U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Attachment 1: Project Funds Management Guide for State Grants

Project Funds Management Guide Attachments - 1 | 2 | Q&A

The purpose of this guidance is for Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) division offices, State Departments of Transportation (DOT),1 and other direct recipients and their subrecipients to focus their efforts on establishing and executing sustainable and proactive procedures for timely funds management of all FHWA authorized projects. Such procedures are essential to ensure Federal obligations are adjusted to align with the project’s current cost estimate and that incurred costs are billed promptly and accurately.2 This guidance defines the expectations and requirements for:

Sound funds management entails efficiently advancing projects from authorization of the scope of work and obligation of funds to closing the project, while ensuring proper use of available Federal funding for purposes authorized or in furtherance of necessary expenses to carry out such purpose. This guidance discusses the steps that must be taken to ensure the recipient complies with applicable Federal laws and regulations for authorizations and obligations of all projects authorized through FMIS.3 For innovative financing or alternative contracting methods, some alternative considerations may be necessary and are outside the scope of this guidance. Deviations from this guidance should be documented within the project agreement or in other documented sources supporting the project.

Funds management requirements and procedures are based upon a number of Federal authorities and sources. These sources include provisions from the U.S. Code (U.S.C.) titles 23, 49 and 31, Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) titles 23 and 49, 2 CFR parts 200 and 1201, and guidance provided in the Government Accountability Office (GAO)’s Principles of Federal Appropriations Law (also known as the Red Book). This guide is an effort to synthesize and combine these multiple sources into a consolidated guidance document to improve Federal-aid funds management. This guidance provides recommendations and best practices for funds management. Any requirements discussed are imposed by statute or regulation.

The proper authorization of a project4 is an important early step in sound funds management. A proper authorization includes a clearly defined scope of work for the applicable phase (e.g., preliminary engineering (PE), right-of-way(ROW), construction, etc.) with sufficient funds to accomplish that work recorded in the project agreement and the period of performance to accomplish that work. The funding authorized in the project agreement for the applicable phase must be supported by a documented current cost estimate aligned with the eligible work being completed.5 The agreement must also have an identified period of performance (e.g., project start and end date in the agreement) for the scope of work being authorized.6

The FHWA is required to authorize all7 federally funded projects, including those using advance construction (AC) provisions, before work is started8 (e.g., incurring costs).9 The Federal share is established when the funds are obligated on the project for the phase or activity placed under agreement.10 Federal funds cannot reimburse any otherwise eligible cost incurred prior to the authorization of the project or applicable phase of work per the phase effective authorization date recorded in FMIS, unless specifically authorized in statute, regulation, or approved under procedures set forth in 23 CFR 1.9(b).11

Under 23 U.S.C. 106(c), the State may assume many responsibilities of the Secretary, however project authorization and obligation of funds requires that the FHWA enter into an obligation on behalf of the Federal government under the recording statute.12 Therefore, FHWA remains responsible for ensuring (1) a project agreement is properly established which documents the scope of work being authorized, (2) the funds identified are eligible for those activities, (3) the project has an appropriate schedule (period of performance), and (4) the applicable maximum Federal share is not exceeded in the agreement. The project agreement is a contractual agreement between the State and the Federal government. In submitting the agreement for approval, the State is certifying that the applicable Federal prerequisites that have been assumed by the State have been met, all other requirements will be completed, and the information contained in the agreement is accurate. The FHWA addresses stewardship of the State assumption of responsibilities through a risk based stewardship and oversight process.

The FHWA may authorize a project submitted by the State DOT once applicable Federal and State laws and regulations have been met.13 Each project, or phase of a project, should be supported by information demonstrating that it is ready to advance, such as inclusion in the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), project design schedule, contract letting schedule, etc. Division offices should only authorize the work that is “ready to proceed,” which, it is recommended, typically anticipates the State DOT issuing a request for proposals, qualifications, and/or bids within 90 days. Authorizing a phase of a project before it is ready to advance is a significant cause of project inactivity. If the State DOT requests to authorize a project before certain Federal requirements have been met, specific conditions (known as a conditional authorization) should be placed in the project agreement to address those specified Federal requirements. Authorization is a key element in FHWA’s internal control mechanism to ensure Federal and State laws, regulations, policies, and procedures have been met before eligible costs are incurred.14 The division office’s and State DOT’s Stewardship and Oversight Agreement and applicable standard operating procedures should outline approvals and actions required for Federal authorizations.

If a State DOT elects to use the same project agreement for more than one phase of work (i.e., use one Federal-aid project number), each phase should be authorized and funds obligated only when that phase, activity, or contract is ready to proceed. Authorizing preliminary engineering (PE), right-of-way (ROW), and construction costs at the same time typically should not occur as this is prematurely authorizing phases of work not yet ready to proceed. For example, to authorize construction, 23 CFR 635.309 requires that the plans, specifications, and estimate be approved. Therefore, it is not appropriate to authorize PE and construction at the same time except where the activities are combined, such as a design-build authorization. When the next sequential phase of a project is ready to proceed, the project agreement may be modified to include the additional costs, the phase authorization date, and appropriate adjustment to the project end date. There are other procurement methods, such as Construction Manager/General Contractor (CMGC), that may result in two or more phases being authorized concurrently (e.g., final design and construction).

Authorizing each phase of work and the funds necessary for that phase at the time it is ready to proceed helps ensure the expenditure of Federal funds is readily traceable to the applicable activity and that applicable Federal requirements have been met for each scope of work. As each phase is authorized, when grouped in a single project agreement, the activity in FMIS should be clearly defined in the State/division remarks fields. Each authorized phase of the project needs specific deliverables to establish a reasonable cost estimate and the end date of the authorized scope of work. For example, a deliverable for the PE phase of a project may be the NEPA document and the cost estimate authorized and the end date represent the amount necessary to complete that work. For work to be accomplished under on-call or indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) consultant services contracts,15 the project agreements should be authorized only based on the specific deliverable, (e.g., approved task order) related cost and time period for that deliverable, as provided in the accompanying statement of work, or task order placed under agreement with the contractor to be completed. These on-call contracts should not be based on the upper funding limit or contract open time period. Note this does not include typical milestone approvals that may be needed for the contractor to move on to additional work. On-call contracts are not generally authorized for construction activities.16

The project agreement will document the Federal share of the eligible cost of the project or phase of work.17 The scope of work should convey the project location and work to be completed.18 The total project cost must account for all costs for the authorized work from all sources—Federal, State, local, private, and donations, and non-participating costs.19 For example, the total project costs authorized for a construction contract should be equal to the estimated cost of that contract (i.e., the cost listed in the PS&E, including all participating and non-participating costs) and may include documented contingency estimate.20 There should be a direct relationship between source documents and the project agreement total cost. The project agreement does not have to include costs of phases or contracts that are separate and will not use Federal-aid funding.21

Non-participating costs associated with the authorized phase of work may result from ineligible work or a determination by the recipient to not use Federal funds for a portion of the project. The State must have a process for segregating ineligible activities and non-participating charges, which should be readily identifiable to a reviewer not familiar with the project. Non-participating costs should be included in the total project cost for applicable phases and recorded in FMIS. Although the total cost recorded in the project agreement includes non-participating costs, the Federal pro rata share is based only on those costs that are identified as participating.

Each project agreement must have an identified period of performance for the scope of work authorized.22 The period of performance includes both a start and end date, which identifies the period of time when costs can be incurred (work performed) on a project for the authorized scope of work to be eligible to be reimbursed with Federal funds.23

The project end date is an important part of the project agreement because it promotes effective internal control by recipients in monitoring and closing projects on a timely basis. A project end date is a key internal control from three monitoring standpoints. First, it prompts the State DOT to evaluate scheduled final cost and release (or deobligate) unused Federal funds within 90 days, recovering unexpended balances for other eligible purposes. Second, it establishes the point that no additional costs can be incurred on the project for reimbursement and requiring authorized work to be completed. And third, it prompts the project closeout process.

The project end date should be based on the project’s estimated time to complete the authorized scope of work, must reflect any time needed when other direct project costs may be incurred after the completion of the physical project for those costs to be allowable for reimbursement, and time needed to satisfy other Federal requirements prior to closure. For example, the project end date should be set based on historic evidence of time typically required to complete the same scope of work as included in the contract documentation. A project end date may include a reasonable and supportable amount of time for finalizing billing documentation and ensuring all Federal and State requirements are met. The basis for determining the project end date should be documented in the State specific project authorization procedures. The project end date does not include future project work activities or phases that are not currently authorized. The division office and State DOT should collaboratively develop a methodology to establish supportable project end dates.

Federal-aid projects are generally authorized by phase—PE, ROW, construction, and other. While PE projects have up to 10 years to advance to ROW acquisition or construction,24 and ROW projects have up to 20 years to advance,25 these eligibility timeframes should not be used to determine the project end date as they are not related to the actual expected completion of those authorized activities. Simply establishing a generalized time period to choose a date at some point in the future, while convenient, is not an acceptable procedure for creating project end dates.

The project end date may be modified when requested by the State DOT for justified project modifications (e.g., adding development phases or construction contract, additional related scope of work, justified delays, or additional applicable activities), as appropriate. The modification must occur before the applicable work is performed to be allowable for reimbursement.26 Each project agreement has one project end date which is modified as activities or phases are added to the agreement.

Work performed after a project end date is not allowable for reimbursement. Modifying the project end date after the fact does not remedy this lapse in the period of performance for work performed during that lapse period. Therefore, it is a best practice to evaluate the project end date anytime a contract is awarded or modified or significant delays occur to ensure the contract performance period is within the project agreement period of performance. Only work performed after the approved modification of the project end date is allowable. For example, a project end date is March 31 but the project has not been completed. On April 15, the State realizes the project was delayed and requires two more months to May 31 to complete and modifies the end date in the project agreement. Project billings for work performed from April 1 to April 15 are not allowable for reimbursement. Work performed from April 15 to May 31 is an allowable cost. These unallowable costs would need to be documented as non-participating for Federal-aid funds.

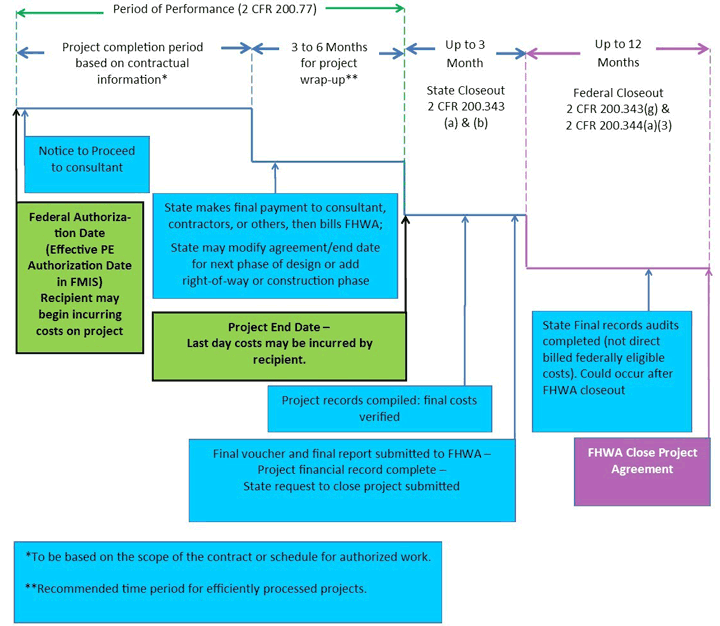

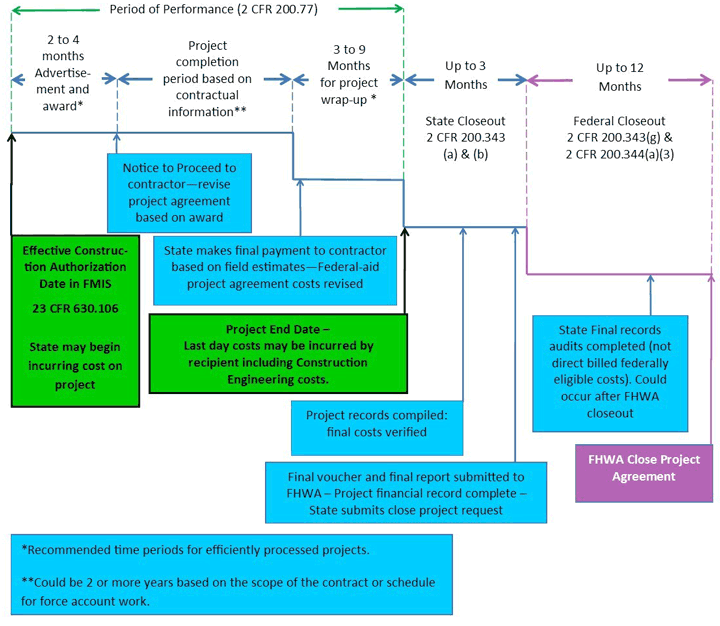

Figures 1 and 2 show example project agreement timelines depicting an agreement start date, period of performance, project end date, and State DOT and FHWA closeout periods. Actions that may occur after the project end date are addressed in later sections. The figures demonstrate recommended timelines to efficiently move projects to project closeout. Suggested timeframes provide 6 to 12 months for a State DOT to complete final voucher and request to close a Federal-aid project after a project is anticipated to be completed (e.g., contractor completes contract). Figure 1 represents a PE project while Figure 2 represents a construction project. Note the final 12 months provided is for the Federal government in the regulation to close the project but is typically not needed by FHWA for Federal-aid projects once the State DOT submits final voucher and requests to close the project.

Figure 1: PE (consultant services) Project Agreement Timeline

Figure 2: Construction Project Agreement Timeline

Project agreements with prerequisite conditions to proceed (conditional approval) should only be used in limited circumstances when determined by the appropriate Federal official to be in the public interest. Such approvals may create a risk that Federal funds may not be expended in accordance with laws and regulations. Such conditions should be included in the project agreement.27 The project agreement should be modified when such conditions have been fulfilled. The State and division must ensure all applicable Federal requirements are met prior to the activity occurring. An example of a conditional authorization is when the State DOT demonstrates that Federal requirements will be met before a project is awarded, such as right-of-way clearance, but a need has been demonstrated to authorize the project prior to conditions being met, and delay of the project agreement would negatively impact the project schedule. Conditional approvals should not be made for the purpose of reserving funds before the project is ready to proceed.

An obligation is a definite commitment of the Federal government that creates a legal liability for payment based upon a documented and binding agreement between a Federal agency and an authorized grant recipient or other legal entity (including another Federal agency).28 This documentation must support that the obligation is for purposes authorized by law. An AC authorization is not an obligation, but is an agreement authorized pursuant to 23 U.S.C. 115 that may mature into a future obligation associated with State incurred expenses for an authorized project pursuant to this unique provision.29 An AC authorization is administered in the same manner as under a typical project agreement, except that there is no obligation of Federal funds and the Federal share is not established.30 The Federal share, whether stated as a percent or as a lump sum, is established for the newly obligated Federal-aid funds at the time of the AC “conversion” or “partial conversion” to an obligation of Federal funds for the prior authorized State incurred costs. The Federal share in the project agreement needs to be validated at the time of conversion based on fund type, eligibility, and classification of the Federal-aid highway.

A proper obligation of Federal funds or AC authorization occurs when the project agreement:

An obligation of funds is a commitment by the Federal Government to reimburse eligible and allowable costs. Appropriations law requires obligations to be recorded within their period of availability.35 Under 23 U.S.C. 118, certain Federal-aid funds released by modification of the project agreement or final payment after the period of availability has ended may be reobligated within the same fiscal year that the deobligation occurred.36

As previously stated, recording an obligation before the project is ready to proceed (based upon documentation, project schedule, and funding) is not allowed except under the mentioned conditional approvals. Examples of unallowable practices include:

Deobligating funds from a recorded obligation solely to release them for another purpose, replace them with other funds, or use AC (commonly referred to as “reverse AC”) to replace the original obligation is not allowed unless authorized by statute.38 Examples of unallowable practices include:

When the project agreement does not reflect the total cost under the conditions described above, costs incurred are unallowable for reimbursement because funds to cover such costs are not properly authorized.40

Project funds management by the FHWA and State DOT integrates monitoring of obligations and project performance schedules.41 Monitoring is an internal control component used to assess the quality of project administration over time and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.42 Ongoing monitoring is a primary component of proactively managing obligations to prevent the obligation from becoming inactive, and to help prevent fraud, waste, and abuse. Project agreements and obligations should reflect the projects in the applicable STIP and other State scheduling references, such as contract letting schedules and contract terms. Division offices and State DOTs should manage and adjust obligations to reflect the current cost estimate.43 If the State DOT does not adjust obligations to reflect the current cost estimate in a timely manner, the division office may unilaterally deobligate unsupported funds (discussed below). Further, if the authorized project cost is not adjusted to take into account significant increases and changes to the project,44 those costs are not under agreement to be reimbursed with Federal funds.

Standard operating procedures (SOPs) are an important internal control tool that can assist division offices and State DOTs with implementing effective project funds management, adequate project delivery systems, and other aspects of stewardship and oversight agreements. Documented SOPs facilitate consistently applied stewardship and oversight to ensure appropriate governing policies are in place particularly when many responsibilities have been assumed by State DOTs through such agreements. Division offices and State DOTs should maintain SOPs describing the responsibilities associated with monitoring all federally funded projects and the frequency with which their respective responsibilities must be carried out.45 SOPs that are kept up-to-date and consistently followed, coupled with effective management controls, minimize the risk of regulatory non-compliance and financial irregularities.

Monitoring should include understanding a project’s schedule to ensure the project is progressing appropriately.46 It is recommended to advertise a project (or a request for proposals or qualifications issued) within 90 days of authorization. If the project is not progressing within a reasonable timeframe (e.g., not being advertised and awarded), the State DOT should withdraw or, if appropriate, close the project, applicable phase, or scope of work. Once a project or phase is withdrawn, any additional costs incurred may not be billed for reimbursement for the corresponding work. Such activity may be reauthorized when it is ready to proceed. Once reauthorized, costs may be incurred after reauthorization and may be reimbursed.47

Regularly billing a project to expend obligations and consistently updating project agreements to align with the current cost estimate are consistent with good funds management. If these activities do not occur at least annually, then the project will likely be inactive without sufficient justification. These activities help to ensure FHWA has accurate financial reports and there is a clear accounting of balances available, obligated and expended from the Highway Trust Fund.

Effective monitoring practices include periodic reviews by the State DOT to adjust or modify the project agreement to reasonably reflect the current cost estimate. Adjustments to recorded obligations (or the amount authorized as AC) must be supported by documentation of changes in the project cost and must maintain the Federal share as originally authorized48 or adjusted at bid award.49 If the precise cost related to a pending obligation is not known, the funding amount must be based on the best available information. As more precise information becomes available, the State DOT is required to adjust the obligation to match the current estimate. If the project is properly authorized, additional costs that occur during progression of the project (e.g., cost overruns, eligible costs identified during audits, within scope cost increases, and changed field conditions) may be eligible and allowable for Federal reimbursement. The project agreement should be modified as soon as practical to reflect such costs when they are identified.

If a State desires to maximize flexibility on the amount and type of Federal funds to apply to a project, the project should be authorized as an AC project. As noted, the Federal share or the lump sum amount of an actual obligation of Federal funds for authorized work should not be changed after the project agreement is approved except at contract award. An AC authorization provides the State flexibility on type and amount of Federal funds used for authorized work. Currently, only the emergency relief and the high priority projects programs allow one fund source to be replaced with another. An AC authorization must be treated the same as a Federal-aid obligation with respect to meeting all Federal regulatory requirements and policies except there is no commitment of Federal funds.50 The potential Federal share is identified in the AC authorization up to the maximum for the program funds identified but may be changed at the time of obligation for the funds selected.

Periodic reviews also include managing inactive obligations (no expenditure activity in the previous 12 months or longer)51 and monitoring the progress of projects to the next phase of work, as appropriate. When managing inactive obligations, division offices should review billing activity to ensure reimbursement requests are proper and are not devices solely to keep a project from becoming inactive (such as a token payment). If monitoring indicates that unsupported, ineligible, or unallowable costs are being billed, the division office should initiate immediate corrective actions. Recoveries of improper payments are due to the Federal government within 90 days.52

Additionally, expenditures for PE53 or right-of-way54 projects are subject to repayment provisions if the project does not progress to the next phase of work. State DOTs and division offices should monitor PE projects to ensure they progress to the next phase of work within 10 years from the date of authorization. State DOTs and division offices should monitor right-of-way projects to ensure they progress to construction within 20 years from date of authorization. For example, division offices may review PE projects that have been authorized at 3 years and 7 years after authorization to ensure work is progressing according to schedule. At 10 years, such projects should be reviewed to confirm right-of-way or construction has proceeded and if not, to determine if a time extension is warranted, or if payback of Federal funds is required.

Adjustments culminating in a deobligation of Federal funds must be supported by a documented cost estimate. A deobligation of funds to the level of expenditures should not occur unless supported by a current cost estimate (except as discussed later when a project becomes inactive), as this violates the requirement to have the total project cost of the authorized phase reflected in the project agreement (i.e., in FMIS) at all times. Deobligating Federal funds removes Federal participation for the work that was supported by the obligation, but not yet incurred. Reducing the Federal funds to the expended amount means that any cost incurred after that date cannot be reimbursed because the deobligation removes Federal authorization for further work.55

Project management and monitoring are partially facilitated through the requirement for quarterly testing of inactive projects. Recipients must demonstrate that the obligation for the tested projects remains proper and that the inactivity is beyond the State DOT’s control.56 Causes beyond their control may include delays such as litigation, unforeseen utility relocations, catastrophic events that materially delay the project or unforeseen environmental concerns.

State DOTs are encouraged to include billing requirements in their subrecipient agreements to ensure requests for reimbursement are processed on a periodic basis (e.g., monthly). Lack of timely billing from subrecipients is not a sufficient justification for the inactive obligation.

Utilities and railroad projects have unique allowances for billings up to one year after the actual reimbursable work is completed.57 State DOTs are encouraged to have documented prompt billing processes in their agreements with the utility and railroad organizations to bill as work proceeds. Considering the regulatory allowance for the delayed billings for these types of projects, sufficient justification based on the regulation can be provided for inactive projects of this category. However, States are encouraged to use the regulatory authority provided to them to end billing and reimbursement one year after the work is completed. This provision is also justification to extend the 90-day billing period after the project end date.58

An inactive obligation is proper if it aligns with the State DOT’s documented current cost estimate and the State DOT demonstrates that project activity is occurring that requires the unexpended amount of funds to remain obligated (e.g., an active contract is approved and ongoing). The division office should be satisfied that the State DOT’s justification sufficiently explains the facts and circumstances causing project delays beyond the State DOT’s control and the existing obligation aligns with a current cost estimate.

An obligation is improper if the State DOT cannot provide adequate justification to explain why the project is stalled or is not under contract, and the division office believes the project will not proceed within a reasonable schedule. For example, a consulting services contract that has been put on hold and is not incurring costs may represent an improper obligation. Improper obligations must be adjusted59 to align the Federal funds obligated with the phase of work’s current cost estimate, which may be the current expended amount. The properly documented expended amount is considered to be the current cost estimate if that is all FHWA has been provided by the State to support the costs. An AC authorization should be treated similarly and the project agreement withdrawn if the project will not proceed in an acceptable timeframe. There is limited purpose for zero-dollar project agreements (no unexpended obligations or AC amount) to be left in place and such agreements should typically be closed or withdrawn. Examples of allowable zero dollar projects may be when the project has an approved tapered match and has been fully expended but is still ongoing or a project is fully expended and is going through closeout process.

If the State DOT or its subrecipient has an active contract in place (i.e., has not been put on hold) and is incurring costs to be reimbursed and sufficient documentation of such activity is provided, the funding should not be deobligated below the current contract cost estimate. Also, the division office should encourage the State DOT to notify its subrecipients that the project obligations will be removed if activity on the project is not demonstrated within a specified and agreed upon timeframe.

If the division offices monitoring discloses improper obligations and the State DOT has not acted after notification, the division office has the authority to unilaterally deobligate the project to the current cost estimate.60 A review for project inactivity should begin when a project has been inactive for 9 months. If reimbursements are not processed within the next quarter, the project will be deemed as inactive at 12 months. The division office should work with the State DOT to remedy the inactive status before the project has 12 months of inactivity (i.e., process a claim for reimbursement, withdraw, or deobligate the project). At this point, the division office should initiate remedial action, possibly a unilateral deobligation for projects determined to be improperly obligated.61

Unilateral deobligation is authorized when the obligation is not supported by a documented cost estimate, not adjusted to reflect the current cost estimate, or is considered improper and the State DOT does not act to deobligate the improper amount. The division office must not deobligate funds that are supported by a current cost estimate (e.g., under contract and incurring costs), or if the project is inactive for documented reasons beyond the State DOT’s or the subrecipient’s control.

The division office is required to notify the State DOT in writing that it intends to unilaterally deobligate funds and provide the State DOT with a reasonable opportunity to respond to the proposed action. If the State DOT does not act or respond within the designated timeframe, FHWA may deobligate unexpended obligations to align obligated Federal funds with the current cost estimate. This unilateral deobligation is not permitted from August 1 to September 30.62

The division office should provide a clear explanation in the FMIS Division Remarks explaining why it is taking unilateral action and that Federal authorization is removed for the funds being deobligated. Once the action is taken in FMIS, the division administrator or designee should forward the modified project agreement to the State DOT point of contact to ensure all recipients are aware of the removal of Federal participation for future costs incurred until the work activities are re-authorized as described below.

When FHWA deobligates funds due to inactivity or insufficient support for the estimate or failure to meet Federal requirements, all costs incurred after deobligation are unallowable for Federal participation. For example, FHWA deobligates $1,000 in January from the project’s unexpended amount. In June, the State DOT requests to obligate the $1,000 in a project modification and is approved by FHWA. Any costs incurred by the State DOT (or its subrecipient) between January and June are not eligible for reimbursement because unexpended funds were not under obligation for that activity due to the deobligation during the period when those costs were incurred.

The State DOT submits a request to FHWA to close a project when it determines that all required work or deliverables on the project and all applicable administrative actions (e.g., reporting, final billings, etc.) have been completed. This should occur promptly after completion of the project but not later than 90 days after the project end date. Effective project management requires coordination of activities among all units and functions. Coordination within the division office and among all appropriate State DOT offices ensures a Federal project does not languish as open and inactive due to barriers preventing the closing of the project.63

The recent strides made in managing inactive obligations, positions division offices and State DOTs to realize gains in efficiency and effectiveness with respect to project close-out. Division offices are encouraged to work with State DOTs to establish performance goals and metrics associated with managing the timeliness of their project closeout processes and include them in their written operating procedure(s). These could also be incorporated into FHWA/State DOT Stewardship & Oversight agreements to support established goals and metrics.

Successful project closeout practices noted in the Program Management Improvement Team (PMIT) June 2013 program review include:64

A project is considered complete when the work is accepted and the contractor is released from responsibility on the project by the State DOT (except potentially for warranty provisions) and the State DOT has completed chargeable construction engineering activities. Upon final acceptance of a project by the State DOT (e.g., the contractor is released from contractual obligations on the project and retainage is released, except where warranty provisions disallow), final billing of a project and final documentation for project closeout should be completed soon thereafter. Project final acceptance procedures are based on each division office and State DOT stewardship and oversight agreement and established standard operating procedures.

Final costs must be billed and all obligations expended within 90 days of the project end date (e.g., final voucher) unless an extension of the 90-day period is requested by the State DOT and approved by FHWA.65 An extension of the 90-day expenditure period is not a change in the project end date to continue incurring costs on the project. Projects with an AC authorized balance are not subject to the 90-day expenditure provision if there are no unexpended obligations on the project. Partial conversions of an AC authorization to Federal obligations should be liquated promptly (i.e., within 90 days of the obligation). Once the AC authorization is fully converted to a Federal obligation and the period of performance has passed, the funds must be expended within 90 days and the closure initiated by the State DOT. A token AC authorization amount should not be left on a project to delay closeout requirements.

Project closeout procedures should be initiated when the project has been completed. Unexpended Federal funds should be deobligated at that time to reflect the State DOT’s current cost estimate (total final payment to the contractor, plus anticipated “trailing costs,” such as those associated with State DOT final reviews of project documents necessary for closing out the project). Obligations should not be kept on a project while the State is working through the final audit process, pending appeals for denied claims, or other litigation unless there is sufficient reason to believe a denial will be overturned on appeal. Adjustments to the obligations can be made as necessary if eligible and allowable costs or credits to the project are identified that were incurred before excess Federal funds were deobligated. For example, obligations may be adjusted to include costs from project litigation resolved after project closeout.

Closeout also does not relieve the State or subrecipient of other Federal requirements and project commitments under the Federal agreement. As part of the agreement and use of Federal funds, the State must ensure all Federal requirements have been or continue to be carried out.66

Final project documentation must be completed within 90 days after the project end date unless an extension of the documentation period is requested by the State DOT and approved by FHWA.67 It is good practice to record approval of an extension in the division remarks field in FMIS. The final project documentation that is required to be submitted to FHWA in accordance with the applicable stewardship and oversight agreement also needs to be provided within that timeframe. FHWA should approve closure of projects within one year of receipt and acceptance of the project documentation.68 AC projects should follow a similar schedule but some documentation related to the Federal-aid obligation and expenditure will not be completed until those actions occur as previously noted.

Projects can be closed in FMIS once documentation is collected for retention that supports the project’s costs and compliance with Federal, State, and contractual requirements.69 It is a good practice for a division office to include in the stewardship and oversight agreement a list of documents the State DOT is expected to retain and those items the division office expects to receive for closeout purposes. The closeout process should ensure that all costs incurred and reimbursed by FHWA are documented and any required milestone reports are submitted and/or retained. Attachment 2 includes a list of documents typically necessary to support the financial record and requiring retention for financial purposes by the State DOT.

These records may need to be retained for longer periods depending upon the status of the project in its entirety based on the project definition for NEPA, major project purposes, or to support later phases. Typically, the State DOT retains these records, which are to be made available to FHWA upon request.70

The record retention period for the non-Federal entities for financial purposes is 3 years and begins when the final voucher is submitted in FMIS and required documentation is submitted to FHWA per the stewardship and oversight agreement.71 For an AC authorization, the 3-year retention period begins only after the final conversion of State expenditures to Federal obligation has occurred and actual costs are reimbursed by FHWA for the project planned to be closed. The date the recipient requests to close the project is the recommended date to base record retention period in most instances. If a project languishes during the closeout process, there is a possibility of loss of documentary evidence of costs incurred. If documentation is not available to support a cost, those costs may be determined improper and must be repaid. Records for PE and right-of-way projects must be retained in relation to advancing to the next phase in order to document compliance with applicable payback requirements.

Project agreements may be reopened to increase the obligation amount and provide for subsequent reimbursement if additional eligible costs are identified during an audit process, as a result of an appeal of a contractor claim, litigation, etc. The costs must have been incurred during the period of performance or, in the case of litigation and claims, directly related to costs incurred during the period of performance. The project may also be reopened if ineligible costs are identified during the audit process for which funds must be credited back to FHWA. The record retention period restarts if the project must be reopened for such purposes which adjust the final voucher. Records may be required to be retained for longer periods for other purposes.

Project close out Q&A’s will further elaborate on the requirements of 2 CFR part 200 with additional guidance. Please see the Office of the Chief Financial Officer’s (HCF) December 4, 2014 memorandum and Q&A’s for FHWA’s additional implementing guidance on 2 CFR part 200.

Many types of warranty provisions may need to be considered prior to closing out a project. In most instances, the project should be prepared for closure upon the State DOT’s final acceptance and the contractor is provided final payment. There may be instances where the project needs to remain open with obligations for final payment such as a delayed payment of retention for items in accordance with plant establishment contractual requirements.

Keeping a project open solely due to the existence of a warranty is not appropriate except as previously mentioned. Long-term warranties where periodic evaluation is needed do not justify the project to remain open. Eligible periodic evaluations for warranty purposes may be accounted for separately, such as by setting up a separate Federal-aid project agreement if the State determines it is necessary to charge Federal funds. If a failure occurs on a warrantied project or contractual performance is not met, and the contractor or surety makes payments to the State, the original project must be reopened to account for the Federal share of any credits. If repairs are needed that the contractor is not required to provide under terms of the contract, and the repairs are eligible for Federal funding, the State DOT should request a new project agreement for such work because it is outside the original scope of work previously authorized.

Division offices can consult the Office of Infrastructure for additional guidance on warranties.

FHWA uses the following key terms concerning sound funds management and monitoring. Many key terms relate to the Office of the Chief Financial Officer’s guidance, “Funds Availability and Reobligating Expired Funds,” dated January 17, 2014, which can be referenced for more information pertaining to period of availability.

Advance Construction (AC) - The written authorization within a Federal-aid project agreement without the obligation of Federal-aid funds. All requirements of the project agreement must be met, except the actual recording of the obligation.

Current Cost Estimate – A current cost estimate should reflect the anticipated cost of the project in sufficient detail to permit an effective review and comparison of the bids or proposals received. The estimate before the project begins may be based on historical data from recently awarded contracts, the actual cost to complete the work, or a combination of both. As the project progresses, the cost should be adjusted to reflect any contract changes.

Deobligation – A deobligation is the downward adjustment or cancellation and removal of a previously recorded Federal funds obligation associated with a project. This action reduces the obligation on the project agreement.

Effective phase authorization date – The date recorded in FMIS when a project phase is authorized to begin to incur costs and represents the start date for the period of performance for that phase. The date is either the same as the FHWA authorization 3rd signature or must be supported by authorization in external documentation that the phase met Federal requirements and was authorized to proceed.

Expenditure – An expenditure is the actual spending of money (an outlay) or reimbursement that liquidates in whole or in part a previously recorded obligation; reimbursements are requested by the State DOT or other direct recipient, and paid by the Federal Government, to a project or program for which a Federal award was received. This guidance uses the term expenditure in lieu of liquidation.

Final Voucher – Final voucher is the final reconciliation by the recipient of all the costs included in the project agreement and final expenditure or credit and adjustment of Federal obligations to match project costs is requested. For an AC authorization, final voucher is provided after the recipient makes its final AC conversion to obligation of Federal funds and proceeds to close the project. A modification to the project expenditures after the final voucher changes the date of the final voucher.

Fiscal Management Information System (FMIS) – The system used by FHWA and State DOTs to establish project agreements and record Federal-aid fund obligations. The system is used to record various project related information as part of the project agreement.

Inactive Obligation – An inactive obligation is an eligible transportation project with unexpended Federal obligations for which no expenditures have been charged against the Federal funds within the past 12 months or more.72

Ineligible Costs – Ineligible costs are those costs that do not meet the requirements of a specific program or incidental and necessary for the activity; or those that are otherwise unallowable because of not meeting Federal law or regulation. Ineligible costs may not be considered as non-Federal match.

Internal Control – An internal control is a process designed and implemented to provide an entity with reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of objectives in the effectiveness and efficiency of operations, the reliability of reporting for internal and external use, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

Non-participating Costs – Non-participating costs are costs that will not or cannot be reimbursed with Federal funds. These costs are still part of the total cost of the project and should be accounted for in the project agreement. Non-participating costs could occur because of ineligibility or because the grant recipient determined that the specified items will not be reimbursed with Federal funding. Non-participating costs cannot be part of the required non-Federal matching share.

Obligation – An obligation is an action that creates a legal liability or definite commitment of Federal funds on the part of the Government, or creates a legal duty that could mature into a legal liability by virtue of an action that is beyond the control of the Federal Government. Payment may be made immediately or in the future.73

Period of Performance- The period of performance is the time period when costs may be incurred for authorized work. The effective phase authorization date in the FMIS project agreement is the start date of the period of performance for the applicable phase. The project agreement has one period of performance end date which applies to all phases and is modified as phases and additional work is added to the project agreement.

Project Agreement – The project agreement is the Federal approval document that memorializes that a project has met the prerequisite Federal requirements and that the authorized scope is eligible for Federal participation. The agreement must include the required information and certifications.74 The project authorization date for an applicable phase is set when the third line FHWA signature is completed in FMIS unless a prior date has been recorded via other method. The project agreement typically provides the authorization to proceed for the authorized scope of work.75

Project end date - The final date recorded in the project agreement when the recipient or subrecipient may incur direct costs on the project to be eligible for Federal-aid reimbursement. Also, referred to as the period of performance end date or project agreement end date. Project end date is the applicable field in FMIS.

Proper Obligation – A proper obligation is a commitment of Federal funding, which is supported by documentary evidence in writing of a binding agreement between an agency and another entity (including an agency) for a purpose authorized by law, and executed before the end of the period of availability (except for re-obligations permitted under 23 USC 118(c)).76

Recipient – Recipient means a non-Federal entity that receives a Federal award directly from a Federal awarding agency to carry out an activity under a Federal program.

Start Date – The Start Date is associated with a specific phase of a project and identifies the earliest date FHWA will generally participate in costs incurred on a project. The Start date is recorded in FMIS project agreements as the effective phase authorization date.

Subrecipient – Subrecipient means a non-Federal entity that receives Federal funds from a pass-through entity to carry out part of a Federal program. Subrecipients do not include an individual that is a beneficiary of such program. A subrecipient may also be a recipient of other Federal awards directly from a Federal awarding agency.

Total Project Cost –The total project cost for a project agreement is the total costs for the work under agreement that is supported by specific project estimates and/or active contracts. Total project costs include ineligible or other non-participating costs within those estimates and contracts. It is important to ensure consistent documentation and relationship between the project agreement and the contractual documents and project estimate. The total project cost for this purpose does not include future work that has not been put under agreement. Also, it is not required to include the cost of separate work or contracts that proceeded without the use of any Federal-aid funds. This definition does not apply to meeting other Federal requirements, such as for NEPA purposes or financial plans for major projects.

Unallowable Cost – The term unallowable costs are costs that are determined not to meet Federal law, regulation, or policy, or are not allocable to, or not necessary or reasonable for the authorized project. Such costs may include otherwise eligible costs for the program that did not meet certain process requirements (e.g., not properly authorized) or were determined to be otherwise non-participating by agreement. Examples include a cost that is incurred prior to Federal authorization, after the agreement end date, or after a project is deobligated because of non-compliance with funds management requirements. Unallowable costs include specific costs items as provided in 2 CFR 200 subpart E.

Unilateral Deobligation – A unilateral deobligation is the process whereby, after written notice is provided to the State DOT, FHWA may deobligate project obligations that have been determined inactive or otherwise improper without the State DOT’s signature when certain criteria have not been met.

Withdrawal – A withdrawal removes all Federal participation on the phase of work and no further costs can be incurred for reimbursement with Federal funds.

[1] State DOTs are referenced in this document as FHWA’s primary direct recipient of funding through FMIS. This guidance should be applied as applicable to any recipient of FHWA-administered funds and their subrecipients.

[2] Cost estimates may include a reasonable level of contingency based on documented State practice within the budget and relative risk involved for the cost estimate. That is, the contingency amount may be higher at the start of the project and lower as the project nears completion.

[3] FHWA Order 4560.1C, Financial Integrity Review and Evaluation Program (FIRE), dated April 21, 2014, establishes the FIRE program requirements, including the framework for financial internal control to support an annual certification required by 31 U.S.C. 1108(c).

[4] For this guidance, a project is the FMIS authorized project (typically by phase) and should not be confused with a project as defined in National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) or major project legislation and regulation.

[5] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(3); 31 U.S.C. 1554(b)(2)(E) requires that obligated balances reflect proper existing obligations to support eligible and allowable expenditures.

[6] 2 CFR 200.77; 2 CFR 200.309.

[7] Under limited circumstances, if authorized by statute or regulation, certain costs may be incurred prior to authorization, and be eligible for reimbursement of applicable Federal funds after a project authorization, such as Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act Sect. 1440 At-Risk Project Preagreement Authority.

[8] 23 CFR 630.106(a) & (c).

[9] 23 CFR 635.112(a). Proper authorizations for AC, which constitutes an authorization to proceed without an obligation of funds, must meet all Federal requirements, the same as a fully obligated project except that the obligation of funds may occur at a later date. 23 U.S.C. 115 and 23 CFR 630, subpart G, dictate the requirements and procedures for advancing the construction of Federal-aid highway projects without obligating Federal funds apportioned or allocated to the State. There is no authority provided to waive or delay provisions because the project is authorized as AC.

[10] 23 CFR 630.106(f) allows the State DOT to elect either a percent share of the total eligible costs not to exceed the legal maximum Federal share or a lump sum amount that limits the total amount of Federal funds available for the project. The project agreement should clearly identify which method is being authorized. Project agreements using AC are to provide an estimated share that may be adjusted when funds are actually obligated to the project. Also see HCF memorandum titled “Clarification on Modification of Lump Sum Federal Share - Project Agreement,” dated January 3, 2012.

[11] Federal funds include all sources of funding such as the Highway Trust Fund and General Fund.

[12] 31 U.S.C. 1501(a)(5).

[13] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(2). Example prerequisite regulations include 23 CFR 172, 420.115, 635.309, 710.203, and 710 .307.

[14] 23 CFR 1.9(a).

[15] 23 CFR 172.9(a)(3).

[16] 23 CFR 635.104(a).

[17] The Federal share of eligible project costs is established at project agreement, or the initial AC conversion, using either a pro-rata share or lump sum agreement, as required by 23 CFR 630.106(f) by the detail line. See HCF memorandum, “Clarification on Modification of Lump Sum Federal Share – Project Agreement,” dated January 3, 2012 for more information. Using different Federal shares by detail line in a single project agreement should only occur if the State DOT system can track the variation.

[18] The FMIS User Manual provides more information on properly authorizing a project within the system and what information is to be included in a project header.

[19] 23 CFR 630.108(b)(4) & (5), 2 CFR 200.210(a)(9) & (10).

[20] 2 CFR 200.433 Contingency provisions.

[21] Note, when the “project” defined in the NEPA document will be accomplished through a mix of federally and non-federally funded phases or contracts, any non-federally funded work is subject to certain Federal-aid requirements, such as Buy America requirements in 23 U.S.C. 313(g).

[22] 2 CFR 200.77.

[23] 2 CFR 200.309; For a construction project, such period must include direct costs that are to be billed for construction engineering activities.

[24] 23 U.S.C. 102(b).

[25] 23 U.S.C. 108(a)(2).

[26] 2 CFR 200.309.

[27] 2 CFR 200.210(c).

[28] 31 U.S.C. 1501 defines the documentary evidence requirements for Government obligations.

[29] The AC authorization should represent the estimated Federal share that could be converted to an obligation in the future though there is no requirement to convert the full amount. In addition, the Federal share could be higher if an eligible fund source is available at the time of conversion to an obligation. If the State DOT intends to limit the amount of conversion, that should be documented in the State remarks section of the agreement.

[30] 23 CFR 630.703.

[31] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(3) and 23 CFR 630.108(b)(4).

[32] 23 CFR 630.112(b).

[33] HCF memorandum titled “Tapered Match on Federal-aid Projects” dated December 29, 2009.

[34] FHWA Order M1100.1A outlines the Agency’s Delegation of Authority. Individual offices should also have a delegation of authority document. Also, see HCF memorandum “FMIS Project Agreement Signature Responsibility Guidance” July 30, 2015.

[35] 31 U.S.C. 1502.

[36] Refer to the HCF guidance, “Funds Availability and Reobligating Expired Funds,” dated January 17, 2014, for more information on the reobligation authority for funds from the Highway Trust Fund.

[37] Obligating a project with conditions at year end to ensure the project is not delayed by beginning of fiscal year processes, short term appropriations extensions, etc., are allowable practices.

[38] 23 CFR 630.110(a). Principles of Federal Appropriations law, Volume 2, Chapter 7, Section E.

[39] 23 CFR 630.106(g).

[40] This does not apply to eligible project changes and cost overruns as long as they are timely amended onto the project agreement.

[41] 2 CFR 200.328(a).

[42] GAO Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, September 2014, p. 20.

[43] 2 CFR 200.308(b).

[44] 23 CFR 635.120 may be used as a guide for major changes.

[45] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(4), requires States to have processes in place to adjust project cost estimates at specific intervals such as when a bid is approved, a project phase is completed, design change is approved, etc.

[46] 2 CFR 200.328(a) requires continual monitoring to ensure Federal requirements are met and performance goals are being achieved, such as adhering to the project schedule and budget.

[47] Cost incurred after withdrawal and prior to reauthorization are not eligible for reimbursement without a 23 CFR 1.9(b) approval.

[48] 23 CFR 630.106(f)(1).

[49] 23 CFR 630.106(f)(2). For changes in scope for lump sum project agreements, see HCF memo titled “Clarification on Modification of Lump Sum Federal Share – Project Agreement,” dated January 3, 2012.

[50] 23 CFR 630.705(a).

[51] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(5).

[52] 2 CFR 200.345(a).

[53] 23 U.S.C. 102(b), 23 CFR 630.112(c)(2), Engineering Cost Reimbursement; and FHWA Order 5020.1, Repayment of Preliminary Engineering Costs, dated April 26, 2011.

[54] 23 CFR 630.112(c)(1) explains right-of-way acquisition requirements.

[55] This reduction or removal of authorization does not apply to costs eligible to be adjusted due to project closeout and audit activities or for adjustments to account for within scope increases and overruns that occurred when the project or related work was properly authorized, including as a result of litigation and claims.

[56] See HCF memorandum, “Revised Supplemental Internal Procedures for the Review, Validation, and Testing of Inactive Obligations,” dated December 30, 2013, which prescribes the requirements for monitoring inactive obligations.

[57] 23 CFR 140.922(b) and 23 CFR 645.117(i)(2).

[58] An extension in accordance with 2 CFR 200.343(a) and (b).

[59] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(5).

[60] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(6).

[61] See HCF memo, “Revised Supplemental Internal Procedures for the Review, Validation, and Testing of Inactive Obligations” dated December 30, 2013.

[62] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(6).

[63] Barriers include a “silo effect” due to the lack of communication and notification, missing documentation, uncoordinated audit functions, warranty delays, reobligation challenges, reactive project reporting, and lack of timely funds adjustment. These are discussed further in the Program Management Improvement Team’s Final Project Closeout, Phase 2 Report, issued February 2014.

[64] Program Management Improvement Team report titled “Project Closeout and Inactive Funds Management” issued June 2013.

[65] 2 CFR 200.343(b).

[66] 2CFR 200.344(b).

[67] 2 CFR 200.343(a).

[68] 2 CFR 200.343(g), most projects where the State has assumed responsibilities under 23 U.S.C. 106(c) should typically be closed promptly upon request.

[69] 2 CFR 200.343.

[70] FHWA internal record retention requirements are contained in FHWA Order 1324.1B - FHWA Records Management.

[71] 2 CFR 200.333 defines the 3-year record retention requirement starting from the date of final expenditure report submission. In the Federal-aid highway program, this report is the final voucher; but “final expenditure” cannot occur until all AC is converted and expended.

[72] 23 CFR 630.106.

[73] GAO Principles of Appropriations Law, Vol II, 7-3.

[74] 23 CFR 630.108(b), 23 CFR 630.112, 2 CFR 200.210.

[75] 23 CFR 630.106(a)(2).

[76] 31 U.S.C. 1501(a)(5)(B), (C).