Chapter IX. Social Trip Mode

A. Introduction

Understanding the factors that affect mode choice is essential for planning for the transportation needs of future generations. With respect to trip purpose, all work and no play make Jack and Jill dull children. So while policymakers and transportation analysts, perhaps understandably, tend to focus on commuter travel, other trips—including social trips—are important to quality of life as well. Developing social relations independent of familial and neighbor relationships is a central part of the teenage transition into adulthood—and social and recreational travel is central to this transition. Indeed, social and recreational trips form a larger share of teen travel than adult travel. Regardless of age, however, research on subjective well-being has consistently shown that time spent in social and recreational activities is positively associated with happiness (Dolan, Peasgood, and White 2008). Accordingly, this chapter uses data from the NHTS surveys to construct a model of mode choice for social trips.

B. Methodology

As we explained in the previous chapter, the NHTS asks respondents about the purpose of their travel, and we classify their travel as social travel if they give “visiting friends or relatives” or “other social or recreational” as reasons for making a trip. However, using the NHTS to analyze social travel in this manner has limitations. Although the respondents give the purpose of their trips, some purposes—for example, shopping—can be either social or non-social. An after work journey to a grocery store in search of food for dinner by a weary single mother is almost certainly a non-social shopping trip. But if a teenager travels to the mall and spend time with friends, the trip will be designated a “shopping” trip in the NHTS despite the obvious social component. Because our analysis includes only trips described explicitly as social trips, our analysis unavoidably omits some social and recreational trips.

As with the commute mode choice analysis above, multinomial logistic regression is the most common statistical technique used to test the relationships between various factors and mode choice. We use this technique in our analysis of social and recreational travel as well.

In addition to the variables described and used in the analyses above, the models presented here include the additional analysis-specific variables:

- The social trips variable refers to the number of social trips the respondent has taken on the survey day.

- The distance variable refers to the distance traveled for a given trip. Mode choice varies greatly by distance: for example, people become much less likely to choose non-motorized forms of transportation for longer trips; as a result, we use the natural log of distance.

- The weekend variable identifies whether the respondent took the trip on Saturday or Sunday. We include this variable because social trips taken on the weekend may differ in both frequency and type from social trips taken on a weekday.

As in the previous analytical sections, we estimated a quasi-cohort model of mode choice for social trips. For this model, we estimated a Poisson regression model of the share of social trips made by single-occupancy vehicle (SOV), rather than use any other mode of transportation. We chose this modeling form due to computational limitations of estimating a multinomial mode choice model with a very large (three data years, combined) dataset. While the use of the Poisson model may obscure many of the trade-offs made between the various non-SOV modes of transportation, the following model provides insight into the choice to drive alone for social purposes.

C. Descriptive Statistics

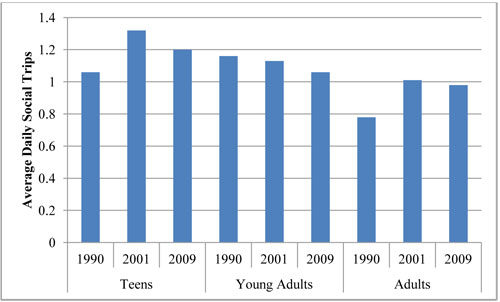

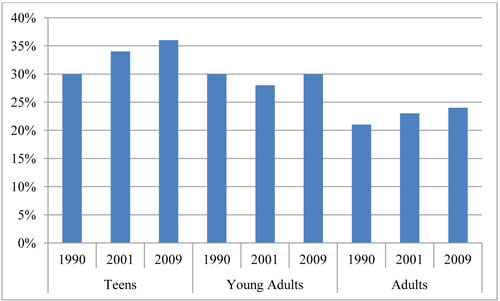

Figure 36 illustrates the average daily social trips taken by different age groups in each survey year.29 Social trip making is relatively consistent across age categories, ranging from 0.8 to 1.3 trips per day. High school students and young adults make the highest number of social trips, and adults make the fewest. The number of social trips declined slightly from 2001 to 2009, as did the number of trips overall. As Figure 37 shows, social trips comprise a higher percentage of tripmaking among both teens and young adults than adults.

Figure 36: Average Daily Social Trips by Age Group (1990, 2001, and 2009)

Figure 37: Percentage of Social Trips by Age Group (1990, 2001, and 2009)

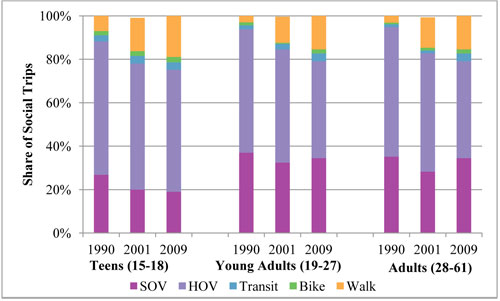

Figure 38 illustrates mode choice for different age groups across the three surveys for social trips. Automobile travel is by far the most common mode for social travel across all age groups and all years. In 2001 and 2009, automobile trips account for 70–80 percent of trips for every age group. However, many of these trips involve multiple passengers, making them high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) trips. Every automobile trip for children age 0–14, for example, is an HOV trip.30 As teenagers obtain drivers’ licenses, however, they quickly begin making single-occupancy vehicle (SOV) trips in place of the HOV trips—roughly 20 percent of their total trips for all three years.

Figure 38: Social Trip Mode by Age Group and Year (1990, 2001, and 2009)

Walking is the next most common mode of social and recreational travel, although it represents less than 20 percent of total trips in 2001 and 2009. Young adults and adults make a smaller percentage of trips by walking than other groups for all three years. Children are the most likely to walk, followed by high school students and elderly people. We see a slight increase in walking from 2001 to 2009 across all age categories.

Public transit and bicycling trips for social and recreational purposes are comparatively rare. Children under 14 make a higher percentage of their trips by bicycle (5–7%) and public transit (1–2%) than other groups. Bicycle use quickly declines as people grow older. However, teenagers make roughly two percent of their trips by bicycle, and that percentage drops to one to two percent for the remaining population. Transit use for social and recreational trips, on the other hand, increases as people grow older—and has also increased slightly from 2001 to 2009 for all age groups—but still accounts for only one to four percent of total trips.

D. Cross-Sectional Model Results

Table 38 to Table 41present results for the social and recreational mode choice models. The tables show results for each travel mode relative to driving alone. In Table 38, which compares the likelihood of carpooling relative to driving alone, one sees a number of expected results. Women—youth and adults—are more likely to carpool, although for adults, similar to the commute mode analysis above, many of those trips are likely chauffeuring trips for children. As other scholars find, immigrant and Hispanic adults are also more likely to carpool; carpooling is also higher in households with a greater number of children, most likely due to “fampool” and chauffeuring trips. Adults with medical conditions are more likely to carpool as well, perhaps as passengers. Both youth and adults are more likely to carpool for longer-distance trips, with an increase in the number of social trips, and on the weekend. However, in a finding that runs counter what we observed with journey-to-work mode choice, the likelihood of carpooling increases with income for adults, but has no apparent effect on youth.

With respect to our variables of interest, young adults who live with their parents are less likely to carpool. Licensing regulations generally do not have a statistically significant effect on the probability of carpooling for youth social and recreational trips. Contrary to expectations, daily web use appears to make people less likely to carpool relative to driving alone.

| Social Mode: Carpool (base: driving alone) | Youth (15-26) 1990 |

Youth (15-26) 2001 |

Youth (15-26) 2009 |

Adults (27-61) 1990 |

Adults (27-61) 2001 |

Adults (27-61) 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.01 | -0.03** |

0.01*** |

-0.01*** |

-0.02*** |

| Female | 0.23*** |

0.35*** |

0.28*** |

0.42*** |

0.45*** |

0.32*** |

| NH White | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted |

| NH Black | 0.31** |

0.57*** |

0 | -0.50*** |

-0.10 | -0.08 |

| NH Asian | no data | -0.13 | 0.83*** |

0 | 0.14 | |

| Hispanic | 0.34** |

-0.17 | 0.13 | 0.36** |

0.44*** |

0.27*** |

| Other | -0.02 | 0.21 | 0.38 | 0.47* | 0.15 | 0.10 |

| Immigrant | no data | 0.31** |

-0.02 | no data | 0.18** |

0.17** |

| Daily web use | no data | -0.14* |

-0.31*** |

no data | -0.05 | -0.09* |

| Medical condition | no data | 0.52* |

0.41 | no data | 0.50*** |

0.41*** |

| Young Adult Lives w/Parents | -0.66*** |

-0.36*** |

-0.39*** |

omitted | omitted | omitted |

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Household Income (ln) | -0.16*** |

-0.16*** |

-0.31*** |

0.15*** |

0.16*** |

-0.01 |

| Number of Children | 0.36*** |

0.37*** |

0.18*** |

0.37*** |

0.34*** |

0.22*** |

| Trip Characteristics | ||||||

| Trip Distance (ln) | 0.13*** |

0.10*** |

0.07* |

0.18*** |

0.18*** |

0.17*** |

| # of social trips that day | 0.04* |

0.05*** |

0.06*** |

0.04** |

0.04*** |

0.14*** |

| Weekend | 0.32*** |

0.58*** |

0.47*** |

0.40*** |

0.75*** |

0.70*** |

| Geographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Population Density (ln) | 0 | 0.10*** |

0.06** |

-0.05** |

-0.01 | -0.01 |

| New York Area | 0.51*** |

0.12 | -0.26 | -0.17 | 0.13* |

0.26*** |

| MSA > 3 million | -0.34*** |

0.04 | 0.14 | 0.01 | -0.10** |

-0.05 |

| State Licensing Regulations | ||||||

| Stringency: Lowest | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | ||

| Stringency: Low | -0.20* |

0 | omitted | 0.11 | -0.04 | omitted |

| Stringency: Medium | no data | -0.12 | 0.04 | no data | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Stringency: High | no data | 0.15 | -0.05 | no data | -0.02 | -0.06 |

| Constant | 1.04* |

0.98* |

1.13** |

-2.57*** |

-2.20*** |

-0.33* |

| N | 4,685 | 11,281 | 14,970 | 8,981 | 54,257 | 101,997 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| KEY: |

|---|

| Statistically Significant |

| Statistically Significant Over Time (across all the years for which data were available) |

Table 39 illustrates the likelihood of using transit relative to driving alone. Many of the variables are relatively consistent across both age groups. African Americans tend to be more likely to use transit than non-Hispanic Whites. With one exception (youth in 1990), income is negatively related to transit use; those with higher incomes are less likely to use transit. Individuals are more likely to use transit in denser areas and in transit-rich New York City. The probability of taking transit increases with distance for youth in all three survey years and for adults in 2001 and 2009. With one exception (youth in 2009), traveling on the weekend does not appear to have an effect on transit use for youth or for adults.

There are a few differences between youth and adults. Age seems to make a difference even within the youth age group. As youth age from their teens to their 20s, they are less likely to use transit for social trips. Age is not significant among adults. Also, young adults who live with their parents are less likely to use transit for social trips. Youth who take a greater number of social trips in a given day are less likely to use transit, a finding that likely reflects the difficulty of coordinating multiple transit trips.

In addition, stringent licensing laws have a statistically significant effect in nearly every case for youth, but the direction of the effect varies. The laws also have a statistically significant effect on adult travel; as we mention in the chapter on commute mode, we hypothesize that the licensing variable may also reflect other characteristics of states that adopt stricter licensing regulations.

| Social Mode: Transit (base: driving alone) | Youth (15-26) 1990 |

Youth (15-26) 2001 |

Youth (15-26) 2009 |

Adults (27-61) 1990 |

Adults (27-61) 2001 |

Adults (27-61) 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||

| Age | -0.13*** |

-0.11*** |

-0.17*** |

-0.03* |

0 | -0.01 |

| Female | -0.25 | -0.1 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.43** |

0.25 |

| NH White | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted |

| NH Black | 1.52*** |

1.70*** |

1.09*** |

0.53 | 0.45** |

0.48** |

| NH Asian | no data | 1.16** | 0.15 | no data | 1.15*** |

0.4 |

| Hispanic | 0.73* |

-0.2 | -0.3 | 1.32*** |

0.44 | -0.12 |

| Other | 0.76 | 0.24 | -0.38 | 0.09 | 0.58* |

-1.19*** |

| Immigrant | no data | -0.94** |

-0.02 | no data | 0.29 | -0.31 |

| Daily web use | no data | 0.56* |

0.13 | no data | -0.06 | -0.14 |

| Medical condition | no data | 2.58*** |

0.51 | no data | -0.09 |

1.13*** |

| Young Adult Lives w/Parents | -0.95*** |

-0.59* |

-0.37 | omitted | omitted | omitted |

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Household Income (ln) | -0.19 | -0.25** |

-0.92*** |

-0.53*** |

-0.71*** |

-0.90*** |

| Number of Children | 0.36*** |

0.36** |

0.20** |

0.04 | 0.06 | 0.19** |

| Trip Characteristics | ||||||

| Trip Distance (ln) | 0.26* |

0.32*** |

0.40*** |

0.03 | 0.33*** |

0.27*** |

| # of social trips that day | -0.32*** |

-0.21*** |

-0.07* |

-0.16* |

0.04 | 0.07*** |

| Weekend | -0.33 | -0.16 | 0.59*** |

-0.03 | 0.06 | -0.06 |

| Geographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Population Density | 0.52*** |

0.55*** |

0.72*** |

0.69*** |

0.69*** |

0.88*** |

| New York Area | 1.39*** |

1.89*** |

0.97** |

0.21 | 1.21*** |

0.50** |

| MSA > 3 million | -0.34 | -0.05 | 1.16*** |

0.47 | 0.93*** |

0.17 |

| State Licensing Regulations | ||||||

| Stringency: Lowest | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | ||

| Stringency: Low | 1.06*** |

0.7 | omitted | 1.48*** |

1.46*** |

omitted |

| Stringency: Medium | no data | 0.97** |

-1.58** |

no data | 1.68*** |

-1.80*** |

| Stringency: High | no data | 0.72 | -1.14** |

no data | 0.24 | -0.89 |

| Constant | 0.64 | -0.27 | 1.97* |

1.22 | -0.16 | -1.90*** |

| N | 4,685 | 11,281 | 14,970 | 8,981 | 54,257 | 101,997 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| KEY: |

|---|

| Statistically Significant |

| Statistically Significant Over Time (across all the years for which data were available) |

Table 40 illustrates the likelihood of bicycling relative to driving alone. Fewer statistically significant findings emerge from this model, probably because the data contain relatively few bicycling trips for analysis. A few expected results appear, however. People are less likely to bicycle as trip distance increases. Women are also less likely to bicycle than men; and African Americans tend to be less likely to travel by bicycle than non-Hispanic whites. Income is not related to the likelihood of biking among youth but has a negative relationship to bicycling among adults in two of years. Being a young adult living at home and daily web use are not statistically significant. State licensing regulations are positively related to travel by bicycle for adults, and—in 1990 and 2009—are not related to bicycle travel.

| Social Mode: Bike (base: driving alone) | Youth (15-26) 1990 |

Youth (15-26) 2001 |

Youth (15-26) 2009 |

Adults (27-61) 1990 |

Adults (27-61) 2001 |

Adults (27-61) 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||

| Age | -0.02 | -0.13** |

-0.06 | -0.03** |

-0.02*** |

0.01* |

| Female | -0.03 | -0.48 | -1.16*** |

-0.4 | -0.61*** |

-1.04*** |

| NH White | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted |

| NH Black | -0.67 | 1.1 | -1.54*** |

-3.59*** |

-1.56*** |

0.13 |

| NH Asian | no data | -3.03*** |

0.18 | no data | -1.04* | -0.27 |

| Hispanic | -24.57*** |

0.41 | -0.01 | -0.26 | -1.43*** |

-0.06 |

| Other | 1.07* |

1.25** |

-0.51 | -20.99*** |

-1.25** |

0.14 |

| Immigrant | no data | -0.35 | 0.35 | no data | 0.47* |

0.17 |

| Daily web use | no data | -0.14 | 0.13 | no data | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| Medical condition | no data | 1.44 | 0.56 | no data | -0.02 | -0.56** |

| Young Adult Lives w/Parents | -0.46 | -1.05** |

0.36 | omitted | omitted | omitted |

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Household Income (ln) | -0.01 | -0.19 | -0.22 | -0.34* |

-0.18* |

-0.17 |

| Number of Children | 0.42*** |

0.17 | 0.09 | 0.35*** |

0.18*** |

0.11* |

| Trip Characteristics | ||||||

| Trip Distance (ln) | -0.38*** |

-0.58*** |

-0.54*** |

-0.43*** |

-0.45*** |

-0.44*** |

| # of social trips that day | -0.01 | -0.1 | 0.06** |

0 | 0.16*** |

0.07*** |

| Weekend | -0.56* |

-0.15 | -0.39 | 0.27 | 0.30** |

-0.05 |

| Geographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Population density | 0.21 | 0 | 0.08 | -0.13 | -0.05 | 0.02 |

| New York | 0.52 | 0.45 | -1.82** |

-2.37*** |

0.50* |

-0.90*** |

| MSA > 3 million | -0.01 | 0.57 | 0.25 | -0.17 | -0.04 | -0.17 |

| State Licensing Regulations | ||||||

| Stringency: Lowest | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | ||

| Stringency: Low | 0.13 | 0.93* |

omitted | 0.02 | 0.35 | omitted |

| Stringency: Medium | no data | 0.68 | -0.48 | no data | 0.49** |

0.61** |

| Stringency: High | no data | 1.29** |

-0.3 | no data | 1.21*** |

0.63** |

| Constant | -2.27 | 0.97 | -0.68 | 1.75 | -0.66 | -3.34*** |

| N | 4,685 | 11,281 | 14,970 | 8,981 | 54,257 | 101,997 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| KEY: |

|---|

| Statistically Significant |

| Statistically Significant Over Time (across all the years for which data were available) |

Finally, Table 41illustrates the likelihood of walking relative to driving alone. As expected, people are less likely to walk as their incomes and trip distances increases. They are, however, more likely to walk in dense urban environments. Immigrants and people living in the New York are more likely to walk for social and recreational purposes than are others. People with a medical condition are also more likely to walk, which contradicts research showing that the disabled are more likely to drive because it requires less physical exertion than walking. Finally, the driver’s licensing results are mixed, suggesting once again that this state variable reflects some other characteristic of states that adopt these tough regulations.

| Social Mode: Walk (base: driving alone) | Youth (15-26) 1990 |

Youth (15-26) 2001 |

Youth (15-26) 2009 |

Adults (27-61) 1990 |

Adults (27-61) 2001 |

Adults (27-61) 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||

| Age | -0.11*** |

0.02 | -0.02 | 0 | 0 | -0.01* |

| Female | -0.46** |

0.03 | -0.03 | 0.46*** |

0.55*** |

0.13** |

| NH White | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted |

| NH Black | 0.16 | 0.74*** |

0.51* |

0.23 | -0.16 | -0.1 |

| NH Asian | no data | 0.47 | 1.29*** |

no data | 0.1 | -0.1 |

| Hispanic | -0.09 | -0.62** |

0.45*** |

-0.03 | -0.27* |

0.04 |

| Other | 0.84* |

0.44 | 0.35 | 0.78* |

0.01 | -0.07 |

| Immigrant | no data | -0.09 | 0.51** |

no data | 0.45*** |

0.40*** |

| Daily web use | no data | -0.07 | -0.2 | no data | 0.21*** |

0.06 |

| Medical condition | no data | 1.58*** |

1.68*** |

no data | 0.43*** |

-0.1 |

| Young Adult Lives w/Parents | -0.83*** |

-0.26 | -0.35** |

omitted | omitted | omitted |

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Household Income (ln) | -0.53*** |

-0.27*** |

-0.33*** |

0.11 | 0.18*** |

-0.13** |

| Number of Children | 0.30*** |

0.30*** |

0.19** |

-0.11 | 0 | -0.01 |

| Trip Characteristics | ||||||

| Trip Distance (ln) | -1.72*** |

-1.46*** |

-1.50*** |

-1.48*** |

-1.30*** |

-1.42*** |

| # of social trips that day | 0.05 | -0.02 | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.07*** |

| Weekend | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.08 | -0.1 | -0.01 | 0.03 |

| Geographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Population density | 0.18** |

0.35*** |

0.06 | 0.01 | 0.09*** |

0.06*** |

| New York | -0.12 | 0.86*** |

0.53** |

0.63*** |

0.63*** |

0.64*** |

| MSA > 3 million | 0.07 | -0.05 | 0.27* |

0.19 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| State Licensing Regulations | ||||||

| Stringency: Lowest | omitted | omitted | omitted | omitted | ||

| Stringency: Low | 0.51** |

0.31 | omitted | 0.32* |

0.04 | omitted |

| Stringency: Medium | no data | 0.58*** |

-0.86** |

no data | 0.19** |

0.32* |

| Stringency: High | no data | 0.44* |

-0.71* |

no data | 0.12 | 0.39** |

| Constant | 6.53*** |

0.81 | 1.43** |

-2.63** |

-2.69*** |

-0.33 |

| N | 4,703 | 13,311 | 17,817 | 9,007 | 55,815 | 111,112 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| KEY: |

|---|

| Statistically Significant |

| Statistically Significant Over Time (across all the years for which data were available) |

E. Quasi-Cohort Model and Model Results

As in the previous analytical chapters, we estimated a quasi-cohort model of mode choice for social trips. For this model, we estimated a Poisson regression model of the share of social trips made by single-occupancy vehicle (SOV), rather than by any other mode of transportation. We chose this modeling form due to the computational challenges of estimating a multinomial logistic regression mode choice model with a very large (a combined three years of national data) dataset. While the use of the Poisson model may obscure some of the trade-offs made among the various non-SOV modes of transportation, the following model provides insight into the choice to drive alone for social purposes.

Table 42 presents the results of the social trip quasi-cohort model. The coefficients on the control variables carry their expected signs and broadly conform to the findings from our cross-sectional analyses. The model suggests, for instance, that women are less likely to drive alone to social events than men, and all non-white racial and ethnic groups are less likely to drive alone to social destinations than are whites. Education and greater access to automobiles are all positively associated with driving alone for social purposes, all else equal. However, after controlling for education and auto access, income is negatively associated with driving alone for social purposes. This finding echoes the findings in the cross-sectional models that higher-income individuals are more likely to carpool for social trips. The model also suggests that those living in denser areas (as well as those surveyed on the weekend) are less likely to drive alone.

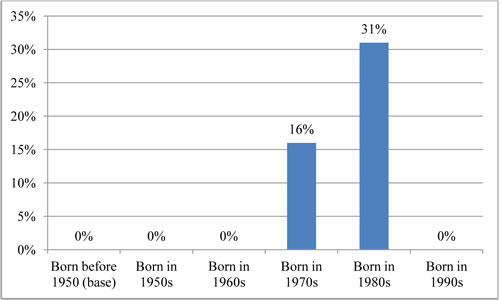

Turning to the variables of interest, the model suggests that daily internet users are more likely to drive alone for social purposes than are those who do not use the internet daily, all else equal. Similarly, youth who live with their parents are far more likely to drive alone for social trips than are youths who live elsewhere. And while those in 2001 and 2009 appear to make fewer solo-driving social trips than did those in 1990, the model suggests that later birth cohorts (1970s and 1980s) tend to make more of their trips by single-occupancy vehicle than do those who were born in earlier decades (see Figure 39). For those born in the 1990s, we find no conclusive evidence of a cohort effect.

| Coefficient | Sig. | t-Statistic | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||

| Female | -0.107 | *** | -10.51 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | 0.075 | *** | 12.86 | <0.001 | ||

| Age Squared | -0.001 | *** | -11.34 | <0.001 | ||

| Race / Ethnicity (omitted category: Non-Hispanic White) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | -0.023 | -1.02 | 0.306 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Asian (2009 Only) | -0.055 | -1.62 | 0.104 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Other | -0.092 | *** | -2.66 | 0.008 | ||

| Hispanic | -0.085 | *** | -3.82 | <0.001 | ||

| Education (omitted category: No HS Diploma) | ||||||

| For Youth: Highest Degree Achieved in Household | ||||||

| High School Diploma | 0.323 | *** | 4.97 | <0.001 | ||

| Some College | 0.407 | *** | 6.94 | <0.001 | ||

| Bachelor's Degree | 0.394 | *** | 6.63 | <0.001 | ||

| Graduate Degree | 0.396 | *** | 6.31 | <0.001 | ||

| For Adults: Highest Degree Personally Achieved | ||||||

| High School Diploma | 0.074 | 1.59 | 0.113 | |||

| Some College | 0.106 | ** | 2.31 | 0.021 | ||

| Bachelor's Degree | 0.115 | ** | 2.48 | 0.013 | ||

| Graduate Degree | 0.112 | ** | 2.38 | 0.017 | ||

| Reports Working | 0.245 | *** | 18.52 | <0.001 | ||

| Uses Web Daily | 0.051 | *** | 4.19 | <0.001 | ||

| Reports Driving | 4.548 | *** | 30.54 | <0.001 | ||

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Income (ln) | -0.017 | ** | -2.29 | 0.022 | ||

| Number of Adults in HH | -0.044 | *** | -5.88 | <0.001 | ||

| Number of Children in HH | -0.293 | *** | -49.17 | <0.001 | ||

| Youth, Lives with Parents | 0.395 | *** | 12.84 | <0.001 | ||

| Ratio of Cars to Adults in HH | 0.136 | *** | 13.41 | <0.001 | ||

| Trip Characteristic | ||||||

| Trip Was on Weekend | -0.436 | *** | -32.68 | <0.001 | ||

| Geographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Population Density (ln) | -0.009 | *** | -2.60 | 0.009 | ||

| In MSA with > 3M Population | 0.005 | 0.46 | 0.648 | |||

| Year | ||||||

| Year: 2001 (base: 1990) | -0.219 | *** | -8.23 | <0.001 | ||

| Year: 2009 (base: 1990) | -0.299 | *** | -8.42 | <0.001 | ||

| Cohorts (base: Born before 1950) | ||||||

| Born in 1950s | 0.009 | 0.40 | 0.692 | |||

| Born in 1960s | 0.022 | 0.61 | 0.539 | |||

| Born in 1970s | 0.151 | *** | 2.98 | 0.003 | ||

| Born in 1980s | 0.269 | *** | 3.94 | <0.001 | ||

| Born in 1990s | 0.107 | 1.26 | 0.208 | |||

| Constant | -6.912 | *** | -31.78 | <0.001 | ||

| N | 123,167 | |||||

| R-Square | 0.154 | |||||

| Statistically Significant | ||||||

Figure 39: Expected Percentage Change in Share of Social Trips Made by SOV by Cohort

F. Conclusion: Social Trip Mode

Social travel has received relatively little attention from researchers compared with other types of travel—in particular, the commute to work. While the previous analyses show that the recession has had a large effect on the travel behavior of teens and young adults, our analysis presented in Chapter IX finds that the effects of the economic downturn on social travel are less clear. The total number of social trips declined slightly from 2001 to 2009, but the share of social trips relative to other types of trips actually increased slightly. This finding contradicts expectations that people are most likely to reduce discretionary travel in worsening economic circumstances.

| Youth (15–26) 1990 |

Youth (15–26) 2001 |

Youth (15–26) 2009 |

Adults (27–61) 1990 |

Adults (27–61) 2001 |

Adults (27–61) 2009 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carpool (Base: driving alone) | ||||||

| Employment Status | (Not included in the model) | (Not included in the model) | ||||

| Young Adult Living at Home | - |

- |

- |

(Not included) | ||

| Technology (Web Use) | n/a | - |

- |

n/a | 0 |

- |

| License Stringency | 0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Transit (Base: driving alone) | ||||||

| Employment Status | (Not included in the model) | (Not included in the model) | ||||

| Young Adult Living at Home | - |

- |

0 |

(Not included) | ||

| Technology (Web Use) | n/a | + |

0 |

n/a | 0 |

0 |

| License Stringency | - |

? |

- |

+ |

? | ? |

Bicycling (Base: driving alone) | ||||||

| Employment Status | (Not included in the model) | (Not included in the model) | ||||

| Young Adult Living at Home | 0 |

- |

0 |

(Not included) | ||

| Technology (Web Use) | n/a | 0 |

0 |

n/a | 0 |

0 |

| License Stringency | 0 |

+ |

0 |

0 |

+ |

+ |

Walking (Base: driving alone) | ||||||

| Employment Status | (Not included in the model) | (Not included in the model) | ||||

| Young Adult Living at Home | - |

0 |

- |

(Not included) | ||

| Technology (Web Use) | n/a | 0 |

0 |

n/a | + |

0 |

| License Stringency | + |

+ |

- |

+ |

? | + |

While the recession may have had unexpected effects on the amount of social travel, it has more expected effects on mode choice. As seen in the previous chapter on commute mode choice, household income strongly affects commuter mode choice, increasing the likelihood of driving alone, and we observe similar results for social trip mode choice. For youth, income has a negative effect on carpooling, transit use, and walking; for adults, income has a negative effect on transit use and bicycling. However, the models suggest that higher-income adults are more likely to carpool than drive alone for social trips, an unexpected—but highly social—result.

On the other hand, trip characteristics frequently had statistically significant effects on mode choice. For example, trip distance, the number of social trips taken in the survey day, and weekend travel all had positive effects on carpooling for both youth and adults. Conversely, trip distance had a negative effect on bicycling and walking for both groups. Geographic characteristics had less of an effect overall, but population density and living in New York both had positive effects on transit use.

As for other variables of interest, daily Internet use had almost no effect for youth and adults, and licensing had either no effect or inconsistent effects. Young adults living at home were more likely to drive alone in most of the models, including the carpooling models. This finding perhaps reflects their desire to maintain a measure of independence while living with their parents.

Our analysis further revealed some differences in social travel between youth and adults. As noted previously, studies have shown that being Hispanic or an immigrant increases the likelihood of carpooling or walking over driving alone. As with our commuting analysis, the social trips analysis shows that this trend remains consistent over time for adults, but not for youth. In other words, the relationship between socio-demographic categories and mode choice for recreational travel may be weakening as well.

Finally, the quasi-cohort model finds that being born in the 1970s and especially the 1980s is associated with more driving alone (perhaps to bowl alone) to social destinations, while being born in earlier decades or in the 1990s has no effect on driving alone on social trips. While the 1990s results compares only the social travel mode choice of 15 to 19 year olds with similar age cohorts born in the 1980s and 1970s, this finding does suggest that rates of driving alone, after controlling for a wide array of other factors, is down among the latest generation of teens.

30The NHTS surveys report that children make a very small number of their social trips—less than a tenth of a percent—in single-occupancy vehicles, but we can safely assume that number is due to survey error.