U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-16-059 Date: November 2017 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-16-059 Date: November 2017 |

The project consisted of two experimental tasks. The first task was a laboratory-based experiment in which participants were presented with scenarios and video of ATT displays and then were asked to provide ratings and to offer location recommendations. The second task was a field implementation over 11 weeks investigating behavior, ratings, and use of both freeway and ATT information provided near a freeway entrance approach. Information was provided via CMS and in-vehicle. A main goal of both studies was to better understand optimal ways and preferred locations for presenting both freeway and ATT information to commuters.

Study 1 investigated options for presenting nonfreeway-based travel time information using a laboratory-based experiment. This section describes the methods and results.

This subsection describes the design, participants, and procedure used for study 1.

Design

The laboratory task was a within-subjects design with one group of commuters. Sign message content and scenario were manipulated throughout the task. In addition, participants provided ratings, qualitative responses, and sign location mapping preference.

The key dependent variables in this study were the following:

Participants

There were a total of 51 participants for the laboratory study. All participants were licensed drivers from the Washington, DC, metropolitan area who were regular commuters on the I-270 corridor. There were no freeway or ATT signs on this corridor. All participants lived in the vicinity of Germantown, MD, and therefore were familiar with the I-270 interchanges in the area. When surveyed, on average, participants reported that 94.24 percent of their morning commute trips were via I-270. Participants received $75 compensation for participation in the study.

All sessions took place in the research team’s computer laboratory. Sessions were run in groups of up to 15 participants at a time and lasted between 1.5 and 2 h. Each participant was seated at a computer terminal. The experiment had four parts.

Procedure

At the beginning of the session, participants were given background information about travel time signs. The experimenter then gave a brief overview of the purpose of the study and the tasks the participants would be performing. Next, the experimenter walked the participants through practice trials of the computer task for part 1 of the study. After the practice trials, the experimenter answered any questions about the task.

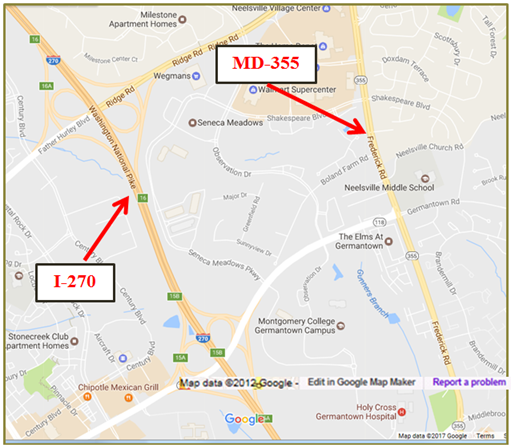

After the practice trials, participants moved on to part 1 of the study, which was a self-paced computer-based procedure in which a computer display placed participants in a familiar commuting situation and presented various scenarios regarding traffic and travel time messages. This was done through the use of video clips and displays presented to the participants via their computer monitor. For each trial of the procedure, the participant was placed in a defined scenario. Scenario variables included participants’ current location (on an arterial approach to I-270 or already on I-270), destination (participants’ actual workplace or Shady Grove Metro station), and traffic conditions (free flow, moderate traffic, heavy traffic). In cases where travel time was provided via both I-270 and an arterial alternative (Route 355), traffic conditions could vary between the two routes. The scenario was defined by a written description and a brief video clip showing the current traffic condition at the actual location the participants were to imagine that they were located. The video allowed a participant to have a realistic perception of the immediate speed and traffic conditions. Figure 2 shows an example of a map participants were shown to indicate their current location. Figure 3 shows such a description and still from the video clip presented to participants in the laboratory study. The scenario is on Route 355.

©2017 Google®; map annotations made by the research team.

Figure 2. Map. Participants’ current locations in the hypothetical scenario.(17)

After the scenario was defined, a travel time display was presented on the screen. Participants were instructed to click a mouse button as soon as they felt they had acquired the relevant information. In addition to travel time signs, a few signs with no travel time information were presented as baseline measures. These signs included information such as Amber alerts, road work signs, silver alerts, etc. The time to process the display was recorded. Once the mouse click occurred, the travel time display disappeared, and three 10-point rating scales appeared (see figure 4). Participants rated the display in terms of subjective ease of use, their willingness to divert to another route, and confidence in their knowledge of the best route.

Part 2 of the study began with the participant being shown an area map on a projector screen. Participants were asked to imagine that they were driving south on Route 355, approaching Route 118. On their computer monitors, a series of travel signs were presented. For each sign, they indicated whether they thought that the posted travel time via I-270 was calculated for the current location on Route 355 or from the I-270 entrance ramp. This task investigated participants’ understanding of whether the travel time information included travel time from the current location to I-270 or just travel time on I-270. Each travel time display included different wording and/or formatting. Some displays were intended to suggest from what location the travel time was calculated, while others were ambiguous. After selecting an answer, participants rated how confident they were that their answer was correct. Eleven signs were presented to the participants in this part of the study. Figure 5 through figure 16 show the 12signs used in this portion of the study. Note that figure 8 and figure 9 contain phases 1 and 2, respectively, of stimulus 4. The results of this task were intended to help traffic engineers to choose a sign format that most effectively displayed information to drivers.

For part 3 of the experiment, participants were given one of two sets of pictures of different signs displaying travel time information. Set 1 had signs that showed travel time via I-270, and set2had signs that showed travel times via both I-270 and Route 355. Participants viewed either set 1 or set 2. Participants were told to imagine that these signs would be shown on an arterial approach to I-270. Their task was to rank their top five favorite signs in order of preference by writing the number on the sign on the answer sheet. Participants were then asked to write an explanation of why they thought the sign they rated as number one was the best.

For the final part of the experiment, participants were provided with a personalized map of the area around where their morning commute began. This information was obtained during the telephone screening for participation. On the personalized map, the area where their morning commute began was marked with a red circle. Participants were asked to use a highlighter to trace the route they took most often to work in the morning. The experimenter then asked participants to think about where on their commute route they thought a travel time sign would be most useful and what the sign would look like. They were then asked to use a pen to mark an X on the map where they would like the sign to be but were instructed that the X should not be placed on I-270 or any other freeway. After choosing the location, they were asked to use the blank space on the map to write the message they would like to see on the sign.

After the final part was completed, the experimenter collected all materials and paid the participants, and the session ended.

The following subsections describe the results of the main computer task, the sign location task, the route choice factors questions, and personalized map sign location task.

Main Computer Task

The following results section is divided into key comparisons of certain sign features. All of the sections follow the same format. First, brief information about the importance of the comparison is given. Then, a table shows the sign number (a combination of group and sign, e.g., “3-2” is group 3, sign 2), an image of the actual display, the location of the sign, the percentage of participants who said they would continue their current route (e.g., the sign would not change their plan), the average rating of confidence in their knowledge to make the best choice, the average rating of ease of use of sign, and the average rating of their willingness to divert to another route. Ratings for confidence in knowledge to make best decision, ease of use, and willingness to divert to another route were made on a scale of 1 to 10 with 1 meaning not confident at all, very difficult, and definitely would not change route, respectively, and 10 meaning extremely confident, very easy, and definitely would change route, respectively. Following the table is a brief synopsis of the data presented in the table.

Effect of Arterial Location Versus Freeway Location

One of the main goals of this study was to examine whether receiving travel time information on an arterial versus on a freeway resulted in behavior change among drivers, particularly in willingness to divert route. Participants were shown the same sign with one key difference: they were told that one sign was located on I-270, and the other sign was located on an arterial (MD Route 355). Table 2 shows the results.

Comparing these two signs revealed that participants’ ratings of confidence in knowledge of best route, ease of use, and willingness to divert to another route were relatively the same regardless of the location of the sign. However, table 2 revealed that when presented with travel time information while on I-270, 86 percent of people would continue driving on I-270. However, when presented with this information on an arterial road, 76 percent of people would continue on to I-270. This 10-percent difference in willingness to drive on the highway indicates that when presented with a travel time sign on an arterial roadway, more people would consider alternate routes to the freeway than if they were already on the freeway when they received that information. This finding suggests that drivers are more willing to take an alternate route before they have committed to the freeway route.

Effect of Receiving Freeway-Only Information Versus Freeway and Arterial Information

Travel time signs displaying information about just one location may not provide drivers with enough information to divert their route. The research team presented drivers with a sign showing two destinations both via I-270 (only one route option) and another sign with travel time information to an arterial destination via I-270 and an arterial route (two route options). Comparing these two signs provided insights into drivers’ preferences for CMS travel time displays (see table 3).

Avg. = average.

These data indicate that when given more information (i.e., travel time information about both a freeway and an arterial), drivers are more likely to stay on their current route when it is an arterial. In other words, drivers who receive only information via a freeway route are more likely to divert and continue onto the highway, which may be potentially congested. In addition, drivers had higher ratings in confidence of knowledge of best route, ease of use, and willingness to divert when given more information (two potential routes).

Effect of Receiving Freeway-Only Information Versus Freeway and Arterial Information for a Metro Location

The previously discussed effect of freeway-only versus freeway plus arterial information may be confounded by the fact that all participants were imagining driving on their morning commute to work, which varied among participants. Therefore, the same comparison can be made by looking at data when similar signs were presented and all drivers were asked to imagine that the Shady Grove Metro station was their final location (see table 4).

These data show a similar pattern as that shown in table 3; however, the percentage of people staying on the same route is markedly increased in the Metro destination scenario. In the case with a Metro destination, there is an increase of 32 percentage points of people who would stay on the arterial route if given information about both the freeway and the ATT rather than just FTT (compared with 8 percentage points more in the work destination scenario). In addition, the average confidence in knowledge to choose the best route and willingness to divert route were higher for the freeway plus ATT sign, and average ease of use was the same as for the freeway-only sign.

Effect of Color Coding Times

Some of the signs presented to participants during the laboratory study were color coded with red indicating bad traffic and green indicating lighter traffic. Signs with the same information about destination and travel time were presented with different color-coding options. See table 5 for results.

1On the display, “22 MIN” shows in green lights.

2On the display, “32 MIN” shows in red lights.

The data indicated no significant differences between drivers on an arterial (Route 355) receiving color-coded travel time information about that arterial versus non-color-coded travel time information. However, when presented with color-coded travel time information about a freeway while on an arterial versus non-color-coded information, 16 percent more drivers would stay on their current route (the arterial). It appears possible that color coding has the greatest effect when drivers cannot visually confirm traffic conditions (e.g., on a roadway other than the one they are currently traveling).

Effect of Supplemental Information

Another variation in CMSs rated by participants was the addition of different types of supplemental information. For example, some of the travel time signs displayed average speed information or distance to location. Others included information about incidents and delays or travel alerts. It is possible that receiving additional information other than travel time may affect drivers’ behaviors. See table 6 for results.

The first three signs in table 6 displayed similar information, but the first sign exclusively displayed travel time, the second sign included average speed information, and the third sign included distance information. It seems as though having information about average speed, in addition to travel time, is useful for drivers. Compared with 24 percent for travel time only and 28 percent for distance and travel time information, 49 percent of participants said they would stay the same route when provided with travel time plus average speed information. It is possible that 30 mi/h is a clearer indication of traffic conditions than a travel time that reflects the same information. When general “expect delays” information was added to the travel time signs, 60percent of participants reported that they would stay on Route 355. When this same information was provided as a second phase and an incident location was added, the participants reporting that they would stay on Route 355 dropped from 60 to 40 percent. The reason for this drop is unclear, but it could be that when drivers knew where an incident occurred, they realized that traffic should be clear beyond that location (congestion not indefinite).

Effect of Alternative Formats

Alternate sign formats were also tested in this study. The types of sign formats were the trailblazer sign, diagrammatic sign, and “hybrid” sign (sign 9-3, sign 2-3, and sign 9-1, respectively). Regular sign formats and these alternative sign formats with the same information can be compared with each other in figure 17 through figure 24. Correspondingly, table 7 through table 13 indicate participant responses to each sign type.

| Sign Number | Location of Display | Percent Stay Same Route | Average Confidence | Average Ease of Use | Average Willingness to Divert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9-2 | Arterial | 82 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 9.1 |

| Sign Number | Location of Display | Percent Stay Same Route | Average Confidence | Average Ease of Use | Average Willingness to Divert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9-1 | Arterial | 82 | 9.1 | 9.3 | 9.4 |

| Sign Number | Location of Display | Percent Stay Same Route | Average Confidence | Average Ease of Use | Average Willingness to Divert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9-3 | Arterial | 68 | 8.6 | 7.5 | 8.3 |

| Sign Number | Location of Display | Percent Stay Same Route | Average Confidence | Average Ease of Use | Average Willingness to Divert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-5 | Arterial | 24 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 8.4 |

| Sign Number | Location of Display | Percent Stay Same Route | Average Confidence | Average Ease of Use | Average Willingness to Divert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-3 | Arterial | 30 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 8.2 |

| Sign Number | Location of Display | Percent Stay Same Route | Average Confidence | Average Ease of Use | Average Willingness to Divert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-4 | Arterial | 32 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 8.8 |

| Sign Number | Location of Display | Percent Stay Same Route | Average Confidence | Average Ease of Use | Average Willingness to Divert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-5 | Arterial | 44 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 8.7 |

Figure 18 depicts sign number 9-1, a hybrid-type sign. The hybrid sign format received the highest ratings on confidence in knowledge to make the best decision, ease of use, and willingness to divert to another route. This is compared with the trailblazer formatted sign, which received the lowest ease of use rating (7.5). Based on the ratings for different sign formats, it seems that participants preferred the “hybrid” sign as a means for receiving travel time information.

Figure 24 summarizes participant ratings on confidence in knowledge to make the best decision, ease of use of signs, and willingness to divert to another route for all signs presented during this experiment. This graph shows that participants generally rated all signs similarly, between about 8 and 9, on confidence in knowledge to take the best route, ease of use, and willingness to divert to another route. Several signs did deviate in terms of having slightly different ratings. For instance, sign 5-1 was rated much lower on willingness to divert to another route. This sign was presented in a scenario in which participants were told they were driving to the Metro. This specific and fixed destination may have contributed to the lower rating of willingness to divert to another route. In addition, sign 3-2 had lower ratings on willingness to divert to another route and ease of use. This was a two-phased sign, which may have caused difficulty in ease. One sign with overall higher ratings than most of the others was sign 18-1. This sign was an arterial-based sign displaying travel time information about both an arterial and a freeway. In this instance, the freeway had heavy traffic, and the arterial had light traffic. This contrast of travel time conditions could have contributed to the higher ratings.

Conf = confidence.

Figure 24. Chart. Average confidence, ease of use, and willingness to divert ratings for all signs. The asterisk denotes a 2-phased sign.

Sign Location Task

During part 2 of the study, participants were asked to imagine that they were driving south on Route 355, approaching Route 118. On their computer monitors, a series of travel signs was presented. For each sign, they indicated whether they thought that the posted travel time via I-270 was calculated for the current location on Route 355 or from the I-270 entrance ramp. Twenty-six percent of participants thought that the default freeway-only sign was calculated from the sign location. However, 64 percent of participants thought that the default freeway plus arterial information sign’s I-270 travel time was calculated from the current location. Therefore, the mental models for freeway-only and freeway plus ATT may be different. The two freeway-only signs that were most explicit that travel time was calculated from the ramp had 6 and 16 percent of participants say it was calculated from the current location. The freeway plus ATT sign that was explicit still had 44 percent report it was calculated from current location, suggesting that the mental model in this case may be hard to overcome. Among other signs, the percentage of participants who said the travel time was calculated from the current location varied from 22 to 52 percent, suggesting that most sign formats lacking explicit statements cause confusion to a significant portion of drivers.

Route Choice Factors Questions

Before each session, participants filled out a survey about route choices that they made on their morning commute. They received the following instructions:

Below you will find a list of statements about factors that might influence your route choice during your morning commute. Please rate each factor’s role in your route choice decision for your morning commute. Make your ratings on a scale of one to seven, where one means “strongly disagree,” where four means “neutral” or “no opinion.,” and seven means “strongly agree.” If any factors that influence your morning commute route are not listed below, please write them in at the bottom of the list.

Table 14 shows the survey questions and the mean rating of participants for each.

Personalized Map Sign Location Task

For the last portion of the laboratory study, participants were given a personalized map of their daily commute and asked to indicate the location where they would most want a travel time sign to be displayed. In addition, they drew an image of what they would like this sign to look like. These data were entered into a database and coded based on the following characteristics: sign placement (number of alternatives before the freeway); use of color; design (graphical versus text-based); phases; presence of time, average speed and/or distance information; presence of delay information (general versus specific location); number of destinations; what destinations; and travel time via what roadways. Based on an analysis of these personalized signs, several characteristics stood out as most desired among drivers (i.e., features that had much higher frequencies than others).

Sign Placement

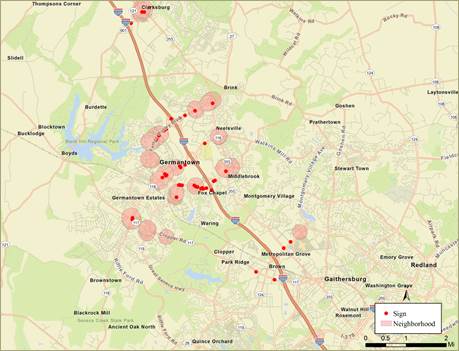

During the screening procedure for recruitment, participants’ home addresses were collected. During the personalized map portion of the study, they received a map with a red circle indicating their home neighborhood. Figure 25 uses ArcGIS™ software to display participant neighborhoods and the locations where they placed their personalized signs.

Figure 25. Map. ArcGIS™ map illustrates neighborhoods of participants and location of personalized signs.

The red dots on the map indicate sign placement. A cluster of red dots around the final approaches to I-270 is evident from figure 26. Only two participants placed the sign on the freeway. In addition, during the coding of the personalized CMS signs, sign placement was coded as the number of alternatives to the freeway still available. The coded data can be seen in figure 26.

Considered together, these data indicate that CMS displays of travel time may be most valuable to drivers on their final approaches to the freeway. As the number of alternative routes decreased, participants’ desire for travel time signs increased. The majority of participants placed their personalized signs on the final approach to I-270 (31 participants), and another 15participants placed their signs in a location where only one alternative existed. It is important to note that only two participants placed their sign on I-270. It seems that people want travel time information at a vital decision point in their drive and would prefer to see it on an arterial when approaching the freeway rather than on a freeway.

Additional geographical analysis was performed using population density by census block data. In figure 27, darker areas indicate more densely populated areas, and lighter areas are less densely populated areas. Overlaid on the population density map are the desired sign locations indicated by the participants.

Figure 28 shows that the personally optimal sign location is not necessarily in the most densely populated areas; rather, the participants’ optimal sign location is clustered around entryways to the freeway.

Another geographical analysis demonstrated potential optimal routes to I-270. ArcGIS™ software was used, and as with other mapping software, it creates heuristic routing options. Figure 28 is a map of these optimal routes.

This map shows that the signs were not placed in typical optimally calculated routes. The research team does not know why this pattern of sign placement along a route other than the optimal route occurred. It is possible that participants reroute because they have another stop along their route during their morning commute, such as dropping a child off at school or carpooling. In addition, it could be that by driving on a “sub-optimal” route, they are able to drive toward areas with more alternative routes to the freeway; therefore, CMS travel time displays along these locations would allow them to make the best choice of their alternative routes.

A final analysis of distance of sign placement (in mi) from the freeway was calculated. On average, participants indicated that they would like CMS travel time signs to be placed 0.594 mi from the freeway. These data reinforce the idea that drivers want CMS signs to be located near their decision points for getting on the highway rather than early in their driving route (prior to the freeway approaches) or on the freeway itself.

Use of Color

Personalized signs were coded for use of color. A total of eight participants indicated that they would prefer any color coding (red, yellow, green, or highlighted) on their sign. This is not a large portion of participants, so it seems that color coding may not be optimal for design or that drivers do not find color coding to be particularly useful.

Graphical Versus Text-Based Design

The vast majority of participants’ personalized signs were text-based rather than graphically based. Forty-three participants drew travel time signs that were text based compared with only 6 participants who drew graphically based signs. Text-based signs may be easier for drivers to process and may be more streamlined than graphically based signs.

Phases

CMS displays can be either one- or two-phased. Thirty-three participants drew one-phased signs, and 11 participants drew two-phased signs. Interestingly, many of the participants who drew a two-phased sign indicated that phase one would provide travel time information and that phase two would display information about delays/incidents.

Types of Information

CMS displays can include many different types of information, including travel time, average speed, distance, and information about delays and incidents on the roadway. Participants’ personalized signs were coded for these different features. These features do not necessarily need to be independent of each other; CMS displays can include several of these information features at one time. Figure 29 shows types of information on personalized CMS signs.

The data indicate that travel time (in min) is the most desired information on these CMS displays. Relatively few participants included average speed or distance information on their personalized CMS displays. In terms of displaying information about delays and incidents, more participants indicated that they wanted general information versus specific location information.

Destination Information:

The personalized CMS displays that participants drew provided travel time for different numbers and types of destinations. Some people indicated travel time to only one destination, while others indicated travel time to more than three destinations. Figure 30 shows a simple breakdown of the number of destinations people indicated and the actual location of these destinations.

Overall, it was evident that information regarding destination is highly variable among participants depending on their own personal commute or desired destination. Some interesting notes about destinations are that other than I-495, Shady Grove Road, 370, 118, and Montrose Road, participants listed other relevant destinations, including the Inter-County Connector, specific exits along the highway (e.g., Exit 8), or more local roads near their neighborhoods. These data further emphasized the specificity that participants had in mind while creating these CMS displays. In addition, many participants specifically stated that they wanted travel time information for the I-270 split or the I-495 spur, particular areas of traffic congestion locally. While congestion areas vary from region to region, the fact that participants specifically cited these two areas has important implications; people may most want information about the worst traffic areas.

In addition, participants indicated that they would like their CMS displays to reflect travel time information via a particular type of roadway—either freeway (I-270) or arterial (Route 355). The coded data for this feature of the personalized signs is shown in figure 31.

Most participants wanted their travel time to be reflective of whether they were driving on a freeway. However, a high number of participants also drew signs that included both arterial and freeway routes. Only one participant indicated travel time via only an arterial roadway. These data indicate that information about the freeway is most important to drivers.

Study 2 investigated actual commuter experience with alternative practices of travel time displays using field implementation and evaluation. This section describes the methods and results.

This subsection describes the design, location selection, equipment, participants, and procedure used for study 2.

Design

The field evaluation was conducted with a before/after assessment on an experimental site. Participants were not provided with any travel time information during the pre-implementation stage but were provided with both arterial (via in-vehicle device) and freeway (via roadway sign) travel time following implementation.

The key dependent variables in this study were the following:

Location Selection

The key comparison of interest in this study was whether arterial-based travel time signing improves driver decisionmaking. The following criteria were used to choose location:

The final sign location was selected from the following set:

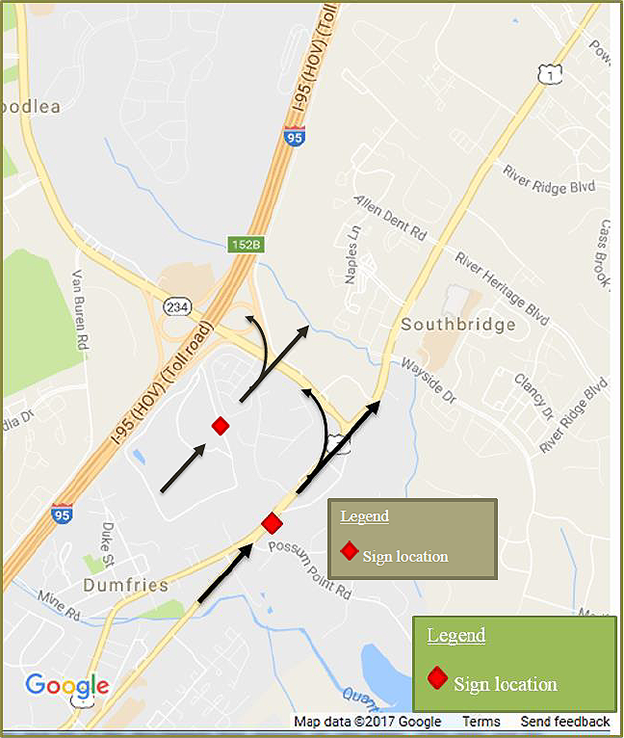

Based on the criteria listed above, the primary candidate for the final site chosen to implement the sign for the study was the CMS 1720 (Richmond Highway). Specifically, the sign was implemented along US-1N (Richmond Highway—CMS 1720), before VA 234. See figure 32 through figure 34.

©2017 Google®; map annotations by the research team.

Figure 32. Map. Field implementation sign location (latitude: 38.5717, longitude: –77.3173).(18)

Equipment

The in-vehicle display and GPS tracking devices were Nexus™ 5, Android™ 4.4.4 cellular telephones using KitKat®.

Features of the devices included the following:

Data logging details include the following:

Figure 35 shows an example of an in-vehicle display.

Participants

A total of 30 paid individuals participated in this field study. All participants were licensed drivers from the Washington, DC, metropolitan area who were regular commuters on US-1N and the I-95 corridor. All participants lived in the vicinity of Dumfries, VA, and were familiar with the I-95 interchanges in the area. Participants were selected who commuted at least 4 days a week and reported alternating use of I-95 and US-1N at least some of the time. They had to commute between 6:00 and 10:00 a.m., heading northbound on US-1N to or beyond RTE 234 (Dumfries) for at least part of their normal commute. Participants were 21 to 55 years old, and the sample was approximately balanced across age decades and genders.

Participants were recruited through the following variety of methods:

Ads stated that commuters were needed for a traffic study but did not state that the study focused on travel time signs (see appendix A). Participants received $200 compensation for completion of the study. In addition, recruitment websites were set up for participants to find relevant information and appropriate contacts.

Procedure

Field implementation for this study was completed in two phases spanning 11 on-task weeks total, with a 2-week break period between the phases. The first phase of the study spanned 2weeks of pre-implementation, in which participants were not presented with any travel time information. In the post-implementation phase, participants were given travel time information in-vehicle via mobile device as well as on the CMS.

Once participants were screened, they received mailed packages containing information about the study as well as instructions for completing the study. Participants were instructed to set up the travel time device as well as to complete trip logs online twice a week (every Tuesday and Wednesday) during each phase. The first 2 weeks of the study, comprising phase 1, started December 8, 2014, and ended December 19, 2014. In this phase, participants did not receive any travel time information from the device or the CMS except for a daily reminder at the end of their commute to fill out trip log surveys. There was a break between December 20, 2014, and January4, 2015. This break was to avoid data collection during unusual holiday traffic patterns. Phase 2 began January 5 and ended February 20, 2015. During this phase, travel time information for a segment of their commute along US-1N was presented in-vehicle through a travel time display device as well as the CMS. Table 15 summarizes pre- and post-implementation activities.

Driver trip logs and questionnaires were used to subjectively assess driver decisionmaking. Specifically, the driver trip logs were used to measure route diversion and route choice. In addition, driver decisionmaking was objectively measured through GPS. GPS location monitoring (with no display) was recorded. (See Equipment section earlier in this chapter for equipment and data logging details.)

The study had three main components. First, participants were tracked with GPS via the in-vehicle devices that were used to display messages. Second, participants filled out online travel logs every Tuesday and Wednesday during the study. Finally, there was an overall travel log at the end of the study.

The results are separated into each of these three sections with particular questions or points of interest highlighted and discussed.

GPS Data and Location Tracking

Route Choice

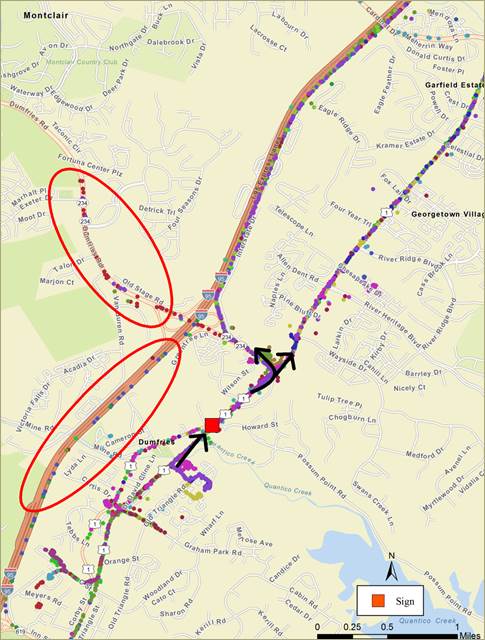

Participants were tracked with GPS-enabled telephones throughout the study. This allowed for a count of trips taken along I-95 and US-1N. Figure 36 displays the individual GPS points collected along the corridor and highlights the ineligible trips because participants did not travel through the corridor and along decision points of interest. Figure 37 displays the percentage of trips for participants along I-95 and US-1N. Note that the proportions do not total 100 because not all trips went far enough beyond the corridor of interest to qualify for the I-95 or US-1N category for this graph.

Figure 36. Map. ArcGIS™ map identifies GPS data points, including eligible (along US-1N and I-95) and ineligible trips (red circles).

Traveler Logs

Participants completed brief traveler logs on Tuesday and Wednesday of each week of the study. There were 2 weeks (i.e., four traveler logs) in the pre-implementation phase of the study and 7weeks for the post-implementation phase (i.e., 14 traveler logs). Responses described are percentages of all responses for a given question.

Pre-Trip Information Sources

Figure 38 shows the distribution of responses when participants were asked the following question: “From what sources of information did you receive traveler information before starting the trip?” These included all responses, even if participants ultimately decided not to travel that day.

The majority of responses indicated participants did not receive any traveler information before beginning a trip (30 and 29 percent for pre-implementation and post-implementation, respectively). TV, radio, and smartphone app were the remaining popular responses. Very few travelers reported using a GPS, social media app, 511, family/friends, or other. The distribution of responses was similar during the pre-implementation and post implementation phases.

If individuals who chose not to travel on a particular day (which could have been the result of prior plans or new information received prior to the trip) were excluded, the distribution of responses was largely unchanged (see figure 39).

En Route Travel Time Information Sources

Figure 40 shows the distribution of responses when participants were asked the following question: “From what sources of information did you receive traveler information during the trip?” These responses include all participant trips, even if they did not pass directly by the sign. This information is still valuable because it reveals their overall trip patterns and usage of information sources. TV, radio, and smartphone apps were the most common responses, in addition to not receiving travel time information at all.

The majority of responses indicated participants did not receive any traveler information during a trip in the pre-implementation stage (34 percent). As expected, this number dropped drastically during the implementation phase of the study (17 percent).

A main question of this study was whether people would be aware of roadside and in-vehicle traveler information. Participants would receive roadside traveler information and in-vehicle traveler information if they passed by the researchers’ study sign on US-1N, as described in the Methods section. Limiting reported sources to only trips that passed by the study sign showed a similar distribution of sources in both the pre- and the post-implementation phases (see figure 41).

Influence on Route Choice

Participants were asked to provide agreement ratings on whether the traveler information on the sign and on the in-vehicle device influenced their trips. A scale from 1 to 5 was used with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Figure 42 shows mean agreement ratings for only actual trips that passed through the corridor of interest during the post-implementation phase. A Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test [1] indicated that the influence roadside travel time information was rated significantly higher than device travel time information, Z = −3.30, p < .005.

Participants agreed that the roadside travel time sign influenced their route choice. As a reminder, the roadside travel time sign provided FTTs. In contrast, the information provided by the in-vehicle device had minimal impact on travelers’ reported route choices. (In-vehicle information was only ATT.)

Usefulness

Participants were asked to provide agreement ratings on whether the traveler information on the sign and on the in-vehicle device was useful. A scale from 1 to 5 was used with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Figure 43 shows mean agreement ratings for only actual trips that passed through the corridor of interest during the post-implementation phase. A Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test indicated that usefulness of device travel time information was rated significantly higher than roadside travel time information, Z = −3.51, p < .001.

Participants rated the in-vehicle device (ATT information) as more useful. The roadside travel time information (FTT information) was also considered useful to the participants but only slightly above the scale midpoint.

Confidence

Participants were asked to provide agreement ratings on their confidence about the travel time information accuracy and whether they made the best decision for their route. A scale from 1 to 5 was used with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Figure 44 shows mean agreement ratings for only actual trips that passed through the corridor of interest during the post-implementation phase. A Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test indicated confidence in the device travel time information was rated significantly higher than roadside travel time information, Z = −3.04, p < .005. In contrast, there was not a significant difference between roadside travel time information and device travel time information with respect to confidence in decisions, Z = −.24, p > .05.

Overall, participants were not particularly confident in either the accuracy of the travel time information (from both the sign and the in-vehicle device) or their decisionmaking.

Ease of Understanding and Overall Likeability

Participants were asked to provide agreement ratings on their ease of understanding the travel time information and their overall likeability regarding travel time information from both devices. A scale from 1 to 5 was used where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Figure 45 shows mean ease-of-understanding ratings and mean overall likeability ratings for only actual trips that passed through the corridor of interest during the post-implementation phase. A Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test indicated that ease-of-understanding device travel time information was rated significantly higher than roadside travel time information, Z = −2.50, p < .05. Similarly, overall likeability of the device travel time information was rated significantly higher than the roadside travel time information, Z = −4.92, p < .001.

The ease-of-understanding ratings showed that participants had difficulty understanding both the roadway sign and the in-vehicle device. This may be because the format that VDOT uses for travel time information does not follow guidance from earlier work that showed certain formats are easier to process (see Lerner et al.).(1) Participants were more favorable to having travel time information provided by the in-vehicle device rather than via a roadside sign, but neither rating was particularly high.

All participants completed a final questionnaire at the end of the study. As with the weekly logs, participants provided ratings of confidence, ease of understanding, likeability, and influence for the overall study duration (not 1 particular week). A scale of 1 to 5 was used where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Figure 46 shows the average ratings on these dimensions.

Not surprisingly, the patterns were similar to those of the weekly travel logs. Participants reported travel time information from the roadway sign and the in-vehicle device was useful and influenced their route decisions. They also reported liking the in-vehicle device more than the roadway sign for travel time information. Neither source was considered easy to understand, although participants had favorable comments about the presentation of the information in general. Interestingly, confidence was lower than the weekly logs.

When asked about usefulness ratings for both the roadway sign and the in-vehicle device, participants often cited accuracy as a reason. One participant who believed the roadside sign was the most useful said, “It was accurate, and I didn’t have to pull up an app on my phone,” while another who also chose the sign said the information provided was “on time.” When considering both the sign and the device together, one participant said, “The sign was accurate, which helped me make a decision on my route,” while another participant reported that the “info provided on both seemed to be accurate.”

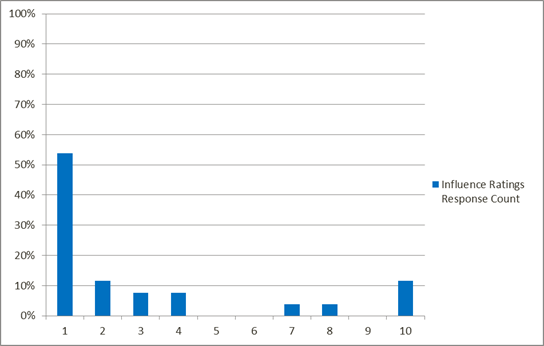

Participants were asked how often the combination of the roadside sign and the in-vehicle device influenced their route choice over the course of the study. The ratings were done on a scale of 1to 10 where 1 = never influenced and 10 = always influenced. Figure 47 presents the proportion of responses for each category of influence, ranging from never influenced (1) to always influenced (10).

Figure 47. Chart. Mean percentage of responses of each influence rating for combination information.

In what may be indicative of the roadway options along I-95 and US-1N, 54 percent of participants reported never being influenced by the travel time information provided by both the roadside sign and the in-vehicle device. Several qualitative comments indicated hopelessness in finding alternative routes and continuously congested traffic. There were not enough variable travel time data points matched with reported influence ratings by day to analyze conditional influence ratings based on congestion levels, which could have yielded additional insights into influence and diversion behavior. However, it is encouraging that 12 percent of respondents indicated the information always influenced their route choices.

[1] The Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test is a paired difference test that compares two related samples, repeated measures, or matched pairs to determine whether the mean ranks differ.