U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

|

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-06-095

Date: May 2006 |

Traffic congestion is increasing significantly throughout the United States. Congestion is increasing in rural areas and urban areas, in small cities, and large cities. Further, the transportation community realizes there is no one proven way to fix the congestion problem and that a comprehensive approach of multiple congestion-reducing strategies is needed. One of these strategies is to operate the existing roadway system more efficiently or, in other words, to get more out of what already exists.

|

The purpose of this document is to provide direction, guidance, and recommendations on how to proactively and comprehensively coordinate freeway and arterial street operations. |

Proactively managing and operating existing freeways and adjacent arterials in a comprehensive manner, from a transportation system user's perspective, are major steps toward operating all modes of the transportation system at maximum efficiency. However, this handbook is not just about using system management strategies to operate freeways and arterials more efficiently; rather, the focus of this guide is on operating freeways and adjacent arterials together in a coordinated manner that treats these roadways not as separate entities, but as an interconnected traffic operations corridor. This is how transportation users view and use these roadways. Users will often, for example, divert from a freeway to an adjacent arterial during a freeway incident because they realize the adjacent arterial will get them to their destination more efficiently in this scenario.

The purpose of this handbook is to provide direction, guidance, and recommendations for transportation managers, engineers, technicians, and planners on how to proactively and comprehensively coordinate freeway and arterial street operations. There are many guidance documents on how to manage and operate transportation facilities individually, but this document is a first-of-a-kind because it focuses on how to coordinate the operations of different facility types that are typically operated by separate organizational entities with separate missions. To support the goal and purpose of this document, specific objectives include:

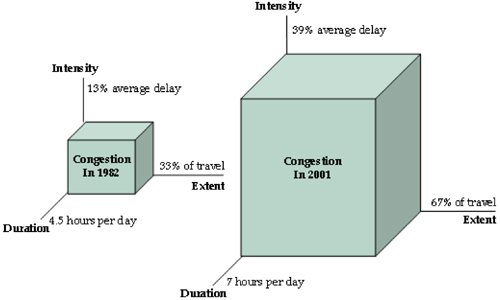

Demand for highway travel by Americans continues to grow as the population increases, particularly in metropolitan areas. The effects of congestion are captured in a number of measures and perceptions, including visible and consistent roadway congestion, the loss of personal and professional time, environmental degradation, and general traveler frustration—in essence, a reduction in overall mobility and accessibility. Figure 1 illustrates how congestion has grown in numerous ways to affect more people at a greater rate for longer periods of time.

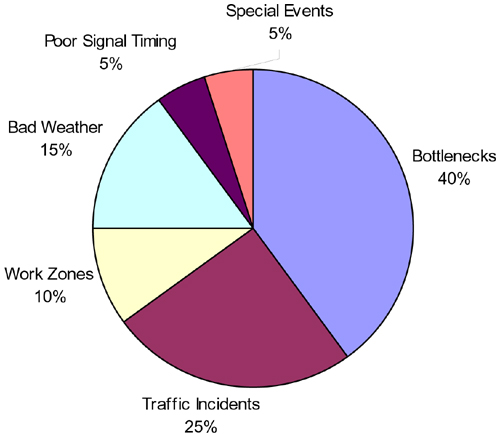

While traffic congestion can be easily seen and measured, the underlying causes of traffic congestion are more difficult to discern. Recent research has determined these "root" causes on a national scale, as shown in figure 2. These percentages shown are national averages, so the percentages for an individual metropolitan area may vary depending on the local conditions.

Delays (resulting from congestion) at particular locations in a transportation network are certainly aggravating to those using the system; but these delays are part of a much larger picture of how a transportation system allows people and goods to move around a metropolitan area. The consequences of congestion are much more serious to a community. For example:(1)

Figure 1. Chart. Increase in congestion in the past 20 years in the largest U.S. cities.(2)

Figure 2. Chart. Sources of traffic congestion.(3)

The surface transportation system has been operated historically by separate entities with specific missions, goals, and objectives. These entities may have varying authority that may be either very limited or rather broad. In addition, responsibilities may overlap. Typically, the State government manages and operates freeway facilities and most major arterials and city or county governments manage and operate secondary arterials, collectors, and local streets. Furthermore, some functions, such as policing or emergency services, typically do not correspond with the agency that operates the roadway facilities. The result of this complex institutional arrangement is that the transportation system is operated from a single agency or facility-specific perspective, resulting in less than optimal operations when viewed from a systemwide perspective. It is this suboptimal systemwide perspective that motorists experience.

This challenge of operating freeways and adjacent arterial streets from a coordinated, system perspective was identified long ago. Many agencies have discussed ways to better coordinate their freeways and arterials, but few have actually implemented a comprehensive method for doing so. The reasons for this lack of communication and interoperability range from institutional barriers to technical challenges. Recent advancements in technology (i.e., centralized software systems, high-speed telecommunications, and interoperable ITS devices through common standards), coupled with improvements in institutional coordination (i.e., many regions now have multi-agency, regional-level ITS and traffic operations working groups), are now providing regions with the tools and abilities to create proactive plans and procedures for operating freeways and arterial streets in a coordinated manner. While it is a challenge, regions may significantly benefit by taking advantage of these advancements in technology and institutional collaborations by operating their freeways and arterial streets in a coordinated manner.

Coordinated freeways and arterials (CFA) operations is the implementation of policies, strategies, plans, procedures, and technologies that enable traffic on freeway and adjacent arterials to be managed jointly as a single corridor and not as individual, separate facilities. These policies, strategies, etc. should have an end goal of improving the mobility, safety,

|

CFA operations are the implementation of policies, strategies, and so forth that manages traffic on freeways and adjacent arterials jointly as a single corridor and not as individual facilities. |

and environment of the overall corridor and not just individual facilities. For the purposes of this handbook, a corridor is defined as a freeway facility together with adjacent and connecting arterial streets that collectively function to move vehicles through a geographic area. While the term "corridor" could be applied to other facilities and modes of transportation, this handbook is designed to focus specifically on freeways and arterial streets. The concepts presented in this handbook could apply to corridors in urban, suburban, or rural areas.

The operation of freeways and adjacent arterial streets is often closely linked and at visible example of how taking a single agency perspective can result in suboptimal, system-level performance. While agencies may not manage them as such, motorists view freeways and adjacent arterials as an interconnected corridor with multiple routes to travel from their origin to destination.

This point can perhaps be best illustrated with an example of a major incident occurring on a State freeway traversing a city. During a major incident, motorists will often attempt to divert around the incident via the adjacent city street system. Often, the routes chosen by motorists are not the quickest, most efficient alternatives. This "relief valve" effect can easily overwhelm the capacity of the local arterials, especially if the city traffic engineer has no advance warning of the impending wave of motorists on the local streets. If the city traffic engineer had known about the incident when it occurred and had pre-arranged signal timing plans to respond to the incident, the impact of the diversion could have been mitigated to some degree. In another freeway incident

|

Agencies that shift from an agency perspective to a system perspective optimize not only the overall system but likely their own roadways as well. |

scenario, motorists may not respond to suggestions to divert off of the freeway if they do not know the local street system and are unaware of good alternate routes. In this case, the freeway is entirely overwhelmed while the adjacent arterial streets operate at normal conditions, which could be under capacity. As a result, this untapped arterial reserve capacity remains unknown to frustrated motorists stuck on the freeway.

These are classic scenarios that occur every day across the nation and highlight the need for CFA operations. It is clear these situations represent major delays and inefficiencies to motorists, who only look at a system perspective. Agencies that shift from an agency perspective to a system perspective not only optimize the entire system, but, in the process, optimize their own roadways as well.

The previous sections documented the need and challenges of coordinating freeway and arterial operations; however, "coordinated operations" is easier said than done, and it involves thinking differently than the past. Many regions, particularly larger regions, have developed a mature system of ITS devices and technologies. Ramp metering systems, incident management systems, Transportation Management Centers (TMC), road weather information systems (RWIS), dynamic message signs (DMS), detector and video surveillance systems, and traveler information systems all represent excellent technologies that help agencies operate their systems more efficiently. However, all too often these systems, while operated more efficiently than in the past, are still operated separately. They are not coordinated across jurisdictional boundaries.

Having a coordinated operations mindset involves utilizing operations-enabling technologies and procedures in a seamless, comprehensive manner from a user's standpoint. Table 1 illustrates the thinking associated with a coordinated operations mindset, as opposed to the traditional mindset.

| Thinking... |

Instead of... |

|---|---|

Coordinated |

Isolated |

System |

Jurisdiction |

Customer focus |

Project focus |

Regional |

Local |

Proactive |

Reactive |

Comprehensive |

Piecemeal |

Real-time information |

Historical information |

24/7 operations |

8/5 operations |

Performance-based |

Output-oriented |

Source: Adapted from http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/aboutus/opstory.htm.(3) | |

Institutional issues are at the core of having a coordinated operations mindset. All of the attributes of a coordinated operations program—policies, plans, procedures, agreements, funding mechanisms, strategies, systems and technologies, operational activities, and so on—take place within the institutional framework. This institutional foundation for transportation systems is multi-agency, multifunctional, and multimodal. Moreover, the authority for transportation decisionmaking is dispersed among several levels, or "tiers," of government (e.g., national, statewide, regional, agency, and individual systems), and often among several agencies or departments within each governmental level. This institutional disconnect can lead to a fragmented delivery system for transportation services, resulting in an agency-specific and/or a mode-specific focus rather than an areawide focus that considers the interaction and operation of the entire corridor. Gaining consensus across a region on having a coordinated operations mindset will help overcome these institutional challenges.

In the broadest sense, coordinated operations would be beneficial on any corridor that experiences congestion, either recurring or nonrecurring. More specifically, there are a number of opportunities for coordination of specific corridors. The opportunities relate back to the sources of congestion shown in figure 2. The sources of congestion lend themselves to four categories of potential CFA congestion mitigation:

Each of these categories presents congestion-causing challenges that would benefit by coordinating operations on a corridor. Combining corridor management strategies with traditional traffic engineering and management approaches will optimize the corridor safety and throughput.

A corridor may have a work zone only once every 10 years, but the impact of closing multiple lanes or entire roadways with major detours for days at a time can have a large impact on the corridor. On the other hand, recurrent congestion occurs very frequently (i.e., every weekday peak period), but the impact is typically less than that of a work zone because most motorists are aware of the bottlenecks and can make a plan to account for this congestion (i.e., leave work earlier or take an alternate route).

Ideally, determining which corridors are candidates for these opportunities for coordination should be made by a consensus of all stakeholders in the region. In the case of work zones and special events, these events are known in advance and should be identified early enough to adequately plan and implement plans and procedures to support corridor operations. Specific guidance on how to develop corridor implementation plans and procedures to mitigate these sources of congestion are provided in chapter 4.

Many studies have documented the benefits of transportation systems operations. For example, freeway management systems, such as ramp metering and incident management, have been shown to reduce traveltimes 20 to 48 percent, increase travel speeds 16 to 62 percent, and decrease accident rates 15 to 50 percent. Meanwhile, arterial management systems, such as advanced traffic signal systems, have been shown to reduce traveltimes 8 to 15 percent, increase travel speeds 14 to 22 percent, and decrease emissions 4 to 13 percent.(4)

However, these benefits are typically for operating freeway and arterial systems independently and not in a coordinated manner. Unfortunately, there have been few empirical studies to show the benefits of coordinated operations above and beyond isolated operations. Table 2 shows the results of a few selected studies that have documented the benefits of coordinating freeway and arterial operations.

As shown in table 2, an empirical study in Scotland showed that coordinating arterial signal timing plans, ramp metering plans, and DMS messages during heavy congestion reduced corridor traveltime by 13 percent. Three simulation-based studies demonstrated similar results.

| Location (Date) |

Background |

Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| M-8 Corridor, Glasgow, Scotland (1997-1998)(5) |

Field deployment of adaptive signal control, ramp metering, and DMS messages to balance traffic loads through corridor. |

Traffic volume: no change. Traveltime: 13% decrease. |

| Anaheim, CA (2000)(6) |

Simulated deployment of alternative corridor operations plans (signal timing plans, ramp metering plans, DMS messages, route diversion plans) during nonrecurring congestion. |

Traveltime: 2-30% decrease. Stop time: 15-56% decrease. |

| San Antonio, TX (2000)(7) |

Simulated deployment of corridor operations plans for integrating incident management, DMS messages, and signal timing plans. |

Freeway management only: 16.2% delay reduction. Integrated freeway and arterial management: 19.9% delay reduction. |

| Seattle, WA (2000)(8) |

Simulated deployment of integrating arterial and freeway advanced traveler information systems (ATIS) in north I-5 corridor. |

Freeway only ATIS: 1.5% delay reduction. Freeway plus arterial ATIS: 3.4% delay reduction. |

The Anaheim study tested a comprehensive, coordinated set of corridor operations plans and found significant traveltime savings up to 30 percent. The San Antonio study found a more modest impact of coordinating freeway and arterial operations: a 16.2 percent delay reduction with just freeway incident management was increased to 19.9 percent when incorporating arterial management and incident management plans.

The benefits of coordinated operations may sometimes be difficult to assess quantitatively, yet in a corridor where tens of thousands of people commute, a modest decrease in traveltime may translate into many quantitative benefits in such areas as:

To a large extent, collisions that occur as a result of stop-and-go-traffic can be reduced if congestion within a transportation corridor is effectively mitigated or the efficiency of corridor management is improved. On a corridorwide basis, these systemic improvements translate into increased safety for drivers.

|

Perhaps the biggest benefit of coordinated operations is the improved communication and coordination between agencies, from which the benefits of working together can far exceed those of just corridor operations. |

Although less obvious, there is a known, direct correlation between improved traffic operations and environmental improvements. First, and perhaps most importantly, is the reduction in the amount of emissions released into the atmosphere. As average vehicle speeds increase towards the posted speed limit, the amount of vehicle pollutants released into the atmosphere generally decreases and vehicles operate at a more fuel-efficient mode due to a reduction in the stop-and-go behavior associated with congestion.

Coordinated operations of freeway and arterial traffic can result in less easily defined qualitative benefits as well. Improved traffic flow, decreased traveltimes, and improved safety all work together to ease motorists' frustration and concerns, casting users' perception of regional transportation officials and agencies in a more positive light. This in turn makes it easier to acquire the needed funding to develop, implement, operate, and maintain transportation systems within the corridor.

Perhaps one of the most valuable benefits, however, is that by developing or improving lines of communication and coordination between agencies, organizations, and the public, the foundation is laid for improved overall understanding of the goals and objectives of each participant in a regional coordination effort. This improved understanding is, potentially, the basis for reaching long-term, corridorwide or regional transportation goals.

This document consists of 6 chapters. Table 3 gives a short description of each chapter in the document.

| Chapter |

Title |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Introduction |

This chapter describes the purpose and objectives of the document and subject area, the definition and need for coordinated operations, and how to use this document. |

| 2 |

Planning for Coordinated Traffic Operations on Freeways and Arterials |

This chapter provides a broad view of the planning-level activities recommended for the successful development of CFA operations examined at a regional level and a corridor-specific level. |

| 3 |

A Framework for Coordinated Operations on a Corridor |

This chapter details the recommended 11-step framework for the entire life cycle of coordinated operations for a specific corridor. |

| 4 |

Applying CFA Operations to Four Opportunity Areas |

This chapter demonstrates how the corridor-level framework can be applied to incident management, work zones, special events, and daily recurring operations. |

| 5 |

Supporting Technologies and ITS Elements |

This chapter presents concepts and technologies that will enhance the efficiency of coordinated freeway and arterial operations. |

| 6 |

Examples of CFA Operations |

This chapter presents practical applications of the CFA process and demonstrates the potential of ITS technology to enhance corridor operations. |

The intended audience of this document is the team of individuals that is involved in or responsible for the planning, coordination, management, or operation of traffic on freeway and arterial facilities (e.g., managers, supervisors, engineers, planners, or technicians that are involved with legislation, policy, program funding, planning, design, project implementation, operations, or maintenance).

This handbook is intended to be an introductory manual to assist practitioners that may be involved in or responsible for the advanced planning and management of travel on freeway and arterial roadways for different congestion-causing scenarios. It is not intended to serve as a detailed technical reference or design guide that addresses all of the details or tasks to be performed that are associated with developing specific traffic control plans, designing interfaces to exchange information between systems, developing control algorithms, or implementing plans to coordinate traffic on and between freeways and surface street roadways.

FHWA-HRT-06-095