Publication #: FHWA-HEP-09-015 | JANUARY 2009

Prepared for the

U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

Prepared by

Wilbur Smith Associates

and S.R. Kale Consulting LLC

Question. What levels of public sector officials and private sector representatives should be involved in freight stakeholder groups?

Answer. For major initiatives such as transportation plans, the public sector may want to seek involvement from high level representatives of businesses and associations. Public agencies may want to involve high level managers if they are seeking high level private sector representatives. For lesser initiatives, planning staff, lower level agency managers, and lower level private sector managers or staff may be appropriate.

This section of the guidebook discusses freight stakeholder groups at the federal, state, and regional levels; provides information on missions, purposes, objectives, and other guidance statements for existing freight stakeholder groups; summarizes reasons for and against working with freight stakeholder groups; and identifies organizations to consider for freight stakeholder group membership along with ideas about roles and responsibilities of the members. Where applicable, examples from existing stakeholder groups are used for illustration. The section concludes by outlining potential public and private sector challenges and issues relating to freight stakeholder groups.

Guidebook users are reminded that federal legislation does not require state transportation agencies or MPOs to start and maintain stakeholder advisory groups. Some jurisdictions, however, have found that such groups provide valuable input as part of the state or regional public involvement process for transportation planning and programming.

Freight stakeholder groups are typically categorized as boards, coalitions, committees, councils, partnerships, or task forces. These groups are established at national, regional, state, metropolitan, and local levels.

The Freight Stakeholders Coalition, administered through the American Association of Port Authorities, is a national freight advisory group. The coalition's mission is to represent "shippers and public and private transportation providers working together to support policies to promote freight mobility in the United States." One of the coalition's major activities has been to develop a nine-point Freight Stakeholders TEA-21 Reauthorization Agenda. Among the nine points was a proposal to "form a national freight industry advisory group pursuant to the Federal Advisory Committee Act to provide industry input to USDOT." This proposal was not included in SAFETEA-LU legislation but may be reconsidered during reauthorization discussions for future surface transportation funding legislation. See Appendix 3 for details about the coalition's proposal. More information about the coalition is available at: http://www.freightstakeholders.org.

National-level advisory groups also include two commissions established in SAFETEA-LU: the National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission (http://www.transportationfortomorrow.org/) and the National Surface Transportation Infrastructure Financing Commission (http://financecommission.dot.gov/index.htm). SAFETEA-LU requires both commissions to obtain input from freight providers to help address policy, financing, and infrastructure financing needs of the surface transportation system, including its freight components.

Regional stakeholder groups have been established to coordinate and advocate for improvements in support of people and goods movement. Examples include the Mississippi Valley Freight Coalition, the I-95 Corridor Coalition, and the West Coast Corridor Coalition. The Mississippi Valley Freight Coalition is a 10-state organization that cooperates in the planning, operation, preservation, and improvement of transportation infrastructure in the central and northern Mississippi Valley region (http://www.mississippivalleyfreight.org/). The I-95 Corridor Coalition is a partnership of transportation agencies and related organizations to accelerate improvements for people and goods movement from Florida to Maine (http://www.i95coalition.net/i95/). The West Coast Corridor Coalition advocates for solutions to transportation system challenges in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and California by developing and supporting projects of corridor significance, sharing best practices, encouraging joint efforts and cooperation, and advocating for funding of transportation system improvements in the region (http://www.sandag.org/index.asp?projectid=315&fuseaction=projects.detail).

Question. Should a freight stakeholder group be administered formally or informally? What are the characteristics of formal versus informal freight stakeholder groups?

Answer. State or metropolitan legislators, boards, commissions, or administrators will decide whether stakeholder groups will be formal or informal. A formal group is one that has legislation, bylaws, or similar guidance governing the group's responsibilities, membership, and so forth. An informal group has less formal guidance. Formal groups may be formed when decision-makers want to formally commit to obtaining input from freight stakeholders. Sometimes the freight stakeholders work with decision-makers to influence the type of formal arrangement developed.

Several states have freight stakeholder groups or advisory committees. In a 2007 AASHTO survey, about 25 percent of responding states reported engaging the private sector through FACs. In a 2008 AASHTO survey conducted in support of this guidebook, about 35 percent of state transportation agency respondents reported having standing committees or freight advisory committees for obtaining input from the private sector. Among the states that in the past or currently have freight stakeholder groups are California, Colorado, Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington. Additionally, in several states, modal freight stakeholder groups (e.g., for rail) provide input to transportation agencies.

At the metropolitan level, the percentage of MPOs with freight stakeholder groups appears to be similar to the percentage of states with stakeholder groups such as a freight advisory committee. About 18 percent of respondents to a 2003 Association of Metropolitan Planning Organizations (AMPO) survey reported having a FAC. In a 2007 survey by the FHWA, 30 percent of respondents reporting having formal arrangements for communicating with freight stakeholders. In a 2008 AMPO survey conducted in support of this guidebook, about 40 percent of metropolitan planning organization respondents reported having standing committees or freight advisory committees for obtaining input from the private sector. Several MPO freight stakeholder groups have operated for more than 10 years; these include the Goods Movement Task Force of the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, the Intermodal Advisory Task Force (now the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning Freight Committee), and the Freight Mobility Round Table of the Puget Sound Regional Council.

Several cities, including Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon, have freight stakeholder groups. The Seattle Freight Advisory Committee, established in 2002, makes recommendations, supports city implementation of regional planning initiatives, and serves as a forum for exchange between stakeholders and government agency staff on freight mobility transportation improvements, problem identification, ideas for solutions, and funding opportunities (http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/fmac.htm).

The Portland Freight Committee, established in 2003, advises the city's Office of Transportation and City Council on issues related to freight mobility. Its mission is to support and enhance the economy of the City of Portland by advancing a balanced and well-managed multimodal freight network (http://www.portlandonline.com/TRANSPORTATION/index.cfm?a=86660&c=38846).

Mission, Purpose, Objectives, and Other Guidance for Freight Stakeholder Groups

State and regional freight stakeholder groups provide input to transportation agencies, transportation commissions, and other groups about concerns, needs, priorities, and other issues affecting freight mobility. The issues often include capacity, congestion, cost, environmental concerns, financing, infrastructure needs, land use, mobility, rates, regulations, reliability, safety, and security.

Question. Who or what organizations should be represented in a freight stakeholder group?

Answer. At a minimum, freight shippers and carriers or transportation providers should be represented.

State freight stakeholder groups often adopt formal language to guide their activities. Guidance language can take several forms such as mission statements, purposes, goals, objectives, and key roles. Table 3 shows guidance language for freight stakeholder groups in Colorado, Minnesota, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington. Key themes include:

Advise DOTs, transportation commissions, and legislatures on freight issues, policies, planning processes, priorities, projects, research, and funding needs

Educate the private sector on public sector planning processes

Serve as a forum for improving the public's understanding of freight's economic importance and needs

The examples in Table 3 illustrate different themes among freight stakeholder groups.

Table 3: Examples of State Freight Stakeholder Group Guidance Statements

Colorado Freight Advisory Council

Objectives

Minnesota Freight Advisory Committee

Objectives

Oregon Freight Advisory Committee

Mission

To advise the Oregon Department of Transportation, Oregon Transportation Commission and Oregon Legislature on priorities, issues, freight mobility projects and funding needs that impact freight mobility and to advocate the importance of a sound freight transportation system to the economic vitality of the State of Oregon.

Source: http://www.oregon.gov/ODOT/TD/TP/docs/ofac/bylaws.pdfVirginia Freight Advisory Committee

Key Roles

Washington State Freight Mobility Strategic Investment Board (FMSIB)

Mission

In Colorado, Minnesota, and Oregon, the groups provide advice for planning, policy, programming, and funding. A major role of the FAC in Virginia is to provide input for a statewide freight study and action plan for implementing recommendations identified in the study. In Washington, the FMSIB proposes policies, projects, corridors, and funding to the legislature to promote strategic investments in the statewide freight transportation system. Additionally, the FMSIB is charged with finding solutions that lessen the impact of freight movement on local communities.

As with state freight stakeholder groups, metropolitan area stakeholder groups are guided by formal language such as statements of mission, purpose, and objectives. Table 4 shows guidance language for freight stakeholder groups in the Atlanta, Baltimore, Des Moines, Philadelphia, and Puget Sound (Washington State) metropolitan areas. Key themes in the guidance language are:

Table 4: Examples of Metropolitan Freight Stakeholder Group Guidance Statements

Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC) Freight Advisory Task Force

Objectives

Baltimore Metropolitan Council (BMC) Freight Movement Task Force

To provide the public and the freight movement community a voice in the regional transportation planning process. The FMTF is a forum for Baltimore region freight stakeholders to share information and discuss motor truck, rail, air, and waterway concerns.

Source: http://www.baltometro.org/content/view/351/277/Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) Goods Movement Task Force

Purpose

Maximize the Delaware Valley's position in the global economy by promoting local freight operations and implementing a regional goods movement strategy.

Objectives

Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (DMAMPO) Freight Roundtable

Mission

To work with the public and the private sector to maximize the Des Moines metropolitan area's, central Iowa's, and Iowa's economic opportunity through development of and advocacy for an efficient transportation system to promote economic development and trade in the North American trade corridor centered on I-35/I-29 and connecting Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

Source: http://www.dmampo.org/committees/freight.htmlPuget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) Freight Mobility Roundtable

Mission

To engage leaders in the central Puget Sound region in a public-private partnership for our economy and, as a critical part of this, for the mobility of freight and goods. To provide the freight movement community with a voice, and to advance the region's freight movement in a reliable, multimodal and intermodal, efficient, cost-effective, safe and environmentally responsible manner.

Objectives

A primary reason for public sector agency involvement with a freight stakeholder group is to obtain input on private sector concerns and needs regarding the movement of freight to and from their businesses locally, regionally, nationally, and internationally. A freight stakeholder group provides a forum where private sector representatives can voice their concerns and where they can learn how the public sector decision-making process works for transportation project funding and implementation.

A transportation system that works well for freight movements can support and enhance local economic well-being of residents in the area served by the transportation agency. Obtaining input from freight stakeholder group members helps transportation agencies meet federal legislative direction for state transportation agencies and MPOs to obtain input from freight shippers and providers of freight transportation services when developing long-range transportation plans and transportation improvement programs (see Appendix 2 of this guidebook).

Question. What strategies should a transportation agency employ to keep private sector stakeholders engaged over time in freight planning activities?

Answer. The best way to keep the private sector involved is by showing that their input has been considered in transportation funding decisions and project implementation. This includes the inclusion of freight-related projects in transportation improvement programs and the construction/implementation of projects that address mobility and other concerns of freight stakeholders.

Additionally, NCHRP Report 570, Guidebook for Freight Policy, Planning, and Programming in Small- and Medium-Sized Metropolitan Areas, indicates that private sector participation in freight policy, planning, and programming is important for

Insufficient funding or staff resources are reasons why a state transportation agency or MPO might choose not to work with a freight stakeholder group. Starting and maintaining a stakeholder group requires allocating staff to work with group members on setting and distributing agendas, maintaining mailing lists, and coordinating a variety of related activities. Ideally, the publicagency stakeholder group coordinator understands freight-related issues and can convey this understanding in a manner that resonates with the group's leadership and members.

A transportation agency might decide not to work with a freight stakeholder group if the agency has had difficulties finding private sector representatives willing to devote time and energy to public sector transportation planning activities. Related to this are the difficulties associated with:

Freight stakeholder groups typically include private sector and public sector representatives. Private sector members may include shippers such as manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and other businesses with products to ship; carriers or transportation providers moving products between origins and destinations; logistics companies that provide a variety of services to shippers; and associations representing carriers, transportation providers, or shippers.

Question. To what extent should freight planners seek involvement from the private sector in public-private partnerships?

Answer. Planners may want to seek involvement from the private sector if they are developing public-private partnership language for transportation plans, improvement programs, special studies, and other materials. With the increased interest in public-private partnerships, a number of resources have become available for planners and others to use. Resources include an FHWA web site on public-private partnerships at http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ppp/, and several publications from the U.S. Government Accountability Office and the Congressional Research Service (see the "References Cited in this Guidebook" section

of Appendix 4).

Public sector members may include representatives from federal, state, regional, and local governments. Where navigable waterways are present, freight stakeholder groups may include representatives of port districts or authorities. Chambers of commerce or economic development organizations sometimes are represented. Other represented organizations may include universities and consulting companies.

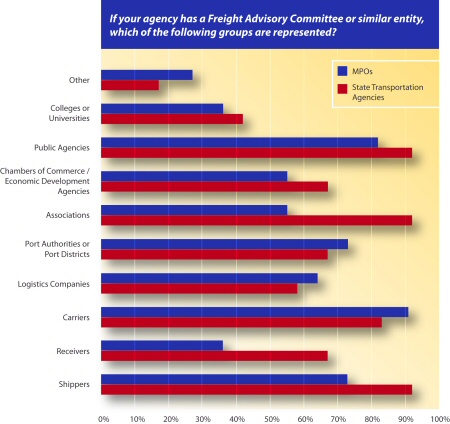

Figure 6 shows the types of organizations represented in the membership of freight stakeholder groups at state transportation agencies and MPOs responding to the 2008 AASHTO and AMPO surveys referenced in Section 2 of this guidebook.

For state transportation agencies, the following entities are most represented: associations, public agencies, shippers, and carriers. For MPOs, the most represented entities are carriers, public agencies, port authorities/port districts, and shippers. Colleges and universities are among the entities least represented for state agency and MPO freight stakeholder groups.

Provisions for membership in freight stakeholder groups may be informal or formal. With informal groups, membership often is open to a variety of organizations interested in freight transportation. For example, membership in the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission's Goods Movement Task Force is "open to all trucking, railroad, port, airport, shipper, freight forwarder, economic development, and member government representatives" (http://www.dvrpc.org/freight/dvgmtf.htm).

In a few jurisdictions, more formal arrangements are stipulated by agency or legislative directive. The Colorado Freight Advisory Council has an operating charter stipulating number and type of organizations represented on the council. Legislation authorizing the Oregon Freight Advisory Committee (OFAC) stipulates that "committee membership shall include, but not be limited to, representatives from the shipping and carrier industries, the state, local governments and ports, including the Port of Portland."

OFAC bylaws (http://www.oregon.gov/ODOT/TD/TP/docs/ofac/bylaws.pdf) further stipulate the maximum committee size (32) and provisions for general and associate members. In Washington State, the Revised Code of Washington details provisions for membership on the Freight Mobility Strategic Investment Board.

Statements of mission, purpose, objectives, and the like, as shown in Tables 3 and 4, provide general guidance about roles and responsibilities of freight stakeholder groups. The roles and responsibilities are carried out when the stakeholder groups provide input on state transportation agency and MPO initiatives, such as transportation plans and improvement programs, special studies, and needs/project identification and prioritization.

Figure 6: Organizations Represented on Freight Stakeholder Groups

*Warehouses, consultants, governor's office, energy company, truck stop consortium, AAA, developers, airport

Source: 2008 AASHTO and AMPO Surveys

Question. What factors should be considered in deciding whether a freight stakeholder group should be on-going or ad hoc?

Answer. An important consideration is whether the agency has sufficient staff and other resources to maintain a freight stakeholder group over time. Another consideration is whether stakeholder group members are willing and available to engage in freight planning activities over time.

Roles and responsibilities are more formal in a few jurisdictions. This has occurred primarily through legislative action at the state level, and is formalized in statute. In Washington, state law specifies "duties" of the Freight Mobility Strategic Investment Board (http://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=47.06A.020). These include what the board "shall" do and what the board "may" do. The FMSIB also has developed a set of bylaws (http://www.fmsib.wa.gov/documents/bylaws918.pdf) further clarifying its duties and functions.

In Oregon, state law directs the statewide freight advisory committee to (http://www.oregon.gov/ODOT/TD/TP/docs/ofac/ors366.pdf)

Additionally, the committee "may make recommendations for freight mobility projects to the commission. In making the recommendations, the committee shall give priority to multimodal projects."

Probably the biggest challenge for the public sector is finding the resources to fund and staff a position to work with the freight stakeholder group. Managing a freight stakeholder group requires a significant amount of staff time depending on a variety of factors such as

Frequency of meetings and number of stakeholder group initiatives

Amount of coordination needed between staff and the freight stakeholder group chair and other members (e.g., chairs of stakeholder group subcommittees)

Amount of work staff does on behalf of the stakeholder group (e.g., finding meeting rooms, helping set agendas, distributing meeting notices and agendas, writing meeting minutes, maintaining stakeholder group files, contacting guest speakers, developing materials for stakeholder group review, and writing draft documents such as letters, memorandums, and reports on behalf of the stakeholder group)

Question. Does population size of the state or metropolitan area matter when deciding whether or not to start and maintain a freight stakeholder group?

Answer. Transportation agencies in states and metropolitan areas with relatively greater populations generally have more resources than agencies in states and metropolitan areas with smaller populations. Relatively more resources may mean that the agency can devote relatively more effort to engaging the private sector, including through freight stakeholder groups.

At a minimum, 0.25 of a staff position is needed for managing stakeholder group activities, though requirements could be greater depending on the specific circumstances associated with the stakeholder group. Managing stakeholder group activities may require time from executive-level staff as well as from clerical and other staff.

Another issue is whether freight stakeholder group members believe the public sector is able to deliver results that are meaningful to the private sector. This may require a sustained relationship between the public sector and the stakeholder group due to the long time periods that often are needed to implement public sector transportation projects. Ideally, in the near term, public sector representatives can respond to the private sector's more immediate needs, however defined, and maintain the stakeholder group as a forum in which participants' comfort levels grow over time.

If the public agency does not have the resources to maintain a freight stakeholder group over time, then it should at a minimum devote enough resources to insure that private sector representatives provide input into state and regional transportation plans and improvement programs. This may mean establishing freight stakeholder groups on an ad hoc basis whereby group members provide input during the development of plans and improvement programs, then disband once the input has been provided. Or it may mean identifying stakeholders to serve with other stakeholders on policy-level, technical, or citizens' advisory committees for plans, improvement programs, or special studies.

Another challenge may be finding enough private sector representatives to serve on freight stakeholder groups. Many stakeholders do not have much time, energy, or patience for serving on public sector committees, especially if the stakeholders do not see results that address their concerns. This is true for longer-duration freight stakeholder groups as well as those that are formed for specific purposes such as transportation plans or improvement programs. And it's important for the public sector to show appreciation for private sector involvement, especially to people or businesses that participate on stakeholder committees over long periods of time.