While the assessments evaluated pedestrian and bicycle safety needs at specific study locations, they also helped participants recognize common safety challenges and helped the different jurisdictions responsible for the assessment locations to work together to address these problems. Though this national effort was not a scientific study of pedestrian and bicycle safety needs across the country, the 52 locations, with many different contexts and settings, provided illustrations of issues that have been documented in many other reports and studies. Many of the issues identified in the assessments fall into two categories: physical barriers and institutional barriers related to policies and coordination.

Assessments from all States identified a wide range of physical barriers that prevent safe walking and bicycling. The problems ranged from facilities in significant disrepair to missing infrastructure and poorly designed roadways and signals. Common findings included a lack of safe and comfortable sidewalks, crossings, and bicycle facilities. Many roadways and signal systems were designed to accommodate high volume, high speed vehicular traffic, without considering the needs of all roadway users. The sections below discuss and show examples of some of the key issues related to roadway design, accessibility for all users, and bicycle safety concerns.

Creating safe and connected pedestrian and bicycle transportation networks is an area of increasing emphasis in communities throughout the country. Many roadway designs, whether constructed decades ago or quite recently, have prioritized driver comfort and safety over pedestrian and bicyclist comfort and safety. Observed characteristics of disconnected networks for non-motorists included:

Wide, multi-lane roads, without pedestrian facilities such as a median refuge or high-quality bicycle facilities, that contribute to high speeds and increase risk of exposure for non-motorized users;

Missing or poorly located curb cuts, making it difficult for people using mobility devices or strollers to cross safely at intersections;

Lack of marked crossings at intersections or midblock crossing locations on long blocks, leading to unpredictable and irregular pedestrian crossing behavior;

Gaps in sidewalks and bicycle facilities that create risk and limit ability for users to safely travel to and from destinations;

Constrained rights of way preventing construction and development of sidewalks or bike lanes;

Poor design of street parking, limiting visibility of and for pedestrians and bike riders;

Intersection designs that may not account for pedestrians and bike riders, making it difficult to cross; and

Roadways with an excessive number of driveways, creating many potential conflict points, and poor visibility.

These observations were key findings of many assessments, as the accompanying photographs show, and many assessments documented multiple designed-in impediments to safe cycling and walking.

The U.S. DOT is coordinating with key stakeholders and conducting research on best practices related to facility design, with new resources available at the FHWA Bicycle and Pedestrian Program webpage and the FHWA Office of Safety web page. FHWA also has many resources available to assist with applying a context sensitive approach(2) to roadway projects. FHWA partnered with the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) to develop resources on using a context sensitive approach to and Integration of Safety in the Project Development Process and Beyond. Most recently, FHWA proposed revisions to the 13 Controlling Design Criteria that would allow much more design flexibility on lower-speed roads on the National Highway System, without requiring special approval from FHWA.

The assessments addressed a range of challenges related to pedestrian safety, many of which also pointed to instances of infrastructure that were inadequate to meet the needs of people with disabilities. Challenges identified included:

Inadequate or missing curb ramps at intersections;

Long crossing distances combined with short crossing times at intersections;

Poorly maintained or missing sidewalks;

Poles, street furniture, or other obstructions impeding the path of travel;

Excessive grades and slopes, and

Inappropriate placement of pedestrian signal actuation buttons.

Poor maintenance practices contributed to the deterioration of both the physical and aesthetic condition of the infrastructure, often resulting in the accumulation of trash or other debris. Due to the seasonal timing of the assessments, the teams did not have an opportunity to observe the adequacy of ice and snow removal. However, the New Hampshire assessment team conducted a "pre-assessment" in the winter to look at conditions related to snow and ice. It found that overall, snow removal was done well, but there were issues with icy patches and the formation of ice dams.

In some cases, the problems were found with older infrastructure designed and built prior to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 or the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. In other cases the problems were present on more recent facilities, some of which had not yet been brought into ADA compliance but were included in local plans. These challenges highlighted the need for additional resources to maintain and manage existing assets, and for increased education and training for planners and engineers, to ensure that all new and upgraded facilities meet current standards in a timely fashion. In 2015, the FHWA Office of Civil Rights created a multi-office and disciplinary Working Group that works closely with the States to ensure that their ADA transition plans include the minimum regulatory required attributes. The new approach developed by the Working Group is focused on outcomes and on facilitating the acceleration of the States' ability to ensure ADA compliance in the public rights-of-way.

The assessment results highlighted a need for planners and engineers to coordinate with staff focused on ADA compliance, in order to more effectively work together to improve accessibility for all users. These responsibilities are often separated within an agency, sometimes resulting in missed opportunities for coordination. Every assessment noted the need for access improvements, and the great need to do more to involve communities of color and people with disabilities in pedestrian and bicycle safety assessments. The statutory definition of pedestrian includes persons with disabilities, which covers persons who use mobility devices as well as persons with vision or hearing disabilities. The first-hand experience and insight of persons with disabilities is invaluable to an assessment team. It is also vital to coordinate with ADA experts to ensure that assessments identify specific training and technical assistance needs related to accessibility, and with transportation planners to ensure that ADA solutions are woven into the transportation planning and project development processes.

It should be noted that while all of the assessments noted challenges related to accessibility, the assessments were not compliance reviews, and not meant to be used as an audit report of ADA issues. The assessments focused on deepening participants' understanding of and educating participants about barriers to safe walking and bicycling, and brainstorming ways to address existing and prevent such barriers in the future.

The U.S. DOT has resources that can be used to ensure that roadways are designed to be safe and comfortable for pedestrians, and accessible for all users. These resources include FHWA accessibility guidance and ADA resources, FHWA's Handbook on Designing Roadways for the Aging Population, FHWA's Guide for Maintaining Pedestrian Facilities for Enhanced Safety, and NHTSA's Walkability Checklist.

The National Aging and Disability Transportation Center (NADTC) is a new technical assistance center funded through a cooperative agreement with FTA. It provides access to resources (including this bus stop assessment toolkit and this assessment pocket guide to assist the disability community, seniors, human services providers, and the transportation industry in supporting accessible community transportation. This center builds on the history and activities of the previous technical assistance center for accessible transportation, called Easter Seals Project ACTION (ESPA). Resources currently available through ESPA's website will soon be available via the new NADTC website.

Many assessments discussed the need for dedicated bicycle facilities, whether as non-separated or separated bicycle lanes, as well as issues related to the design and maintenance of existing facilities.

In many cases, the assessment locations were on higher speed, higher volume roadways that would benefit from dedicated bicycling facilities to increase comfort and safety. On lower volume, rural roads, well maintained and paved shoulders with signs and striping may serve as appropriate pedestrian and bicycle facilities. The most appropriate type of bicycle facility depends on context (e.g., road function, size, speed and volume of vehicular traffic, volume of bicycling), and in some cases, participants suggested that bicycling facilities would be better placed on adjacent roads with lower speeds and traffic volumes. The Iowa assessment included a road that had recently undergone a road diet(3) from four to three lanes to accommodate a bicycle lane, and the assessment report noted the potential benefit of a "share the road" education campaign to teach people driving and riding bicycles how to operate safely together on the roadway. Using signing combined with education and enforcement campaigns to accompany new bicycling facilities may be helpful.

Several assessments noted concerns about bicycle safety at intersections, in particular regarding left turns. Whether in dedicated lanes or through travel lanes, bike riders often ride on the right side and merge left to turn. Merging across multiple lanes of traffic, especially on high speed roadways, or in steep topography with limited sight distance, can be difficult. Participants in the Montana assessment noted these concerns while making a left hand turn on a three-lane roadway, and suggested signing as a short term solution to increase driver awareness of people on bicycles.

Some assessments also found that bicycle lanes or wider shoulders designated for cycling were obstructed by debris or found drainage grates oriented with the long side parallel to the direction of traffic, which poses a risk that thin bicycle tires will get stuck in the grates. Such facilities need to be maintained and kept free of debris, and should also have bicycle-appropriate drainage systems.

The U.S. DOT has several resources that help identify bicycle safety concerns and appropriate solutions such as the NHTSA Bikeability Checklist, the FHWA Bicycle Safety Guide and Countermeasure Selection System. Most notable is the just-issued FHWA Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide, a comprehensive handbook for planning and discussing the appropriate placement and installation of this design innovation in U.S. cities.

In addition, FHWA is developing a Strategic Agenda for Pedestrian and Bicycle Transportation to establish a collaborative framework for pedestrian and bicycle planning, design, and research efforts in the next five years. The project will establish a unifying framework for addressing issues such as data collection and management; network implementation; research; and training and guidance. It will also identify critical gaps and near-term priorities for pedestrian and bicycling efforts. Implementation of the Strategic Agenda will involve coordinating policies, leveraging investments, promoting partnerships, and enhancing access to opportunity in communities and neighborhoods throughout the United States.

Since walking and biking are common, affordable and environmentally-friendly ways to reach public transportation, many of the assessments focused on, or included, an evaluation of safe bicycle and pedestrian access to bus stops and transit centers, as well as transit stations for light rail, subway, and commuter rail service.

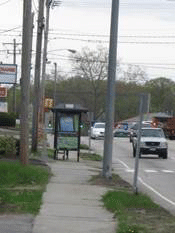

Many of the bus stops observed during assessments were located relatively far from marked crosswalks or intersections, leading to challenging conditions for pedestrians walking to or from destinations on the other side of the road - a crossing that is necessary on every round trip. On roadway stretches with long blocks and important destinations between intersections, midblock transit stops may be unavoidable, but they present a challenge because passengers will often cross the roadway to reach their destinations, regardless of whether there is a marked crossing. This is an area where transit agencies and roadway planners and engineers could coordinate to better consider transit stop placement, as well as ways to provide safe mid-block crossings.

In addition to bus stop placement, several assessments discussed issues with the infrastructure at and surrounding the stops. One assessment noted that the bus stop shelters, signs, and benches were generally in good condition, but sidewalk connections to the stops were in poor condition. Other assessments also found, that many bus stops are poorly lit, which can present visibility and personal safety issues.

For transit stations, many assessments noted that it is essential to plan, fund, design and build safe bicycle and pedestrian connections to the stations. One assessment around a transit station noted a previous study finding that approximately 20 percent of the cars parked in the 550 space parking lot were registered at addresses within one mile of the station, a distance that should be an easy walk or bicycle ride. These additional cars driving such a short distance exacerbate traffic management issues that affect the neighborhood and other pedestrians and bike riders trying to access the station. Pedestrians accessing that station must contend with a large parking lot without delineated pedestrian zones, sidewalks, or planted medians; and stairs that are unevenly distributed, slippery in the winter, and described as "tripping hazards" by transit riders. There were sidewalks located along the parking lot edges, but they did not have curb ramps, and were not well used because they did not lead to desired destinations. There is covered bicycle parking available at one entrance to the station, but no bicycle facilities on the roads leading to either station entrance, some of which include intersections with fast turning traffic. During the assessment, participants observed cyclists riding on the sidewalk rather than on the roadway, which while not prohibited in that area, could indicate that cyclists do not feel comfortable biking on the street.

Transit station area design that forces or encourages people to walk or ride through a parking lot or a bus bay to access the station entrance creates risky conflicts between vehicles, bicycles and pedestrians. The assessments also noted walls, viaducts and other barriers, which were built to safely separate non-motorized travelers from the rail right of way, unintentionally created poor sightlines, dim lighting, and an overall feeling of isolation, vulnerability and lack of personal safety.

Many assessment teams recommended specific improvements to address these conditions at bus stops and rail stations. For example, participants in the Arizona assessment suggested that infrastructure such as mid-block crossings, if designed and implemented appropriately, could help improve pedestrian safety around a planned light-rail extension.

Assessments recommended improvements to lighting, landscaping and sightlines, as well as pedestrian- and bicycle-oriented development, public art and signs. Project sponsors can engage people who travel by foot, bicycle, or mobility device in the planning and design phases of the station area, to ensure that their needs are identified and met.

For those transit stations that share right of way with freight, commuter rail and A Amtrak, the assessments identified and recommended safety improvements for highway-rail grade crossings, including adding DO NOT STOP ON TRACKS signs. One assessment suggested the "safety-critical design criteria" used for railroad grade crossings be employed as a model for assessing and planning for roadway risk around transit stops.

Participants who took part in assessments during peak commute times noted that station areas and surrounding infrastructure need to be able to support high pedestrian volumes traveling to and from transit stations and stops. Participants noted a need for wider sidewalks, pedestrian refuge, traffic calming and road diet measures to accommodate crowds, as well as creatively designed pedestrian crossings to ensure they are well used.

The U.S. DOT notes the availability of several resources that provide additional information to local jurisdictions looking to ensure that bus stops and transit stations have safe pedestrian and bicycle access, including the Mineta International Institute's report on Bicycling Access and Egress to Transit, the Transportation Research Board's Integration of Bicycles and Transit, the research report on Guidelines for Providing Access to Public Transportation Stations; and APTA Design of On-street Transit Stops and Access from Surrounding Areas. The FHWA report on Safety Effects of Marked versus Unmarked Crosswalks at Uncontrolled Locations: Final Report and Recommended Guidelines may help address crossing issues around midblock bus stops, and the FHWA-funded Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center website includes many resources on Access to Stations and Stops.

2 Context sensitive solutions (CSS) are collaborative, interdisciplinary approaches that involves all stakeholders in providing a transportation facility that fits its setting. It is an approach that leads to preserving and enhancing scenic, aesthetic, historic, community, and environmental resources, while improving or maintaining safety, mobility, and infrastructure conditions.

3 A Road Diet is generally described as removing travel lanes from a roadway and utilizing the space for other uses and travel modes. For more information see: https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/road_diets/info_guide/.