There are two basic types of tools available for the prevention of noise incompatible land use: the physical techniques which reduce noise Impacts and the administrative methods available to local governments to encourage their use. Section 4 of the manual describes the range of design and construction techniques available. This section analyzes alternative administrative actions to ensure their adoption.

The available administrative techniques are categorized in this manual in five general groups:

Usually, the best solution for the municipality will be a combination of several techniques chosen to cover the widest possible range of noise incompatibility situations. In evaluating alternative administrative techniques, these factors must be kept in mind–

Despite the above limitations, the variety of available techniques is great enough to ensure that most communities will be able to find a combination of techniques appropriate to control local problems while remaining consistent with both state law and the administrative structure of the municipality.

One administrative technique not discussed in detail in this manual is the municipal noise ordinance. While a well written and properly enforced noise ordinance can be a major factor in the reduction of noise at its source, it can have little or no effect on controlling the compatibility of land uses constructed in areas where noise exists. Despite this limitation, a noise ordinance should be considered as an important component of a municipality’s legal and administrative structure.

Zoning is a commonly used local administrative technique to direct land use in accordance with a plan for orderly community growth. The zoning ordinance, or bylaw, specifies what type of land use is permitted in each zoning district. Zoning specifications have been used to control environmental emission, signs, off-street parking facilities, lot size, frontage, maximum building height, and ratio of open space to developed land. These precedents make zoning a useful tool for noise control in most localities.

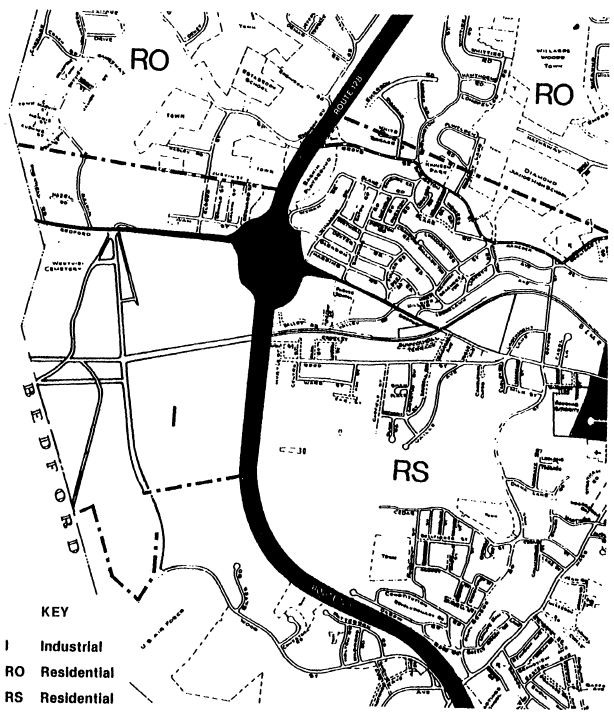

Since the areas within a community which are impacted by excessive noise probably do not coincide with the traditional zoning districts, a method must be developed to define the areas where any acoustical regulations apply. One method would be the creation of a series of new noise impacted zones on the existing zoning map. For example, each residential zone could be split into two zones identically controlled except for noise regulations. The same would hold true for each commercial, business or industrial zone (See Figs. 3.1 and 3.2).

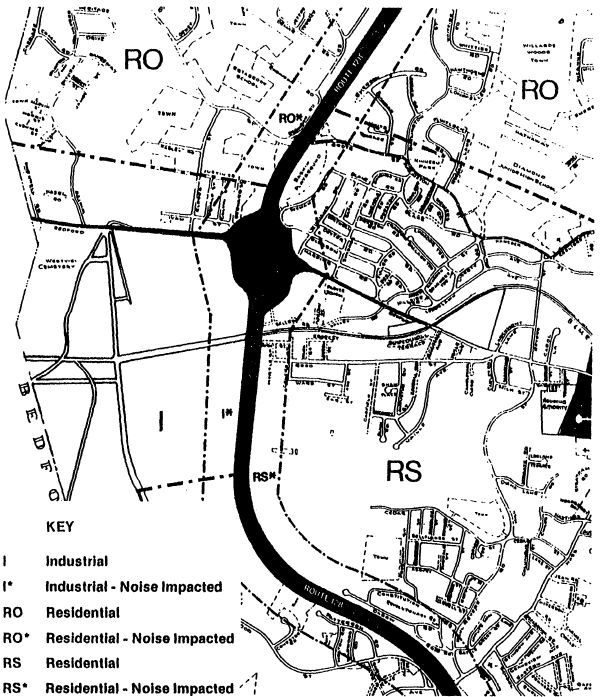

A simpler alternative to the creation of an entire series of new zones is the creation of a single “overlay zone.” An overlay zone is a special purpose zone which is superimposed over the regular zoning map (See Fig. 3.3). Often such zones are called “superimposed districts,” and they are used for a variety of reasons including wetlands protection and airport compatibility.

In this case, the overlay zone could be all land which is exposed to noise over a certain level such as 65 dBA. Or it could be defined, more easily but less appropriately, as all land within a certain distance from the highway, such as 500 feet. Land which falls in such a zone would be subject not only to the regulations pertaining to the regular zone in which it lies, but also to the additional regulations pertaining to the overlay zone. Such a technique is much less cumbersome legally and administratively than the creation of an entire series of special zones (single family residential, multi-family residential, commercial, etc.) in the noise impacted portion of the community.

Enforcement of the provisions of a zoning law has traditionally been accomplished prior to development and construction through the approval of plans and permits. While this before-the-fact enforcement process has several obvious advantages, it does not always provide complete protection against conditions which only become apparent after construction is well underway. This is especially true for items such as noise levels and noise attenuation measures which can only be accurately measured after the construction is complete.

In recent years, an increasing number of municipalities have instituted an additional enforcement measure the occupancy permit which provides effective after-the-fact enforcement.

Zoning can be used in four ways to ensure that future development will be compatible with nearby noise sources:

The land in a noise impacted area can be zoned for noise compatible uses, such as commercial, agricultural or industrial. It is a simple and direct technique which will work if the community has a noncumulative1 type of zoning law which prohibits, for example, residences or other sensitive uses in the industrial zone.

Unfortunately, there is usually not enough demand for such noise compatible land uses to afford every community the luxury of lining both sides of all highways with them. If all the communities within a region were to adopt this technique, they would make the land involved useless. Thus, there could be legal action against the community to recover damages for what could be considered a “taking without compensation.”

Furthermore, this type of strip zoning may not be compatible with other plans for the orderly growth and development of the community, or it could be in direct conflict with the development patterns of adjacent communities.

The technique of zoning noise impacted areas for compatible land uses should only be considered if:

Zoning can require specific construction practices or site design details which tend to ameliorate potential noise incompatibilities. These include:

There is a need for caution in the application of any of these requirements. While each of the techniques will usually reduce the effects of noise, there are peculiar factors about many sites which may render a given technique completely ineffective. It is also possible that other site-specific conditions have already reduced the noise impact thereby making the required techniques redundant. Either way, any extra money spent to satisfy the zoning requirement would not produce the desired beneficial effects. Thus, each requirement in a zoning ordinance for acoustical construction or site design practices should have a provision for exception if site-specific conditions so dictate. Local municipal structure will determine the exact form that the exception mechanism should take.

Buffer Strips: An overlay zone incorporated into the zoning bylaws could require a buffer strip between all residential construction in that zone and the highway. This requirement can be directly stated in the zoning bylaw, or it can be included in local development standards or subdivision rules and regulations as being applicable in the overlay zone. Some provision for plantings or ground cover within the buffer can be incorporated.

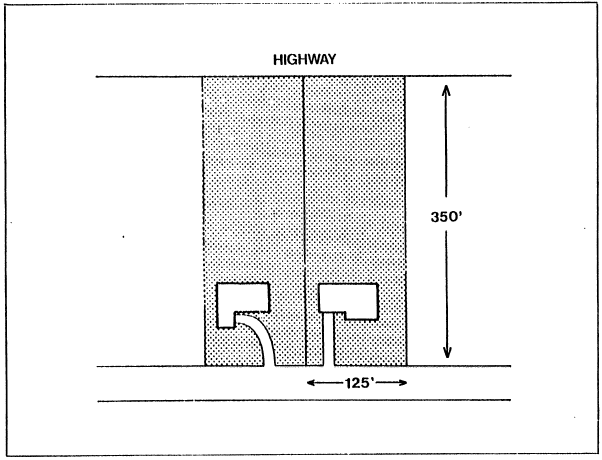

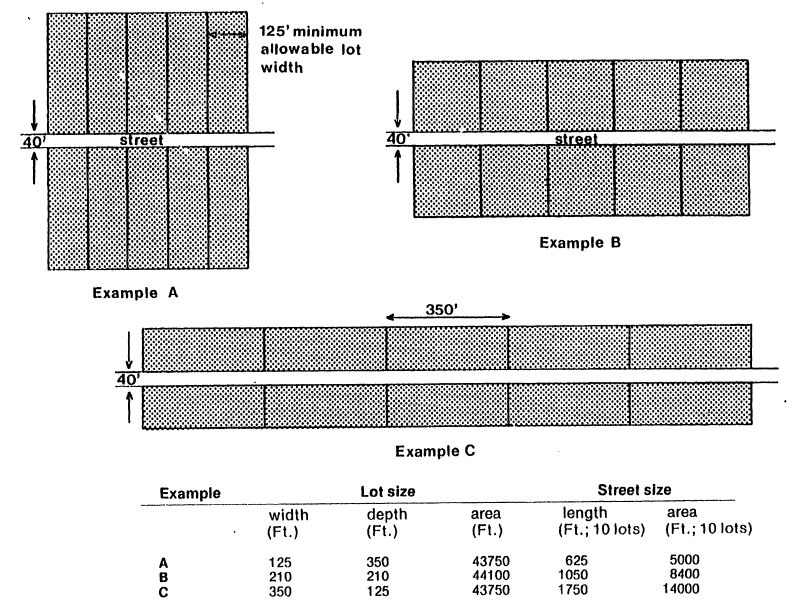

This technique will be most practical in areas where required lot size is relatively large so that the incorporation of the buffer strip as part of one’s backyard poses no unusual hardship. For example, in residential areas where minimum lot size is one acre (43,560 sq. ft.) and minimum lot width (frontage) is 125 feet, lots laid out with minimum frontage will be over 340 feet deep and could easily incorporate a buffer of 200 feet or more between the rear of the house and the rear lot line. (See Fig. 3.4) Lots of minimum frontage with house relatively close to the residential street are usually the most economical to create in a subdivision because of the high costs associated with street construction, driveways, and utilities. (See Fig. 3.5). Thus, no particular hardship is imposed on the developer. Conversely, areas zoned for 10,000 square foot lots could not incorporate buffer strips of any significant width without, in effect, decreasing the total number of buildable lots that could be created out of a subdivision tract. Whether the economic hardship thus created is justified must be determined on a local basis.

The following example of a model article incorporates the buffer requirement directly into the zoning bylaw.2

Screening and Buffers – Noise Impact Superimposed Districts

Screening and buffers shall be required in Noise Impact Superimposed Districts between permitted structures and the highway as follows: this strip shall be at least 100 feet in width; it shall contain a screen of plantings in the center of the strip. The screen shall be not less than 5 feet in width and 6 feet in height at the time of occupancy of such lot. Individual shrubs or trees shall be planted not more than three feet on center, and shall thereafter be maintained by the owner or occupants so as to maintain a dense screen year-round. At least 50 percent of the plantings shall consist of evergreens. A solid wall or fence, not to exceed 6 feet in height, complemented by suitable plantings, may be substituted for such landscape buffer strip by special permit. The strip may be part of the yard area.

No residential use, hospital, nursing home, church, school or day care center shall be constructed within the buffer strip. No such use, previously existing at the time of enactment of this section shall be extended into or within the buffer strip. No structure within the buffer strip shall be converted to any such use.

Construction of Noise Barriers: Construction of an earth berm or wall during development of a subdivision can be incorporated into the community’s zoning bylaw or into the development standards or the subdivision rules and regulations. Large individual nonresidential uses such as an office park can be protected from noise by berms or barriers if the proper stipulations are incorporated into the requirements for the appropriate development or building permits.

Barriers are not the ideal noise compatibility control in many geographical locations. There may be disadvantages of aesthetics, quality of life, and safety inherent in any barrier project which must be individually evaluated. Required construction of barriers can be limited to situations where other alternatives do not exist.

The following provisions, taken from the Development Standards of the City of Cerritos, California, could be adapted to local conditions elsewhere as permitted under state enabling legislation.

General Provisions

All proposed fencing, other than the fencing of an individual residential lot from another residential lot, shall be subject to review and approval of location, height, materials and color as follows–

| Example | Lot size | Street size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| width (Ft.) | depth (Ft.) | area (Ft.) | length (Ft.; 10 lots) | area (Ft.; 10 lots) | |

| A | 125 | 350 | 43750 | 625 | 5000 |

| B | 210 | 210 | 44100 | 1050 | 8400 |

| C | 350 | 125 | 43750 | 1750 | 14000 |

Height Restrictions: Height restrictions to limit residential buildings to a single story or to a maximum height can be directly incorporated into the zoning regulations which apply to a noise impacted area. height restrictions, when used in conjunction with natural or man-made barriers, can prevent some of the most severe highway noise directly hitting bedroom windows without banning all residential uses. Although very simple, this solution has some drawbacks:

One approach to height restrictions which overcomes some of the above drawbacks is to allow exception to the restriction if satisfactory evidence of alternative noise compatibility measures is presented.

Specific Construction Restrictions: Specific requirements for acoustical construction methods in the Noise Impacted Zone can be delineated directly in the zoning bylaws in most states. An alternative, which may fit more appropriately into the administrative structure of many communities is to put the requirements into the Building Code and to use the Zoning Bylaw merely to define the geographical area where the requirements are applicable.

Certain noise amelioration measures on large scale developments are dependent on the amount of flexibility that the developer has. Cluster development and planned unit development (PUD offer a developer incentives to set aside major portions of a tract for buffer strips and to locate buildings in natural low-noise pockets on the tract. A well written and properly administered cluster or PUD provision in a zoning ordinance can grant this flexibility and still protect against unwanted advantage being taken of the cluster/PUD concept.

Cluster residential development is a zoning technique under which the residences on a large development tract are placed in small groups, or “clusters,” while a major portion of the tract remains as open space. Usually this is accomplished by allowing a smaller individual lot size than zoning normally allows, but with a provision that the total number of units constructed will not be increased.

Planned Unit Development is similar to cluster development, except that the development is not completely restricted to residential uses. Under this technique, a large tract is developed as a somewhat self-contained community with residential uses plus some shops or other commercial uses primarily intended for use by the residents of the tract. Often, some community facilities are also included in the PUD. PUD zoning contains provisions for reduction of lot size and creation of open space similar to those found in cluster zoning.

PUD and cluster are forms of “incentive zoning” in which the developer is given some special incentive in return for providing a development more desirable to the municipality. In cluster zoning, the developer gains by having to construct fewer and shorter streets and by often being able to create more marketable lots; while the municipality benefits from decreased public costs, such as road maintenance, shorter school bus routes, and fewer miles of police patrol routes. The municipality also receives the benefit of having permanent open space created at no cost. Under PUD, the developer also gains by being permitted to build valuable commercial uses in an otherwise residential zone, but in return he may be called upon to provide some community facilities such as recreational facilities or even land for schools as a part of the development.

Whether a cluster development or a PUD is a permitted land use is dependent on the state enabling acts. For example, communities in Massachusetts can adopt zoning which permits cluster development, although they cannot require it. At present, however, permitting a PUD is of questionable legality under the Massachusetts zoning enabling act.

Actually requiring that a tract be developed as a cluster or as a PUD is presently illegal in many states. The decision must be left to the developers, but properly structured incentives can motivate them strongly to choose the cluster or PUD option.

Cluster and PUD options will only work in areas where zoning density is low enough to allow the clustering of residences on smaller than usual individual lots without creating crowding. In areas of densities higher than two or three single family residences per acre, this type of development is not practical without use of multi-family buildings. Where space allows, cluster and PUD zoning can provide excellent noise compatibility control in addition to often providing for a quality of development unobtainable in more conventional subdivisions.

The concept of cluster and PUD development is too complex to be completely discussed in this manual, and should certainly not be adopted merely as a tool to obtain noise compatibility. If, however, a municipality has, or plans to adopt, a cluster or PUD provision, inclusion of noise compatibility into its regulatory structure would be appropriate.

Zoning can be used to define conveniently the geographical areas where local revision procedure or certain local regulations apply. The details of the applicable procedure or regulation need not appear as part of the zoning regulations. Four of these are possible methods to obtain noise-compatible land use development control:

Special Permits: A zoning or other local law could require special permits prior to the construction of typically noise-incompatible land uses in a noise impacted area. Thus, such land uses would be permitted only if, in the judgement of the appropriate local official or board, they are deemed to satisfy certain preconditions. Exactly what permit conditions are possible under state enabling legislation varies considerably from state to state.

Environmental Impact Statements: Whenever the state laws permit, the local requirement of an environmental impact report for any construction in a noise impact district could be a most useful tool to educate and motivate the developer. And, as state laws change, the impact report could become the basis of actual noise compatibility enforcement.

Building Code: In municipalities where the building code is already administered by a well-established municipal organization, additional specifications in the building code can be a convenient and inexpensive way to require acoustical construction practices such as sound insulation or sealed windows. An overlay zone on the zoning map can often be the most practical way of defining the geographical area where these additional specifications apply. Building code acoustical requirements are treated in detail in a subsequent section of this manual.

Acoustical Analysis by an Architectural Review Board: The zoning regulations can also be worded to require acoustical analysis of all proposed development within areas of potential noise impact. Such areas could be defined by an overlay zone. The actual analysis might be done by a member of the municipal staff or by an architectural review board. The role of architectural review boards is discussed in a subsequent section of this manual.

Zoning is not the only legal tool available to local governments to control noise incompatible land use. Subdivision control laws, building codes, health codes, occupancy permits, special permit procedures and environmental impact statement requirements can all be used to prevent incompatible land uses from coming into existence.

Although in many states subdivision control laws and zoning are closely related, they are usually separate laws sometimes administered by different local authorities. In Massachusetts, for example, the building inspector of a town is the zoning officer who must enforce the town’s zoning bylaw. The Planning Board, on the other hand, administers subdivision control through the rules and regulations which it has adopted.

Subdivision control law is administered on the local level by a planning board or planning officer using subdivision rules and regulations, development standards or similar documents. These rules and regulations contain the various requirements which must be met by a developer in the creation of a subdivision. Such things as storm drainage, pavement type, curbs, sidewalks, maximum grades in streets, street width, underground utilities, and recreational land can all be specified in these requirements.

The requirements which a planning board can build into its rules and regulations are very specifically delineated in the state laws on subdivision control. Whether a noise compatibility element can be required as part of a subdivision submittal or whether requirements can be made for acoustical site planning or architectural review is dependent on the state laws. It may be possible, for example, to require a buffer strip or to require acoustical site planning in the area near a highway. It may also be possible to specify acoustical limits in decibels which cannot be exceeded without acoustical construction techniques.

In addition to direct specification of acoustical criteria for developments, the subdivision control rules and regulations can be used as a bargaining tool to obtain acoustical considerations from developers. In many states, the rules and regulations adopted under subdivision control law may be waived for sufficient reason by the planning board or planning office. Thus, there is an implicit ability to bargain for acoustical improvements.

Local building codes can be a powerful tool to ensure that any of a series of noise compatibility measures are taken. Requirements can take four basic forms:

As with most legal techniques, the choices range from laws which are very specific but not always appropriate in a given case to laws which are vague but which can be interpreted to optimize each individual situation. The key in writing a viable noise compatibility section for a building code is to make it strong enough to be enforceable and yet discretionary enough to be flexible. One way to attempt to satisfy both of these goals is to define the specific requirements as being applicable only in areas where the expected or actual exterior noise levels exceed certain levels.

Building codes have two weaknesses when used alone as a noise compatibility control:

Specific Construction Techniques: The hypothetical section of a building code which follows attempts to combine strength with appropriate applicability by granting the local building inspector the ability to waive any provisions when the specific conditions so warrant. Thus, the required construction requirements could be reduced, for example, to involve only those walls of a building directly facing a noise source. Or, some provisions could be waived entirely if the conditions involved in the individual case make them unnecessary.

The particular wording presumes that the local building inspector has some way of defining areas of the community where a noise compatibility problem may occur. Alternative wordings could be chosen to define the applicable areas by measurement with a sound level meter, by a noise contour map, by an overlay zone on the zoning map, or by including all areas within a specified number of feet (such as 500) of certain highways. Also, an alternative wording could make some person other than the building inspector responsible for interpretation of applicability of the code provisions.

Acoustical Construction Requirements

In all areas determined by the building inspector to have the potential of significant noise impact, the following design requirements shall apply–

Provisions of this section may be waived or otherwise reduced when, in the opinion of the building inspector, the walls as designed will have a Sound Transmission Class of 50 dB, or when, in the opinion of the building inspector, the interior noise levels after occupancy will not exceed 45 dBA more than six minutes out of each hour. If these requirements are so waived or otherwise reduced, the building inspector shall require satisfactory proof of achievement of expected noise reductions prior to issuance of an occupancy permit.

Specification of Exterior and Interior Noise Levels After Construction: Instead of requiring in a building code that certain acoustical construction materials be used, a performance standard could be set requiring the attainment of specific interior noise levels. An example of exterior and interior performance standards which might be applied are those adopted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for use by builders of federally funded housing. (See Fig. 3.6)

| Exterior | discretionary – normal acceptable | 65 dBA – L33 (not to be exceeded more than 8 out of 24 hours) |

|---|---|---|

| clearly acceptable | 45 dBA – L2 (not to be exceeded more than 30 min. out of 24 hours) |

|

| Interior | clearly acceptable | 45 dBA – L33 (not to be exceeded more than 8 out of 24 hours) |

| 55 dBA – L4 (not to be exceeded more than 1 out of 24 hours) |

||

| 45 dBA – L6 (night) (not to be exceeded more than 30 min. out of 24 hours) |

Noise Attenuation Requirements: Requirements for noise reduction can be definitive, requiring, for example, a sound transmission class of 55 dB. Definitive regulations are clear and easy to enforce, but unfortunately they are not always appropriate for each individual case due to the differences in ambient noise levels.

Interpretive Regulations: The prime disadvantage to any regulation which requires acoustical construction techniques is that such techniques are not always the optimum solution to noise incompatibility problems because they are so expensive. Certainly, site planning, plantings and acoustical design are much more desirable solutions to a noise problem. For this reason, it is important that the regulation contain a mechanism for exception if other methods will achieve the desired low noise levels.

Precise noise standards can be left to the interpretation of a local official by requiring, for example, that the Building Inspector specify an adequate STC in each particular case. Interpretive regulations can take advantage of human judgment to provide the optimum solution for each case, but they are subject to the human frailties of possible arbitrary, emotional, or even dishonest decisions. Interpretive decisions may be more likely to result in court actions than definitive regulations, particularly if the interpretation is thought to be arbitrary or otherwise inconsistent with local precedents. In the following sample section of a building code4, a compromise between definitive and interpretive regulations is achieved by including a provision for waiver at the discretion of the building inspector.5 Whether this is the solution for a given community can only be determined by a careful review of local conditions.

Acoustical Construction Characteristics – Noise Impact Superimposed Districts

No residential use, hospital, nursing home, church, school, or day care center shall be constructed within the Noise Impact Superimposed District unless evidence is given that a Sound Transmission Class of at least 55 dB will exist in all exterior walls which face toward the highway, are perpendicular to the highway or are placed at any angle between facing the highway and perpendicular to the highway. No such use shall be constructed unless evidence is given that all other exterior walls will have an STC of not less than 50 dB.

Within 200 feet of the highway in the Noise Impact Superimposed District, no such use shall be constructed unless all rooms of the building are served by an air-conditioning system adequate in the opinion of the Building Inspector (or other appropriate official) to maintain a constant temperature of 68 degrees.

The provisions of this section may be waived or otherwise reduced if, in the opinion of the Building Inspector, the particular location and surroundings of the proposed building are unique to the area and will provide for peak noise levels less than 45 A-weighted decibels (45 dBA) within the living and sleeping areas of the building.

Local and county health codes exist almost universally throughout the United States. Many of them could be adapted easily to include a provision for noise compatibility in new construction. In some respects, the health code has distinct advantages over the other legal and administrative techniques listed in this manual:

An example of the simplicity of using the health code as a noise compatibility control can be seen in the case of Orange County, California. The County’s zoning, subdivision, building and health codes apply to all of the unincorporated areas of the county.

The County Health Department requires that the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) requirements for acceptable interior and exterior noise levels, as outlined in HUD Departmental Circular 1390.2, be met.

The submittal of any development plan requires, under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), that an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) be submitted. A mandatory element of the EIR is a description of actual and predicted noise levels at the site and a description of methods proposed to mitigate any excessive noise impacts.

The County evaluates the submittal so as to confirm the expected noise levels both inside and outside the proposed buildings. If it is clear that the HUD standards will be met, the plan receives approval with respect to noise compatibility. If there is some doubt whether the HUD standards will be met, the approval is made conditional on an occupancy permit which will not be issued unless actual measurements, taken after construction is complete, confirm that the standards have been met. Development plans which appear incapable of meeting the HUD standards are disapproved unless revision is made.

The Orange County system is slightly more complicated than merely requiring achievement of certain standards before issuance of an occupancy permit in that the county does evaluate the potential noise levels at the time of submittal.7 such an evaluation is helpful because it gives the developers knowledge of what to expect early in the development process before excessive money has been spent on construction. This in turn reduces the chances of successful court action against the county, should an occupancy permit actually be refused.

Compliance with all of the administrative techniques previously discussed – zoning, subdivision laws, building codes and health codes – can be made mandatory by conditioning the issuance of an occupancy permit on it. An occupancy permit, or certificate of occupancy, is a document issued by some local authority such as the Building inspector or the Board of Health. It certifies that a building meets certain minimum standards and is therefore fit to be occupied.

An occupancy permit, as opposed to a building permit, comes after construction or modification of a building has been completed. If the building is judged by the appropriate local official or officials to be adequate for the intended use, then the occupancy permit is issued. Without such a permit, the building cannot be occupied.

Some of the approvals that might be needed prior to issuance of an occupancy permit include approval from the plumbing, electrical, and building inspectors of the construction and workmanship; approval of the fire department regarding fire safety; and approval by the health department concerning various provisions of the sanitary code.

If an occupancy permit procedure exists within the local government, incorporation of noise standards into it is usually an easy task. If such a procedure is legal under state law but doesn’t exist in the local government it should be considered not merely as a noise compatibility tool, but also as a method of easy enforcement of other local building standards.

The occupancy permit’s strengths lie in the fact that it is based on simple direct measurement and it is the final step in the land development process. Its principal weakness comes from the potential financial hardships which it may impose by denying use of a building after considerable construction expenditures.

Although the occupancy permit procedure can successfully stand by itself as a noise compatibility control procedure, its use in conjunction with other control techniques which identify potential problems at an earlier time is less likely to cause financial hardship for the builder and possible lawsuits for the local government.

A sample section of a zoning bylaw which requires a certificate of occupancy follows. This particular sample makes the Building Inspector the enforcing authority. It could be rewritten to specify the Board of Health, the planning office, or some other appropriate municipal authority.

Certificate of Occupancy Required

It shall be unlawful to occupy any structure or lot for which a building permit is required herein without the owner applying for and receiving from the Building Inspector a certificate of occupancy specifying thereon the use to which the structure or lot may be put. Failure of the Building Inspector to act within ten days of his receipt of the notice of completion of the building and the application for an occupancy permit shall be considered approval.

The certificate of occupancy shall state that the building and use comply with the provisions of the Zoning Bylaw and of the Building Code of the Town of_____________ in effect at the time of issuance. No such certificate shall be issued unless the building and its use and its accessory uses and the uses of all premises are in conformity with the provisions of this Bylaw and of the Building Code at the time of issuance. A certificate of occupancy shall be conditional on the provision of adequate parking space and other facilities as required by this Bylaw and shall lapse if such areas and facilities are used for other purposes.

A certificate of occupancy shall be required for any of the following in conformity with the Building Code and this Bylaw:

Certificates of occupancy shall be applied for coincidentally with the application for a building permit, and shall be issued within ten days after the lawful erection or alterations of the building is complete. Such certificates of occupancy shall be posted by the owner of the property in a conspicuous place for a period of not less than ten days after issuance.

Where zoning ordinances exist, some land uses are often allowed only under special permit. Some municipalities which do not have zoning have a special permit procedure as part of their general municipal ordinances. The specific land uses are permitted only if, in the judgment of the appropriate local official or board, they are deemed to satisfy certain preconditions. A zoning or other local law could require special permits prior to the construction in a noise impacted area. Exactly what permit conditions are possible under state enabling legislation varies considerably from state to state.

The principal advantage of the special permit procedure over other more specific types of restrictions is that each situation is treated individually. This is often desirable if a sound and rational solution is to be reached since the many variables involved, including terrain, traffic, and noise sensitivity, do not lend themselves to generalized solutions. What is needed is a site by site analysis and application. No law, no matter how carefully written, can cover all of the factors concerning a given situation in as complete a manner as can a sound administrative judgement.

Another advantage is that the local rules governing a special permit procedure can be structured to require the appropriate acoustical analysis as part of the permit application. Thus, the potential developer, rather than the local government would bear much of the expense involved.

The very advantage of the special permit procedure the inclusion of human judgement is also the major disadvantage. While the judgement of capable, knowledgeable and dedicated people is far better than mere application of inflexible standards, a poorly administered judgement process is subject to emotional, arbitrary, or even dishonest decisions.

This does not mean that the special permit procedure should be discarded as too much of a risk. The potential benefits to be gained are too significant. Rather, certain questions must be satisfactorily answered in considering the special permit procedures:

Properly structured and administered, the special permit procedure is a powerful and just method of achieving noise compatibility.

In the following sample8 of a special permit section for a zoning bylaw, provision is made for use of art occupancy permit as a further tool of the special permit procedure. Where legal, this minimizes the possibility of the local permit issuing authority being misled by false technical data during the special permit procedure. Obviously, this requires that occupancy permits and their issuance be defined elsewhere in the bylaw.

Also, the sample section presumes that some “Board”9 exists or can be created and that the Board has some standards or “rules and regulations” regarding the content of special permit application submittals. If this is not the case, such standards may be incorporated into the zoning bylaw.

If a local community desires a provision for exception to these noise criteria, at the judgement of the Board, this can be achieved by a slight rewording of the sample section.

Special Permit Procedure for Noise Impact Superimposed District

No residential use, hospital, nursing home, church, school or day care center shall be constructed within the Noise Impact Superimposed District except by special permit of the Board. No such use previously existing at the time of the adoption of this bylaw may be expanded into or within the Noise Impact Superimposed District except by special permit of the Board. No existing structure within the Noise Impact Superimposed District shall be converted to such use except by special permit of the Board.

Applications for such special permits shall contain all information required in the rules and regulations of the Board plus the following:

Prior to issuance of special permits required by this section, the Board shall determine that the noise levels will be successfully reduced to the following standards.10

The Board may include as a condition of the special permit, a requirement for actual measurement after completion of construction to confirm that the standards set forth in this section have been achieved before an occupancy permit shall be issued.

There is a rapid trend toward requiring that developers identify and analyze all impacts that a proposed development will have on the environment. Air and water pollution, noise, impacts on open space, and impacts on wildlife are a few of the factors for which analysis may be required. The results of the analysis, when submitted to permit granting public authorities, becomes a useful tool to identify problems and to decide which situations must be rectified before a permit is granted.

State laws vary considerably in the requirements for submittal of environmental impact statements and plans to mitigate adverse impacts. California, for example, requires an extensive environmental impact report (EIR) on most private and public construction projects large enough to require a building permit. These reports are required to contain a detailed noise element. Several other states have adopted legislation requiring environmental impact statements, or an equivalent procedure. However, most of these treat noise in a general fashion, if at all. Also, these procedures are not applicable to all projects on the local level. For example, a ruling in Massachusetts has limited the local scope of environmental impact proceedings to projects involving redevelopment and housing authorities.

No law, regulation, or financial incentive controlling the use of land owned by others can ever be as absolute as actual ownership by the municipality of the land or of restricted easements on the land. This section describes alternative types of municipal ownership and methods of acquiring land or easements.

While municipal purchases of massive amounts of land might create unacceptable financial burdens in direct outlays and lost tax revenues, the actual circumstances of municipal ownership are often quite the opposite. There are several ways that a municipality can acquire clear title to land at a minimal cost. Easements, an effective form of partial ownership of the land can also often be obtained for less money than outright purchase. Finally, the loss in tax revenue due to the removal of municipally acquired land from the assessed tax base may be much less expensive than the demand for new municipal tax revenue that would have been necessary to fund the municipal services that would have been required if the land were developed.

The pages that follow elaborate on some of the factors involved in municipal ownership of noise-impacted land. The options to the community are to leave the land undeveloped, to develop it with compatible uses, or to sell it with appropriate covenants on the deed to ensure that only compatible uses are developed.

There are two factors which a municipality must consider in deciding the appropriateness of land acquisition as a policy to promote noise compatible land use:

1) Acquisition Costs

The primary acquisition cost to the municipality is the purchase price of the land. If this purchase is financed by municipal bonds, the interest on these bonds must also be included in the purchase price. Additional hidden costs to the municipality include:

The primary determinant of the land acquisition cost to the community is the mode of acquisition used by the municipality. Five alternative methods can be considered: 1) Outright purchase 2) Eminent domain taking 3) Gift 4) Public land acquisition under subdivision development 5) Transfer from other governmental agencies.

Each of these methods, appropriate under certain circumstances, will be discussed in the paragraphs that follow.

Purchase: The purchase of property by a municipality is an effective, but expensive way to achieve noise compatible development. Usually the fact that the municipality has a plan to purchase land adjacent to highways will drive up the price of land on the open market.

Eminent Domain Taking: Eminent domain proceedings are limited by state law. The purpose of the takings, and the intended use of the land, are the major factors in determining whether the eminent domain is legal. The major criterion is the extent to which there is a public purpose served by the taking, a condition which must be satisfied if eminent domain is to be valid.

The public purposes served by eminent domain takings for noise compatibility are subject to question in the courts. However, strong arguments can be made that public health is preserved by prevention of human exposure to excessive noise levels, and that the quality and value of the community as a whole is improved by not having residences or other incompatible land uses in a noise impacted area.

The eminent domain process runs the risk of being subject to local opposition because of the involuntary nature of the land acquisition. Furthermore, the cost of the taking is set by the court and may be considerably higher than the community originally anticipated. Both of these factors must be evaluated carefully prior to implementation of an eminent domain proceeding.

Gifts: Gifts, particularly restricted gifts, represent a frequently overlooked source of municipal land. There are often significant tax advantages (both property tax and personal income tax) to the individual who gives land to the community. Furthermore, restrictive covenants (such as forever maintaining land as open space) can make the donation of such land more attractive.

Acquisition under Subdivision Development: Another method of acquisition of land at little or no cost to the community is that of receiving land as part of the subdivision process. This is most practical in cluster subdivision and planned unit development situations because both of these situations usually require the creation of public open space as the condition of reduced lot sizes. A properly worded zoning law, combined with appropriate administrative procedures, can ensure that a portion of such land be a buffer between a highway and adjacent land uses. The municipal uses of land received in this manner would be restricted primarily to open space, conservation, and recreational uses, helping to solve the noise compatibility problem. This type of land acquisition is quite dependent on the bargaining ability of the local officials at the time that they are considering the plans for approval.

Transfer from Other Governmental Agencies: Some of the land acquired during the development of new highways may be of little or no use to the highway department. For example, highway regulations may permit the purchase of an entire parcel of land even if only a small portion of it is required for the actual right of way. The transfer of this land to the municipality can both relieve the highway department of the responsibility of its maintenance and also serve the municipal goals of noise compatibility control.

2) Social Costs and Benefits of Continued Public Land Ownership

Local municipalities must consider not only the initial costs incurred in acquiring land, but the costs and benefits associated with the continued public ownership of that land. Five components of municipal ownership are:

Municipalities can use land acquired in noise impacted areas in three ways: passive municipal uses, active municipal uses, and non-municipal uses.

Passive municipal uses include:

Active municipal uses include:

Non-municipal uses include:

Restrictive easements are often obtained by municipalities to protect scenic views, watersheds, well sites, and conservation land. After having granted a restrictive easement, the land owner can use the land only in ways not prohibited by the terms of the easement. For example, an easement can be written to restrict the owner from building on the land covered by an easement.

Easements for noise compatibility purposes could restrict buildings in the portions of the land nearest the highway or other noise sources. They could prohibit the cutting down of trees which presently form a natural buffer, or the destruction of an existing hill which presently acts as a barrier. Or, the easement could merely restrict certain types of buildings such as residences unless specified acoustical construction techniques are used.

An important advantage of municipal possession of an easement is that it can often achieve effective control over land at a much lower cost than actual municipal ownership. Easements can be obtained by five of the methods as previously listed for obtaining ownership: purchase, eminent domain, gifts, subdivision conditions, and transfer of other governmental agencies. The difference, however, is that title to and limited use of the land remains with the original owner, thus making the cost of obtaining easements much less than the cost of outright ownership.

For the land owner, the giving of an easement can often result in a significant reduction in his property and income taxes. A property tax reduction can be arranged as a condition of the easement to reflect the lessened value of the land because of the existence of the easement. It may be necessary to write some guarantee of this lower property tax assessment into the easement agreement in order to convince the property owner of the benefits of granting the easement to the municipality. Significant income tax reductions may also occur because the owner may deduct the entire value of the easement as a “charitable contribution.”

The cost of an easement to the municipality varies with the terms of the easement. First, the price is a function of the value of the rights which the owner is giving up. If the easement causes little or no change to the land use options available to the landowner, then the cost of the easement should be small or perhaps free. If, however, the easement greatly restricts uses which could otherwise have been possible, then the easement cost will approach that of actual purchase. Careful attention should be given to ensure that no unnecessarily restrictive (and therefore costly) conditions are written into easements.

Conservation Trusts: A variation of an easement is a conservation trust. The owner of a parcel of land gives land to the community to be held in a conservation trust fora specified length of time. Since the gift is for a specified period of time, the original owner retains residual rights to the land as a long-term investment. If a local conservation commission or similar agency exists, it can, depending on its legal status, become the holder of this land.

While the land remains in the conservation trust, no taxes are paid on it by the land owner. The land owner retains residual rights for future possible use of the land, and is guaranteed the fact that the land will not be developed. This can be particularly advantageous to the land owner who is feeling pressures (due to increasing taxes or increasing land value) to sell land which is valued for scenic or other qualities.

To the community, this represents an inexpensive way of controlling land to regulate orderly community growth as well as potential noise incompatibility. However, safeguards should be built into a conservation trust program to ensure that the trust benefits the municipality in general and is not merely a way in which one land owner gets protection for his or her forest preserve at the expense of the taxpayers.

The cost of significant municipal services which can be saved by preventing development of the parcel is a benefit to the municipality only if the parcel would, in fact, be developed if the trust did not exist. The prevention of future noise incompatibility problems or the gaining of public access to desirable woodlands also may benefit the municipality. In general, land held in conservation trust should fit into a municipal or regional open space plan, and not be randomly chosen on the sole basis of availability.

In addition to direct legal controls on potential developers, financial incentives in the forms of tax reductions and reduced costs exist. This section examines some of these techniques.

One often overlooked, but very effective tool to shape land use development is the municipal property tax. Tax incentives can be used to discourage development of incompatible land uses, to encourage the creation of buffer strips, and to encourage the use of acoustical construction techniques. All too often however, the effect of a municipal tax policy is to encourage rather than discourage such development.

Municipal tax incentives can take several forms:

The most effective of these tax incentives is the first: assessment to discourage the development of land. Yet, all too often, local assessment policy has just the opposite effect in that it encourages and sometimes forces the development of land.

A widespread policy among local assessing bodies is to tax all property at its potential “highest and best use,” thereby creating the broadest possible tax base. The logic behind this type of policy is that a given amount of municipal revenue can thus be raised with the smallest possible tax per dollar of assessed valuation. In theory, this will keep everyone’s tax bill to a minimum. If the municipality’s interests are best served by the land’s not being developed, the object would be to assess the undeveloped land as low as possible rather than assessing it according to its “highest and best use.” Conversely, high taxes on undeveloped land may give the owner no financial alternative other than selling to a developer.

However, such an assessment policy will not be without potential problems and these problems should be addressed and overcome. The potential problems fall into three general areas:

Each of these will be treated in turn.

The legality of incentive assessment policies varies from state to state. If state law requires “full and fair evaluation” without specific exemption of undeveloped land, this assessment policy may not be legal. Even in states which permit specific exemptions (such as Massachusetts, which allows agricultural land to be assessed as such) there is question whether the scope of these exemptions can be expanded (such as to include wooded areas, open spaces, or underdeveloped land). The legal constraints must be evaluated for each given state.

A second issue which reflects on the legality of incentive assessment policies is the equity with which the policy is applied. If, for example, it is desired to apply such an assessment policy to all agricultural land near a major highway, then it will probably be necessary to apply the same policy to all agricultural land throughout the municipality. Whether such universal applicability of low value assessments is compatible with other municipal goals is a question to be answered on a local basis.

Perhaps the most frequent problem associated with an incentive assessment policy is that of obtaining public acceptance of it. It is obvious that any action which lowered the assessment value of property would narrow the tax base of the municipality and thus raise the tax rates and the tax bills of those whose property was not reassessed. (This assumes that the total amount of money to be raised through the property tax does not decrease.) And an increase in tax bills is by no means a guaranteed method to inspire enthusiastic public acceptance.

Often, however, these assessment policies will actually prevent much of the future increase in taxes that would otherwise have been necessary. This is true whenever the increased costs of providing municipal services to new developments are greater than the additional tax revenues that the new developments will generate.

The chance of obtaining public acceptance can be increased if it can be demonstrated to the public that a greatly increased tax rate (due to increased demand for public services) is the alternative to a lesser increase due to narrowing of the tax base. Also, the desirability of maintaining the land in its present state for other than financial reasons can also be used as an argument.

A major financial incentive to encourage builders and developers to utilize noise compatible construction and development techniques is to relax enforcement of certain provisions of some local regulations. Often, local regulations or codes such as development standards, and subdivision regulations allow local officials some discretion in their enforcement. This discretion can become an important bargaining tool to bring about various noise compatible development or construction techniques. Thus, the builders or developers can financially benefit from relaxation of local regulations or codes, if in turn they agree to provide for appropriate acoustical development or construction.

For example, a local regulation might ordinarily require sidewalks on both sides of all streets within a new subdivision. Perhaps this requirement could be waived on one side of some of the shorter streets without any adverse effect on the quality of the subdivision. The resulting savings could be enough to compensate the developer for the cost of acoustical site layout or construction of a barrier or berm. Likewise, a waiver which allows substitution of molded asphalt or bituminous concrete curb for ordinarily required granite curb can save the developer several dollars per foot of road. The developer might find such a saving to be well worth the added cost of providing a subdivision that is acoustically compatible with neighboring noise sources.

The specific noise impact reduction techniques that can be obtained in this fashion include acoustical site planning, berm or barrier construction, buffer strips, acoustical architectural design, insulation, and other construction techniques.

Certain potential problems should be addressed and overcome if such a policy is to be attempted. These problems fall into five categories:

A municipality can provide a variety of services to ensure that new development is compatible with nearby noise sources. Some of these services are surprisingly effective. Municipal educational services cannot be as definite as legal regulations or as absolute as ownership of the land but they can, for a very low cost, supplement these other administrative methods.

Four municipal services will be discussed in the pages that follow:

One of the many benefits that a local community can derive from an architectural review board is noise compatible design control.

An architectural review board (ARB) is a local board—either official or unofficial—composed of citizens expert in architecture and related fields who analyze proposed development and construction and who provide the appropriate municipal officials with advice based on this analysis. Often the ARB is composed of members who have volunteered their part-time services to this community project.

Although it is often not an official branch of the municipal government, the ARB can derive significant strength from the support which it receives from the agencies and officials who receive its advice. Conversely, an ARB, no matter how skilled its members may be, is of no real value if its advice is not heeded or if its decisions are not supported by the local officials who have the legal authority to enforce such decisions. This support, or lack thereof, is perhaps the key determinant of whether or not the ARB will be a successful influence on the quality of community growth.

In the area of noise-compatibility control, the ARB can recommend any of a vast number of physical techniques such as site design, architectural building design, insulation, acoustical windows, subdivision layout, buffer strips, and berms and barriers. Again, it should be emphasized that noise compatibility control is only one of several benefits that will accrue because of an architectural review board. Other benefits such as continuity of architecture, community planning, and quality of design and construction can be equally important.

For a municipality which has the technical ability on its staff, an informal design review service can be the optimum way to ensure that future development and construction is compatible with existing nearby noise sources.

An effective design review service can consist of nothing more than an employee of the municipal engineering, planning, or building departments who specifies certain minimum requirements for insulation, window construction, wall construction, barriers, berms, or buffer strips on a copy of the plans as submitted by the developer. The employee can also be one who would normally review the plans during the permit or subdivision approval process, and the addition of the noise specifications would thus add only a few minutes to the review process. The developer would then have a clear indication of the noise compatibility measures which the municipality desired.

The specifications passed on to the developer could be requirements, the subject of negotiation, or mere suggestions, depending on the strength of local laws and the specific wording of state enabling legislation. Even specifications which are mere suggestions stand a good chance of being followed especially if they do not represent a major added cost to the developer or builder, or if they can be expected to improve the market value of the buildings.

It should be remembered that the developers or builders do not necessarily know the expected noise impact on a planned building, the amount of noise attenuation that is desirable, or the optimum way to achieve that attenuation. As such, the builder is likely to welcome the advice of a municipal employee who is reasonably cognizant of noise attenuation measures and expected local noise levels.

A passive form of municipal design service consists of merely maintaining a convenient library of acoustical design and construction techniques along with some background literature on expected noise levels. This is an appropriate venture in many smaller communities where the municipal planning and engineering offices may be part-time or combined with other municipal functions. It is very inexpensive. It requires a minimum of personal attention by municipal officials or employees. And, it provides the local designers, builders, or developers with otherwise unavailable information which they may be quite willing to use in their planning.

Even a library consisting of this manual, a map showing the areas of noise impact,11 one or two of the references listed in section 5.3 and a handful of advertising brochures from manufacturers of insulation or other acoustical building materials would provide an information source significantly greater than that readily available to the average builder. A single shelf in the town hall or the local library may be all that is needed.

While this may seem to be a naively simple solution to a complex problem, it should again be remembered that many designers and the vast majority of all builders and developers have had little or no experience with noise compatible construction and design. The library, perhaps set up and maintained by a citizen volunteer who has some knowledge in this topic, can provide the builder or developer with the appropriate information. Actual use of such a service can be urged by the local departments which issue permits or which approve subdivision plans.

Public awareness of the severity of noise impacts and the physical techniques that can lessen these impacts can be an important factor in determining the marketability of a building, especially a home. This can have a direct financial effect on the builder through both price and quickness of sale. Accordingly, public awareness can be a welcome tool in a municipality’s efforts to achieve noise compatibility control.

The format of a public information service will vary from community to community depending on local skills and facilities. A very simple yet effective technique would be to indicate areas of noise impact on all municipal maps. Since prospective home buyers often obtain such a map, they would thus be aware of the potentiality of the noise incompatibility. While certainly not all potential buyers will be aware of this information, the fact that some of them will may be enough to motivate the builder or developer.

More sophisticated public information services could use maps displayed prominently in the library or at the municipal offices. Publicity in the local press or cooperation from a local public service organization such as the Chamber of Commerce can be effective in some localities.

Like several of the other administrative techniques listed in this manual, a public information service will not by itself be the cure to all the community’s noise compatibility problems. It can, however, be a useful force when used in conjunction with other administrative techniques.

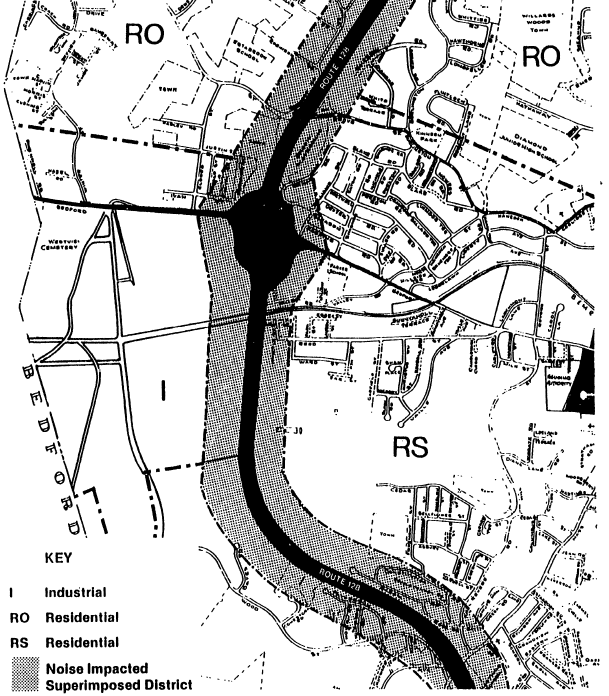

The various administrative techniques which may bring about noise compatible land use are listed in Figure 3.6. While some communities may consider a single technique—such as the health code—adequate to provide the desired control, most local governments will find that a combination of several techniques is best in terms of effectiveness, cost, and desirability of results.

One such combination might be zoning to require buffer strips, health code standards enforced by occupancy permit, and an architectural review board. Under such a combination, the near-absolute authority of the health code is complemented by two other methods (zoning and the ARE) that will tend to bring about the most desirable physical solutions. Also, the required buffer strips and the architectural review should significantly reduce the number of instances where enforcement of the health code requires expensive modifications to buildings after they have been constructed. This combination would work well in municipalities where low expected land use density made buffers practical, where an effective architectural review board could be established, where the health code could be made appropriately strong, and where existing development in and near the noise impacted area was slight.

A combination more appropriate in a municipality where high land values dictate relatively dense land use development might be industrial zoning of major tracts with building code requirements for acoustical insulation in the remainder of the noise impacted area.

Several variables must be individually evaluated on the local level to determine an appropriate combination of techniques:

Timing: If major land use development is not expected for some time, the municipality has the luxury of being able to set up incentive zoning (cluster and PUD) programs and to utilize an architectural review board for long range planning. Conversely, the threat of extensive rapid development may limit the municipal choice to such things as building and health codes which can be quickly implemented and which apply to individual construction sites even after subdivision layouts have been planned.

Existing Development: If there is no existing development in the area, the choice of physical and administrative techniques is quite wide. If, however, the area is partially developed, it may be exempt from zoning or subdivision control and it may be beyond the scope of any scheme such as planned unit development or acoustical site planning that requires coordinated development of major areas.

Physical Techniques Desired: Some physical techniques such as acoustical subdivision design are not within the scope of some administrative techniques such as building codes. If a particular physical solution is desired, an appropriate administrative technique must be chosen.

Degree of Control Desired: Some administrative techniques such as municipal ownership are absolute controls. Other techniques, such as educational services, incentive zoning, and financial incentives are voluntary. In situations where a most desired administrative technique such as incentive zoning might not always be sufficiently strong, desired control can be assured by having an additional control such as health codes which could be used where necessary.

Financial Considerations: The cost of municipal acquisition of land, and the cost of adopting and enforcing municipal regulations can be significant and must be considered in determining which administrative techniques are to be employed. Other relevant financial considerations are the future tax base and the future demand for municipal services. Both of these, which vary depending on how the land is developed and used, are influenced by the noise compatibility land use control strategy chosen.

Administrative Structure of Local Government: Any administrative technique can only be effective if there is a willingness and a capability within the municipality’s governmental structure to actually administer the technique.

The Local Political Situation: If the local legislative body will not adopt a desired regulation, or if it will not vote funds for land purchase or administrative costs, the desired administrative technique—regulation or purchase—is impossible. Likewise, strong opposition by local officials can hamper any attempt to effectively enforce existing regulations.

Applicability Under State Law: If a technique is not legal under state law, it cannot be considered as a valid noise compatible land use control.

| Administrative Technique | Physical Result | Situations Where Most Applicable | Effectiveness | Cost to the Municipality | Enforcement Mechanism | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zoning to Exclude Typically Incompatible Land Uses | Prevention of Incompatible Land Use | Where Demand for Typically Compatible Land Uses is Significant | High | Insignificant if Zoning Exists | Motel | May Make Land Worthless |

| Zoning to Require Buffer Strips | Buffer Strips | Where Land Values and/or Lot Sizes Permit | High | Note 1 | Easy to Implement in Low Density Areas | |

| Zoning to Require Berms and Barriers | Path Disruption | Where Other Physical Techniques are Not Practical | Varies with Terrain | Notes 1, 2, & 3 | Often not Aesthetically Desirable | |

| Zoning to Limit Building height | Path Disruption | When Terrain Makes this Technique Effective | Varies with Terrain | Note 1 | Effective in Limited Situations | |

| Zoning to Require Acoustical Building Techniques | Insulation, Isolation, Absorption | Where Other Measures are Inadequate | High for Interiors, Low for Exteriors | Notes 1, 2, & 3 | Can Cause Unnecessary Building Costs | |

| Zoning to Allow Cluster or Planned Unit Development | Buffer Strips, Site Design, Path Disruption | Where Large Undeveloped Areas Exist | High | Additional Review Procedure | Approval Procedure | Significant Potential Benefits, but Can be Misused |

| Subdivision Control Law | Buffers, Berms, Barriers, Site Design, Path Disruption | Where Large Developments Rather Than Individual Buildings are Anticipated | High | Insignificant if Subdivision Control Mechanism Already Exists | Notes 1 & 2 | Not Always Applicable |

| Building Codes | Insulation, Isolation, Absorption | Where Individual Lots Are Being Developed | High for Interiors, Low for Exteriors | Insignificant if Building Code Enforcement Already Exists | Notes 1 & 2 | Limited to Few Physical Techniques |

| Health Codes | Most Techniques | Anywhere State Laws Permit | High | Insignificant Addition to Present Health Department Costs | Varies | Highly Effective |

| Special Permit Requirements | Most Techniques | Anywhere That the Permit Granting System Exists or Can Be Started | High | Limited Cost if Special Permit Mechanism Already Exists | Note 1 | Site Specific Analysis for Each Case |

| Environmental Impact Statements | Most Techniques | Anywhere Legal Under State Law | Varies | Varies with Enforcement Mechanisms | Varies | Comprehensive |

| Municipal Purchase of the Land | Buffer Strips, Prevention of Incompatible Land Use | Where Development Pressures Make Less Absolute Measures Inadequate | High | High | Possession | Can be Undesirable Policy for Municipality |

| Other Municipal Acquisition of Land | Buffer Strips, Prevention of Incompatible Land Use | Where Possible | High | Often Insignificant | Possession | Effective |

| Partial Ownership Easements and conservation | Buffer Strips, Prevention of Incompatible Land Use | Where Possible at Low Cost | High | Often Insignificant | Possession | Effective and Often Inexpensive |

| Property Tax Incentives | Prevention of Incompatible Land Use | Where Tax Pressures Exist on Owners of Undeveloped Land | Varies with Response | Varies | Incentive | Easy to Implement, Inexpensive |

| Relaxation of Municipal Codes as a Financial Incentive | Most Techniques | Only Where Code Enforcement can be Relaxed Without Negative Side Effects | Varies | Insignificant | Incentive | Inexpensive |

| Architectural Review Boards | Most Techniques | Where Appropriate Ability Exists on the Municipal Staff | Low; Dependent on Enforcement Mechanism | Often Insignificant; Depends on Administration | Varies | Site Specific Analysis for Each Case |

| Municipal Design Services | Most Techniques | Anywhere | Low | Insignificant | Information; Public Pressure | Very Expensive |

Note 1: Denial of Building or Special Permits

Note 2: Occupancy Permits

Note 3: Performance Bond

1 Under cumulative zoning, zones are ranked in some (high to low use) sequence such as heavy industrial, light industrial commercial, multi-family residential, single family residential. Any use permitted in a low use zone, such as a single family residential, is automatically permitted in higher use zones, such as heavy industrial, but the reverse is not true. Noncumulative zoning does not automatically permit uses other than those specifically allowed in a given zone.

2 The provisions for plantings in this model ordinance are primarily intended to ensure that the buffer is aesthetically acceptable in addition to providing the desired distance between the noise source and the land uses.

3 US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Departmental Circular 1390.2, Noise Abatement and Control: Departmental Policy, Implementation Responsibilities, and Standards (Washington, D.C., August 4, 1971).

4 The numbers used in all the sample codes are only illustrative and not meant as recommended levels. Local evaluation is needed to set appropriate levels for individual communities.

5 Any other local official could be chosen in place of the building inspector if local conditions so dictate.

6 Occupancy permits are discussed later in this section.

7 Orange County uses HUD Technical Bulletin TE/NA 171 for all noise level evaluation except in relation to barriers when it uses HUD Technical Bulletin TE/NA 172.

8 Noise standards within sleeping quarters were taken from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Departmental Circular 1390.2. Noise Abatement and Control: Departmental Policy, Implementation Responsibilities and Standards. August, 1971.

9 The “Board” can be any municipal official or agency that is appropriate under local circumstance.

10 These standards are meant as examples. As in other sample regulations, they must be adapted to local conditions and preferences.

11 Available from state highway department data.