U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

|

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-06-095

Date: May 2006 |

The purpose of this chapter is to expand on the corridor-level framework recommended for planning, developing, and operating plans and procedures to support coordinated operation of traffic on freeways and arterials. This chapter assumes that the necessary regional-level planning has been completed, and now the region is ready to begin planning for coordinated operations on specific corridors. Upon completing this chapter, the reader should have a thorough understanding of the issues and processes associated with achieving coordinated operation of freeways and arterials on a specific corridor through implementation of the steps in the CFA framework.

The previous chapter made the case that the chances for success in coordinating the operations of freeway and arterial streets improve when first taking a broad, regional view of solving some of the coordination and institutional issues between agencies. One of the results of this regional-level planning process is the identification of corridors that

| Adhering to a process ensures that all planning considerations are addressed and the potential for realizing the noted benefits of this framework are maximized. |

have operational problems that would benefit from CFA operations. The regional-level planning process provides sufficient information to move forward to the detailed corridor implementation planning process, which is the focus of this chapter.

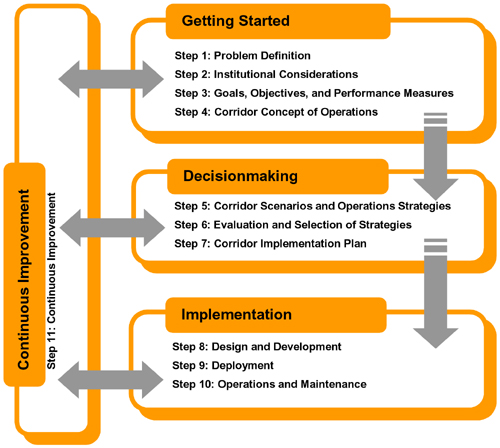

A process roadmap, or framework, was developed to aid agencies and regions in planning, developing, and operating CFA operations for an individual corridor. Figure 6 displays this corridor-level CFA operations framework. The 11-step process may at first glance seem complex or unnecessary. However, adhering to a process ensures that all planning considerations are addressed, and the potential for realizing the noted benefits of this framework are maximized:

Figure 6. Chart. The coordinated freeway and arterial (CFA) operations framework.

The remainder of this chapter discusses each of the 11 steps in the CFA operations framework in more detail.

The first step is to define the problem. A problem may be identified either through a formal performance monitoring process, which may be part of a regional planning process, or as the result of an obvious operational problem such as traffic backing up onto a freeway due to an improperly timed arterial signal.

The definition of the problem in the broadest sense begins at the regional planning and coordination stage. The regional planning process provides the institutional framework necessary to sustain the corridor planning process. At the regional level, problems are identified at a minimal level of detail as part of a planning and programming function. At the corridor level, discussed in this section, a more detailed level of problem identification is undertaken.

The cause of a problem may be easy to identify at the regional level, such as the lack of traffic signal coordination between two adjacent jurisdictions. However, at the corridor level, problem definition may require more extensive analysis, especially when the congestion is widespread, to determine the true bottlenecks in a system experiencing extensive congestion. While it is easy to measure and identify symptoms of problems, the key is to identify the root causes of congestion in the corridor.

There are four types of problems that are particularly amenable to coordinated corridor operations:

Incidents on freeways are the most readily addressed form of freeway congestion. Traditional actions like motorist service patrols that focus on quickly removing incidents, directly mitigate the effects of incidents. However, incidents may have significant secondary effects in major travel corridors, resulting in diversion to arterial streets which, if unprepared for the influx by unadjusted signal timing or other factors, can result in sprawling congestion on major thoroughfares.

More significant corridor problems are also likely to result from major construction projects in work zones that require closed lanes, detours, or other modifications to roadway usage patterns. Special events can generate large traffic volumes, often at what would otherwise be off-peak times, creating congestion due to suddenly increased volume and, perhaps, unusual traffic patterns as large numbers of vehicles attempt to reach the same destination at the same time. The resulting corridor congestion can often cause significant delays to travelers who are not involved in the special event. The benefit of coordinated operations is that travelers will avoid the delays caused by special events.

Day-to-day operations, while of little note, are perhaps the most sensitive to the iterative process of continued fine tuning to achieve optimum benefit. Issues related to these four specific problem types will be discussed in chapters 5.

Initially, processes may not be in place to identify problems based on performance measurement systems (e.g., freeway and arterial performance measurement systems using detection and data archiving). Problems will be identified by more ad hoc systems, such as travelers registering their concerns with public agencies; however, public agencies often discard problems brought to their notice as being outside their jurisdiction. Problems initially identified at the local level should also be provided to regional-level agencies for consideration.

Finally, what one stakeholder sees as a problem may not be viewed as a problem by other stakeholders. For example, some local jurisdictions may object to accommodating freeway diversion traffic. However, lack of an initial consensus does not mean a solution cannot be reached. The goal of this phase of the process is to create an environment where mutual problem identification is possible as the first step towards resolution. The next critical step is developing the framework to work through the solutions. The institutional framework must provide a level playing field where all stakeholders—all parties who have an interest in a safe, efficient transportation corridor—explore issues and find win-win solutions. Coordination cannot take place when one or more participants are placed in what they perceive to be a situation where they will be obligated to contribute to a solution which is either inconsistent with their agencies' goals or contradicts their agencies' interests.

|

An overarching structure is necessary to bridge the seams between the various agencies and even functions within agencies. |

It is necessary to establish an institutional structure for the specific corridor being addressed in the coordinated operations framework. The institutional structure can be ad hoc or formal depending on the current state of coordination in the region and the complexity of the undertaking. Ad hoc arrangements tend to work best when long-term relationships between entities already exist or when the effort emerges from a specific project of limited duration. Formal agreements are used when either the complexity of the endeavor or the long-term nature of the undertaking require that the effort be implemented with formal agreements. There is no single best practice because of the unique nature of each region. The important point is to realize that an overarching structure is necessary to bridge the seams between the various agencies and even functions within agencies.

Mechanisms for creating institutional structures may include personal relationships among leaders and staff members of key operating agencies and neighboring jurisdictions who recognize common problems and opportunities and agree to work together to improve corridor performance. These structures may evolve from or into a broad-based regional partnership among public and private sector interests across multiple jurisdictions.

A formal organization can be legislatively established as a regional authority, or it can be established by a memorandum of understanding as a virtual organization. An example of a formal organization is metropolitan New York's Transportation Operations Coordinating Committee (TRANSCOMsm), which was formed within the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. TRANSCOM is a coalition of 16 transportation and public safety agencies in the New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut metropolitan region that provides a mechanism to facilitate collaboration and coordination among a variety of existing organizations, but does not replace them. Each existing organization has a specific, unique mission as well as a legal basis for existence and funding. The role of a formal organization is to provide a legitimate basis for collaboration and a mechanism to fund that collaboration.

Virtual organizations may be easier to establish than formal organizations and can rely on member organizations for corporate functions such as procurement, project management, and staffing. A virtual organization may look like a single entity to external observers, but behind the scenes, it will often be comprised of several different agencies and groups working together to produce and deliver specific products and services. An example of a successful virtual organization is AZTechTM. AZTech is a partnership of more than 75 public and private organizations led by the Maricopa County Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Arizona DOT whose goal is to use ITS to improve management of traffic and travel in the Phoenix metropolitan region. The partnership is able to share information through an integrated traffic management and information system consisting of cameras, traffic detectors, DMSs, CCTV, and personal communications devices designed to provide real-time travel information to travelers and traffic managers alike.

|

The role of a formal organization is to provide a legitimate basis for collaboration and a mechanism to fund that collaboration. |

To be effective, the collaboration and coordination must be linked to the regional transportation planning process. Often, what passes for collaboration is directed primarily or solely toward installing a project, solving a problem, or preparing for a special event. For corridor collaboration and coordination to work, it must be part of an ongoing, intentional, focused effort to improve system performance by identifying needs and opportunities and collaborating on strategies and solutions that lead to strategic investments.

There is no one institutional structure that will meet the needs of all local circumstances. It is necessary to bring together the appropriate stakeholders and understand their individual needs and capabilities as well as their authority relative to the collaboration. While there is not one best structure, solutions can be found to virtually all limitations that any one agency may have in achieving collaboration and cooperation.

The success of a corridor initiative depends on participation by an appropriate set of stakeholders. Involving appropriate organizations at the early stages of the decisionmaking process facilitates their buy-in.

Corridor stakeholders' interest in improved operations will vary dramatically. In areas that have implemented substantial traffic management systems, the stakeholders may have an existing working relationship. As a result, these areas usually have operations management committees that provide a natural forum in which to discuss corridor traffic management.

Other areas require more significant education and outreach efforts to assemble and motivate potential stakeholders. Educating the right people is important. Frequently education and outreach efforts target management levels in an organization where decisions are made to commit valuable personnel that support the corridor traffic management development effort. Without management support, it is difficult or impossible for those with a working knowledge of operations in the area to participate in corridor traffic management.

It is often best to start with a core stakeholder group and then add participants to the core group over time. Too many stakeholders at the beginning can hinder the development process and discourage people with limited vested interest in corridor traffic management. Alternatively, it is also important to understand that it is difficult to get buy-in when stakeholders are brought into the process at the late stages.

If it is decided to limit the number of participants to a core group initially, set a timeframe to add others. Table 4 provides a list of stakeholder organizations whose participation would be desirable and which may provide representatives to the group.

It is also important to focus stakeholder participation appropriately. For example, both planners and system operators may participate in the process, but with substantially different contributions. System operators may be more interested in the operational concepts, functional requirements, and interface definitions, while the planners may have more substantial input into identifying transportation needs and services and project sequencing. Other individuals with specialized knowledge will be needed to assist in development of the list of agreements. As the "stakeholder roster" is developed, consider the various areas of expertise that are required and use your stakeholder resources selectively. Different stakeholders should be engaged in different parts of the process, consistent with their expertise and interests.

| Organization or agency type |

Example organization or agency |

|---|---|

| Transportation Agencies |

|

| Transit Agencies/Other Transit Providers |

|

| Public Safety Agencies |

|

| Other Agency Departments |

|

| Activity Centers |

|

| Travelers |

|

| Private Sector |

|

In addition to having appropriate stakeholders, it is necessary to understand their perspectives and issues. One group may focus on minimizing traffic disruptions caused by emergency workers, and overlook the need to protect the personal safety of the responders. However, by hearing all perspectives, problems can often be recast into win-win solutions. Better traffic management becomes improved emergency worker safety and less exposure to potentially dangerous secondary traffic accidents caused by poor traffic management.

The following is a categorical description of potential stakeholders and a representation of their perspectives:

Users are the primary customers of the transportation system. Users include motorized transportation (e.g., motorcycles, automobiles, trucks, light and heavy rail, buses) and nonmotorized transportation, such as walking and bicycling. These customers are interested in safe, reliable, and predictable trips from their origin to their destination. They are generally not interested in the details of how the system operates, except when they encounter a system failure or disruption that influences the convenience or reliability of their trip. Additionally, users want real-time, accurate travel information to guide them on their trip.

Decisionmakers (e.g., elected officials, agency heads, and so forth) develop legislation and policies addressing the funding, implementation, and management of the surface transportation network. They need to understand society's needs and allocate available resources to best satisfy those needs. They also want to know the effects of their allocations.

Responders, such as police, fire, and other emergency services, represent a "special user" category. They use the transportation network as part of their critical missions and often have decisionmaking and operational responsibilities for the network, particularly during traffic incidents, special events, and emergencies.

Practitioners (e.g., agency managers, planners, designers, implementers, operators, and maintenance staff) are responsible for implementing the transportation projects and day-to-day management and operation. They are the providers who supply the many functions and services that require collaboration and coordination. They use the resources provided by the decisionmakers to provide travelers with transportation services, travel modes and options, and information that meet the users' needs. These practitioners represent many different types of transportation agencies, including Federal, State, county, city, transit, and regional organizations.

The action steps necessary to establish a corridor traffic management program include not only identification of stakeholders but also identification of champions.

A champion is an individual who believes in the program and is willing to put in the effort necessary to make it happen. Although a small project may not require high-level champions, the presence of a champion who commands significant resources (staff and funds) is most desirable.

Champions are generally visible because they are proactive in the field of management and operations of transportation systems. A champion must be a stakeholder so that he or she has a vested interest in the outcome. But there is no rule saying that there can only be one champion; indeed, it is beneficial that more than one champion be identified from different agencies or stakeholder groups, including:

Champions need to have, in addition to an interest in the outcome, particular skills that will aid them in breaking down institutional barriers and establishing understanding and respect among the stakeholder group. These skills include:

Once the institutional structure is established, the stakeholders next identify the goals, objectives, and performance measures for the corridor. A goal is defined as a broad statement of the long-term outcomes of the program, such as:

Such goals enable all entities affected by coordinated operations to agree in simple layman's terms as to the purpose of the coordinated operations. Moreover, the development of goals should be a bottom-up process with input coming from the stakeholders. The goal development process provides the opportunity to bring all the stakeholders to the table early in the overall CFA process, leading to a continuing dialog. Goal setting also helps establish priorities and ensures that the coordinated operations program is fully responsive to participants needs. Establishing goals sets the stage for the development of objectives and performance criteria.

The next step is to determine specific objectives. Objectives detail how the goals will be achieved. Objectives are generally measurable because they are precise and quantifiable. An example of a measurable objective might be a reduction in incident-caused congestion by 25 percent.

Table 5 illustrates the relationship between goals and objectives. The establishment of goals and objectives allows stakeholders to reach consensus on what corridor management is attempting to accomplish before getting down to specific operations strategies.

| Goals |

Objectives1 |

|---|---|

| Improve safety |

Reduce crash rate. |

| Reduce recurrent congestion |

Improve traveltime. |

| Reduce nonrecurrent congestion |

Improve traveltime. |

| Improve travel reliability |

Reduce variation in daily traveltime. |

| 1 Typically expressed as a quantitative change, such as percent reduction. |

|

Performance measures are needed to assess the success of efforts to collaborate and coordinate and to identify areas where improvement is needed. The first step related to performance improvement is finding a general consensus that performance measures are needed if corridor performance is to improve. Given this consensus, performance measures relevant to system-users must be developed and accepted as meaningful methods of assessing both the short-term and long-term operation of the corridor. Because corridor operations can be an evolving process that undergoes changes in institutional relationships, technology applications, and policy and procedures, the performance measures themselves may change over time.

The performance measurement process is also an important part of the broader need for continuous improvement. Traffic operations are, by their very nature, a continually changing environment. As development takes place or traffic patterns change, system performance will also change, requiring a reevaluation of current operations. The performance measures provide the mechanism for quantifying the operation of the network and should also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of implemented traffic management strategies and to identify additional improvements. Vehicle-hours of delay would be an example of a congestion-related performance measure.

There is not a single performance measure or a set of performance measures to meet all needs. It is therefore necessary for the stakeholder group to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of alternative measures to meet the varying needs of each approach. The following are some characteristics of good performance measures:

Past definitions of congestion have fallen into two basic categories—those that focus on cause and those that focus on effect. Performance measurements clearly require a definition that addresses the effects, or symptoms, of congestion. Since traveltime or delays are the typical measures, congestion represents traveltime or delay in excess of that normally incurred under light or free-flow travel conditions.

As stated, traveltime or difference in traveltime can be a basic measure. It can be used to compare door-to-door traveltimes by different modes. In addition, travel rate (e.g., minutes per mile) can be used to account for link-specific differences in the transportation network.

Moving to a corridorwide operations approach makes it essential that the performance measures be consistent with the goals and objectives of the process in which they are being employed. It is also important to consider how the performance measures may be used including policy, planning, and operational situations.

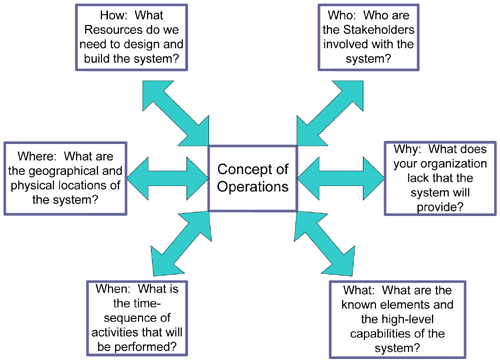

The corridor concept of operations is a formal document that provides a high-level, user-oriented view of operations in a specific corridor. It is developed in part to help communicate this view to the other stakeholders and to solicit their feedback. The corridor concept of operations provides a description of the current system, operating practices and policies, and existing capabilities. It lays out the program concept, explains how the corridor system is expected to work once it is in operation, and identifies the responsibilities of the various stakeholders for making this happen. The goals, objectives, and performance measures of a proposed operation are also documented. The process of developing a concept of operations for a corridor should involve all stakeholders and serve to reinforce the goals and objectives developed in step 3; to provide a definition of how functions are currently performed, thereby supporting resource planning; and to identify the interactions between organizations. Figure 7 schematically shows all of these issues and questions addressed in a concept of operations.

Figure 7. Chart. Questions addressed by a concept of operations document.(12)

By definition, a concept of operations does not delve into technology or detailed requirements of the program. Rather, it addresses operations scenarios and objectives, information needs and overall functionality, details of where the program should be deployed, how users will interact with the various elements of the program, and performance expectations. The concept of operations must also address the "institutional" environment in which the corridor operations program is to be deployed, operated, and maintained. This environment includes all the potential stakeholders and their respective needs and perspectives, the relationships between the coordinated operations program and the policies/procedures of affected public agencies and private entities, and the necessary coordination (working relationships and agreements) between the stakeholders.

The major goals of the concept of operations include:(12)

The most important aspect of this phase is that the questions of who, what, where, when, why, and how are answered. Of lesser importance is the exact format of the final concept of operations document, which should vary to some degree depending on the complexity of the system(s) and resources available to document the issues covered during this stage. While there is no standard outline for a concept of operations document, there are a number of core elements that a good concept of operations should cover that could be used as a high-level outline for the final document. These core elements include:(12)

Chapter 4 presents examples of how these core elements can be incorporated into a corridor concept of operations for corridors that are dealing with problems related to incident management, work zones, special event management, and day-to-day operations.

The corridor concept of operations can be thought of as "a vision of what we want to do," while step 5 can be thought of as "a vision of how we want to do it." This step takes the corridor concept of operations to a more comprehensive level by developing more detailed corridor scenarios and then identifying specific operations strategies to address these scenarios.

The first part of this step takes the description of operations scenarios developed in the corridor concept of operations to a more detailed level. It is important to develop a range of operations scenarios to an adequate level of detail that can be used to determine which operations strategies are needed. These detailed scenarios need to represent the range of conditions that could occur in the corridor.

Table 6 displays examples of how the high-level scenarios developed in step 4 can be taken to a more detailed level in step 5. The detailed corridor scenarios should be developed with the assistance of, or at the least the concurrence of, the stakeholders. Key considerations in the development of scenarios include:

| Opportunity for Coordination |

High-Level Scenario (From Concept of Operations) |

Detailed Scenarios |

|---|---|---|

Incident Management |

Fatal crash on I-90 freeway during p.m. peak |

|

Work Zone Management |

I-90 freeway lanes closed during construction |

|

Special Event Management |

Sports event creates queues on freeway blocking exits to local businesses/neighborhoods |

|

Day-to-Day Operations |

Freeway bottleneck causes vehicle diversions onto parallel arterial during p.m. peak |

|

Once the more detailed corridor scenarios have been developed, then specific operations strategies can be identified that will help mitigate the impacts of the scenarios. Having available the range of possible scenarios will be helpful in identifying potential operations strategies. During this step, strategy identification will be at a conceptual level. Strategies should be identified based on input from the corridor stakeholders. Desirably, the identified strategies are those that will:

In the next step, the identified strategies will be evaluated more rigorously to select the best possible strategies for the corridor. The types of strategies that are appropriate for coordinated operations on a corridor can be grouped into three categories:

The difference in perspective for the strategies above is they are viewed from a corridorwide perspective. The following discussion in this section provides an overview of the range of strategies available for improving coordinated operations on a corridor.

Most regions provide traveler information by one or more traveler information media, but often the information is not coordinated in a corridorwide perspective. Traveler information that is focused solely on a freeway or arterial streets can have either positive or negative effects on the entire corridor. For example, a DMS that suggests using alternate routes due to a freeway incident can potentially have a negative impact on a parallel arterial if appropriate traffic management and control plans do not support potential motorist rerouting in response to the information. Thus, it is easy to see the need for a corridorwide view of traveler information.

In this day of advanced communications technologies, there are a multiple ways to disseminate information among travelers, including:

Figure 8. Photo. Sample DMS message.

The list of ways to communicate traveler information reflects both formal and informal sources of information. Informal sources include the use of CB radios by truckers. Formal sources include DMSs (figure 8) and private sector traffic information providers that broadcast radio traffic services. By expanding the quality and extent of information provided, travelers can implement their own rerouting plans or defer their trips. Either way, the result is improved system performance.

A coordinated view of traveler information has two benefits. First, it does not provoke a negative impact on the system by focusing information on only one part of the system (i.e., the freeway or the arterial). Second, it focuses on traveler information as a system approach to maximizing corridor performance. During peak traffic times, traveler information may cause motorists to delay or even cancel trips, reducing demand. During off-peak times, traveler information may make the system more efficient by encouraging the use of less active portions of the transportation system, which has the capability of absorbing excess demand from the portion of the system experiencing congestion.

Critical aspects of information include the time it reaches travelers (pretrip, en route), the type of information (condition, guidance), the extent of the information (link-based, corridor-based), and the method of dissemination (Web site, radio, HAR, DMSs, trailblazer signs). The more system oriented the information, the better decisions travelers can make.

In addition, the further in advance information can be provided, the more likely a desirable outcome will result. If travelers receive information before leaving home or work, alternative routes are significantly more often used than when travelers are already caught in traffic. A coordinated traveler information strategy would ideally use a single metropolitan area Web site and contain both freeway and arterial travel information. Estimated traveltimes could be provided for alternative routes, along with information on events along all routes. During the middle of the day, information on work zone activities could be provided on a corridor traffic map indicating the nature and location of work zones.

Improving the nature of information provided is also important. Traditionally, because of the lack of coordination between operating agencies, traveler information was largely advisory and only related to the agency owning the DMS. By developing agreed upon operations plans, more specific guidance information can also be provided to help travelers take specific actions, such as taking a diversion route around a freeway incident.

One particular issue to decide is whether to provide route guidance as part of the traveler information system. Dynamic route guidance around particular incidents, work zones, or other causes of congestion is particularly beneficial to motorists when taking a corridorwide perspective. However, providing route guidance is difficult for a number of reasons. Among the issues to consider are the availability of real-time information on both the original route and alternate routes, the amount of capacity available on alternate routes, the infrastructure needed to provide dynamic route guidance (DMSs, trailblazer signs, static signs, and so on), the potential response of motorists to the guidance (e.g., a large percentage of motorists unfamiliar with the surroundings may not be willing to change routes), and the impacts on neighborhoods and local businesses. Once a decision is made to provide dynamic route guidance, choosing specific alternate routes can also be difficult. A survey of public agencies revealed the top 10 criteria used when selecting alternate routes: (13)

A coordinated traveler information strategy includes shared use of information systems. For example, a freeway DMS that typically provides traffic information on the freeway could also provide information on congestion on nearby streets caused by incidents or special events. Real-world examples are evident in the Phoenix, AZ, and Washington, DC, metropolitan areas where DMSs located on arterials adjacent to freeways provide congestion information on the freeways, giving motorists the opportunity to avoid the congestion before entering the freeway. Without a broad view of traffic management, the DMS does not achieve its maximum potential as a corridorwide traveler information system.

Overall, achieving a corridor approach to traveler information dissemination requires a broader look at the available systems and the interconnections necessary to implement the corridor information program. Issues that may need to be addressed include center-to-center communication and shared control of traveler information systems such as Web sites and DMSs. A coordinated traveler information program may require the development of cooperative agreements. A cooperative agreement is a formal statement of recognition and commitment by the participating agencies regarding their roles and responsibilities in the operations of the corridor. Such details are finalized in step 8 of the CFA operations framework.

Traffic management and control strategies can be divided into three categories:

Traffic signals are operated by the responsible local jurisdiction or its designee. However, the boundaries of these operating agencies often do not constitute logical break points in a traveler's journey; therefore, one simple means of improving corridor operations is to develop timing plans jointly in a way that reflects the users' systemwide view of travel.

The simplest opportunity to coordinate operations is expanding traffic signal timing issues beyond individual agency boundaries. This can be accomplished in many different ways depending on the specific situation. An example of this would be in an area where a city agency controls all the traffic signals approaching an interchange, and the State operates the two traffic signals at the interchange. The State traffic signals could be added to the city system for coordination purposes by extending the traffic signal interconnect if the agencies have compatible equipment. Such an arrangement does not require one agency to give up control; it is only necessary to allow another agency to provide the necessary coordination functionality. The technical issues involved in such coordination include establishing the necessary communications infrastructure and forming agreements on the coordination timing parameters. Institutional issues could include development of formal agreements, if necessary, and procedures to address how the two agencies resolve any operational and maintenance problems that may arise.

The means for implementing cross-jurisdictional traffic control can vary from a simple agreement to operate a common time reference, cycle length, and offset, to more sophisticated integrated systems. The more complicated the timing strategies, the more sophisticated the traffic control system needs to be, but simple solutions are also possible in many cases. For example, peak-hour coordination can be achieved easily by using pre-arranged timing plans with a common reference time. Preplanned incident response plans can be implemented in a number of ways, including via simple telephone calls to the collaborating agency. Another option would be to grant limited control access to the collaborating agency, especially when one agency has 24-hour/7-day-a-week operations, and the other does not.

Another boundary between subsystems occurs between freeway control systems and arterial control systems. These boundaries can cause operational problems because of uncoordinated day-to-day operations or as a result of nonrecurring congestion affecting normal traffic. As noted previously, any effort to alleviate congestion on one system without taking into account the impact of diverted traffic on other systems in the corridor can have a significant negative impact.

In systems without coordination, it is possible to have a situation where traffic signal control on an arterial favors arterial coordination and ignores traffic exiting the freeway. As a result, there is no information on the impacts of the arterial signal timing on freeway operations. However, a more integrated system would provide feedback to the arterial control system about excessive queues spilling back on the freeway and provide the option to adjust signal timing accordingly to alleviate the backup.

Another example of subsystem interaction is ramp metering. Ramp metering considered in isolation from adjacent signal timing can adversely affect both ramp metering and the traffic signal operations. If the traffic signal discharges traffic onto the ramp in large groups because of long cycle lengths, the meter may have to go to less restrictive metering to discharge the queue, reducing the effectiveness of the ramp metering (figure 9). If restrictive ramp metering backs up traffic onto the arterial, arterial operations may suffer, negatively impacting the overall system performance.

The types of strategies used to coordinate signals effectively within a corridor include local, areawide, diversion, and congestion strategies.

Figure 9. Photo. Uncoordinated arterial signals can cause reduced effectiveness of ramp metering on freeways.

Local Coordinated Strategy. This mode of operation implies the need for a close and responsive interaction between the ramp meter controller and the traffic signal controller. The ramp-metering rate should be adjusted based on the current traffic signal timing at the interchange. Signal timing may also be modified based on current ramp metering rates, whichever is more critical at that time.

Areawide Integrated Strategy. This is a traffic-responsive strategy that sets metering rates based on corridor flow rather than local conditions at the interchanges. The areawide strategy also requires frequent adjustments in traffic signal timing plans as well as ramp metering rates to react to short-term stochastic changes in traffic flow.

Diversion Strategy. The diversion strategy is designed to handle incidents by assigning special timing plans to both arterial traffic signals and ramp meters at locations affected by the diversion strategy.

Congestion Strategy. When traffic demand exceeds capacity in a portion of the corridor, the objective of the traffic control strategy will be to manage the spread of congestion rather than the demand. The goal is to minimize the adverse effect that the congestion has on overall system performance by controlling the location of queues.

Lane use is often set up based on peak-hour traffic and is prescribed by static signing. This approach generally meets routine needs, but is not responsive to changing traffic conditions. Dynamic lane assignment signs may be an appropriate treatment for locations with variable traffic as well as for areas that suffer congestion due to traffic incidents or special events.

Figure 10 illustrates a dynamic lane assignment location on a freeway frontage road. The location could also be a more typical freeway ramp to an arterial where the normal operation is a single lane turning right. Under a certain event (e.g., incident, work zone, or special event), the strategy might include converting the right turn to a double right turn. The strategy would be effective, however, only if the receiving roadway network was timed to accept the extra traffic caused by the event. This type of strategy could also be used during different times of day to reflect different traffic patterns.

Figure 10. Photo. Dynamic lane assignment on an arterial.

These changes might be routinely implemented based on time of day, so that hourly variations in traffic can be addressed. With the appropriate control systems, dynamic lane assignment could also be used for nonrecurring events to improve corridor operations.

Lane-use control can also be provided on freeways to improve incident management, traffic flow, or to improve merging capacity. These techniques can be used to expedite flow onto or off of freeways as part of a CFA management strategy.

Effective lane use should represent current traffic demands, especially when it is at or near capacity. Lane-use control is not as effective in dealing with average traffic demand in a corridor.

Access control can include turning restrictions, ramp metering, or even ramp closure. While ramp metering is an example of limited access control, as are turn restrictions, a variety of measures can be taken to restrict access. Gates on either entrance or exit ramps to or from freeways are a means of controlling access. This can be done using traffic control devices that are deployed on a temporary or permanent basis.

CFA management deals with access control to the corridor level. From this perspective, the most important goal is the effective use of available traffic capacity. The success of any access control strategy within a corridor, however, will depend on the scenario being addressed.

Sharing information and resources across and within agency boundaries takes the concept of a shared, coordinated system to a more comprehensive level of integrated corridor operations.

Perhaps the simplest examples of sharing are those that involve information. Information can be shared in a variety of ways from simple telephone exchanges to electronic pager and e-mail notifications. The information to be shared can also vary from the awareness of an incident to notification of the implementation of a specific operations plan.

An example of information sharing would be an incident report from a freeway traffic management system that is shared by way of an e-mail to the city traffic signal control center. The shared information could provide insight into such potential solutions as traffic diversion to parallel routes.

Sharing surveillance cameras among agencies is an example of a shared resource that could allow another agency to gather information. For example, a freeway surveillance camera at an interchange could provide the arterial management agency with information on street conditions without the need to invest in their own camera.

Figure 11. Photo. A freeway TMC collects and shares information from many sources.

Other resources that could potentially be shared include various incident response equipment such as service patrols, wreckers, and portable DMSs. Application of shared resources of information would be most valuable, for example, in the case of a special event where one agency may not have sufficient assets to manage the situation effectively.

Shared operations could allow an agency with a 24-hour/7-day-a-week operation (figure 11) to take preplanned actions using another agency's equipment when the owning jurisdiction is not staffed. Limited operational control might even be given to a nontraffic agency such as the police during hours where the traffic agency does not staff their traffic operations center. The goal is to maximize the public investment by sharing resources to provide the best operation of the system.

Once a number of potential operations strategies have been identified, an evaluation of the strategies ensures that the most appropriate strategies are selected. The evaluation process and criteria should reflect the goals and objectives that were established earlier and can vary from simple to complex. Strategies that require multiple stakeholders are more complex because of competition for resources. As a result, the details of a particular strategy may have profound effects on how a project is ultimately viewed by stakeholders as a group. It is therefore necessary to have a flexible approach to selecting potential strategies and understanding that all parties must be willing to support the strategies to be implemented.

The evaluation required for larger projects may include an assessment of the costs and the benefits of the project. The structure and formality of the evaluation process used to assess the costs and benefits of the alternatives will depend on the complexity and coordination needs of each agency.

In addition to complexity, the appropriate evaluation process should take into account several other considerations, including existing planning processes in the region. The assessment needs to reflect the evaluation and selection process already used by agencies for other types of program development. Some strategies, like coordinating signals across jurisdictional boundaries, may be simple depending on existing equipment and staff resources, and implementation may be accomplished in-house using existing resources to develop and ultimately implement the new plans and procedures. More extensive control strategies can require more comprehensive analysis to justify the expenditures required for design, implementation, operations, and maintenance.

Strategy evaluation may incur a high cost relative to the expense of actual CFA plan implementation and maintenance. For example, large or complex projects may use a traffic microsimulation model, which can require considerable time and resources to use correctly. Costs of performing a traffic analysis should be considered when estimating the overall costs of a CFA plan for a corridor.

There are various ways to prioritize and select alternative strategies, including many traditional economic analysis tools like benefit/cost ratios. Categories of funding are often created to address specific problems such as safety or capacity. Others use rankings based on weighted evaluation criteria. The criteria should represent the goals and objectives of the local area, with relative importance being reflected in the weights. Criteria could, for example, include improved system performance and improved air quality.

The last element of the evaluation is matching the expected outcomes with the corridor goals and objectives. The evaluation results should be expressed in the same terms as the performance measures developed earlier in the process. These performance measures can be used to determine whether the proposed strategies meet the corridor goals and objectives. While a certain strategy may be ranked the highest in terms of meeting the specified objectives for the corridor, the evaluation should also consider:

Overall, the evaluation and selection process can be simple or complex, but it should at least apply an appropriate traffic analysis tool, apply valid analysis methodologies, be understood and approved by stakeholders, and ensure the selection of realistic, effective, and efficient strategies that meet the goals and objectives for the corridor. Detailed information on selecting the appropriate traffic analysis tools and applying the tool correctly can be found at the FHWA Traffic Analysis Tools Web site: http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/trafficanalysistools/index.htm.

Upon selection of the operations strategies for the corridor, the next step is development of the corridor implementation plan. The purpose of the corridor implementation plan is to provide enough detail so that agencies can proceed to developing operations plans and procedures and designing systems and technologies that support the plans and procedures. The corridor implementation plan is a document with two essential functions: 1) it summarizes all work completed up to this point to serve as a reference for all interested parties if strategies are not designed and implemented immediately, and 2) it provides a roadmap for recommended funding and implementation of the individual projects needed to support the corridor operations strategies. To support this second function, the corridor implementation plan should define expectations over time (what is to be accomplished), processes (how it will be accomplished), and resources (investments in time, money, staff, and equipment).

Corridor operations rely on activities and relationships that can occur only if individuals and organizations commit appropriate funding, staff, and possibly equipment. Implicit in this statement is the allocation, and possible sharing, of resources that enables a region's operators, service providers, and other stakeholders to improve system performance. Operations must be viewed as a resource priority by participating organizations. The corridor implementation plan should address the availability of resources for putting a concept of operations into practice, implementing agreed upon strategies, and sustaining operations on an ongoing basis.

Most funding for operations will come from individual agency budgets. This may involve agreements to share key resources (equipment and personnel) across jurisdictional boundaries or among operators or service providers; agreements on acquisition and procurement that ensure interoperability and standard protocols for communications and data exchange; or potentially, the identification of capital investments in operations-related infrastructure (networks, operations centers, sensors) to be deployed on a regional basis or in conjunction with other capital improvement projects. Funding for such projects requires that operating agencies and service providers have a role in the region's capital planning process. The corridor implementation plan is the vehicle for securing specific project-related funding to implement the corridor operations strategies.

Another value of the corridor implementation plan is that it provides a record of the process. As staffs change, the plan provides the necessary details that allow others to pick up the plan and not have to revisit the steps leading up to the plan. This does not mean that the plan needs to be static. Plans will always need to be updated based on changing circumstances, but even so having a corridor implementation plan will provide the background on how strategies were developed and whether or not they need to be updated.

Overall, the corridor implementation plan is a document that provides complete details on the first six steps of the coordinated operations framework. The exact format of the corridor implementation plan is different depending on the size and complexity of the coordination required; however, an example of the elements that could be included in the corridor implementation plan document includes:

A corridor implementation plan becomes a real benefit when funding sources are not immediately secured and thus design and implementation will be delayed. In these cases, having a record of the process and results is imperative, as well as providing a roadmap for project funding and implementation. If adequate funds are already secured and agencies are ready to go directly into the design and development stage, a formal corridor implementation plan may not be necessary.

The design and development phase translates each of the various projects included in the corridor implementation plan into workable project plans. This phase consists of two primary components: developing operations plans and procedures to accomplish the selected operations strategies and designing the systems and technologies (hardware, software, telecommunications, ITS and traffic control field devices, etc.) needed to support the plans and procedures. Because this document is not intended to serve as a detailed technical manual on systems design, details such as how to design various ITS technologies and systems is not discussed here. Rather, this section will focus on the development of plans and procedures needed to support the operations strategies identified earlier in the process.

A plan defines what will be done, while a procedure defines how it will be done. The plan should accomplish the operations strategies selected earlier. However, the operations strategies are fairly broad (i.e., arterial signal timing to support freeway traffic diversion); thus, more detailed plans must be developed to define precisely how the strategy will be implemented. In addition, multiple plans will be needed to respond adequately to the range of scenarios that could occur.

For the example of arterial signal timing to support freeway diversion, multiple signal timing plans will be needed depending on the scenario that occurs. Three different signal timing plans could be created to account for light diversion, moderate diversion, and heavy diversion scenarios. Developing each of these plans includes defining what traffic signals will be affected and what changes will be needed (e.g., the signal offsets, cycle lengths, and green splits could all be changed). It is imperative that the plans be developed in advance so agencies can quickly implement the plans in real time based on the scenarios that occur.

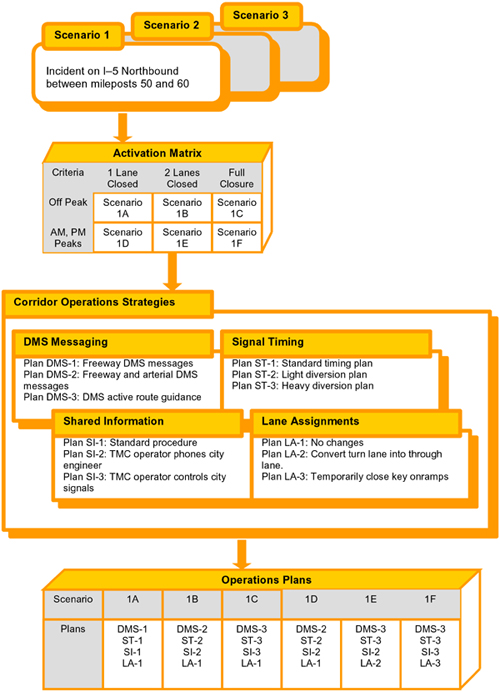

Operations plans are needed for each operations strategy selected; therefore, numerous plans could be created for DMS messaging, signal timing, ramp meter timing, dynamic lane assignment, access management, traveler information dissemination, sharing agency information (e.g., State TMC operator shares freeway conditions with city engineer), and sharing agency resources (i.e., State TMC operator controls city traffic signals after regular office hours). As a result, many operations plans will be created for the corridor. One way to organize the operations plans is to combine them into logical groupings based on each scenario. Figure 12 shows an example of how operations plans can be grouped together based on the operations scenarios and strategies.

Figure 13 shows the individual scenarios developed previously in step 5 of the coordinated operations framework further subdivided into subscenarios (i.e., scenario 1 divided into scenarios 1A, 1B, 1C, etc.). Subdividing the scenarios in this manner may be necessary depending on the level of detail required. In the figure, the scenarios were subdivided using an activation matrix, which in this case is a two-dimensional grid of the number of lanes blocked and time of day of the incident. Various criteria can be considered for the activation matrix based on the event, location, duration, time, and severity/impact of the event as discussed in section 3.7.

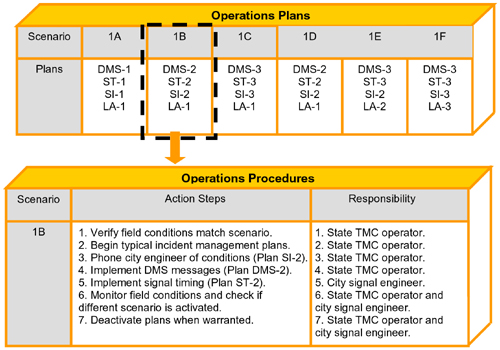

After developing the operations plans, procedures are needed to define how the plan will be implemented. The procedures define the roles and responsibilities for the plan, or who will do what and when should it be done. Specific steps need to be defined for each plan, including when it should be activated, sequence of steps needed to complete the plan, who is responsible for each step, and when the plan should be deactivated. Using an activation matrix such as that shown in figure 12 is one way to detail when a plan should be activated. Figure 13 shows an example of how procedures can be developed and documented based on the various operations plans.

Recognition of existing procedures needs to be taken into account when developing these new procedures and overlap is discovered between what is currently done and what is proposed. For the example in figure 13, the normal incident management procedures by the State TMC operator were incorporated into the corridor operations procedure.

Figure 12. Chart. Example of development of corridor operations plans.

Figure 13. Chart. Example of development of corridor operations procedures.

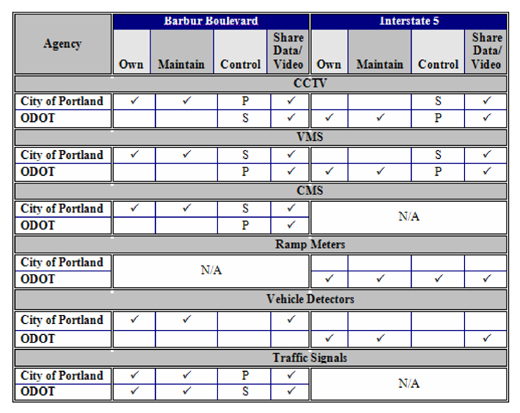

In addition to defining responsibilities for the operations plans, responsibilities should also be defined for those agencies and departments that own physical systems and equipment, whether or not equipment will be shared (and who has control override), and who is responsible for maintenance. Figure 14 shows an example from Portland, OR, where responsibilities were agreed on and explicitly stated in a corridor operations plan.

Figure 14. Chart. Example of identifying field equipment responsibilities.(14)

|

N/A = Not applicable. |

In defining relationships for sharing equipment, it is important to define the boundaries of control before implementing the plans. For example, if one agency has agreed to allow another agency to take control of a CCTV system under specific circumstances, those circumstances must be laid out in the greatest detail possible, delineating both the triggers for handoff as well as the circumstances for returning control to the principle authority. The formality of the definition of the organizational relationships will depend on the complexity of the operations plans and the legal requirements of each organization involved.

Cooperative agreements between agencies (public or private) may be needed to support the plans and procedures developed at this stage. Cooperative agreements can take many forms, such as resolutions, memoranda of understanding (MOU), intergovernmental agreements, or

some combination of these. The cooperative agreements should be agreed upon and signed before the actual implementation of the systems, plans, and procedures. More detail on this subject, including guidance and lessons learned on developing cooperative agreements for corridor management, is available in NCHRP Synthesis of Highway Practice 337: Cooperative Agreements for Corridor Management.(15)

The deployment stage consists of the implementation of plans and procedures and the installation of ITS and traffic control devices, including telecommunications hardware and software. Getting the public involved and aware of the project throughout the entire planning and design process is essential. Prior to starting the system, a targeted public outreach campaign should be implemented where motorists' travel through the corridor will be altered by the corridor implementation plans and procedures. Negative media coverage and/or public complaints to local leaders and elected officials have the potential to entirely shut down a corridor operations project, so it is clear that the public, media, agency management, and even elected officials should be educated on how the systems work, how it affects motorists travel, and the benefits of the system to corridor residents and businesses.

The public outreach should be targeted to motorists who drive through the corridor on a regular basis, who live or have a business near the corridor, and who may be effected by the corridor operations plans. Distributing marketing materials, releasing press statements, granting interviews to television stations and other media, and attending neighborhood meetings are all viable methods to help the public understand the new systems and plans in advance of actual deployment.

Special events and work zone projects often have their own public outreach efforts. When implementing corridor operations plans and procedures into these types of projects, the public outreach should integrate information on the corridor operations systems into the overall special event or work zone project outreach campaign.

New systems and technologies should be field tested under a variety of different conditions and scenarios to ensure that the systems will function adequately before actual implementation of the corridor operations plans. Participating agencies and departments should make sure they are internally ready to operate the systems for which they are responsible. Being ready includes ensuring all responsible staff are adequately trained on the plans and procedures and have adequate time and resources to complete their responsibilities. Being ready also includes notifying affected internal staff, including management, of startup dates and how to respond to any questions or complaints from the public (i.e., knowing who the point of contact is for media inquiries).

Upon deployment of the corridor operations plans and procedures, as well as the new systems or equipment needed to support the plans, it is imperative that agencies use the developed plans and procedures to ensure the corridor operates at peak efficiency. The focus of this entire effort is to create plans and procedures that can be operated on a daily basis, or when triggered by certain scenarios, so operating the corridor should have been adequately planned for and funded by this point.

It is easy, however, for those responsible for operating the corridor systems to lose focus after the interest created during the project deployment fades. Daily activity priorities change as new projects, plans, and procedures become the new "project of the day." To address these issues, it is important that agencies periodically monitor the activities of system operators to check whether the corridor operations plans and procedures are being used as often as they should be and as intended.

A number of operations support tools can also be developed to maximize the efficiency of system operators and the plans and procedures used to operate the corridor. Such operations tools could consist of: (16)

Figure 15. Photo. Traffic signal maintenance crew at work.

In addition to operations, the new systems and technologies deployed to support corridor operations need to be maintained on a regular basis to ensure the systems can be efficiently operated (figure 15). Corridor operations systems may be complex, integrated amalgamations of hardware, technologies, and processes for data acquisition, command and control, computing, and communication. Accordingly, maintenance can be a complex proposition as well, requiring sophisticated approaches and advanced technology. Without adequate consideration of maintenance, inefficiency will begin to develop shortly after implementation of a project.

Maintenance of the systems is a necessity to ensure reliability and proper operation, thereby protecting the investment and enabling the system to respond to changing conditions. Failure to function as intended could negatively impact traffic safety, reduce system capacity, and ultimately lead the traveling public to lose faith in their transportation system. Failure of the system also has the potential to cause measurable economic loss and increase congestion, fuel consumption, pollutants, and traffic accidents.

Maintenance considerations must be an integral part of the process to develop a corridor operations program. Considerations for maintenance include involving maintenance stakeholders, developing a high-level maintenance plan (including maintenance and replacement costs in the life cycle analyses), and identifying maintenance functional requirements early in the process. In this manner, the coordinated operations effort and any enabling systems will include the necessary resources, environment, and procedures to maintain the infrastructure associated with the program.

As emphasized in figure 6 in chapter 3, continuous improvement is iterative and should take place throughout the entire life cycle of a corridor operations project, from planning to design to operations and maintenance. Continuous improvement is the process of monitoring the conditions in the field to determine whether the corridor operations plans are meeting the original corridor goals and objectives. If the goals and objectives are not being met adequately, then revisions need to be made to the plans and procedures to meet the goals and objectives.

The continuous improvement step is often overlooked by agencies in all project types. However, it should be considered seriously because it is the only step solely dedicated to ensuring the project is a success. Also, the continuous improvement step keeps the project accountable and certifies the costs of the project are matched with the highest benefits possible.

Continuous improvement is done soon after deployment of the corridor operations systems and on a regular basis thereafter. For example, the effectiveness of the corridor operations system could be checked on a yearly basis. Continuous improvement should be done on a regular basis because of the dynamic nature of traffic conditions, staff turnover, changes in agency direction, and changes in funding and operations priorities. Because of this dynamic nature, operations plans that are highly effective one year may not be the next year.

If it is determined that it is necessary to re-align the corridor operations closer to the original goals and objectives, the corridor stakeholders should first determine how far back in the process they should return. The point in the framework to which the stakeholders should return depends on the nature of the problem and how far apart the actual conditions are from meeting the goals and objectives. Once the framework has been entered again, all the subsequent steps should also be reviewed to determine if they are affected. For example:

Overall, the process of coordinating freeways and arterial streets through the established framework is never completely finished. Not only will new opportunities arise that will need to be addressed within the framework, but refinements to the existing system will also become necessary as time passes. As the system is being operated and maintained, the system must be continually monitored; it is this monitoring process that will inevitably be the catalyst for setting into motion another cycle of the framework. Without such a framework for monitoring conditions and continuously improvement, the corridor (and the overall system) will fail to perform at optimum effectiveness and efficiency as time passes.

The reader should now have a thorough understanding of the issues and processes associated with achieving coordinated operation of freeways and arterials on a specific corridor through implementation of the 11-step CFA operations framework. The next chapter will demonstrate how the corridor-level approach can be applied to incident management, work zones, special events, and daily recurring operations. While these four categorical areas of traffic operations represent areas of emphasis, other traffic issues and problems may also benefit from the framework described in this chapter.

FHWA-HRT-06-095