The discussions of administrative techniques and physical methods in earlier sections of this manual emphasized the need to consider specific local conditions in selecting an effective strategy for reducing highway noise impacts. To illustrate variations in community requirements and to evaluate some strategies that have been or might prove to be effective, case studies of three communities’ efforts to control noise impacts were carried out as part of the preparation of the manual. Within each community, a parcel of undeveloped noise impacted land was chosen for specific focus. The communities selected Somerville, Massachusetts; Cerritos, California; and Marshfield-Pembroke, Massachusetts-represent widely divergent population densities, community backgrounds and goals, political environments, state laws, and topographical characteristics. From these case studies, it can be seen how these factors shape the noise reduction strategies chosen and their relative successes.

Population density seems to be a major determinant of a community’s strategy. The low density of Marshfield-Pembroke, the medium density of Cerritos, and the high density of Somerville clearly are reflected in the three respective chosen strategies of zoning, barrier construction with residential sound insulation, and site planning in an urban renewal situation. Although these three communities were not chosen on the basis of population density, they clearly demonstrate the effects of this variable.

The local political environment and community goals constitute another major determinant of noise compatibility control strategies. In Cerritos, a powerful and capable local government, supported by public attitude, has been able to implement land use controls that would not be possible in many other communities. Marshfield and Pembroke, with the open town meeting and part time municipal officials, provide an excellent example of strong citizen control over the policies that the town officials can implement. The technique of zoning the potential noise impact area for industrial uses only may have to be reversed at a later date. Any changes to this strategy face the possibility of battles on the town meeting floor and all of the uncertainties that the open town meeting provides. The third case, Somerville, is an example of how local community and political pressures have forced a change from a strategy of urban industrial zoning to that of acoustically protected residential use.

The town’s maturity also plays a role in determining the land use strategies involved. Incorporated in 1956, Cerritos is a relatively young town which is experiencing intense pressures for development. Because development is occurring at such a rapid pace, the public is aware of the need for controlled growth and the importance of environmental considerations. Also, developers realize that if they want to build, they must comply with stringent noise compatibility standards. In contrast, Somerville is an old city with most of its housing constructed before 1940. It developed without specific regard to noise compatibility problems which have only recently become matters of concern. Unfortunately, residential areas and traffic patterns are established, and it is therefore difficult to deal effectively with traffic noise problems.

A final major determinant of the techniques which a locality can utilize to promote land use compatibility with noise is the existing state legislation in this area. California, for example, has both a powerful environmental quality act which applies to almost every construction project, and a strict requirement that each community have an extensive local master plan. The Cerritos case study shows the effect that this type of support can have on the local government’s ability to act in a forceful manner.

The three case studies all show that highway noise and adjacent land compatibility is an existing or potential problem. While there is a wide range of people’s perception of the problem and an equally wide range of possible solutions, the problem is real and must receive careful local attention.

Each case study follows the same basic format:

They are presented successively below.

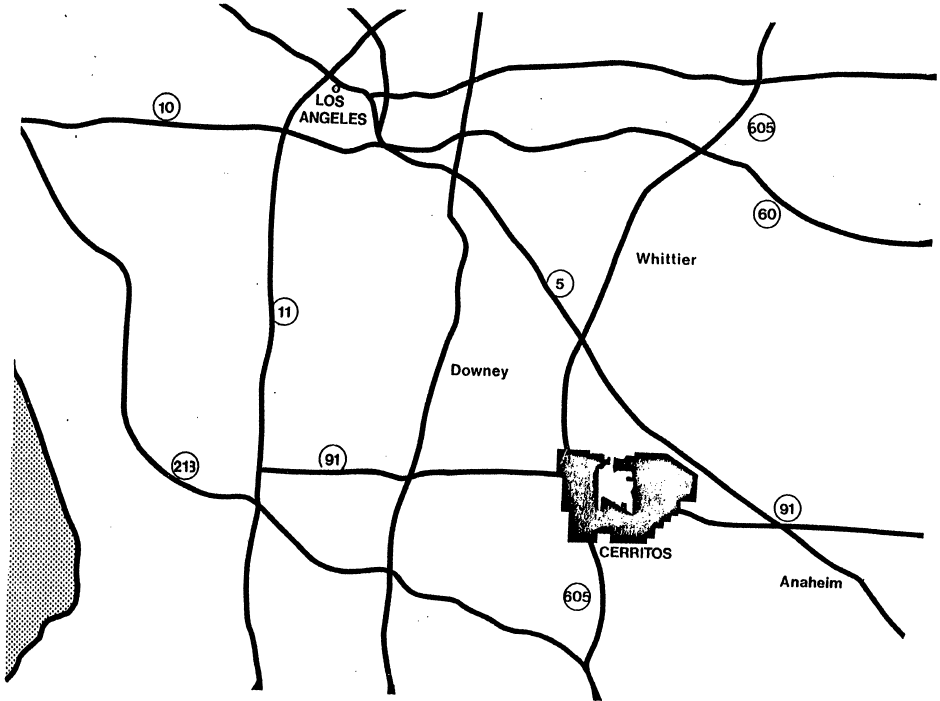

Cerritos, California, located in suburban Los Angeles County, is a rapidly developing residential community facing severe highway noise impact from three major freeways (see Figure A-1). A construction boom has transformed Cerritos from a dairy farming community of less than 4,000 people to a city of 40,000 in less than a decade. The residents are primarily young, well-educated middle and upper-middle income families. Although the demand for new homes has led to residential development in noise-impacted zones adjacent to the freeway right of way, the problems of highway noise have not been ignored. An active city government with strong public support has endorsed stringent noise standards for new residential construction. Developers are required to incorporate acoustical considerations in site planning and architectural design, to use sound-proofing construction materials and techniques, and to erect noise barriers.

Role of Local Government: Although Cerritos is not unique in having land use and land development as key political issues, its city government has responded to these issues in an unusually effective manner. The government has an executive and legislative form of government consisting of a city manager and city council respectively. It has a Department of Environmental Affairs which contains a city planning staff of eight full-time employees, a considerable number for a city its size. The planning staff takes a very active role in all aspects of urban development in Cerritos. Its activities go beyond the formulation and enforcement of the general plan for land uses. Plans for development of particular land parcels are scrutinized at all levels from overall site planning to construction materials and architectural details. In fact, the City of Cerritos acts in many ways as a site planner and architectural consultant to all new developments, and has even taken over some of the roles usually performed by real estate developers. In its unusual role, the Department of Environmental Affairs has the support of the five-member Planning Commission and the political backing of the City Council. One of the principal levers used by the City to guide the development is the building permit. All building permits must be approved by the Department of Environmental Affairs which frequently withholds its consent until plans are revised to conform to its specifications.

The City Government’s active role in improving the physical environment of Cerritos includes stringent measures to control the problem of noise. City ordinances restrict noise emissions; the general plan and zoning laws control noise incompatible land uses; and building codes give detailed prescriptions for noise reducing construction techniques. The basic tool for achieving these ambitious goals in noise reduction is, once again, the city planning staff which provides technical and planning assistance as well as control and supervision.

The Role of the State Government: The state of California assists in the control of noise incompatible land uses through two important statutory requirements. California requires local communities to adopt detailed general plans for development. In addition to such items as land use, housing, conservation, and open space, the plan is specifically required to contain a noise element. The noise element forces local communities to consider the problem of noise compatibility in planning land uses. There are many difficult obstacles to overcome in converting general or master plans into actual land uses. The State of California has taken a first step to encourage the implementation of general plans by requiring that local zoning maps be brought into conformance with the land use patterns adopted in the general plan. Once this occurs, zoning changes or variances cannot take place without previously revising the general plan.

The second major state contribution to encouraging noise compatible land use is the California Environmental Quality Act. This law requires a detailed Environmental Impact Report to be prepared for all major new construction projects, whether public or private. With a few minor exceptions, such as individual single-family homes or individual apartments of four dwelling units or less, the developer of any parcel of land must submit a detailed, documented analysis of any potential negative environmental impact. The Environmental Impact Report must be approved as adequate by local government authorities, a process which may require several revised submissions, and public hearings. With respect to noise, the EIR requires analysis of the impacts of the existing environment upon the project, the impact of the project upon the surrounding area, and the development of specific measures to minimize any negative impact.1

Discussions with California state and local officials indicate that the requirements of the Environmental Quality Act have helped educate local officials and real estate developers about the nature and magnitude of environmental impacts on the surrounding community. As a result, both local government and private entrepreneurs have become much more sophisticated in developing alternative plans to reduce environmental impacts. In addition, the EIR provides local communities with the information they need to estimate accurately the level of environmental degradation. In the case of noise there is now a much greater understanding of noise measurement techniques and the evaluation of the acceptability of noise levels, as well as sufficient data on individual sites to make informed judgments possible.

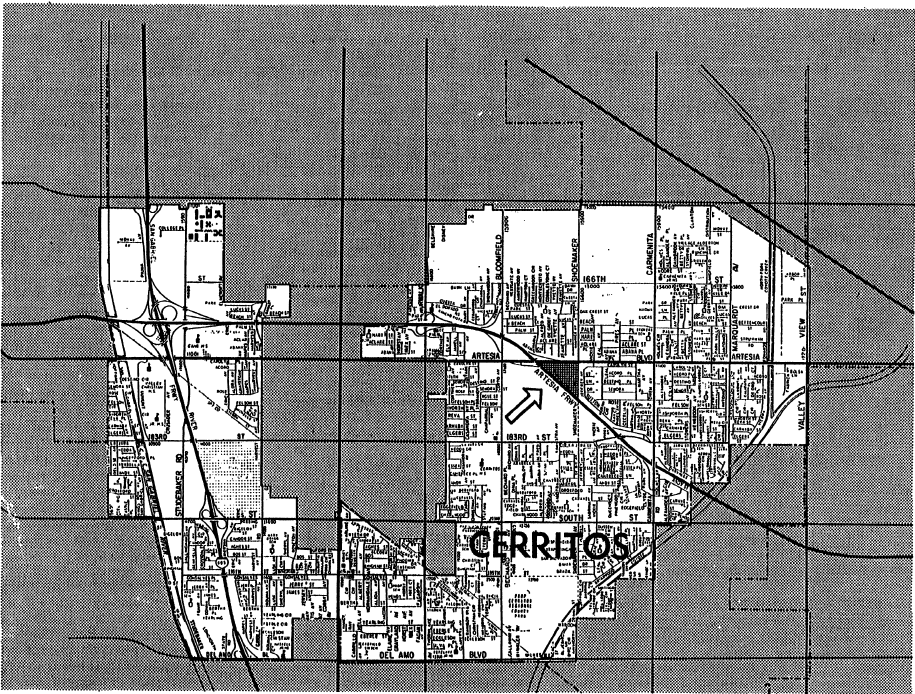

Noise Sources: The principal noise sources in Cerritos are three major freeways: the San Gabriel Freeway (Interstate 605) in the western half of the city, the Artesia Freeway (Interstate 91) crossing the center of the city in an east-west direction, and the Santa Anna Freeway which is adjacent to the northeast corner of the city. These highways are heavily traveled by passenger cars and trucks and cause major noise impact along their borders. The land uses along these freeways are mixed, but include substantial amounts of residential development. (See Figure A-2).

Arterial streets in Cerritos are also heavily traveled and create another source of noise, although their impact is much less than that of the freeways. Neither Long Beach Airport seven miles away nor Los Angeles International Airport twenty-five miles away creates a severe noise impact. There are no stationary noise sources at the present time.

The City of Cerritos has established ambitious standards for dealing with the severe problems of highway noise. Ambient noise levels of 45 dBA within dwellings, and 60 dBA in outdoor residential areas, are standards advanced in the city’s general plan.

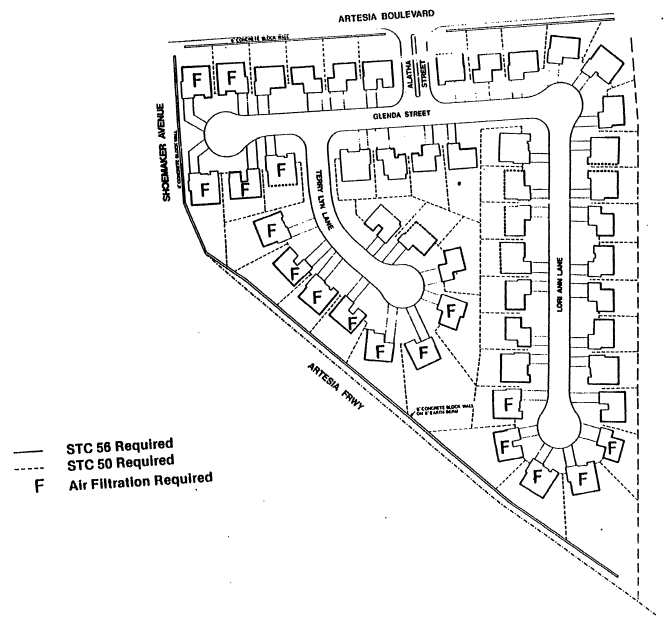

The Study Site: To illustrate some of the highway noise problems facing Cerritos, and to analyze some of the efforts being made by that community to solve them, it is useful to examine a specific site. A residential development currently under construction in the northeastern section of Cerritos provides a good example. Tract 29444 covers a roughly triangular area of about 12 acres. It is bordered on Cerritos, Cal. the north by Artesia Boulevard, on the east by the proposed extension of Schoemaker Avenue, and on the southwest by the Artesia Freeway (California Route 91). (See Figure A-2) Like most of Cerritos, this area was once dairy farmland. It is now zoned for low density (2-5.5 units per acre) residential use, and a subdivision of 49 single-family homes is currently under construction on this site.

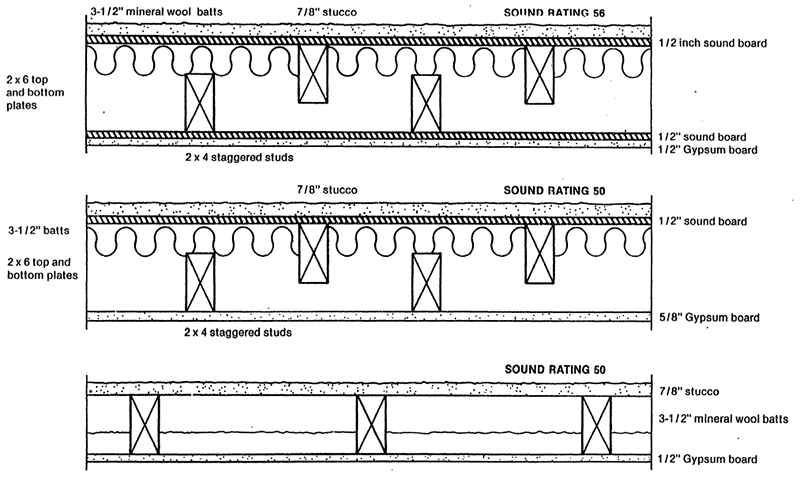

Noise from motor vehicles was one of the critical constraints in the planning of this subdivision. Traffic on well-traveled Artesia Boulevard creates a noise pollution problem, but the critical difficulty is presented by the Artesia Freeway which directly abuts the tract. Even the third border on the development site, while currently vacant and therefore not a noise source, is planned as a major city street to be constructed in the future. In the face of all these noise sources, developing this small tract of land to meet residential noise standards is a formidable task. The city of Cerritos has insisted on the use of a wide range of noise reduction techniques in the design and construction of these houses in order to meet the city’s objectives of obtaining an ambient noise level of 60 dBA in open spaces relating to dwellings, and 45 dBA within dwellings. Before granting building permits, Cerritos’ city planners carefully scrutinized building plans and insisted on specifying a variety of sound reducing design and construction features. Some of these changes are illustrated in the tract plan (see Figure A-3):

Each of these techniques was worked out in negotiations between the city planning department and the developer. Three factors may be cited in the success of these negotiations in achieving satisfactory noise levels:

Although the plans implemented for Tract 29444 have achieved their acoustical objectives, they do raise questions of economics and aesthetics. The cost of noise reducing construction and design adds a premium of about 10% to the price of these homes compared to similar residences built in less noise impacted areas. (This premium excludes the cost of air-conditioning and other improvements which are not solely noise related.) The aesthetic costs of noise reduction are much less quantifiable, and in fact are a matter of individual taste. The high concrete walls and reduced window space tend to create a closed-in environment which some might find cold and forbidding. Most people would agree that the high noise barriers on top of earth walls are not an ideal back-yard environment. The additional economic costs and aesthetic limitations must be traded off against the real benefits of a greatly improved noise environment. Considering the popularity of similar developments in Cerritos it is likely that Tract 29444 will be a popular success.

Action for Noise Reduction: Cerritos, California’s program for highway noise compatibility control utilizes a wide variety of techniques. Three aspects of Cerritos, Cal. this approach stand out as most important in evaluating its applicability to other communities: strict legal controls, active municipal design review, and the implementation of noise reducing construction techniques.

Strict legal controls on noise in Cerritos result from a variety of state and local laws and regulations. Some of the most important mechanisms are the Environmental Impact Report required by state law and implemented by local government guidelines which result in planning for noise in the initial stages of project design; the general plan for future development which is backed-up by strict zoning ordinances; and a variety of local noise regulations aimed at the specific noise problem and adapted to local land use and construction patterns. Many of these guidelines could be adopted in other communities with minor modifications, if local and statewide political support are available. The most difficult aspect of the Cerritos environment to transfer is the political commitment on the part of public officials to solving noise problems.

Cerritos’ approach to noise problems emphasizes the act of participation of city planners in all development activities to ensure that environmental and aesthetics standards are being achieved. This active planning role, in which the City government sometimes appears to perform many of the functions of a private developer, is possible only because of the high level of skills of city planning officials and successful only because the demand for land in Cerritos is so intense that developers are constrained to cooperate with the city. While other communities may possess the skill to form this planning role, they may find it difficult to achieve the same high level of cooperation on the part of private developers. The role of the Cerritos city government in helping to educate developers and architects about noise reduction techniques can certainly be adapted to other communities.

Cerritos’ implementation of noise reducing construction techniques provides important lessons for other communities. Significant levels of noise reduction have been achieved in residential developments without destroying their economic viability. Some of these techniques could be applied anywhere in the United States. Others, such as air conditioning, would raise questions of economic viability in other areas. The widespread use of concrete noise walls may be more difficult to transfer to other locations. In Cerritos, these walls are not out of place with the dominant Southern California architectural styles. In many other parts of the country, however, the lack of open space and the inward-looking courtyard effect of the noise wall may be aesthetically unacceptable.

One important technique for noise impact reduction which has not been applied in Cerritos is the prohibition of noise-sensitive uses, particularly residences, in high-noise zones. The Cerritos general plan specifically rejects the option of placing industrial uses along the freeway borders, because it wishes to preserve continuity with existing residential developments adjacent to these areas. It has instead, chosen to isolate industrial uses in sections away from residential areas.2 This decision emphasizes once again that noise considerations, even in the most environmentally conscious communities, are not the sole criteria for land use planning.

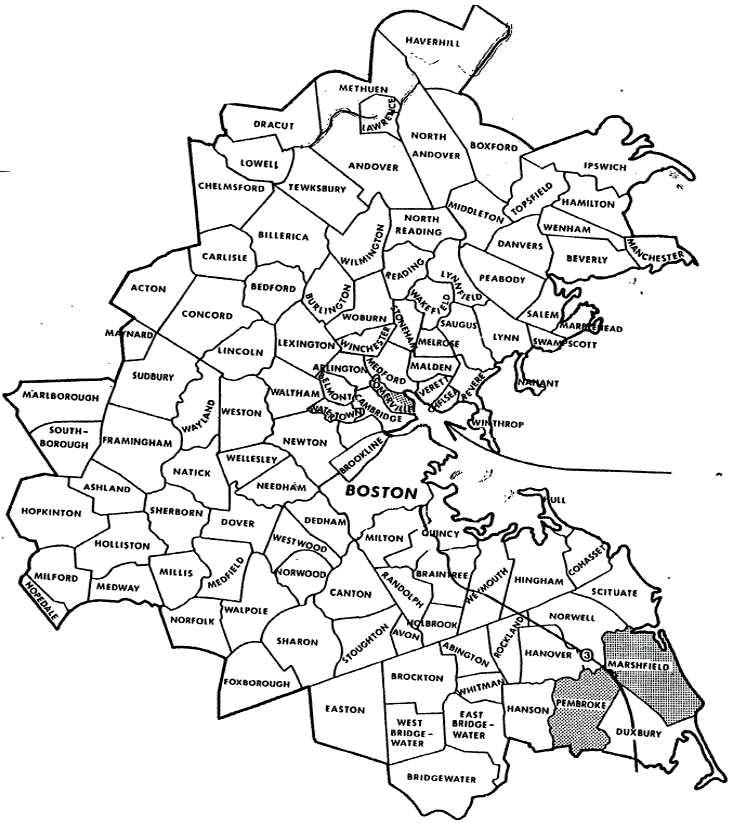

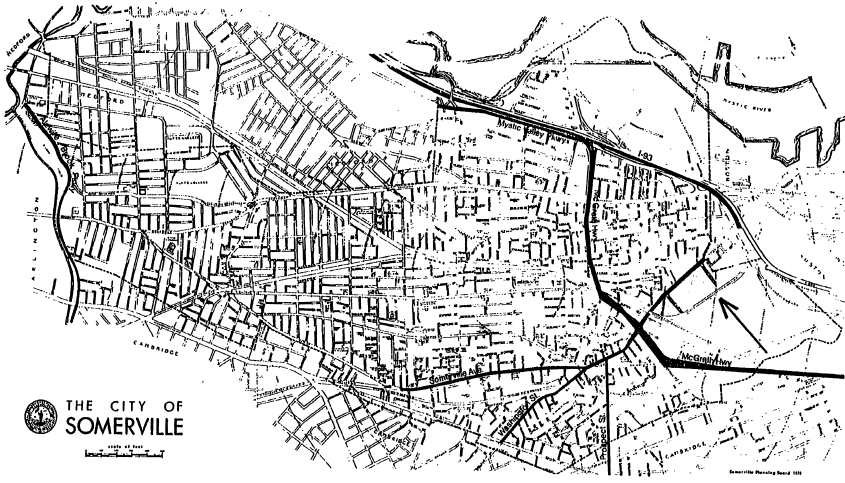

Somerville, Massachusetts, located 3 miles from downtown Boston, is an old urban residential community with a declining population. (See Figure A-5) Its residents, primarily middle income and consisting largely of elderly people and young transients, are only recently becoming concerned with highway noise due to the construction of Interstate 93 through the heart of a densely populated residential area. Until the recent citizen concern, the local government has done little to reduce noise impacts. The whole issue of noise pollution is relatively new, and, in any case, the city has been almost entirely built up for several decades, leaving little opportunity to change land uses to ones that are noise compatible. The City of Somerville has no noise control laws; the only significant noise standards are those set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development from which the city has sought funding.

Role of the Local Government: At present, there is a trend towards new housing construction in Somerville, largely due to the strong support of the Mayor. It is possible that, although Somerville has done little to regulate noise compatible development to date, concern for such regulation will increase in the future because of the city’s need for new federally assisted housing.

Role of Federal and State Government: When Federal funding is required for construction of projects such as housing or schools, the projects must satisfy environmental impact requirements, which include noise criteria. With regard to highway noise, developers must show that noise levels are within levels which the Department of Housing and Urban Development considers to be compatible with the project. In the case of the Inner Belt Urban Renewal Project, traffic noise levels are presently too high for HUD’s approval. Funds are being withheld until the developer can reduce the noise impact to compatible levels. This case study describes the administrative and physical techniques used by the City of Somerville to reduce noise impacts on the urban renewal site to compatible levels.

The City of Somerville also has frequent dealings with the State of Massachusetts. Somerville and the Massachusetts Department of Public Works have been involved in controversies over the location of state highways in Somerville. The Department of Public Works has the power to locate and relocate roadways. Two highways which have directly affected the project site under consideration are Interstate 695 and Interstate 93.

Somerville’s housing stock is obsolete: 90.1% of its units, mostly wooden two-family houses, were built before 1939. Thus, Somerville has not attracted new residents who might profit from the city’s proximity to Boston. In fact, since 1950, Somerville has experienced a 13% decline in population, and economic opportunities have been restricted by the lack of space for industry.

The only land available for redevelopment was recently changed from an industrial to a residential use. This site, known as the Inner Belt Urban Renewal Project, is the focus of the case study. It demonstrates, among other things, the effectiveness of an executive-legislative form of government in implementing change. The study site was originally zoned industrial because of plans to build a highway nearby. However, the highway plans were discontinued leaving the spot unmarketable for industry and yet too noisy for residential use because of heavy truck traffic on adjacent roads. The need for housing and the mayor’s influence changed the site’s future from industrial to residential. A federally funded low income housing project is planned, thus making the site subject to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s noise compatibility guidelines.

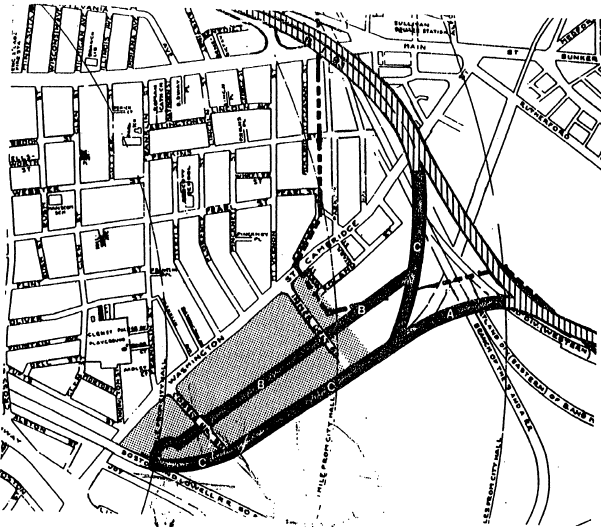

Noise Sources and Levels: In recent years, Somerville has been frequently confronted with the problems of highway location and highway noise. Because of the importance of wholesale and retail activities to the local economy, much trucking takes place giving several streets extremely high noise levels. Among these are Mystic Avenue, Prospect Street, and Alewife Brook Parkway. In addition, there is heavy truck traffic on the McGrath Highway and on I-93. A map showing the distribution of these noisy streets follows in Figure A-6.

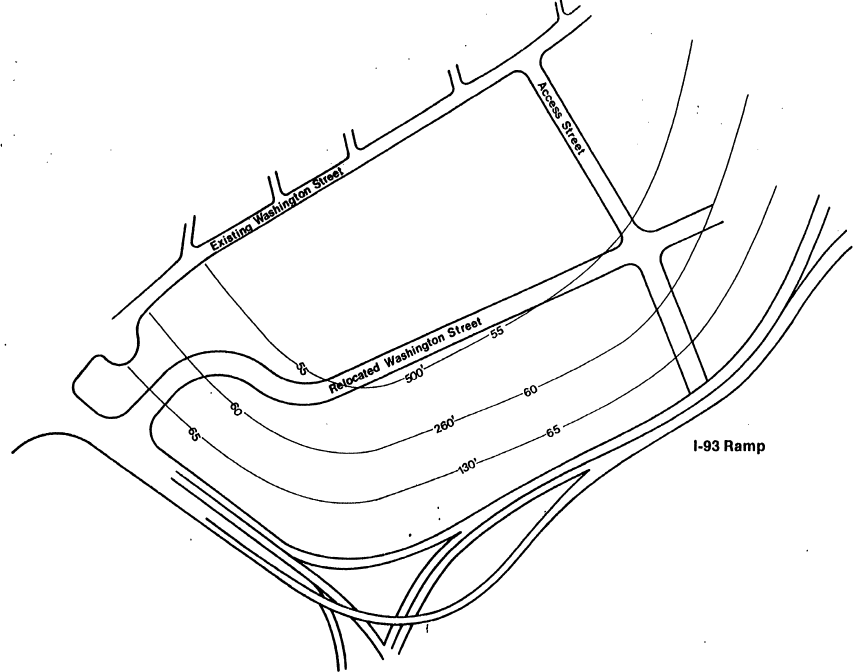

Interstate 695, the “Inner Belt,” was planned to link communities inside Route 128, and connect Interstate 93, approaching Boston from the North, with Interstate 95. It was designed as part of the 1948 Master Highway Plan for Metropolitan Boston. First the route, and then the rationale for the Inner Belt were questioned by the communities through which it was to have been built. In January 1969, Governor Sargent stopped work on it, and on February 11,1970 he declared a moratorium on all major highway projects inside Route 128 which were not yet underway. Unfortunately, Somerville and other communities had already made plans which depended on the construction of I-695. For example, the Inner Belt Urban Renewal Area was to be bordered by the Inner Belt, making it ideal for industrial development. But when the Inner Belt was cancelled, the site proved unmarketable for industrial uses. Furthermore, under the present heavy truck traffic conditions and consequent noise around the site, the site is also unsuitable for housing, and will not receive funding from the Department of Housing and Urban Development until noise impacts are reduced. The success of the present residential plan depends upon the relocation of Washington Street south of the project site and the special location of a proposed I-93 off-ramp near the site. Thus, the future of the project depends upon the decisions of the Department of Public Works.

The Case Study Site: The Inner Belt Urban Renewal Project is a 23-acre urban renewal block located in East Somerville. It is bordered on the north by Washington Street, on the west by the McGrath Highway and on the south and east by the Boston and Maine Railroad. (Figure A-6) It is zoned for industrial use, but current plans include a mixture of residential, office, and commercial facilities. It was initially zoned industrial due to its proximity to the Boston and Maine railroad tracks and the proposed location of Interstate 695, the inner beltway. In addition, an industrial park is located south of the project area.

Under present conditions the Somerville site is extremely noisy. It is the noise created by the heavy truck traffic on Washington Street which runs along the entire northern boundary of the site which is the most serious, as the amount of land fronting on McGrath Highway is small, and railroad service in the site area is infrequent. An additional noise problem is that presented by a projected Interstate 93 off-ramp which will be located near the project area, as well as the industrial park located south of the site.

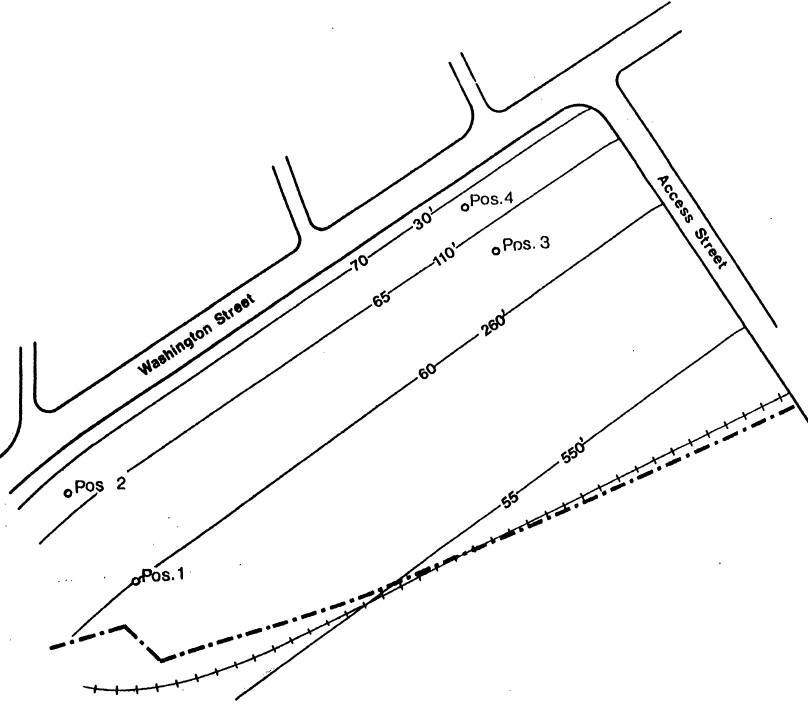

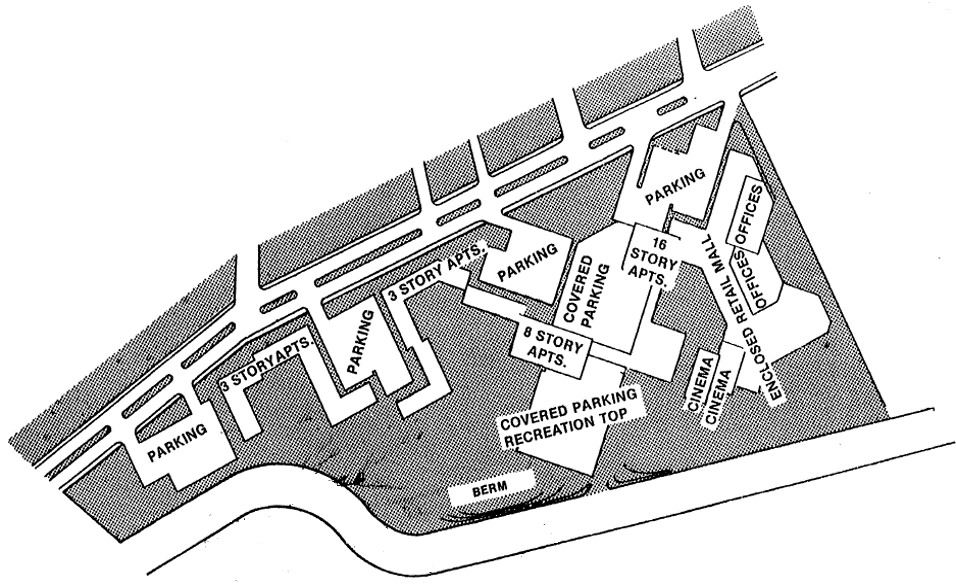

According to the preliminary environmental impact report prepared for the Somerville Redevelopment Authority, there is no external location on the Inner Belt Urban Renewal site which falls unequivocally in HUD’s “clearly acceptable” category.3 Furthermore, the area within 110 feet of Washington Street would be Discretionary normally unacceptable4 for housing because of its exterior noise levels. The rest of the site falls in the category of Discretionary normally acceptable.5 The present noise contours on the site are indicated in Figure A-7. The site plan employs two major techniques of noise reduction:

If Washington Street were relocated south of the site, and Alternative “C” were chosen for the ramp location, the entire site would then be classified by HUD as discretionary normally acceptable6 due to the proposed I-93 ramp. New Washington Street will have less truck traffic than is presently on Old Washington Street. Furthermore, the reduction and possible removal of traffic from Old Washington Street will have the advantage of tying together the residential neighborhoods of East Somerville and the project area. And a relocated Washington Street would serve as a buffer between the project area and the Inner Belt Industrial Park. (See Figure A-10) Also the choice of Alternative “C” for the off-ramp would have the least noise impact on the site.

Another noise reduction method which is being considered by the Massachusetts Department of Public Works is to depress New Washington Street several feet below the site. This would also have the advantage of removing the visual impact of passing truck traffic from much of the site. If the road is depressed, the site plan envisions erecting a berm along the roadway to create a noise barrier equivalent to one story when one combines the height of the berm and the depth of the roadway. The cost of such a berm is felt to be quite small as the necessary earth would already be on the site.

Other Possible Solutions and Why They Were Not Applied: Due to cost constraints, site planning has been the major means of noise reduction considered by the architect. Other alternatives such as barrier construction and soundproofing were eliminated because of their expense.

It would be possible to use stronger site planning techniques to minimize noise. Putting all of the nonresidential facilities along New Washington Street would create a more effective noise buffer for the housing. However, this solution has been rejected by the site planner because of access considerations for the residents of the East Somerville Neighborhood. Placing all of the retail and other facilities at the eastern end of the site makes a more attractive and accessible shopping area.

A technique of noise impact reduction which has been rejected in the Somerville case is the development of land in accordance with its compatible zoning classification; in this case, industrial. Development in accordance with a compatible use has proved impossible due to the site’s unmarketability for industrial uses and strong political pressure for residential development.

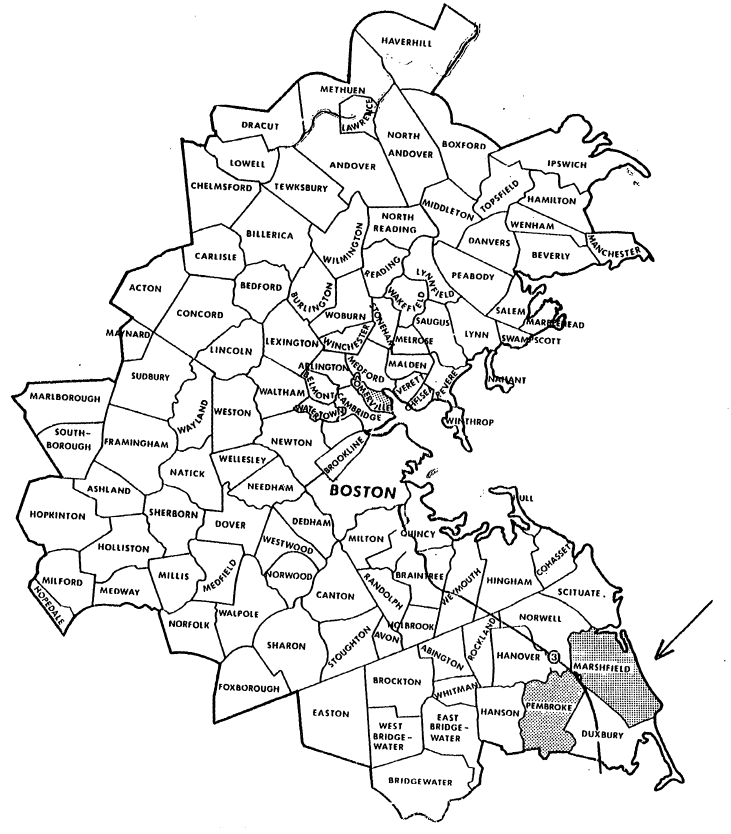

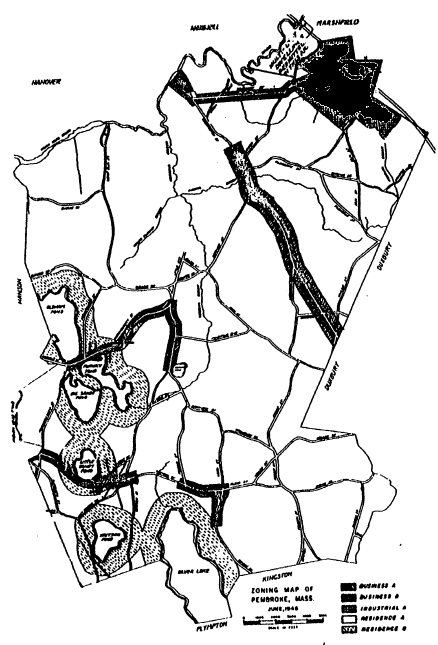

Marshfield and Pembroke are neighboring residential communities in rural southeastern Massachusetts. Because of highway access to both Boston and Cape Cod, the two communities have more than doubled their populations in the past decade. The residents are primarily middle income families. (See Figure A-11)

At present, the town governments are not especially concerned about highway noise. No regulation to control land use compatibility exists or is contemplated. However, if residential development proceeds at the present rate, the land along Route 3 may present a noise compatibility problem with which the two communities will have to deal.

The site chosen for consideration in this case study is a two-mile strip of primarily undeveloped land along Route 3. Because Route 3 runs along the borders of both towns at this point, part of the site belongs to Marshfield and part to Pembroke, involving both towns in the noise problem. The two towns took an initial step of zoning most of the land near the highway for industrial uses, but neither town has had much industrial development. If the need for residential development should arise, the use of this site may have to be rethought and residential development considered.

Both towns have town meeting forms of government. The legislative body is the Town Meeting, consisting of every registered voter in town. All town business, from approving the budget to zoning, is voted on by the Town Meeting. The benefits of this democratic form of government are inherent in the fact that anyone can have a voice in the town affairs if he attends the town meetings and votes. The disadvantages of this form of government are due to the fact that most townspeople do not attend the meeting unless they are particularly interested and/or affected by a particular article. In fact, it is often difficult to get the required five percent quorum at special town meetings concerning non-controversial matters. Thus, a town meeting can tend to become “packed” with those who have a special interest in a particular article and are therefore highly motivated to attend. It can accordingly become very difficult to pass, for example, a zoning change with the required % vote when it is opposed by a specially interested group.

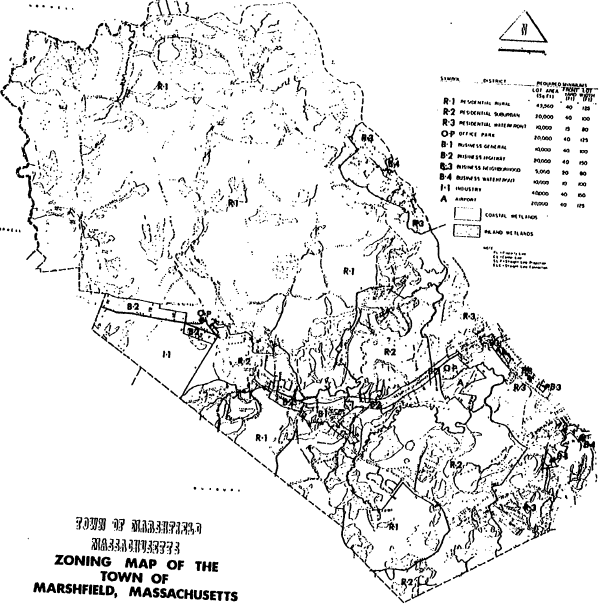

Both Marshfield and Pembroke have zoning bylaws which divide the towns into business, industrial, and residential districts. (See Figures A-12 and A-13) Development has been relatively light in both towns, with each being roughly 25% developed. Significant portions of the land in each town are classified as wetlands which severely restricts, and in some cases, prevents development. Most of the developed land is residential. Although both towns have been actively attempting to attract industry, much of the land zoned industrial remains vacant. Some commercial zones have been developed; however, this has resulted in an excess supply and there are a number of vacant stores and offices in these areas.

Most of the residential development has been single family lots, both because of the demand for this type of housing and the desire of the townspeople to prevent multi-family residential development. Marshfield’s opposition to multi-family housing began in 1968 when it was voted legal at the Town Meeting. What resulted was a rapid and extensive development of multi-family dwellings along Route 139, which the townspeople found to be unattractive and disruptive to the small-town atmosphere. By 1971, the town voted to prohibit any further multi-family residential development; and, with the present local attitude towards this type of development, it is unlikely that it will be allowed in the next 10-15 years. Pembroke’s zoning permits multi-family residences in a small portion of town, but most of the land so zoned is actually unbuildable due to state and local wetlands restrictions.

Noise Sources: The principal noise sources in the study are highway noise from Routes 3 and 139. Route 3 is a high speed, limited access highway with extensive automobile traffic and some trucks. Route 139 is a three-lane state road with numerous entry-ways. Considerable roadside development exists. A frequent source of local complaint is related to gravel trucks which travel west on Route 139 from gravel pits in Marshfield on their way to Boston on Route 3. The Route 139-3 interchange is also a source of noise because of accelerating and decelerating vehicles. There are no nearby major industrial or railroad noise sources. The local airport in Marshfield is restricted to non-jet operations, and it constitutes only a trivial noise source.

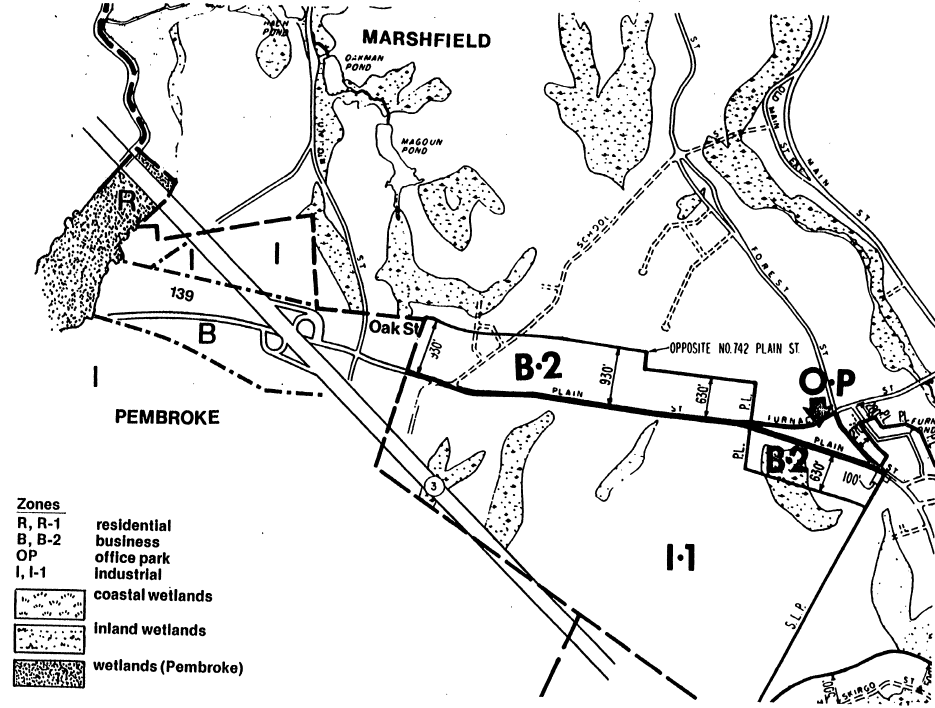

The Study Site: The study site is a two-mile strip of land along Route 3, which roughly follows the boundary of Marshfield and Pembroke. Route 139 intersects Route 3 midway along the site strip. (See Figure A-14)

The study site is mainly zoned industrial, except for the land along Route 139 and the interchange where it is commercial, and, in the extreme north, where it is residential. Development of the industrial zones in both towns has been very slow, with almost all of the land remaining vacant despite efforts to market it. There has been some construction of new homes in Marshfield in the site area, but this has been limited to one street with no homes within sight of the highway. Commercial development has been more extensive, with the land along Route 139 and the interchange more than 50% developed.

An interesting question raised by this case study is whether the industrially zoned land in either town can be developed as such in the foreseeable future. If it can, the concept of zoning the land for compatible uses only will have proven viable in this case. If, however, it cannot, pressure will eventually come from the landowners to rezone the land. Then, Marshfield and Pembroke will be faced with the task of finding another method to ensure noise compatibility. At present, there is some evidence that an industrial use of the area will not be marketable. While industrial development has been extensive for the past few decades along Boston’s Route 128 beltway, it has not made any significant progress along Route 3, despite efforts by the local industrial commissions to attract industry.

A commercial use of this area may also be unlikely. There is a major shopping plaza located five miles north of the site at a Route 3 exit. This, along with the current over-supply of retail space in Marshfield, casts doubt on the possibility of a shopping plaza at the case study site.

If, however, the residential growth of the two communities, and the surrounding area continues at its present rate, there may eventually be a demand for an industrial/research/office park or a shopping center in the site area.

While industrial development in the near future is not certain, residential development continues. In 1973, the consultant working on a master plan for the Marshfield Planning Board predicted that the town would reach 40,000 residents by 1990 despite downward changes in the birthrate and tighter zoning and subdivision laws in the town. At present, the town has room for roughly 25% more residential development.

Zoning for industrial use has been the only action taken that ensures noise compatibility; however, it should be emphasized that the issue of noise compatibility is one which simply has not been raised. This is primarily due to the fact that these two communities do not feel the threat of a noise compatibility problem. The area is sparsely populated and there is no real demand for residential development along the highway. In the case that some residential development does occur, the natural terrain and the original highway design combine to help considerably in the attenuation of highway noise transmitted to adjacent areas. Grade separation aids in the area north of Route 139 where Route 3 is first depressed in a cut designed to bring it down towards the valley of the North River and then elevated as it crosses the valley. South of Route 139 the elevation of Route 3 approximates that of the surrounding topography with small cuts and fills as necessary to compensate for the uneven surroundings. In this area, the land on both sides of the highway is heavily forested. Only if the land is rezoned residential and substantial development occurs will the noise become obvious.

Berms or Barriers: The view along Route 3 as one drives into the case study area is most pleasant, changing from cranberry bogs to woodlands. Just beyond Route 139 the long incline to the valley of the North River affords a spectacular view of the tidal river meandering through the salt marsh and of the low hills beyond. Any attempt to construct berms or barriers which would affect these scenic views would be politically unacceptable.

In Marshfield, for example, there is a Watershed Association, an Historical Commission, a Conservation Commission, an Historical Districts Committee and a Beautification Committee, all of whom could be concerned with the scenic and historic river. Any article on the town meeting warrant to require berms or barriers faces certain opposition from at least one of these groups.

Buffer Strips: If either town rezoned the industrial area to residential, a requirement for a buffer strip would be practical and easy to incorporate into the zoning bylaws. With 40,000 or 43,560 square-foot minimum lot sizes, rear lot depths of over 200 feet are to be expected even without the provision for a buffer strip. Requiring that a portion of the rear yard be a buffer with appropriate plantings provides no additional hardship.

Both towns presently require buffers on industrial lots between industrial uses and residential uses. Marshfield also requires buffers between business and residential uses and around cluster developments. This provision could be extended to highways in the zoning bylaw.

Site Planning – Subdivision: The terrain is sufficiently hilly to provide numerous low-noise pockets in the land near the highway. This, along with the large required lot size would make site plan layout to minimize noise incompatibility a very practical undertaking, if the presently zoned industrial land was rezoned residential. This is especially true for cluster subdivisions which are permitted in Marshfield.

There are several methods available in the existing laws of each town to incorporate acoustical site planning.

In Marshfield’s cluster zoning, site plans must be approved by the Appeals Board, an appointed body which is responsible for granting special permits, zoning variances, and cluster plan approval. If acoustical guidelines were included in the cluster provision of the bylaw, they would be considered by the Appeals Board. The Board could then reject a cluster subdivision plan if the guidelines were not met.

For conventional subdivisions, the procedure is slightly more complex. Marshfield’s zoning presently requires a certificate of occupancy which can’t be issued unless all provisions of the zoning bylaw and of the building code have been met. Thus, the Town Meeting could vote to amend either the zoning bylaw or the building code to prohibit construction of a residence in areas where the ambient noise level exceeded a certain specified level. The legality of such an amendment, under state law, would be subject to the approval of the state Attorney General, and would be subject to subsequent challenge in the courts.

Pembroke would have to incorporate the occupancy permit itself into its zoning bylaw before taking such noise related action.

A modification to the rules and regulations of the Planning Board could require acoustical site planning either on a definitive basis (such as specifying a maximum noise level in dBA) or by requiring, as part of subdivision submittal, a statement of noise compatibility measures being taken. These, too, would be subject to court challenge.

Site Planning – Individual Lots: Again, the uneven terrain and large required lot size make this method a practical possibility. Enforcement could follow the methods listed above, but would probably have to include some provision for exception where such site planning is impractical. Otherwise, the legality of such a regulation would be in doubt.

Height Limitations: A limitation of building height to a single story near the highway could be accomplished by use of a superimposed district. One problem with imposing height restrictions in this case is that it may be an unnecessarily stringent restriction. The large required lot size and the hilly terrain will in many cases make other measures such as limiting height unnecessary. Furthermore, such limitations might interfere with the panoramic view which would otherwise be available to homes near the North River. While special height restrictions might be incorporated into the zoning bylaw or building code of either town as one of a series of stated alternative choices available to the builder, the absolute requirement for such restricted height would be unrealistic and probably illegal.

Acoustical Architectural Design: Architectural building design in conjunction with site planning would be a practical method of utilizing the existing topography and vegetation to reduce noise impacts while still taking advantage of the scenic attributes of the area. Implementation of such a program of acoustical architectural design becomes, however, more a matter of incentive and education than enforcement.

One possible legal method of enforcement available to the two towns would be the inclusion of maximum permitted interior noise levels in the Board of Health’s regulations, the Building Code, or the Planning Board’s subdivision rules and regulations. Enforcement could be via the occupancy permit procedure which already exists in Marshfield’s zoning bylaw, or by a similar procedure which could be voted by Pembroke’s Town Meeting.

Design Services: Neither town has a professional design staff with the ability and time to provide acoustical guidance to individual builders. It is unlikely that the Town Meeting would decide to fund such a municipal service.

An Architectural Review Board could provide such a service. At present no such board exists in either town, and there has been little more than vague talk of founding one. However, each town has a large pool of potential members for such a board, and the towns could certainly benefit in many ways other than acoustical design if such boards were created What is needed is the key person to serve as catalyst towards the founding of an Architectural Review Board.

Acoustical Construction: The location of the study site is in an area of the country where temperatures rarely exceed 90 degrees and where proximity to the ocean and tidal marsh often results in cooling sea breezes. As such, air conditioning of residential homes is infrequent. Any building technique which calls for sealing windows and cooling with air-conditioning is therefore impractical.

1 State of California, California Administrative Code, Title 14, Div. 6, Chap. 3. City of Cerritos, California, Department of Administration, Environmental Impact Report Guidelines – Resolution, 73-20 (April, 1973).

2 City of Cerritos, California, General Plan, 1973, p. 11.04.

3 According to HUD’s criteria, “acceptable” noise levels are those which do not exceed 45 dBA for more than 30 minutes per 24 hours. HUD, Departmental Circular 1390.2, Noise Abatement and Control: Departmental Policy, Implementation Responsibilities, and Standards, p. 8.

4 This standard requires an L33 between 65 dB (A) and 75 dB (A). Ibid., p. 8.

5 This standard requires an L33 between 45 dB (A) and 65 dB (A), Ibid., p. 8.

6 It is assumed by the developer and the Somerville Planning Board that the noise levels from New Washington Street will be negligible. Therefore, no noise contours from New Washington Street are shown in figure A-10.