U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

|

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-06-095

Date: May 2006 |

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a broad view of the planning-level activities recommended for the successful development of CFA plans and procedures. Many of these planning-level activities should take place at a regional level before developing plans and procedures for a specific corridor. Collaboration and coordination among regional stakeholders on regional-level policies, agreements, operational strategies, and funding priorities will set the stage for successful corridor level plans and procedures. In addition, this chapter provides a corridor-level framework for the entire life cycle of planning, deploying, and operating plans and procedures for coordinated operations on a single corridor. Upon reading this chapter, the reader should have a good understanding of the importance and benefits of planning for CFA operations.

This chapter provides a top-down approach to the subject by first focusing on the regional-level planning and coordination activities recommended for corridor management and then introducing the corridor-level framework for corridor management. This corridor-level framework will be explained in more detail in the next chapter, chapter 3.

While an agency could make the case for delving right into the development of corridor management plans and procedures, this chapter suggests that the chances for success will be much higher if some initial planning and coordination is done upfront. Further, the chances for success are even higher if this coordination and collaboration is first initiated at a regional level before filtering down to planning for a specific corridor. In terms of corridor management, taking a regional perspective means developing consensus among regional stakeholders through policies, procedures, agreements, strategies, and priorities for the entire region that will expedite the development of plans and procedures for individual corridors.

"Regional operations" means putting the available operations elements together into an integrated package that focuses on maximum system performance from the users' perspective. The critical integration elements among the regional stakeholders are:(9)

The next section discusses the planning and coordination activities related to corridor management that should be done on a regional level. Section 2.4 introduces a system engineering framework for systematically developing and operating CFA plans and procedures for an individual corridor. The framework will be presented in more detail in the description of the corridor level framework in chapter 3.

Today's realities require recognition of the constraints imposed upon further expansion of the highway network, particularly in metropolitan areas, and that maximization of system efficiency and system preservation need to become higher priorities. Regional planning for operations is a part of this new reality, and it must be assimilated into the broader metropolitan planning process undertaken by metropolitan planning organizations.

|

This process provides a systematic approach to improving regional traffic management, a portion of which is corridor traffic management. |

While local metropolitan policymaking organizations currently exist with their own local agency interactions and relationships, to achieve a broader vision of the transportation system requires building new processes and procedures with a regional focus. It is the regional transportation planning process that brings regional collaboration and coordination to bear on operational issues. This process provides a systematic approach to improving regional traffic management, a portion of which is corridor traffic management.

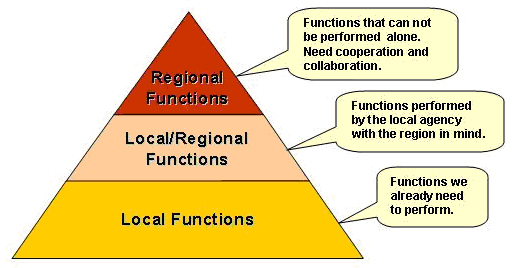

The first step in developing CFA operations is understanding that a corridor mindset requires a regional perspective and function. Figure 3 illustrates how certain functions can only be executed with cooperation and collaboration at the regional level, not at the local or individual agency level. Local agencies cannot achieve coordinated operations based on their individual actions.

Examples of regional functions include:

Figure 3. Chart. Relationship between regional and local functions.(10)

Regional-level focus provides multi-agency coordination for many aspects of the surface transportation system, fostering freeway mobility, arterial mobility, and traveler information. Regional coordination is also a primary factor in encouraging multi-agency sharing of data and resources.

Five major elements, shown in figure 4, form a collaboration and coordination framework on which to build sustained relationships between all affected agencies and stakeholders and create strategies to improve transportation system performance. The framework creates structures through which processes occur that result in products (e.g., a regional corridor traffic management plan as discussed in the next section). A commitment of resources is implied to support initiation and sustaining of regional collaboration and coordination and for implementing agreed upon solutions and procedures. The entire effort is motivated by a desire for measurable improvement in regional transportation system performance.(11)

Figure 4. Chart. Elements of regional collaboration and coordination.(11)

The objective of the collaboration and coordination framework is to help institutionalize working together as a way of doing business among transportation agencies, public safety officials, and other public and private sector interests within a region. The framework is therefore appropriate for developing a CFA operations program. Depending on the state of operations in the region, corridor operations can either build upon an established collaboration and coordination framework or the collaboration and coordination framework can be used as an aid to develop the interagency partnership necessary for a successful corridor operations program.

A collaboration and coordination framework is important because existing institutional structures create barriers that make collaboration and coordination difficult. These barriers include resource constraints, internal stovepipes in large agencies, and the often narrow jurisdictional perspective of governing boards. The framework is intended to guide operators and service providers in overcoming these institutional barriers by establishing a process that has been shown to be successful in facilitating cooperative relationships.

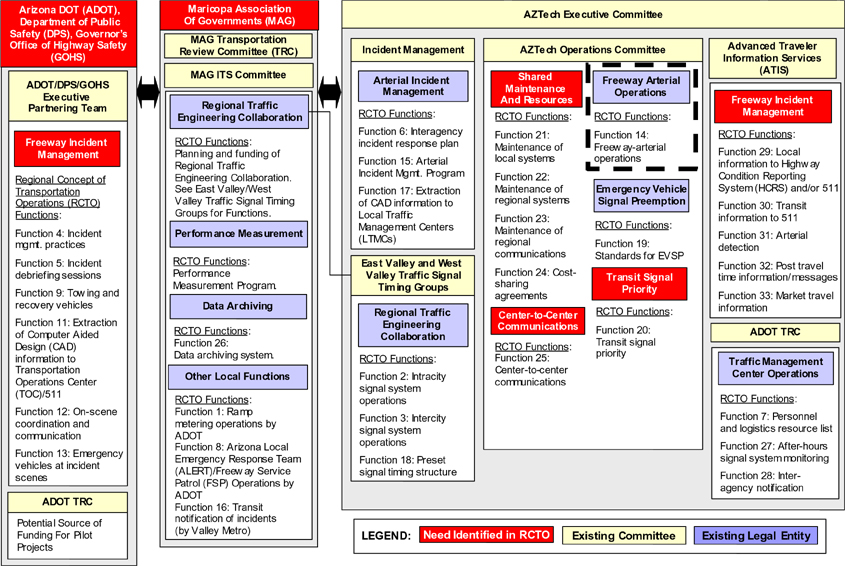

An example of developing a regional-level structure to overcome these traditional institutional limitations is shown in figure 5. This figure is from the Maricopa Association of Governments (MAG) Regional Concept of Transportation Operations, which provides the vision and goals for regional operations around Phoenix, AZ as well as a high-level view of the initiatives and performance improvements that collaboration and coordination may achieve. This figure shows the relationship between local and regional functions developed by the MAG for its region and is illustrative of how a regional focus was established using existing agencies. Note that a Freeway-Arterial Operations subcommittee has been established within this structure. This subcommittee organizes and coordinates the regional efforts for corridor management with the local agencies.

Another example of a regional-level structure is a regional operating organization (ROO), which consists of traffic operations agencies, transit agencies, law enforcement, elected officials, and other operations agencies focused on the operation and performance of a regional transportation system. A ROO works to ensure interagency coordination of resources and information across jurisdictional boundaries. It builds partnerships and trust among agencies to improve their productivity and performance, creating a more responsive system to temporary capacity deficiencies. ROO member agencies may, for example, share traffic signal timing plans, coordinate planned strategies and resources for managing travel, conduct public outreach, and participate in interagency training.

Figure 5. Chart. Example of integrating regional and local processes.(10)

The first step in developing a corridor management plan is to leverage or build on the regional planning process. The goal of planning at the regional level is the development of a comprehensive plan for coordinating freeway and arterial operations throughout the region. Such a plan, developed or supported by key stakeholders in all affected agencies, would be more likely to gain the approval of key decisionmakers responsible for funding decisions in the region. Once funding and resources have been harnessed, plans and procedures for specific corridors can be developed.

The first step in developing a corridor management plan is to leverage or build on the regional planning process. |

The objective of a regional corridor traffic management plan would be to address issues and barriers related to coordinating freeway and arterial operations that are best dealt with at a regional level before developing and implementing specific plans, strategies, and procedures within specific corridors. In other words, it may be possible to solve a host of issues globally for an entire region rather than cause unnecessary repetition by addressing the issues individually for each specific corridor.

Operations issues that can be addressed and resolved at a regional level through policies, agreements, and plans include:

In addition to developing common regional-level operations policies, agreements, and plans, a regional corridor management plan could identify and address a number of other issues:

The process of putting together a regional corridor management plan will be highly dependent upon existing programs and relationships among local agencies. Figure 5 in the previous section illustrates how one region created a region-based institutional structure that could be readily harnessed to develop such a regional corridor management plan. Each region will have to tailor their approach to the local institutional relationships and structures.

While a formal regional-level plan as suggested in this section is not a requirement before developing plans and procedures for individual corridors, there are benefits to developing a regional plan, such as:

Some smaller regions may determine that the upfront cost of preparing a formal regional corridor management plan may outweigh the benefits listed above. For example, a region with one corridor that, both in the near- and long-term, would justify CFA plans, may not need a formal regional corridor management plan and could proceed directly to developing plans and procedures for that individual corridor.

After developing a regional corridor management plan, the region would have institutional structures in place, consensus by regional stakeholders, policies and plans to support corridor management, a prioritized list of corridors warranting individual plans, and the resources identified to develop and operate individual corridor implementation plans. The next section discusses a recommended framework for development and operation of individual corridor implementation plans and procedures.

A process roadmap, or framework, was developed to facilitate the life cycle (planning, design, operations, and maintenance) of CFA operations for an individual corridor. This framework is recommended for individual corridors after addressing regional-level issues identified in section 2.3. Because corridor traffic management is typically fragmented due to the institutional make up of the agencies involved in corridor traffic operations, the framework provides a process to overcome the institutional seams that inhibit coordination and collaboration.

|

The framework provides a process to overcome the institutional seams that inhibit coordination and collaboration. |

The framework is scalable based on the complexity of the corridor and required operations strategies. For smaller corridors, some steps may not need to be formally addressed (e.g., a formal evaluation of operations strategies may not be necessary when there is only one feasible strategy). For larger, more complex corridors, formally going through each step in the framework may be necessary to ensure consensus is achieved by stakeholders, to provide a roadmap through the entire life cycle of the project, and to help to identify and address major problems before it is too late (i.e., already in the implementation phase).

The coordinated freeways and arterials framework is composed of the following elements (a graphical version of the framework is presented in chapter 3):

It should be noted that the framework is cyclic, because the process often requires iteration between steps to resolve competing issues. For example, an operations strategy may be chosen for evaluation. Upon close consideration, the strategy may require more resources than are available, resulting in the reconsideration of alternative strategies more consistent with the available resources.

The steps in the framework are grouped into four categories: getting started, decisionmaking, implementation, and continuous improvement. The remainder of this section presents a high-level discussion of each of these four categories. The next chapter, chapter 3, discusses each of these steps in more detail.

Step 1 is to define the problem. This may occur either through a formal performance monitoring process that is part of a regional planning process or as the result of an obvious operational problem such as traffic backing up onto a freeway due

|

The success of the project is a direct result of the ability of a variety of institutions, agencies, and affected parties to gain consensus, have regular contact through meetings or other communication, and work within the context of other regional entities. |

to an arterial traffic signal. The definition of the problem in the broadest sense should actually begin at the regional planning and coordination stage discussed in the previous section. At the regional level, problems are identified at a minimal level of detail as part of a planning and programming function. What may be a problem to one agency may not be a problem to another; therefore, it is important to discuss and gain consensus on the extent and severity of the problem to be addressed.

This is where Step 2 comes in, which is to assess institutional considerations. A CFA framework can create a bridge for agency structures to address an identified problem in a manner that all affected stakeholders can support. Part of overcoming institutional isolation is establishing a structure, such as a working group composed of various representatives from the affected agencies, early on to guide the entire process. The structure, whether an ad hoc group or formal committee, should consist of the broadest constituency of stakeholders possible. Participants should be representative of all agencies and parties involved in the planning, design, operation, or maintenance of the plans and procedures (e.g., planners, engineers, traffic managers and supervisors, TMC operators, and maintenance personnel), as well as those directly impacted by the plans and procedures (e.g., law enforcement, emergency services, transit operators, special event centers, and major employers). The size of the group should be commensurate with the size and complexity of the project. Overall, the success of the project is a direct result of the ability of a variety of institutions, agencies, and affected parties to gain consensus, have regular contact through meetings or other communication, and work within the context of other regional entities.

Once the structure for the stakeholders has been agreed upon and developed, it will be their responsibility to identify the goals, objectives and performance criteria for the corridor, step 3 in the process. Ideally, the goals and objectives established will be directly related to the problems identified in the first step. If the problem was identified broadly, it will be the responsibility of the stakeholder group to examine the problem and develop a more detailed assessment of its nature. The goals will be broad statements of the desired outcome once the problem is resolved. The objectives will be specific statements of what will be achieved in support of the goals (e.g., to reduce incident-related delays by 10 percent), and the performance measures identified will represent specific measurements that will be used to assess the goals and objectives (e.g., vehicle-hours of delay during the a.m. peak travel period). Performance measures should include metrics that users of the transportation system experience directly, such as traveltime between points.

Step 4 in getting started is to develop a corridor concept of operations. The corridor concept of operations is a document, either formal or informal, that provides a high-level, user-oriented view of operations in a specific corridor. It is developed to help communicate this view to other

|

The corridor concept of operations is a document, either formal or informal, that provides a high-level, user-oriented view of operations in a specific corridor. |

stakeholders in this process, such as the interested public, and to solicit their feedback. The final document should describe the goals, objectives, and performance measures of the corridor agreed upon by the stakeholder group. It should also provide a description of the existing corridor conditions, geometrics and traffic control devices, operating practices and policies, and ITS technologies and capabilities. It should also describe at a high level the operational scenarios (the traffic conditions during a given operational deficiency) when strategies, plans, and procedures are needed and the high-level strategies that can address the problems during these scenarios.

Decisionmaking starts with step 5 and requires identification of detailed operations scenarios for the corridor, which allows the process to move toward the selection strategies. While an example of a high-level scenario may be a full closure of the freeway during an incident, a more detailed scenario would be a full closure of the northbound direction of the freeway from Mileposts 15 through 20 for more than 2 hours. Based on this scenario, a number of operations strategies should be identified that may mitigate this potential cause of congestion. The types of strategies that are appropriate within a corridor management context include:

While many strategies may be easily identified, Step 6 is to evaluate and select the most appropriate strategies for each scenario. The assessment of strategies can vary from simple, pragmatic assessments to detailed traffic microsimulation studies. The method used should be appropriate to the complexity of the alternatives and the cost of implementation. The evaluation criteria should also be representative of the goals and objectives of the local area.

The final step in the decisionmaking phase of the CFA operations framework, step 7, is to develop a corridor implementation plan, which provides all the information necessary to proceed with the implementation phase. The corridor implementation plan may be a formal document that represents the sum total of all the work that has been undertaken up to this point, summarizing the identified problems; the goals, objectives, and performance measures; the corridor concept of operations; and the selected operations strategies for various corridor scenarios. When describing operations strategies, details such as capital and operating costs, potential programming priorities and scheduling, infrastructure needs in support of the strategies, and descriptions of maintenance procedures and costs can help create a valuable blueprint for the remainder of the project.

The implementation phase consists of design and development, deployment, and operations and maintenance. Step 8, design and development, translates each of the various projects included in the corridor implementation plan into executable project operations plans. Operations plans would be developed only at a high level in the corridor implementation plan, while in this step the individual operations plans would be fully developed. For example, the corridor implementation plan may identify a light diversion signal timing plan as an operations strategy. In the design and development stage, the exact signal settings in the timing plan would be determined, the specific individual(s) authorized to implement the plan would be identified, and details of how the plans would be implemented would be agreed upon. The design of needed infrastructure to support the operations strategies, such as deployment of an arterial DMS, would also be completed at this stage of the process. Any needed interagency operating agreements would also be finalized during this step.

Step 9, deployment, comprises the construction of infrastructure, signing interagency agreements, and "turning on" needed software or communications equipment. There could be many factors involved with a multi-agency, multifaceted deployment, so patience and dedication is necessary to ensure a successful project.

Step 10, operations and maintenance, is perhaps the most important in the process. Stakeholders whose primary responsibility will be to activate and operate operations plans should be involved early in the process of developing operating plans and procedures. These individuals will not only provide valuable insight into operations and maintenance processes, but also have a clear understanding of the roles and responsibilities of operations and maintenance personnel during the various scenarios. They will also be able to ensure that plans are operating at maximum efficiency and reliability.

The continuous improvement process, reflected in step 11, is never ending. As the system is being operated and maintained, it must be continually monitored. The monitoring process determines whether the actual performance of the system matches the goals and objectives of the project. If the system is not solving the problem identified in Step 1, then modifications should be made to better address the problem. This is, in effect, another cycle of problem identification, identification of improvement strategies, evaluation, prioritization, design, deployment, operations, maintenance, and so on. More detail is given in section 3.13 on when iteration through the process is necessary, and to which step in the process iteration should occur. Without such a process, the corridor (and the overall system) will fail to perform at optimum effectiveness and efficiency.

This chapter presented a broad view of the planning-level activities recommended for the successful development of CFA operations. The planning process was examined at a regional level and then at a corridor-specific level. It is only after understanding these levels that meaningful corridor sensitivity and analysis can be initiated. The CFA framework introduced in this chapter, is described in more detail in the next chapter. Utilizing a consistent framework insures a repeatable, stepwise process. Thusly, process, appropriate technologies, and deployable solutions are the primary focus for the remainder of this document.

FHWA-HRT-06-095