U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

California Division

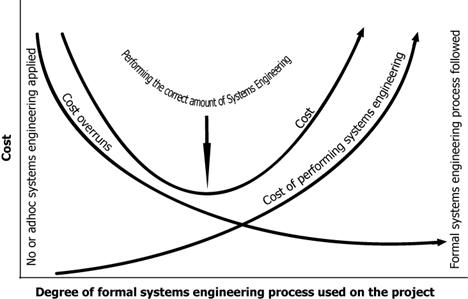

OBJECTIVE: This chapter provides guidance on how much process [or project tailoring] is needed for ITS projects. It describes ways to assess the degree of formal process needed to deliver the system with the required level of quality; assures that the project will meet the expectations of maintainability, documentation, and functionality; and address all the key risk areas. |

Figure 4‑8 Degree of Formal Systems Engineering

How much process is needed for a given project?

This is a difficult question to answer but one that needs to be addressed. Tailoring of the systems engineering process is a key initial activity for the systems engineer. It is not always based upon a single factor [cost or size].

The amount of formal process is a question that cannot be fully answered quantitatively. Engineering judgment, experience, and institutional understanding are needed to “size up” a project. As the project is being carried out, the focus should be on the end-product to be delivered. It should not be on the process to follow. In the ideal world the product delivered should carry just enough systems engineering process, documentation, and control to produce it at the desired quality level. No more and no less. There is a balance that needs to be kept and continually monitored. Illustrated in Figure 4‑8 is a notional graph that depicts this balance. Mr. Ken Salter[1] adopted this analysis for systems engineering. It shows that we need to look at each ITS project and assess the amount of systems engineering that needs to be done. This is the tailoring process that a systems engineering team performs as part of project planning.

The amount of process needed for a project depends upon the following factors:

As a starting point for estimating the percent of effort, the Table 4‑4 can be used.

Table4‑4 Estimate of Percent of Effort in SE

| Planning | Definition | Design | Implementation | Integration/ Verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 15% | 20% | 30% | 25% |

The following two examples are used to illustrate the amount of systems engineering needed in a very simplistic way. In Chapter 4.10 there is an elaboration of each of these examples.

Example 1: Adding field elements to an existing system. [See Chapter 4.11.1 for more details] The following is a brief description of the example project:

A $10 million project will add 30 full matrix changeable message signs [assuming $330K per sign] to an existing system which has five of these same signs already deployed. No other changes to the central or field equipment are needed [including no required changes to the communications network]. The system was initially designed to accommodate these additional signs so no additional software is needed. The assumptions for this example is as follows:

This example represents the adding of more field equipment [changeable message signs, cameras, traffic signals, and ramp metering] to an existing system. In this example, the assumptions are that the existing system was originally designed to accommodate the added elements and no additional design work is needed. In this example, the project risks are fairly low, there is a minimal number of decisions to be made, project complexity is low, common inter-faces have been established, and minimal stakeholder issues exist. One may assume the same documentation which implemented the original system is adequate for the expanded system. In this example, little systems engineering is warranted, other than a cursory review of system engineering products already delivered. However, it is recommended that a review of the existing documentation be done to ensure no adverse effects will occur when the additional elements are added to the system.

Example 2: Builds on the first example but adds a new requirement for sharing control with another partner agency. [See Chapter 4.11.2 for more details] The following is a brief description of the example project:

This example has introduced additional risks, additional decisions to be made, a broader set of stakeholders, and added complexity in functionality and interfaces. Further, there is the risk that the existing system cannot be easily changed to accommodate the new functionality. In this example the application of systems engineering is warranted to address these issues. It is interesting to observe that, even though the cost estimate for this example adds only 5-6% more to example 1, the issues mentioned above plus the addition of a custom development of software and changes to the existing system drove the need for more formal systems engineering. The message is that cost alone is not a driver in defining the level of required systems engineering. Defining the appropriate level requires looking at a number of inter-related issues.

Each project is unique. We recommend that each project be assessed on its own merits as to the amount and degree of formal systems engineering that is needed. This tailoring is a systems engineering responsibility that occurs at the onset of each project.

Example areas of project tailoring

Project tailoring is done as part of the project planning. It is included in the Systems Engineering Management Plan [SEMP] which is described in Chapter 3.4.2.

[1] LA Chapter INCOSE presentation 2003, JPL Pasadena