U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-13-091 Date: November 2014 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-13-091 Date: November 2014 |

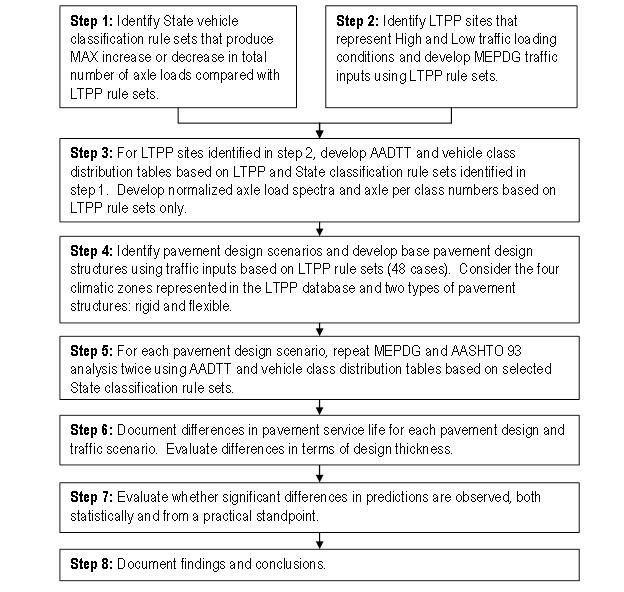

The sensitivity analyses were carried out using the algorithm presented in figure 18. The effects of different traffic loading inputs (resulting from differences in vehicle classification rule sets) were investigated by subjecting the same base pavement structure to different VCDs and volumes associated with the application of different vehicle classification rule sets (see table 15 and table 16) and observing differences in predicted pavement service life.

In each successive sensitivity run, differences in predicted pavement performance were observed and quantified. The number of years until at least one of the distresses or IRIs would reach its terminal value was recorded for each run. Findings regarding the sensitivity of pavement design outcomes to differences in vehicle classification rule sets are reported in the following section.

Figure 18. Chart. Steps for conducting sensitivity analysis.

Table 19 provides a summary of differences in pavement service life predictions using traffic inputs based on different classification rule sets. Negative values represent a decrease in pavement life while positive values represent an increase. In addition, the last two columns on the right show whether differences in traffic led to a difference in pavement design thickness that is more than 0.5 inches. The 0.5-inch minimum design thickness difference was used because it has practical significance from constructability point of view.

Table 19. Summary of pavement life predictions from MEPDG sensitivity analyses.

Pavement Type |

Functional Class |

Climatic Region |

Failure Mode (Terminal Value) |

Design Life (Years) |

Change in Predicted Design Life (Years)1 |

Relevant Impact (Change in Design Thickness) (Inches) |

||||

LTPP |

WA |

CA |

WA |

CA |

WA |

CA |

||||

Rigid |

Rural Interstate |

Wet No Freeze |

Slab Cracking (15%) |

20.3 |

19.9 |

20.9 |

-0.4 |

0.6 |

— |

— |

Wet Freeze |

Slab Cracking (15%) |

20.1 |

19.8 |

20.7 |

-0.3 |

0.6 |

— |

— |

||

Dry Freeze |

Slab Cracking (15%) |

20.1 |

19.8 |

20.7 |

-0.3 |

0.6 |

— |

— |

||

Dry No Freeze |

Slab Cracking (15%) |

19.8 |

18.8 |

19.8 |

-1.0 |

0.0 |

— |

— |

||

Rural Other Principal Arterial |

Wet No Freeze |

Slab Cracking (15%) |

21.1 |

13.8 |

21.1 |

-7.3 |

0.0 |

> 0.5 |

— |

|

Wet Freeze |

Slab Cracking (15%) |

24.8 |

16.7 |

24.8 |

-8.1 |

0.0 |

> 0.5 |

— |

||

Dry Freeze |

Slab Cracking (15%) |

21.9 |

14.2 |

22.0 |

-7.8 |

0.1 |

> 0.5 |

— |

||

Dry No Freeze |

Slab Cracking (15%) |

20.8 |

13.1 |

20.8 |

-7.8 |

0.0 |

> 0.5 |

— |

||

Flexible |

Rural Interstate |

Wet No Freeze |

Rutting (0.75 inches) |

17.8 |

16.8 |

17.8 |

-0.9 |

0.0 |

— |

— |

Wet Freeze |

Rutting (0.75 inches) |

17.7 |

16.8 |

17.8 |

-0.8 |

0.1 |

— |

— |

||

Dry Freeze |

Rutting (0.75 inches) |

16.8 |

16.0 |

16.8 |

-0.8 |

0.1 |

— |

— |

||

Dry No Freeze |

Rutting (0.75 inches) |

15.1 |

14.8 |

15.3 |

-0.3 |

0.2 |

— |

— |

||

Rural Other Principal Arterial |

Wet No Freeze |

Fatigue Cracking (25 percent) |

17.9 |

15.6 |

18.0 |

-2.3 |

0.1 |

— |

— |

|

Wet Freeze |

Fatigue Cracking (25 percent) |

17.8 |

15 |

17.9 |

-2.8 |

0.1 |

— |

— |

||

Dry Freeze |

Fatigue Cracking (25 percent) |

15.4 |

12.9 |

15.7 |

-2.5 |

0.3 |

— |

— |

||

Dry No Freeze |

Fatigue Cracking (25 percent) |

17.5 |

15.1 |

17.7 |

-2.4 |

0.2 |

— |

— |

||

— No impact

LTTP = Long-Term Pavement Performance

The results presented in table 19 indicate that the California WIM and California AVC classification rule sets, which correspond to classification differences that produce the most significant decrease in cumulative traffic load used for design (when combined with load spectra collected using the LTPP rule set), resulted in very small changes to pavement design life (less than 1 year) for all design cases (road types, pavement types, and climatic zones). These small changes correspond to minimal variations in design thickness that are less than 0.5 inches and do not affect the practical outcome of the design (i.e., the final design structure did not change as a result of these variations).

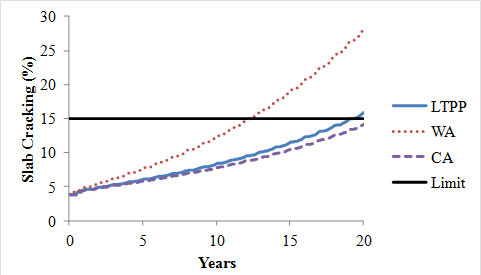

The Washington WIM-based classification rule set led to more significant changes, especially for low-volume ROPA roads. The Washington WIM is the classification rule set that corresponds to classification differences that produce the most significant increase in cumulative traffic load (when combined with load spectra collected using the LTPP rule set). Both pavement types designed for the ROPA road class had their design life reduced (up to 8.1 years for rigid and 2.8 years for flexible). For rigid pavements, this reduction in life can be mitigated only if the slab thickness is increased by more than 0.5Â inches, which is significant from the practical standpoint. However, because rigid pavements generally are not used for low truck volume roads, this outcome may have limited practical implications. The results for flexible pavement, although they reflected almost 3 years in design life loss, did not yield increases in design thickness that would be relevant in practice, because less than 0.5 inches was required to mitigate the reduction in design life.

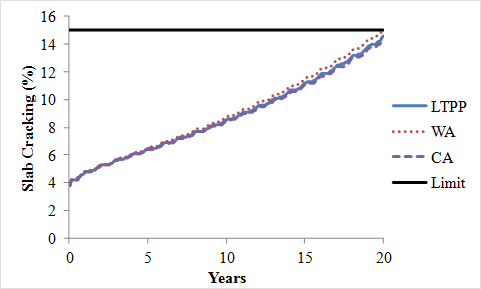

None of the design cases for the RI functional class had significant changes in design life when any of the classification rule sets were considered.

Of all the MEPDG failure modes observed in this sensitivity analysis, PCC slab cracking was found to be the most sensitive to changes in vehicle classification and volume, especially in the case of designs for low truck volume. The reason for this high sensitivity was investigated further. The MEPDG PCC slab cracking model is highly dependent on subgrade/base support of the PCC slab. It is also influenced by the number of heavy load repetitions. The ROPA roads were designed using the recommended layer structure in the MEPDG for low-volume roads. The PCC slab was thin (8 inches), and the base layer was crushed stone, which is less strong than the cement-treated bases usually used for interstate pavement structures. In addition, the Washington WIM classification scenario increased the total volume of heavy trucks (in Classes 6 through 13) by 59.4 percent for the ROPA test, compared with a 3.4-percent increase for the RI test. These two conditions combined were responsible for the high sensitivity of rigid ROPA designs to changes in truck volume and class distributions when different vehicle classification rule sets were used.

Figure 19 and figure 20 show an example of the impact of different vehicle classification rule sets on the performance of rigid pavements designed for RIs and ROPAs for the wet-freeze climate condition. Slab cracking was the critical distress that led to pavement failure. The impact of increased volume of heavy trucks, represented by the Washington WIM rule set, is more evident and substantial for ROPAs than it is for RIs. The reduction in predicted service life in this example was 7.3 years for ROPA design, compared with a slight increase in service life when the traffic rule set with lighter trucks was used (California).

Figure 19. Graph. MEPDG performance predictions for wet-no freeze condition for rigid pavements: ROPAs.

Figure 20. Graph. MEPDG performance predictions for wet-no freeze condition for rigid pavements: RIs.

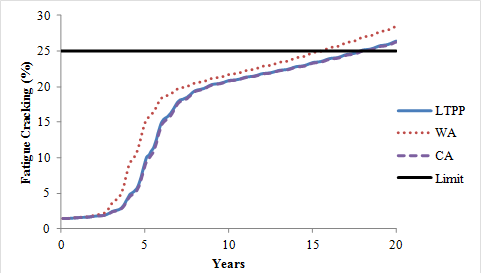

The sensitivity of flexible pavement designs to truck volume and class changes also was more evident for ROPAs than RIs in flexible pavements, although the difference was not quite as significant as it was for rigid pavements. Different subgrade types were considered for ROPAs and RIs to reflect the need for better underlying material in RI designs. This is often done by stabilizing the top portion of the subgrade and/or adding a subbase. In the case of this research, the subgrade type was modified in the MEPDG to account for this difference and to keep the design as simple as possible. Besides the difference in subgrade type, the two road type designs also had differences in the thicknesses of the surface and base layers. However, the same material type for base and surface layer were used for both structures. The failure mode for ROPAs was fatigue cracking, which is dependent on the strength of the AC surface layer, as well as the stiffness of the layer underneath the surface layer. The failure mode for RIs was rutting, which is dependent on all layers’ material stiffness and thickness. The higher sensitivity to changes in traffic volume and class observed for the ROPA designs is a direct consequence of the addition of 35-percent more trucks (Classes 4 through 13) to the truck volume for the ROPA analysis, compared with a 2.4-percent truck volume increase for the RIs. These additional volumes resulted from the application of the different vehicle classification rules, given the makeup of the traffic stream at the two test sites.

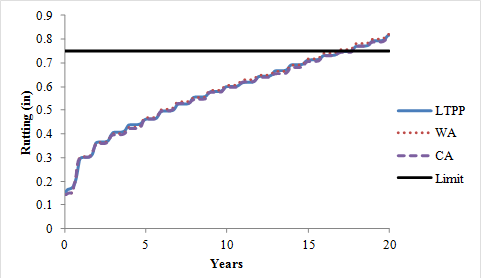

Figure 21 and figure 22 show an example of the impact of different traffic classification rule sets in the performance of flexible pavements designed for RIs and ROPAs for the wet-no-freeze climate condition. Fatigue cracking was the critical distress over the design life, measured in years, for ROPAs, while rutting was the critical distress for RIs. The impact of increased volume of heavy trucks, represented by the Washington WIM rule set, is more evident and substantial for ROPAs than it is for RIs. The reduction in predicted service life for ROPAs in this example was 2.3 years, compared with no change in predicted service life when the traffic rule set with lighter trucks was used (California).

Figure 21. Graph. MEPDG performance predictions for wet-no freeze condition for flexible pavements: ROPAs.

Figure 22. Graph. MEPDG performance predictions for wet-no freeze condition for flexible pavements: RIs.