 1) What other U. S. President deserves at least an honorable mention in the evolution of the NEPA process and why? 2) With all the men involved and recognized, was there any women given credit for NEPA in any way? 3) What Federal agency has considerably more NEPA responsibility than any other? And a Bonus question: In what way do you think NEPA has evolved (and is evolving) beyond the original intent?

I have become…convinced that the 1970’s absolutely must be the years when America pays its debt to the past by reclaiming the purity of its air, its waters, and our living environment. It is literally now or never.

--President Nixon’s Signing Statement for the National Environmental Policy Act,

1 January 1970

For more history and information regarding the evaluation of the environmental movement in general and the National Environmental Policy Act as it relates to the Federal Aid Highway program, consider reading "Addressing the Quiet Crisis: Origins of NEPA".

[end of article 4]

[start of article 5]

Best Practices in Addressing NPDES and Other Water Quality Issues in Highway System Management

Brian Smith, FHWA Resource Center

Caption: A photo of the brochure Best Practices in Addressing NPDES and other Water Quality Issues in Highway System Management

An NCHRP Domestic Scan was completed in the summer of 2009. The Domestic Scan program is conducted cooperatively between FHWA, AASHTO to facilitate the transfer of technology between State DOTs. The scan completed in June 2009 investigated issues surrounding implementation DOT stormwater programs and covered four topic areas of special interest. The four topic areas were TMDLs, BMPs, DOT Practices/Procedures and working relationships with regulatory agencies. The final report for this scan effort, Domestic Scan 08-03 Best Practices in Addressing NPDES and Other Water Quality Issues in Highway System Management, is being published on the TRB project web page:

This report discusses a wide array of innovative practices, and formulates improvement strategies for DOT stormwater programs and future stormwater quality research. Recently, the scan findings were featured at the National DOT Stormwater Practitioner’s Conference in April 2010, in a March 2010 CTE webcast, and the January 2010 TRB Conference.

[end of article 5]

[start of article 6]

Spring is in the Air: Summit Focuses on Air Quality

Leslie Sweet Myrick, Illinois Center for Transportation (ICT)

As spring creeps into the air, states including Illinois, have new information, tools, and support from Federal, state and local air quality officials as they work together to comply with Federal air quality standards, reduce the impacts of hazardous air pollutants, and address climate change.

The recently published proceedings from the Midwest Transportation Air Quality Summit include discussions from 64 representatives of Federal, state, regional, and local transportation or air agencies in the Midwest about the current and upcoming challenges affecting both transportation and air quality planning in the Midwest. The states represented at the summit included Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

The information shared and documented at the summit will have positive implications for air quality in the Midwest as the officials charged with implementing and enforcing the standards shared best practices and experiences. Because many air quality issues are affected by the transportation sector, it is important for air and transportation officials to work together cooperatively.

Michael Koerber of the Lake Michigan Air Directors Consortium, in conjunction with the Illinois Department of Transportation, organized the summit which included a total of 42 presentations made by 32 speakers. The format allowed for audience participation with question-and-answer periods in each session and two short open round-table discussions. Koerber explains, "Our hope was to provide a foundation for Midwest air and transportation agencies to begin to develop appropriate and effective approaches for achieving cleaner air in the region."

The Conference sessions included state implementation planning activities for new air quality standards, mobile source emission inventories (and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s new MOVES emissions model), highway project-level analyses, current diesel engine programs, climate change, mobile source air toxics, and on-going mobile source-related research studies.

According to Walt Zyznieuski, Air Quality Specialist for the Illinois Department of Transportation, "The Midwest Transportation Air Quality Summit was very successful in that it brought together Federal, state, and metropolitan planning organizations to discuss various air quality issues and emerging topics. In addition, round-table discussions were useful in identifying and laying out solutions for participants."

The summit convened at Pere Marquette State Park in Grafton, Illinois, in fall 2009, and the proceedings were recently published. The Summit was sponsored by the Illinois Center for Transportation (ICT), a innovative research partnership between the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) and the University of Illinois. For more information about the ICT and to view the conference proceedings, which are included on the ICT Publications Page, visit http:ict.illinois.edu.

For more information on the conference, visit the LADCO website. Contacts: Principal Investigator Michael Koerber (LADCO) Koerber@ladco.org or Leslie Myrick (ICT), lsweet@illinois.edu or 217-893-0705 x225.

[end of article 6]

[start of article 7]

NEPA’s 40th Anniversary

NEPA Recollections: The Passage, Implementation and Meaning of NEPA

Editor’s note: A questionnaire was sent to a variety of FHWA and DOT leaders, current and former, who had experience with NEPA. The questionnaire asked a variety of questions about their experiences and impressions of NEPA. This is the first in a series of articles in which we share their answers to some of these questions.

What do you remember about the events or circumstances leading to the passage of NEPA?

"I started my career with FHWA (then called the Bureau of Public Roads) several years before NEPA was enacted. At the time construction of the Interstate System was well underway and engineering factors, costs, and safety were the primary considerations. In the interest of reducing costs the Interstate System was often located in areas, which by today’s standards would be considered sensitive areas, such as in swamps (now referred to as wetlands), in low income neighborhoods, etc.. While the Interstate System, and other highway and transportation projects, provide huge benefits to the American public in terms of mobility, safety, and the economy, they also had unintended environmental and social impacts. This, together with impacts from other Federal programs, led to considerable concern and pressure by elected officials; some Federal, State, and local agencies; special interest groups; and the general public for greater consideration of social, economic, and environmental issues during the development of Federal programs and projects. This culminated in passage of the National Environmental Policy Act which requires, among other things, that major Federal actions which significantly affect the quality of the human environment consider the environmental affects of their actions."

- James M. Shrouds has 35 years of involvement with NEPA. He is an independent consultant working on transportation and environmental issues. At the time of his retirement from FHWA, he was the Director of the Office of Natural and Human Environment.)

"My first day with FHWA was 7/01/69. I was in my first Federal-aid assignment in Delaware Division when NEPA became law (Jay Miller, Division Administrator). No memories about the Congressional deliberations, but considered the Nixon signing oxymoronic (Environmentalist President?)."

- Jim. St. John has 37 years of involvement with NEPA. He is a part-time advisor for HNTB. He is retired from FHWA.

"Not much, I was in high school."

- Fred Skaer, Director of the Office of Project Development and Environmental Review, has been involved with NEPA for over 30 years.

What do you remember about the early implementation of NEPA (including events such as the first Earth Day)?

"The early implementation of NEPA was very challenging because of the lack of experience in developing environmental documents and a lack of expertise in many of the environmental areas. Compared to today’s sophisticated modeling and analyses techniques, advances in mitigation strategies, and comprehensive environmental documents, the documents in the early 1970s were often brief, rudimentary, and subject to may lawsuits. However, considerable progress was made by FHWA and the State DOTs in the 1970s as a result of CEQ guidelines in 1971 which assisted agencies in the development of their own procedures, CEQ regulations in 1978, agency regulations, etc. All of these regulations and guidelines, as well as on-the-job experience gained in coordinating with resource agencies and preparing environmental documents, helped to rapidly advance the state-of-the-practice in dealing with NEPA and other environmental requirements. Early lawsuits and court decisions also helped clarify certain provisions and requirements and many of them were incorporated into agency guidelines and regulations."

- James Shrouds

"On the first Earth Day, I was a forestry student at the McKeesport Campus of Penn State and was inspired to switch to a new major at Penn State--Environmental Resource Management (ERM). The major was structured around the interdisciplinary concept. As an ERM student, I founded the Organization of the Ecologically Concerned which became the ERM Club. Also, I took course in Environmental Law which covered NEPA and the other landmark Federal environmental legislation. I was in the first graduating class of ERM with 10 other students in 1973.

"The early implementation of NEPA focused on fulfilling the documentation requirements more than making good decisions. In many cases, NEPA implementation meant justifying project development decisions that were already made. Transportations had an extensive backlog of projects on the shelf where the location and design were determined prior to or in the absence of NEPA studies and public involvement. This meant that there were superficial alternative analyses performed which were biased toward a predetermined alternative. There was extensive use of university professors as consultants used to fulfill the interdisciplinary requirements of NEPA. Many early DOT environmental managers were engineers and biologists, rather than environmental resource managers. Federal and state regulatory and resource agency staff were engaged late in the NEPA process, usually at the DEIS circulation stage. In many cases, the regulatory agency staff did not get engaged until a permit application was filed. NEPA was not used as an umbrella to satisfy all of the environmental requirements. The environmental requirements were satisfied sequentially and unilaterally. EIS’s read like encyclopedias rather than stories of the decision process."

- Wayne W. Kober has 36 years of involvement with NEPA. He is the President of Wayne W. Kober, Transportation and Environmental Management Consulting and a former Director of the PENNDOT Bureau of Environmental Quality.

"While a trainee in New York Division, I was involved with a triage exercise to decide which projects required NEPA work, and which were "grandfathered" forward (business as usual). I think having project design approval, but not final plan approval, triggered more work to be done. A series of PPM’s and other directives flowed to the field offices in rapid succession. In hind sight, FHWA response to these early guidance/requirements launched us on an escalating bureaucratic and legal spiral costing time and money from which we have never recovered. More rhetoric required here to explain, but the essence is FHWA used the project detail on hand to define and address very detailed and specific impacts. We taught the environmental agencies, watch-dogs and the courts that FHWA could supply finite details to address NEPA and companion laws, regulations and policies. Setting the bar with minutia we had available on these "almost ready to build" projects set expectations for future "start from scratch" projects way too high, and insured huge time and money efforts leading to huge documents (aka, administrative records). Certainly our colleague Ed Kussy needs to input here! By 1975 FHWA was fully engaged building its agency NEPA response capabilities, and while I was an Area Engineer in New Jersey, I chose the NEPA specialty to be the keystone for my career. Through this time, I considered each Earth Day itself to be a politically required waste of time for FHWA employees. Let me tell you about "The Retreads" – Shrouds, Berube, Smith, Walls, and St. John (there was one other I am not recalling). Imagine – take FHWA civil engineers and add an environmental conscience center in their brains! This led to my Masters Degree in Interdisciplinarity."

- Jim St. John

"I remember FHWA working with the States to institutionalize NEPA through the development of Action Plans. This took several years to do, but seemed to be a reasonable approach for integrating the new concepts into what was essentially a civil engineering work flow."

- Fred Skaer

What does NEPA mean to you?

"NEPA means that the Federal decision making process is transparent and offers the opportunity for agencies, organizations, and the public to review and comment on purpose and need, alternatives, impacts, and mitigation associated with Federal actions. NEPA means that citizens can legally challenge Federal decisions before implementation of regulations, programs, management actions, and projects. NEPA means that environmental documents must be understandable to laymen. NEPA means that it may be appropriate to choose the do nothing alternative."

- Wayne Kober

"The "Policy", is a beautifully articulated vision for the Nation, and an inspiration on its own merit…Forty years forward brought us Environmental Enhancement, Context Sensitivity, Environmental Stewardship, Eco-Logical, Green Infrastructure, Sustainability and Livability. Each initiative, a step towards ‘…enjoyable harmony between man and his environment…’, the vision embodied in NEPA. On a world scale, NEPA has been a powerful influence and a model for other countries to build on. As a former US representative on the Environmental Committee of the World Road Association (PIARC), I saw firsthand how the vision of NEPA has been adapted to other nation’s policies and project development practices. The shared interest among international colleagues in seeking ways to pursue the NEPA vision in transportation programs was exhilarating and an honor to a part of. Perhaps the World Road Association can be invited to share in the 50th Anniversary celebration of NEPA."

- Andras Fekete has 38 years of NEPA experience and currently works with The RBA Group.

"It is the right way to do government business. Now, if we could only do it right."

- Jim St. John

"To me, NEPA is a primarily national commitment. The commitment is to think broadly and prudently before moving ahead with actions that may have serious unintended consequences."

- Fred Skaer

[end of article 7]

[start of article 8]

2010 USDOT Tribal Consultation Plan

On November 5, 2009, President Obama signed a Presidential Memorandum on Tribal Consultation. This Memorandum affirms the Administrations commitment to regular and meaningful consultation and directs each agency to prepare a plan to implement Executive Order 13175 and prepare interim and annual progress reports. On Tuesday, March 2, Secretary LaHood announced the finalization of the USDOT Tribal Consultation Action Plan at the National Congress of American Indians mid-year conference in Washington, DC. The USDOT plan is posted on the FHWA Tribal website.

The Plan incorporates comments received from Indian tribal governments and was developed by a team made up of representatives of each DOT mode.

Activities that the FHWA has been involved in for several years are reflected in the Plan. It is an extension of many of the efforts FHWA has made over the years in consulting with tribal governments and developing government-to-government relationships. The FHWA will continue with the consultation efforts that have been part of our efforts for the past decade.

USDOT is required to submit a progress report and annual updates on the Plan. In December 2009 the FHWA Division offices provided information and updates on consultation efforts with Indian tribal governments. This provided an excellent base of information on the current state of FHWA/State/tribal consultation and will assist the Secretary’s office in required progress reports.

[end of article 8]

[start of article 9]

How Swiss Bikers Saved the Blues

Cecil Vick

Cecil Vick is a native Mississippian and was a Right of Way and Environmental Specialist for the Mississippi Division Office of FHWA. He retired in 2009 and now manages environmental and planning activities for the Jackson, Mississippi, Office of ABMB Engineers, Inc., a multi-state engineering consulting firm.

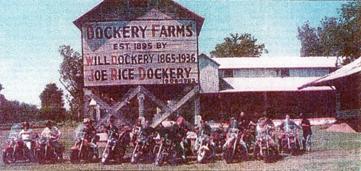

Caption: Photo of Dockery Farms building with people on motorcycles in front.

Today, one of the important growth industries in Mississippi is blues tourism. When this story took place, the state tourism industry was just beginning to realize how important the Delta Blues is to Mississippi’s history and to the evolution of modern music.

As the Environmental Manager for FHWA’s Mississippi Division Office, I spent thirty years in the development of transportation projects, many in the Delta.

The Mississippi Delta is about fifty miles wide. Tennessee Williams said it begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and stretches southward some two hundred miles to Catfish Row in Vicksburg. It is a land of extreme poverty contrasted with small pockets of intense wealth. It is known mostly for cotton, catfish, and the Delta Blues. The economic, cultural, and physical hardships of the Delta gave the blues its soul. Blues music has contributed significantly to modern rock and roll, progressive country, jazz, hip-hop, and more.

I became personally involved with blues history when the Mississippi Department of Transportation (MDOT) scheduled a public meeting for a project to four-lane 13 miles of Highway 8 through the Delta from Cleveland to Ruleville. It looked like a simple widening project. MDOT was proposing to add two lanes and a median adjacent to the existing two lanes. This part of the Delta is primarily agricultural and suited for cotton, soybeans, and catfish farming. There were no real major environmental issues; and, based on an archeological study, the State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO) had agreed with the DOT that no historic sites would be affected. The preferred alternative would take an abandoned store and perhaps a church. I had not looked at the project on the ground.

While attending Context Sensitive Solutions training near Memphis, it occurred to me that if this project was going to take a church I needed see it. On the way home I drove through the project area looking for the church, and found the headquarters of an old cotton plantation. I recognized that the church and store had been part of the plantation headquarters. The barns and storage buildings, an old cotton gin, the church, and the plantation’s commissary or "company store" were still there. There were many similar plantation headquarters around when I was a child, but they are rare today. On one of the barns was painted, "DOCKERY FARMS est. 1895." The church was original, but it was old. The company store looked like it replaced the original one in the early twentieth century. I began to suspect that this might be a National Register eligible historic site or district that the surveys had overlooked.

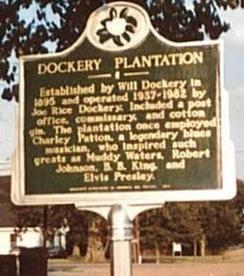

A closer look at the commissary revealed it to be covered with graffiti of the names of rock and roll bands like ZZ Top, Stevie Ray Vaughn, and Aerosmith. Quite a few people had signed their names and where they were from. They were from places like London, France, Sweden, and Japan. There was a state historic marker that read, "The plantation once employed Charlie Patton, a legendary blues musician, who inspired such greats as Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson, B.B. King, and Elvis Presley." I knew if Elvis was involved, this had to be important.

Back at the office, I started researching Dockery Plantation on the Internet. The first site I found was in France, and it described Dockery Farms as the most important blues site in America and probably in the world. I found references to Dockery everywhere I looked. In the 1920's, Dockery Plantation was home to several hundred workers. Among them, in addition to Charley Patton, were legendary bluesmen Willie Brown, Henry Sloan, Tommy Johnson, and Roebuck "Pop" Staples. They knew each other and worked together to develop the Delta Blues. They played at Dockery and travelled on the Pea Vine Railroad, which bisected the plantation, to places like Rosedale, Clarksdale, Cleveland, Memphis, and juke joints all over the Delta. These bluesmen were contemporaries of Robert Johnson, Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson, and Howlin' Wolf. Their songs influenced the development of American popular music which spread all over the world.

With only a few days before the public meeting and with a preferred alternative proposed through the site where B. B. King has been quoted as saying, "This is where it all began," I met with MDOT’s Environmental Director and the Division Administrator and expressed my concern for the possible oversight of this important historic site. The DOT Environmental Director was resolute in his support of the preferred alternative because it was cheaper, and had been "cleared" by the SHPO. I’m not sure he had much appreciation for the blues either. The Division Administrator supported my position, but agreed to allow the presentation of the preferred alternative at the meeting He made it clear that there is a difference between a preferred alternative and a selected one and that the decision had not yet been made.

I believed him, but was nervous. I was lying awake at night thinking about the guilt I would feel if I let anything happen to the birthplace of the blues. What if the Division Administrator and I were hit by a bus? As luck would have it, the editor of a magazine about Delta culture became aware of the public meeting through an anonymous email that said, "Tomorrow evening there will be a public meeting at Dockery Farms about four-laning Highway 8. The plantation buildings could be affected. You might want to attend."

Shortly thereafter, a group of 30 bikers from Switzerland arrived at Dockery Farms on Harley-Davidson motorcycles to stage a blues sing-in and to support the preservation of the Dockery site and buildings. Apparently, that anonymous email had travelled pretty far in a short amount of time. The Swiss bikers had traveled to America, rented bikes in New Orleans, and were touring Delta Blues sites. They spent the entire morning protesting and singing the blues--often in German. Biker Phillip Franchiser told the Bolivar Commercial that Dockery is a very important and well known blues site to European blues fans: "Dockery Farms is very prestigious in Switzerland. It’s a big mysterious legendary place. Anyone who knows anything about the blues knows about people like Charlie Patton and Will Dockery. I’m really glad to be here."

Caption: Photo of sign about Dockery Plantation.

After a day of protest, the 30 Swiss bikers put on their helmets, fired up their hogs, and headed off in the direction of Chicago. Their visit helped to end any discussion of taking land from Dockery Farms. Later, Dockery Farms became the first of many sites showcased on the Mississippi Blues Trail. Today Mississippi blues tourism is big business, and Dockery is included on every commercial blues tour.

There was really no need for me to send that email about the public meeting, but I am proud that I did. I was careful not to tell anyone that I had sent it, so I was surprised when the Division Administrator brought me a letter from the Director of the Mississippi Department Archives and History thanking me for my intervention. It said, "Dockery Plantation is one of the most significant blues heritage sites in the state. It would have been a tragedy to lose this cultural landmark. . ." I have never verified this, but I am told there is a copy of that letter in the archives of the Dockery Farms collection in the Mississippi Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale.

Biker photograph and biker quotes with permission of "The Bolivar Commercial," Cleveland, MS.

Caption: Stylized photo of Dockery Farms.

CONTACT INFORMATION:

Federal Highway Administration

Resource Center

Editor-in-Chief

Lamar Smith, Environment Technical Service Manager

Phone: (720) 963-3210/Fax: (720) 963-3232

E-mail: lamar.smith@dot.gov

Editorial Board Members:

Bethaney Bacher-Gresock, Environmental Protection Specialist

Phone: (202) 366-4196/ Fax: (202) 366-7660

E-mail: bethaney.bacher-gresock@dot.gov

Brian Smith, Biology/Water Quality Specialist

Phone: (708) 283-3553/Fax: (708) 283-3501

E-mail: brian.smith@dot.gov

Stephanie Stoermer, Environmental Program Specialist/Archeologist

Phone: (720) 963-3218/Fax: (720) 963-3232 E-mail: stephanie.stoermer@dot.gov

Deborah Suciu-Smith, Environmental Program Specialist

Phone: (717) 221-3785/Fax: (717) 221-3494 E-mail: deborah.suciu.smith@dot.gov

Managing Editor

Marie Roybal, Marketing Specialist

Phone: (720) 963-3241/Fax: (720) 963-3232

E-mail: marie.roybal@dot.gov

Production Schedule:

Due to our Quarterly publication schedule, all article submissions for future issues are due to the Editor-In-Chief by the 10th of March, June, September, and/or December

Getting the news:

*If you would like to receive this newsletter electronically, please send your email address to: bob.carl@dot.gov