U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-15-008 Date: July 2016 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-15-008 Date: July 2016 |

This chapter presents findings from the team’s extensive review of the literature and the survey conducted by the project team of State transportation department and LPA staff. The literature review included FHWA and State transportation department process reviews, prior research related to LPAs, current LPA guidance manuals, and FHWA/State transportation department stewardship agreements. Both State transportation department and LPA staff were surveyed to capture the different perspectives regarding QA for LAPs.

Also noted in the introduction, national reviews of LAPs conducted by FHWA in 2006 and the OIG from November 2009 through April 2011 revealed significant shortcomings in the efforts of LPAs to properly administer Federal-aid projects and in the role and effectiveness of oversight activities performed by the FHWA Division Offices and the State transportation departments to ensure LPA compliance with Federal requirements.

To gain further insight into possible areas of weakness in how LPAs conduct QA and in how State transportation departments oversee these LPA activities, the team conducted a comprehensive literature review. The primary resources consulted included the following:

To capture any changes or improvements made to LPA programs as a result of the 2006 National LPA Review, the team contacted various FHWA Division Offices and State transportation departments to identify and collect process reviews and audits of LPA programs performed between 2006 and 2012. Particular emphasis was placed on obtaining reports that addressed construction, inspection, and/or materials QA on federally funded LPA projects.

The team reviewed the reports to identify general trends in QA practices, as well as possible issues to investigate and agencies to explore further in phase II. Appendix E summarizes in a tabular form those reports that were identified as relevant to this research.

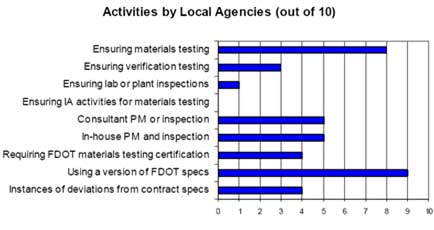

As suggested by the summaries provided in appendix E, the level of detail in the reports related to the topic of QA varied, but a number of reports were flagged for follow-up in phase II of the project. For example, the FHWA Florida Division report on construction oversight of off-State highway system (SHS) LPA projects contains some particularly telling statistics presented in figure 2 regarding the inconsistency or variability in the level of QA activities being conducted by LPAs in Florida.(11)

Figure 2. Bar Graph. Summary of interviews with 10 local agencies in Florida (from the 2008 LAP IIIB Review Report).

Such trends were also observed in a number of other reviews conducted across the Nation. In May 2007, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), jointly with the FHWA California Division Office, conducted a QA process review of five local agencies: City of Redlands, County of Los Angeles, County of Solano, County of San Joaquin, and County of Sacramento.(12) The findings of this review were published in September 2007 and noted that “in general, the sampling, testing, and IA efforts on local agency projects need improvement.” Specific observations included the following:

More recently, Caltrans has also been conducting and publishing quarterly reviews of LPA-led American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA) projects.(13) As of March 15, 2011, approximately 880 local agency ARRA projects were authorized in California, 95 percent of which received either joint or Caltrans reviews. In the report published for the fourth quarter of 2011, “frequency of sampling/testing deficient” and “sampler’s/tester’s certifications incomplete” were included among the top 10 observed deficiencies. Other identified noncompliance items related to construction QA included the following:

The general conclusions drawn from all review reports can be summarized into the following six broad categories:

Reviews conducted by the FHWA PMIT team that were related in some manner to the subject of LPAs or QA were downloaded from the FHWA PMIT database. There were 53 observations and recommendations from the PMIT team that related to the research topic. The key issues found are reported, along with their frequency of occurrence, in table 3. The most widespread issue concerned deficiencies in the project files, under the broader topic of contract administration, particularly related to Buy America provisions.

Table 3. Summary of key issues found in the FHWA PMIT audits.

| Issue Identified Through Audit | Frequency of Occurrence (of 53 observations) (percent) |

|---|---|

| Contract administration or file deficiencies (especially Buy America) | 20 |

| Lack of, or not following, QA procedures or specifications | 16 |

| Qualified/certified materials testing personnel not documented | 16 |

| Materials certification (improper or lacking) | 14 |

| Lack of (or insufficient) sampling frequency | 14 |

| Insufficient inspection frequency, number of inspections, or inspection detail | 13 |

| Acceptance of failed materials | 5 |

| QC/QA not done on Force Account projects | 1 |

The PMIT audits also observed three instances of good practices, as summarized in table 4, which generally related to the proper application of construction QA procedures.

Table 4. Good practices as noted in the FHWA PMIT audits

| Good Practice as Identified Through Audit | State |

|---|---|

| Review of several projects indicated that proper testing and payment of materials are performed by LPAs. For example, somefailing compressive strength tests on one city project resulted in the appropriate execution of penalties. The LPA also properly assessed liquidated damages when the contractor did not complete the work in the allotted number of calendar days. | Missouri |

| Use of construction checklists by State transportation department district personnel helps to better focus project oversight. | Multiple |

| One LPA developed its version of a contract management system, similar to AASHTO’s SiteManager™, using a wireless network and based on Microsoft® Visual Studio with the specific module entitled Architectural/Civil Inspections. The system allows the inspector to enter pay quantity items in the field on a daily basis. The system is also capable of providing weekly summaries of each pay item incorporated into the project based on the daily reports and generating a monthly pay estimate. | Virginia |

To aid LPAs in addressing the complexities of the Federal-aid project delivery, a three-pronged strategy was implemented under FHWA Every Day Counts (EDC) 2.(4) This included stakeholder partnering, certification program, and the use of consultant services flexibilities as follows:

The FHWA EDC 2 Web site includes additional information on benefits of these current LPA practices and current status of their use. It also provides additional resources and tools for LPA projects, including FHWA Essentials for LPAs, and an FHWA LPA Web site.(4)

FHWA has now transitioned to its EDC 3 program. Of the three initiatives, stakeholder partnering continues into EDC 3. This initiative focuses on forming stakeholder committees that include representatives from STAs, LPAs, and FHWA. The purpose of the committee is to improve communication by serving as a platform to launch training and process improvements in Federal-aid project delivery. Stakeholder partnering has the following benefits:

Recent National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Synthesis Reports 414 and 442

A few items highlighted in the 2011 NCHRP Synthesis Report 414, Effective Delivery of Small-Scale Federal-Aid Projects, and the 2013 NCHRP Synthesis Report 442, Practices and Performance Measures for Local Public Agency Federally Funded Highway Projects, were relevant to this research project as follows:(14,15)

WSDOT also developed a conceptual materials risk analysis process in which typical construction materials were examined for the risk of having a material fail to meet specification and the consequences of that material failing to meet a given specification.(17) The result of the study was the development of a risk ranking system for either more or less intensive examination by WSDOT. The following four categories and associated actions were developed:

WSDOT now has a system in place to formally evaluate the risk of materials (failure to meet specification and the consequences of those failures) and to determine the level of assurance needed to accept each construction material. WSDOT is now working on establishing an electronic management system to track the actual performance of a wider variety of materials over the course of their lifecycles.

FHWA Local Agency Review

Construction practices in a handful of local agencies in Florida were reviewed in detail in 2007 by the FHWA Florida Division Office. Some of the better practices employed were summarized and include the following:(14)

NCHRP Synthesis Topic 43-04 (2012) Practices and Performance Measures for Local Public Agency Federally Funded Highway Projects

A few items highlighted in the 2012 NCHRP Synthesis Project 43-04 were relevant to this research project.(18) The findings presented below came from the raw data responses to either the State transportation department or the LPA survey.

State Transportation Department Survey:

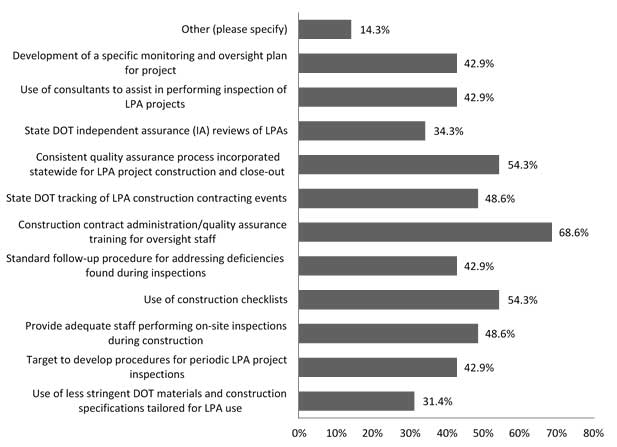

Source: L. McCarthy

Figure 3. Bar Graph. Summary of responses from State transportation departments related to improving LPA oversight during construction (from 2012 NCHRP Synthesis 43-04 DOT Survey).

LPA Survey:

Table 5. Summary of responses from LPAs related to improving LPA oversight during construction (from NCHRP Synthesis 43-04, 2012).(18)

| Activity Reported | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|

| Application of QA to all federally funded projects | 26 of 40 |

| Consistent procedure for periodic inspections of your federally funded projects | 29 of 40 |

| Use of construction checklists | 26 of 40 |

| Standard follow-up procedure for addressing deficiencies found during inspections | 22 of 40 |

| Formal tracking of construction contracting events (e.g., subcontracts, materials certification test results, etc.), with updates to the State transportation department | 28 of 40 |

| Use of consultants to assist in more frequent inspection of your projects | 22 of 40 |

Evaluation of the Wisconsin Department of Transportation Local Program Management Consultant Program

In 2006, in response to a number of shortcomings cited by FHWA regarding the Wisconsin Department of Transportation’s (WisDOT) management of its local program (e.g., inadequate staffing and resources, lack of proper inspection, poor QC, inconsistency in State oversight, deficiencies in documentation, etc.), WisDOT began to use management consultants (MC) to manage its Federal-Aid Local Program statewide.

Under the MC program model, WisDOT delegates direct project oversight on LPA projects to an MC, who reports to a WisDOT Regional Project Manager. The MCs provide reviews and spot-checks for preliminary design, environmental documentation, final design, and construction management. FHWA treats MC oversight as WisDOT oversight.

A February 2012 evaluation of the effectiveness of the MC program over the 6-year history of its statewide implementation revealed the following(19):

AASHTO 2013 Subcommittee on Construction LPA Oversight Survey Results

The AASHTO Subcommittee on Construction conducted a survey in 2013 addressing State transportation department oversight of local agency construction projects. One question addressed State transportation department oversight of LPA project phases. Regarding the construction administration phase, the majority of State transportation departments performed construction administration (70 percent); however, some reported that under certain conditions, certified LPAs share or take on more of the responsibility for construction oversight. The following are examples of the responses(20):

In a corollary question, AASHTO asked what entity (i.e., State transportation department, LPA, or consultants) typically performs construction administration and materials QA. The responses indicated that in some cases, the State transportation department or the LPA performs QA, but the majority of respondents (70 percent) indicated that consultants were used in all phases of a project, including construction inspection services.

In a follow-up question AASHTO asked whether State transportation departments have implemented certification, training, experience, or licensing requirements for LPAs and their consultants. The responses indicated that fewer than half of the responding agencies had certification requirements. Also certification could refer to general LPA qualification or certifications to perform specific functions (i.e., asphalt testing). Examples include the following:

Thirty-nine State transportation departments maintain Web sites related to their LPA assistance programs. The team accessed each of these Web sites and collected any guidance manuals and procedural information related to construction administration and QA activities.

Because several of the findings reported in the process reviews summarized in appendix G revealed shortcomings in the guidance provided to LPAs, the team performed a content analysis of the guidance manuals.

A review of the manuals collected, as summarized in appendix H, revealed extreme differences in the breadth and depth of information provided to assist the LPAs. Several State transportation departments focus primarily on preconstruction issues such as project selection, utility and railroad coordination, and ROW acquisition, with very little guidance related to construction administration and QA.

Other State transportation departments have made a considerable effort to provide guidance on how to perform materials testing and construction inspection and document the results. For example, the Maine Department of Transportation (MaineDOT) publishes a manual and reference guide on both construction administration and construction documentation that provide LPAs with an overview of the construction oversight and documentation processes that they must follow to ensure work is performed according to the contract plans and specifications and Federal and State requirements. In addition to such guidance, the MaineDOT Materials Section also prepares Minimum Testing Requirements to specify the frequencies and types of tests that are to be done on materials used on a specific project.

Similarly, in its Quality Assurance Program (QAP) Manual for Use by Local Agencies, Caltrans defines the required elements of a QAP, addressing both acceptance and IA. Instruction is provided on maintaining acceptance testing records and materials documentation and on developing an IA program (if not requesting Caltrans to provide IA services). Acceptance sampling and testing frequency tables for various materials and project elements are also provided. Details regarding the FHWA/Caltrans process review program are provided as well, alerting LPAs to the types of questions and information sought during these audits.(21)

New Hampshire Department of Transportation (NHDOT) also publishes a separate sampling and testing program guide for LPA-managed Federal-aid projects, requiring such agencies to develop a specific QAP for each project. The LPAs are required to define in their QAPs the quantity of each item in the project that requires sampling and testing; the number of acceptance tests required; an anticipated schedule for testing; the name and contact information for the party conducting the acceptance tests; and the sources of materials, including production plants for ready mix concrete, hot mix asphalt (HMA), precast concrete, and structural steel. Frequency of Sampling and Testing tables are provided for soils, asphalt items, concrete items, and structural steel. For materials not included in these tables, the LPA may base acceptance on the producer’s certification that the material meets the appropriate NHDOT specification or inclusion of the material on the NHDOT Qualified Products List (QPL) and submittal of a Certificate of Compliance.

Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT), in its Local Government Administered Project Manual, perhaps comes the closest to strictly adhering to, and touching upon, the elements required of a QA program under 23 CFR 637.(1) LPAs are repeatedly reminded to perform QA in accordance with the CFR and GDOT’s Sampling, Testing and Inspection Manual, and to ensure that testing is completed by laboratories accredited through the AASHTO Accreditation Program, using testers certified by GDOT. The certified technicians that perform sampling and testing on the project must also submit to GDOT’s IA program.(22)

A review was conducted to assess the content of current FHWA/State transportation department S&O agreements. Each State’s S&O agreement is meant to set the pace for the Federal-aid program, similar to a “contract” in spelling out expectations and responsibilities.

The purpose of this review was to identify the extent to which QA of the LPA program, construction oversight, and materials QA are being addressed in the overarching agreement between a given FHWA Division and its State transportation department. Sections of the agreements that could be related to LPA-administered projects were assigned a rating (good, limited, and vague) in terms of their specificity and emphasis on materials QA and construction oversight. Appendix I summarizes the results of a review of 13 FHWA/State transportation department S&O agreements.

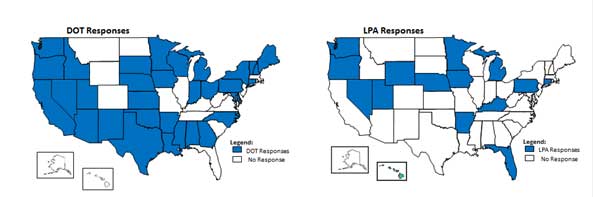

Surveys were developed and distributed to all State transportation departments, and responses were returned by 34 States and the District of Columbia. A similar survey was distributed to LPAs, in some cases from names suggested by the respondents to the State transportation department survey, and 33 agencies from 14 different States across the Nation provided responses. Maps of the States in which responses were provided by the State transportation department and LPA surveys and interviews are presented in figure 4.

Figure 4. Map. Geographical distribution of survey responses by agencies.

Given the distinct roles and responsibilities assumed by State transportation department and LPA representatives in the delivery of a LAP, separate surveys were developed so that questions could be tailored as necessary to align with the State transportation department and LPA perspectives. For example, whereas the State transportation department survey primarily focused on the State transportation department’s oversight of LPA programs, the LPA survey addressed the LPA’s construction program size, Federal-aid project types, use of in-house versus consultant staff for QA, and the existence of internal QA guidelines. Both surveys asked respondents to identify the levels of construction QA (i.e., levels of inspection, testing) and oversight (in the case of the State transportation departments) applied to various project types. In addition, surveys asked respondents to identify practices that have been successfully applied to mitigate QA issues. Preliminary results from these surveys are summarized in the following subsection.

To capture multiple perspectives within the State transportation department, email invitations were sent to State LPA coordinators as well as to construction and materials engineers. Survey distribution and response statistics are as follows:

Results from key survey questions are summarized in the following subsections and documented in appendix G with comments. Unless otherwise noted, when multiple surveys were received from a single State transportation department, a composite answer was generated to reflect the collective response of the State transportation department. Raw State transportation department survey results in Microsoft® Excel have also been provided separately in appendix G.

The survey results were analyzed to identify any discernible trends regarding program size, project types, and training and oversight resources, particularly in terms of challenges and best practices associated with materials and construction QA. Findings of this analysis include the following:

Organizational Structure/Certification

Training

Training was identified in past process reviews as a best practice. Of 48 responses, 28 State transportation departments indicated that specific training was provided to their staff (or consultants) on how to oversee the construction QA performed on LPA projects. Twenty-two State transportation departments indicated that training is provided to LPA staff on how to implement the QA standards for Federal-aid projects.

State Transportation Department Oversight of LPAs

The primary means that State transportation departments use to assure that LPAs are complying with QA standards and specifications range from onsite field inspections to project reviews or audits by the State transportation department and/or FHWA, which were included in 28 and 29responses, respectively (of 48 responses). In comparison, verification testing was cited in only 16 responses and was more commonly attributed to State transportation departments that engage consultants to assist with the LPA oversight process.

Oversight Staff: The people performing inspections on LPA projects vary by State transportation department, but in many States, they are a mixture of consultant and State transportation department Central Office or District Office staff. In States with relatively small local programs, such as Delaware and Oklahoma, the State transportation department staff generally directly administers the construction phase of projects on behalf of the LPAs. In such States, the risk profile of LPA projects is therefore the same as for the State transportation department projects.

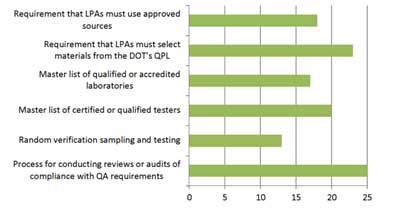

QA Oversight Procedures: In response to being asked what QA procedures State transportation departments maintain or what activities they conducted to oversee LPAs, the majority of the State transportation departments responding cited reviews/audits, maintenance of QPLs, and lists of accredited laboratories and qualified testers. For example, LPAs must select materials from the State transportation department QPL or master list of qualified or accredited laboratories, or use approved sources (e.g., quarries) as noted in figure 5.

Figure 5. Bar Graph. Summary of QA oversight practices.

However, where State transportation departments certify LPAs, these certified LPAs may develop their own QA procedures. The procedures the State transportation department would undertake would vary depending on the LPA-approved program specifics. Twenty State transportation departments (of 48responding) indicated that they allowed LPAs to use their own specifications or standards for materials and construction QA. Several respondents further clarified in the comments section to the survey that the State transportation department would need to first review and approve LPA-generated specifications or QA programs.

Nearly half of the departments of transportation account for compliance with QA standards in the overall estimated cost of an LPA project. When compliance is not met, the LPAs often must find the additional funds to complete the necessary testing to comply with QA standards.

Specifications: In 30 percent of the States that responded, the LPAs are permitted to use their own specifications or standards (with prior State transportation department review and approval) for activities related to materials and construction QA. Twenty State transportation departments (of 48 responding) indicated that they allowed LPAs to use their own specifications or standards for materials and construction QA. Several respondents further clarified in the comments section to the survey that the State transportation department would need to first review and approve LPA-generated specifications or QA programs.

Independent Assurance: In more than half of the responses, the State transportation department’s IA program covers LPA testers and equipment on federally funded LPA projects, and in States where it is not routinely covered, the State transportation departments provide assistance when possible. The approach by the responding State transportation departments to IA was split equally between a system-based and a project-based approach on LPA projects.

Twenty-four of 31 State transportation departments indicated that their IA program covered the LPA’s testers and equipment. Conversely, 8 of 33 State transportation departments indicated that LPAs could develop their own IA program (either by choice or if the State transportation department did not extend its IA program to the LPA). However, as noted in some survey comments and as further clarified during interview discussions, complying with Federal IA requirements for LPA projects is recognized as a challenge, particularly for smaller LPAs.

For example, in New Hampshire, the system-based IA and QA approach includes acceptance testing for the federally funded LPA projects that is similar to the State transportation department projects because the same testing consultants are doing both levels of projects. The difference between the State transportation department and LPA projects is that the IA includes fewer material quantities for LPA projects.

Sampling and Testing Schedules: In 57 percent of the States, the State transportation department prepares the materials sampling and testing schedule for LPA-administered Federal-aid projects or requires that the LPA must use the State transportation department’s minimum sampling and testing guide, which indicates the testing frequencies.

Eighteen State transportation departments (of 26 respondents) indicated that they prepared the materials sampling and testing scheduled for LPA-administered projects. However, of the eight State transportation departments that indicated that they did not prepare the sampling and testing schedule for the LPA, three further clarified that they reviewed and approved the LPA-generated schedule.

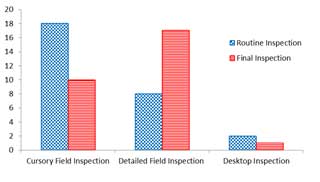

Inspection Level of Effort: The State transportation departments were queried about what their level of effort was for the inspection of materials and construction on federally funded LPA projects. For a routine or periodic inspection during construction, State transportation departments were more likely to perform a cursory field inspection, whereas at final inspection, a more detailed field inspection/acceptance was more common (based on 27 responses) and they can be seen in figure 6.

Figure 6. Bar Graph. Routine inspection versus final inspection.

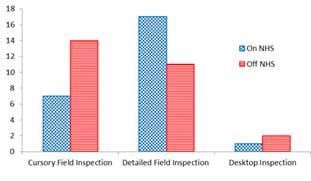

Also, State transportation departments were more likely to conduct detailed field inspection on an LPA project located on the NHS than one that was located off the NHS (based on 27 responses) as seen in figure 7.

Figure 7. Bar Graph. Level of inspection for on- versus off-NHS (SHS).

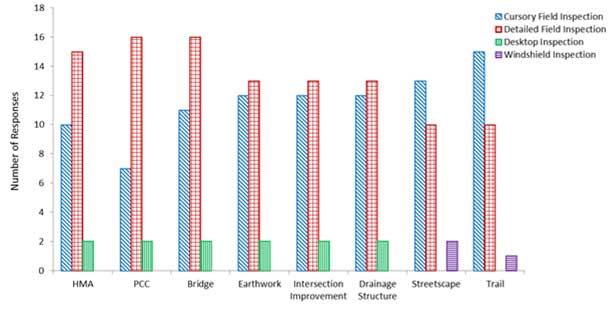

In general, the survey results (based on 31 responses) indicated that the State transportation departments are primarily performing cursory inspections on trail and streetscape projects, while reserving more detailed field inspections for earthwork, pavements, and bridges or structural elements as seen in figure 8.

Figure 8. Bar Graph. Inspection effort based on project type.

Weaknesses in Construction QA

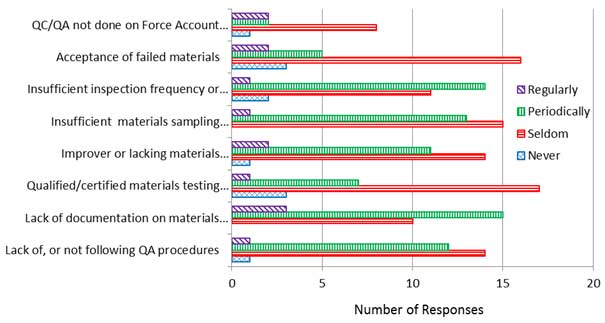

Frequency of QA-Related Issues: In response to how frequently issues regarding materials and construction QA occur on federally funded LPA projects, figure 9 shows that many of the responses stated that issues seldom occurred or only did so periodically. The issues with the highest frequency of occurrence, either regularly or periodically, were lack of QA documentation and insufficient materials sampling/inspection frequency or detail. This response was consistent with the general response received from the interviews of both State transportation departments and LPAs that there was not necessarily an issue with materials and construction quality, but more with the documentation and compliance with contract administrative elements of the construction, including QA documentation and procedures.

Figure 9. Bar Graph. Frequency of issues related to QA.

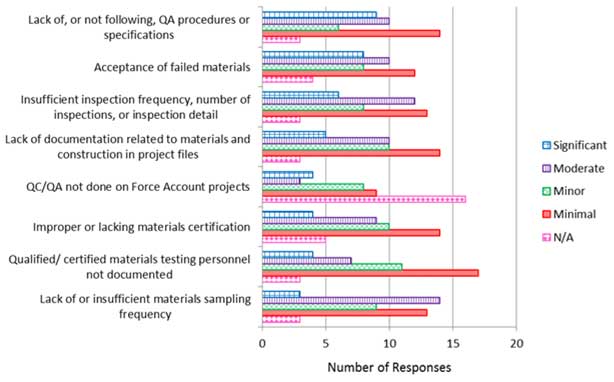

Perceived Significance of QA Issues: Figure 10 presents the relative significance of these issues reported by State transportation department staff. The issues were prioritized (top to bottom) based on the number of responses reporting a significant or moderate impact on QA. The results indicate that the most significant issues from the State transportation department perspective were lack of and/or not following QA procedures, acceptance of failed materials (also interpreted as simply failed materials), insufficient inspection frequency, and lack of QA documentation in the files. It should be noted from the responses that it was as likely that these issues had minor or minimal impacts on quality.

Figure 10. Bar Graph. Perceived impacts of issues from State transportation department perspective.

It was difficult to identify trends in the data for impacts because it appears that the responses to this question were driven in part by a respondent’s role in the organization. Follow-up interviews were conducted with all State transportation departments that rated issues as having significant impacts to obtain more information on how the rating was assigned and the experiences in these States. During interviews, some State transportation department staff, particularly LPA coordinators, stated that the failure to provide required documentation was perceived as a significant impact and could result in loss of Federal funding. Conversely, construction and materials staff cited that not following QA procedures, insufficient testing and inspection, or acceptance of noncompliant materials were the most significant impacts and could also result in FHWA withholding Federal funds on an LPA project.

Best Practices (to Avoid or Mitigate Issues)

The last series of questions asked State transportation department respondents to identify any practices that have been used to improve or mitigate perceived challenges, and rate these practices in terms of their significance for mitigating challenges (e.g., minimal, moderate, or significant). These responses are grouped together and summarized in the following paragraphs.

Training and Certification of State Transportation Department Staff and Certification of LPAs: Training and certification of State transportation department staff and presumably certifying LPA staff for administration and QA oversight was viewed as a moderate to significant practice to mitigate challenges. A significant number of State transportation departments (8 of 22, or 36 percent) cited training and certification as important, particularly when training was provided on an annual or periodic basis. Certification of an LPA (presumably for QA and other purposes) allows the State transportation department to shift administration of the project to the LPA staff or its consultants and reduce the level of State transportation department oversight.

Periodic Meetings and Communication: Conducting preconstruction conferences to explain QA requirements, periodic update meetings during construction, quarterly or annual reviews, and other forms of direct communication between the State transportation department and LPA staff to clarify requirements or changes were cited by several agencies (5 of 22, or 23 percent) as a practice that improves QA, expedites final acceptance, and ensures that administration of an LPA project meets Federal-aid requirements.

Providing the Same QA Oversight of LPAs as for State Transportation Department Projects: Some State transportation departments (4 of 22) reported that providing the same oversight of LPA projects as for State transportation department projects, using State transportation department specifications and QA procedures, was a best practice for QA of federally funded LPA projects. A closer examination of the State transportation departments providing this response revealed that these were departments most often in rural States or smaller programs administering LPAs with fewer resources.

Other: Additional best practices cited by one or more State transportation department included the following:

LPA Survey

The goals of the LPA survey were to identify the levels of construction QA (i.e., levels of inspection, testing) applied to various project types and to determine how the LPA coordinates with the State transportation department to ensure QA requirements are met.

For comparative purposes, questions were also posed to collect information on the LPAs’ construction program size, typical Federal-aid project types, use of in-house versus consultant staff for QA, and the existence of internal QA guidelines.

Survey distribution and response statistics were as follows: The original distribution list included the contact information of 129 LPA representatives that had provided survey input on past research studies. Demonstrating the high level of turnover at LPAs, more than 20 percent of the email invitations immediately bounced back because the email addresses were inactive. Through the State transportation department surveys, an additional 47 LPA contacts were identified.

Thirty-four responses have been received from LPAs. In addition, several LPAs were interviewed in conjunction with State transportation department visits. According to the survey responses, surveys were received from LPAs located in Arkansas (1), Connecticut (1), Florida (10), Hawaii (1), Iowa (2), Kentucky (1), Michigan (1), Minnesota (4), Nebraska (2), Nevada (2), Pennsylvania (1), Oregon (4), Utah (2), Washington (1), and Wyoming (1).

Survey questions are summarized below and documented in appendix J with comments. Raw LPA survey results in Microsoft® Excel have also been submitted separately. Key findings that can be drawn from the LPA surveys received thus far are described in the following subsections.

Program Structure/Size

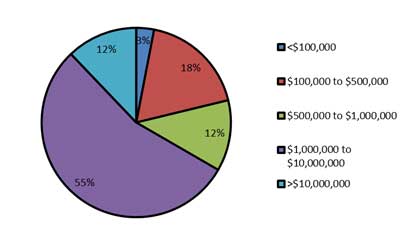

As seen in figure 11, 55 percent of LPAs surveyed had annual construction programs ranging from $1 to $10 million. At the extremes, 3 percent had programs of less than $100,000, and 12 percent reported having programs of more than $10 million. Sixty-six percent of respondents reported that 0 to 30 percent of their construction program was performed using Federal-aid funds. The remaining 34 percent reported that Federal funds comprised 30 to 60 percent or, in a few cases, less than 60 percent of their program.

Figure 11. Pie Chart. Size of LPA programs in dollars.

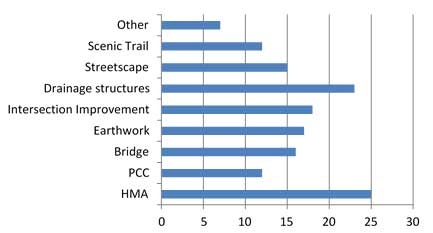

The LPAs reported a wide range of project elements were included in their programs. These include pavements and bridges to intersections, drainage structures, streetscapes, and scenic trails. The majority of LPAs reported using Federal-aid funds for HMA paving projects and drainage structures. Figure 12 shows typical project elements reported by respondents.

Figure 12. Bar Graph. Typical LPA project elements.

Cost of QA

In response to a question regarding the amount of project funds typically dedicated to QA, specifically for QA testing and construction inspection, the responses ranged from 5 to 30 percent, with an average of approximately 10.7 percent. One respondent reported 0 percent, which indicated that QA was performed by State transportation department staff outside the project budget. Most, however, indicated that QA was a component of the project funding and that QA costs were typically higher for federally funded projects. For example, one LPA respondent provided additional detail indicating that QA costs for town-funded projects were typically less than 10 percent of project costs, whereas QA costs for a federally funded project amounted to greater than 30 percent of project funds. Another LPA provided a breakdown of LPA construction engineering and inspection (CEI) costs (15 percent of contract value), contractor QC costs (3 to 5 percent of contract value), and LPA QA costs (25 percent of contractor QC costs or a one to four ratio for QA to QC testing. This indicated that the higher end of the range of reported percentages (i.e., 20 to 30 percent) represented the combination of all cost components, whereas the lower end (i.e., 3 to 7 percent) represented the activities related to testing and acceptance.

LPA QA Practices

The survey responses indicated that the LPAs rely heavily on consultants, with 23 agencies indicating that they retain consultants to perform QA activities. Most of the LPAs retain consultants and testing laboratories that are qualified or certified by the State transportation department. The responses indicate that LPAs seem to be applying the same level of QA (testing and inspection) regardless of project type (e.g., pavement or scenic trail). The LPAs also appear to rely heavily on State transportation department guidance and standards. Twenty‑nine of 32 LPAs defer to the State standards to determine a project’s sampling and testing needs. Fifteen LPAs indicated that they have received training from the State transportation department related to construction QA.

State Transportation Department Involvement in Construction QA

With regard to the level of department of transportation involvement in LPA project QA activities, the LPAs reported that State transportation departments are often involved in IA, final acceptance, verification testing, and inspection. For inspection, the survey results indicated that State transportation department staff may have moderate to major involvement; however, one of the respondents stated that the level of involvement of a State transportation department varies depending on the project type and whether the LPA is a certified agency. For example, an LPA county in Washington State indicated that it was a certified agency, qualified to administer its own projects, and the State transportation department role was minimal.

Level of Inspection and Testing

In response to questions asking for the relative levels of inspection and testing applied to different project types, generally higher levels of inspection and testing (i.e., daily testing or detailed field inspections) were applied to larger, more complex projects involving pavement or bridge rehabilitation, intersection improvements, or drainage structures. For smaller projects (i.e., scenic trails, or sidewalks), the levels of testing and inspection was somewhat reduced, but quite often, detailed field inspection was required for all project types, regardless of size or complexity.

Best Practices

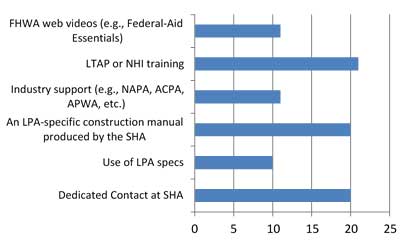

With regard to what tools help ensure QA is being performed properly, the LPAs highlighted training, industry support, having a dedicated contact at the State transportation department, and LPA specifications and/or construction manuals tailored to LPA projects (i.e., a streamlined version of the State transportation department’s construction manual). Figure 13 shows the responses.

NHI = National Highway Institute

NAPA = National Asphalt Pavement Association

ACPA = American Concrete Pavement Association

Figure 13. Bar Graph. Tools to assist LPAs with QA.

The surveys discussed previously were drafted with the intention that the survey responses would provide the research team with initial insight into the following areas:

Building on the survey results, the purpose of the interviews was to elicit information about several aspects of the dynamics between the LPAs and State transportation departments that were not readily apparent from the survey results from both the State transportation department and LPA perspectives in the States interviewed. In particular, the goals of the interviews were to (1) collect general programmatic information from State transportation department and LPA staff regarding program size, project types, and current QA practices, (2) obtain more insight into both program deficiencies and best practices that could be used to resolve these issues, and (3) gather and develop detailed case studies to support these findings if possible.

Follow-up face-to-face interviews and teleconferences were conducted with the following State transportation departments and LPAs:

Source: Sidney Scott

Figure 14. Photo. Blair Covered Bridge Historic Reconstruction, Town of Campton, NH.

The research team also attempted to schedule an interview with GDOT, but was not able to schedule interviews with the construction and local agency staff in time for the issuance of this report. The individual interview minutes, in appendix K, summarize challenges and best practices. The summaries below expand on the survey results and highlight the perspectives of both State transportation departments and LPAs from larger and smaller programs. The areas summarized below consist of general programmatic information concerning the agencies interviewed, oversight of QA for LPA projects, specific issues and weaknesses related to QA, and perceived best practices.

Programmatic Information

State Transportation Department Perspective: The interviews included State transportation departments with relatively large programs, a diverse number of LPAs, large and small, urban and rural, (California, Virginia, Florida, Washington, and Ohio), including counties, cities, and municipalities. The team also interviewed State transportation departments (New Hampshire, Maine, Wisconsin, Missouri, and Oregon) with smaller programs or with greater numbers of smaller, rural LPAs, and a State without a county system (New Hampshire). The larger State transportation department programs have the following characteristics:

The State transportation departments reported that even for the larger State programs, most LPA projects are less than $1 million and involve sidewalks, culverts, streetscapes, or small interchanges or bridge rehabilitation. Less frequently, LPAs have major projects, such as bridge or other signature projects, that require greater levels of funding, resources, and QA oversight.

For the State transportation departments with smaller programs or more rural LPAs, the State transportation department staffs typically are more directly involved in QA oversight for LPA projects, in some cases providing staff for periodic inspection, verification and acceptance testing, and IA. These State transportation departments typically require that LPAs essentially adhere to the same QA requirements as for State transportation department Federal-aid projects using the State transportation department standard specifications and QA manuals.

LPA Perspective: The local agencies interviewed included counties, cities, and towns. The LPAs ranged from small towns with minimal in-house staff that occasionally entered into a Federal-aid project as part of a Federal-aid improvement program (i.e., safety enhancement and accessibility, safe routes to school, urban construction, scenic trails, etc.) to large cities or county LPAs with significant capital construction programs, using LPA standard specifications, and employing in-house engineering and construction staff. For the purposes of this study, the smaller LPAs can be defined as those with smaller construction programs and minimal in-house staff, whereas larger LPAs have significant construction programs, and in-house construction and engineering staff capable of managing construction. Most of the LPAs, large and small, use consultants at some level to perform CEI services and QA testing on LPA projects. Several LPAs reported that the level of effort for construction management was the same regardless of the type of Federal-aid project. The consultants used were quite often former State transportation department employees with the same qualifications/certifications to perform the inspection and testing as for State transportation department projects.

Certification/Qualification of LPAs

Similar to the survey results discussed above, some ambiguity regarding certification/qualification programs was also evident during the interviews, revealing a need for further clarification and outreach on the possible benefits of such programs. The requirements for an LPA to become “certified” varied significantly among the State transportation departments interviewed. The interview discussions and a review of the previously collected literature suggest that a broad spectrum of certification/qualification processes are in use today, ranging from the LPA completing a simple self-assessment form or viewing training videos to the more rigorous, multistep interviews and partnering efforts to assign the LPA cradle-to-grave project responsibility. Because LPA certification/qualification is a key EDC initiative, an opportunity exists to standardize terminology and provide guidance on best practices related to LPA certification, particularly related to QA.

Issues and Challenges Related to QA

The interviewees, both State transportation department and LPA staff, were asked to comment on challenges or issues related to QA for LPA projects considering how often the issues arise and what the impacts might be. The interview forms included the issues that were generally identified in the FHWA and State transportation department process reviews. While acknowledging that issues were identified regarding insufficient QC testing and inspection being performed on LPA projects, both the State transportation departments and LPAs that were interviewed generally believed that there was a very low frequency of failing or noncompliant materials, and the greater challenge was with administrative paperwork and recordkeeping. Examples were missing test reports in the files, missing documents for closeout, and fewer tests taken or material certifications than required.

While the administrative paperwork issues related to QA on LPA projects generally did not result in significant or obvious direct quality impacts (i.e., failing materials, increased maintenance costs), it still could result in a significant cost or time impact or result in loss of Federal aid. One example, noted in figure 15 for a pedestrian bridge) resulted in additional costs to the State transportation department to hire a consultant to recertify the welds for the bridge, and a delay in closing out the project.

Figure 15. Photo. Keene Pedestrian Bridge, City of Keene, NH.

Other issues cited by the State transportation department interviewees included the following:

Most of those interviewed acknowledged that IA, whether performed by the State transportation department or the LPA, can be challenging. The State transportation departments with the least issues related to IA indicated that State transportation department staff retained full responsibility for IA testing. The interview discussions also revealed some confusion regarding the term “independent assurance” or IA testing. As used in the survey and interview questionnaire, the term was intended to refer to those activities performed to ensure qualified personnel are performing sampling and testing using proper procedures, and using properly functioning and calibrated equipment. Several interview participants initially responded to this subject thinking in terms of verification testing of contractor test results used in the acceptance decision.

A summary of LPA interviewee perspectives on challenges or issues related to QA for federally funded LPA projects included the following:

The LPAs generally agreed with the State transportation department interviewee perspective that the issues focused less on the quality of construction than the added administrative burden and cost related to complying with QA and other administrative paperwork requirements for Federal-aid LPA projects. The LPA perspective was different, however, in the sense that some LPAs felt that the additional QA-related soft costs, either for in-house staff, State transportation department, or consultant oversight, or for CEI, reduced the hard dollars allocated to construction and were not worth the additional investment. The LPAs generally did not offer quantifiable evidence to support their opinions regarding QA costs. It appeared that this perception of added burden and cost for Federal-aid also related to meeting other Federal requirements (i.e., Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO), Labor Compliance, Buy America). Some LPAs, particularly larger, well-capitalized local agencies with dedicated local funding sources, indicated that they do not use Federal funds on certain projects, particularly ones with complications, unless required or necessary.

Best Practices

Again, the interviewees, both State transportation department and LPA staff, were asked to comment on best practices to mitigate or address specific challenges related to QA for LPA projects. These best practices included the use of dedicated State transportation department staff for LPA projects, training for QA oversight, specifications tailored to LPA projects, use of consultants, standardized procedures for addressing deficiencies, checklists, and other practices.

One best practice consistently identified by State transportation departments and LPAs alike was regular face-to-face communication between State transportation department and LPA representatives. Several agencies, State transportation department and LPAs, pointed to greater or consistent use of project walkthroughs, and preconstruction or pre-paving meetings to define QA requirements, commitments and responsibilities, early action items, and milestones. It was also recommended that preconstruction meetings should be followed by periodic or quarterly coordination meetings to assess progress, raise issues, and develop solutions.

Training was also mentioned repeatedly as a best practice, but several representatives from both the State transportation departments and LPAs also noted that the high level of turnover at LPAs limits the effectiveness of periodic in-person training. One LPA suggested that the general training on LPA contract administration should be supplemented with more specific targeted training related to use of electronic systems and forms, and QA inspection and testing for specific project types or elements. Web-based training was suggested as an alternative or supplementary measure. The initial investment in online training could be costly but would save the cost of classroom training.

Most State transportation department interview respondents cited the development of specific LPA guidelines and manuals for administration of LPA projects as a best practice that has reduced the frequency of issues related to quality or noncompliance with QA. The initial analysis of these manuals, however, found that there were significant differences in the content and depth of the information, particularly related to construction administration and QA. The most effective manuals were those that included detailed guidance on construction QA and documentation requirements.

Several agencies noted that developing a risk-based or flexible approach to QA oversight based on the criticality of the project or the work or materials would provide a rational way to optimize State transportation department resources. VDOT is one agency that is currently attempting to refine and apply such a risk-based approach. One of the LPAs in Virginia, however, noted that applying different standards to different projects can create unnecessary complications in the field, with State transportation department inspectors often applying the same level of oversight to all projects.

The use of consultants was viewed as a best practice by some agencies but is controversial—not all the LPA respondents supported their use. A State transportation department implemented a relatively unique approach to the administration of LPA projects through its MC program. This program allowed the State transportation department to outsource the management of its LPA program by district without delegating its QA oversight responsibility. The State transportation department has independently evaluated the MC performance, and the findings were that program has been cost effective (compared with use of State transportation department staff) and has resulted in a much higher level of compliance with QA and other Federal requirements.

A large LPA commented that this MC oversight was not consistently applied, was frustrating—allowing no flexibility in requirements based on the project type—and created potential conflicts of interest with consultants working under CEI contracts for the LPA. Also the MC primary client relationship was with the State transportation department even though the LPA was partially paying for the MC services. A smaller LPA with fewer resources working under the same MC program commented that the MC program worked well and improved QA compliance and compliance with other Federal requirements.

Additional best practices suggested by both the State transportation department and LPA respondents included the following: