U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

|

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-06-095

Date: May 2006 |

This chapter brings together, as a single process, the concept of corridorwide planning, the use of a logical framework for strategy development, and CFA solution deployment from various perspectives. Relevant, cost effective technologies for a successful CFA operational deployment are assumed as part of the perspective solutions, but CFA supporting technologies and ITS systems are discussed at greater length in chapter 5. The four primary opportunities for coordinated operations identified in chapter 1 include:

Any one or several of the four areas may serve as the launch point for corridor focus and the source generating scenarios and solutions. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to applying the CFA process to each of these four areas. Methodological repetition is to be expected as each category employs the same corridor planning, framework, and enhancing technologies. The backbone of the process is the 11-step CFA framework introduced in chapter 2 (figure 6) and described in more detail throughout chapter 3. This iterative process applies to each category and results in a separate set of action scenarios and strategies.

CFA operations is a mindset. This handbook through chapter 4 has developed that mindset into a process that integrates operating systems and is enhanced by ITS related technologies. This chapter will relate the CFA process specifically to work zones, special events, incident management, and day-to-day/recurring operations. The basic concepts and technologies used for traffic management and incident management in the context of those systems have been covered extensively in many different texts. The same applies to work zone safety and motorist protection during highway reconstruction. Even special event planning has been thoroughly addressed more recently. Any one of the four areas of traffic management can serve as the starting point for developing a CFA approach to regional operations depending on the primary concerns and needs of a particular region. By presenting the CFA process from each perspective, it is hoped that the reader will recognize not only the different perspective but the essential similarity of the CFA mindset, technologies, and shared responsibilities.

The basics of traffic incident management are well known. There is significant guidance on the subject of incident management including Framework for Developing Incident Management Systems,(17) Traffic Incident Management Handbook,(18) Regional Traffic Incident Management Programs—Implementation Guide, (19) and the Freeway Management and Operations Handbook.(20) These materials provide many of the details associated with traffic incident management.

|

The key is in the expansion of the scope of incident management from a single agency to an entire corridor. |

Expanding incident management processes to corridors is the goal of CFA operations. While there is no specific formula for the successful development of a coordinated traffic incident management plan, the key is in the expansion of the scope of incident management from a single agency or group of agencies acting in relative isolation to a corridor-level approach. Coordinated operations puts the available operational elements together in an integrated package that focuses on maximum system performance from the users' perspective.

While it is possible to plan response scenarios for a variety of incident types and locations, it is not possible to plan when and where they will occur. The process is incident-driven rather than planned-for as in the other three categories. This significantly different aspect of incident management warrants more intensive scrutiny. The critical difference is planned events versus unplanned incidents. Corridor incident management, while requiring the same CFA process as the other opportunities for coordination, is treated differently from a technology enhancement point of view. The primary issues in dealing with corridor incident management are incident detection and the need for rapid response. The prompt detection of an incident, the determination of its impact on the affected facility and other roadways corridorwide, and the execution of a quick, effective response are essential.

While most traffic incidents impact little more than the travel route upon which they occur, more significant incidents, both traffic related and otherwise, can have corridorwide travel implications.

|

CFA operations are most beneficial under conditions of significant supply variations, such as incidents. |

The impact of major traffic incidents on the movement of traffic within a corridor can be dramatic, causing delays and congestion that overflows onto arterial streets and ramps and even increasing the likelihood of additional crashes. The purpose of this section is to reshape the issue of incident management coordination with a view toward providing a corridorwide perspective on the problem. At the conclusion of this chapter, readers will have an understanding of how to expand their approach to traffic incident management coordination from a single project focus to a corridorwide management perspective.

Problem identification is the essential first step that sets forth the rationale for exploring alternative courses to reduce the magnitude of a problem. Without a clearly defined problem, it is impossible to implement a solution that effectively alleviates the basic malfunction of the system. The problem definition step also allows the various stakeholders to reach consensus on something they all believe constitutes a problem worthy of joint action. Three issues are especially important in identifying problems that can be solved by coordinated incident management:

|

One of the most challenging issues to be resolved among the jurisdictions is the sudden increase of traffic in the surface street system due to diversion from the freeway as a result of an incident. |

As the frequency, duration, and impact of incidents increase, corridor incident management becomes more desirable to reduce delay and increase safety. Typical problems include increased congestion on alternative routes or unnecessary delay when alternative routes are available but not effectively utilized.

Incidents will often cause traffic to be diverted off the affected roadway to parallel and other alternate routes. If these alternative routes are not operated effectively for the incident-induced traffic, delays will occur to both diverting and nondiverting traffic.

The diversion may take place based on motorist information on the incident route or by the actions of individual motorists acting on what they believe to be in their best interests. The diversion point and route may lie outside of the jurisdiction experiencing the incident. To properly divert traffic to the roadways best able to handle the alternate volume, multiple agencies may need to coordinate their efforts. What is best for the mobility and the region as a whole may not be realized when diversions take place based on the decisions of individual drivers in response to general incident information or the lack of information.

In assessing current incident response practices from a corridor perspective, the following questions may be helpful in identifying problems that are amenable to coordinated incident management:(19)

The three basic principles of developing institutional relationships were presented in chapter 3. They are:

Incident management is an area that involves multiple agencies and disciplines, and that must be executed in real time. It therefore requires the clear delineation of roles and responsibilities, which can only be accomplished if an appropriate structure is developed to sustain the effort. The type of structure will depend on the local circumstances and, if possible, should build off existing relationships and interactions.

A unique aspect of incident management is the diverse group of individuals or agencies involved in it. The complexity of this involvement grows in corridor incident management because both the number of agencies engaged and the coordination issues among them increase significantly. The following are the types of individuals and agencies commonly involved in incident management:

|

Take advantage of attention focused on major events (e.g., international sporting events, weather events, earthquake) to help organize and build support for a formal incident management program. |

These are potential stakeholders in a corridorwide incident management program. To mobilize them into an effective coordinated incident management program requires a concerted effort to bring them together in new ways that help them perceive the benefits of corridorwide coordination.

It is necessary to have in place some degree of local incident management before initiating corridorwide coordination.(21)When no incident management program exists, the first step would be to develop a local program. If one agency or jurisdiction has an incident management program, start from that point and identify a broader group of stakeholders and build either new or expanded relationships that will benefit corridorwide coordination.

Another challenge is the identification of champions for expanding incident management to a corridor-level program. The champions' support is necessary to secure an initial commitment of resources in the form of staff and funding to begin the program development process.

To achieve the desired outcome, it is necessary to consider the legal and policy environment in which coordinated incident management is carried out. Four questions that may be helpful in determining this environment include:(19)

|

Having a neutral meeting space and staff are important for creating an equal playing field and enhancing trust among participants; but meetings alone are not enough. At the Greater Houston Transportation and Emergency Management Center (TranStar), physical co-location of multiple organizations, working side by side on a daily basis, established trust and created an understanding among the agencies of each other's activities, needs, and resources that would not be possible from meetings alone. |

Perhaps the best example of an organization initially formed to address incident management problems across jurisdictions is TRANSCOM, as described in section 3.4.(22) A series of debilitating incidents in 1986 caused problems on routes adjacent to the incident and led to the recognition of the interdependence of facilities and the establishment of TRANSCOM. Here, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey operated as the champion of the effort, providing leadership and seed funding. Since then, the organization has evolved and taken on a broader role in regional traffic management coordination.

The goals for corridor incident management are established before working on the detailed strategies for the corridor incident management program. This allows the partners to define broadly what they are willing to do before defining where and how they will do it. By starting with broad goals, the partners can define what aspects of corridor incident management they believe they can undertake. This is an important step because not all parties may see goals the same way. It is easier to understand conflicts at the goal level because they are general in nature.

For example, one goal might be:

To mitigate the corridor impact of major incidents on travelers by efficiently using freeway and surface street capacity during major incidents.

A broad goal such as this provides an opportunity for stakeholders to express differences. The goal suggests there are opportunities for improvement in incident response on both the arterial and the freeway system and that corridorwide action should be limited to major incidents, leaving lesser events to the individual agencies. If the arterial management agency is opposed to using arterials during incidents, it will become apparent during the drafting of a goal. At this point, however, it is not necessary to determine whether there are specific areas for which use of alternative routes is unacceptable, just whether the concept is supported in principle.

The next level of detail is objectives. Specific objectives might include:

These objectives help shape expectations of what is and is not reasonable from the perspectives of the partners. In formulating goals and objectives, the following corridor-based questions should be considered:

Typical incident response performance measures (generally measured in minutes) to be used for incident management include:

It is also possible to estimate reductions in delays based on the frequency, location, and duration of incidents. However, this requires more extensive analysis than would be typically undertaken.

Corridor incident management is not significantly different from agency incident management. However, in developing a corridor program, the coordinated response may be limited to more significant incidents. It is also useful to understand that excess capacity is more likely to occur during off-peak conditions. For example, a major truck accident at night may be more effectively addressed by an alternative route because the volume of affected traffic and the volume of traffic on alternative routes are likely to be less.

The corridor concept of operations is a formal document that provides a high-level, user-oriented view of operations in a specific corridor. It is developed in part to help communicate this view to the other stakeholders and to solicit their feedback. The corridor concept of operations provides a description of the current system, operating practices and policies, and existing capabilities. It lays out the program concept, explains how the corridor system is expected to work once it is in operation, and identifies the responsibilities of the various stakeholders for making this happen. The goals, objectives, and performance measures of a proposed operation are also documented. The process of developing a concept of operations for a corridor should involve all stakeholders and serve to build consensus in defining the goals and objectives; to provide a description of how functions are currently performed, thereby supporting resource planning; and to identify the interactions between organizations.

The basis of the corridor incident management concept of operations is the development of high-level problematic issues, which warrant corridor-level incident response. These issues are developed from the defined problems identified in the first step in the framework. Those problems that are identified and whose mitigation is consistent with the corridor goals and objectives would be candidates for mitigation. Those problems that merit mitigation would be developed into high-level problematic issue statements.

Problematic issues represent the initiating event for mitigation of the effects of incidents. At the concept of operations stage, problematic issues are high-level and do not focus on specific locations. One such issue would be a major incident on a freeway that would activate diversion plans involving traveler information, revised traffic signal control, and the initiation of a coordinated agency response.

At this stage, the cooperating agencies answer the questions of what (not how) they would be willing to do in the corridor in regard to coordinated operations in response to an incident. General strategies would include:

For example, a high-level problematic issue might be an incident on a busy parallel arterial street. The general strategy might be to use existing freeway DMSs to alert freeway drivers to the incident so they may choose to stay on the freeway and/or seek an alternative route. Another general strategy might be to provide special arterial signal timing when major incidents occur on the freeway.

The development of a concept of operations will allow the participating agencies to agree on what they wish to accomplish and to lay the framework for how that will be done. For example, does the traveler information only describe the nature of the problem or does it provide recommended courses of action? This is an example of an issue the agencies have to work out before moving to the more detailed level of discussion. This step sets the general ground rules for coordinated response.

As part of the development of a concept of operations, consider the following points:

|

The key to successful concept of operations development is remembering that this step involves the "who, what, when and where" of incident management. |

As discussed more fully in section 3.6, the concept of operations document that results from this development process could include sections on the following topics:

The concept of operations defines the general scenarios that will be used to address the identified problems and is consistent with the corridor goals and objectives. Activation criteria and the types of response, specific scenarios, and strategies will ultimately be worked out in the design and development step. The key to successful concept of operations development is remembering that this step involves the "who, what, when and where" of incident management. The corridor plan will determine how these details will be implemented.

Once the concept of operations is agreed to, scenarios and potential strategies need to be refined. Specific questions need to be addressed, such as:

The concept of operations scenarios need to be developed for specific locations where corridor incident management would be implemented. For example, freeway and arterial segments where the frequency of incidents causes significant corridorwide congestion need to be identified. This identification process is done best with the involvement of all the corridor partners to incorporate the widest possible perspective of the problem and to develop a sense of engagement among the implementing partners.

The process of selecting scenarios is somewhat iterative with the strategies to be implemented. For example, if strategies include alternative routes, the scenarios need to reflect the logical points at which diversions might be implemented.

Strategies are specific actions to mitigate one of the scenarios associated with a corridor incident. Several strategies may be required to achieve the desired improvement in system performance. The strategies may also vary by the severity of the incident.

Individual agencies might consider the following examples of candidate strategies to achieve improved corridor operation:

Shared resources represent one of the potential major benefits of coordinated operations, especially during major incidents. Most agencies cannot provide sufficient staff and resources to deal with unusually large incidents; however, through shared resources, collaborating agencies can make available many more resources than they could individually provide. Since a major incident often has substantial spillover effect, shared resources are a win-win proposition for all stakeholders involved.

At this point the strategies are still general ideas of how agencies can work together, but are being focused on specific segments of roadway. In the next step, the strategies are analyzed in more detail to identify practical considerations as well as costs and potential benefits. The current objective is to consider taking traditional strategies beyond agency boundaries to improve corridor operation. What is possible technically and what is possible practically? The answers will depend on many local factors. The important point is to begin the dialogue among partners to determine what is possible.

The process of selecting specific strategies is an iterative process involving the stakeholders in assessing both the costs and the benefits of the strategies and the various agencies' ability to implement them. A strategy may be perceived to be positive initially, but a more detailed analysis may show it to be counterproductive. A strategy may be technically feasible, but beyond the resources available or inconsistent with other community values.

As the stakeholder group considers specific strategies, the following issues will ultimately come under discussion:

Each of the agencies must be comfortable with the strategies and be capable of implementation. The degree of sophistication of the strategies will depend on the current capabilities of the agencies and the degree to which the agencies desire to invest in technology and/or staffing to achieve better operations.

The evaluation of strategies may vary from qualitative to quantitative methods. Integrated traveler information may be evaluated qualitatively because the impacts are difficult to assess and the potential for problems minimal. A strategy to divert traffic from the freeway to a parallel arterial should involve adequate quantitative analysis to avoid creating a larger problem than the one being resolved. In some cases, more sophisticated tools such as simulation models may be required to determine the feasibility and appropriateness of a strategy.

The process of selection may be simple or complex depending upon the nature of the problem being addressed and the need for quantification of benefits. In some cases, the strategies may be more dependent upon consensus among the stakeholders than analytical analysis.

The following are some possible items to consider before diverting traffic either from a freeway to an arterial, or from an arterial to a freeway:

In planning the operational strategies to be used during incidents, there are questions which should be considered, such as:

Is the incident on the freeway or the arterial street?

|

It may be preferable for safety reasons not to designate roads containing schools, hospitals, parks, or residential areas as alternative routes as they may have speed restrictions or speed control devices installed (e.g., speed humps). |

There are a number of differences depending upon where the incident occurs. If the incident is on the freeway and traffic is diverted to the arterial street, the local agency operating the arterial needs to be aware of the diversion and should take steps, such as a survey of the arterial street, to assure traffic is hindered as little as possible. Adjustments to signal timing, removal of temporary roadwork, and other steps can also facilitate traffic diversion. If the incident takes place on the arterial street and traffic is diverted to the freeway, there are probably fewer considerations, but notifications still need to be made and adjustments, such as changes to ramp metering, may have to take place.

What time of day and on which day of the week did the incident take place?

An incident occurring on a weekend will have a different response from one taking place on a weekday. For example, schools along the alternate route will not be open on Saturdays and Sundays, but traffic to a shopping district will be heavier. The time of day will also have an impact: incidents during peak periods will cause even greater congestion than is typically experienced. Available resources, especially staffing, will vary depending upon the time of the incident.

What capacity loss does the incident present?

An incident which occurs in the early morning hours and shuts down one lane of a three-lane highway will present a minor loss of capacity and it may not be necessary to implement any coordination between the freeway and arterial street operators beyond notifications. At the other extreme, a full closure of either the arterial street or the freeway may force a diversion between the roadways.

What is the cost of various coordination efforts?

Most actions, beyond notifications, carry some cost to the agencies responsible for carrying them out. For example, if a city must deploy police officers to direct traffic manually at diversion points or through intersections, there is a significant cost for supplying that labor. Issues of who pays for what should be worked out ahead of time so that concerns about cost do not delay implementation of plans during an incident.

What resources are available?

Knowing ahead of time what resources can be used allows the agencies to improve coordination of their efforts and to determine what level of response is appropriate. Permanent DMSs can be easily adjusted with messages displayed even for incidents of short duration. On the other hand, if portable signs need to be deployed, agency personnel must consider whether the time and effort to retrieve the signs, transport them to the location, and program messages is worth the effort given the expected duration of the incident.

Upon completion of this step of the process, all stakeholders should have a detailed understanding of what strategies are feasible and supported by the corridor agencies. The next step is to package all of the strategies in a corridor implementation plan, which is a formal document that can be used to secure the funding necessary to advance the program to design.

The corridor implementation plan is the final product of the decisionmaking segment of the CFA operations framework. It documents all the steps previously undertaken with sufficient detail to see the project or projects developed for improved corridor operations through implementation.

The corridor implementation plan would include the following elements:

Multiple scenarios are developed for the package of operations plans, which forms the basis of the corridor implementation plan. To implement the operations plans requires an assessment of the resources required for the implementation phase of the framework (design, deployment/ implementation, and operations and maintenance). The corridor implementation plan compiles the operations plans and the necessary supporting resources in a complete package that can be used to secure the funding necessary for design, implementation, and operation and maintenance. The plan is also needed to provide documentation for securing the institutional consensus necessary to proceed.

In summary, after the concept of operations, the corridor implementation plan is the second major milestone. It is a formal document that contains sufficient detail to move the plan to the next step, which is design and development, and may contain a number of projects, especially if it is necessary to fund and construct the implementation over a long timeframe. The plan would also indicate priorities among projects, potential funding sources, and cost allocations.

The design and development step initiates the implementation phase of the framework. The design transforms corridor implementation plan concepts into practice and covers many details, including the construction plans necessary to build the supporting infrastructure and the detailed procedures and supporting agreements necessary to operate and maintain the operations plans.

The issues to be addressed in the design phase include:

|

When more than one agency is involved in the funding and development of a system, a memorandum of understanding (MOU) may be necessary to dictate which agencies are responsible for the maintenance of each component of the system. |

The important aspect of the design phase is that it requires selection of the technologies that are necessary to support the operations plans included in the corridor implementation plan. The specifics will be highly individualized because of the variety of ways in which individual agencies work and the amount of sharing of information and control that is acceptable. Under a loosely integrated system, control system changes could be implemented by a telephone call requesting a special timing plan. Under a closely integrated system, an agency with a 24/7 operation might be able to implement preplanned strategies when the agency owning the equipment is not staffed for operation.

The design phase also calls for development of specific details of the strategies to be

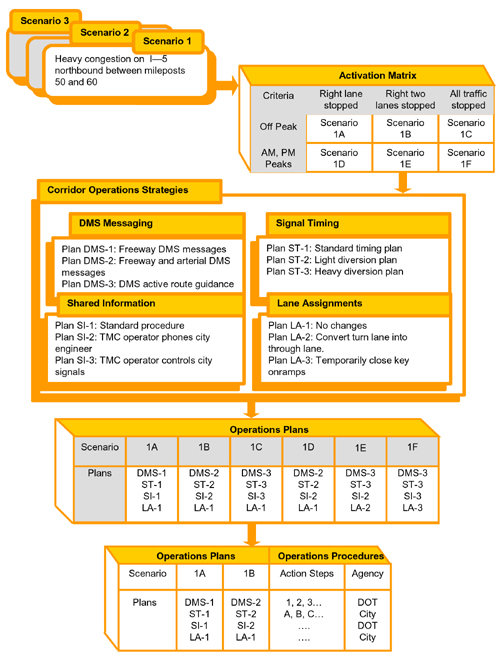

implemented, similar to those noted in figure 16. This would include details like loading specific messages onto DMSs and creating signal timing plans for coordinated diversion routes. This is where development of plans and procedures are made for each strategy that was selected earlier. These plans are then packaged into a separate operations plan for each scenario. Specific procedures are created for each plan to define roles and responsibilities. See chapter 3 and figure 13 for more information.

Figure 16. Chart. Example of operations plans and procedures for incident management scenarios.

The deployment phase includes activities in preparation for implementation and the various actions necessary to implement the system designed in the previous step.

Some of the following activities may be required prior to implementation:

The implementation process may involve both people and infrastructure. There may be new staff that needs to be hired and trained. As the complexity of the project increases, phasing and timing of the various elements needs careful consideration so that the system components can be deployed and tested in a timely fashion.

In the development of most CFA deployments, it is anticipated that the majority of activities will involve integration and enhancements of disparate monitoring and control systems. Given the assumption of integration, consideration should be given to adopting ITS standards whenever possible in the deployment process.

Overlooking operations and maintenance often results in serious negative consequences. Without ongoing support for a project, its potential cannot be achieved; therefore, operation and maintenance must become a part of the routine operation of the agencies. To achieve this, it may be necessary to designate an individual to handle the coordination of the unique requirements of shared operations and management of the corridor. Given the irregular frequency of incidents, there may be substantial cost savings in integrating incident management responsibility.

|

Assigning full responsibility and authority to the program manager usually facilitates success of a large technical project. |

Continuous improvement should be well integrated into the overall process. The performance monitoring system should provide feedback on both the success of individual operations plans and the need for other actions. In addition, regular meetings facilitate ongoing communications. These meetings would address both experiences and lessons learned from coordinated operations and refine existing operations. An annual meeting to review the program more broadly regarding overall operations plans would also be desirable. This is particularly critical for corridor incident management as many of the response strategies are difficut to develop. For example, diversion volume and corresponding signal timings must first be estimated based solely on projected demands. Once the system has been in actual operations, these operations plans can be calibrated and upgraded.

It is often the case that a work zone has a ripple effect on transportation within a corridor, particularly when they lie within high-traffic areas or areas that are subject to extreme a.m. or p.m. peak movements. The purpose of this section is to recast the issue of work zone management in the context of the coordinated freeways and arterials framework. At the conclusion of this section, the reader will have an understanding of how to expand their approach to work zone coordination from a single project focus to a corridorwide management perspective.

A view that focuses on maximum system performance from the users' perspective by minimizing the overall effects of the work zone is essential. |

The impacts of work zones are not always restricted to the work zone itself. These impacts may be felt in the area in advance of the work zone, in other roadway corridors, within the regional transportation network, and on other modes of transportation. It is important to understand that the types of strategies deployed may change based on the duration of the operation.

Expanding work zone management processes to corridors is the goal of CFA operations. There is no magic formula for development of coordinated work zone management; the key is to expand the scope of work zone management from a single project focus to a corridor management view. A view that focuses on maximum system performance from the users' perspective by minimizing the overall effects of the work zone is essential.

The following factors help define the work zone problems that should be addressed:

Type and duration of work zones can have a potentially significant corridor impact. However, it is also important to understand the potential impact of multiple work zones on each other. Often individual work zone projects would have modest impact on travelers if it were not for another work zone that either compounds the principal delay or affects alternative routes.

The type and duration of work zones affects both the extent of the potential problems and the potential remedies. The longer and larger the work zone, the more likely that mitigation efforts will be cost effective. The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices classifies work zone operations as follows:(23)

The important point to derive is that the impact of work zones can vary from large projects that impact an entire city to smaller projects to a daily pothole patching crew on the local freeway. This section focuses on work zone projects that impact both freeway and arterial operations.

In assessing current work zone practices from a corridor perspective, the following questions may be helpful in identifying problems that are amenable to coordinated work zone management:

The basic principles of developing institutional relationships were presented in chapter 3. Those principles are:

Work zone management is an area that involves multiple agencies and disciplines and therefore requires the clear delineation of roles and responsibilities. An appropriate structure must be developed to sustain the effort. The type of structure depends on local circumstances and should build, if possible, on existing relationships using any of the structures described in chapter 3.

To advance a large project from inception through implementation may require the organization of executive, steering, and operation committees that will need to be informed throughout the various stages of the project.

The key stakeholders that need to be involved in work zone operations fall into the following categories:

To mobilize these individuals and agencies into an effective CFA work zone management program, a concerted effort is required to bring them together in new ways to realize the benefits of corridorwide coordination.

It is necessary to have in place some degree of work zone management to implement a coordinated program. Agencies wishing to assess their work zone management practices may wish to take FHWA's Work Zone Mobility and Safety Self-Assessment Guide.(24) This tool allows agencies to judge their own programs' achievements and to identify areas for improvement.

If no work zone management program exists, the first step is develop a local program. Assuming at least one agency or jurisdiction has a work zone management program, the next step is to expand work zone management beyond traditional agency or jurisdictional boundaries. The process requires identification of a broader group of stakeholders and either building new relationships or expanding established relationships.

To achieve the desired outcome, it is necessary to consider the legal and policy environment in which coordinated work zone management is carried out. Questions that may be helpful in determining this environment include:

The remainder of this section highlights the unique issues of CFA management, which extends the principle of local work zone management to a larger venue. The first challenge is to identify champions for expanding work zone management to a corridor-level program. The champions' support is necessary to secure an initial commitment of resources (staff and funding) to begin the program development process. It ensure success, champions must emerge or be identified as part of the coalition-building process. The champions guide the project from inception to completion and help navigate through the institutional challenges.

Goals, objectives, and performance measures should be developed based on the consensus of the stakeholders to establish a unified foundation for developing CFA operations during work zones. CFA operations specifically for work zones should address the following key goals:

It can sometimes be difficult to reach a balance between these goals. A full roadway closure would achieve four of the five goals, but would generally not be considered because of the inconvenience to the public. However, even full roadway closures are now being considered. An example of implementation of a full lane closure project and can be found at: http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/wz/workshops/accessible/LaRue_paper.htm.

In addition, special considerations to minimize the impacts of work zone operations on response time by emergency management services needs to be addressed. Once the goals have been established, specific objectives can be defined to reflect the various perspectives of those impacted by work zone activity, such as the traveling public, work zone workers, and the responsible jurisdiction(s). Table 7 is an example of work zone objectives.

| Perspectives |

Work Zone Objectives |

|---|---|

Traveler |

Travel delay no greater than X percent. |

Workers |

No work zone-related fatalities or injuries. |

Jurisdiction |

Achieve crash rate no higher than exists without work zone. |

The determined goals and objectives will influence the work zone sequence and impact the types of strategies considered to improve the CFA. The most important performance measure from the traveler perspective is any delay that the work zone operation will have on their trip. While the public understands that delays are likely from a work zone operation, there is a limit to what will and will not be tolerated.

The development of goals and performance measurement for work zone operations is also an evolving area. Areas for potential goal setting and performance measure are:

Planning should address such issues as coordination across agencies, projects, and time, as well as a consideration of work zone implications throughout the project life cycle.

Mobility measures should include a consideration of impacts through the whole life cycle (before, during, and after a work zone) on all modes of transportation (multimodal) throughout the affected corridor (corridorwide). Mobility also addresses the availability of useful and reliable information to travelers and operating agencies and the use of ITS technology to measure performance, provide information, and manage traffic.

Safety measures will promote continuous review of work zone design and management, and the reduction of accidents and fatalities through efforts to maximize work zone safety management. In summary, the goals of an effective CFA work zone project would include maximum safety and minimum disruption to travelers. To achieve such goals, a broad view of the interactions of various decisions, especially those caused by a lack of coordination between agencies, must be considered.

The corridor concept of operations is a formal document that provides a high-level, user-oriented view of operations in a specific corridor. It is developed in part to help communicate this view to other stakeholders and to solicit their feedback. The corridor concept of operations provides a description of the current system, operating practices and policies, and existing capabilities. It lays out the program concept, explains how the corridor system is expected to work once it is in operation, and identifies the responsibilities of the various stakeholders for making this happen. The goals, objectives, and performance measures of a proposed operation are also documented. The process of developing a concept of operations for a corridor should involve all stakeholders and serve to build consensus in defining the goals and objectives; to provide a description of how functions are currently performed, thereby supporting resource planning; and to identify the interactions between organizations.

The formality of a concept of operations will depend on the nature of the work zone activity. Short-term work zones will not usually warrant a complex concept of operations. However, a generic concept of operations may be appropriate for walking through the issues and alternatives associated with short-term work zones. Guidance on best practices which can form the basis for developing a concept of operations may be found at: http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/wz/practices/best/Default.htm.

Long-term work zones associated with major construction or reconstruction projects requiring months or years to complete warrant the development of a more complex concept of operations. The operations plan provides a package of strategies associated with one or more specific scenarios.

In the case of minor work zone activities (e.g., mobile, short duration, or short-term stationary work zones as defined in section 4.4.1), providing traveler information, scheduling during off-peak hours, and coordinating work zones activities between agencies may be all that is necessary. The development of a corridor work zone Web site can be a simple means to achieving coordinated agency activities and dissemination of traveler information. More extensive work zone activities may necessitate more active traffic management and control as well as more extensive resource sharing.

At this stage, the cooperating agencies should address questions of what (not how) they are willing to do regarding coordination of work zone activities in the corridor. Perhaps the biggest opportunity for improvement of work zone operations is coordination between agencies at the planning stage of work zone projects. Avoiding projects that have overlapping impacts could substantially reduce traveler delay with a very modest investment in resources. Other general strategies to be considered include:

The development of a concept of operations allows the participating agencies to agree on what they wish to accomplish and to lay the framework for how it will be done. For example, are the agencies willing to discuss their schedules for construction projects? This is an issue agencies should resolve before moving to the more detailed level of discussion.

As part of the development of a concept of operations, consider the following points:

The concept of operations document could include the following sections:

In summary, the concept of operations defines the overall plan that addresses the goals and objectives of work zone management coordination, the high-level scenarios to be addressed, the activation criteria, and the type of response. The concept of operations phase of planning involves the "who, what, when, and where" of work zone management.

The concept of operations provided the high-level scenarios to be addressed and a general discussion of the types of strategies to be implemented to achieve agency support. Once the concept of operations is agreed to, the scenarios and potential strategies need to be refined. Specifically, what segments of highway and under what conditions are strategies to be implemented? What are the potential strategies that might be implemented to mitigate each work zone scenario? The concept of operations scenarios need to be developed into specific locations where work zones would be implemented. For major construction projects, the location would be project specific. For short-term work zones, the scenarios would be more generic, focusing on freeway or arterial sections having similar strategies regardless of a specific work zone location.

The process of selecting scenarios is conceptually linked to the strategies selected for implementation. For example, if strategies include alternative routes, the scenarios need to reflect the logical points at which diversions might be implemented.

Strategies are specific actions to mitigate one of the scenarios associated with a work zone. Several strategies may be required to achieve the desired improvement in system performance and would vary by the duration and impact of the work zone.

Specific examples of candidate strategies that individual agencies might consider to achieve improved corridor operation include:

At this point, the strategies are still high-level, general ideas of how agencies can work together but focused on specific segments of roadway. In the next step, the strategies are analyzed in more detail to understand practical issues such as costs and potential benefits. The current objective is to consider taking traditional strategies beyond agency boundaries to improve corridor operation. What is possible technically, and what is possible practically? The answers will depend on many local factors. The important point is to begin the dialogue among partners to determine what is possible.

The opportunities for corridor work zone management coordination need to reflect the unique characteristics of incidents. At the corridor level, the two issues that need to be considered are timeframe and significance of benefits relative to the effort.

Short-duration work zones coordination, unless having major capacity reductions, may warrant only the dissemination of traveler information. A coordinated traveler information program can easily be implemented at virtually no additional cost or effort within an agency-specific program.

As the severity (amount of capacity reduction) and duration of a work zone increases, the potential benefits of more aggressive strategies increase.

An example of some operations strategies that might be applied to work zones are shown in table 8. Because work zones vary in duration, it is important to understand the impact of time on the deployment of specific strategies.

| Category |

Example Strategies |

|---|---|

Traffic Management and Control |

|

Freeway management |

Ramp closures. |

Arterial management |

Access and turn restrictions. |

Traveler Information |

|

En route traveler information |

DMS (temporary and permanent). |

Pretrip traveler information |

Internet. |

|

Shared Information and Resources |

|

| Incident response |

Motorist service patrols. |

| Traffic surveillance |

CCTV systems. |

| Information systems |

Incident reports. |

Shared resources represent one of the potential major benefits of coordinated operations, especially during major construction projects. Through shared resources, the collaborating agencies can make available more information then they can individually provide. Since a major work zone is often has substantial spillover effect, shared resources are a win-win proposition.

The process of selecting the specific strategies is an iterative process involving the partners in assessing both the costs and the benefits of the strategies and the various agencies ability to implement the strategies. A strategy may be perceived to be positive, but a more detailed analysis may show it to be counterproductive. A strategy may be technically feasible, but not selected because it is beyond the resources available, or possibly inconsistent with community values.

The following factors can be used to evaluate potential traveler information, traffic management and control, and shared information and resource strategies that can be used to be coordinate freeway/arterial roadways during work zone operations:

There are some analytic tools that can determine the impact of work zone operations on a roadway and therefore provide some indication on the volume of traffic that might need to be diverted to alternate routes or shifted to alternate modes. An example is QuickZone. Information on QuickZone can be found at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/research/tfhrc/its/quickzon.htm.

QuickZone is the first tool developed under the Strategic Work Zone Analysis Tools program. These tools are intended to be user-friendly software tools that assist those in the highway community with decisionmaking. QuickZone is a traffic impact analysis spreadsheet tool that can be used for work zone delay estimation. The purpose of QuickZone is to:

At this point in the process, there is a clear overlap between incident management and work zone operations response planning. There are similar, important review items to be considered prior to diverting traffic from a freeway to a surface street, including whether or not there are permit or utility operations that have been deployed without prior notice; the presence of schools, hospitals, or shopping centers on the alternate route; and the presence of major employment centers on the diversion route. Additional considerations include the question of whether temporary turning or parking restrictions are needed. If so, the question then arises as to whether it is possible to deploy manual resources to erect appropriate signing and/or implement such changes safely and in a timely manner. Additional discussion of strategy evaluation and selection considerations can be found in section 3.8.

While each jurisdiction may have individual characteristics, and it is preferable to have preplanned diversion routes, the following are some possible items to review before diverting traffic from a surface street to a freeway:

In planning the operations strategies to be used during work zones, there are questions which should be considered:

What is the cost of various coordination efforts?

Most actions, beyond notifications, carry some cost to the agencies responsible for carrying them out. For example, if a city must deploy police officers to manually direct traffic at diversion points or through intersections, there is a significant cost to supply that labor. Issues of who pays for what should be agreed to ahead of time.

What resources are available?

Knowing ahead of time what resources can be used allows the agencies to coordinate their efforts more effectively and to determine what level of response is appropriate. Permanent DMSs can be easily adjusted with messages displayed even for work zones of short duration. On the other hand, if portable signs need to be deployed, agency personnel must consider whether the time and effort to retrieve the signs, transport them to the location, and program messages is worth the effort given the expected duration of the work zone.

Upon completion of this step, all stakeholders should have a detailed understanding of what strategies are feasible and supported by the corridor agencies. The next step is to package all of the strategies in a corridor plan, which is the formal document, which can be used to secure the funding necessary to advance the program to design.

The corridor implementation plan is the final product of the decisionmaking component of the CFA operations framework. It documents all the steps previously undertaken with sufficient detail to take the project or projects developed for improved corridor operations to the implementation stage.

The corridor implementation plan is the second major product after the concept of operations. It contains sufficient detail to move to the design step and may contain a number of projects, especially if it is necessary to fund and construct the implementation over a long timeframe. The plan should also indicate priorities among projects, potential funding sources, and cost allocation.

A detailed discussion of the elements of the corridor implementation plan and a list of the issues and resources that need to be addressed during its development are in section 3.9 above.

Design and development is the first step in the implementation section of the framework. This is a significant step forward in that it transforms the corridor implementation plan concepts into projects that are able to be implemented. It covers many details of implementation including the necessary construction plans to build the supporting infrastructure and specifies detailed procedures and supporting agreements necessary to operate and maintain the operations plans. A detailed discussion of important elements of the design phase can be found in section 3.10 above.

The implementation of the design and development phase can be either separate from the work zone contractual package or incorporated as an early phase. Regardless, the important consideration in either case is the required leadtime to implement the strategies prior to the start of the work zone operations. In some states, design/build procurements are used to consolidate this step and deployment, the next step. The selection of technologies addresses the way the varying phases of construction will impact the use of ITS technologies.

Strategies may also vary by time of day, reflecting both the volume of traffic on the freeway and the conditions on adjacent arterials. Table 9 is an example of a corridor operations plan with activation criteria based on freeway capacity loss, duration of work zone, and the time of day. In this freeway example, letters represent the level of response, which are recommended based on three factors: the time of day the incident occurs, the expected duration of the incident, and the amount of capacity lost on the roadway experiencing the incident. The example shown is fairly complex and could be simplified based on reducing the number of time periods and the number of categories of duration.

| Freeway Capacity Loss |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of Day |

Duration |

Low |

Medium |

High |

All Day |

24 hours (h)/day |

N, T, A, M, D1 |

N, T, A, D1 |

N, T, A, M, D2 |

Weekday Daytime |

0-20 minutes (min) |

N |

N, T |

N, T, A |

Weekday |

0-20 min |

N |

N, T |

N, T |

Weekend Daytime |

0-20 min |

N |

N, T |

N, T, A |

Weekend |

0-20 min |

N |

N, T |

N, T |

N = notification is made to affected agencies. Notes: ·It is assumed that different governmental entities operate the surface street and freeway systems. ·A decisionmaking matrix is needed when a diversion to an alternate route is warranted that requires confirmation of available capacity and/or the absence of a planned or unplanned event on that route. · Traveler information systems can be portable or permanent DMSs, HAR, kiosks or Internet-based systems and also include media/traffic service notifications. | ||||

While strategies are funded and developed with the specific work zone operation in mind, where possible there should be some consideration to the continued use of these strategies beyond the work zone operation.

The deployment phase includes activities in preparation for implementation and the various steps necessary to implement the system designed in the previous step. A full discussion of the considerations required for implementation can be found in section 3.11.

Operations and maintenance is often overlooked with serious negative consequences. Within an agency, someone must be responsible for coordinating the operations and maintenance of any mitigation strategies. Where possible, the champion should encourage incorporating this activity into an existing TMC or operation. Other considerations in the operation and maintenance of work zone mitigation strategies are as follows:

Continuous improvement should be well integrated into the overall process. As stated in previous sections, the performance monitoring system should provide feedback on both the success of individual operations plans and the need for other actions. In addition, regular stakeholders meetings are an advantageous means of facilitating ongoing communications and exchanging stakeholder experiences with coordinated operations to refine existing operations.

The National Work Zone Safety Information Clearinghouse (http://wzsafety.tamu.edu/) is a reference tool on policies, practices and technologies that have been effectively used to manage work zone operations. This site is updated regularly and is an ongoing source of information.

A planned special event is a public activity or series of activities with a scheduled time and location that may increase or disrupt the normal flow of traffic on affected streets or highways.

As with work zones or traffic incidents, special events may also have a ripple effect on transportation within a corridor for many reasons. The unsuspecting traveler may encounter unexpected delays, and when alternative routes are not clearly conveyed to travelers, congestion and incidents are more likely to occur. The purpose of this section is to apply the CFA framework to planned special event management in a corridor. The benefits of taking a corridorwide view of special event coordination include maximizing system performance and effectively minimizing the overall effect of the special event on the transportation system within that corridor. At the conclusion of this section, readers will have an understanding of how to expand their approach to special event coordination from a single, local project focus to a corridorwide management perspective.

The impacts of special events may not always be restricted to the immediate event venue. The impacts may be felt on other roadway corridors, within the regional transportation network, or on other modes of transportation.

Expanding the special event coordination processes to corridors is the goal of CFA operations. While there is no single solution for development of special event coordination, the key to success is the expansion of the scope of special event coordination from a venue focus to a corridor management view. Special event coordination takes a corridor view that focuses on maximum system performance from the users' perspective by minimizing the overall effects of the special event.

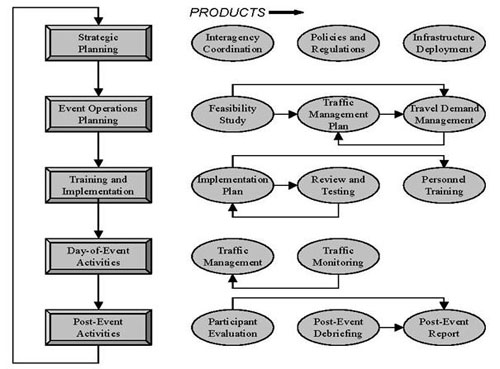

The guidance from Managing Travel for Planned Special Events provides many of the details for developing special event plans and procedures.(25)Figure 17 shows the recommended process for managing special events in Managing Travel for Planned Special Events. Many of the steps in figure 17 are similar to the 11-step CFA process detailed in this handbook. These similarities will be highlighted in the remainder of this section. Event operations planning, shown in figure 17, is similar to steps 1 (problem identification) through 6 (evaluation and selection of strategies) of the CFA process. Event operations planning involves developing: a feasibility study for the proposed planned special event; a traffic management plan to service event-generated auto, transit, and pedestrian traffic and to mitigate transportation impacts; and a travel demand management plan when forecasted traffic demand levels approach or exceed available roadway capacity.

Training and implementation, as shown in figure 17, is similar to the corridor implementation plan and design and development steps of the CFA process. Training and implementation starts with the development of an implementation plan ranging from a brief memorandum, and concludes with an event management manual. Stakeholders representing the event planning and traffic management teams interact through event simulation exercises that may consist of a tabletop exercise, an event walk-through, or a traffic management plan deployment during a smaller-scale event. These exercises assist participants in identifying potential traffic management plan deficiencies and, in addition, will allow traffic management team members to become familiar with decision criteria and contingency plan details.

Figure 17. Chart. Integration of planned special event management phases.(25)

Day-of-event activities, as shown in figure 17, are similar to the operations and maintenance step of the CFA process. Day-of-event activities focus on the implementation of the traffic management plan in addition to traffic monitoring. The traffic management team represents a distinct stakeholder group charged with executing the traffic management plan. Traffic monitoring provides traffic and incident management support in addition to performance evaluation data. Timely deployment of contingency plans developed during the event operations planning phase depends on the accurate collection and communication of real-time traffic data between traffic management team members.

Post-event activities, as shown in figure 17, are similar to the continuous improvement step of the CFA process. Post-event activities range from informal debriefings between agencies comprising the traffic management team to the development of a detailed evaluation report. Qualitative evaluation techniques include individual debriefings of traffic management team members, patron surveys, and public surveys. Quantitative evaluation techniques include performing an operational cost analysis and analyzing traffic data collected during the traffic monitoring process.

Planned special events include sporting events, concerts, festivals, and conventions occurring at permanent multi-use venues (e.g., arenas, stadiums, racetracks, fairgrounds, amphitheaters, convention centers, etc.). They also include less frequent public events such as parades, fireworks displays, bicycle races, sporting games, motorcycle rallies, seasonal festivals, and milestone celebrations at temporary venues. The term "planned special event" is used to describe these activities because of their known locations, scheduled times of occurrence, and associated operating characteristics. Emergencies, such as a severe weather event or other major catastrophe, represent special events that can induce extreme traffic demand under an evacuation condition. However, these events occur at random and with little or no advance warning, thus differing from planned special events.

Substantial technical material exists in the FHWA technical reference Managing Travel for Planned Special Events.(25) It presents and recommends various planning initiatives, operations strategies, and technology applications that satisfy the special customer requirements and stakeholder performance requirements driving planned special event travel management. This section summarizes that reference, highlighting the essential elements involved in managing traffic during planned special events. In addition, opportunities for CFA operations will be highlighted.

Because of the high visibility of such events, agencies naturally come together. In addition, because of their unique nature, day-to-day plans and procedures are, by definition, not applicable. The short duration of special events may also make agencies more willing to commit resources because it does not represent an ongoing commitment.

An appropriate institutional structure needs to be developed to sustain the effort. The type of structure will depend on the local circumstances and should build, if possible, on existing relationships, but the basic principles of developing institutional relationships remain the same: establish a structure, identify corridor stakeholders, and identify corridor champions.

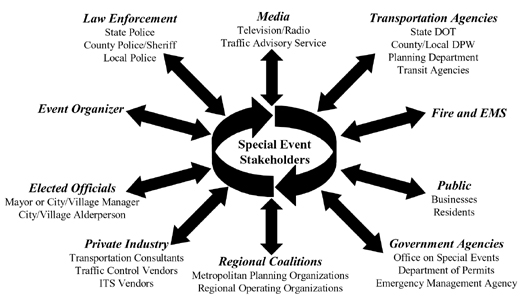

Figure 18 presents common stakeholders, representing various disciplines and jurisdictions that play an active role in managing travel for planned special events on a local and/or regional level. The balance of this section describes the potential roles and responsibilities of each identified stakeholder in addition to his or her coordination with other planned special events stakeholders.

Figure 18. Chart. Stakeholders who may be involved in planned special events. (25)

Law enforcement facilitates the safe and efficient flow of traffic during a planned special event through traffic control and enforcement. Agencies contribute to all phases of planned special events, particularly event-specific advance planning and traffic management. Local and county law enforcement having a traffic operations bureau may take responsibility for developing and executing a surface street traffic management plan. Other potential duties of law enforcement include approving local street closures, approving an event traffic flow plan, approving temporary traffic control deployment, escorting dignitaries to/from the event venue, and enforcing the requirements of a traffic operations agency.

Event organizers initiate the event operations planning phase by notifying stakeholders, through a written request to public agencies or the submission of an event permit application, and assembling an event planning team. The event organizer continually works to maintain interagency coordination to meet milestones in the advance planning process and ultimately gain stakeholder approval of the proposed transportation management plan. The event organizer may hire a private traffic engineering consultant to perform an event feasibility study and prepare a traffic management plan. The event organizer usually funds the deployment of equipment and

personnel resources, including reimbursement of public agency personnel costs required to mitigate traffic safety, mobility, and reliability impacts during the day-of-event. However, event organizers for major special events that occur on a regular basis may work together with transportation agencies, law enforcement, and elected officials during the strategic planning phase to develop strategies, including permanent installation of equipment for improved traffic monitoring and control and to better accommodate traffic and transit access to the venue.

Elected officials serve the overall community interest and often have a significant role on an administrative team. Local politicians can establish laws and regulations toward effecting improvements in planning and managing future planned special events. A local mayor or manager may create a special task group to assist event organizers and local agencies coordinate event-planning activities. Local district politicians may advise an event planning team on alternatives to minimize quality of life impacts on residents and businesses represented by the elected official.

Fire and emergency medical services (EMS) advise the event planning team on the provision of emergency access routes to and from the event venue.

The media functions to disseminate pretrip event and associated travel information, in addition to real-time information on traffic and transit conditions during the day-of-event to assist event patrons and other road users. A media representative may participate in a meeting of the event planning team to obtain advance information on proposed temporary traffic control, transit, and travel demand management initiatives. However, the media generally works independently of the traffic management team on the day-of-event.

Private industry satisfies a wide range of public agency needs from the event operations planning phase through the day-of-event activities phase. Traffic engineering consultants may assume the role of a public agency traffic engineer and in turn, develop a transportation management plan and manage either an event planning team, traffic management team, or both. Private traffic control vendors, such as barricade companies, fulfill the duties of a transportation agency maintenance department. ITS equipment vendors contract with transportation agencies to: 1) install permanent equipment such as CCTV cameras, lane control signals, dynamic trailblazers, and parking management systems on surface streets serving a fixed event venue or 2) deploy portable traffic management systems, including portable CCTV, portable changeable message signs, portable HAR, portable vehicle detectors, and portable traffic signals. In some instances, transportation agencies may arrange for an equipment demonstration, at no cost to the agency, to evaluate the performance of a particular technology application during a planned special event.

Regional coalitions interact with both the administrative team and an event planning team regarding major planned special events affecting a regional area. A metropolitan planning organization (MPO) oversees the planning and programming of transportation management strategies. For example, the agency may communicate and seek feedback on temporary travel demand management strategies with commuter groups and trucking companies. An MPO may loan staff to other public agencies in need of personnel to conduct planning and operations activities. The agency may also establish and/or coordinate temporary task forces charged with a particular function, such as event communications. A ROO, as explained earlier in section 2.3, consists of traffic operations agencies, transit agencies, law enforcement, elected officials, and other operations agencies focused on the operation and performance of a regional transportation system.

Government agencies denote nontransportation agencies that generally serve in an administrative capacity. A government office responsible for special events may work in tandem with the event organizer to initiate the event operations planning phase and coordinate event planning team stakeholders. Other governmental emergency management and security agencies may meet with the event planning team to obtain an advance debrief on transportation management plan specifics.

The public represents individual residents, businesses, and associated community groups. Residents and businesses potentially impacted by intense traffic and parking demand generated by a planned special event may interact with event planning team stakeholders during a public meeting. This permits concerned citizens the opportunity to review and discuss proposed traffic and parking restrictions needed to accommodate event traffic.

In summary, the complexity of special events requires a much larger group of stakeholders than other corridor management applications. To achieve corridor level operations, it is necessary to take special event management to a broader level of involvement, which expands the number of stakeholders involved. The large number of stakeholders may require the development of a more multifaceted organization structure to effectively deal with the complexity cause by number of issues and the number of agencies involved.

The goals, objectives and performance measures of planned special event coordination should be established before working on the strategies to improve corridor operations. This allows the partners to define broadly what they are willing to do, before defining where and how they will do it. By starting with goals, the partners can define what aspects of corridor special event coordination they believe they can undertake. This is an important step because not all parties may see the goals for special event coordination the same way. It is easier to understand conflicts at the goal level because they are general in nature.

The potential impact of a planned special event is often difficult to predict and measure. However, establishing goals provides the necessary focus to understand what is potentially achievable through corridor coordination. Some candidate goals from Managing Travel for Planned Special Events include:(25)

Specific objectives include:

The corridor concept of operations is a formal document that provides a high-level, user-oriented view of operations in a specific corridor. It is developed in part to help communicate this view to the other stakeholders and to solicit their feedback. In essence, the corridor concept of operations provides a description of the current system, operating practices and policies, and existing capabilities. It lays out the program concept, explains how the corridor system is expected to work once it is in operation, and identifies the responsibilities of the various stakeholders for making this happen. The goals, objectives, and performance measures of a proposed operation are also documented. The process of developing a concept of operations for a corridor should involve all stakeholders and serve to build consensus in defining the goals and objectives; to provide an initial, definitive expression of how functions are performed, thereby supporting resource planning; and to identify the interactions between organizations.

The planned special events management concept of operations is the document that creates the high-level understanding of the planned special event management program. The concept of operations represents the initial support for the program and records the agreed upon approaches to be pursued in more depth.

The basis of the planned special events management concept of operations is the development of high-level problematic issues that warrant corridor-level special event response. The issues are presented as scenarios developed from problems identified in the first step in the framework. Problems whose alleviation is consistent with the corridor goals and objectives would be candidates for mitigation developed into high-level issue statements.

Problematic issue statements represent the initiating event for mitigation of the effects of special events. At the concept of operations stage, issues are broad: they do not focus on specific strategies. An example of this level of strategy could be to facilitate access to a special event venue by providing improved traffic management involving traveler information and revised traffic signal control on the major access routes.

At this stage, the cooperating agencies answer the questions of what (not how) they would be willing to do in the corridor to coordinate operations in response during a special event. General strategies could include:

The general strategy might be to use existing freeway DMSs to alert freeway drivers to the event so they might avoid the venue and seek an alternative route. Another high-level strategy might be to provide special arterial signal timing at the freeway exit to reduce freeway congestion.

The development of a concept of operations allows participating agencies to agree on what they wish to accomplish and to lay the framework for how that will be done. For example, does the traveler information only describe the nature of the problem or does it provide recommended courses of action? This is an example of an issue the agencies should resolve before moving to the more detailed level of discussion.

As part of the development of a concept of operations, consider the following points:

The concept of operations document often includes the following sections:

In summary, the concept of operations defines the high-level problematic issues that will be used to address the defined problems consistent with the corridor goals and objectives. The detailed issues and strategies have to be worked out in the development of the corridor implementation plan. The concept of operations phase of planning involves the who, what, when and where of special event coordination. The corridor implementation plan will determine how it will be done.

The main objective of CFA operations during planned special events is to maximize system effectiveness. Traveler information can mitigate demand, influence mode choice, influence route selection, and otherwise improve traveler reaction to negative impacts of the event. Better coordinated control systems increases throughput and minimizes impacts on motorists not attending the special event, but traveling on the roadways in the area.

Table 10 lists example strategies for mitigating the impacts of planned special events on local roadway and regional transportation system operations. In meeting the overall travel management goal of achieving efficiency, these strategies target the excess capacity of the roadway system, parking facilities, and transit. Through travel demand management, event planning team stakeholders develop attractive incentives and use innovative communication mechanisms to influence event patron decisionmaking and ultimately traffic demand.

| Category |

Example Strategies |

|---|---|

Traffic Management and Control |

|

Freeway management |

Ramp closures. |

Arterial management |

Access and turn restrictions. |

HOV incentives |

Public transit service expansion. |

Traveler Information |

|

En route traveler information |

DMSs (temporary and permanent). |

Local travel demand management |

Background traffic diversion. |

Pretrip traveler information |

Internet. |

Shared Information and Resources |

|

Incident response |

Motorist service patrols. |

Traffic surveillance |

CCTV systems. |

Information systems |

Incident reports. |

Special Events Management |

|

Event patron incentives |

Pre-event and postevent activities. |

Bicyclist accommodation |

Bicycle routes and available parking/lock-up. |

Shared resources represent one of the potential major benefits of coordinated operations during special events. Through sharing resources, collaborating agencies can make available more information than they might individually provide. Since a major special event is likely to have a substantial spillover effect, shared resources are a win-win proposition.

As discussed previously, the process of selecting the specific strategies is an iterative process involving assessment of the costs and the benefits of the various strategies as well as the stakeholder agencies' ability to implement the strategies. Each of the participating agencies must be comfortable with the strategies and be capable of implementing them.