U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-15-008 Date: July 2016 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-15-008 Date: July 2016 |

This chapter aggregates all sources of information, including literature (i.e., process reviews, regulations and guidance documents, prior research, and PMIT database), and survey results and interviews from State transportation departments and LPA staff. It prioritizes the results in terms of key issues and challenges, and how perspectives on issues and impacts may differ based on the source (State transportation departments versus LPAs). It also evaluates best practices or practices that mitigate QA challenges from the different perspectives (FHWA, State transportation department, and LPA), considering compliance with 23 CFR 637, differences in State transportation department and LPA capabilities, and varying project types.

A review of the content of several (13) current FHWA/State transportation department S&O agreements was performed to assess the extent to which QA of the LPA program, construction oversight, and materials QA are being addressed in the overarching agreement between a given FHWA Division and its State transportation department. Specifically, the integration of the LPA-administered projects in the portions with materials QA and construction oversight was assessed, and each document was assigned a Rating (Good, Limited, Vague). The details of the evaluation done of each of the S&O agreements reviewed are presented in appendix I. Information that pertained to materials QA and construction oversight and the LPA program was only included in about one-third of the S&O agreements. In general, most of the S&O agreements were vague or limited in terms of information specific to local agencies and lacked emphasis on materials QA and construction oversight.

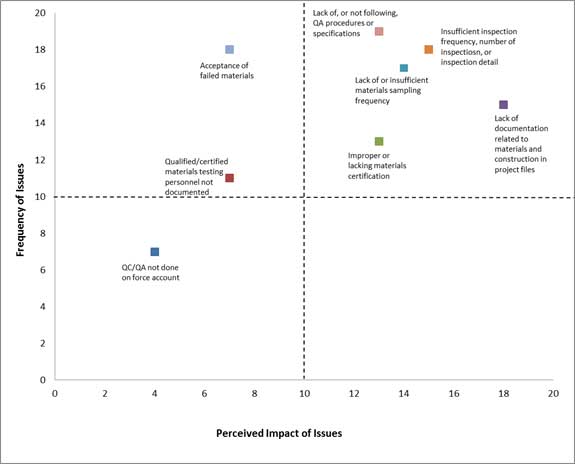

State transportation department survey respondents were asked to qualitatively rate issues or challenges based on how often they occurred and what the perceived impacts were. These results are combined in figure 16 to illustrate the key issues (in upper right quadrant of the scatter plot) that are of most concern to State transportation department staff. The identified challenges were initially derived from the FHWA or State transportation department process reviews and carried forward in the surveys and interviews.

Figure 16. Scatter Plot. Ratings of State transportation department issues.

This evaluation indicates that the issues of greatest concern to State transportation departments were 1) lack of or not following QA procedures or specifications, 2) insufficient sampling or inspection frequency, and 3) lack of QA documentation. These issues are understandably a primary concern based on the State transportation departments oversight and stewardship responsibilities to ensure that LPAs comply with the 23 CFR 637 requirements. It also should be noted that an equivalent number of State transportation department respondents reported that these issues had a relatively low frequency of occurrence and minor or minimal impacts.

During the interviews, some of the same issues identified by State transportation departments from the surveys were raised by the State transportation departments (i.e., lack of or not following QA procedures). Several other issues were also raised during the approximately 27 interviews held with State transportation department, FHWA Division, and LPA staff. These are summarized in table 6. The table prioritizes the additional issues based on the number of times reported. It also identifies the source of the responses (State transportation departments or LPA), and perceived level of importance ranging from minimal to significant.

Table 6. Additional issues raised during interviews.

| Other Issues Identified | Frequency | Raised by State Transportation Department | Raised by LPA | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of QA for LPA projects related to Federal-aid requirements for QA oversight, documentation, and electronic data management | 5 | No | Yes | Significant |

| Lack of communication among all project partners (FHWA, State transportation department, and LPA) | 5 | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| State transportation department or consultant inspectors adhering to State transportation department standards or unreasonably strict standards for all projects | 3 | No | Yes | Significant |

| Confusing contractual obligations regarding testing and QA for LPAs and contractors | 3 | Yes | Moderate | |

| Frequent staff turnover at LPAs (and State transportation departments) | 3 | Yes | Yes | Minimal |

| Compliance with IA challenging for smaller LPAs or not well understood | 2 | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Inconsistent QA oversight or inspection by State transportation department or its consultants | 2 | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Frequent updates of specifications or manuals for local agencies | 2 | No | Yes | Minimal |

| Poor testing equipment | 2 | Yes | No | Minimal |

The State transportation departments interviewed generally reported that improvements with LPA quality were realized more recently after the completion of the ARRA 2009 program.(24) State transportation department interviewees also commented that significant improvements in QA were realized when LPA-specific guidance manuals and specifications were implemented. More than 22 State transportation departments have developed and implemented LPA guidance manuals. The team’s content analysis, however, found that a smaller number of the manuals provided detailed guidance on QA procedures for construction.

Quite often the greatest “impact” on the LPA project perceived by both State transportation department and LPAs was the loss of Federal funding. Based on the general responses received from surveys and interviews, this impact was triggered by a lack of compliance with QA documentation requirements and procedures for Federal-aid LPA projects rather than by poor quality. Concerns expressed by State transportation department interview respondents noted in table 6 are discussed in more depth in the following paragraphs.

Lack of Communication

Lack of communication was identified as a reoccurring issue by both State transportation department and LPA respondents. Several State transportation department respondents indicated there was need for better, upfront communication of the project QA requirements particularly for LPA staff and/or consultant inspection staff at preconstruction meetings. This communication also needed to continue during the project, with periodic construction meetings attended by State transportation department and LPA staff. It appeared that this issue more often arose when State transportation department construction oversight staff were overextended (overseeing both State and LPA projects). Several State transportation departments reported that they had implemented preconstruction meetings in conjunction with periodic training to better communicate QA requirements to all, including State transportation department oversight staff.

Frequent Staff Turnover

State transportation departments cited staff turnover at LPAs as an issue related to knowledge of Federal-aid QA requirements. Some LPAs reported that they deliver Federal-aid projects infrequently, and do not retain the in-house experience. Smaller State transportation departments, however, indicated that they did not deal with this issue because they used qualified former State transportation department consultant staff with extensive knowledge of Federal-aid requirements. An LPA similarly commented that State transportation department staff turnover caused inconsistencies in how QA oversight was administered from one district to another.

Compliance With IA

Based on the State transportation department survey responses and as further clarified during interview discussions, complying with Federal IA requirements for LPA projects is recognized as a challenge, particularly for smaller local agencies where the State transportation department does not routinely perform IA for LPA projects. Also it appears that IA requirements were not consistently understood by all LPAs. One State transportation department reported that IA was not performed for LPA projects for many years, but it now performs IA for LPA projects and certifies consultant testing laboratories on a statewide basis, which has greatly improved compliance.

Certification of LPAs by State Transportation Departments

Although not an issue raised by the State transportation departments, there appeared to be some ambiguity regarding certification/qualification programs evident during the interviews, revealing a need for further clarification and outreach on the possible benefits of such programs. The requirements for an LPA to become “certified” varied significantly among the State transportation departments interviewed. The interview discussions and a review of the previously collected literature suggest that a broad spectrum of certification/qualification processes is in use today, ranging from the LPA completing a simple self-assessment form or viewing training videos to the more rigorous, multistep interviews and partnering efforts to assign the LPA cradle-to-grave project responsibility. Because LPA certification/qualification is a key EDC initiative, an opportunity exists to standardize terminology and provide guidance on best practices related to LPA certification, particularly related to QA.

Large Versus Small State Transportation Department Programs

The perceived issues depend on the size and complexity of the State transportation department programs. The larger State transportation departments with commensurately larger, more sophisticated LPA programs shift greater responsibility for administration and oversight of projects to the LPAs that achieve “certified acceptance” or “certified” status while still retaining overall responsibility for QA through periodic auditing and recertification programs. The larger State transportation departments focus on ensuring that “certified acceptance” LPAs meet the 23CFR 637 QA requirements. In conjunction with this, the larger agencies have, to varying degrees, developed a tiered approach to QA oversight, and may use less stringent LPA-specific specifications and guidance for noncritical projects. In contrast, the smaller State transportation departments, or State transportation departments without LPA certification programs, provide more direct QA oversight with State transportation departments staff, often using the same level oversight for different project types, and using State transportation departments standard specifications and QA requirements.

Cost of QA

The LPAs shared some of the same issues respondents noted in table 6, but the perception of issues differed markedly. For example, several of the LPA respondents reported that Federal-aid QA procedural documentation requirements for construction QA and closeout significantly increased costs, requiring additional internal resources and staff time, which reduced the direct dollars allocated to construction. This response was noted in both the survey and interview responses addressing the cost of QA in chapter 2 of this report. For example, in response to the survey question asking what percentage of project funds, one LPA noted in the survey results that the cost of QA for Federal-aid more than doubled (10 percent for locally funded versus 30 percent for Federal-aid projects). An LPA interviewee similarly reported that the cost of a Federal-aid portion of an ARRA project was approximately twice the cost of the locally funded portion. However, this QA cost issue was not raised by the majority of LPA respondents, and it was also noted that the additional costs on Federal-aid projects were in part caused by meeting other Federal-aid requirements (i.e., EEO, Labor Compliance, and Buy America).

While the surveys indicated that a greater level of State transportation department field inspection oversight was often applied to critical pavements and bridges, a significant number of State transportation department responses reported that the level of inspection by State transportation department or consultant staff (i.e., periodic detailed field inspections) was the same across all of the LPA project types. One LPA representative commented that the State transportation department used a “one size fits all” approach to QA oversight caused unnecessary expense, particularly on smaller, less complicated projects. Some of the larger LPAs (particularly the well-capitalized LPAs with dedicated local funding sources and in-house staff) also indicated that they would not use Federal funds on most of their projects, particularly ones with complications, unless required or absolutely necessary because of the additional cost and resources required.

Adherence to State Transportation Department Standards

Three LPA respondents commented that State transportation departments or their consultant representatives used unreasonably strict State transportation department standards for all Federal-aid projects. This perception, however, was not shared by all the LPAs, particularly smaller LPAs with fewer resources. The smaller LPAs shared the perspective of the State transportation department that for LPAs with few resources, the use of State transportation department or consultant resources for oversight and the use of standard State transportation department specifications worked well to ensure compliance with all Federal-aid requirements.

The combination of survey responses and anecdotal feedback from interviews regarding best practices were evaluated and characterized, and are summarized in table 7. In both surveys and interviews, the State transportation departments and LPAs were asked to identify each of their effective practices. Selected State transportation departments were further asked to assess the level of implementation effort as low, moderate, or high (e.g., amount of staff time required, number of staff required, and cost required). They were also asked to rank the practices in terms of the level of effectiveness as minor, moderate, or significant (e.g., significant effectiveness would result in a major reduction in frequency of occurrences, improved streamlining, and require less State transportation department staff time).

Table 7. Effective practices used for materials and construction QA.

| Best Practice Strategy | No. of Times Reported | Reported by State Transportation Department | Reported by LPA | Level of Implementation Effort | Effectiveness to Reduce Frequency or Impact of Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training (Total Reported = 31) | |||||

|

31 | Yes | Yes | High | Significant |

| LPA-Specific Guidance/Documents (Total Reported (31) | |||||

|

27 | Yes | Yes | High | Moderate |

|

4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Effective QA Management by State Transportation Department (Total Reported = 30) | |||||

|

16 | Yes | Yes | High | Moderate |

|

1 | No | Yes | ||

|

4 | Yes | Yes | ||

|

4 | No | Yes | ||

|

2 | Yes | Yes | ||

|

3 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Use of Consultants (Total Reported = 27) | |||||

|

24 | Yes | Yes | Moderate | Significant |

|

3 | Yes | No | ||

| Certification (Total Reported = 21) | |||||

|

17 | Yes | Yes | Moderate-High | Significant |

|

4 | No | Yes | ||

| Communication (Total Reported = 11) | |||||

|

4 | Yes | Yes | Low | Significant |

|

2 | Yes | Yes | ||

|

5 | Yes | No | ||

| QA for LPAs Same as for State Projects (Total Reported =8) | |||||

|

4 | Yes | Yes | High | Moderate (Small Programs) |

|

4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Buy Out Federal Funds With State Aid or Local Funds (Total Reported = 2) |

2 | No | Yes | Low | Moderate |

| Additional LPA funds Set Aside in Advance for QA Required on Federal-Aid Projects (Total Reported = 2) |

2 | Yes | No | High | Significant |

| Warranty Specifications (Total Reported = 1) | 1 | Yes | No | Moderate | Moderate |

The best practices were assessed in terms of their frequency of use, in conjunction with their perceived level of effectiveness and implementation effort, as reported by the State transportation departments and LPAs.

Communication

This category consisted of a number of reported communication practices that improved understanding and compliance with Federal-aid requirements. These include periodic stakeholder, partnering, or community of practice meetings with all the project players as recommended by FHWA through its EDC 2 program to improve understanding of FHWA Federal-aid requirements. Effective project-level practices included attending predesign walkthroughs and preconstruction meetings to define requirements and roles and responsibilities, and requiring the development of specific QA plans for LPA projects. As a whole, these strategies were perceived to require a relatively low level of effort to implement with a significant level of effectiveness.

Use of Consultants

One area of focus arising from the interviews was exploring use of consultants for either oversight or day-to-day management of the construction phase of federally funded LPA projects. The use of consultants was viewed as both an issue and a best practice with a moderate level of effort to implement. LPAs routinely use consultant staff for construction management of LPA projects. Some of the larger LPAs with in-house construction staff viewed the use of consultants as adding an additional unnecessary layer of cost to the project or reducing quality because the consultants were not adequately qualified or experienced to perform testing or inspection. Smaller LPAs believed that the use of consultants was an effective practice for LPAs that do not have the internal construction resources or need additional staff infrequently to deliver larger projects. Both challenges and benefits were reported by both State transportation departments and LPAs, and a summary of both is presented in table 8.

Table 8. Summary of challenges and benefits reported for use of consultants on LPA projects.

| Perceived Challenges |

|

| Benefits |

|

Based on the information presented by a number of State transportation departments, it appears that, on the whole, the use of consultants for the construction portion of LPA project development is necessary in many cases for smaller LPAs and can be an effective practice to comply with QA requirements if implemented with certain conditions. A key criterion is that the consultant staff used by LPAs must come from a State transportation department prequalified process in which the consulting firm’s capabilities and performance history is closely monitored.

An effective model to follow could be that of NHDOT, one of the smaller State transportation departments programs interviewed, where the consultants are trained and vetted by the State transportation department and then the list of consultants qualified for inspection and testing is given to the LPAs for use in the selection of consultants. An LPA with fewer resources (i.e., a town or rural county) generally relies on consultants for construction administration. When the State transportation department meets with the LPA at a preconstruction meeting, it establishes the requirements for the QA program, and expects the LPA to have under contract a testing agency certified for whatever work will be conducted (i.e., through the Northeast Transportation Training and Certification Program), and to provide a testing plan (e.g., soils compaction testing). The consultant under contract to the LPA must prepare the contract, plans, and specifications in a form as close as possible to the State transportation department’s specifications, or in accordance with the department’s LPA manual.

Consultants are also required to attend the NHDOT training at the same time as the LPA, once a project is awarded. The 2-day LPA training is done twice per year, and participants are issued a certificate that is good for 3 years. The State transportation department is starting to develop a recertification or refresher course; however, this course is more about the LPA process and project documentation. The State transportation department also offers a Construction School, which is a comprehensive training course also offered to consultants for 2 days to cover construction QA. As a result, the State transportation department observed a significant reduction in QA issues in the LPA projects. On the whole, the success of the program was attributed to establishing defined contacts at the State transportation department for LPAs, assigning each project a State transportation department project manager to perform QA oversight, and requiring the mandatory training for LPAs and their consultants. (An LPA cannot start the project unless its staff have come to mandatory training and become State transportation department certified.) The State transportation department estimated that withholding of Federal funds, attributable to materials QA or construction QA issues, occurs in less than 1 percent of the LPA projects.

A unique approach to the use of consultants in an oversight role was first piloted by WisDOT more than 15 years ago and implemented statewide in 2006 in response to severe State transportation department staffing shortages. WisDOT delegates direct project oversight on LPA projects to an MC in each of its region, who reports to a WisDOT Regional Project Manager. The MCs provide reviews and spot-checks for preliminary design, environmental documentation, final design, and construction management. FHWA essentially treats MC oversight as WisDOT oversight. A February 2012 evaluation of the effectiveness of the MC program over the 6-year history of its statewide implementation revealed that LPA compliance, including compliance with 23 CFR 637 QA Federal-aid requirements, has improved significantly since implementation of the MC program and has not been shown to appreciably increase costs. The MC costs were strictly compared with the cost of State transportation department staff performing the same suite of management services. Concerns raised regarding the use of MCs from the State transportation department perspective included the potential for conflicts of interest, loss of expertise and experience by WisDOT personnel, and limiting of career advancement opportunities for WisDOT personnel.

The LPA perspectives on the effectiveness of the MC program in Wisconsin were mixed. A larger county with in-house construction resources commented that MCs’ oversight was very rigid, using the same level of oversight for all project types, primarily served the interest of the State transportation department and not the LPAs that shared in the expense, and significantly increased the cost of QA oversight for Federal-aid compared with State-funded projects. A smaller county with limited in-house resources commented that the MC program in its region was very effective in helping the county manage its Federal-aid construction projects.

Based on feedback and ongoing discussions with its stakeholder groups, WisDOT is planning to continue with the MC program but improve its overall effectiveness, including developing a formal LPA certification program, developing standards more applicable to LPA projects, improving consistency in MC oversight among regions, hiring and training additional State transportation department staff, and conducting periodic stakeholder meetings.

Training

Based on the survey and interview responses, training was the most frequently cited best practice applying to both LPA staff and State transportation department staff providing oversight. As noted in process reviews, State transportation department district personnel and many LPAs were either not attending or were unaware of training available through their State on construction QA practices. For LPAs, the cost of training also can be an issue. LPAs cannot afford to attend training, particularly to become certified for materials testing, or do not have the right personnel to become trained. One suggestion was that the general training on LPA contract administration should be supplemented with more specific targeted training related to use of electronic systems and forms, and QA inspection and testing for specific project types or elements. Web-based training was suggested as an alternative or supplementary measure. The initial investment in online training could be costly but would save the cost of attending classroom training. Some State transportation departments currently offer LPA training to LPAs without charge, but long-term funding is needed to develop and maintain training programs for State transportation department, LPA, and consultant staff.

Certification Programs

There has been much documented discussion in past process reviews and reports on the topic of the certification or qualification of local agencies. The data from the State transportation department survey was reviewed critically to identify whether any trends existed in terms of fewer instances of issues with construction or materials quality observed in States with LPA certification programs. The results of this review found that certification and qualification programs are not being clearly defined by, or consistently applied by, the State transportation department. Some of the agencies require fairly rigorous qualification standards (interviews, pilots, shadow projects, recertification, partnering, etc.), whereas other State transportation department require that LPAs provide financial documentation (forms) and that LPAs and/or their consultants watch a training video such as the FHWA’s Federal-Aid Essentials for Local Public Agencies.

As an example of the more rigorous approach, WSDOT reported that 107 local agencies are designated as Certified Acceptance Agencies (39 counties, 63 cities, 4 port authorities, and Washington State Parks). The basis for eligibility is having appropriate and available LPA staff, along with a demonstration of satisfactory execution of federally funded projects through an “in training status.” Of the 107 local agencies, 104 jurisdictions have achieved LPA certification. In Washington, LPA certification assigns LPAs the full responsibility for project design and construction. While there are noncertified jurisdictions that receive Federal funds, their limited responsibilities in project execution are defined in agreements with the State transportation department. WSDOT regional staff members perform a final documentation review on every LPA project at the completion of construction to ensure that the LPA built the project in accordance with the approved design plans and contract.

If deficiencies or difficulties are found, WSDOT regional staff will conduct one-on-one training with the LPA. WSDOT headquarters staff conducts program management reviews to assess LPA’s compliance (rather than project-level compliance) and check that documentation is done appropriately. If an LPA is found to be out of compliance, then the agency is placed on a probationary status or its certification is revoked and more WSDOT oversight is assigned immediately. WSDOT indicated in the case study interviews that it will then take two or three successful projects completed by the particular LPA before they are reinstated to full delegation of authority.

The more rigorous approach, while requiring greater initial investment by the State transportation department and LPAs, appears to be an approach that will allow State transportation departments to delegate greater responsibility to qualified LPAs, reduce the level of State transportation department QA effort, while still meeting Federal-aid oversight requirements and empowering LPAs to take more responsibility for construction quality.

QA Management by State Transportation Departments

QA management by the State transportation department staff can be tailored based on the LPA type, size, or project risk/complexity. For larger “Certified” LPAs, State transportation department oversight may be limited to risk-based annual reviews or audits. For smaller or noncertified LPAs, State transportation department or their consultant staff may perform IA services, conduct periodic site visits/inspections, or provide full-time consultant inspection services and closeout QA reviews/audits. An additional effective practice included the use of checklists, a management practice cited in previous reviews. Overall, there were differences in the level to which management was applied by the State transportation department based on the frequency of inspections and on the number and types of LPA projects that are eligible for management by the State transportation department. Thus, the level of effort required by the State transportation department to provide QA services could range from low to relatively high. It would be beneficial for the State transportation departments to make these details clear in their LPA manuals and possibly they should be included in the content of the FHWA/State transportation department S&O agreements.

Regarding IA services, MaineDOT, a smaller program, uses two members of the State transportation department construction staff to perform all statewide IA, which includes LPA projects. MaineDOT also performs all asphalt laboratory testing for the LPAs, which was cited as a practice that reduces the number of instances in which the specifications are not being followed by contractors. Similarly, NHDOT assigns two or three IA staff, who comfortably handle IA on the number of LPA projects because their State has implemented system-based IA and QA. System-based IA allows the NHDOT greater flexibility to focus on individual LPA projects. NHDOT also has three QA consultants who are used on NHDOT project acceptance work but could be used on LPA projects. As a result of the IA management by the NHDOT, the sampling frequency is reduced for IA of LPA projects by taking into consideration smaller quantities.

In the case of larger programs such as WSDOT’s, regional offices are responsible for contract oversight on LPA projects. They perform detailed reviews on contracts, design plan reviews, and periodic inspection for noncertified agencies. However, because of the agency certification process, they are only required to carry out a cursory review of certified agency project contracts. This method allows WSDOT to delegate more responsibility to the certified agency to comply with disadvantaged business enterprise, contract language, QA, and other administrative activities for the construction phase.

Final inspection of LPA projects is done by WSDOT regional local projects engineering staff. WSDOT does not use consultants for conducting LPA project final inspections because the inspections are considered a compliance activity. The WSDOT local program office stated that deciding how detailed the inspection should be has to do with the performance history of the LPA completing the project. For example, certified agencies with good performance records may not require more than windshield inspection on low-risk projects because they have demonstrated high-quality work and compliance with design standards previously. This process also follows along the same lines as the shifting of additional delegation of risk to certified agencies because WSDOT does not perform a full review of agency design plans. Only a brief check is done to ensure compliance with FHWA requirements. However, project-level quality assurance is done by WSDOT primarily on accessibility projects and pavement jobs, or other work types that WSDOT has determined to be more high risk. For example, WSDOT performs detailed inspections on all accessibility projects to match grade requirements. State and regional WSDOT offices perform IA reviews to ensure compliance and identify systematic training needs.

LPA-Specific Guidance Manuals and Specifications

Based on a review of State transportation department literature, a majority of State transportation departments (39) have developed LPA guidance manuals, and in fewer cases have developed LPA-specific specifications or allow LPAs to use their own specifications. The development of these manuals can require a significant effort by internal State transportation department staff, but the interview responses from both State transportation departments and LPAs indicated that improvements in compliance with Federal-aid requirements have resulted from implementation of LPA-specific guidance manuals.

In recent years, States such as Ohio, Washington, and Florida have developed materials and construction specifications that are more tailored to LPA project elements. The motivation was to develop sampling and testing plans that are more suitable to the smaller scope and size of the majority of LPA projects. Each State has its own requirement in terms of when the LPA specifications can be used, but generally speaking, they are permitted on projects that are off the SHS.

For example, WSDOT, with participation from city and county representatives, has developed a standard specification for highway and municipal construction along with a lower-complexity LPA general specification. The generation of a separate specification for LPAs helps to streamline the design process for smaller, less complex Federal-aid projects that do not need to be held to more rigorous design standards. The version of the asphalt general specification that can be used for LPA projects can be viewed at the following Web address: http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/LocalPrograms/LAG/HMA.htm.

FDOT started transitioning its full specifications to streamlined LAP specifications for earthwork, asphalt, concrete, and landscaping in 2007.24 The LAP specifications are approved for use only on local roadways that are off the SHS. The asphalt and concrete specifications were compared to identify general differences between the full-blown State version and the abbreviated LPA version. The results of these comparisons are presented in table 9 and table 10. Generally speaking, the primary changes made to the materials specifications for LPA use include a modest reduction in the sampling frequency and quantity of samples, along with slight relaxation of the conditions (e.g., temperature or haul times) in which the samples or measurements are taken.

Table 9. Differences in specification requirements for asphalt concrete.

| FDOT Asphalt Specifications | FDOT LAP Asphalt Specifications |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 10. Differences in specification requirements for Portland cement concrete.

| FDOT Concrete Specifications | FDOT LAP Concrete Specifications |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Additional strategies reported included buyout of Federal funds with State aid, an LPA strategy to apparently avoid the additional effort/cost of compliance with Federal-aid requirements, and setting aside LPA funds in advance for Federal-aid projects, a difficult practice for most LPAs with limited resources and local funding sources.

Several State transportation departments responded that the use of the same QA practices as used for State projects was effective in assuring compliance. This approach, although considered effective for smaller State transportation department and LPA programs, was also viewed as a significant issue by larger LPAs, which resulted in unnecessary cost and effort, particularly for less critical project purposes.

The State transportation departments were asked in the survey whether they employ any practices that have been successfully applied to mitigate challenges with QA in LPA projects. A number of State transportation departments offered comments on the types of practices and to what extent these successful practices mitigate any challenges associated with materials and construction QA on LPA-administered projects. Information was also gathered via telephone and in-person interviews with the 10 focus States, and was combined with data from State transportation department and LPA surveys, addressing what solutions these agencies would suggest for improving issues or challenges that were reported.

Table 11 summarizes the key issues, sources by topic area, and proposed solutions. The key issues that were raised in the survey responses and the interviews were grouped into general categories and aligned with suggested best practice solutions offered by both State transportation department and LPA respondents. The categories are included only to simplify the alignment of issues with best practices. In some cases, there are multiple best practice solutions to a given issue or vice versa. The issues and proposed solutions also varied based on the source (i.e., State transportation department, large versus small LPAs). Lastly, the research team recommended the party or parties in the best position to manage suggested solutions.

Table 11. Summary of challenges and successful practices to mitigate challenges.

| Description of Key Issues/Challenges | Suggested Solutions | Recommended Party(s) to Manage Improvements |

|---|---|---|

| State Transportation Department/QA Management | ||

|

|

State transportation department headquarters with assistance of State transportation department district and materials staff and LPA stakeholder committee |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LPA/QA Management | ||

|

|

State transportation department headquarters with assistance of State transportation department district and materials staff and LPA stakeholder committee |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| State Transportation Department, LPA/Communication | ||

|

|

State transportation department headquarters, and LPA project team |

| LPA/Risk-Based Tiered QA Oversight | ||

|

|

FHWA Division and State transportation department |

| State Transportation Department/Training | ||

|

|

Funds could possibly come from FHWA to the LPA through Technology Transfer funds (LTAP) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LPA/Training | ||

|

|

State transportation department districts and/or State transportation department headquarters—Funds could possibly come to the State transportation department through Technology Transfer funds from FHWA |

|

|

State transportation department headquarters |

The evaluation of best practices solutions suggest that some solutions would be applicable to both State transportation departments and LPAs, whereas others would apply only to LPAs, either for larger or smaller programs. For example, both State transportation departments and LPAs indicated that training should be a required element of an LPA certification (and recertification) process for conducting Federal-aid projects. Also, both entities agree that the training should be parceled out in shorter segments (less than 1 hour in length) to keep each module concise, but also be in-depth and focused on specific elements of LPA administration, including construction QA. All of the State transportation departments agreed that training requires dedicated long-term funding with assistance from FHWA for funding, developing, and maintaining the training.

Some of the LPAs, particularly with larger programs, want to use a more risk-based approach (or tiered system), for construction QA tailored to the LPA project’s purpose. This suggestion was based on various observations by both State transportation departments and LPAs that there are instances of excessive amounts of QA testing required on small quantity projects. Part 23 CFR 637 would support a risk-based approach, particularly for verification testing or acceptance by certification or visual inspection for small quantities or noncritical materials so long as the State transportation department ensures that the essential QA requirements for Federal aid are met; however, it does not provide specific guidance on how to accomplish the shift to a risk-based system. In concert with a risk-based approach, the LPAs, particularly larger programs, would also like to see State transportation department QA requirements and standards tailored to LPA projects, primarily to reduce the amount of QA administrative paperwork.

The conclusions presented in this report were drawn from information provided through the following sources: existing literature on LPA programs, surveys of both State and local public transportation agencies, and in-depth interviews with both State and local public transportation agencies. The major deficiency identified and reported through this study, as in previous FHWA reviews, concerns the collection and retention of the appropriate QA and other administrative documentation for federally funded LPA projects. In spite of this deficiency, there were very few instances of poor materials quality or workmanship impacts anecdotally reported in this study. This leads to a conclusion that if the federally funded LPA projects are not experiencing poor workmanship and poor construction quality, then QA testing and supporting documentation can be tailored to fit the project type or purpose. The levels of construction QA testing and inspection can be adjusted accordingly based on the perceived level of risk or criticality of the project element.

The findings of this study also showed that smaller LPAs often lack the resources to perform construction QA and to consistently complete the QA documentation required on federally funded projects. At the same time, the larger LPAs reported that they have the training, staff qualifications, and capabilities to take on more of the QA role. Thus, it appears that a tiered system should be considered in which larger LPAs can achieve certification to take on a greater responsibility for QA, and smaller LPA projects can continue to be managed either by consultants (hired by either the State transportation department or the LPA) or by the State transportation department. There were reported benefits and challenges to both types of management strategies, and it would be up to an individual State transportation department to determine how best to address these challenges in their State.

Based on these conclusions, and on the recommendations offered by both State and local public transportation agencies, a number of recommendations can be offered for consideration. The recommendations for optimizing QA for LPA projects also address who would be the party responsible for managing the improvements.

Communication

Based on the findings of this study, the importance of communication and advanced planning cannot be stressed often enough. It is recommended that the State transportation department or its consultant representatives attend preconstruction and/or pre-paving meetings for all LPA projects. In Florida, construction feasibility reviews and predesign walkthroughs of the project to be constructed are performed by the State transportation department District Construction staff (including District Materials for critical or LPA projects on the SHS) and the LPA staff to identify issues early before design. The practice was reported to have beneficial impacts in providing immediate State transportation department construction and materials feedback prior to completion of the LPA’s design plans.

Direct and frequent communication during the project was considered a successful practice for mitigating issues with materials and construction QA, particularly when all parties (FHWA, State transportation department, and LPA) are periodically involved. The success of LPA projects in the construction phase was often attributed to frequent communication between the LPA staff and the State transportation department construction and IA staff. However, the communication should be strategic and clear and should extend beyond training.

The use of periodic statewide or regional stakeholder meetings or focus groups sponsored by the State transportation department, including periodic stakeholder partnering or community of practice meetings with all the project players, is a communication tool recommended by FHWA through its EDC 2 program to improve understanding of FHWA Federal-aid requirements. The meetings may include FHWA Division Offices, State transportation department, LPA, consultant and contractor representatives to discuss issues, share best practices, and improve construction QA.

The FHWA (primarily through the Division Offices with support from the Resource Center, Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center, and Headquarters) can work with the State transportation departments to establish mitigation plans on some periodic (e.g., every 2 to 3 years) basis. In adopting such a strategy, the opportunity exists to track how well the policies and practices related to the mitigation of materials and construction QA issues are working. It is also an opportunity to identify any new issues that have evolved and require the generation of new guidance, training, or tools for the State transportation departments and LPAs.

Consultants

A State transportation department that does not have adequate staff to cover the number of LPA projects active at any given time, should consider hiring MCs to help ensure that Federal-aid QA requirements are met for the QA activities related to the program. However, if a State transportation department elects to procure the help of MCs, it is critical that it maintain responsibility and oversight of the LPA program and use program reviews or audits at a specified frequency to ensure that there is consistent oversight and no conflict of interest between different levels of consultants involved in the overall LPA program. The emphasis on maintaining oversight comes directly from the 23 CFR 172.9(a) and 23 CFR 635.105, as well as FHWA Memo: Responsible Charge (08/04/11) in the sections related to conflict of interest.

For smaller LPAs that require the use of on-call consultants for construction inspection and testing, the State transportation department should establish a State transportation department based open ended (OE) consultant contract to be available to the small “one-project” LPAs. The OE consultant performs project management and QA. This process is suggested for projects costing under $1.0 million. These consultants should also be trained and certified to perform QA inspection and testing.

Where LPAs are required to use consultants to be eligible for receiving Federal funds for transportation projects, it is recommended that the State transportation department consider a tiered system. There were a number of State transportation departments that required that LPAs hire consultants on all federally funded projects, regardless of the project’s purpose, a practice that was increasing costs. Therefore, it may be beneficial for a State transportation department to establish criteria regarding which types of LPA projects it may require the use of consultants (e.g., a tiered level of effort) to allow smaller LPAs to use more of the available Federal funds on project components rather than project management.

LPA Guidelines and Manuals

State transportation department should develop and maintain LPA-specific guidance manuals or LPA project delivery manuals, which cover all of the LAP project types and include sections that specifically address QA in construction. A review of the existing manuals revealed extreme differences in the breadth and depth of information provided to assist the LPAs. Several State transportation departments focus primarily on preconstruction issues such as project selection, utility and railroad coordination, and ROW acquisition, with very little guidance on construction administration and QA. Several State transportation departments have made a considerable effort to provide guidance on how to perform materials testing and construction inspection and documenting the results (e.g., California, Washington, Maine, New Hampshire, Virginia, Georgia).

For example, one of these manuals includes a separate sampling and testing program guide for LPA-managed Federal-aid projects, requiring LPAs to develop a specific QAP for each project. The LPAs are required to define in their QAPs the quantity of each item in the project that requires sampling and testing, the number of acceptance tests required, an anticipated schedule for testing, the name and contact information for the party conducting the acceptance tests, and the sources of materials, including production plants for ready mix concrete, HMA, precast concrete, and structural steel. Frequency of sampling and testing tables are provided for soils, asphalt items, concrete items, and structural steel. For materials not included on these tables, the LPA may base acceptance on the producer’s certification that the material meets the appropriate State transportation department specification or inclusion of the material on the State transportation department QPL and submittal of a certificate of compliance.

This or similar guidance manuals can be used as examples for a State transportation department to develop or enhance its existing LPA manual with specific QA guidance. Finally, in conjunction with the guidance manuals, State transportation department should consider LPA manual online or in-class QA training for State transportation department (and LPA) staff, with “how to” PowerPoint tutorials on QA requirements.

LPA-Tailored State Transportation Department Specifications and Standards

Construction and design standards currently being required for use on federally funded LPA projects should be revisited to assess their applicability to the various types of LPA projects. The study findings revealed that the State transportation departments that generated LPA-specific materials and construction specifications that are more suitable to fit a particular LPA project purpose found it to be a worthwhile investment and had fewer instances of nonparticipation as a result. Furthermore, tailoring State transportation department specifications to be more relevant for local projects would eliminate the frustration reported by some LPAs regarding a one size fits all approach to State transportation department specifications for LPA projects.

Several State transportation departments have revised their materials specifications for certain qualifying projects on locally owned roads by reducing the testing frequency for smaller quantity jobs, extending the range of acceptable temperatures (+/-) for placement on site, and extending permissible delivery and transit times of materials, etc. One State transportation department indicated that it is considering creating simplified versions of the standard materials testing frequency tables for asphalt, structural concrete, and earthwork for LPA projects.

As an additional consideration, LPA bridges, box culverts, or other projects with construction values over $10.0 million are classified as “critical” in one State and held to the same materials testing and reporting standards as State roadway projects even if they are on the local road network. An issue raised by the LPAs in that State is that the “critical” portion (e.g., a bridge or culvert that is a component of a broader local roadway project) may only be a very small part of the overall project limits; however, the State standards would apply to the entire project and incur more cost. Thus, when critical elements constitute a small portion of a project, it would be more cost effective to implement an LPA-tailored specification and apply standard State QA requirements to only those critical elements.

Finally, several State transportation departments, particularly smaller more rural programs, stated that using the State transportation department standard specifications and QA procedures for their Federal-aid LPA projects was a best practice and has worked well to assure that LPAs comply with 23 CFR 637 QA requirements. While this practice simplifies the QA oversight of LPA projects for the State transportation department, it may not result in the optimal approach to meeting those QA requirements and may place a greater cost burden on the LPAs than necessary to achieve construction quality for less critical projects. Many of the LPA survey respondents indicated that QA costs can represent a significant percentage of project costs for Federal-aid projects. State transportation departments currently using this standard specification approach should consider piloting a project with LPA-tailored specifications that provide more flexibility in QA requirements and then assess the benefits to the State transportation department and the LPA.

Stewardship and Oversight Agreements

FHWA Division Offices should consider reassessing the current version of their S&O agreements to place more emphasis on the areas of materials QA and construction oversight, particularly as they relate to LPAs. It would be beneficial to provide the State transportation departments with a clearer vision of the expectations that FHWA has for the administration of the LPA program in the construction phase. The S&O agreements for States such as Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, and Ohio, give clear guidance on items such as responsibilities during construction and specific actions that cannot be delegated to LPAs, performance measures, and materials QAR review details. These documents can serve as starting point examples for FHWA to consider in future revisions of S&O agreements.

Certification Programs

One initiative that is being recommended through FHWA EDC 2 is to improve the Federal-aid projects administered by LPAs and mitigate the potential for noncompliance by encouraging State transportation department to develop certification or qualification-type programs.(4) These programs use criteria to ensure that the LPA is qualified to manage project activities that use Federal-aid funds. The FHWA-listed benefits of the certification program are in the areas of compliance, risk mitigation, resource reduction, and local ownership (allowing certified LPAs to manage and own their projects). Based on the findings of this study, a need exists for further clarity in defining what the criteria for LPA certification should be (particularly for QA) and for this information to be deployed consistently through national guidance from FHWA. The WSDOT certification program is a good model to consider as a starting point for wider adoption.

Smaller LPAs: Smaller LPAs reported that for the most part they prefer more involvement and guidance from the State transportation department. Thus, if the State transportation department has adequate, dedicated staff for the LPA program, the smaller LPAs would benefit from its involvement in QA, including performing testing and IA. For State transportation departments that do not have adequate staff to manage the construction phase of federally funded projects for the LPAs, it is recommended that consultants be used for oversight in a management role or for inspection and testing. The consultants should be trained and certified. The findings also suggested that the best approach to IA would be for the State transportation department manage it rather than assume responsibility for it. If the State transportation department will be performing the IA on an LPA project, it can be challenging to track ongoing testing to schedule the requisite IA activities. The LPA must take care to cooperate fully with the State transportation department’s IA personnel. For large projects, using the system approach to IA (in which IA frequency is based on covering all active testers and equipment over a period of time, independent of the number of tests completed on a particular project), can also be an effective strategy.

Larger LPAs: The larger LPAs consistently reported that they would prefer to have more autonomy and retain administrative control of QA and other costs in the construction of federally funded LPA projects. The implementation of an LPA certification program would allow larger agencies to take more responsibility for QA.

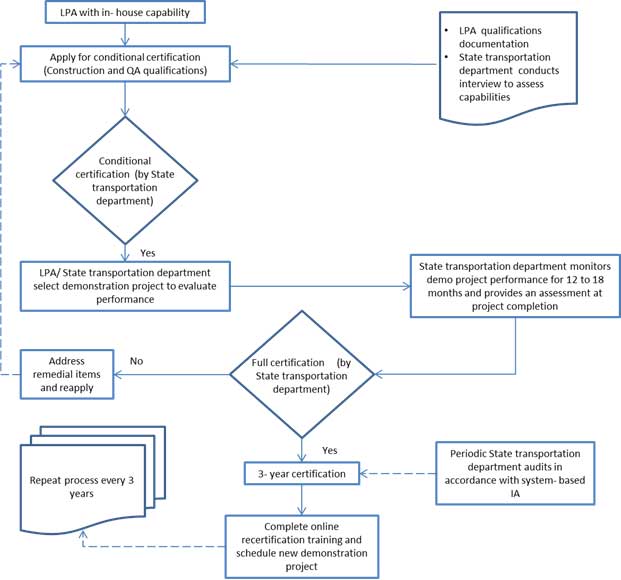

An example of a proposed two-step or tiered process for certification is illustrated in figure 17. As a first step, the LPA would submit its qualifications with the required documentation. The State transportation department would then conduct an interview with LPA staff to review past performance, current in-house staff, QA and construction inspection capabilities, and knowledge of Federal and State requirements. Given that the results of the interview are acceptable, the State transportation department would conditionally certify the LPA (e.g., Tier1). The State transportation department and LPA would then select an appropriate demonstration project for the LPA to administer on a trial basis.

Figure 17. Diagram. Process for tiered certification of an LPA.

It is recommended that the larger agencies seeking certification conduct a demonstration project prior to being permitted more independence with QA of construction and materials. This will give the State transportation department the opportunity to assess the LPA’s capabilities in performing quality oversight and the completing the appropriate QA documentation before approving the LPA for full (e.g., Tier 2) certification.

As noted in figure 17, the State transportation department should monitor the demonstration project for its duration (12 to 18 months are assumed). At completion, the State transportation department will assess the performance of the LPA and either approve the LPA for full certification or provide a list of remedial actions for the LPA to address to reapply for certification. With full LPA certification, the State transportation department would be required to conduct periodic audits and/or system-based IA as part of its stewardship responsibilities.

With a certification program where the LPA will have full responsibility for QA, it is recommended that a periodic recertification program be established to address potential staff turnover or training new staff. The recertification process should include mandatory periodic (e.g., every 3 years) training that the LPA engineering and/or public works staff should attend. It is also recommended that the recertification training be recorded in an online format (accessible online such as through an LTAP or a university’s distance learning) to address the scheduling challenges or travel restrictions often experienced by local staff. The State transportation department will still be encouraged to conduct its routine random audits on the large agencies that are certified and would ideally maintain a system-based IA program.

Recertification can also be tied to satisfactory performance (condition assessment) of the demonstration project over the 3-year full certification period. For example, WSDOT requires the tracking and reporting on the condition of local bridges and city arterial pavement conditions as part of the LPA project delivery, and it is part of the decision whether to certify (and to what level) an LPA.

Risk-Based Tiered System for LPA Projects

Based on the findings of this study, there appears to be a need to align the expectations of quality more closely with the LPA project’s purpose. The findings indicate that it may be beneficial for the FHWA to revisit how quality on federally funded LPA projects is currently being defined and to what level it should be documented. The materials sampling and testing activities for QA should be potentially structured as a risk-based (or tiered) system that considers the LPA project’s purpose and scope. The Washington, Florida, and Virginia State transportation departments have incorporated elements of a risk-based approach to QA oversight, and it is recommended that the approaches used by these agencies be investigated further for LPA projects to assess the advantages of allowing more flexibility without compromising quality. The risk-based (tiered) framework for materials QA acceptance that has been crafted by WSDOT is not intended for local projects in its current form; however, it would be a good starting point for guiding States on how to set up a similar process for the LPA program.(26) The options for establishing a risk-based system could be based on a project cost threshold or the criticality of the project or the element. For example, VDOT defines three levels of oversight (including QA) based on criticality of project elements as noted in appendix F.

For less critical projects, only random site visits or QA audits are applied in conjunction with delegation of approval authority and responsibilities within a State transportation department (i.e., in decentralized State transportation departments). For more critical projects or purposes, more frequent site inspections and/or testing would be required. It is clear that the move to a risk-based system should be calibrated to each particular State (i.e., what works for a small State-owned system such as in Delaware would not be suitable for a large county-owned system and a decentralized State transportation department such as in Texas). In addition, the move to a risk-based system would exhibit the most promise if tied simultaneously to the implementation of an electronic online project tracking and management system, similar to those currently used by Florida, Alabama, and Minnesota State transportation departments.

The establishment of a tiered system for LPA projects that move into the construction phase would allow delegation of responsibilities and approval authority to the State transportation department district level for decentralized State transportation departments, or to the maintenance districts for centralized State transportation departments, particularly for less critical projects for which the risks to QA are lower. This recommended delegation of certain responsibilities to the regional area would serve to streamline internal State transportation department approvals and reviews on LPA projects, as well as allow better tracking of LPA staff levels and capabilities. The implementation and maintenance of an integrated electronic tracking system for LPA projects would be a key to the success of moving toward delegation.

Training

The reporting of best practices and suggested solutions clearly indicated that the training of LPAs and their consultants had a high level of effectiveness in reducing the frequency of issues with QA. It is recommended that the training be parceled out in shorter segments (less than 1hour in length) to keep each module concise, but also be in-depth and focused on current challenges. The most effective way to do this would be to make some of the training segments Web-based, similar to the FHWA Federal Aid Essentials training series. It is recommended that there be dedicated long-term funding, along with the assistance of the FHWA for funding, development, and maintenance of the courses.

The FHWA Federal Aid Essentials training video on Construction QA was reviewed in its entirety, and the presentation of the content clearly explains the basic considerations involving incorporation of the different levels of QA in the construction of LPA projects. The discussion on QA programs outlines the roles and responsibilities for LPAs and encourages the LPAs to use the State transportation department’s QA program in their State. A distinction between the requirements for QA for LPA projects on and off the NHS was made. QA specifications routinely involved with LPA projects (contractor QC, agency QA acceptance criteria, and materials quality payment adjustment specifications) were also introduced broadly.

Based on the findings of this study, it is recommended that the FHWA consider developing additional videos within the topic area of QA, but to address the most frequently observed or most significantly affected topics uncovered as part of the review. These topics include system-based and project-based IA programs; estimation techniques for the cost of construction engineering, including the CEI and testing consultants; importance and impact of materials sampling frequency; daily construction records for LPA projects; construction dispute resolution for LPA projects; and managing materials testing subcontracts.

It may strengthen the learning content to include one or two example cases for each of the topics that show the problematic situation that occurred, the actions taken by the LPA, State transportation department, and/or FHWA, and the resolution to the situation (and perhaps also an explanation of how the project would have been conducted for QA to have been done correctly). A few examples of this type were provided by LPAs and State transportation department as part of this study.

Regulations

The development of a document similar to the FHWA Form 1273, as shown in appendix L, that assembles key Federal requirements for consulting engineering and construction contracts for use on LPA projects is recommended, prepared with feedback from stakeholders such as the American Public Works Association (APWA), American Council of Engineering Companies (ACEC), and the National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE).

As noted in FHWA’s procurement memorandum, procurement for projects not located within the highway ROW can follow State procedures rather than the Federal procurement process (49 CFR Part 18 2004). This flexibility applies to projects not within the highway ROW for most Federal-aid programs, including Transportation Enhancement Programs, Recreational Trail Programs, National Scenic Byways, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality, Off-System Bridges, etc., but excludes the Safe Routes to Schools Program and Nonmotorized Transportation Pilot Program. The memorandum explains that when an LPA is the contracting agency for a Federal-aid nonhighway construction contract, it is held to only State-approved procedures. This use of State laws and procedures also applies to the State agency’s awarding and administering of subgrants to local agencies. The flexibility exists for a State transportation department to advise LPAs to follow State procedures, local government procedures, or the procedures laid out in 49 CFR 18.36(b)–(i).(27)

Considering the feedback from State transportation departments and LPAs and the findings from this study, the FHWA and State transportation department Local Programs Office staff should consider that some flexibility exists in the 23 CFR 637 regulations for the development and execution of QA plans and in the administration of LPA projects based on project risk. Given this flexibility, State transportation department can delegate QA responsibility to properly certified LPAs but still must retain overall responsibility for adequate oversight of LPA project delivery as the primary sub-recipients of Federal funds. FHWA must also play a role by periodically reviewing and monitoring the State oversight. It is suggested that the FHWA form a small committee of practitioners from FHWA, State transportation departments, ACEC, NACE, and APWA to identify potential flexibility in the regulations and to reassess how they can be applied to optimize the QA requirements for LPA projects, based on the nature of the project type or purpose and risks.