U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| TECHNICAL REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-17-036 Date: March 2018 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-17-036 Date: March 2018 |

This chapter discusses key findings of the evaluation framed by the three evaluation questions described previously. The findings were shaped by the evaluation team’s literature and document review, participation in a program-sponsored peer exchange, stakeholder interviews, analysis of Eco-Logical approach steps completed by funding recipients, and qualitative coding analysis of stakeholder comments.

Evaluation Question 1: How has FHWA enabled State transportation departments and MPO stakeholders to adopt the Eco-Logical approach?

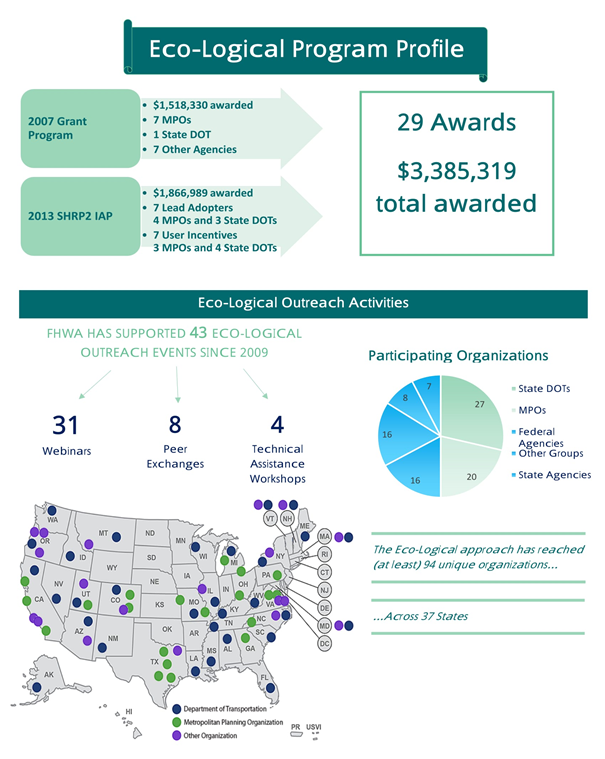

Some of the outputs of FHWA’s Eco-Logical Program include a resource document published in 2006 as well as multiple follow-on technical resources documents, 2 rounds of funding, 31 webinars, 8 peer exchanges, multiple case studies, and annual reports. (See references 3, 46, 4, 5, 11, 36–43, 47, 48, 12, 49, 13, 15, 18, 25, 34, and 45.) Outreach has engaged approximately 94 agencies across at least 37 States. Funding to recipients has totaled $3,385,319 for a total of 29 allocations made to 28 MPOs, State transportation departments, and other agencies (see figure 3).

The evaluation team’s review of past interviews of recipients and more recent interviews conducted in 2016 resulted in two key findings for evaluation question 1. Overall, the FHWA funding and knowledge/outreach events were effective in enabling stakeholders to adopt the Eco-Logical approach; however, it was not the primary driver for adoption in all cases.(35) In addition, FHWA funding helped agencies attract additional funding to support implementation of the Eco-Logical approach.

Source: FHWA.

Note: This graphic generated from a combination of published FHWA materials, and data referenced in the report adapted into a visual format.(50) Source information is described in greater detail in Section 3.1. (See references 3, 46, 4, 5, 11, 36–43, 47, 48, 12, 49, 13, 15, 18, 25, 34, and 45.)

Figure 3. Illustration. Eco-Logical Program profile.

Finding 1: FHWA funding allowed agencies to pursue previously planned activities sooner, more comprehensively, and with broader stakeholder buy-in.

In 2009, the 2007 Eco-Logical grant recipients were asked two related questions: (1) without the FHWA Eco-Logical Grant Program funding, would you have pursued the type of work you are currently doing? (all seven respondents answered “yes”) and (2) did the Eco-Logical Grant Program solicitation inspire you to attempt the Eco-Logical approach, or was this something your organization was considering or involved with prior to the grant? (all six respondents answered “no”). Respondents to the first question clarified their responses to explain that the work would not have been done to the same extent or with the same spirit without the FHWA funding. For the second question, respondents clarified that the grant broadened or expanded their scope and helped to get buy-in.

Early interview responses in 2009 indicated that recipients would have done their Eco-Logical work without the funding. This implies that the grant was not the primary driver for the work, although the funding did have an effect on it. One reason that all grant recipients might have already been performing Eco-Logical approach-type work could have been that the 2007 Eco-Logical Grant Program appealed to agencies that were already engaged in ecosystem-level planning. For the second round of funding through IAP in 2013, responses were not as consistent.

In 2016, the evaluation team asked the following questions to all funding recipients (both 2007 and 2013 recipients):

Of 19 responses, 12 agencies indicated that they would have completed their project anyway, 5 indicated that they would not have done the project without the funding, and 2 agencies indicated that they were unsure.

The 12 agencies that said they would have done the project anyway explained that they would not have completed the project so quickly or as thoroughly without funding. For the five agencies that responded no, their explanations included lack of time and resources to do the work without the help of the FHWA funding. Of those five agencies in the 2016 interviews, one of them was a 2007 recipient that originally responded differently when asked a similar question in 2009. One possible explanation for this discrepancy might be that different staff were interviewed in 2016 than originally in 2009. The other four agencies that said they would not have done the work without funding were 2013 funding recipients.

The following direct quotes, which describe how Eco-Logical funding supported agencies’ activities, are from funding recipients who were interviewed as a part of this evaluation in 2016:

“We were doing Eco-Logical before we received the grants…but what we were not doing, was integrating that information properly into the decisionmaking process.”[5]

“The grant has allowed us to increase our technical capacity, without [it] we would not have time or money to do this… the grant allowed us to look at it in more detail than we would have been able to do otherwise.”[6]

“[It had been our] goal to gather more info… to make decisions to be better environmental stewards; haven’t been able to do it due to lack of resources and other priorities; grant helped us to overcome these obstacles.”[7]

“This gave us the resources to branch out and acquire some of the tools and data, and to reach out to sponsor agencies such as FWS… If we didn’t have the grant, we would have done some environmental analysis but not to the extent that Eco-Logical enabled.”[8]

“But if we hadn’t had the funding we wouldn’t have gotten as far. We did have rudimentary maps that we would include in past MTPs [medium term plans] but this project really allowed us to advance the conservation objectives with the REF.”[9]

Some agencies commented that having their projects associated with a Federal program and with Federal research funding added legitimacy to their work. They also mentioned that other staff within the agency as well as other partner agencies could see the value in the Eco-Logical approach because of their projects.

The following quotes from 2007 and 2013 funding recipients describe the credence that the FHWA Eco-Logical Program offered agencies who sought to implement an ecosystem-based approach to infrastructure planning and environmental mitigation:

“[Our agency] was trying to do this, but were not quite there - one thing that was very helpful was having the Eco-Logical document as FHWA resource so [we] can create buy in from additional agencies – this has helped [us] to push the Eco-Logical approach.”[10]

“SHRP2 money made it feel important.”[11]

“The thing with grants is that it lends legitimacy to an idea or initiative—that’s what Eco-Logical grant did, and with the eight agencies adopting [the approach] that helped too.”[12]

“It was difficult to talk about grant to stakeholders since it was for a pilot level project, but since we said it was SHRP2 that gave us more credence since it was at the Federal level.”[13]

Finding 2: FHWA funding helped attract additional funding.

Although both 2007 and 2013 funding recipients were never specifically asked if the work performed under the FHWA Eco-Logical Program funding assisted them in attracting additional funding, eight recipients mentioned that this was the case. These agencies indicated that their Eco-Logical work positioned them to apply and be selected for additional funding opportunities, either to further their Eco-Logical work or due to their success with that grant or award. Additional funding sources that agencies mentioned included the National Association of Regional Councils, a local MPO, the Sustainable Communities Regional Planning Grant Program through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, and the U.S. Forest Service. (See references 51–54.)

Quotes from two of the recipients are as follows:

“[We] pulled together small amounts from other places, but Eco-Logical grant made the difference and helped attract other funding.”[14]

“Without the Eco-Logical plan, we wouldn’t have been positioned for HUD… So Eco-Logical allowed us to use the HUD funding to examine other important areas in our region and have a greater impact through planning.”[15]

It is a positive testimony to the Eco-Logical Program that several of the recipients built upon their Eco-Logical work and received additional funding from other sources or that their Eco-Logical work was received well and positioned them to be strong candidates for other funding programs.

Evaluation Question 2: How are State transportation departments and MPO stakeholders incorporating the Eco-Logical approach into their business practices?

The nine-step Eco-Logical approach can be applied in different ways and tailored to the needs of specific agencies and their partners. The evaluation team sought to understand how recipient agencies chose to apply the Eco-Logical approach and identify where they found benefits and challenges to implementation. The majority of interview responses focused on how agencies were implementing the Eco-Logical approach into their projects, so there was a wealth of data on how agencies were incorporating (or meeting challenges to incorporate) the approach into their business practices.

Findings 3 through 7 relate to this second evaluation question. Finding 3 indicates that most recipients followed the earlier steps (e.g., 1–4) of the Eco-Logical approach, which build the foundation of Eco-Logical and the focus on planning-level analysis. Findings 4 through 7 explore the successes and challenges that recipients faced in seeking to implement the Eco-Logical approach, summarized as follows:

The following subsections provide a more detailed look at findings 3 through 7 and their results.

Finding 3: 2007 Eco-Logical Grant Program recipients focused their efforts on completing steps 1–4 of the Eco-Logical approach, which are associated with collaboration, data sharing, and mapping and analysis of natural resources and transportation infrastructure.

The evaluation team analyzed published reports (see appendix A for a full list of reports) related to the Eco-Logical approach as well as notes from interviews of recipients to determine which Eco-Logical steps recipients completed or pursued (see appendix B). The evaluation team found that all recipients pursued step 1, and the majority of recipients pursued steps 2–4. However, relatively few recipients completed steps 5–9. Table 5 provides a summary of the number of recipients that completed each step. A detailed summary of the analysis of the nine Eco-Logical steps by recipient is provided in appendix H.

*Other recipients include a city transportation department, environmental non-profits, a State-level department of natural resources, a county-level soil and water conservation agency, and the USEPA.

The majority of the recipients who were classified as MPOs completed Eco-Logical steps 1–4, which focus on collaboration, data sharing, and mapping and analysis of natural resources and transportation infrastructure. These steps are more in line with an MPO’s role and responsibilities in planning than the later Eco-Logical steps. The MPO recipients did not complete steps 6–8, which are more applicable to State transportation departments and State-level agencies who are responsible for project design, construction, and mitigation of impacts.

All of the State transportation department recipients pursued steps 1 and 2. At least one State transportation department pursued each of the other Eco-Logical steps, as the responsibilities usually undertaken by State transportation departments include planning, project development, construction, and remediation. Four State transportation departments developed programmatic agreements.

The 2007 Eco-Logical Grant Program recipients included a range of other agencies, including a city transportation department, environmental non-profits, a State-level department of natural resources, a county-level soil and water conservation agency, and the USEPA. The grant projects undertaken by these recipients varied more than the projects undertaken by the MPO and State transportation department recipients. In addition, these agencies all have different roles and levels of authority in the transportation planning and environmental mitigation processes. All of the agencies in this category, however, completed steps 1 and 2, with the majority of agencies also completing steps 3 and 4.

Implementation of the steps is a long-term iterative process. While an agency’s completion of a particular step does not guarantee achievement of the step’s related outcome, incorporating steps into an agency’s business practices can contribute to better outcomes.

In summary, agencies may be pursuing the earlier steps of Eco-Logical based on the following two factors:

Finding 4: Recipients reported newly established or improved relationships with partners and stakeholders as a result of their Eco-Logical project.

Nearly all recipients (26 out of 28 total (93 percent)) reported that their relationships with external stakeholders and partners benefitted from their work on their Eco-Logical projects. In fact, some recipients reported strengthened relationships with partners among the main benefits of their Eco-Logical project (8 out of 28 total (29 percent)). The Eco-Logical projects provided recipients with specific reasons to reach out to partners and stakeholders and to work together in a way that they may not have in the past. Collaboration is the first step of the Eco-Logical approach, and sound relationships with partners are needed to make progress in the other steps. The quantifiable impacts of the Eco-Logical approach will take longer to evaluate, and so it makes sense that recipients reported relationships as a benefit of the Eco-Logical approach early on and throughout their projects. Through creating the REF or working on other aspects of the Eco-Logical approach, recipients reported strengthened or improved relationships with partners for a number of reasons, including the following four:

The following direct quotes highlight these themes, capturing what agencies reported over the years about their relationships with partners:

“…The product that we develop isn’t as important as the relationships you developed. There may be no major revelations from the grant itself, but now you’re more comfortable addressing issues with your new partners. I believe that there are ever-strengthening relationships between [our agency] and the resource agencies as a result of this project. It has helped us further the relationship with the resource agencies significantly here.”[16]

“…These three agencies established joint work plans in the early stages of the project. The work plans have been helpful in defining roles and establishing the framework for collaboration.”[17]

“…benefits thus far include much improved communication between agencies. The Eco-Logical work has been the impetus for further important collaboration, far beyond data delivery. Through continued and consistent communication, [the partner agencies] have found areas where we can partner and a have greater understanding of each other’s missions.”[18]

The Eco-Logical projects provided an avenue for recipients to reach out to partners and stakeholders in transportation and environmental planning. The collaboration can also yield success beyond the initial project. Four recipients noted that they were involved in additional projects with partners after the success of working together on Eco-Logical.

Although many recipients reported that relationships with partners improved through working on their Eco-Logical projects, they also reported on the challenges they faced when seeking to work with partners, as well as internal staffing issues. Finding 5 details the different aspects of these challenges.

Finding 5: Recipients faced challenges working with their partners due to different missions, goals, and responsibilities; varying levels of support for Eco-Logical activities from Federal agency staff at the headquarters and regional levels; and staff turnover.

While 26 out of 28 recipients (93 percent) reported on improved and strengthened relationships with external stakeholders, 23 recipients (82 percent) reported on the challenges they faced when working with their partners.

Most of the Eco-Logical Grant Program funding recipients were State transportation departments and MPOs, so they had to coordinate projects with each other; with local governments; and with local, State, and Federal resource agencies, among others. Each recipient involved in infrastructure planning and projects had its own interests, mission, and goals, and the political reality is that one recipient’s agenda did not always align with that of its partners.

The goal of Eco-Logical approach is to reduce the impacts of infrastructure projects and conserve or mitigate on a landscape scale. Recipients sometimes found challenges with getting local partners to consider impacts on a scale that extended beyond their jurisdiction. Recipients also reported challenges working with environmental and other resource agencies charged with issuing permits, as staff at these agencies do not typically focus on planning, on a larger scale or on a longer timeframe. The following quotes highlight challenges recipients faced working with their stakeholders, based on the different missions and responsibilities of all the organizations:

“…Local jurisdictions are very resistant to green concepts, mostly because jurisdictions are willing to trade some negative environmental impacts for the sake of growth. Our area saw some really bad recessions and are sensitive to economic challenges.”[19]

“The single largest challenge has been overcoming entrenched political opposition to transportation projects. We discovered that no amount of planning and outreach can overcome political obstacles, especially when dealing with multiple jurisdiction[s] with very different approaches and visions of transportation systems.”[20]

The Eco-Logical approach targets State transportation departments and MPOs, which are responsible for considering the impacts of projects on a State or regional level. State transportation departments and MPOs can influence what happens at the local level and encourage municipalities to think beyond their boundaries, but, ultimately, they cannot control what happens in on-the-ground implementation. This gap between the planning and project development and local level implementation is inherent to the transportation planning process in general. There are challenges that extend beyond the implementation of the Eco-Logical approach.

A total of 13 out of 28 recipients reported challenges with varying levels of support for their Eco-Logical activities from headquarters-level staff at FHWA and other signatory agencies, such as the USEPA and FWS, compared with division- or regional-level staff from those same agencies. Headquarters-level staff from FHWA and other signatory agencies strongly support the Eco-Logical approach, are knowledgeable of the approach, and want to promote it. However, some recipients reported that the support for the Eco-Logical approach did not always trickle down effectively to the division- or regional-level staff. Division- and regional-level staff are charged with many duties, and they may be more focused on legal requirements and the specific responsibilities of their jobs than supporting award projects. The following quotes illustrate these points:

“A disappointment with FHWA is that their comments are almost all about technical NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] side of things; [we’d] like to see more involvement on the bigger picture planning side. FHWA Division office seems more concerned with making sure this stands up in court rather than “real planning work.” Even the Division Planners are primarily involved in environmental document review.”[21]

“The high workload of [resource agency] staff also prevents the agency from working on the …programmatic agreement; [resource agency’s] participation in bi-weekly meetings with [State transportation department] has been limited; [State transportation department] is frustrated by the delays in working with [resource agency].”[22]

Additionally, some resource agencies may encourage a landscape-scale approach for conservation and mitigation but do not necessarily call it “Eco-Logical.” Such resource agency initiatives accomplish the same goals as the Eco-Logical approach but use different branding, which could affect awareness of similarities among programs.

In addition to the challenges working with external stakeholders described above, 12 out of 28 recipients (43 percent) reported that staff turnover posed a challenge to implementing the Eco-Logical approach. Some of the recipients reported that one person or just a few people at their agency implemented the award project. If that person or those people left, the knowledge and determination for implementing the approach would also leave. The following quotes illustrate these points:

“The success of the Eco-Logical process depends on the personality and mentality of the champion. Someone must really believe in it and dedicate themselves to its success. It cannot be mandated or rely on data alone.”[23]

“It has taken so much time and if I wasn’t doing this, there would be nobody else who would do it. How to institutionalize it- what if I left? How would the work continue?”[24]

“There was a lot of staff turnover at [multiple agencies] after Eco-Logical was completed; So people that were champions retired or moved on, and there wasn’t anyone that was sufficiently energized about this process to promote it.”[25]

Recipients noted that staff turnover, coupled with the issue that there is no legal or funding mandate for the Eco-Logical approach, can make it difficult for recipients and their partners to continue dedicating resources to updating the REF data and making progress in the Eco-Logical approach.

Nearly all of the recipients who reported experiencing benefits to relationships with external stakeholders also reported challenges when working with partners. Findings 4 and 5 highlight the complexities of relationships within and between different agencies but also the complexities inherent in the transportation and environmental planning processes. While recipients reported that a main benefit of the Eco-Logical approach is that it provides a process and framework for partners and stakeholders to work through together, the different missions and goals of agencies involved in the transportation planning process may include political realities that cannot automatically be resolved through the planning and collaboration that the Eco-Logical approach promotes.

Some recipients shared suggestions for their peers who want to overcome challenges described in finding 5, which is indicative of the motivation to achieve this aspect of the Eco-Logical approach. These suggestions include the following:

Finding 6: Although agencies faced challenges in data acquisition, sensitivity, and compatibility as well as in keeping data current, data sharing led to increased availability and use of data that were previously not accessible to other agencies.

Several recipients found it challenging and time consuming to get data from other agencies. Some agencies were hesitant to share sensitive material or data that were not already publicly available. One recipient shared that a partner agency was concerned about compromising data subjects (e.g., threatened or endangered species) if the location of a sensitive habitat could be located because of the scale of data being shared. It was a challenge to find a level of detail at which partner agencies felt comfortable sharing data that still provided sufficient detail to inform transportation planning. If transportation agencies could not acquire data in planning, they had to base early decisions on limited information that was not conducive to early mitigation and early consultation. Some recipients noted it was helpful to build understanding among the agencies on how each agency would benefit from sharing and how each agency would use the data.

Some recipients also faced challenges with data use and compatibility. Even within an agency, during the beginning stage of developing an REF, staff first needed to define the purpose of the data and how they would be used. This helped determine the kind of data the agency needed. For example, one recipient explained that understanding how the data would be used and by whom helped determine which data layers were necessary and at what level of detail. Compatibility between datasets also posed a challenge for some agencies both legally and technologically. For example, it was difficult to merge differently formatted State and regional data. It was also difficult to put data into a user-friendly format. This particularly applied to online tools where a user outside the agency would want to easily navigate and draw upon the dataset effectively in their own projects.

The most common challenge that recipients encountered with data (mentioned seven times) was keeping them current. Maintaining data costs time and money. Three recipients explained that they would only be able to update their data on an ongoing basis with additional funding and staffing. This implies that the data effort from their projects was possibly a one-time exercise. One recipient related that the region was experiencing a rise in development and, consequently, habitat loss. Unless the data were updated continuously, they would no longer reflect current environmental conditions with any accuracy. The following quotes illustrate this point:

“The ongoing challenge is to keep all data current. The new wildlife data will be difficult to maintain. In the future, [we] will need funding (and staffing) to keep data current unless [we] can develop a change detection process.”[26]

“On the data end, realized [we] will have a great data set, but if [we] look long term, [we] need to figure out a way to calculate the REAP [Regional Ecological Assessment Protocol] on the fly, so [we] don’t have to have a major calculation event every year.”[27]

“The time lag between the planning phase and implementation of NEPA document creates a challenge because data changes a lot in 20 years.”[28]

“Another challenge is to keep the data and application tool up to date so the tool and application can grow with this data. The project team tried to build in some mechanisms to update the data. With the pace of technology change, this might be a challenge.”[29]

Despite the challenges surrounding data, recipients reported several benefits of data sharing. Their Eco-Logical projects helped them acquire data that had not previously been available publicly and to layer it with other data for more comprehensive mapping tools and REFs. A couple of recipients created new online databases to share with the public and other agencies who might benefit from accessing and using the data.(55-57)

Data sharing allowed recipients and their partners to use data for more informed decisionmaking, as described in finding 7. One recipient reported that data sharing spawned communication between other partners for potential additional data sharing opportunities. Prior to the award to a State transportation department, a resource agency had been collecting data on highway culverts but had neither entered the data into a statewide database, nor had a system in place to share the data with the State transportation department. After the Eco-Logical collaboration, the two agencies were able to share data with one another. The following quotes illustrate this point:

“The methodology developed by [our agency] with its ranking system, data elements, etc. did a good job of putting weighed values on the ecosystem present in all the different areas of the region. This is the greatest value out of the Eco-Logical grant project. [Our] Eco-Logical ranking system used a raster system to get a greater level of detail, which made the product stronger than the approach previously used in the green infrastructure study.”[30]

“All this data is being put into Google Maps, so we’ll have a database that people can …click on the project and look at what the different types of impacts are. And based upon those impacts, we’re hoping to prioritize areas both on-site… and offsite, what are areas outside of the traditional transportation project where we want to look at mitigation.”[31]

“As far as we’re aware, this is the first time that there’s been a comprehensive regional view mapping project. In terms of taking all these different datasets and combining them, and making it available on our website and available to people…Conservation agencies will be able to use it for their own work.”[32]

Finding 7: The Eco-Logical approach led to improved integrated planning between environment, transportation, and land use. Additionally, many recipients have incorporated the Eco-Logical approach into their LRTPs and project prioritization processes.

The earlier and more integrated planning reported by recipients relates directly to the evaluation finding on external stakeholders. Working with a range of diverse stakeholders is an early step in the Eco-Logical process and is what led to greater integration between environmental, transportation, and land use planning. Many recipients found value in cross-disciplinary collaboration occurring early in planning through identifying shared goals, data, and plans. In some cases, that integration between disciplines did not happen previously. Oregon State University’s (OSU) Eco-Logical grant project is an example of integrated environmental and transportation planning.(58) As part of the project, the university worked with all three of Oregon’s MPOs to develop an integrated ecological and transportation plan, which grew into a large plan called Intertwine.(59)

Some recipients stated that their Eco-Logical work had informed their project prioritization process. One recipient explained that the Eco-Logical approach was being used as one of many performance measures, or lenses, that they could use to review and analyze a project. Project prioritization was affected in ways such as an MPO changing their evaluation criteria to include scoring for environmental considerations. One MPO recipient explained that it used the REF to analyze and review projects and to quantify potential environmental aspects. While recipients did not always directly attribute project prioritization to impacts, early identification of issues allowed for the avoidance and minimization of environmental impacts, which could improve environmental mitigation and yield time and cost savings later in project development (see findings 8 and 9 for more information on impacts).

Nine agencies explicitly mentioned that they used the Eco-Logical approach as part of their LRTP process. This means that the work done under the award helped them to integrate environmental considerations into their thinking about the future of their region. It also ensured continued earlier coordination since the Eco-Logical approach was being incorporated years in advance of actual project implementation. One recipient remarked that the strongest benefit of Eco-Logical approach had been the ability to adopt an action plan that raised the profile of environmental considerations in planning work earlier in the process. Additional quotes about the benefits of the Eco-Logical approach from recipients are as follows:

“[The award] brought the Eco-Logical approach to the forefront of [the] planning process; Eco-Logical principles are being directly incorporated into the MTP process.”[33]

“Eco-Logical has become a foundation for reviewing projects for the TIP, STIP and LRTP.”[34]

“The Eco-Logical approach has now been adopted by the policy board and is a part of the long range planning structure. It will provide for similar collaboration in the future. We have a real rationale to spend meaningful time on this now.”[35]

Despite these successes at the regional planning level, several MPO recipients remarked on their lack of authority when it came to ecosystem-level decisions made at the local project-level scale. This relates to finding 5 on the challenges in thinking beyond an agency’s jurisdictional boundaries and the handoff between planning and project implementation. Even if an MPO uses the Eco-Logical approach for region-wide planning, municipalities are not required to align their goals or use Eco-Logical data at the project level. Since regional planning agencies do not have the authority beyond planning, they depend on their local authorities to take on data, analyses, or decisions identified in planning and carry it into project implementation. One MPO recipient explained that its role is to pass along data and awareness but not to implement, and several other MPOs remarked on their lack of authority for land use planning. This dependence on municipalities and counties to take on the Eco-Logical approach for implementation is an inherent challenge related to the roles and jurisdictions of different agencies. The following quotes illustrate the challenges:

“Only other challenge is a lack of teeth that [our MPO] has for enforcement. In terms of implementing and trying to get jurisdictions to do these more progressive things, in [State], there is little ability for a regional planning commission to require those sorts of things. Ultimately you have to come back to education and outreach and push that as hard as you can.”[36]

“On moving from planning to implementation—our responsibilities are limited and [we] can’t do land use planning—need to rely on local partners to take on an implementation role and use the REF data in their decisions.”[37]

Evaluation Question 3: How have the Eco-Logical Program and approach contributed to improved project delivery processes and environmental mitigation?

The third evaluation question examines the planning process, project delivery, and environmental impacts reported by recipients while implementing their Eco-Logical projects. The Eco-Logical projects reviewed typically spanned 2–3 yr. Given the long time scale of transportation and infrastructure projects, the evaluation team found that, overall, there was little reporting on impacts (whether qualitative or quantitative time and cost savings) associated with the planning process and project delivery or improved environmental mitigation. Recipients were not required to track any cost, time, or environmental impacts as part of their Eco-Logical funding (although the SHRP2 IAP funding recipients used performance measures related to their projects), and the Eco-Logical funding did not necessarily provide resources to track these items. While few impacts were reported, some recipients did note that having examples of the time, cost, and environmental improvements that the Eco-Logical approach may afford would be useful in furthering adoption and implementation of the approach.

The evaluation team’s review of notes from past interviews with recipients for annual reports and more recent interviews conducted by the evaluation team in 2016 resulted in a few key findings for evaluation question 3. Overall, the evaluation team found that reporting on project delivery process improvements and environmental mitigation was limited and that of the agencies that did report any impacts, they were mostly qualitative in nature.

Finding 8: Recipients reported few comments on quantifying and tracking changes in project delivery processes and environmental mitigation as part of their projects.

The evaluation team coded 31 out of 767 comments (4 percent) as process impacts or environmental impacts. The process impacts category includes comments that indicate time or cost savings in the project delivery process, while the environmental impacts category includes comments that discuss avoiding or minimizing environmental impacts of development through integrated planning or comments that identify that agencies took steps to rectify, reduce, or compensate for environmental impacts if they could not be avoided.

The 31 environmental impacts and process impacts comments (29 benefits and 2 challenges) are attributed to 14 out of the 28 recipients. Table 6 shows the agencies that reported benefits and challenges in this area as categorized by the evaluation team. Overall, 8 comments are from 2007 Eco-Logical Grant Program recipients, 17 are from SHRP2 IAP lead adopters, and 6 are from the SHRP2 IAP user incentive recipients.

—Not applicable.

The Eco-Logical Grant Program recipients may have reported few overall comments related to process impacts and environmental impacts due to the following reasons:

Finding 9: Recipients reporting on project delivery and environmental mitigation impacts largely reported qualitative and anecdotal impacts, with some agencies noting that impacts were difficult to quantify and document.

For the 9 out of 28 agencies that reported environmental impacts, the comments generally dealt with the REF or similar GIS tool and the benefits that these tools provided for the agencies and their partners. This finding is consistent with the evaluation team’s inventory of the Eco-Logical steps, as it was found that the majority of agencies completed steps 1–4 of the Eco-Logical approach. Most agencies reported the following four qualitative benefits:

The evaluation team also identified two quantitative comments related to environmental mitigation. One MPO directly attributed the Eco-Logical approach to avoiding impacts at a planning level through projected preservation of greenfield lands, which improved environmental mitigation. Another MPO developed a decision-support tool to quantify environmental mitigation and encourage avoiding and minimizing impacts at a planning level. Comments are as follows:

“The land use strategies in the [regional transportation plan], which were informed by the work completed with Implementing Eco-Logical, is expected to avoid growth on 36 square miles of greenfield lands (23 percent savings from baseline)…The Implementing Eco-Logical work created the technical foundation for [our MPO] to develop its first Natural/Farm Lands Appendix to accompany the [plan].”[38]

“We introduced a new grant criterion that was derived from the ecosystem framework for all transportation projects from all funding sources; on the environmental side, [projects] get points for looking at the environmental map, and get points for doing avoidance, conserving, etc. We just finished scoring 100 projects, and …half embraced the criterion and are using it.”[39]

While most of the comments in this area discuss the environmental benefits associated with the Eco-Logical approach, a challenge was also noted that likely applies to other agencies. Although one agency was able to track the growth that was avoided on Greenfield land, other agencies may find the concept of avoidance difficult to track. Two of the 2013 recipients noted at the 2015 peer exchange that it was difficult to track environmental damage avoided by using the Eco-Logical approach because it was difficult to track what did not occur. The agencies’ representatives noted that they were not required to track what did not happen, and without additional funding or a mandate, this was not something that they have time to do.

For the nine agencies that reported process impacts, the comments generally dealt with how the Eco-Logical approach assisted them in improving the planning or project delivery process through activities such as centralizing data or encouraging stakeholders to communicate more often throughout the planning process. While most of the benefits are qualitative, some agencies noted that savings of staff time can be translated to cost savings in terms of reduced labor costs. The qualitative benefits reported by recipients include the following four:

Additionally, the evaluation team noted one quantitative process impact reported by a State transportation department as follows:

“With improvements made to the…website tool through the…User Incentive [award], users can now do a preliminary screen for sensitive resource or species areas in five minutes, where it would take the…environmental coordinator 30 days due to the volume of applications. If the preliminary screen does not result in any known concerns, the applicant has completed [state resource agency’s] review process.”[40]

The comment discusses the time savings achieved through using an online screening tool developed with SHRP2 IAP user incentive funding. The preliminary environmental resources screen can save up to 30 days in reviews per project as well as substantial labor time savings.

[5] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in March 2016.

[6] State transportation department employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in May 2016.

[7] State transportation department employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April 2016.

[8] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April 2016.

[9] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in March 2016.

[10] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[11] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[12] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April 2016.

[13] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April 2016.

[14] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in March 2016.

[15] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in March 2016.

[16] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[17] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[18] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[19] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[20] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[21] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[22] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[23] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[24] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[25] Other Organization Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in May 2016.

[26] Other Organization Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in May 2016.

[27] Other Organization Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in May 2016.

[28] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[29] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in March 2016.

[30] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in March 2016.

[31] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in March 2016.

[32] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April 2016.

[33] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April, 2016.

[34] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April, 2016.

[35] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[36] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[37] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April 2016.

[38] Eco-Logical Deployer; FHWA Eco-Logical Annual Report Team, phone interviews conducted 2008–2015.

[39] MPO Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April 2016.

[40] State Transportation Department Employee; phone interview conducted by evaluation team members Heather Hannon and Jessica Baas in April 2016.