U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-17-072 Date: February 2018 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-17-072 Date: February 2018 |

This section presents evaluation findings for each of the four hypotheses by addressing the evaluation questions using the key performance measures. This section is broken up into four separate subsections as detailed in the following list:

• 4.1: FHWA P3 Program use increases legislative and policy support for transportation P3s in State and local governments (referred to as Legislative and Policy Support).

• 4.2: The FHWA P3 Program has led to more informed decisions on consideration and use (approval) of P3s for appropriate transportation projects (referred to as P3 Consideration and Use).

• 4.3: The FHWA P3 Program improves the decisionmaking capabilities of transportation practitioners in the areas of P3 development, procurement, and oversight (referred to as Practitioner Decisionmaking).

• 4.4: The FHWA P3 Program provides the most complete set of information resources to assist transportation practitioners in all phases of the P3 implementation process (referred to as Complete P3 Resource).

As States continue to assume a larger share of infrastructure project funding and need to develop funding and financing solutions, transportation leaders are more often considering P3s as a financing alternative.(45) As a result, enabling legislation and other P3-related bills are increasingly submitted to State legislatures for consideration. Such legislation determines which government entities are permitted to engage in P3 agreements, for which type of projects, and under what terms and conditions. Statutes and bills vary from State to State depending on the specific needs and desires of each State, and legislation updates are submitted as new project situations or challenges arise. This section of the evaluation examines the impact of the P3 Program on P3-related legislation and policy at the State and local level.

This section reviews how State legislators and policymakers are informed about P3s and the P3 implementation process, allowing them to make informed legislative and policy decisions. The evaluation team sought to identify the specific materials, trainings, and knowledge partners that bring P3 information to the legislative and executive branches. The role of the P3 Program and its resources was assessed using the following two evaluation questions:

The evaluation team attempted to schedule interviews with States who recently passed P3 enabling legislation and was successful in reaching legislative contacts from three States new to P3s. Interviews with legislative and State transportation department contacts in four other P3-enabled States offered additional insights on how P3 information reaches legislators and policymakers. In addition, information from the P3 Program activity database and P3 Toolkit website downloads was examined in an attempt to link the P3 Program to those involved with P3 legislation.

The evaluation team reviewed P3-related legislative activity for 3 years (2013–2015) as well as P3 enabling legislation from 2016 and years prior. This information allowed the team to assess the level of interest in P3s across States and to identify the State and local agencies who were likely to be looking for P3 information. Figure 9 shows five different time periods from 2000 to 2016 detailing the number of States passing P3-enabling legislation.

The legislative activity and enabling legislation review showed that six legislative bodies had passed P3 enabling legislation since the 2013 release of the FHWA P3 Toolkit and the start of the P3 Program. Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Hampshire, and the District of Columbia recently passed the legislation, making them potential candidates for P3 Program use. Representatives from three of these States were interviewed.

A review of all legislative activities involving P3s pointed to the fact that more than just a few States were actively pursuing legislation related to transportation P3s. In the P3 Program period (2013–2015), the number of P3-related bills proposed more than doubled compared to the previous 3-year period (2010 to 2012). Each year more than 20 States were pushing P3-related bills. In total, this hot topic was addressed in 36 States/territories during the P3 Program period. Several States continue to pursue enabling statutes, while others are updating P3 laws to approve P3 procurement on new projects, allow for tolling or availability payment terms, establish P3 Program offices, and support multiple other issues. Table 6 summarizes this information.

N/A = not applicable.

Despite increases in P3 legislation in recent years, P3 Program usage data and interviews with States who recently passed P3-related legislation suggest that there is currently not a strong connection between the P3 Program and legislators and policymakers. Few directly involved in legislation used P3 Program resources. This does not mean, however, that information from the P3 Program does not reach this audience. In many cases, the link between the P3 Program and those in legislative or policymaking positions is indirect. That is, the P3 Program provides knowledge to Federal, State, and local transportation agencies and P3 advisors, who then bring the information (along with other knowledge and experience) to decisionmakers. The P3 Program also provides content that is used by other websites and interest groups who develop materials that more directly target legislators and policymakers.

The first evaluation question examined whether the P3 Program provided State and local governing bodies with information on P3 opportunities and challenges that informed their decisions to seek P3 legislation. The second question was designed to uncover how P3 Program resources informed the development of specific legislation and policies. Challenges in identifying, contacting, and recruiting those involved with P3 legislation or policy development made it difficult to answer either of these questions. Even those whom the evaluation team were able to interview did not provide a direct link between the P3 Program and legislation in their States.

The review of P3 Program usage data uncovered only a handful of cases where legislative or executive staff from States recently passing P3-legislation had used P3 resources. The evaluation team interviewed one of these P3 Program resource users who was co-director of a newly created P3 office. The contact was heavily involved in drafting a recent P3 legislation update. Although he had identified usage of P3 Program materials, including fact sheets and primers, he noted that these materials had not played a role in informing the legislation. Another interviewee, a legislative analyst who managed the development of enabling legislation for his State, lamented that he found the P3 Toolkit only after the legislation was complete, as a result of the evaluation team interview.

Formal and informal barriers between State transportation departments and P3 offices and those in elected positions make direct information sharing between the groups difficult. Although State and local agencies are among the most frequent users of P3 Program resources, this usage does not often extend to those involved in legislation and policy development. Protocol and politics often limit informal interactions between the government entities, leading to limited direct sharing of P3-related information resources with the legislators and policymakers themselves.

Despite the lack of evidence of direct use of the P3 Program, there is evidence that information from the P3 Program has some influence on P3 legislation and policy. P3 information pulled from sources such as the P3 Program is brought to legislators and policymakers by State transportation departments and P3 Offices during formal presentations and interactions. The manager of a State P3 team, who encourages his staff to attend webinars and use P3 Program materials to keep current, describes the roles his agency has in legislation:

The legislative liaison for the transportation department in the same State shares a similar message:

Other State transportation departments active with the P3 Program provide other examples of how they have brought their knowledge of P3s to the legislative and executive branches.

Information from the P3 Program also reaches legislators and policymakers through other P3 education resources. Interviewees involved in developing State legislation mentioned the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) website.(46) This website has several resources for States, including P3 enabling statutes,a Transportation Funding and Finance Legislation Database, and a P3 Toolkit for Legislators.(45,47,48) The Toolkit for Legislators and other P3-related content pages on the NCSL site references material that is currently part of the P3 Toolkit, including P3 definitions, case studies, and model legislation.

To consider this hypothesis, the evaluation team focused on the following evaluation questions:

To investigate these questions, the evaluation team sought information that showed a link between use of P3 Program resources by practitioners at the State and local level and the consideration and approval decisions for P3 projects.

Neither the program usage data nor the interviews provided solid evidence that P3 Program usage impacts P3-project-consideration decisions. States using the P3 Program were shown to be slightly less likely to announce consideration of a P3 project than those who did not. The interview responses lacked specific information on what sources of information (P3 Program or others) contributed to the decisions. It was not possible to determine whether P3 Program users made more rigorous screening decisions or whether information from the program was just not contributing to the decisions.

The lack of data stems from the difficulty the evaluation team had identifying decisionmakers who screened projects for P3 consideration. The interviews indicated that the screening process differs from State to State and sometimes from project to project. To better understand the relationship between P3 Program resources and P3 project consideration, additional research is recommended. As the P3 Program matures and its user base increases, time could be spent identifying the different groups who make project screening/consideration decisions. The decisionmakers could then be interviewed to better understand if and how the P3 Program influences consideration.

There is more evidence to support the idea that P3 Program resources help States make informed P3 approval decisions. Recent data show that only about 30 percent of P3 projects announced in the PWF major projects database for the years 2013–2015 were approved. Some of the projects were cancelled or put on hold, while others ultimately moved forward using other types of procurement. P3 Program use was associated with the vast majority of States who recently approved transportation P3 projects. Interviews with State and local agencies indicated that knowledge gained from the P3 Program was often used to support the case in favor of P3s. Examples describe teams leveraging P3 Program documents, trainings, and personnel to ease fears about P3s and gain support needed for approval. The combination of P3 Program usage data and anecdotal evidence allow the reasonable conclusion that use of the P3 Program provides knowledge that can be directed to support P3 approval when appropriate. As the P3 Program matures and additional usage data are available, the connection between the P3 Program materials and P3 approval decisions can be more thoroughly researched.

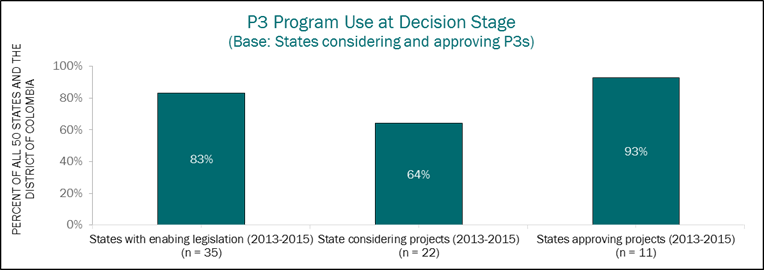

The proliferation of P3 projects during the last 3 years is evident from P3 project data. At the end of 2015, 35 States had enabling legislation that allowed for the use of P3s for major transportation projects.[7] From 2013 to 2015, 22 States considered 57 P3 projects. This is up significantly from the 10 States and 42 projects considered in the previous 3-year period (2010–2012). These increases signal that P3s are becoming more commonplace for major transportation projects. The bar chart in figure 10 summarizes this information.

P3 Program use was broken out by P3 project decision stages and determined using data from the PFW major projects database. The results show a non-linear relationship between P3 Program use and the project decision stages. Eighty-three percent of States who are able to use P3s have accessed P3 Program resources. Fewer (64 percent) who moved on to announce P3 project consideration had used the program. Almost all (93 percent) who approved P3 projects were P3 Program users. This information indicates that the relationship between P3 Program use and P3 project decisions may be complex. P3 Program use does not necessarily increase likelihood to consider and use P3s. The data were examined by phase to get further information. Figure 11 summarizes at what stage the P3 Program was used.

R&T Evaluations: Public-Private Partnership Capacity Building Program  |

n = number of States.

Source: FHWA

Figure 11. Chart. P3 Program use by decision stage.[9]

Figure 12 breaks the 35 P3-eligible States into two groups: known users of the P3 Program and non-users. Comparing the percentage in each group who announced a project in the PWF major projects database during the 3-year period 2013–2015 provides some idea of whether P3 Program usage influences consideration. The results show that 67 percent of States with no P3 Program use considered a P3 project. A similar proportion, 62 percent of P3 Program users, also considered projects. This result does not indicate that P3 Program use leads to more P3 project consideration.

There could be several different reasons explaining the results shown, including the following:

Interviews with State and local transportation departments and P3 offices did not provide much information that clarifies the relationship between the P3 Program and project consideration. The interviewees often became involved in the P3 projects after they were proposed, so the evaluation team was unable to probe what information was used to help teams make consideration decisions.

The interviews did reveal that States have very different processes for initiating potential P3 projects. In some States, the transportation departments and P3 offices recommend projects. In others, P3 recommendations came from P3 advisory committees or elected officials, and sometimes P3 requests came from the localities themselves:

Detangling the role the P3 Program plays in the consideration decisions would require identifying and speaking to a unique set of decisionmakers in each State relatively soon after project decisions were made. Such research was out of scope for this evaluation. As a result, claims suggesting the P3 Program influences P3 project consideration decisions cannot be supported at this time.

Information from the PWF major projects database was also used to look at P3 Program influence on project approval decisions. Of the 22 States considering P3s since the P3 Program was launched, 4 were categorized as non-users while 18 were known users of P3 Program resources. Of the non-users, only 1 of 4 (25 percent) approved a P3 project during this time. This is compared to 9 of the 18 (50 percent) P3 Program users. Figure 13 depicts this information.

Despite the small size of groups, this breakdown indicates that P3 Program use may have an impact on the approval decisions of P3 projects. Knowledge gained from P3 Program use, by itself or in conjunction with other information, may help teams make a stronger case for approval of their P3 projects.

The interviews with P3 Program users did not yield much information on which specific P3 Program resources impacted P3 approval decisions, but they did provide examples showing P3 Program users bringing their knowledge of P3s to decisionmakers to make the case for P3 approval.

P3s bring together the public and private sectors to implement major transportation projects. The process takes multiple years to complete and includes multiple phases, each with data collection and decisionmaking. Once P3 legislation and policy are in place to enable State and local agencies to consider P3 projects, the process moves on to the phases that include P3 screening, evaluation, procurement, and then finally implementation. The P3 Program offers information resources that can assist practitioners as they make decisions in each of these phases.

This hypothesis covers decisions made across the entire P3 implementation process. These decisions are typically made by those in State or local agencies but are supported by FHWA Division Office staff and P3 advisors/consultants. Three evaluation questions were developed to adequately address the role the P3 Program resources play in providing information and building knowledge within each of these distinct user groups:

Each of these evaluation questions has the potential to cover most of the publications, tools, and trainings available through the P3 Program. Where information is available, the evaluation covers how the materials and trainings provide knowledge that influences decisionmaking at different phases of the P3 implementation process. In many of the interviews conducted by the evaluation team, P3 Program usage was relatively recent and/or P3 projects had not progressed past the planning and evaluation phases. In these cases, usage of the program and knowledge building is summarized more generally.

Interviews with those at State and local agencies identified some strengths and weaknesses of the P3 Program. The sweet spot for the P3 Program seems to be States with less P3 experience who have a direct relationship with the P3 Program. Interviews and the P3 Activity Database identified several of these States where the P3 Program had recently provided support in the form of trainings, peer exchanges, or other activities. Practitioners in these States took advantage of the educational activities and also directly accessed P3 Toolkit resources, using them to make P3 decisions during the P3 planning, evaluation, and procurement phases. Practitioners in less experienced States, who do not have a direct relationship with the P3 Program, indicated they struggled to find the right resources through the P3 Program to help them make P3 decisions. Lastly, the P3 Program was seen as least useful by very experienced P3 States, most of whom had their own P3 education programs in place before the P3 Program launched and who use their own P3 materials.

A limited set of interviews was available to determine how P3 advisors use and value the P3 Program. Although the P3 activity database and P3 Toolkit website downloads indicate that P3 advisors (legal, finance, and engineering) are a major user group, it was difficult to recruit these practitioners for interviews. The few interviews conducted led to findings similar to those from State and local agency interviews. Experienced practitioners at established firms see value in the P3 Program through its use as an introductory resource but rarely use or recommend more complex applications such as the P3-VALUE Tool. Some newer employees at P3 advisory firms, however, did report attending webinars and using documents from the website. The interviews paint a picture of limited P3 Program use among advisors, but usage data and P3 Toolkit website downloads show that, as a whole, advisors are an important user group. Additional research is recommended to understand more about this large user group, their use of the P3 Program, and their information needs.

P3 Program resources are becoming more important for FHWA Division Office staff as more and more States are considering and pursuing P3s. An online survey conducted for the evaluation identified that 34 percent of respondents in roles that may support P3 teams have accessed the P3 Toolkit website or attended webinars. Those in project development/major projects and finance roles tend to be the most frequent users. They look to the P3 Program for materials as they help teams at each stage of the P3 implementation process. FHWA staff help provide information and answer questions about P3s before planning begins. During planning and evaluation, they assist in developing financial and project management plans and help teams develop inputs for evaluation analyses. During procurement, they advise on request for proposals (RFP) development and vendor selection processes. Finally, during oversight they help teams manage Federal reporting requirements. P3 Program documents and webinars provide information that FHWA staff share with State and local agencies. Oversight documents, model contract guides, and project agreements provide specific information and examples used for developing project documents, while fact sheets and primers provide general P3 information for other requests.

Interviews with representatives of 10 active P3 States combined with information from the P3 Program usage databases helped inform the evaluation question focused on the value of P3 Program resources to P3 project decisionmaking. Because of differences noted in initial interviews, the States were divided into those who are more experienced with P3s, having completed multiple P3 projects, and those who are newer to the P3 implementation process.

Transportation leaders from three of the most experienced P3 States said their agencies rarely use P3 Program resources. Even though these States were active contributors to the development of the P3 Program, leaders describe limited use of the resulting materials by their agencies. These agencies have years of experience with P3s and generally rely on their own experiences, materials, and trainings to educate employees for decisionmaking.

The same P3 Team leader did note that his State participates in peer exchanges, during which they contribute but also learn.

P3 Program usage data and interviews did confirm that there is some usage of the P3 Program materials among more junior team members in these experienced States. The P3 Program may not be the primary source of information for these States, but there is still value in some of the more foundational materials to junior team members.

Interviews with newer P3 States identified several practitioners who are highly engaged with the P3 Program. Practitioners from two States described customized P3 training events developed for their agencies, while one described regular contact with P3 Program staff. All described use of the P3 Toolkit website materials and spoke of webinar attendance by members of their teams.

A State office focused on innovative finance solutions for transportation projects described P3 Program use at multiple phases of the P3 implementation process. Fact sheets and guidance documents helped newer employees as well as senior managers get an overview of P3s, while a peer exchange provided “valuable examples of how other States handled risk allocation, outreach and procurement” that informed the P3 evaluation and procurement phases.

A program leader with a longstanding relationship with FHWA described how Value for Money (VFM) tools helped her move a P3 project forward during the P3 planning and evaluation phases.

Another practitioner in the same State, who had not yet managed a P3 project, described using the P3 Toolkit website to learn about P3s more broadly and to investigate examples of types of P3s (e.g., design–build–finance and design–build–finance–operate–maintain) for potential projects.

A project manager from a midwestern State that had done a P3 in the past, but is currently limited because of legislation changes, described a close relationship with the P3 Program. He described staying informed by using the P3 Program to “try to change the paradigm about P3 use in the State.” He describes having direct contact with the P3 Program staff, using documents pulled from the website, and attending webinars to support his case for P3s.

Other States newer to P3s described occasional use of P3 Program resources with less success. These practitioners did not have a direct connection to P3 Program staff. Some knew very little about the P3 Program itself despite attending a webinar. Others had only limited use of the website. A financial manager from a midwestern State doing her first P3 project described trying to use the VFM materials from the P3 Toolkit website. She gave up because her project used availability payments rather than tolls, which the material did not cover. Another user from the northeast looking for P3 financing information described coming across the P3 Toolkit website only after looking for P3 information on Google®. She, along with a few other respondents, described being “overwhelmed” by the P3 website and noted it was hard to find what she needed.

In total, seven P3 advisors/consultants from legal, finance, and general/engineering firms were interviewed. This section includes examples of how these advisors/consultants use P3 materials. Usage data show that many P3 advisors access the P3 Program webinars and website resources. It is likely that there are many variations to how P3 Program materials are used among P3 advisors, in addition to those described here.

A few experienced P3 advisors described using the P3 Program similarly to how it is used by experienced P3 States. These advisors contributed to the development of P3 Program materials, but their firms had only limited use of the final program materials. One legal consultant noted that P3 Program materials were more applicable to firms that hadn’t done P3s rather than those with years of experience. Another legal consultant said that most of the P3 team members in her organization pre-dated the P3 Program. She did mention letting clients and new employees know about webinars and primers, noting that they are valuable in providing a P3 foundation. In addition, an experienced financial consultant described both contribution to and use of P3 Program materials. He reviewed VFM materials but also finds value in using P3 project profiles.

Less experienced advisors describe occasional use of various P3 Program resources. An engineering consultant described attending a webinar to get an introduction to P3s but noted he did not have enough time to do all the work required. A junior legal consultant who attended some of the webinars saw value in learning about the business side of a P3. Another engineering consultant noted that he had tried to use the P3 Toolkit website but found it overwhelming and difficult to navigate. The interviews paint a picture of limited P3 Program use among advisors, but usage data and P3 Toolkit website downloads show that, as a whole, advisors are an important user group. Additional research is recommended to understand more about this large user group, their use of the P3 Program, and their information needs.

The evaluation team fielded an online survey with FHWA Division Office staff in positions that would engage with P3 teams at the State or local level (e.g., project delivery/major projects, finance, planning, and technical services). In total, 259 employees responded, representing all 50 States as well as Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. The evaluation team also conducted interviews with FHWA staff in eight States who recently passed P3 legislation or implemented P3 projects. The survey shows most States (44 of 52) had considered, pursued, or implemented transportation P3s. Thirty-four percent of respondents (88 of 259) indicated using the P3 Toolkit website or attending a webinar. The responses of these 88 P3 Program users provide insight into the information needs of FHWA staff and identify the P3 Program materials that help them meet their information needs.

P3 Program users primarily came from two specialties within FHWA Division Offices, project delivery (39 percent) and finance (33 percent). These positions will be the focus of this section. Responses from planning (17 percent) and technical services/other (11 percent) can be found in appendix B. The project and finance roles are covered separately, as they tend to describe different project activities and use of different P3 Program resources.

Table 7 shows the top support activities engaged in by those in project delivery/major project roles. Table 8 shows P3 Program resources accessed to inform the activities. Top activities include answering general questions about P3s and addressing Federal reporting requirements in contracts. Project staff also help develop RFPs and project management plans. The information resources used most often include webinars, fact sheets, primers, oversight documents, project agreements, and model contract guides.

The following comments show how support activities vary depending on the experience of the State or region:

Top Activities |

Percentage Used |

|---|---|

Answer general questions about P3s |

68 |

Ensure Federal requirements in P3 contracts are met |

62 |

Provide construction oversight |

57 |

Develop and/or review RFP |

54 |

Help and develop project management plan |

54 |

Top P3 Resource Use |

Percentage Used |

|---|---|

Webinars |

65 |

Fact sheets |

59 |

Primers |

38 |

Oversight documents |

32 |

Project agreements |

26 |

Model Contract Development Guides |

26 |

Table 9 shows the top support activities engaged in by those in finance related positions. Top activities involve developing financial plans and answering general P3 questions. Table 10 shows materials used to support these activities include webinars, fact sheets, and primers, along with past trainings. Oversight documents are also referenced. Those interviewed in finance positions described the following:

Top Activities Supported by Finance Positions |

Percentage Used |

|---|---|

Help develop and/or review financial plan |

84 |

Answer general questions about P3s |

68 |

Help develop and/or review the cost estimate review |

42 |

Research and provide material on complex P3 questions |

32 |

Help develop the project management plan |

32 |

Top P3 Resources Used |

Percentage Used |

|---|---|

Webinars |

79 |

Fact sheets |

59 |

Primers |

34 |

Previous training documents |

31 |

Oversight documents |

28 |

To understand whether the P3 Program provides a complete set of P3 resources that meets the information needs of transportation professionals as they undertake the P3 implementation process, the evaluation team considered program usage (see sections 3.1 and 3.2) as well as the following three evaluation questions:

Legislators and Policymakers: With few examples of direct P3 Program use by State legislators and policymakers, satisfaction could not be addressed.

State and Local Agencies: Practitioner satisfaction with P3 Program resources varies depending on experience level and involvement with the program. Those newer to P3s who are highly involved with the P3 Program were very satisfied. Others who had yet to form a personal relationship with the P3 Program tended to be more critical. Practitioners from experienced P3 States saw some value in introductory materials but were critical of more advanced tools.

FHWA Division Office Staff: According to the online survey, satisfaction levels were moderate to high among those in finance and project roles at FHWA Division Offices. Interviews with this audience confirmed that most appreciated the program’s offerings, although many had suggestions for improvement.

P3 Advisors: Satisfaction with the P3 Program varied depending on use. P3 advisors see value in introductory materials but rarely look to the P3 Program for more complicated topics, depending instead on their in-house experience and materials.

Legislators and Policymakers: Interviewees directly involved with recent P3 legislation say they primarily look to other States’ legislation for guidance and examples as they build their own. Experienced legal advisors were also described as critical to building P3 legislation. Another resource mentioned was the NCSL.(46)

State and Local Agencies: Consultants from advisory firms continue to play a major role in helping State and local agencies plan for and implement P3s. States have also created their own peer exchanges and sharing groups that bring real-life P3 examples and issues to the table. A small number of P3 team leaders and practitioners noted that they attend various P3 conferences and trainings, consult AASHTO, and use other sources.

FHWA Division Office Staff: FHWA Division Office staff note that they use information from other Division Offices. They also learned from experienced State and local P3 teams and from P3 advisors.

P3 Advisors: While leaders in experienced firms say consultants mostly learn in-house, others mention gathering information from organizations such as AASHTO and the Design-Build Institute of America.

Legislators and Policymakers: A legal counselor in a P3 Office noted that State legislators and policymakers need to see the highest levels of government advocating for P3s. He added that advocacy should be coupled with education and outreach. Another interviewee mentioned that access to existing legislation and tools to help States review legislation would be helpful.

State and Local Agencies: The most common challenge noted was that each P3 is different and that it is hard to find specific information to fill a State’s unique needs. Suggestions that the P3 Program could implement include organizing more small-group sharing events, creating forums for anonymous sharing of P3 lessons learned and “real-life” stories, and documenting best practices.

FHWA Division Office Staff: FHWA Division Office staff recognized that there were improvements that could help the P3 Program serve as a more complete P3 resource. Suggestions include developing materials on how to effectively communicate with all P3 stakeholders, providing more real-world examples of P3 projects, and/or providing a collection of lessons learned to guide FHWA staff and P3 teams.

P3 Advisors: To this group, the P3 Program is a source of introductory P3 information, but it is not seen as a complete resource for experienced practitioners. There is room for the P3 Program to fill information gaps by providing databases of actual evaluation inputs, more detailed cases, and project document libraries.

There is a path for information to travel from the P3 Program to State legislative and executive staffs, but that the path is indirect. The interviews the evaluation team conducted with those in roles related to developing legislation and policy indicate that few access the P3 Program directly for such purposes. Because of this, it was not possible within the scope of this study to determine which specific P3 Program offerings were used most often or to measure satisfaction with P3 Program materials.

State and local practitioners’ satisfaction levels with the P3 Program tend to be mixed. Those newer to P3s who were highly involved with the P3 Program are very satisfied. Several others from States that have yet to form a relationship with the P3 Program tend to be more critical of the program. States with advanced P3 Programs stated that they didn’t need the P3 Program to improve upon their own resources. Some felt the materials were good for those just beginning to learn about P3s, but others thought the materials were not focused enough and did not serve either beginners or advanced P3 teams well.

Satisfaction levels with P3 Program resources are moderate to high among those in project and finance roles. Those in finance roles were relatively evenly split between moderate and high satisfaction levels. Although more than half of those in project-related roles had high satisfaction, there was a small segment of this group that indicated low satisfaction (13 percent).

Figure 14 shows satisfaction level with P3 resources from FHWA Division office staff.

Overall, P3 advisors who used the P3 Program materials were satisfied with the foundation they provided on P3s, but use did not extend much further than that. There was some dissatisfaction with trying to find specific topics or documents on the website. The website was noted to be “overwhelming” by newer consultants. Others hoped for more project-specific content on the website, including specific concession agreements or cases with more project detail.

As noted previously, P3 advisors are among the most frequent downloaders of P3 Program documents. It is unclear how they have been using the P3-VALUE tools or related documents. Future data collection efforts could ask these respondents if they would be willing to take part in an interview or complete a survey designed to better understand their P3 Program use.

Interviewees directly involved with recent P3 legislation stated that they primarily looked to other States’ legislation for guidance and examples as they built their own. Another source mentioned by multiple interviewees was the website of the NCSL.(46) The Eno Center for Transportation training was also noted as a valuable source of real-world P3 examples and connections to private industry partners that helped teams as they developed P3 legislation.

Interviewees from State and local agencies say that States support each other in the development of P3 legislation and P3 projects. Practitioners describe experienced P3 States as being extremely helpful in providing legislation, contracts, and other documents that serve as templates for P3 projects. States have created their own peer exchanges and sharing groups that bring real-life P3 examples and issues to the table.

Advisors from legal, financial, and engineering firms also continue to play a major role in helping State and local agencies plan for and implement P3s. Practitioners from State transportation departments noted that they learned about P3s directly from advisors, used materials developed by the firms, and were able to access their documented cases as well as the direct experiences of team members.

A small number of P3 team leaders and practitioners noted that they attended various P3 conferences and trainings, consulted AASHTO, or used other sources. However, there were few sources besides the P3 Program that were common among them.

In addition to P3 Program resources, FHWA Division Office staff note that they use information from other States. They also learned from experienced State and local P3 teams and from P3 advisors. One Division Office staff member noted that peer-to-peer exchanges between State Division Offices have been crucial to staying up to date on best practices.

Several P3 advisors interviewed noted that they generally learned about P3s through their own firms. One consultant from an engineering-focused firm noted that they trained new employees on the job:

For new employees looking to obtain general P3 information, P3 advisors mentioned use of AASHTO and the Design-Build Institute of America. A legal consultant said that Westlaw[35] has developed a “large and expensive database that they utilize.”

The State representatives interviewed had several suggestions for how Federal-level agencies could improve the P3 legislation and policy development process. One legal counselor in a P3 office noted that a major barrier to passing P3 legislation is the lack of widespread acceptance of this type of contractual agreement in transportation. He noted that State legislators and policymakers need to see the highest levels of government advocating P3s. He later added that advocacy should be coupled with education and outreach to allow State and local governments to fully understand the P3 concept. He mentioned that knowledge gaps and lack of information lead to problems in crafting and implementing P3 legislation.

Another active legislative liaison noted that “getting the right legislators, the right information at the right time is critical. Those with backgrounds in finance would be prime targets for more complex documents, while others could just handle the basics.” He saw an opportunity to engage both State transportation departments and legislators as new legislation was on the horizon.

Others in active P3 states noted that experienced legal consultants and statutes from other States were critical elements in developing their own P3 legislation. One legislative analyst described assembling legislative “puzzle pieces” from multiple statutes to meet the needs of his State. Access to legislation and tools to help States review current legislation would be helpful to legislators as they tried to develop legislation and policy to meet their State’s needs.

State and local agencies identified several challenges to successful P3 use and suggested ways the P3 Program could help overcome them. One of the most common challenges noted was that each P3 is different and that it is hard to find specific information to fit a State’s unique needs. Suggestions the P3 Program could implement included organizing more small-group sharing events, developing forums for anonymous sharing of P3 lessons learned and “real-life” stories, and documenting best practices.

Others had suggestions for improving the website experience, including keeping documents up to date and organizing the website in a more intuitive way.

A few experienced practitioners noted that the P3 Program and the P3 Toolkit website can be hard to navigate, as it attempts to serve both those new to P3s and practitioners that are more advanced. They notice too many documents and tools falling somewhere in the middle, with documents that are too advanced for beginners but too basic for advanced users. While they admire the effort of trying to create a one-stop P3 resource, they suggest that the program focus on one experience level.

When asked whether there were any suggestions for the P3 Program that could help FHWA staff serve their teams, a variety of challenges as well as suggestions were noted. Many raised the issue of trying to provide materials that applied to the unique situations of the projects in their State. The most common suggestion to remedy this was to provide more real-world examples and documents that pull-out examples and lessons learned from successful, and not so successful, P3 projects.

Several FHWA staff also described problems that came up during projects as the State and regional teams tried to balance the demands of all stakeholders. Staff members were looking for materials that help teams communicate with P3 stakeholders, including State legislators, developers, and the public, allowing them to better handle the political challenges that often accompany P3s.

The P3 Program may be currently serving the role as a source of introductory P3 information, but it is not seen as a “complete resource” for this user group. There is, however, room for the P3 Program to fill information gaps in the form of specific project inputs, more detailed cases, and project documents to increase its value to a P3 advisor.

[1]“States” refers to 35 States as well as the District of Columbia and the territory of Puerto Rico.

[2]State legislative analyst, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team) and Chris Calley (evaluation team), September 2016.

[3]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team) April 2016.

[4]State P3 employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team) May 2016.

[5]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team) and Chris Calley (evaluation team), August 2016.

[6]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[7]A total of 33 States passed official P3-enabling legislation, while Michigan and New York authorized P3 projects without State-level enabling legislation.

[8]P3 Projects considered included those that included design and build components along with at least one long-term program aspect, including finance, operations, or maintenance.

[9]Survey information can be found in appendix B.

[10]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[11]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[12]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[13]State agency employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), April 2016.

[14]Additional survey information can be found in appendix B.

[15]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[16]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[17]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[18]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[19]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[20]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[21]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[22]Additional survey information can be found in appendix B.

[23]Additional survey information can be found in appendix B.

[24]FHWA Employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[25]FHWA Employee, Phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[26]FHWA Employee, Phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[27]Additional survey information can be found in appendix B.

[28]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[29]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[30]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[31]Additional survey information can be found in appendix B.

[32]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[33]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[34]P3 consultant, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team) and Chris Calley (evaluation team), September 2016.

[35]State P3 employee, phone interview conducted by Chris Calley (evaluation team), September 2016.

[36]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team) and Chris Calley (evaluation team), September 2016.

[37]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Chris Calley (evaluation team), September 2016.

[38]State transportation department employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), April 2016.

[39]State transportation department employee, Phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), May 2016.

[40]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin (evaluation team), April 2016.

[41]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin, April 2016.

[42]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin, May 2016.

[43]FHWA employee, phone interview conducted by Lora Chajka-Cadin, April 2016.