U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| TECHBRIEF |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-16-039 Date: June 2016 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-16-039 Date: June 2016 |

PDF Version (300 KB)

PDF files can be viewed with the Acrobat® Reader®

FHWA Publication No.: FHWA-HRT-16-039 FHWA Contact: Ann Do, HRDS-30, (202) 493-3319, ann.do@dot.gov |

The pedestrian hybrid beacon (PHB)—or high-intensity activated crosswalk (HAWK), as it is known in Tucson, AZ—is a traffic control device used at pedestrian crossings that was first included in the 2009 Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD).(1) The treatment typically has the crosswalk marked on only one of the major road approaches. The PHB's vehicular display faces are generally located on mast arms over the major approaches to an intersection and in some locations on the roadside. An example is shown in figure 1 for an installation in Tucson, AZ. The face of the PHB consists of two red indications above a single yellow indication. It rests in a dark mode, but when it is activated by a pedestrian, it first displays to drivers a few seconds of flashing yellow followed by a steady yellow change interval and then displays a "walk" indication to pedestrians and a steady red indication to drivers, which creates a gap for pedestrians to cross the major roadway. During the flashing pedestrian clearance interval, the PHB displays an alternating flashing red indication to allow drivers to proceed after stopping if the pedestrians have cleared their half of the roadway, thereby reducing vehicle delays. Additional information about the PHB is available in the MUTCD.(1)

Figure 1. Photo. Example of PHB installation in Tucson, AZ.

The PHB has shown great potential for improving pedestrian safety and driver yielding.(2, 3) However, questions remain regarding under what roadway conditions—such as crossing distance (i.e., number of lanes) and posted speed limit—should it be considered for use. In addition, there are questions about the device's operations; for example, a current topic of discussion within the profession is the way drivers treat a PHB when it is dark. PHBs dwell in a dark mode for drivers until activated by a pedestrian. A concern within the profession is that drivers will see a dark PHB and treat it as a Stop sign (R1-1), similar to the required behavior for a dark traffic control signal that has experienced a power outage.

Because of the questions being asked regarding driver and pedestrian behaviors with PHBs, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) sponsored a study to record behaviors at existing sites. This TechBrief describes the methodology and results from an open-road study that examined driver and pedestrian behavior at crosswalks with PHBs. The objective of the study was to determine actual driver and pedestrian behaviors at locations with a PHB.

The research team compiled a preliminary list of PHB locations. Data for key variables (i.e., posted speed limit, number of through lanes, and the type of median treatment) were gathered and added to the list of PHBs for communities with multiple installations. Pedestrian crossings on higher speed roadways and with wider crossings have historically experienced lower driver yielding, so posted speed limit and crossing distance (as reflected by number of lanes) were selected as key variables. The cities of Austin, TX, and Tucson, AZ, had the greatest variety in site characteristics of interest to this project and were selected for the study. Roadway and traffic details for the 20 sites included in this study are shown in table 1.

| Site | Con | Legs | PSL | ADT | P/hr | Lanes | PK/BK | MT | MW | CW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TU-003 | INT | 4 | 35 | 7,400 | 4.8 | 4 | NA/6 | TWLTL | 13 | 69 |

| TU-004 | INT | 3 | 40 | 7,600 | 9.3 | 4 | NA/6 | TWLTL | 13 | 82 |

| TU-007 | INT | 3 | 40 | 8,700 | 8.9 | 4 | NA/6 | TWLTL | 13 | 69 |

| TU-021 | INT | 4 | 40 | 31,000 | 8.2 | 4 | NA/5 | TWLTL | 12 | 83 |

| TU-037 | INT | 4 | 35 | 27,500 | 11.1 | 4 | NA/5 | TWLTL | 11 | 75 |

| TU-042 | INT | 4 | 30 | 5,100 | 14.2 | 4 | NA/NA | Raised | 8 | 88 |

| TU-059 | INT | 4 | 40 | 28,400 | 3.1 | 4 | NA/4 | Raised | 8 | 89 |

| TU-070 | INT | 3 | 40 | 29,900 | 3.6 | 4 | NA/4 | Raised | 7 | 80 |

| TU-072a | INT | 4 | 40 | 41,300 | 7.6 | 6 | NA/6 | Raised | 10 | 119 |

| TU-073 | INT | 4 | 40 | 13,800 | 13.3 | 6 | NA/6 | Raised | 8 | 93 |

| TU-090 | INT | 4 | 40 | 10,100 | 1.1 | 4 | NA/7 | Raised | 8 | 92 |

| TU-091 | INT | 3 | 35 | 5,200 | 2.5 | 4 | 13/5 | Raised | 11 | 112 |

| AU-04 | INT | 4 | 35 | 26,600 | 11.5 | 4 | NA/NA | Raised | 10 | 50 |

| AU-07a | MB (50) | 2 | 35 | 24,600 | 23.3 | 4 | NA/NA | Raised | 8 | 57 |

| AU-11 | INT | 3 | 40 | 26,900 | 6.4 | 4 | 8/NA | TWLTL | 12 | 90 |

| AU-16 | INT | 4 | 35 | 28,500 | 18.5 | 4 | NA/NA | TWLTL | 12 | 60 |

| AU-21 | MB (60) | 2 | 35 | 27,100 | 20.0 | 4 | NA/NA | None | NA | 40 |

| AU-22 | MB (70) | 2 | 45 | 19,600 | 38.3 | 4 | NA/6 | TWLTL | 12 | 68 |

| AU-24 | INT | 4 | 35 | 14,100 | 20.7 | 4 | NA/NA | Raised | 6 | 68 |

| AU-27 | MB (80) | 2 | 35 | 21,200 | 10.7 | 4 | NA/6 | Raised | 6 | 80 |

|

aPHB is located within a coordinated signal corridor where the permissive window for PHB display activation is influenced by adjacent signals. |

||||||||||

The crosswalk markings for these sites were always located on only one major street approach. The PHBs had between 3 and 4 s of flashing yellow and between 3 and 4 s of steady yellow. The flashing red duration varied based on the site's crossing width and ranged from 15 to 29s. Table 2 provides other characteristics of the PHBs in Tucson, AZ, and Austin, TX.

| Component | Austin, TX | Tucson, AZ |

|---|---|---|

| Back plates | No | Yes, including reflective yellow borders |

| Sign on mast arm (typically) | CROSSWALK STOP ON RED

(symbolic circular red) STOP ON FLASHING RED (symbolic flashing circular red)

THEN PROCEED IF CLEAR signa |

|

| Sign upstream or at stop line | STOP HERE ON RED (R10-6,

R10-6a) sign at stop line |

Pedestrian Crossing (W11-2)

or School Crossing (S1-1) warning sign on approach |

| Red clearance time | 2 s | 1 s |

| Steady red interval | 9-12 s | 8 s |

|

aFHWA has received numerous inquiries regarding how to address comprehension issues with the flashing red phase and is now recommending that if an alternative legend to the R10-23 sign is used, that it be the sign shown in figure 2. |

||

Figure 2. Photo. Sign (30 by 36 inches) recommended by FHWA to address comprehension issues with the flashing red phase.

Data using a multiple video camera setup were collected in November 2014 for the Austin, TX, sites and February 2015 for the Tucson, AZ, sites. All observations were collected during daytime, dry-weather conditions between 6:30 a.m. and 6:30 p.m. The observers and the video recording devices were placed so as to be inconspicuous to pedestrians, bicyclists, and motorists. The video footage was reviewed in several rounds to extract the required observations for analysis. The final dataset reflected over 78 h of video data and included 1,149 PHB actuations and 1,979 pedestrians crossing.

The videos were reviewed to identify each occurrence when a vehicle stopped at the crossing when the PHB was displaying a dark indication. There were several events; however, in almost all cases, it was because of congestion. There were a few cases where the driver stopped because of a bus or truck loading/unloading or because a pedestrian was in the crosswalk. Therefore, none of the drivers who stopped at the crossing when the PHB was dark appeared to be confused by the device.

For each pedestrian crossing when the PHB was showing steady or flashing red, the number of drivers who yielded and did not yield was determined. A driver was considered to have not yielded to the pedestrian if the driver crossed the crosswalk markings when the PHB was in either the steady red or flashing red indications and the pedestrian was either at the edge of the street clearly communicating the intent to cross or crossing on the same approach as the driver. Table 3 provides the driving yielding values for the 20 sites. Overall, driver yielding for these 20 sites averaged 96percent. In almost all of the crossings, drivers were appropriately yielding to the crossing pedestrians. Overall averages by city shows a potential difference (97 percent for Tucson, AZ, and 94 percent for Austin, TX); however, when site TX‑AU-11 was removed, the driver yielding difference between the cities was nominal (97 percent for Tucson, AZ, and 96 percent for Austin, TX).

| Site | Number of PHB Actuations | Number of Drivers Yielding | Number of Drivers Not Yielding | Driver Yielding (Percent)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TU-003 | 19 | 54 | 3 | 95 |

| TU-004 | 49 | 162 | 4 | 98 |

| TU-007 | 60 | 183 | 5 | 97 |

| TU-021 | 52 | 131 | 7 | 95 |

| TU-037 | 74 | 248 | 8 | 97 |

| TU-042 | 71 | 187 | 6 | 97 |

| TU-059 | 55 | 151 | 0 | 100 |

| TU-070 | 52 | 159 | 4 | 98 |

| TU-072 | 51 | 230 | 5 | 98 |

| TU-073 | 70 | 368 | 19 | 95 |

| TU-090 | 28 | 61 | 0 | 100 |

| TU-091 | 30 | 67 | 4 | 94 |

| AU-04 | 62 | 147 | 9 | 94 |

| AU-07 | 95 | 256 | 11 | 96 |

| AU-11 | 60 | 169 | 26 | 87 |

| AU-16 | 71 | 195 | 6 | 97 |

| AU-21 | 52 | 139 | 5 | 97 |

| AU-22 | 70 | 171 | 4 | 98 |

| AU-24 | 97 | 182 | 9 | 95 |

| AU-27 | 31 | 99 | 10 | 91 |

| Total | 1,149 | 3,359 | 145 | 96 |

|

aDriver yielding = Percent of approaching drivers who should have yielded and did so. |

||||

For about 20 percent of the observed PHB actuations, vehicles were not present during the flashing red indication. When a queue of vehicles was present during the flashing red indication, about half of the actuations included at least one driver who did not completely stop prior to entering the crosswalk.

About 5 percent of the actuations included at least one driver who stopped on the flashing red indication and remained stopped until the dark indication began. In some cases, these drivers might not have realized that they could proceed after stopping if their half of the crosswalk was clear of pedestrians. However, there were many cases where the stopped drivers could not proceed because of the continued presence of pedestrians or minor-movement vehicles that were in the intersection.

Of the 1,979 pedestrians who crossed the street, 290 were research team members who always departed during steady or flashing red and who always activated the PHB. The remaining 1,689 general public pedestrians were coded by whether they pushed the pedestrian pushbutton or did not push the pushbutton subdivided by whether the PHB was already active or not active when they arrived at the crossing. Overall, most pedestrians (average of 91 percent) who could have activated the PHB did. A review of the data shows trends for the highest values. A high number of pedestrians (93 percent) activated the device on the 45-mi/h posted speed limit road. For the 40-mi/h or less roads, a large range of actuation was observed (between 75 and 100 percent).

The 1-min volume count nearest to the arrival time of each pedestrian was determined. The number of pedestrians by their action was summed for each 1-min count value for all 20 sites. When the hourly volume for both approaches was 1,500 vehicles/h or more, the percent of pedestrians activating the PHB was always 92 percent or more.

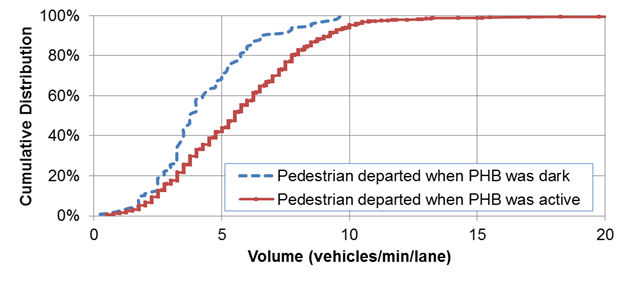

For the pedestrian crossings observed, only 124 of the 1,689 general public pedestrians (7percent) left during the dark indication. For the majority of these pedestrians, the roadway volume was such that the pedestrians were able to find sufficient gaps to cross (volume was less than 4vehicles/min/lane for the majority of these crossings). Figure 3 shows the cumulative distributions of the 1-min/lane volume for those pedestrians that departed during the dark phase (blue dashed line) and those that departed during an active phase (red solid line). Pedestrians were more likely to wait for the PHB to be active before starting to cross at the higher roadway volumes, as shown by the location of the red solid line to the right of the blue dashed line.

Figure 3. Graph. Volume cumulative distribution when pedestrian started.

All occurrences of pedestrian/vehicle conflicts and erratic maneuvers were noted when observed in the video footage. In the 78 h of video footage, 54 conflicts were observed. The conflict rate was found to be higher for noncompliant pedestrians than for compliant pedestrians. Slightly less than half of the observed conflicts occurred during the dark beacon indication and involved a through vehicle. These conflicts usually involved pedestrians who either crossed without pushing the button or pushed the button but did not wait for their walk indication and then paused on the raised-curb median while crossing.

Notable conflict rates for both compliant and noncompliant pedestrians were observed at several sites where the PHBs were located near supermarkets and multiple bus stops. At these sites, many bus riders would walk through the supermarket parking lots or run across the major street while transferring between bus lines. The presence of bus stops near an access point with significant turning vehicle volumes tended to result in higher conflict rates.

The PHB has shown great potential in improving safety.(2) It is also associated with fewer delays for the major roadway as compared with a full traffic control signal because of the PHB's flashing red indication that permits stop-and-go operations if the pedestrians have finished crossing their half of the roadway. A total of 20 locations in Tucson, AZ, and Austin TX, were selected for inclusion in this study, representing a range of posted speed limits, different median types, and major roadways with four and six lanes. The final dataset reflected over 78 h of video data and included 1,149PHB actuations and 1,979 pedestrians crossing.

Most of the observed conflicts were associated with noncompliant pedestrians. Several conflicts were observed at a site with a nearby access point (e.g., driveway), which could indicate that access points should be limited within a certain distance to the PHB, especially if they serve major traffic generators. Additional research is needed to determine the distance(s) at which access points should be restricted. The research should also consider the type of access point or the anticipated volume from the access point, as well as proximity to bus stops where pedestrians may be making transfers between bus lines.

None of the drivers appeared to be confused regarding the PHB device when it was dark. That is, they did not regard the dark PHB as requiring a stop. Drivers stopped at a dark PHB because of a queue from downstream congestion or a crossing pedestrian who did not activate the PHB.

For the pedestrian crossings observed, only 124 of the 1,689 pedestrians (7 percent) departed during a dark indication. For the majority of these pedestrians, the roadway volume was such that the pedestrian was able to find sufficient gaps to cross. Overall, 91 percent of the pedestrians pushed the button and activated the PHB.

Driver yielding for the 20 sites averaged 96 percent. In almost all of the crossings, drivers appropriately yielded to the crossing pedestrians. The study identified high driver yielding for the two sites with the widest crossing (94 or 98 percent) and the site with the 45-mi/h posted speed limit (greater than 98 percent). The findings from previous studies and the overall high yielding for PHBs identified in this research supports the use of this device at a variety of locations, including on high-speed and wide roads, at residential intersections, and elsewhere. (See references 3 through 6.)

Researchers—This study was performed by Principal Investigator Kay Fitzpatrick along with Michael Pratt. For more information about this research, contact Dr. Kay Fitzpatrick, Texas A&M Transportation Institute, 2935 Research Parkway, College Station, TX 77845-3135, k-fitzpatrick@tamu.edu. Distribution—This TechBrief is being distributed according to a standard distribution. Direct distribution is being made to the Divisions and Resource Center. Availability—This TechBrief may be obtained from the FHWA Product Distribution Center by e-mail to report.center@dot.gov, fax to (814) 239-2156, phone to (814) 239-1160, or online at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/research. Key Words—Pedestrian hybrid beacon, HAWK pedestrian crossing, pedestrian crossing, driver yielding to pedestrians, pedestrian and driver behaviors. Notice—This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers' names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document. Quality Assurance Statement—The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides high-quality information to serve the Government, industry, and public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. |