CONTENTS

FIGURES

TABLE

This chapter identifies the local governments with taxing authority that can use TRZs to fund transportation projects. It also describes the types of projects that could be partially or completely funded with TRZ revenues. Finally, this chapter discusses the most common TRZ financing mechanisms.

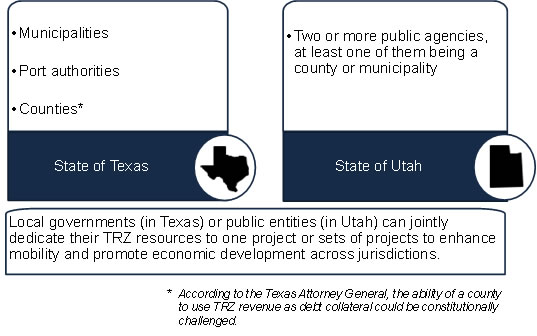

Texas law allows municipalities, counties, and port authorities to establish TRZs within their taxing jurisdiction.5 However, in practice, counties have faced legal issues when trying to establish a TRZ. In this regard, the Texas Attorney General has indicated that Texas counties are constitutionally prevented from using tax increment financing (TIF) revenue to repay debt incurred for a project (including a transportation project) aimed at developing or redeveloping an area within the county. More specifically, the Texas Attorney General has made it clear that using county TRZ revenue to secure debt could be constitutionally challenged, and that even collecting and using county TRZ funds on a pay-as-you-go basis may also be subject to constitutional challenge.x

Figure 4. Local jurisdictions that can use TRZs. (Source: Texas A&M Transportation Institute)

On the other hand, Utah law indicates that a TRZ can be created by two or more public agencies, provided that at least one agency has land use authority over the area where the TRZ will be created.xxxi According to Utah Code, public entities with land use authority include municipalities and counties.xxxi, xxxii Moreover, the Utah Code also states that municipalities and counties are the public entities that have the taxing authority (i.e., sales and use tax and property tax) required to create a TRZ. xxxiii, xxxiv

In cases where there is a common interest and it is politically and economically appropriate, local governments (in Texas) or public entities (in Utah) can jointly dedicate their TRZ resources to one project or sets of projects to enhance mobility and promote economic development across jurisdictions. For example, Texas law allows for joint administration of TRZs created by adjoining municipalities in order to facilitate funding projects that have a common interest across two or more municipal jurisdictions. Additionally, there are cases where two or more local government taxing jurisdictions overlap geographically. For example, under the Texas legal framework for TRZs, a port authority and one or more municipalities within the port authority boundaries could set up separate TRZs and jointly fund a project of common interest.

As noted in Section 2.3.1, Texas law allows for the creation of a TRZ for a variety of transportation projects, including, among other examples, tolled and non-tolled roads, passenger or freight rail facilities, certain airports, pedestrian or bicycle facilities, intermodal hubs, parking garages, transit systems, bridges, certain border-crossing inspection facilities, and ferries. Moreover, Texas law does not limit the use of TRZ funds to State or Federal transportation projects.iv In practice, this means that TRZ funds can be used on local transportation projects not linked to a State facility as long as the local government is not planning to seek State infrastructure bank (SIB) loan financing and is instead planning to use the pay-as-you-go or municipal bond financing options. The restriction to projects linked to a State facility is not connected to the use of TRZ funds or to the TRZ statute, but rather to the choice of SIB financing (see Section 4.3.3 for more details).

In Texas, TRZs have been used to fund projects in a variety of settings. There are examples of projects in large urban areas, such as El Paso, and in suburban communities, such as the Town of Horizon City. Rural communities, such as El Campo, have also successfully used TRZs to fund transportation improvements(3). As a result, the scale of improvements where TRZs have been applied ranges from direct connect links at large interchanges on the interstate system to smaller capacity additions on the State highway system.

On the other hand, Utah law does not define the specific transportation projects that can be funded using TRZ revenues. Instead, it allows the local governments to define the transportation need and proposed improvement within the zone. Moreover, Utah law does not explicitly require a finding of underdevelopment or blight as a precondition for establishing the zone. xxx This translates into more flexibility for local governments when selecting a transportation project to fund. Finally, Utah law does not limit the use of TRZ funds to local, State, or Federal transportation projects.

TRZs are generally not intended to serve as the sole funding mechanism to deliver a transportation improvement(2). Rather, TRZ revenues are often used as a complementary funding source to help local governments meet the local match when required to access certain traditional State and Federal funds or to pay for project development costs. There is no legal requirement or limit on the portion of a project’s cost that can be funded using TRZ revenue. However, in practice, TRZ experience to date indicates that TRZ funding is primarily used as a gap financing tool to pay only for a portion of the project cost. In these cases, paying for 100 percent of the project cost could put an undue burden on local government funding and financing.(7)

Experience in Texas has shown that there are three main financing options available for TRZ revenue funds, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. These are: (1) pay-as-you-go, (2) municipal bond financing, and (3) SIB loans.xxxv TRZs generate revenue in annual increments, commencing in the base year (the year in which the TRZ is created), as illustrated in Figure 1. Since annual revenues are driven by growth in the tax base within the zone relative to the base year, the initial years normally provide relatively small increments in revenue growth. Small annual increments in the early years of the TRZ means limited flexibility in using the funds on a pay-as-you-go basis. As a result, TRZs are most effective when future TRZ revenues are pledged to secure capital needed to implement the project through debt (e.g., municipal bond financing or a loan).xxxvi

Pay-as-you-go refers to the financing of improvements using current revenues, such as general taxation, fees, and service charges(8). Under this option, the local government has to maintain annual project expenditures within the budget constraints set by actual annual TRZ revenue. This strategy has the advantage of not entailing a financial (interest) cost, but also has the significant disadvantage of a slow project delivery because of capital constraints.

Municipal bonds are debt securities issued by States and local governments (e.g., municipalities and counties) to fund day-to-day obligations or capital expenses, such as transportation projects (9). In this option, the local government may seek financing from the capital markets, pledging future TRZ revenue as a collateral. This option has the advantage of providing earlier availability of capital as well as the flexibility to use TRZ funds to pay for any transportation project, including projects off the State highway system. However, municipal bond financing entails significant transaction and financial (interest) costs because of the risk associated with the real estate market.

SIBs are a revolving fund established and operated by States. SIBs provide funds to local governments via direct loans and credits to pay for transportation projects. SIB funds are a mix of Federal and State funds. In most cases, SIBs offer low transaction costs and interest rates(10).

Under this option, the local government may seek long-term debt from the State using future TRZ revenue as collateral. This option has the benefits of earlier availability of capital coupled with much lower transaction costs and highly advantageous financial (interest) costs. However, SIB loans may entail competition with other local governments for limited funds. Finally, it is important to note that if Federal funds are used to establish the principal for the loans, the use of SIB funds is limited to projects that are eligible for funding under Title 23 of the U.S. Code. This usually means that a project should be classified as a Federal-aid highway above rural minor collector and included in the statewide transportation improvement plan.xxxvii

Some municipalities in Texas have become more creative in identifying financing options for TRZ revenue. For example, the Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2 project presented in Chapter 6 as a case study is a project that relied exclusively on local entities and local funding(11). Two local governments, the Town of Horizon City and El Paso County, partnered with a regional agency, the Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority (CRRMA), to fund and finance the project under a unique financing arrangement. A detailed description of this arrangement is presented in Chapter 6.

First, El Paso County and CRRMA signed an interlocal agreement providing CRRMA with access to the county’s vehicle registration fee (VRF) revenues to issue bonds and tasking it with developing (designing and building) a slate of projects throughout the county(12). Next, Horizon City signed a three-party interlocal agreement with El Paso County and CRRMA(13). The agreement provided for the development and financing of Horizon City’s local share of the Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2. The agreement committed CRRMA and El Paso County to fund the Horizon City’s share of project costs using county VRF proceeds. In turn, Horizon City committed to repay CRRMA principal and interest using TRZ revenues over a period of 18 years and to acquire the right-of-way for the project. The county funded its share of the project using the VRF revenues. Finally, CRRMA served as the vehicle to issue bonds backed by the county VRFs, as well as the clearinghouse to reimburse the county for the portion of the VRFs using revenues from Horizon City’s TRZ (11). This financing plan had two significant benefits.

First, Horizon City avoided issuing its own TRZ revenue bonds, which would have been more costly because of the risk associated with the real estate market. Second, Horizon City did not need to pursue a Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) SIB loan, which would have delayed the project due to the Federal review process(11).

iv Texas Transportation Code § 222.105–111

xThe Texas Attorney General cites article VIII, section 1(a) of the Texas constitution. See letter from Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton to Representative Joseph C. Pickett dated February 26, 2015: https://www2.texasattorneygeneral.gov/opinions/opinions/51paxton/op/2015/kp0004.pdf

xxx Utah Code § 11-13-227

xxxi Utah Code § 11-9A.

xxxii Utah Code § 17-27.

xxxiii Utah Code § 59-12

xxxiv Utah Code § 59-2

xxxv Aldrete, R. (2019, August 22). Transportation Reinvestment Zones [PowerPoint slides]. In Federal Highway Administration EDC-5 Value Capture Webinar: Value Capture Incremental Growth Techniques and Case Studies. Retrieved from: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/pdfs/value_capture/capacity_building_webinars/webinar_082219.pdf

xxxvi The incremental growth nature of TRZ revenue flows also means that in order to adequately serve debt commitments acquired for the project, local governments may be forced to supplement TRZ revenue from general revenue funds in order to meet payments in the early years. Over time, this situation would reverse as annual incremental revenue grows and exceed annual debt service commitments.

xxxvii 23 USC 610(f)).