This section is intended to help local government officials actually institute a noise compatibility land use control program which would use one or more of the administrative techniques discussed in Section 3 to bring about chosen physical methods discussed in Section 4. Accordingly, this section is divided into three parts:

The actual effort necessary to determine and implement a noise compatibility control program for a specific community involves analysis of the various possible physical and administrative techniques in order to choose the combinations that will best suit the local situation. This work can be done by an elected official, by a member of the municipal staff or by a citizen committee appointed specifically for this reason. The amount of analysis and the type of action taken in this effort is dictated primarily by the urgency of the community’s potential noise incompatibility problem:

Another dimension can be added to the administrative process by the inclusion of master planning. Master planning provides the important advantage of considering the various noise compatibility control options as part of a larger set of community goals and plans. As such, master planning can identify and avoid situations where certain noise compatibility control measures would conflict with other community goals.

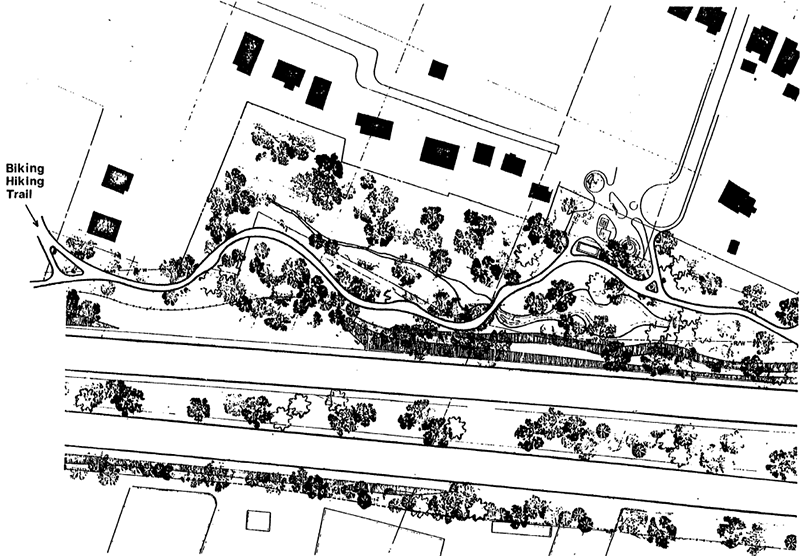

In its master plan, a community or regional planning agency can guide the development of the town or region to minimize noise impacts. For example, it can recommend that industrial and commercial uses and open space recreational areas be located along highways, and residential areas be placed in quieter zones. Linear parks along a highway can provide needed open space for the community and natural beauty for the passing motorist. They can also provide a good use for land which is too noisy for residential development. An example of an effective use of linear parks with playgrounds, biking and hiking trails, and ponds is shown in Figure 5.1.

* Provided by Environmental Planning and Design of Pittsburgh

Master planning does have some significant drawbacks which make it impractical to implement in all communities.

Inclusion of noise compatibility land use control considerations into any local master planning effort is most desirable. It is not, however, adequate unless the administrative controls necessary to implement the master plan are adopted and immediate noise incompatibilities are dealt with.

A strategy of normal administrative implementation can be divided into five major phases:

Timing is crucial in this strategy. Several of the most desirable physical solutions, such as buffer strips, acoustical site design, and acoustical construction methods, become impractical or impossible once incompatible land uses have been located near highway noise sources. Also, many of the administrative techniques such as zoning are not applicable once development has started or has reached the advanced planning stage. Thus, it is most important for a community to begin its noise compatible land use control program well before the potential incompatibilities exist.

Identify the Problem: Existing and potential noise incompatibilities can be identified by determination of both noise levels and potential land uses in noise impacted areas. Usually this can be done without employing an acoustical consultant, and often the larger and better staffed localities may wish to have their own measuring equipment. Noise levels often can be determined from state highway department data. If some technical skill is available within the municipal staff, the noise predictors listed later in this section will be helpful.

The master planning process can provide assistance at this point by providing an inventory of existing and potential land uses in noise impacted areas and by defining noise compatibility goals for the community. Typically, these goals will be based both on ideal compatibility standards and on realistic practical limitations imposed by the local conditions. Hence, the earlier the planning process is started, the less restrictive these limitations will be.

Examination and Selection of Administrative Techniques Suited to the Locality: The existing local administrative structure should be studied to see which of the administrative techniques listed in Section 3 of this manual are presently possible. If an existing administrative structure exists capable, with minor change, of implementing the most desirable physical solutions, the implementation process becomes relatively easy. For example, if the community is experiencing rapid growth and developers are anxious to build, the town’s subdivision rules and regulations could be rewritten to incorporate noise reduction considerations, and building permits could be made contingent upon strict compliance.

Study of Legal Status: If existing administrative structures are not capable of implementing the most desirable physical solutions, the next step would be to determine what administrative mechanisms could be set up under the state’s laws.

For example, a community might be able under state law to assess undeveloped land at a low value, thus providing a financial incentive. Or, a community might decide to adopt zoning or subdivision control to implement noise compatibility control. If the necessary administrative procedures are not permitted by state enabling acts, pressure can be applied to revise the state legislation.

Implementation: If an acceptable new administrative technique can be adopted capable of implementing noise compatibility control programs, the implementation process now becomes relatively easy. What is needed, however, is constant re-evaluation of the noise compatibility goals and possibly the master plan.

The problems posed by the introduction of incompatible land uses to areas near existing noise sources highway or otherwise are significant in terms of economics, health, and quality of life. The solutions available are many, especially before any land development has taken place. It would seem that this combination of significant potential problems and readily available solutions is a clear indicator that the goals of the manual will be achieved rapidly in all parts of the country.

However, this may not be the case: The obstacles to the implementation of this manual are many and must be overcome if noise-compatible land use development is to be possible. They include:

Public Apathy: It is an unfortunate fact that little public awareness of noise incompatibility exists. The resulting apathy makes it difficult for officials to implement noise compatibility programs, especially when high municipal costs or extensive restrictions are involved. The term “noise pollution” is a relative newcomer to popular environmental jargon, having got a much slower start than air and water pollution. It is now becoming increasingly more the subject of public attention. Perhaps this increasing public awareness will soon overcome existing apathy. Until then, local officials can make efforts through the press or through citizens’ groups to inform the public of the significant financial and social costs of noise incompatibility.

Legal Limitations: Legal limitations exist on powers of local governments to restrict and regulate land use control. The powers granted by state enabling acts vary greatly from state to state. Such things as occupancy permits, required environmental impact statements, and incentive tax assessments are not legal in all states. This obstacle can only be overcome by action in the various state legislatures.

Cost: The adoption and enforcement of any regulation or restriction will entail administrative costs. This can include legal costs and court ordered payments if lawsuits result from improper administration of regulations. Finally, the costs of municipal land purchase can be significant.

A careful choice of administrative noise compatibility control techniques can minimize these costs. Often a combination of techniques is less expensive than a single technique. For example, a policy of zoning restrictions combined with municipal purchase of only the most threatened land is far less costly than a policy of massive municipal purchase. Likewise, the costs of administering and enforcing a health code noise regulation could be lessened if the community also had an architectural review board which inspired builders to voluntarily construct noise compatible dwellings.

Negative Side Effects: While some noise impact reduction techniques, such as linear parks in a buffer zone, are aesthetically pleasing, other techniques, such as high barrier walls, can be eyesores. Likewise, the sealed environment within an acoustically insulated house, or the enclave effect created by extensive barrier walls can be quite displeasing to the residents. All of these negative physical effects can be overcome in many instances if planning for a noise compatibility control program is begun early enough to allow a wide variety of physical techniques and if the administrative structure is such that a choice can be made between the various physical techniques. However, in situations where there is an inflexible administrative system or extensive existing development, the limited choice of physical techniques will make some negative side effects unavoidable.

Private Interests: Most noise compatibility control programs inevitably restrict the options available to builders, developers, and owners of land near a highway. As such, these people will have a natural opposition to the program and may exert pressure against its adoption. This opposition can be neutralized by seeing that the restrictions are limited to only those that are necessary, offering practical alternatives such as cluster development, and by informing the public of the relevant issues thus enlisting public support for the program.

Tradition: Lastly, a noise compatibility land use control program may represent a sharp break with established local tradition. Zoning, restrictive codes, municipal land purchase, and various physical techniques all may be new concepts in a community. Such traditions are often tenaciously held, and an extensive public information effort may be required to break them. Usually, a clear knowledge of all of the effects of a program will lessen the public fears associated with it.

For additional information on issues of highway noise control, there are a number of useful sources which provide comprehensive information in the areas of acoustics, the effects of noise, noise standards, prediction techniques, impact reduction techniques, and noise control legislation.

The Fundamentals and Abatement of Highway Traffic Noise1 is an excellent general text on highway noise providing basic technical information on most of the areas mentioned above. For a less technical, more general review of acoustics and noise control, Noise2 by Rupert Taylor is highly recommended. Two texts which provide a comprehensive review of findings on the effects of noise are Noise as a Public Health Hazard - Proceedings of the Conference,3 a publication of the American Speech and Hearing Association; and the Report to the President and Congress on Noise.4 Community Noise5 contains information on the community’s reaction to noise. A review of studies to determine compatible noise levels is contained in Evaluating the Noise of Transportation; Proceedings of a Symposium on Acceptability Criteria for Transportation Noise.6

For a review of Federal Noise Standards, see (a) The Noise Control Act of 1972,7 (b) HUD Circular 1390.2, “Noise Abatement and Control, Department Policy and Implementation Responsibilities and Standards,”8 and (c) the FHWA Policy and Procedure Memorandum 90-2: “Noise Standards and Procedures.”9

Two highway noise prediction techniques are described respectively in (a) Manual for Highway Noise Prediction,10 and (b) National Cooperative Highway Research Program Report #117, Highway Noise: A Design Guide for Highway Engineers.11

Texts on physical techniques for noise impact reduction tend to concentrate on specific techniques. A relatively comprehensive text on physical techniques is Environmental Acoustics12 by Leslie T. Doelle. This book contains acoustical information on site planning, architectural design, and building construction. The Handbook of Noise Control13 also provides a somewhat comprehensive coverage of noise control techniques. It is particularly useful for the article on acoustical construction entitled “Transmission of Noise Through Walls and Floors” by R.K. Cook and P. Chrzanowski. Two important documents on acoustical construction techniques are Guide to the Soundproofing of Existing Homes Against Exterior Noise,14 and A Study of Techniques to Increase the Sound Insulation of Building Elements.15

For extensive descriptions of various types of noise barriers, see Highway Noise Control: A Value Engineering Study.16 The Fundamentals and Abatement of Highway Traffic Noise described above also contains an informative discussion on barriers. For a comprehensive overview of the use of plants in design and noise control, see Plants, People, and Environmental Quality.17

Although it is not directed at noise control, Cluster Zoning in Massachusetts18 contains useful illustrations of cluster zoning techniques, some of which can be used to reduce highway noise impacts.

Informative literature on administrative techniques for local government noise compatible land use control is scarce. The most helpful literature for further study in this area is legislation.

On the Federal level, the National Environmental Policy Act of 196919 requires environmental impact statements, which include noise impacts, for certain Federal projects. On the state level, local governments should review their state enabling acts that allow the various administrative techniques described in Chapter 3. In addition, the State of California’s Environmental Quality Act20 provides an example of a state requirement for environmental impact statements for all public and private development.

Some local legislation which may be useful as examples of noise compatible land use control are the Development Standards for the City of Cerritos,21 and the Health Code of Orange County.22 These and others are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

1 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Fundamentals and Abatement of Highway Traffic Noise, June 1973, Report No. FHWA-HHI-HEV-73-7976-1.

2 Rupert Taylor, Noise, Dell, 1970.

3 W. Dixon Ward and James E. Fricke, eds. Noise as a Public Health Hazard—Proceedings of the Conference, ASHA Reports 4, The American Speech and Hearing Association, Washington, D.C., February 1969.

4 U.S. Congress. Senate. Report to the President and Congress on Noise, S. Doc. 92-63, 92nd Congress, 2d session, 1972.

5 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Community Noise, December 31, 1971. Report No. 69-04-0046.

6 Chalupnik, James D. (ed.), Evaluating the Noise of Transportation; Proceedings of a Symposium on Acceptability Criteria for Transportation Noise, Washington, D.C., April 1970.

7 Noise Control Act of 1972, P.L. 92-574 October 27, 1972.

8 Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD Circular 1390.2, “Noise Abatement and Control, Departmental Policy Implementation Responsibilities and Standards,” Washington, D.C., August, 1971.

9 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Policy and Procedure Memorandum 90-2, “Noise Standards and Procedures,” Transmittal 279, February 8, 1972.

10 U.S. Department of Transportation, Transportation Systems Center, Manual for Highway Noise Prediction—Technical Report, Washington, D.C., 1972.

11 National Cooperative Highway Research Program Report #117, Highway Noise: A Design Guide for Highway Engineers, Washington, D.C., 1971.

12 Leslie T. Doelle, Environmental Acoustics, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1972.

13 Cyril M. Harris, ed., Handbook of Noise Control, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1957.

14 Los Angeles Department of Airports, Guide to the Soundproofing of Existing Homes Against Exterior Noise, Report No. WCR-70-2, March 1970.

15 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, A Study of Techniques to Increase the Sound Insulation of Building Elements, June 1973, Report No. NR-73-5.

16 California Division of Highways, Highway Noise Control: A Value Engineering Study, October 1972.

17 U.S. Department of the Interior, Plants, People, and Environmental Quality, 1972.

18 Kulmala, Katharine A. (with the Planning Services Group, Inc.), Cluster Zoning in Massachusetts, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1970.

19 National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. p. 6, 92-574 (October 27, 1972).

20 State of California, California Administrative Code, Title 14. Natural Resources, Division 6, Chapter 3.

21 City of Cerritos, California, Development Standards of the City of Cerritos.

22 Orange County, Health Code.