U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Highway Infrastructure Security and Emergency Management Professional Capacity Building

Download Alternate Versions:

slide 1

Speaker Notes:

Security and Emergency Management for State Departments of Transportation

This briefing was researched and produced as a project by Excalibur Associates,

Inc. in support of prime contractor SAIC under Federal Highway Administration

Transportation Pooled Fund Study 5(161), Transportation Security and Emergency

Preparedness Professional Capacity Building (PCB). Research included a survey

of several State Departments of Transportation (DOTs) and an assessment of responses.

State DOTs and other agencies contributing to the pooled fund were California,

Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, Montana, New York, Texas, Wisconsin,

and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Transportation Security Administration.

Representatives of contributors to the Pooled Fund were concerned about the need for a standard overview to assist in briefing new appointees or senior leaders, especially those that perceive they have no security and emergency management responsibilities or those with little or no experience in those areas, about typical DOT roles, missions, and organizational structures.

This briefing is intended to introduce executives and senior leaders to plans, concepts, and terminology used by the security and emergency management community. It can also serve as a checklist for use in determining the organizational structure, degree of preparedness, and response capabilities of your organization. If you prefer to look at this briefing offline or keep it for reference it might be more convenient for you to print the PDF version.

slide 2

Speaker Notes:

slide 3

Slide Notes:

What is emergency management?

Understanding a common definition of emergency management is the first step.

It encompasses all actions to prepare for, respond to, and recover from a disaster

or emergency. Sometimes you will hear about emergency preparedness or emergency

response. Remember, these are emergency management functions, not stand alone

activities.

slide 4

Emergency Management is a Process

Slide Notes:

Emergency Management Process

Stated in another way, emergency management is the continuous process by which all individuals, agencies, and levels of government manage hazards in an effort to avoid or reduce the impact of disasters resulting from the hazards. There are four (4) phases:

slide 5

Emergency Management is a Process

Slide Notes:

Emergency Management Process

State DOTs have a role in all four (4) phases of emergency management.

slide 6

Slide Notes:

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has a hazard mitigation assessment and planning process for local officials to use to conduct hazard assessments and create plans for mitigating the hazards.

It is important that these assessments and plans include transportation infrastructure. Funding for transportation infrastructure mitigation will normally come from sources other than FEMA resources. Transportation infrastructure should be integrated into overall hazard mitigation assessment and mitigation plans because of the interdependencies of transportation infrastructure with non-transportation infrastructure such as highway bridges carrying communications lines or rail lines carrying fuel for power plants.

Mitigation of transportation infrastructure may occur under the oversight of the State DOT, depending on the State and the type of infrastructure. In most cases, it will be done by private contractors, but under contracts managed by the State DOT.

slide 7

Slide Notes:

Hazard Identification

The first step in preparing is identifying the threats and hazards that a State faces. This step provides the answer to the question: What is the basis for the plan? For example, Southern coastal states are particularly vulnerable to hurricanes, while Midwest states are vulnerable to floods and tornadoes, the West Coast and Midwest must plan for earthquakes, and most Northern states face severe winter storms. All states face the threat of terrorist or criminal caused incidents and accidents causing chemical spills or contamination from nuclear power plants.

The State DOT responsibility is to identify hazards and threats facing the State's transportation infrastructure. Transportation infrastructure is particularly vulnerable to a variety of hazards and threats, including:

slide 8

Slide Notes:

Planning

Governments take an all-hazards approach when planning. Response activities tend to be the same regardless of the event – life-saving, minimizing damage to infrastructure, caring for peoples' needs. However, because there are small differences depending on the specific hazard, States develop plans describing how they will respond to the affects of particular hazards/threats when they occur.

States plan to support local government response efforts because initial response occurs at the local level and local governments do not have extensive resources to support response operations. States also plan to support other states. No State agency can respond completely independent of other organizations and preparedness efforts must be coordinated between agencies.

States also need to plan to receive and use resources provided by other States and the Federal government during response operations.

The State DOT will coordinate planning efforts with other State agencies, including the State's Emergency Management Agency; county highway departments; with various agencies of the U.S. Department of Transportation; and, with DOTs from other States to ensure response activities can be easily integrated when necessary.

slide 9

Slide Notes:

Training

Once the plans are developed, individuals and teams need to be trained to execute the various aspects of the plan. Generally, individuals are trained in their tasks, then teams are brought together to train on integrated tasks.

Training may be classroom, at the DOT or another location; on-line through the Federal Emergency Management Agency or other organization; or may occur on the job to build depth in an Emergency Operations Center (EOC).

Exercising

Exercises are controlled activities conducted under realistic conditions to provide an opportunity to test one or more parts of response plans. They are also used to validate the effectiveness of training of individuals and teams. Exercises are conducted prior to real events so results can be examined in depth to determine what changes, if any, need to occur.

After Action Improvement

Information is collected during and following actual response operations and exercises to determine how well the plan worked and what future training may be needed. The planners take the information, analyze it and make changes to plans and training curricula to ensure better response operations in the future.

slide 10

Slide Notes:

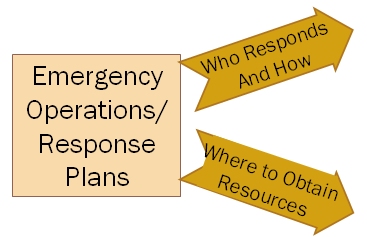

Emergency Operations Plans

Once threats and hazards have been identified, plans can be written. Plans generally address the areas of:

All levels of government – local, tribal, State and Federal – as well as their departments and agencies, prepare formal Emergency Operations Plans (EOP) to establish responsibilities, authorities and procedures on how the entity or organization will operate in response to an emergency or disaster. Your State may call it an Emergency Response Plan, but it is the same thing.

Operations or response plans address:

slide 11

Guides how the nation conducts all hazard incident response.

Slide Notes:

The National Response Framework (NRF) is a guide for how our nation conducts national all-hazard incident response, not just a Federal response.

It incorporates lessons learned from real world operations for natural disasters and other threats, such as the 2005 Hurricane Season, special events, and the London bombings, as well as from national, state and local exercises.

It is focused on response; not on prevention, protection, or long-term recovery.

It is a guide – not a plan.

slide 12

Slide Notes:

National Response Framework

NRF guides by integrating the first three key concepts:

slide 13

Slide Notes:

National Response Framework

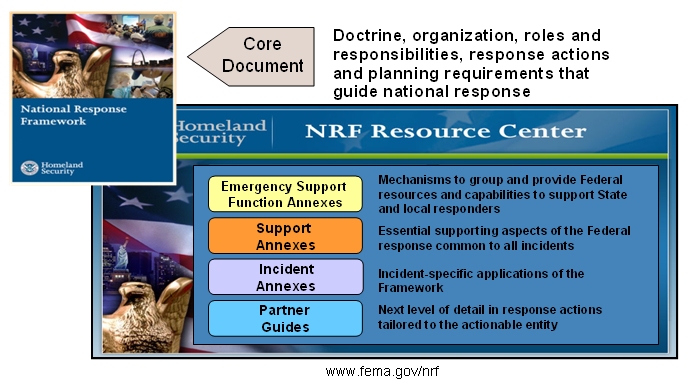

The NRF is comprised of two integrated parts: a printed core component and an on-line component.

The printed core document: The core document (http://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nrf/nrf-core.pdf) is the heart of the Framework. It describes response doctrine and guidance; roles and responsibilities; primary preparedness and response actions; and core organizational structures and processes.

The on-line component: The NRF Resource Center (www.fema.gov/nrf), contains supplemental materials including annexes, partner guides, and other supporting documents and learning resources. This information is more dynamic and will change and adapt more frequently as we learn lessons from real world events, incorporate new technologies, and adapt to changes within our organizations.

We will focus on ESF 1, Transportation, later in the briefing.

slide 14

Slide Notes:

National Response Framework

The NRF is written with you in mind – a senior government executive, one who has a responsibility to provide for an effective response – as well as for the emergency management practitioner.

For the first time, the Framework describes five (5) elements of Response Doctrine:

Planning – a critical element of effective response.

slide 15

Slide Notes:

Applying the Framework

Key concept is that the NRF is always in effect and operational elements can be partially or fully implemented.

slide 16

State Governments

Slide Notes:

Stakeholder Responsibilities

The Governor:

State Homeland Security Advisor (HSA). The State HSA serves as an advisor to the Governor on homeland security issues and may serve as a liaison between the Governor's office, the State homeland security structure, DHS, and other organizations both inside and outside of the state. The advisor often chairs a committee comprised of representatives of relevant state agencies.

Director, State Emergency Management Agency. The Director of the State Emergency Management Agency ensures that the state is prepared to deal with large-scale emergencies and is responsible for coordinating the state response in any emergency or disaster.

State Coordinating Officer (SCO). The individual appointed by the Governor to coordinate state disaster assistance efforts with those of the Federal government. The SCO plays a critical role in managing the state response and recovery operations following Stafford Act declarations. The Governor of the affected state appoints the SCO, and lines of authority flow from the Governor to the SCO, following the state's policies and laws.

State Departments, Bureaus, and Agencies. Plan for providing and obtaining support in accordance with State Emergency Operations/Response Plans.

slide 17

Slide Notes:

State Response Structures

State and tribal officials typically take the lead to communicate public information regarding incidents occurring in their jurisdictions. It is essential that immediately following the onset of an incident, the State or tribal government, in collaboration with local officials, ensures that:

slide 18

Slide Notes:

Federal Leadership and the Framework

Key Federal players are:

slide 19

The Framework systematically incorporates public sector agencies at all levels with:

Slide Notes:

Private Sector and Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs)

slide 20

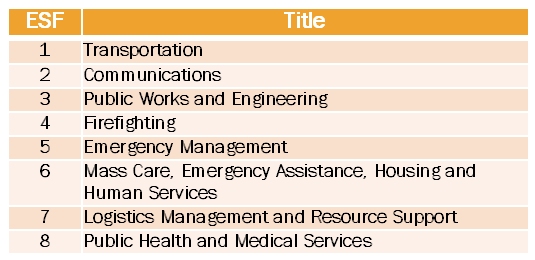

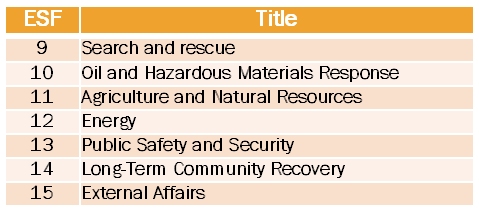

There are the 15 Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) identified in the NRF.

What is an ESF?

Slide Notes:

Emergency Support Functions

The Federal government and many State governments organize much of their resources and capabilities – as well as those of certain private-sector and nongovernmental organizations – under 15 Emergency Support Functions (ESFs). ESFs align categories of resources and provide strategic objectives for their use. ESFs utilize standardized resource management concepts such as typing, inventorying, and tracking to facilitate the dispatch, deployment, and recovery of resources before, during, and after an incident. ESF coordinating and primary agencies are identified on the basis of authorities and resources. Support agencies are assigned based on the availability of resources in a given functional area. ESFs provide the greatest possible access to Federal department and agency resources regardless of which organization has those resources.

During a Federal response, Federal ESFs at all levels are coordinated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) through its National Response Coordination Center (NRCC), Regional Response Coordination Center (RRCC), and/or Joint Field Office (JFO). During a Federal response, ESFs are a critical mechanism to coordinate functional capabilities and resources provided by Federal departments and agencies, along with certain private-sector and nongovernmental organizations. They represent an effective way to bundle and funnel resources and capabilities to local, tribal, State, and other responders. These functions are coordinated by a single agency but may rely on several agencies that provide resources for each functional area. The mission of the ESFs is to provide the greatest possible access to capabilities of the Federal government regardless of which agency has those capabilities.

The ESFs serve as the primary operational level mechanism to provide Federal assistance.

slide 21

DOT is the lead agency for ESF #1, Transportation.

| According to the NRF, the U.S. DOT is responsible for: | As the State ESF 1 primary agency, your DOT might do these types of activities: |

|---|---|

| Monitoring and reporting the status of, and damage to, the transportation system and infrastructure | Inspect or assist in inspecting bridges, roads, rails and/or airfields after a severe flood or earthquake |

| Identifying temporary alternative solutions that can be implemented to ensure that the movement of people and materials can be continued during the response | Establish detours and set up alternate route signs on state highways; clear state highways of debris; clear runways for movement of aircraft; and assist with traffic control and contra-flow |

| Performing activities conducted under the direct authority of the DOT | Close roads, harbors or airfields |

| Coordinating the restoration and recovery of transportation system and infrastructure | Replace bridges and railroad tracks; dredge harbors |

| Coordinating and supporting preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation activities among transportation stakeholders | Participate in training and exercises; work with local governments to rebuild or retrofit infrastructure |

Slide Notes:

ESF 1, Transportation

The U.S. Department of Transportation is the lead Federal agency for ESF 1, Transportation.

The State DOT usually has the leadership role within the state for all matters relating to transportation: infrastructure, including roads, tunnels and bridges; transit systems; airfields; canals; and railroads; as well as for all preparedness activities, response operations, and recovery and mitigation activities related to transportation resources. The ESF lead agency coordinates planning efforts and the use of resources from other state agencies that may be identified to provide support. Your State DOT may support some of the other ESF lead agencies.

At the Federal level Emergency Support Function 1, Transportation, is NOT the primary agency responsible for the movement of goods, equipment, animals or people. However, as each state is organized differently, your State DOT may be involved in these transportation activities to some degree.

slide 22

Slide Notes:

The first eight Emergency Support Functions and Primary Federal Agencies for the Federal government are:slide 23

Slide Notes:

The remaining Emergency Support Functions and Primary Federal Agencies for the Federal government are:

The same ESFs will be identified in most State Emergency Operations Plans (EOP). While the concept of ESFs has been around for a long time, it was primarily a purview of the Federal government. However, with the publishing of the National Response Plan, which was superseded by the NRF, States have begun organizing along the same framework. Some States have identified additional ESFs for their EOPs, so you may hear about ESFs 16, 17 or higher. Some States do not call them by the ESF number; instead, they use the name of the ESF such as Transportation, Communications, or Public Safety. Your state might use some other form of organizing capabilities for response activities.

slide 24

Slide Notes:

The National Incident Management System (NIMS) is a companion document to the National Response Framework (NRF). The NIMS provides a systematic, proactive approach to guide departments and agencies at all levels of government, non-governmental organizations (NGO), and the private sector to work seamlessly to prevent, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of incidents, regardless of cause, size, location, or complexity, in order to reduce the loss of life and property and harm to the environment.

Together the National Incident Management System (NIMS) and the National Response Framework (NRF) have a common goal – the efficient management of incidents and use of resources. NIMS provides the template for the management of incidents, while the NRF provides the structure and mechanisms for national-level policy for incident management.

The NIMS is intended to:

In other words, the NIMS is intended make sure all organizations are on the same page when responding to all types of emergencies.

The NIMS provides the template for the management of incidents, while the NRF provides the structure and mechanisms for the National policy for providing resources and managing the Federal response.

slide 25

Slide Notes:

Why is there a National Incident Management System?

Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD)-5, Management of Domestic Incidents, directed the development and administration of the National Incident Management System (NIMS). Originally issued on March 1, 2004, by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), NIMS provides a consistent nationwide template to enable Federal, State, tribal, and local governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector to work together to prevent, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of incidents, regardless of cause, size, location, or complexity.

NIMS was originally published in March 2004 and received its first true test during the response to and management of the Hurricane Katrina Disaster. Using lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina and other events, a revised NIMS was published in 2008.

slide 26

Slide Notes:

Intent

Consistent use of the NIMS lays the groundwork for response to all emergency situations, from a single agency responding to a fire, to many jurisdictions and organizations responding to a large natural disaster or act of terrorism.

An important effect of the NIMS is that it creates a common approach in both pre-event preparedness and post-event response activities that allow responders from many different organizations to effectively and efficiently work together at the scene of an incident.

Under the NIMS, responders from a wide variety of jurisdictions and agencies know what to expect and what to do when they arrive at an incident scene.

The NRF and NIMS are companion documents that were created to improve the Nation's incident management and response capabilities. Together, the NRF and NIMS provide for the effective integration of the capabilities and resources of various governmental jurisdictions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector incident management and emergency response disciplines into a cohesive, coordinated and seamless national framework for incident response.

slide 27

Slide Notes:

NIMS has five (5) components. Four (4) of these and what they mean to a State Department of Transportation (DOT) are:

The fifth component is Ongoing Management and Maintenance, which is simply the process of ensuring continued coordination and oversight of the program by an element of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

slide 28

Slide Notes:

Incident Command System

The Incident Command System (ICS) is the NIMS element with which you should become most familiar. ICS provides a standardized, yet flexible, management process to ensure all resources committed to a response, whether the resources are provided from different organizations within or outside a single jurisdiction, or, for complex incidents with national implications, are used in the best way possible. When an incident requires response from multiple local response agencies, effective cross-jurisdictional coordination using common processes and systems is critical to an effective response and for the safety of the responders.

ICS allows responders from outside a local jurisdiction or state to volunteer or be sent to another incident scene and still understand the terminology and operations being used. Your people could be sent to an area other than the one they report to on a daily basis, especially during a regional or statewide incident or when those who would normally respond are affected by the situation and external resources need to be brought in to help.

State and Federal governments and departments/agencies also use principles of ICS. This is generally seen in the organizational structures that have common elements to facilitate coordination both vertically – from local to State to Federal – and horizontally – local to local, State to State and between Federal departments and agencies.slide 29

Slide Notes:

Why is there an Incident Command System?

ICS was developed in the 1970s following a series of catastrophic fires in California's wildlands. What were the lessons learned? Surprisingly, studies found that response problems were far more likely to result from inadequate management than from lack of resources or tactics. Weaknesses were often due to:

slide 30

ICS is:

Slide Notes:

What is ICS?

The ICS is designed to:

ICS has been tested and proved effective in more than 30 years of emergency and non-emergency applications, by all levels of government and the private sector.

ICS is comprised of procedures for managing personnel, facilities, equipment, and communications resources. It is a system designed to be used from the beginning to the end of an incident.As a system, ICS is extremely useful; not only does it provide an organizational

structure for incident management but it also guides the process for planning,

building, and adapting that structure. Using ICS for every incident or planned

event helps hone and maintain skills needed for the large scale incidents.

slide 31

Slide Notes:

Incidents

Definition: An incident is an occurrence, regardless of cause, that requires response actions to prevent or minimize loss of life, or damage to property and/or the environment.

Examples include:slide 32

Slide Notes:

There are 14 ICS Management Characteristics

Common Terminology. ICS establishes common terminology that allows diverse incident management and support organizations to work together across a wide variety of incident management functions and hazard scenarios. This common terminology covers the following:

Incident response communications (during exercises and actual incidents) should feature plain language commands so they will be able to function in a multijurisdictional environment. Field manuals and training should be revised to reflect the plain language standard.

Modular Organization The ICS organizational structure develops in a modular fashion based on the size and complexity of the incident, as well as the specifics of the hazard environment created by the incident. When needed, separate functional elements can be established, each of which may be further subdivided to enhance internal organizational management and external coordination. Responsibility for the establishment and expansion of the ICS modular organization ultimately rests with Incident Command, which bases the ICS organization on the requirements of the situation. As incident complexity increases, the organization expands from the top down as functional responsibilities are delegated. Concurrently with structural expansion, the number of management and supervisory positions expands to address the requirements of the incident adequately.

Management by Objectives Management by objectives is communicated throughout the entire ICS organization and includes:

Incident Action Planning Centralized, coordinated incident action planning should guide all response activities. An Incident Action Plan (IAP) provides a concise, coherent means of capturing and communicating the overall incident priorities, objectives, and strategies in the contexts of both operational and support activities. Every incident must have an action plan. However, not all incidents require written plans. The need for written plans and attachments is based on the requirements of the incident and the decision of the Incident Commander of Unified Command. Most initial response operations are not captured with a formal IAP. However, if an incident is likely to extend beyond one operational period, become more complex, or involve multiple jurisdictions and/or agencies, preparing a written IAP will become increasingly important to maintain effective, efficient, and safe operations.

slide 33

Slide Notes:

There are 14 ICS Management CharacteristicsManageable Span of Control. Span of control is key to effective and efficient incident management. Supervisors must be able to adequately supervise and control their subordinates, as well as communicate with and manage all resources under their supervision. In ICS, the span of control of any individual with incident management supervisory responsibility should range from three (3) to seven (7) subordinates, with five (5) being optimal. During large scale law enforcement operations, eight (8) to 10 subordinates may be optimal. The type of incident, nature of the task, hazards and safety factors, and distance between personnel and resources all influence span of control.

Incident Facilities and Locations. Various types of operational support facilities are established in the vicinity of an incident, depending on its size and complexity, to accomplish a variety of purposes. The Incident Command will direct the identification and location of facilities based on the requirements of the situation. Typically designated facilities include Incident Command Posts, Bases, Camps, Staging Areas, mass casualty triage areas, point-of-distribution sites, and others as required.

Comprehensive Resource Management. Maintaining an accurate and up-to-date picture of resource utilization is a critical component of incident management and emergency response. Resources to be identified in this way include personnel, teams, equipment, supplies, and facilities available or potentially available for assignment or allocation.

Integrated Communications. Incident communications are facilitated through the development and use of a common communications plan and interoperable communications processes and architectures. The ICS 205 form is available to assist in developing a common communications plan. This integrated approach links the operational and support units of the various agencies involved and is necessary to maintain communications connectivity and discipline and to enable common situational awareness and interaction. Preparedness planning should address the equipment, systems, and protocols necessary to achieve integrated voice and data communications.

slide 34

Slide Notes:

There are 14 ICS Management Characteristics

Establishment and Transfer of Command. The command function must be clearly established from the beginning of incident operations. The agency with primary jurisdictional authority over the incident designates the individual at the scene responsible for establishing command. When command is transferred, the process must include a briefing that captures all essential information for continuing safe and effective operations.

Chain of Command and Unity of Command.

Unified Command. In incidents involving multiple jurisdictions, a single jurisdiction with multiagency involvement, or multiple jurisdictions with multiagency involvement, Unified Command allows agencies with different legal, geographic, and functional authorities and responsibilities to work together effectively without affecting individual agency authority, responsibility, or accountability.

slide 35

Slide Notes:

There are 14 ICS Management Characteristics

Accountability. Effective accountability of resources at all jurisdictional levels and within individual functional areas during incident operations is essential. Adherence to the following ICS principles and processes helps to ensure accountability:

Dispatch/Deployment. Resources should respond only when requested or when dispatched by an appropriate authority through established resource management systems. Resources not requested must refrain from spontaneous deployment to avoid overburdening the recipient and compounding accountability challenges.

Information and Intelligence Management. The incident management organization must establish a process for gathering, analyzing, assessing, sharing, and managing incident related information and intelligence.

slide 36

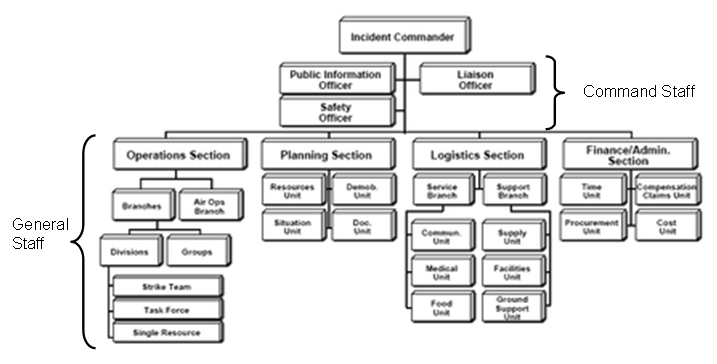

Incident Command Organizational Structure

Slide Notes:

Standardized Organization

ICS organization is standardized and easy to understand. There is no correlation between the ICS organization used for incident response and the day-to-day administrative structure of any single agency or jurisdiction, with the possible exception of the military. This is deliberate, because confusion over different position titles and organizational structures has been a significant stumbling block to effective incident management in the past. For example, one of your supervisors or managers during normal operations, would likely not hold that title when working under the ICS structure.

On the next slide you will see a diagram for a "full up" ICS structure. Remember, the ICS structure begins with appointment of an incident commander. ICS is modular so the incident commander then builds the organization depending on the size, complexity, and requirements of the incident.

slide 37

Slide Notes:

Command Staff. The Command Staff is comprised of the Public Information Officer, Safety Officer, and Liaison Officer. They report directly to the Incident Commander.

Section. Has functional responsibility for primary segments of incident management (Operations, Planning, Logistics, Finance/Administration). Section leaders report to the Incident Commander.

Branch. Has functional, geographical, or jurisdictional responsibility for major parts of the incident operations. The Branch level is organizationally between Section and Division/Group in the Operations Section, and between Section and Units in the Logistics Section. Branches are identified by the use of Roman Numbers, by function, or by jurisdictional name.

Division. That organizational level having responsibility for operations within a defined geographic area. The Division level is organizationally between the Strike Team and the Branch.

Group. Groups are established to divide the incident into functional areas of operation. Groups are located between Branches (when activated) and Resources in the Operations Section.

Unit. That organization element having functional responsibility for a specific incident planning, logistics, or finance/administration activity.

Task Force. A group of resources with common communications and a leader that may be pre-established and sent to an incident, or formed at an incident.

Strike Team. Specified combinations of the same kind and type of resources, with common communications and a leader.

Single Resource. An individual piece of equipment and its personnel complement, or an established crew or team of individuals with an identified work supervisor that can be used on an incident.

slide 38

Slide Notes:

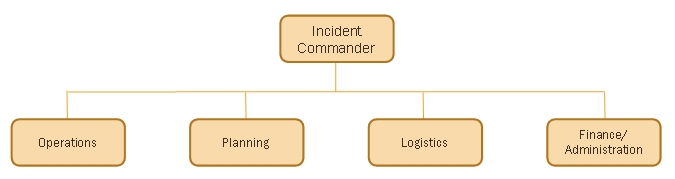

ICS General Staff

There are major management functions that are the foundation upon which the ICS organization develops. These functions apply whether the incident is a routine emergency, is organizing for a major non-emergency event, or when managing a response to a major disaster. The major management functions are:

You may hear these referred to C-FLOP. This is an easy way to remember the first letter of each of the functions: Command, Finance, Logistics, Operations, and Planning.

slide 39

Slide Notes:

ICS Command Staff

Depending upon the size and type of incident or event, it may be necessary for the Incident Commander to designate personnel to provide information, safety, and liaison services for the entire organization. In ICS, these personnel make up the Command Staff and consist of the:

The Command Staff reports directly to the Incident Commander.

slide 40

Slide Notes:

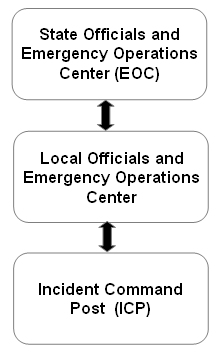

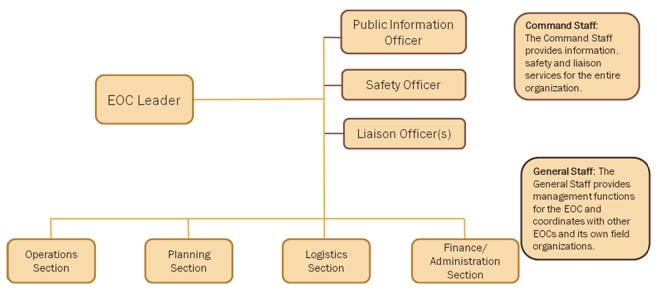

Emergency Operations Centers

An Emergency Operations Center (EOC) is a central command and control facility responsible for carrying out the principles of emergency preparedness and emergency management, or disaster management functions at a strategic level in an emergency situation.

An EOC is found at all levels except at the Incident Commander's location. The Incident Commander's operation center is called the Incident Command Post.

States have operations centers that have either robust staffing from agencies such as the DOT or have representatives from these agencies. Many state agencies also have responsibilities for responding to the State EOC and obtaining and directing resources. Where there is not a robust DOT presence in the State EOC, it is usually necessary for the State DOT have a stand-alone EOC.

slide 41

Slide Notes:

NOTE: The structure depicted is based on ICS, is NIMS-compliant, and is intended to be representative of many State EOCs. Your State EOC may be organized differently.

Your State will have an EOC that is managed by the State Emergency Management Agency. The purpose is to coordinate for and deploy State resources to support local governments. The EOC will also coordinate with other States and with the Federal government for resources.

Federal departments and agencies establish EOCs to manage its resources that are deployed to support incident response operations. The U.S. DOT not only provides ESF 1, Transportation personnel to the NRCC, the RRCC and the JFO, it manages all aspects of ESF 1, Transportation responsibilities as delineated by the NRF. These Federal ESF 1, Transportation representatives may seek to coordinate directly with your DOT representatives in the State EOC, and maybe directly with your DOT EOC.

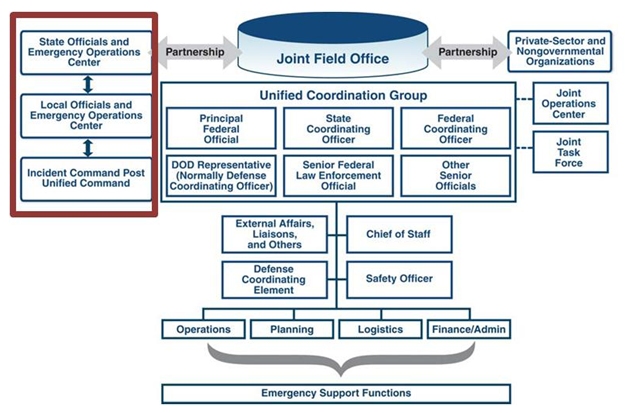

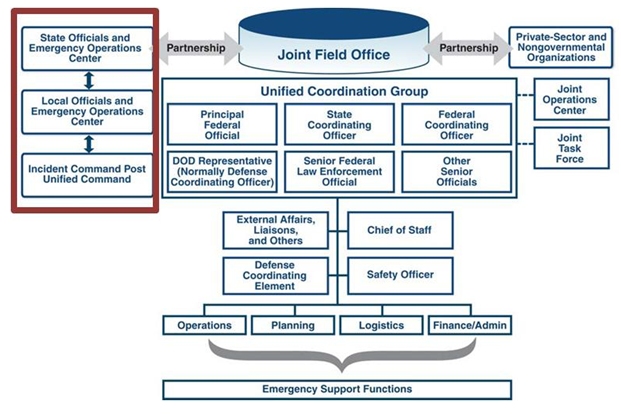

Federal resources are deployed to the vicinity of the incident and managed tactically by the Joint Field Office (JFO). The JFO is organized like an EOC, but instead of an EOC Leader, it has a Unified Coordination Group representing the Federal and State, and sometimes local, agencies that work together to ensure the right resources get to the right place.

slide 42

Slide Notes:

Relationships

The Federal government establishes the National Response Coordination Center

(NRCC) at the Headquarters of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The ESF departments and agencies provide experienced personnel to support the

General Staff sections. They coordinate the mobilization and deployment of Federal

resources to support States responding to disasters and emergencies. The NRCC

is organized in the same manner as the EOC shown.

Each of the 10 FEMA Regional Offices establishes a Regional Response Coordination

Center (RRCC). The organization is the same. The RRCC coordinates and provides

coordination in the very early hours of an incident response. Personnel from

regional offices of departments and agencies provide ESF 1, Transportation support

to the RRCC under the direction of the FEMA Region.

Each Federal department and agency establishes an EOC to manage its resources

that are deployed to support incident response operations. The U.S. DOT not

only provides ESF 1, Transportation personnel to the NRCC, the RRCC and the

JFO, it manages all aspects of ESF 1, Transportation responsibilities as delineated

by the NRF. These Federal ESF 1, Transportation representatives may seek to

coordinate directly with State DOT representatives in the State EOC, and maybe

directly with the State DOT EOC.

Federal resources are deployed to the vicinity of the incident and managed tactically

by the Joint Field Office (JFO). The JFO is organized like an EOC, but instead

of an EOC Leader, it has a Unified Coordination Group that works together to

ensure the right resources get to the right place.

slide 43

Slide Notes:

Coordination

There is a significant amount of coordination that occurs between the JFO and

other organizations. The elements in the box to the left of the Joint Field

Office (JFO) and Unified Coordination Group depict the relationship between

the Incident Command Post, the local government EOC, the State EOC, and reflect

the flow of resources (down), and coordination and information (up and down).

It is important to note that the Federal government does not appear in the coordination

chain between the Incident Commander and the State EOC. This is in keeping with

the concept that “all incidents are managed locally.”

A key member of the Unified Coordination Group is the State Coordinating Officer,

representing the Governor and a direct coordination link between the JFO and

the State EOC.

In looking at vertical and horizontal relationships, your DOT EOC coordinates

horizontally – on the same level – as other State agencies, and

vertically with the State EOC. Coordination between ESF 1, Transportation representatives

can be vertical – up to the RRCC and NRCC, down to the local government

EOC, or horizontal – to the JFO Operations Section ESF 1, Transportation

representative.

slide 44

| Task | Local ESF 1 | State ESF 1 | JFO ESF 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESF 1 Representative | County Highway Department | State DOT | US DOT Regional Transportation Representative (RETREP) |

| Senior Transportation Representative | Superintendent of Highways or County Engineer | Secretary of State DOT, or his/her designee | US DOT Regional Transportation Coordinator (SES Level) (RET CO) |

| Evacuation of General Population | Establishes feeder routes to collection points | Provides resources as needed | Coordinates for air, rail, or bus transportation |

Clearing Debris |

Clears county and other local roads | Clears State roads; provides resources to counties | Provides funding for contractor support |

| Establishing Detours | For county and other local roads | For State roads | Provides supplemental transportation support if needed |

| Recovery Activities | Identify priority projects for recovery funding | Collate projects for identification as candidates for Public Assistance Funds | Provides State and local infrastructure personnel with PA Program guidance at meetings |

| Preparedness Activities | Coordinates with appropriate level Emergency Management Agency: conducts planning, training, exercise activity | Coordinates with appropriate level Emergency Management Agency: conducts planning, training, exercise activity | Coordinates with appropriate level Emergency Management Agency: conducts planning, training, exercise activity |

Slide Notes:

DOT Presence in EOCs

Your state will have an EOC that is managed by the State Emergency Management Agency. The purpose is to coordinate for and deploy state resources to support local governments. The EOC will also coordinate with other states and with the Federal government for resources. There will be personnel from each state agency in the Operations Section. The State DOT will provide one (1) or more people as representatives of ESF 1, Transportation.

The State DOT will most likely also establish an EOC. Your DOT’s EOC

will manage DOT resources deployed in support of local government response operations.

Local governments establish EOCs in which the County Highway Department may

be the ESF 1, Transportation representative.

slide 45

Slide Notes:

Provision of Resources

Earlier it was mentioned that resources should be obtained at the lowest level possible. There are two (2) more terms to consider:

Mutual Aid is an agreement between local governments and agencies to provide resources during an incident response. The best known of this type of assistance is when a fire department from a neighboring town assists a nearby department battling a large fire.

EMAC is a formal agreement managed by the National Emergency Management Association (NEMA) that facilitates sharing resources between states. During the response to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, many states sent resources to Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas. EMAC was the conduit through which these resources were coordinated.

During planning at the local and state level, resources provided by mutual aid and EMAC agreements must be included as available prior to requesting additional capability from the Federal government.

slide 46

Slide Notes:

Expectations

What can be expected of a State DOT? Expectations come from several arenas:

Agencies and organizations that are successful at responding to emergencies and disasters – and meeting expectations – have several traits in common. They all have a solid understanding of the need for being prepared to execute their emergency responsibilities. They all have at some level:

Advocating for a formal emergency management (EM) program sets the idea in the minds of all your employees that emergency preparedness, response, and recovery are important to the organization – and to the state.

What might an emergency management program look like?

slide 47

Slide Notes:

Organizational Constructs

One way to organize your emergency management program is around six (6) functional areas.

slide 48

Slide Notes:

Factors Affecting an Emergency Management Program

The decision on the organizational look, number of personnel and level of decentralization of your emergency management program will depend on several factors:

Optimally, you should strive to have individual elements; if that is not feasible, you may need to combine elements.

Centralization or Decentralization

Will your program be centralized or decentralized? A centralized emergency management program retains both policy and implementation responsibilities at the State DOT headquarters. A decentralized program retains policy and oversight, but allows implementation to occur at the regional or district level. The decision depends on the factors discussed above. However, the number of threats and the size of the state will more than likely be overarching factors.

Program Leadership

It is not recommended that program responsibilities be assigned to an existing

employee as an additional duty. Emergency management functions are fulltime

functions.

Optimally, the responsibility of preparing the State DOT to respond to incidents

and manage the response should be the only duty of the Program Manager. Recruiting

and hiring an experienced emergency manager to lead the program is one option.

Hiring a less experienced individual will require a lengthy period of training

and self study for a person to become familiar with concepts and procedures

that will create full effectiveness. Lastly, the person’s title and job

description should clearly reflect the duties and responsibilities assigned.

The best title is the most simple – Agency Emergency Manager responsible

for preparing the agency to respond to and recover from emergencies and disasters.

slide 49

Slide Notes:

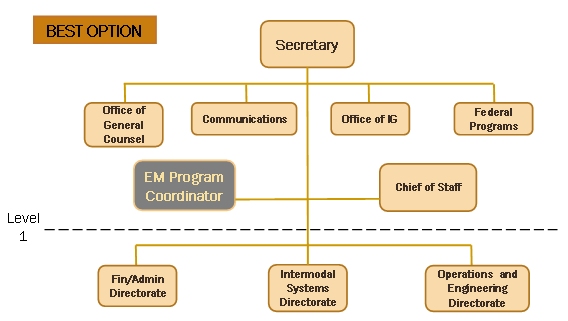

Emergency Management Placement

The next several pages show some options for the emergency management function in an organization and some benefits or disadvantages of each.

Based upon input from several State DOT representatives, the primary issues in locating the office are ensuring the emergency manager has the freedom of 24x7 contact with the top leaders of the agency and the perception of agency personnel regarding the importance of the emergency management function.

When deciding where to place the emergency management program on the State

DOT organization chart, think about how it is to be perceived. If you want everyone

to pay attention and work cohesively to build a top-notch response capability,

place it close to the most senior leader. The more distant it is from the top,

the less people will tend to notice and make the effort necessary to comply

with training and exercise requirements.

The bottom line is this: The State DOT emergency management program

will only be as viable as the attention and recognition it receives from senior

leadership.

slide 50

Slide Notes:

Best Option

This option places the Emergency Manager in position of advisor to the Secretary, thus ensuring all directorate heads will pay attention. This is the highest positioning possible.

Benefits:

slide 51

Slide Notes:

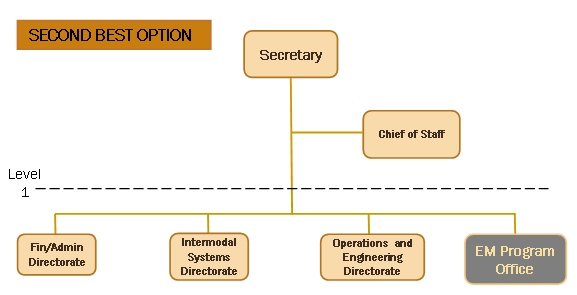

Second Best Option

Establish as separate office reporting to the Secretary, one step below the Secretary, on same line as directorate heads. This option has the many of the same benefits as the previous option.

Benefits:

An option:

slide 52

Slide Notes:

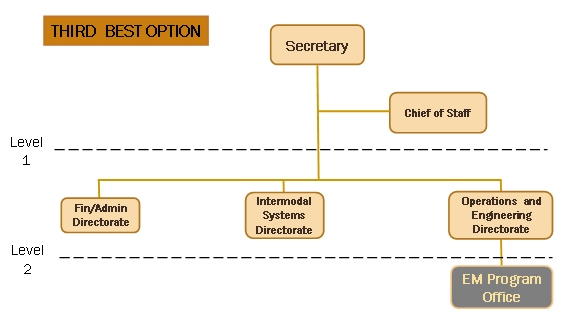

Third Best Option

Two levels below the Secretary, reporting to a directorate head.

While this option retains some benefits from the Best and Second Best, it starts to increase the distance between the Secretary and the program office, and reduces the chance for easy access and ability to communicate directly with the Secretary.

Cons:

Benefit:

slide 53

Slide Notes:

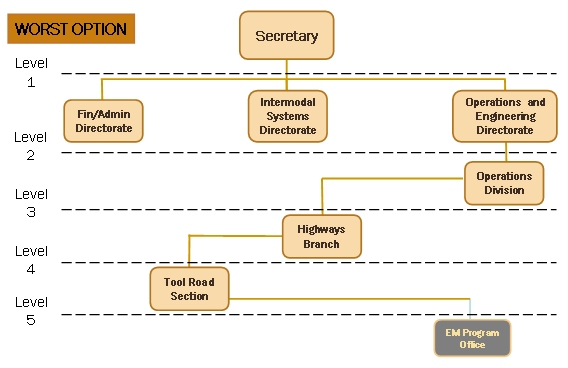

Worst Option

Several levels below the Secretary – buried as a subsection of a section of a branch of a division of a directorate

This option has many cons – and no pros.

slide 54

Slide Notes:

Leadership

It is necessary to say a few words about leadership and emergency management.

slide 55

Slide Notes:

Leadership

slide 56

Slide Notes:

Summary

To learn more and conduct additional research, some references are provided

on the next slide. If you have comments or questions about this briefing, contact

webmaster@dot.gov.

slide 57

Slide Notes:

These are on-line reference sources. You can also contact your State DOT Emergency Coordinator who can give you DOT-specific information. When you start talking, your interest may well be interpreted as a desire to work more closely in the area of Emergency Management and that it is important to you.