General Liability

WINTER HAZARDS

Happy Holidays!

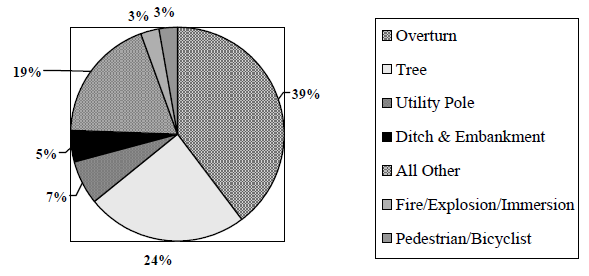

Road design cases continue to be a leading liability loss driver for NYMIR subscribers. Road design cases usually stem from an auto accident where injuries are sustained, and a claim is made against the municipality that owns or controls the road. In many cases, the claimants are individuals who were injured in single-car accidents where the vehicles ran off the road, and hit a stationary object or overturned. The lawsuits typically allege improper design; inadequate signage; failure to correct roadway and roadside hazards and dangers; improper traffic control devices, and unsafe construction zones. Road design cases differ from road maintenance cases. With the latter, claims usually allege failure to provide a reasonably safe roadway – usually improper removal of snow or ice, not cutting back vegetation, failure to remove excess gravel or sand, and improper pothole repairs. The National Safety Council1 indicates there were 12,300 fatal and 290,000 injury accidents as a result of a collision by a motor vehicle with a fixed object – usually a tree, utility pole, guardrail, or abutment. According to the Cornell Local Roads Program, run-off-road collisions accounted for 13 percent of all crashes in New York in 2000 and 27 percent of fatal crashes.2

With many run-off-roads cases, claimants will allege there were hazards adjacent to the road, and a barrier was needed, or the existing one was defective or insufficient to handle the traffic using the road. In other cases, claimants allege that a clear zone or shoulder would have prevented their injuries. At other times, residents – usually property owners who live adjacent to a road – will ask for a guide rail to protect their property. Municipal officials are then faced with an analysis and budgeting process to determine if a rail is needed, and if so, what type of design and in what location.

This risk management bulletin will address the basic issues concerning run-off-road accidents and the methods to establish adequate clear zones adjacent to roads. The March 2004 edition will address the installation of guide rails.

The NYMIR Risk Management staff thanks the engineering professionals at the Cornell Local Roads Program for their assistance in drafting and researching this bulletin. The material was based largely on their Quick Bite publication: Guide Rail. This publication and other material can be obtained by calling 607 255-8033.

Drivers sometimes lose control and run off the road or highway. Most roads bear evidence of such mishaps, such as tire tracks, abandoned hubcaps, and scrapes on trees or roadside barriers. When road engineers and designers plan roads, and when municipal officials evaluate existing roadways, they look for ways to prevent injuries from vehicles leaving the road. Injuries (and tragedies) occur when vehicles collide with roadside hazards, such as trees, signposts, buildings and drainage structures, or when vehicles overturn on an embankment.

Included in the “Other” category in the chart above are guide rails, signs, bridges and piers, parked motor vehicles and other types of barriers.

Fixed objects should be removed or mitigated, and a clear zone established when the objects are solid or large enough to cause serious injuries to vehicle occupants if there is a collision. For example, trees are a common roadside hazard, and usually become problematic when they grow to four inches or more in diameter.

A clear zone is a hazard-free area that gives a driver sufficient room to recover from a mistake. It should be relatively flat and smooth, and changes in grade should be rounded. These actions will help a driver correct a mistake and return safely to the roadway.

The desired width of the clear zone depends on the amount of traffic on the road, the prevailing speed, the cross slope of the roadside and the curvature of the road. The clear zone is measured from the vehicle lane to the nearest hazardous obstacles. On the left side of a two-way roads, it is measured from the centerline to the nearest hazardous obstacle. Wider clear zones are needed on the outside curves and where the roadside slopes down away from the edge of the road.4

On curbed roads, utility poles, fire hydrants and other obstructions should be at least 1.5 feet from the face of the curb – greater distances are recommended, since a curb will not stop a car from leaving the road.

| Desired Clear Zone | |

|---|---|

| Road Type | Desired Clear Zone Width |

| Low volume road (ADT * < 400 Vehicles per day) | 6.5 ft. |

| Local road (ADT > 400 vehicles per day) | 7 – 10 ft. |

| Arterials and collectors | See Roadside Design Guide or the Highway Design Manual |

* ADT = Average Daily Traffic

Treatment of Roadside Hazards

When deciding what to do with a hazard that reduces the size and condition of an available clear zone, review the municipality’s accident history to see what types of losses have occurred. The questions on the following checklist will help decide what do with the hazardous condition:

Municipalities have qualified immunity for claims alleging negligent planning or design of roads and highways, including the establishment and maintenance of clear zones, barriers and delineation markings. In New York, municipalities are not liable for reasonable road design decisions unless there was proof that the plan evolved without adequate study or lacked a reasonable basis.5 The choice of one plan over another will not be deemed as proof of negligence unless there is evidence that the municipality made this decision without a reasonable basis.

What is a reasonable study or evaluation? Generally, following engineering standards and practices, and consulting with a professional engineer if there is deviation from those standards is in order. An on-site study is certainly necessary, and budgetary considerations are a factor to be considered when determining what type of action to take. Consider this example. In a lawsuit alleging negligence against a municipality, a plaintiff claimed that a four-way intersection should have been equipped with a traffic control device instead of two stop signs. The municipality offered as its study the high cost of the traffic light as opposed to the stop signs, the relatively few accidents that occurred in the intersection, and the opinion of the mayor that traffic lights would not have been any better that the stop signs. This would not meet the requirement that for an adequate study, because no actual, empirical study of the intersection was conducted, no qualified engineer was involved, and the applicable standards (i.e., Uniform Manual of Traffic Control Devices) were not consulted. The municipality did not prevail.

To obtain copies of Cornell Local Roads Program publications, call (607) 255-8033.

To purchase NYSDOT publications, call Plan Sales at (518) 457-2124.

AASHTO publications can be purchased by calling 800-231-3475 or going to bookstore.transportation.org.

1 National Safety Council: Injury Facts, 2002 Edition.

2 The original source for this is the NYS DMV Form 144A: Summary of Motor Vehicle Accidents-New York Statewide for 2000

3 Source: NCHRP Report 500 Volume 6: A Guide for Addressing Run-Off-Road Collisions

4 Detailed discussion of clear zone width can be found in the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Roadside Design Guide and in the NYS Highway Design Manual. For low volume roads, see the Guidelines for Geometric Design of Very Low Volume Roads, AASHTO, 2001.

5 The case often cited for this theory is Weiss v. Fote, 7 N.Y.2d 579, 200 N.Y.S. 2d 409