U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

|

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

Publication Number: FHWA-RD-98-166

Date: July 1999 |

Guidebook on Methods to Estimate Non-Motorized Travel: Supporting Documentation2.19 Preference Surveys

Descriptive Criteria: What is It? Categories: Purpose: Preference surveys are surveys of actual or potential users, in which respondents are asked to express an attitude or make a choice as to how they would act under certain conditions.(1)Preference surveys can have a wide range of uses in bicycle and pedestrian planning, such as:

The level of sophistication involved in preference surveys can vary significantly. At a basic level, survey results can be used directly to prioritize projects or to estimate the impacts of an improvement. Alternatively, more sophisticated surveys can be developed which can be used alone or in conjunction with other data to develop quantitative models of behavior. The advantages and disadvantages of modeling behavior based on survey results are discussed separately, under "Discrete Choice Models," Method 2.5. Structure: Two levels of preference surveys can be identified: 1. "Attitudinal"surveys ask respondents directly how they would respond to various actions (i.e., would they bicycle if bike lanes were available), or ask them to rate or rank their preferences for various improvements. Attitudinal surveys are relatively easy to design and implement and have been widely used to estimate the potential impacts of bicycle and pedestrian improvements and to determine relative preferences for such improvements. However, attitudinal surveys often significantly overestimate the response to a bicycle or pedestrian improvement, since people tend to be more likely to state that they will change their behavior than to actually do so. Attitudinal surveys tend to be better suited for evaluating relative preferences and for estimating the maximum possible response to an action, rather than predicting actual shifts in travel demand. 2. "Hypothetical choice" surveys overcome many of the biases of attitudinal surveys by requiring respondents to make choices between hypothetical alternatives with varying attributes. Hypothetical choice surveys are generally used to develop discrete choice models and to estimate the relative importance of each attribute (time, cost, presence of bike lanes, etc.) in common terms. While hypothetical choice surveys, combined with discrete choice modeling, are becoming more widely used in non-motorized travel analysis, they have the disadvantage of requiring considerable time and expertise to implement. The choice of alternatives to be presented to each respondent must be made carefully to provide the desired relationships between the characteristics of hypothetical alternatives and the probabilities of choosing each alternative. The results in terms of predicted mode split from the survey sample can then be applied to the general population to estimate total change in number of users as a result of an improvement. The results of preference surveys can also be combined with observed data on actual behavior to develop behavior models. This combined approach has two significant advantages: (1) the alternatives used for the stated-preference portion of the survey can be designed to pivot off the actual behavior of the respondent; and (2) the survey can be designed to provide calibration to reality as represented by what the traveler is currently doing. An example of this approach, as applied to transit access mode choice in the Chicago area, is discussed in the entry on "Discrete Choice Models: Transit Access," Method 2.7. Calibration/Validation Approach: Survey results, in terms of the percentage of people who would switch modes given an improvement, can be compared with the actual number of people switching modes in a case where the same improvement has already been implemented. Inputs/Data Needs: This method generally requires that a survey be conducted of actual and/or potential bicyclists or pedestrians who could benefit from the facility improvement or policy change in question. Alternatively, results of surveys conducted elsewhere can be utilized, if the issues addressed by the survey are applicable to the situation being analyzed. The basic steps in conducting a preference survey include:

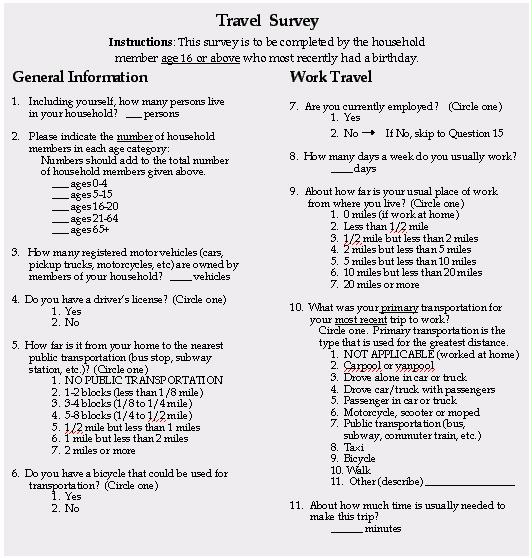

Figure 2.19: A bicycle and walking mode share survey. Potential Data Sources: Previous studies using preference surveys can be used as resources for bicycle and pedestrian planning in other areas. See "Publications" for existing preference survey data. Computational Requirements: Standard statistical software available for microcomputers can be used to analyze survey results. User Skill/Knowledge: Surveys of varying levels of sophistication can be developed. Assumptions: Use of preference surveys to estimate behavior changes assumes that people are able to accurately predict their response to a facility improvement or policy change. Frequently, when people are asked if they will change their behavior in the future, the responses significantly overpredict the number of people who actually change their behavior. Therefore, attitudinal surveys that simply ask people how they will respond in a given situation are not generally viewed as reliable (although they can at least give some indication of the relative response to various actions.) This problem can be largely eliminated through the use of carefully designed hypothetical choice experiments, combined with data on actual behavior if available, although respondents may still not be able to accurately judge what their true actions would be if faced with a realworld situation. If survey results from other areas are used, it is assumed that external factors that may influence survey results, but which are not included in the survey, remain the same in both situations. Facility Design Factors: A variety of facility design factors can be analyzed. An advantage of the stated-preference survey method is that users can be asked questions specific to the design or policy factors under consideration. Output Types: The results of a survey can be summarized and presented in various formats. Examples of survey results include the percent of respondents who would switch to bicycling or walking if a particular improvement were made, and which improvements are regarded by respondents as being top priority. Real-World Examples: A variety of preference surveys have been conducted by States, MPOs, and other organizations. FHWA (1992) and Stutts (1994) document the results of many of these surveys and also discuss the advantages and disadvantages of this type of survey approach. Moritz (1997) conducted a survey of 2,374 bicycle commuters in the United States and Canada. The survey includes socioeconomic and demographic information, commuting habits/trip characteristics, accidents, equipment and facilities used, relative danger by type of street, and motivation. San Diego County in 1994 conducted a survey of 3,800 randomly selected people regarding use of and attitudes toward bicycling. Contacts/Source: William Moritz: University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Jane Stutts: University of North Carolina - Highway Safety Research Center, 730 Airport Road, Chapel Hill, NC, 27514 Stephan Vance: San Diego Association of Governments, San Diego, CA. Publications: Federal Highway Administration (Stewart A. Goldsmith). Case Study No. 1: Reasons Why Bicycling and Walking Are Not Being Used More Extensively As Travel Modes. National Bicycling and Walking Study, U.S. Department of Transportation (FHWA), Publication No. FHWA-PD-92-041, 1992. Moritz, William E. A Survey of North American Bicycle Commuters - Design and Aggregate Results. Presented at the Transportation Research Board 76th Annual Meeting, Paper #970979, January 1997. Stutts, Jane C. Development of a Model Survey for Assessing Levels of Bicycling and Walking, University of North Carolina, Highway Safety Research Center, pp. 1-8, November 1994. Guidelines for survey design and implementation can be found in: Cambridge Systematics and Barton-Aschman Associates. Travel Survey Manual. Prepared for U.S. Department of Transportation and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1996. Dillman, D. Mail and Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method. Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1978. See entries for "Discrete Choice Models" (Method 2.5) for references to other preference surveys. Evaluative Criteria: How Does It Work? Performance: Hypothetical choice surveys have been successfully used to estimate and calibrate models of tripmaking behavior. The performance of such models is discussed under "Discrete Choice Models," Method 2.5. The best use of attitudinal surveys may be for determining relative priorities for improvement. These surveys tend to be overly optimistic in estimating the actual number of new users of a facility (see "Assumptions"). Use of Existing Resources: Use of survey data generally requires data collection efforts specific to the proposed project/policy actions. In some cases, a similar situation may be identified for which a survey has already been conducted. Travel Demand Model Integration: Behavior models based on hypothetical choice survey results can be integrated into travel demand models (see "Discrete Choice Models," Method 2.5). Applicability to Diverse Conditions: A survey designed for a specific situation can be adapted to a wide range of conditions. On the other hand, if data from existing surveys are used, it may not be safe to transfer the results of one survey from one situation to another. When people are asked how their behavior will change as a result of an action, their responses depend on a number of factors specific to the decision in question, which may not be measured in the survey. Designing surveys and using survey results represent a tradeoff. The more specific the questions on the survey to the improvement being analyzed, the more accurate the results. On the other hand, the survey will be less applicable in different situations, and if a different improvement is to be analyzed, new survey efforts may be required. Usage in Decision-Making: No information is available. Ability to Incorporate Changes: See "Applicability to Diverse Conditions." Ease-of-Use: Varies depending on survey type.

FHWA-RD-98-166 |