U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-17-048 Date: May 2018 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-17-048 Date: May 2018 |

In the development of recommendations, the project team identified six categories of recommendations, referred to in this report as treatments. The treatments selected for the development of practice-ready recommendations are those that emerged from applying the working definition of complexity to each of the selected topics in development of the research activities. Each treatment, listed in table 81, is the result of understanding the interrelationships of various attributes within each research topic and the application of those relationships to practice outcomes, including those being evaluated in the field study and simulator study.

Each treatment is addressed using the format outlined in table 82.

The discussion of each treatment will describe the purpose and need of the treatment; present observed practices from chapter 5 of this report with sample case descriptions, as appropriate; discuss existing guidelines and research findings from chapters 2 and 5 of this report; and describe the specific treatment applications recommended for implementation.

Each recommendation is numbered according to the six topic areas and then assigned a sequential number within that topic area for ease in referencing the recommendations. Above the heading for each section in which a recommendation is described, applicable indexing symbols, matching those used throughout this report and introduced in chapter 1, are included to aid in quickly identifying the basis of the recommendation (see table 83).

Some recommendations in this report are justified on the basis of the consistency principle, when implementations of the TCDs were observed to be consistent within an agency, among locations, and with the general principles laid out in part 1 and part 2A of the MUTCD. While all the recommendations are considered valid on the basis of research conducted in this report or other literature, the consistency principle provides a means of identifying logical TCD applications and determining, in the absence of data and analysis of outcomes such as comprehension and driver performance, which applications are suitable for immediate implementation, field experimentation, or future research efforts. Practice-ready implementations explicitly validated by research should be considered suitable for inclusion in the MUTCD.

Treatment 1 covers the following topics:

In conducting the practices evaluation and literature review, the project team identified practices related to interchange configuration and geometric design that can lead to undesirable driver behaviors (e.g., sudden lane changes and reduced speed). The most notable undesirable practices are summarized in table 84.

While AASHTO’s Green Book addresses exit ramp placement, entrance ramp design, and other design criteria related to interchange design, agencies struggle to retrofit older interchanges.(16) In addition, agency practices for guide signing are often insufficient to address unique and complicated cases and, often, no mechanism exists to retain HFs professionals with experience in freeway sign design and TCD evaluation.

Research findings from the practice evaluation, field study, and simulator study identified practices related to ramp terminal design associated with the attributes in category 4200 and category 4300. Retrofitting existing interchanges to optimize the TCD implementations is a cost-effective means of improving the visibility of ramp terminals and providing explicit, specific guidance related to the navigation task.

Principles

Five basic principles of ramp terminal arrangements and design were identified in practice and policy:

The primary principle for ramp terminal arrangements is, concisely, to provide clarity for lane assignments and ample time for lane changes approaching interchanges. The anticipated outcome of implementing these principles is a reduction in crashes related to abrupt lane changes associated with uncertainty in the navigation task.

Application Examples

The following subsections provide examples of ramp terminal arrangements and design in two states: Washington State and Minnesota.

I-5 at SR 18 in Federal Way, WA

This interchange was reconstructed between 2010 and 2012. The project included the construction of direct-access flyover ramps connecting SR 18 to I-5 for the left-hand movements from SR 18. The entrances to I-5 northbound form two lanes, and the lane reductions occur immediately before an existing structure that was not included in the project scope. The acceleration lane for the eastbound to northbound movement is nearly 4,000 ft in length, despite the design speed of the flyover ramp being set at 40 mi/h. The benefits of increased acceleration lane distance include reduced driver workload, improved flow characteristics, and a more-resilient transportation system.

I-35W at TH 62 in Minneapolis, MN

When this interchange was reconstructed, separation of movements was accomplished with C/D roadways and the design of subsequent splits with distance for multiple overhead sign structures. For example, traffic on I-35W southbound bound for Lyndale Avenue S follows TH 62 westbound by using one of the two right-hand lanes. Further downstream, subsequent to the second split (for eastbound and westbound TH 62), overhead signs and “EXIT ONLY” pavement markings indicate to road users that the right lane is an exit-only lane for Lyndale Ave S. An appropriate sequence of signs with all primary destinations indicated, including on upstream signing, is particularly important in these applications.

Addressing ramp terminal design, ramp arrangements, and complexity caused by contributing attributes related to ramp terminals can be costly. On the other hand, even small changes to signing or ramp terminal characteristics can provide significant improvements in safety performance and traffic operations.

Recommendation 1-1: Provide Overhead Signing

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Where ramps occur in close succession, overhead signing and the use of lane assignment arrows (a white arrow on a green background) can address driver-expectancy issues and improve lane use, improving traffic flow characteristics.

Where escape lanes are present, that is, a short extension of the exiting lane along the mainline beyond the ramp terminal, provision of overhead signing consistent with geometric design can be problematic. Because of this, the use of escape lanes should be limited to locations where extremely short auxiliary lanes precede the ramp terminal. In these cases, clarity in overhead signing is extremely important and, while the signing may not match the geometric design, consistency in application will improve driver performance. The use of “EXIT ONLY” signing upstream of an escape lane, even for very short auxiliary lanes, has the potential to improve driver performance.

Recommendation 1-2: Construct Deceleration Lanes

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In cases where multiple, subsequent exits are closely spaced, the addition of deceleration lanes provides for the placement of overhead signing and marking. The placement of exit-direction signs in areas with deceleration lanes should be consistent with all other interchanges, such that the exit-direction sign is placed adjacent to the point of departure. Aids to the guidance task in a deceleration lane include dotted extension lines across the widening taper, dotted lane lines along the length of the full width of the lane, and a solid lane line in advance of the marked gore area to provide notice that the divergence is about to begin. In addition, vertical delineation can be provided in climates where snow-covered roads hinder the visibility of the pavement markings or reduced shoulder width makes the presence of the auxiliary lane difficult to discern from the width of the roadway adjacent to the through lane.

Recommendation 1-3: Ensure Clarity With Pavement Markings

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Implementing the consistency principle with pavement markings likely means using the lane drop marking or wide dotted lane line for all non-continuing lanes, even very short auxiliary lanes and lanes within cloverleaf interchanges. The broken lane line should, therefore, be used solely to separate lanes that continue on the primary marked route. In addition, lane addition tapers for non-continuing lanes (e.g., a deceleration lane) should be marked from the beginning of the taper to the full width using the dotted extension line. This prevents the large-width unmarked areas that can lead to confusion and cause erratic lane-change behaviors.

In addition, the clear marking of gore areas is especially important in areas where high-speed movements occur, particularly system interchange connections. Figure 72 illustrates the markings in a high-speed system interchange connection, where 24-inch-wide transverse lines, angled downstream on both sides of the single-direction divergence, are outlined by 8-inch-wide edgelines that are white in color until the physical nose of the gore area. RRPMs in crystal (white) outline the transverse markings and provide edgeline–appropriate spacing along the longitudinal lines.

Recommendation 1-4: Address Entering Lanes

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Some States, such as California and Michigan, have long-established practices of constructing auxiliary lanes wherever possible, even on freeway segments outside of urban areas. Comprehensive interchange type selection, interchange design, and geometric design criteria can provide a framework for selecting appropriate entering lane terminations that are differentiated with signing, marking, and geometric design features.

In particular, entering lanes that are auxiliary to the mainline lanes should be treated in a fashion similar to exit-only lanes that are the termination of a continuing lane. All entering lanes forming an auxiliary lane that is less than 1½ mi in length should be separated from the mainline lanes with a dotted lane line. For auxiliary lane lengths exceeding 1½ mi, the use of the broken lane line is appropriate, given that it is not considerably shorter than the portion of the lane marked with the dotted lane line, which itself will generally be at least ½ mi but typically 1 mi in length, to correspond to overhead signing.

Application of the consistency principle is particularly important in the implementation of signing for the entering lanes. Consistent placement of the W4-1 Merging Traffic sign will aid road users in determining the location of the lane addition. Vertical delineation alongside the inside edges of the mainline and entering roadway provide perceptive information related to the proximity of the marked gore area.

Each measure involves construction costs and costs associated with retrofitting existing interchanges. In cases where such retrofits reduce crash rates and reduce congestion, high benefit–cost ratios can be achieved.

Agencies exhibiting a high success rate with these implementations have established rigorous evaluation methods for system performance. These methods identify locations with upstream congestion that also exhibit higher crash rates. A systematic program of improvements with fast-tracked design and a dedicated funding source can improve the consistency of these implementations and provide immediate benefits.

All agencies can benefit from a regular program of pavement marking upgrades and the replacement of pavement markings in areas where markings are degraded because of high traffic volumes. A systematic evaluation of pavement markings in interchange areas and the implementation of a pavement marking standard that adheres to the consistency principle can lead to long-term reductions in maintenance costs and improvements in safety and operations.

Treatment 2 covers the following topics:

As part of the practices assessment, the project team discovered that State transportation departments and local agency implementations of sign panel layout and configuration principles often violated the consistency principle, were incongruous to the principles laid out in the SHS, and often sacrificed latent space on the panel that is considered helpful in grouping legends to aid in legibility and comprehension. The most notable undesirable practices are summarized in table 85.

The MUTCD depicts signing for interchanges throughout part 2 and generally separates information for separate movements onto separate sign panels. It does not contain information concerning the use of various separator lines (e.g., those extending to the edge border, those extending within a certain distance, and those with a length determined by the length of an associated text string).

MUTCD figures 2E-11 and 2E-12 show differing treatments of option lanes with regard to, where upstream, the option lane is depicted and how the mandatory movement lane is depicted. This inconsistency has led to State transportation departments adopting various methods of signing for these configurations and omitting the option lane from signing. Positive identification of all lanes available to a destination in a consistent manner is one potential technique for improving lane use in advance of interchanges with option lanes and reducing the likelihood of sudden lane changes.

The simulator study research tested different signing techniques for option lanes and the separation of signing into multiple panels, even upstream of a C/D roadway with and without exclusive downstream lanes for mandatory movements. That research found that separating panels for exits with downstream, high-speed splits resulted in greater subject confidence in upstream lane selection. In addition, it found no significant difference between signing methods for option lanes, and the participant questionnaire found an association between a new type of arrow for blended arrow option lane signing and comprehension of the purpose of the sign. All signs in the simulator study were designed with appropriate legend grouping, spacing, and legend size and composition.

Principles

The following principles should be followed:

Based on the practice evaluation and literature review, the project team proposes the following practice recommendations to address issues related to sign panel layout and configuration. The intent of these recommendations is to use sign panel arrangements to best convey the proximity of exits and their relationships to one another and to ensure that cues related to exit direction, ramp configuration, and the location of the physical gore are all incorporated into the sign design process.

Recommendation 2-1: Provide Separate Panels for Separate Movements

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A key component of guide sign messaging is the use of borders and separate panels to convey to motorists, through those cues, the relative arrangement of exit ramps and continuing lanes on a freeway segment. As part of the practice evaluation, the project team evaluated signing in urban areas in several States to examine locations where single sign panels were used to convey messages for diverging lanes.

Recommendation 2-2: Place Control Cities in Designated Order

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Few agencies address this specifically in their design documents. The placement of control cities, placement of arrows, and other sign legends should follow the “straight–left–right” principle for vertical arrangements and the “left-straight-right” principle for horizontal arrangements. For control cities, those to the left should be listed first and those to the right should be listed second. This is addressed in the simulator study, using the legend listing principles but applying them to a cloverleaf-style interchange, where the first movement is listed second on the sign because it is the right-hand movement.

Recommendation 2-3: Properly Align Exit Numeral Plaques

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Several States continue to center-align exit numbers, some with full-width exit numeral plaques. The alignment of the exit numeral plaques and the straightforward design of the “LEFT” legend within the plaque can contribute to driver understanding of left and right exits.

The sign in figure 73 plaque demonstrates single-line application of the “LEFT” and “EXIT” with number legend layout as compared with what is presently in the MUTCD. The sign depicted on the left facilitates left-to-right reading of the exit number and has the benefit of reduced overall sign height. In addition, by using the “LEFT” inset panel on both the exit number plaque and the primary guide sign itself, additional emphasis is facilitated by means of duplication of identical elements.

Source: FHWA.

A. Single-line LEFT exit tab.

Source: Adapted from MUTCD Figure 2E-15.

B. Multi-line LEFT exit tab.

Figure 73. Graphics. Advance guide sign for left exit with “LEFT” inset panels.

Recommendation 2-4: Provide Revisions to the MUTCD on Legend Sizes

![]()

![]()

![]()

The current structure of the MUTCD groups legend sizes into categories based on the roadway cross section and roadway classification (e.g., MUTCD table 2B-1) and type of interchange (e.g., MUTCD table 2E-4). These categories, however, do not take into account the roadway design speed, mounting of signs on both sides of the roadway, or the roadway cross section beyond two lanes. In not explicitly addressing sign sizes based on the factors that influence legibility distance, the tables in the MUTCD do not provide explicit information to practitioners for use in designing signs that fall outside of what is accommodated in the tables.

In practice, signing on conventional roads, including primary highways, often fails to provide legends of sufficient size for the design speed. In addition, in urban areas, placement of regulatory and warning signs on both sides of the roadway improves visibility for road users and sign sizes can often be reduced. One potential solution to the right-sized selection of sign sizes and legend elements is the use of a two-step process for selecting legend sizes. The first step is to use the posted speed limit (or 85th-percentile speed) in conjunction with the cross section to determine the size class that will meet those requirements. A sample size-class table, currently blank pending future research, is included as figure 74.

Once a size class has been determined by selecting the size from the appropriate intersecting row and column in the size class selection table, that size class is carried over to the legend and element size table (see figure 75). By reading down the column for the appropriate size class, the practitioner can readily determine legend sizes for various elements of signs for all size classes.

The use of size classes and one single table for guide sign design (and, as it is developed, regulatory and warning sign size selection) will aid agencies in uniformly applying sign design principles on low-speed roadways and high-speed, multilane, limited-access highways.

Recommendation 2-5: Clarify Requirements for Larger Initial Capital Letters

![]()

![]()

![]()

While cardinal directions should include larger initial capital letters, the use of larger initial capitals for action messages and legends (e.g., “TO” and “BYPASS”) has also been observed. The MUTCD should explicitly clarify that the legend height is uniform for these words to improve consistency in practice.

Recommendation 2-6: Include Option Lane Signing Conforming to Consistency Principle in MUTCD

![]()

![]()

![]()

The participant questionnaire from the simulator study included questions about various advance guide signs for option lanes. While all signs were found to perform consistently in the simulator, the participant questionnaire revealed that subjects reported a better understanding of the sign design used in alternatives C1 and C2 as compared to the sign design from alternative C4.

Statistical analysis on question 3-4 revealed that 67 percent of respondents indicated that the sign design from alternative C2 “provides clearer direction” to the destinations than the sign design in alternative C4.

The advance guide sign in figure 76, using the method from alternative C2 of the simulator study, indicates the downstream configuration of the lanes addressed by the sign. The left lane and right lane both serve the destination via exit 301, as indicated by the arrowheads. Unlike the conventional practice of using down arrows over the lanes, which was also found to be suitable for option lane signing in the simulator study, the null-terminated two-headed arrow method provides the benefit of indicating that the lanes continue straight before exiting. In addition, the null-terminated two-headed arrow, in lacking an arrowhead pointing up, has the potential to avoid confusion of the blended arrow signing of alternative C4, where arrowheads point right and straight into the same legend, the legend pertaining to the destination served by the exit.

Figure 76. Graphics. Option lane signing using the discrete arrow method with a null-terminated two-headed arrow in place of down arrow over option lane.

The design of the null-terminated two-headed arrow was inspired by similar designs on guide signs for roundabouts, where the circulating lane is terminated without an arrow, because no information about the destination of the circulating lane is provided on the guide sign.

Implementation costs vary for different groups of signing changes. MnDOT conducted a statewide sign modification in the mid-2000s to move all center-aligned exit plaques to the side of the sign corresponding with the exiting movement. The provision of separate signs for separate movements is difficult to estimate, as costs for structures can vary widely case-by-case, depending on the existing structure type, while the calculation of costs for fabrication and installation of sign panels (assuming a typical size of 12 ft 6 inches by 15 ft 0 inches) is relatively straightforward.

Treatment 3 covers the following topics:

In conducting the practices evaluation and literature review, the project team identified practices related to sign panel legend selection and placement of the signs themselves that can contribute to driver-expectancy violations. Some of these are related to existing policy, and others are violations of existing practice literature likely borne of designer inexperience and insufficient familiarity with HFs guidelines. The notable undesirable practices are summarized in table 86.

In cases where geometric design and other factors influence the placement of signs, designers often make choices that do not consider the overall use of sign panel separation, arrows, and other cues.

In figure 77, the overcrossing roadway obscures the view of the exit-direction sign in the gore area, while the upstream location of another sign is too far in advance for placement of an exit-direction sign. The design of the first sign does not include a distance, reference to the auxiliary lane, or an arrow consistent with this application. The second sign indicates dual exit-only lanes, which is not the case in this interchange, where only one lane is mandatory movement and the second lane is an auxiliary lane. No specific language in the MUTCD addresses these types of cases.

The simulator study found that regardless of signing alternative used, participants were generally able to successfully navigate complex interchanges as long as good signing practices and consistent implementations were followed.

Based on the practice evaluation and literature review, the project team is proposing the following practice recommendations to address issues related to the interaction of sign placement locations and the arrows and distance information displayed on sign panels. The intent of these recommendations is to use sign panel legends and placement of signs to best convey the proximity of exits and their relationships to one another and to ensure cues related to exit direction, ramp configuration, and the location of the physical gore.

Recommendation 3-1: Provide Distances to the Departure Point on All Primary Guide Signing

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Numerous States, particularly those implementing large APL signs, omit advance distances on some guide signs, especially exit-only and diagrammatic signs, where distances are especially important. Addressed in part 5, this is an issue of compliance with the MUTCD and is related to agency perceptions on the excessive size of the blended arrow signing.

Recommendation 3-2: Use Arrows Appropriate for the Sign Location and Geometry

![]()

Addressing the use of downward-pointing and upward-pointing arrows is essential to ensuring that arrows use can be applied consistently in practice. In addition, application of the consistency principle indicates that the use of upward-pointing arrows should be restricted to only those locations where geometric design includes an exit ramp or angled departure from the lane and should not be used in conjunction with lane changes.

In figure 78, access to the general-purpose lanes of a freeway is provided from the managed lanes by an exiting maneuver that involves a tapered lane addition. On the sign, the angled-up arrow is placed roughly in alignment with the beginning of the exiting movement taper; this use is consistent with using angled-up arrows for departing movements only, as the downstream double-white line provides a legal separation similar to a median or barrier. To the driver, this looks similar to a conventional exit, and the driver’s maneuver into the lane formed by the taper is unimpeded by any adjacent traffic. The use of the angled type A arrow is appropriate here, then, because the setting matches many other settings where angled type A arrows are applied.

Source: FHWA.

Figure 78. Photo. Use of a tapered lane addition to enter the general-purpose lanes of a freeway from the managed lanes.

In contrast, the configuration of the freeway in figure 79 does not include the addition of a lane or an exit-type maneuver. Rather, the access point for the general-purpose lanes is parallel lanes and lane changes, not an exiting maneuver, and motorists are required to access the general-purpose lanes from the managed lane. An angled-up arrow, typically reserved for geometry with an exiting movement, is used to indicate a lane-change movement far ahead of the break in the double-white lines, which prohibit these movements. The use of the angled type A arrow in this case is misleading, because road users who previously saw its use associated with a non-lane-change maneuver may make errant maneuvers, particularly in inclement weather where pavement markings are obscured. This broadening application of the angled type A arrow is incongruous with the consistency principle and violates road-user expectancy of the specific meaning of the arrow; namely, that there is an exit available proximate to the exit-direction sign.

Source: FHWA.

Figure 79. Photo. Use of misleading signing and parallel lanes and lane changes to access the general-purpose lanes of a freeway from the managed lanes.

The use of down arrows should be similarly restricted to those locations where there is not an immediate exit from the lane to which the down arrow applies. In Colorado, for example, down arrows are used on “EXIT ONLY” panels in advance of the exit and also at the departure point. When distances are omitted, this practice leads to broadening use of the down arrow, such that it is no longer restricted to upstream locations where a continuing lane is present, whether or not that lane is marked as “EXIT ONLY.”

Table 87 provides recommendations on the use of arrows such that use of arrow type and orientation is consistent with geometric design and accommodates legend grouping.

Recommendation 3-3: Provide One Arrow Shaft Over Each Lane

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The MUTCD specifically prohibits the use of multiple arrows pointing into one lane or associated with a single lane. Continuing instances of this practice can be addressed with information on the use of various traffic signing arrows.

Recommendation 3-4: Accommodate Angled Down Arrows

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Additional MUTCD language prohibits the use of angled down arrows. This research observed numerous instances where angled down arrows are used to effectively convey a change in alignment of the primary route or exiting movement for a high-speed movement. Specific language on the use of angled down arrows will limit their use in this way while explicitly prohibiting the use of more than one arrow over a single lane.

Recommendation 3-5: Place Exit-Direction Signs Adjacent to the Departure Point

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Addressed in chapter 5 of this report, the placement of exit-direction signs is critical information to the guidance task. MUTCD figures should be revised so that exit-direction sign placement is consistently illustrated as being adjacent to the point of departure, near the gore area. When this placement cannot be provided, the use of a 45-degree type C arrow should be considered for any exit-direction sign placed in advance of the point of departure.

The implementation of these measures is not expected to considerably increase the cost of signing for interchanges. Marginal height increases (18 to 24 inches) on some signs will be offset by significant reductions in sign heights because of the altered arrow designs of recommendation 2-6, even as continued use of the down arrows on the conventional practice is made.

Treatment 4 covers the following topics:

In conducting the practices evaluation and literature review, the project team identified practices related to delineation that can contribute to driver-expectancy violations. Many agencies neglect to use dotted lane lines (in lieu of broken lane lines) in advance of mandatory exiting movements. Other agencies do not differentiate between the dotted lane line and the dotted extension line, either in width or pattern, leading to confusion concerning the presence of a full-width lane and the applicability of that lane. The most notable undesirable practices are summarized in table 88.

Few States require the use of dotted extension lines along the lane addition tapers leading into restricted use or mandatory movement lanes. In Illinois and Virginia, dotted extension markings are used in lane addition tapers for left turn and right turn lanes on arterial routes. In North Carolina, dotted extension lines are used for all lane addition and lane-reduction tapers.

States typically avoid the use of dotted extension markings along the lane addition tapers where a continuing general-purpose lane is being added because motorist movement into that lane is typically not discouraged. In figure 80, the lane addition taper (marked with a broken red line) is not delineated with dotted extension lines, leading to veering behavior by westbound motorists leaving the tunnel and approaching the apex of the short crest vertical curve.

Source: FHWA.

Figure 80. Photo. The use of a lane addition taper (marked with a broken red line) not delineated with dotted extension lines.

The simulator study used dotted lane lines along all exit-only lanes. For clarity and to avoid additional effects, no word or symbol markings are used.

Based on the practice evaluation and literature review, the project team proposes the following practice recommendations to address issues related to the interaction of sign placement locations and the arrows and distance information displayed on sign panels. The intent of these recommendations is to use sign panel legends and placement of signs to best convey the proximity of exits and their relationships to one another and to ensure cues related to exit direction, ramp configuration, and the location of the physical gore.

Recommendation 4-1: Provide Differentiated Markings

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Differentiated markings should be provided for continuing lanes, mandatory movement lanes, and areas of transition (lane-reduction tapers and lane addition tapers for exit-only lanes). For full-width lane areas, solid, broken, or dotted lane lines are used. For transition areas (lane addition and lane-reduction tapers), the dotted extension line provides a visual cue about the taper while also providing a boundary for vehicles intending to remain in the adjacent lane.

Recommendation 4-2: Provide Lane Use Arrows for All Exiting Lanes

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Several States provide lane use arrows and, for all single-headed arrows, the word “ONLY” in the exiting lanes along approaches to movements with multiple exiting lanes. This practice, when combined with the use of dotted lane lines, provides additional aids to recognition of the change in lane state and destination, even when overhead signing is not visible.

Recommendation 4-3: Provide Solid Line Markings Upstream and Downstream of Decision Points

![]()

![]()

![]()

Solid lines discourage lane changes in critical areas, where drivers are navigating an exit ramp, also emphasizing the presence of multiple exiting lanes in areas where auxiliary lanes occur. Wide solid lane lines should be considered where operations exhibit excessive lane changes in these areas.

The implementation of these measures is not expected to considerably increase the cost of signing for interchanges.

Treatment 5 covers the following topics:

In conducting the practices evaluation and literature review, the project team identified practices related to sign panel legend selection and placement of the signs themselves that can contribute to driver-expectancy violations. Some of these are related to existing policy, and others are violations of existing practice literature likely borne of designer inexperience and insufficient familiarity with HFs guidelines. The notable undesirable practices are summarized in table 89.

Washington State, Florida, and Minnesota (project partners in the working group) have strong pavement marking standards development and integration into the design process. Each State differentiates between dotted lane lines and dotted extensions. All three States use lane-reduction arrows in conjunction with a physical reduction in the number of lanes, with Washington State using arrows along in a progressive fashion.

Part 3 of the MUTCD specifically differentiates between the dotted line and dotted extension markings in both the pattern and width. Dotted extension markings are also not required by a standard statement to be placed in the 1:3 ratio, and some States, including Minnesota and Washington State, have numerous installations using a 1:4 ratio to further differentiate the lane lines (e.g., solid lane divider line markings, dotted line markings, and broken line markings) from the guide lines.

In addition to researching the effectiveness of guide signs relative to lane choice, the simulator study also included several lane reductions. These lane reductions were treated in various ways to judge participant reaction to warning signs with a participant survey. The participant survey found that the majority of participants, including those who did not observe the sign in figure 81, interpreted the meaning of the sign to be that the lane was ending up ahead, in close proximity to the sign.

The W4-3X warning sign is a design that was developed for locations where tapered multilane entrances exist. While these are becoming less common, there are nearly 20 such instances in northeastern Illinois on roadway systems managed by 2 authorities, and other locations in urban areas where space constraints preclude the construction of multilane entrance ramps of the parallel type. This sign was not evaluated in the field because of construction conflicts at the evaluation site, but it is recommended for further study to replace the six designs observed in use in the United States. Future comprehension testing subsequent to a synthesis of signs is recommended.

Based on the practice evaluation and literature review, the project team is proposing further evaluations that specifically address warning sign placement and lane additions, in addition to pavement markings for entering and exiting lanes. The practice and research recommendations here are intended to apply the consistency principle in the placement of markings that convey the proximity of exits, the downstream duration and function of entering lanes, and their relationships to one another. In addition, these recommendations are predicated on the principle that warning signs should be sequenced so that they can function independently, as part of a system, and with or without associated markings, for all lane reductions. This enables practitioners to use just a single sign near the beginning of the lane-reduction taper, even if upstream signing cannot be provided.

Recommendation 5-1: Provide Sign to Indicate Beginning of Lane-Reduction Tapers

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A sign that warns about the location for the lane-reduction taper would help provide an enhanced warning in addition to pavement markings. Several potential signs could be used, and it is recommended that a consistent method be chosen. Figure 82 shows a MnDOT-designed sign, referred to here as the merge point sign (provisionally assigned MUTCD code W9-2A), that has been in use in work zones in Minnesota since the 1960s and, within the last decade, implemented in permanent installations as a means of clearly identifying the beginning of the lane-reduction taper. The high recognition score of the sign’s purpose, from the simulator study and an application that conforms to the consistency principle, indicates that this sign would be a useful addition to lane-reduction warning sign implementations. It is intended to be placed only adjacent to the outside lane to which it applies.

The sign is intended to supplement the upstream primary warning sign, the W4-2 pavement width transition symbol (see figure 83). The W9-2A sign is a replacement for the word message W9-2 sign and should be used opposite the W9-1L or R; the W9-2A simplifies the message for the motorist by providing a clear needful action.

Placement of the merge point sign, in contrast to the W9-2 and W4-2 signs, is uniformly located for all lane reductions. Such a consistent placement location, close to or adjacent to the beginning of the lane-reduction taper, aids motorists in identifying the taper in any situation where the sign is used. In situations where advance warning signs (e.g., the W9-1 sign) cannot be provided (e.g., short acceleration lanes associated with entrance ramps of the parallel design), the W9-2A sign can always be used in the location proximate to the beginning of the lane-reduction taper. With this consistent application, road users will always be able to identify their proximity to the lane-reduction taper and plan lane change and speed change maneuvers accordingly. Because lane-reduction tapers are based on speed, the placement of the sign relative to the beginning of the taper needs not vary on roadways with different speed limits and design speeds.

Recommendation 5-2: Provide Differentiated Pavement Markings

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

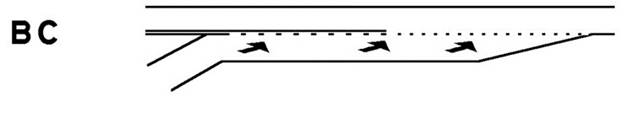

Provide differentiated markings for lane reductions that are dissimilar from the markings used for auxiliary lanes. For example, the use of the dotted lane line adjacent to a solid line would provide a pattern significantly different from the standard dotted line markings that separate auxiliary lanes from continuing lanes. The contrast between the entering lane forming an auxiliary exit-only lane and the entering lane forming an acceleration lane is illustrated in figure 84. Depiction BC illustrates the use of the solid line adjacent to the continuing lane, indicating that free access to the acceleration lane is not intended, as it is with the auxiliary exit-only lane in depiction B1.

B. An entering lane forming an acceleration lane.

Source: FHWA.

Figure 84. Graphic. Comparison of markings for auxiliary exit-only lanes and acceleration lanes.

Use of such a pattern on short- to medium-length acceleration lanes, with the solid line on the side of the continuing lanes, will indicate that the continuing lane traffic is not to cross over into the acceleration lane. In cases where acceleration lanes are marked with the dotted line, road users may mistake the lane as an auxiliary lane that continues to the next interchange and move into the acceleration lane.

Recommendation 5-3: Provide Lane-Reduction Arrows for All Lane Reductions

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Washington State, California, Florida, Minnesota, and several other States provide lane-reduction arrows in advance of physical reductions in the number of lanes. The lane-reduction arrow orientation sets the long axis of the arrow along the longitudinal center of the lane. Lane-reduction arrows are never used in auxiliary lanes terminating as exit-only lanes, where lane use markings are appropriate.

Recommendation 5-4: Improve Maintenance Practices

![]()

![]()

In most urban interchanges, high traffic volumes and the large fraction of lane changes typically lead to accelerated degradation of pavement markings. Several agencies provide for an “at-risk markings” biennial pavement marking renewal program, particularly in climates where snow removal is performed and ice control products are used. Targeted, limited renewal of solid lane lines, dotted lane lines, gore markings near the leading edge, and lane-reduction arrows ensures that TCD effectiveness is not reduced. This is particularly important in the spring, following winter snow removal, when wet roads further impede visibility.

The cost of retrofitting existing markings can be incorporated into existing maintenance activities; new construction will not incur significant additional costs. The cost of additional markings (e.g., word and symbol legends) is a marginal addition to new contracts and would be an addition to regular maintenance activities.

Treatment 6 covers the following topics:

In conducting the practices evaluation and literature review, the project team identified practices related to sign panel legend selection and placement of the signs themselves that can contribute to driver-expectancy violations. Some of these are related to existing policy, and others are violations of existing practice literature likely as a result of designer inexperience and insufficient familiarity with HFs guidelines. Some example practices that result in inconsistent design are summarized in table 90.

Addressing these issues may require changes to internal policy and procedures and may require modifications to specifications and special provisions for some types of contracts. In many cases, further guidance documents may be useful to encourage consistent practices.

While practitioners should determine appropriate policy and practice recommendations concerning the design, approval, fabrication, and installation of signs, it is important to do the following:

The implementation of these measures is not expected to considerably increase the cost of signing for interchanges when incorporated early in the design process.