Section 350 of the National Highway System Designation Act of 1995 (NHS Act) (Public Law 104-59) authorized the U.S. Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT) to establish the State Infrastructure Bank (SIB) Pilot Program. A SIB is a revolving fund mechanism for financing a wide variety of highway and transit projects through loans and credit enhancement. SIBs are designed to complement traditional Federal-aid highway and transit grants by providing States increased flexibility for financing infrastructure investments. Under the initial SIB Pilot Program, ten states were authorized to establish SIBs. In 1996 Congress passed supplemental SIB legislation as part of the DOT Fiscal Year (FY) 1997 Appropriations Act that enabled additional qualified states to participate in the SIB pilot program. This legislation included a $150 million General Fund appropriation for SIB capitalization. The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21, Public Law 105-178, as amended by title IX of Public Law 105-206) extended the pilot program for four States: California, Florida, Missouri, and Rhode Island by allowing them to enter into cooperative agreements with the U.S. DOT to capitalize their banks with Federal-aid funds provided in FY 1998 through FY 2003.

Since the SIB Pilot Program was launched in 1996, steady progress has been made by States in advancing projects using the SIB financing mechanism. Operating within the limitations of State and Federal laws, States have been able to exercise a significant degree of latitude in the initiation and implementation of their programs, enabling the States to "customize" the focus of their SIB programs.

During the past five years, the SIBs have financed over 245 projects that have accomplished many of the original objectives of the pilot program, including project acceleration, economic development, and stimulation of private investment. Despite this success, states are at different levels in program implementation; some States have very active and mature programs and others have limited programs with moderate activity. In order to gauge how effectively the SIB pilot program is being implemented, the Federal-aid Financial Management Division of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), in partnership with FHWA Division Offices and State Department of Transportation offices (State DOT), performed a review of the SIB Pilot Program. This comprehensive review was conducted as a national financial management improvement project (FMIP), an element of FHWA's quality initiative.

This report documents the results of this review and is available on FHWA's Innovative Finance web site (www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovativefinance). FHWA hopes the results of this FMIP project will be of value in maximizing the benefits of the SIB financing mechanism and will contribute to long-term improvements in SIB operations.

This FMIP project recognizes the current and potential role that SIBs have as a financial tool to help meet transportation infrastructure needs as well as the benefits of sharing program implementation information and best practices. The primary objectives of the SIB review were to:

In meeting these objectives, the project was intended to provide State DOTs with comprehensive information that could be used to enhance their SIB operations and achieve a higher level of benefits over time. The information may also be useful to States who currently are not participating in the SIB pilot program, but who may have an opportunity to establish a SIB in the future.

A five-member team composed of financial staff from FHWA and the FTA conducted the review. The team gathered information from States through distribution of a questionnaire (see Appendix E) to FHWA division offices in every State with an active SIB. The questionnaire addressed a range of SIB operational elements, including organizational structure, financial policies and outreach efforts.

To supplement the questionnaires, team members visited ten State DOTs. Of the States visited, seven were among the ten original States selected by FHWA to participate in the SIB Pilot Program authorized by the NHS Act, (Arizona, Florida, Missouri, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, and Texas). The remaining three SIBs (Maine, Michigan and Pennsylvania) were approved subsequent to the 1997 U.S. DOT Appropriations Act, which expanded the SIB Pilot Program. During these visits, State officials and SIB administrators answered questions regarding administrative procedures, financial policies, future capitalization plans, and the types of changes they would like to see implemented in the future for their individual SIB programs. In addition to interviewing State officials and SIB administrators, the FHWA/FTA staff toured projects that received assistance from a SIB. In total, 32 States (including the 10 States with site visits) responded to the questionnaire. This report is based on the information collected from the questionnaire and the responses of the State officials participating in the site visits.

| SIB Benefits |

|---|

|

State Infrastructure Banks (SIBs) are intended to complement the traditional Federal-aid highway and transit programs by supporting certain projects with dedicated repayment streams that can be financed in whole or in part with loans, or that can benefit from the provision of credit enhancements. As loans are repaid, or the financial exposure implied by a credit enhancement expires, the SIB initial capital is replenished and can be used to support a new cycle of projects.

Under the provisions of the 1995 NHS Act, DOT was authorized to select up to 10 States to participate in the initial pilot program and to enter into cooperative agreements with FHWA and/or FTA for the capitalization of SIBs with a portion of their Federal-aid funds provided in Fiscal Years 1996 and 1997. The U.S. DOT Appropriations Act of 1997 opened SIB participation to all States and appropriated $150 million in Federal General Funds for SIB capitalization. In total, thirty-eight States plus the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico were selected to participate in the SIB pilot program. Of the 39 participants approved for the SIB program, 32 States (including Puerto Rico) have active SIBs. Four of the approved states have not participated due to the inability to pass state-enabling legislation and two states have de-obligated funds.

Two States in the TEA-21 pilot program (Florida and Missouri) have capitalized their SIBs with TEA-21 funds. Several important differences exist between the two pilot programs, including the percentage of Federal funds eligible for SIB capitalization, repayment provisions, the Federal outlay rate, and reporting requirements. More detailed explanations of the differences between the pilot programs are described in other FHWA publications.

SIBs have provided States significantly increased financing flexibility to meet transportation needs. The ability of SIBs to stretch both Federal and State dollars to increase transportation infrastructure investment has enabled projects to be built that may otherwise have been delayed or not funded due to budgetary constraints.

Although authorizing Federal legislation establishes basic requirements and the overall operating framework for a SIB, States have the flexibility to tailor the bank to meet State specific transportation needs. As of September 2001, 32 States (including Puerto Rico) have entered into 245 loan agreements with a dollar value of over $2.8 billion (See Appendix B, Table 3).

| SIB Loans Have Helped To: |

|---|

|

The results of the survey suggest that States have made major strides in implementing the SIB program and demonstrating its potential to increase transportation investment levels. Progress has been affected by the fact that the revolving fund concept was new to transportation financing and the start-up activities were complex. Also, TEA-21 impacted SIB program expansion by limiting additional Federal funding to only four States.

Most of the States responding to the survey have invested considerable resources in the establishment of their SIB program both in terms of funds contributed and time spent developing the program. These efforts have included passage of enabling State legislation, dedication of staff resources to the management of the SIB program, establishment of formal project selection procedures, and marketing and outreach initiatives. The majority of States needed State-enabling legislation to implement the SIB program. In some States, the lengthy legal processes for enacting legislation affected the implementation timeline.

Loans are the most popular form of SIB assistance. Lending funds permits loan repayments to be recycled for future funding of projects. Only two States (Minnesota and South Carolina) have leveraged their SIB program through the issuance of bonds, although nine States have the authority to issue bonds through the SIB. Puerto Rico leveraged its Federal and State SIB monies by funding a $15 million trust fund that was used as partial security for a $75 million bond issue.

SIBs use a variety of methods to set interest rates, repayment periods, and loan terms. Many States use a nationally recognized municipal index as a benchmark for establishing interest rates. Repayment periods range from the maximum 30-year term under the Federal SIB legislation to 10 years or less in some States.

States with the most active SIB programs share some key characteristics. These include strong program support from top State DOT officials, a formal application and selection process, favorable interest rates and flexible terms, extensive outreach and marketing, and expanded capitalization to meet demands. For example, Florida, a TEA-21 pilot State, conducted a statewide workshop as part of its outreach efforts which produced a better understanding of the SIB funding mechanism. Florida also built support for a State SIB with additional capitalization of $150 million in State General Funds.

The majority of States (23) identified a need for more Federal-aid highway program funds for SIB capitalization. This number includes four States desiring more access to Federal-aid highway program funds similar to those provided under the NHS Act and five desiring access to Federal-aid highway program funds similar to those provided under the TEA-21. Fourteen States did not specify a preference.

| Top Three State Requests for Future SIB Action |

|---|

|

Several of the SIB program administrators said they desired future legislative action by Congress to expand the SIB program. Legislative action could emulate previous formats, including special legislation (such as the NHS Act of 1995), annual appropriations acts (such as the 1997 DOT Appropriations Act), or surface transportation authorizing legislation (such as TEA-21).

States also suggested that FHWA provide more technical assistance and guidance to States concerning the administration of the SIB program. Several States said FHWA could play a greater role in sharing knowledge among States, publishing best practices reports, developing an integrated software package to manage cash flow and loan initiation and monitoring, and providing forums for learning from the experience of others.

Each SIB Program is unique because it must operate within the purview of both Federal and State legal environments. State legislation has affected the strategic direction of the SIB and in some States program parameters are more restrictive than in the Federal SIB program guidance. For this reason, the SIB team requested information concerning financial and program boundaries, in order to gauge the significance of these attributes upon program delivery.

Following the authorization of the SIB Pilot Program, some States were required by State law to pass legislation enabling them to participate in the program. The new State legislation varied significantly. Some States passed laws that were brief and general, leaving much of the implementation details to State administrators, while others passed very comprehensive legislation establishing oversight bodies and setting forth eligibility and selection criteria. A number of States established their SIB under pre-existing State law. For example, two States were able to implement their SIB programs under existing legislation originally written for a toll facility revolving loan fund. One State established a SIB program under an existing State law that allowed the creation of special purpose non-profit corporations.

| SIB Institutional Structures |

|---|

|

Legislation at the State level continues to evolve as SIB program managers identify ways of improving operations and pursuing additional capitalization. Eight States said they were either planning to seek legislative changes, or saw opportunities to improve the bank through legislative changes. Several States identified the lack of authority to issue bonds as a limiting factor and indicated that they would like to pursue legislative authorization to expand capitalization through bond financing. Also, several States indicated the need for special appropriations, through State legislative action, to increase SIB capital. One State initially used a pre-existing law to authorize the SIB, and then subsequently passed a new, SIB-specific law to broaden authority and enable future capitalization. This State has since contributed more State funding to the SIB, thereby enabling the State to provide additional project assistance.

Nine States responded that State legislation allows their SIB to issue bonds. Two of the nine States have issued bonds (Minnesota and South Carolina). In Arizona, although bonds are not authorized, the State has undertaken an innovative capitalization program selling notes of obligation to the State treasurer. Some SIBs are prohibited by State statute to enter into debt obligations.

States were asked to describe SIB program goals. Goals common to most States are project acceleration, attracting additional investment in projects (from local & private sources), economic development, and increased flexibility of funds.

States were about evenly divided between having formal administrative procedures and operating in an informal environment. In some of the more active States, several full-time or nearly full-time staff members are dedicated to administering the SIB. In other States, SIB responsibilities are assigned to existing State Department of Transportation financial, planning, or administrative professionals. Only ten states are charging administrative costs to the SIB.

Two-thirds of the SIBs have a Board or Advisory Committee comprised of members external to the State DOT, serving in an oversight role and having responsibility for project approval. In Arizona, a seven-member Advisory Committee, chaired by the ADOT Director, reviews loan applications and makes recommendations to the State Transportation Board, the final approval authority for project loans. Similarly, the Oregon Transportation Commission is the approving entity for SIB loans. South Carolina also has a seven-member Board approving loans with two members appointed by the Governor.

Although Federal law permits the SIBs to assist both highway and transit projects, nine States have limited their SIB assistance in the Federal Cooperative Agreement to highway projects. Loans are overwhelmingly the preferred form of assistance, although most states are authorized to provide other forms of credit assistance. The primary benefit of providing loans to projects (rather than grants) is that loan repayments are recycled for future generations of projects, thus furthering the development of transportation infrastructure.

SIB survey respondents were asked to provide information concerning their methods and policies for determining loan parameters, including interest rates, repayment periods, prepayment policies, payment deferrals and other financing techniques. Although SIBs are authorized to offer a variety of financial services, direct loans are the principal type of SIB credit activity. The financial terms offered to SIB applicants influence the level of SIB lending activity. SIB financing terms should provide a distinct advantage when compared with private lender rates and terms, otherwise applicants will prefer to use less expensive sources of capital. However, if the loan parameters fail to protect the capital of the SIB, the program could experience financial losses.

A critical component of each loan agreement involves establishing an appropriate interest rate. SIB managers may exercise their discretion in this area, provided that the SIB conforms to the Federal requirement to set rates at or below prevailing rates offered by the U.S. capital markets. Therefore, the various methodologies employed to establish a benchmark interest rate and a SIB loan interest rate varies from State to State.

Floating rates usually provide the strongest link to prevailing market conditions because the SIB repayment rate is reset periodically to a continuously changing rate. For example, the Virginia SIB uses floating rates that are equal to the earnings on an internal transportation trust fund. In contrast, fixed rates apply to the entire life of the loan.

A number of States are using indexed interest rates to capture current market trends by using a widely known and globally accepted interest rate or computed rate index as a proxy for the prevailing market rate. Examples of indexed interest rates include the use of the prime rate, municipal bond interest rate indices, expected rates of inflation or other widely recognized variables that reflect changing market conditions. SIB managers use the selected benchmark variable as a starting point to establish or to discount their loan rate. For example, the Colorado SIB uses the Merrill Lynch Bond Index rate for a seven to twelve year General Obligation Bond as published in the Wall Street Journal on the execution date of any given loan agreement. The Arizona SIB links their loan interest rate to Aa (Moody's Rating Scheme) rated municipal bond rates. Missouri develops interest rate recommendations based upon a comparison of both taxable and tax exempt securities. Alaska uses an inflation adjusted interest rate. Adjusting an interest rate to the rate of inflation ensures that the real interest rate remains constant. Six states use a municipal bond index in establishing their SIB loan interest rates.

Some fixed interest rate loans use a specific preset rate for all applicants regardless of market conditions or loan size. Michigan currently sets simple interest rates at four percent. Wisconsin and North Carolina use predetermined rates that coincide with the lending rate charged for other government infrastructure projects. Interest free loans are sometimes made to project sponsors faced with an emergency, financial hardship, or to advance projects of high priority.

Several SIBs use objective and subjective criteria to establish a specific interest rate within a target interest rate range. SIB lending policy in Pennsylvania permits emergency construction projects to receive a lower loan rate. Other objective criteria used in setting rates include the size of the requested loan amount or an accelerated repayment period. In addition, subjective criteria such as the degree of perceived financial or project risk, estimated strength of cash flows, or other repayment risk criteria may result in a lower interest rate.

The duration of the repayment period offers a way to control risk and to assist the financial feasibility of a project. Longer loan repayment periods represent a greater financial risk to the SIB and a diminished ability to assist future projects. Although repayment periods are within the purview of the SIB's administrative jurisdiction, Federal legislation stipulates a maximum repayment period not to exceed thirty years for SIBs authorized under the NHS Act, and no more than the lesser of either thirty-five years or the useful life of the project for SIBs authorized under TEA-21. Most SIB States have adopted the maximum Federal loan repayment period, although some States have established shorter time limits by legislative or administrative action. In Arizona, priority is given to loan applicants able to accept shorter repayment requirements of five years or less.

Other financial provisions govern SIB loan structures. Loan agreements may include prepayment, payment deferral or refinancing limitations. Some SIBs permit loan refinancing without prepayment penalties and may also permit payment deferrals in specific circumstances. Table 1 in Appendix B provides a comparison of different SIB loan parameters.

Nine of the states responding to the survey questionnaire indicated that matching contributions were required for SIB loans. Three states, while not requiring a match, encourage a match. Alaska's loan policy precludes the use of SIB money for 100% of the cost of the project, therefore, an implied match exists on all loan agreements.

Most States have not set maximum loan amounts because the level of available funds precludes large denomination loans; in effect, lending capacity constrains the maximum loan size. Several States have opted to enact minimum loan amounts. Missouri and Delaware specify a $5,000 and a $20,000 minimum loan amount respectively, in contrast to Arizona, which specifies a $250,000 minimum. Michigan sets a maximum loan amount of $2.5 million whereas Missouri sets a $25 million dollar maximum. North Carolina limits the maximum loan amount to the available State maintenance payments. Some SIBs have had to decline financial assistance to creditworthy projects due to limited lending capacity. For example, Wisconsin's SIB could not provide more than one million dollars of SIB assistance to an applicant seeking financing for a multimillion dollar project.

Some SIBs subsidize or provide below market loan rates. Arizona permits subsidies of up to 10% of the loan rate; Minnesota also offers loan subsidies. South Carolina subsidizes loan interest rates with State funds. The amount of the subsidy is determined on a project specific basis. Although subsidized interest rates represent a cost reduction to assisted projects, they will, over time, result in reduced growth of the SIB corpus and its ability to assist other projects. Therefore, it is important to determine appropriate, affordable interest rates for projects without sacrificing the SIB's long-term viability.

Repayment structures vary within and among the individual infrastructure banks. The South Carolina SIB structures loan repayments in amounts that vary from a single lump sum payment to quarterly payments over a twenty-year period. Many States have established annual repayment cycles for direct loans. Annual repayment schedules afford administrative simplicity, but may not reveal borrower financial difficulties in a timely fashion.

The majority of responses indicated that most SIBs do not provide technical assistance to potential applicants. SIBs providing applicant support focus on fundamental business expertise. New Mexico and Ohio provide financial expertise and Nebraska provides accounting support. Oregon provides comparative financial estimates. Virginia provides operating, administrative and accounting services. Washington assists loan recipients with the preparation of annual reports. Wisconsin provides cost-benefit analysis assistance.

In implementing the SIB program, States have had the flexibility to determine the best approach to project selection, given each State's unique SIB structure and the long-term goals of their program. The first step in the application process involves the solicitation of projects for loan consideration. Seventeen SIBs employ a formal application process that utilizes specific forms or instructions for applicants. These forms request the borrower to document information pertaining to repayment issues and project eligibility. Application cycles vary among the SIBs and may occur periodically throughout the year, continuously, or on an ad hoc basis determined by funding availability and applicant interest. Some SIBs dispense with formal applications because all available funds are exclusively loaned internally to the State. In some States, projects requiring additional funding are selected from the State Transportation Improvement Program.

Several States have developed an on-line application process through an internet site as part of streamlining applicant processing efforts. Some States have established pre-screening procedures to ensure that general eligibility guidelines are met. These pre-screening efforts help to reduce application review loads. Typically, following initial screening decisions, eligible projects are evaluated using specific evaluation criteria.

Six SIBs charge application fees, loan origination fees or both. New York charges a $1,000 flat fee, while Ohio charges a 1/4 % fee throughout the life of an existing loan. Vermont charges a $500 application fee, plus a 2% commission fee at closing. Missouri charges a minimum $250 fee or 0.15% of the loan amount, up to a maximum of $1500.

An important consideration in the implementation of the SIB program is the ability to leverage scarce Federal funds with other funding mechanisms, a key objective of the SIB program. This is important not only because of the benefit of attracting additional investment, but also because the presence of additional capital contributions by the project sponsor may reduce the default risk of the SIB loan. Loan application procedures offer an opportunity for the SIB to review the financial commitments of other parties to the construction project.

The variety of methods used by SIBs to select loan recipients from among a pool of loan applications reflects the level of competition for SIB funds and individual SIB policy. Some SIBs use a "first-come, first served" policy, provided that an applicant meets all minimum eligibility requirements. Some SIBs do not use any selection criteria beyond existing legal boundaries. Fourteen SIBs differentiate applicants by using a combination of objective and subjective criteria involving financial considerations and program objectives.

| Best Practice Florida's Project Selection Criteria |

|---|

|

Project selection frequently employs some form of risk assessment. SIB practices in this area range from moderate effort to comprehensive due diligence reviews. In some of the larger, more active SIB programs, managers typically use criteria similar to those used in municipal underwriting such as security provisions/ covenants, coverage, review of the borrower's financial reports, and examination of revenue streams. Sometimes a borrower's credit rating can be used as a proxy for SIB loan risk assessment. Credit risk may not be a significant factor when loans are repaid with Federal or State funds. Most States have the ability to intercept aid to borrowers if they default on a loan, and this intercept provision makes default situations less likely. Several SIBs rely upon external resources to assist with risk analysis. South Carolina, Virginia, Missouri, and Ohio use financial advisors and Vermont taps the State Economic Development Authority.

Key criteria used for selecting and approving projects for SIB assistance fall primarily into two categories: (1) mandatory or threshold criteria. Is the project eligible for Title 23 (may be used only to provide assistance to construction of Federal-aid highways), or Title 49? (may be used only to provide assistance with respect to capital projects) and (2) ranking or discretionary criteria (Does the project fit within the State's goals and priorities?). All States use the first category for selecting projects because this is a requirement of Federal legislation. Following initial screening based on threshold criteria, eligible projects may be subjected to more detailed project selection criteria, including the alignment of the project with State goals and priorities, ability to repay the loan and overall financial strength, and extent of project acceleration. State requirements may include planning process documentation, design specifications, and identification of a repayment revenue stream.

A variety of methods may be used to rank loan applications, including weighted averages and subjective and objective analysis. States may rank loan applicants according to criteria unique to each SIB program. These criteria may strive to accomplish specific transportation goals such as economic and public benefit. Some States derive formal application ratings by using numerical methodologies to calculate application scores. These methods use weighted and/or unweighted criteria (Colorado, South Carolina, Arizona).

SIB assistance has been used for all eligible phases of project development from planning and designs to construction. A SIB loan for part of or all of the pre-construction phase (often the phase that is least likely to receive financing from another source and where project revenues have not yet been realized) could make the difference in determining the project's financial feasibility. Some SIB programs limit assistance to funding construction costs, or other activities that more directly advance project completion. To date, SIB assistance has been provided to a range of recipients, including State DOTs, local and tribal governments, metropolitan planning organizations, cities, counties, transit authorities, and the private sector.

SIBs have established different administrative processes for loan approvals. Many SIBs use commissions, committees or review boards to select recipients, whereas other SIBs present recommendations to a single individual for approval. Nineteen SIBs use a standardized agreement to complete and document the terms of each loan. Two additional SIBs modify standard agreements by integrating individualized or negotiated terms into a loan agreement template.

In implementing the financial framework of the SIB program, States had the availability of business support services within the State government, enabling them to access cost effective program assistance and business expertise. Accounting practices and cash investment policy among the SIBs demonstrate a significant reliance upon existing State financial management systems.

Most SIBs have been set up with an umbrella account in the State DOT's accounting system. Within this account, SIBs are generally split into Federal highway and transit sub-accounts, reflecting the requirement in the NHS Act. Another common feature is to have separate accounts for Federal and State capitalization funds. State accounts within the SIB generally contain the State's required capitalization match for Federal funds. This account can also be used to deposit additional State capital. However, it must be remembered that State capitalization required for matching Federal funds is considered Federalized and all Federal requirements apply to these funds. To ensure that Federal requirements do not apply to State funds over and above the State matching capitalization, some States have established sub-accounts for their State funds so that commingling of funds is avoided. States have also established a separate account for loan repayments, or several accounts for repayments from different sources (e.g., Federal and non-Federal). Sub-accounts have also been established for interest earnings. Typically, cash balances are invested by the State Treasurer's office in accordance with State investment policies. Interest earnings are credited to the SIB as required by the Federal legislation.

SIBs employ a diverse selection of financial management software. One third of the States use existing State software to manage their SIB accounts, or have modified existing software to accommodate SIB loan calculations such as amortization schedules. Some States use multiple software packages to manage different program elements. Commercially available software packages used by the SIBs include:

SIB surveys indicated a need to identify commercial software applications that would best accommodate reporting and banking requirements.

In most states, cash investment policy for the SIB is the responsibility of the State Treasurer or State Controller, reflecting State law or policy. The role of the SIB manager is to coordinate investments, but not take an active role in the formulation of State cash investment policy. A notable exception to this is Missouri's SIB which was organized as a not-for-profit entity. An independent board has responsibility for investment of SIB cash. The board may invest funds in certificates of deposit in six possible banks, with a restriction of no more than 25 percent invested in any one bank. In addition, the board operates within specific investment guidelines that define risk and quality standards for selected investment instruments.

More than 80 percent of the SIBs are able to intercept State transportation funds if a borrower delays loan repayments. Missouri does not intercept State aid, but includes a provision in loan agreements with project sponsors that any "pass-through" Federal funds can be used to repay SIB loans. The ability to ensure loan repayment by imposing financial offsets reduces loan default risk. SIBs that lend to organizations that do not receive government aid may negotiate specific terms that address repayment contingencies.

More than half of the SIBs prepare monthly management reports; quarterly reports represent the second most common reporting frequency. Some SIBs provide daily activity reports in addition to periodic reports. Four States prepare internal management reports on an annual basis, and one State provides a management report on an ad hoc basis. Internal reporting frequency is correlated to SIB lending activity levels; large loan portfolios increase the necessity of more frequent monitoring.

Among the survey respondents, only two States, Arizona and Wyoming, require their SIB to maintain a minimum balance. The remaining responses indicated that the SIB either did not have a requirement or had not implemented a cash balance policy. Although a minimum balance is not a legal obligation, Arizona requires a $20 million dollar minimum balance that reflects the sizable activity of its program and the extent of its financial commitments. In contrast, the Wyoming SIB policy simply states that sufficient capital must be available to meet awarded contract payments.

More than 70 percent of the survey responses indicated that the SIB did not have a reserve requirement policy. Among the States with a reserve requirement, Missouri credits one percent of the loan amount to loan loss reserves, and Oregon charges a one percent reserve fee for each loan. Wisconsin sets a reserve requirement based on the outstanding balance and interest rate of the loan, and Vermont has a reserve requirement based on the value of the loan collateral and the borrower's financial health.

SIBs are generally reviewed as a part of the single audit process for recipients of Federal funds. Some SIBs use private accounting firms to perform the annual audits while others, are audited by the State auditor. Several States are conducting internal reviews or hiring consultants to find ways to improve the SIB.

Survey responses indicate a broad spectrum of SIB marketing activities ranging from highly visible and carefully planned campaigns characterized by numerous contacts, published materials and mail solicitations to a complete absence of any program marketing. Eleven SIBs do not market their programs; this group includes two SIBs that have suspended their marketing initiatives because of insufficient capital available for loans.

Some SIB programs use State DOT personnel to assist with marketing activities. Missouri depends on ten district offices to describe the program to interested parties, and Texas disseminates program information via a network of twenty-five district offices and twenty-five metropolitan planning organizations.

Predictably, most SIB marketing efforts focus on traditional channels for transportation projects, including government programs and offices such as metropolitan planning organizations, city, county or other local government offices. States with more active marketing and outreach programs also target organizations and groups outside of government or the transportation industry. These groups include consultants, bankers, chambers of commerce, engineering societies and other organizations concerned with economic development activities. These unusual venues have resulted in successful loan applicants. For example, a SIB loan recipient in Ohio was informed about the SIB program via a business consulting organization's newsletter.

Twelve SIBs have developed Internet sites. Some SIBs have developed Internet sites deployed within an existing State DOT web site rather than maintaining their own server. SIB web site materials include application forms, program guides, descriptions of approved projects, contact information and news items. The low cost of a web site, combined with universal access and the ability to share a significant volume of information make a web presence an attractive marketing venue for the SIB program.

Nine SIBs rely upon some type of presentation, conference or visit to market their SIBs, while eight SIBs market via brochures, five use newsletters, five use workshops, and two have conducted mailings. Other marketing techniques include the use of press releases, program guides, marketing plans or professional networking. Many States have used multiple forms of these methods.

Several SIBs have adopted creative outreach methods. Oregon solicits potential applicants by researching news stories citing transportation funding gaps and then contacts local project managers with information about the SIB program. In Ohio, as an incentive for project sponsors and to put capital to use, the SIB offered lower than normal interest rates for a period of time and marketed the discounted loans to borrowers.

In addition to the State-level marketing efforts, Federal marketing of the SIB program has included conference presentations, newsletters, an Internet site devoted to innovative finance initiatives, and several publications about the SIB program.

SIB loans have financed a diverse array of transportation projects including vehicle and ferryboat purchases, parking facilities, multimodal centers, railroads and airport construction. While more than twenty States are able to offer SIB loans to transit projects, only seven have transit loans. As of September 30, 2001, approximately $25 million of Federal contributions to the SIB program have supported public transportation loans. Despite this achievement, a smaller percentage of public transportation projects received SIB assistance compared to other forms of surface transportation projects. Several legal and program obstacles may account for the diminished lending level in this particular transportation sector.

A SIB must enter into an agreement with the Federal Transit Administration to commence transit lending. Among the States with the legal authority to lend to transit projects, two declined to commit capital to a designated transit account. Transit projects must satisfy a relatively more extensive set of Federal regulations, making SIB loans to transit projects a more complex endeavor.

SIB managers indicated that they were not actively pursuing options to develop a more active transit lending level and to solicit more transit projects. Some SIBs do not closely coordinate their outreach activities with transit agencies, and as the sponsoring agency, a transit authority is expected to propose a project and initiate an application. Although one SIB lacked a close relationship with the local transit authority, SIB managers said that they would welcome transit applications.

Identifying suitable projects with a loan repayment source was also cited as a deterrent to developing transit projects. Nevertheless, certain transit enhancements such as bus shelters could claim a unique and dedicated repayment source such as advertising revenue. For example, in Pennsylvania, a loan for an historic preservation of a railroad station combining many transportation modes including local bus transportation will be repaid with revenue generated by station tenants and concessionaires.

In general, the more active SIBs share some common characteristics. Strong program support by high-level officials within the State DOT is considered to be a critical success factor. Top management leadership can build a broad base of support for the SIB, both externally and internally. This leadership was often essential in gaining the support needed to pass enabling legislation. Further, the internal recognition and interest in the SIB program expressed by management serves to validate its role and importance as a financing tool.

Internal support and coordination within the State DOT is also a factor contributing to successful SIB implementation. A coordinated implementation effort among planners, financial managers, and engineers has proven to be of particular significance in bringing about a better understanding of the associated benefits of the SIB mechanism.

An effective marketing program can enhance program implementation and have a positive impact on the level of SIB activity. Outreach through brochures and mailings, workshops, meetings with external stakeholders and potential loan applicants, and targeted presentations are among the special activities undertaken in States with more active SIBs as part of their marketing efforts.

Successful experiences in implementing other non-grant financing approaches, such as privatization and revolving loan programs, provided a certain knowledge base to facilitate SIB start-up activities and operations. In other words, applying "lessons learned" was beneficial to program initiation activities. Finally, access to existing State resources and expertise provided additional resources for the SIB, further facilitating program implementation. States sometimes borrowed talent from existing programs and were supplied critical support in areas such as accounting, information systems or legal matters.

The level of SIB loan activity differs among SIBs and in large part is linked to capitalization factors. In some of the more active States, State contributions to the SIB have been above the required match or additional Federal funds were made available through TEA-21. A larger capital base then supports a more diverse loan portfolio and can contribute to greater financial stability, accelerating the transition to a true revolving loan fund. The following chart demonstrates the impact of increased capitalization as well as leveraging through bonding on SIB loan activity. Six states account for over 90 percent of SIB loan activity through September 2001. Of the six States, South Carolina's bank is highly leveraged based on amounts loaned through bonding; three States, Ohio, Arizona, Florida, have all contributed additional State funds to their respective banks; and Missouri has benefited from additional TEA-21 capitalization.

| State | Number of Agreements |

Loan Agreement Amount (thous.) |

Disbursements to Date (thous.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Carolina | 5 | 1,502,289 | 510,428 |

| Florida | 32 | 465,000 | 94,000 |

| Arizona | 23 | 373,192 | 156,850 |

| Ohio | 35 | 146,624 | 102,550 |

| Texas | 32 | 88,900 | 70,016 |

| Missouri | 10 | 69,251 | 66,754 |

| Subtotal | 137 | $2,645,256 | $1,000,598 |

| Other States | 108 | 245,931 | 179,358 |

| Total | 245 | $2,891,187 | $1,179,956 |

In States with less active SIBs (one or two loans), loans were generally made to an account within the State DOT, and were interest free. These States also contributed only enough State capital to match Federal funds.

Several States indicated that certain obstacles or challenges have slowed progress in implementing SIB programs. Many States lack the legislative authority to leverage their funds and thereby increase the capitalization level of the SIB. Capitalization levels constrain the SIB maximum loan size and loan portfolio. Additional Federal and State capitalization funds could alleviate these limitations. The complexity of Federal requirements was cited as an obstacle to SIB activity and the effectiveness of the program, particularly for transit projects. Several project sponsors noted that Federal requirements for smaller projects can significantly delay construction schedules and increase overall project costs. A few States noted that insufficient demand for loans was a factor affecting program implementation. However, the lack of interest or demand in some instances may be attributed to limited marketing efforts.

| Leveraging SIBs |

|---|

|

The following examples of State programs demonstrate the flexibility and diversity possible in structuring SIBs to best meet State needs:

The SIB review has revealed considerable information, insights, and suggestions for future action to enhance SIB operations. Further, the interviews have provided a perspective on the challenges States encountered in implementing the SIB and on developing strategies for the future. The consensus among the States interviewed during the SIB review was that the SIB financing mechanism is an effective tool, but there are opportunities to improve its effectiveness.

Many States indicated that initiating and managing a revolving loan program was more complicated than first anticipated and suggested more Federal assistance in this area. It is expected that SIB program activity will continue to increase, as States gain experience in program delivery, although the pace of activity will be impacted by capitalization levels.

Although some SIBs may attain a sufficient capital level to sustain and expand operations, SIBs that cannot access additional resources are likely to experience program stagnation. The more active SIB States today have increased the capitalization of their banks by issuing bonds or committing additional State funds.

Based on the SIB review, the following recommendations are provided to enhance SIB effectiveness:

Establishment of the SIB Pilot Program under the provisions of the NHS Act represented a major milestone in the evolution of innovative financing approaches for surface transportation. Since the program was launched in 1996, States have made notable progress in advancing projects through this tool, despite limited capitalization funds and the curtailment of the program in TEA-21. In a number of States the SIB is proving to be a highly effective funding approach, particularly where State funds have supplemented Federal capitalization.

Contemporary evidence suggests that the SIB program is serving its intended niche and demonstrates the value that this financing mechanism is bringing to States that have an active and mature program. However, the SIB program is not reaching its full potential due to several factors identified in this report. Insufficient capitalization, lack of State enabling legislation, and limited marketing activities are among the factors affecting the pace of SIB implementation.

States continue to show a strong interest in the SIB program and support for continuing the program in transportation reauthorization legislation as a standard element of the Federal-aid highway and transit programs. Several States indicated in the survey that loan demand exceeds available resources. Also, a number of States not included in the initial pilot program have expressed an interest in program participation should the program be offered to all States in future legislation.

The Federal Highway Administration hopes this report will be of value to States as they strive to enhance their SIB programs and maximize the benefits of the SIB as a tool to stretch limited transportation dollars, and accelerate the building of needed surface transportation improvements. By sharing lessons learned and enhancing communication, successful implementation strategies can be developed.

FHWA and FTA will continue to provide technical assistance to States as they look to improve or enhance their SIB programs. Both agencies will expand their SIB outreach and education efforts through the Innovative Finance Quarterly publication, the Innovative Finance website, workshops, and conferences.

The SIB Review Team extends special thanks and appreciation to the State DOTs participating in the SIB survey for their time, cooperation, and sharing of experiences. Thanks are also extended to the FHWA Division Offices for their support and assistance.

For additional information on the SIB program, please contact the FHWA Federal-aid Financial Management Division at 202-366-0673 or the FTA Office of Policy at 202-366-4050.

Bridge Replacement Project in Independence, Oregon

The town of Independence, Oregon borrowed $650,000 from the Oregon Transportation Infrastructure Bank to replace a weight-restricted bridge that was on a primary access route to a local school. Weight restrictions meant that school buses, too heavy to cross the bridge, had to drive miles out of their way to cross a more modern bridge to get to the school.

The Oregon Transportation Infrastructure Bank worked with the town and came to an agreement on terms for a loan. The town would use its portion of Highway Bridge Repair and Replacement funds and some of its portion of the State gas tax to repay the loan.

Conway Bypass in Conway, South Carolina

SC 22, originally called the Conway Bypass, is a new 28.5 mile, fully controlled access highway linking US 501 between Conway and Aynor to US 17 near Briarcliffe Acres (between Myrtle Beach and North Myrtle Beach).

This new highway was designed to help alleviate congestion on US 501,

a main route into Myrtle Beach, and provide a new route to one of the nation's

most popular resort destinations.

The project was a result of a partnership made up of

SCDOT, the Federal Highway Administration, Horry County, the State Infrastructure

Bank and Fluor Daniel. The highway's construction time - just three years - and innovative financing methods have made it a model for other transportation

departments across the country.

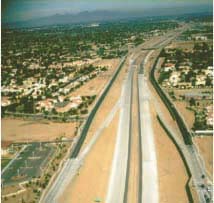

Price Corridor Segments in Chandler, Arizona

A $26 million short-term SIB loan accelerated construction of this new 2.7 mile, six lane freeway segment by one year. The Warner to Fry segment of the Price Freeway, part of the Maricopa Freeway System, was identified by the City of Chandler, Arizona as a critical project, given the major industrial and commercial development along the corridor. The advancement of this project improved mobility for the area and generated economic benefits. Without the financial assistance of the Arizona SIB, this advancement would not have been feasible.

Chandler is financially participating in the project by sharing in the interest costs on the SIB loan. The project also attracted private sector capital with a major developer paying a portion of the City's interest payments. The project was completed in December 2000.

Highway 179 Segments in Cole County, Missouri

The project (approx. 4.9 miles) consists of acquiring right of way and constructing an extension of Highway 179, including an interchange and an outer road on Highway 54, from Highway 50 to Route B in Jefferson City and Cole County. The segment also includes a grade separation bridge over Route 54 connecting Idlewood Road and Southwood Hills Drive removing the at-grade intersection at Route 54. The Highway 179 Transportation Corporation in Jefferson City is the borrower of a $6 million SIB loan.

| State | Fixed Interest Rates | Deferrals Allowed | Refinancing Permitted | No Prepayment Penalties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | X | X | X | |

| Arizona | X | X | X | |

| Arkansas | ||||

| Colorado | X | |||

| Delaware | X | |||

| Florida | X | |||

| Iowa | X | X | ||

| Indiana | X | |||

| Maine | X | X | X | |

| Michigan | X | X | X | X |

| Missouri | X | X | X | |

| Nebraska | X | |||

| New Mexico | X | |||

| New York | X | X | X | |

| North Carolina | X | X | ||

| North Dakota | X | |||

| Ohio | X | X | ||

| Oregon | X | |||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | |

| Rhode Island | X | X | ||

| South Carolina | X | X | ||

| South Dakota | X | |||

| Tennessee | X | |||

| Texas | X | X | ||

| Vermont | X | X | X | |

| Virginia | X | |||

| Washington | X | X | ||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | |

| Wyoming | X | X |

| State | Publications | Mailings/News Releases | Conferences/ Workshops | Calls/Meetings with Stakeholders | Internet Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | X | ||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X |

| Colorado | X | X | X | ||

| Delaware | X | ||||

| Florida | X | X | X | ||

| Iowa | X | X | |||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | |

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | |

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | |

| New Mexico | X | ||||

| Ohio | X | X | |||

| Oregon | X | X | X | ||

| Pennsylvania | X | ||||

| South Carolina | X | ||||

| Texas | X | X | |||

| Vermont | X | X | |||

| Virginia | X | ||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X |

| State | Number of Agreements |

Loan Agreement Amount ($000) | Disbursements To DateI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alaska | 1 | 2,737 | 2,737 |

| 2 | Arizona | 23 | 373,192 | 156,850 |

| 3 | Arkansas | 1 | 31 | 31 |

| 4 | Colorado | 2 | 400 | 400 |

| 5 | Delaware | 1 | 6,000 | 6,000 |

| 6 | Florida | 32 | 465,000 | 94,000 |

| 7 | Indiana | 1 | 3,000 | 0 |

| 8 | Iowa | 1 | 739 | 739 |

| 9 | Maine | 23 | 1,780 | 759 |

| 10 | Michigan | 23 | 17,034 | 13,033 |

| 11 | Minnesota | 7 | 66,124 | 29,581 |

| 12 | Missouri | 10 | 69,251 | 66,754 |

| 13 | Nebraska | 1 | 1,500 | 0 |

| 14 | New Mexico | 1 | 541 | 541 |

| 15 | New York | 2 | 12,000 | 12,000 |

| 16 | North Carolina | 1 | 1,575 | 1,575 |

| 17 | North Carolina | 2 | 3,565 | 1,565 |

| 18 | Ohio | 35 | 146,624 | 102,550 |

| 19 | Oregon | 9 | 11,483 | 11,181 |

| 20 | Pennsylvania | 15 | 14,600 | 14,600 |

| 21 | Puerto Rico | 1 | 15,000 | 15,000 |

| 22 | Rhode Island | 1 | 1,311 | 1,311 |

| 23 | South Carolina | 5 | 1,502,289 | 510,428 |

| 24 | South Dakota | 1 | 11,740 | 11,740 |

| 25 | Tennessee | 1 | 1,875 | 1,875 |

| 26 | Texas | 32 | 88,900 | 70,016 |

| 27 | Utah | 1 | 2,888 | 2,888 |

| 28 | Vermont | 3 | 1,030 | 0 |

| 29 | Virginia | 1 | 18,000 | 18,000 |

| 30 | Washington | 1 | 700 | 0 |

| 31 | Wisconsin | 2 | 1,188 | 1,188 |

| 32 | Wyoming | 5 | 49,090 | 32,614 |

| 245 | 2,891,187 | 1,179,956 | ||

| State | Name | Title | Telephone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | Roxanne Bash | Fed Planning Program Manager | roxanne_bash@dot.state.ak.us | (907) 465-6982 |

| Arizona | John Fink | Finance Administrator | jfink@dot.state.us.az | (602) 712-8023 |

| Arkansas | Scott E. Bennett | Assistant Division Head-Program & Contracts | Scott.Bennett@ahtd.state.us | (501) 569-2262 |

| California | Barbara Lewis | State Highway Account Loan Program Manager | Barbara_Lewis@dot.ca.gov | (916) 324-7623 |

| Colorado | Will Ware | Budget Analyst | will.ware@dot.state.co.us | (303) 757-9061 |

| Delaware | Diane Dillman | Transportation Trust Fund Administrator | ddillman@mail.dot.state.de.us | (302) 739-2693 |

| Florida | Gene Branagan | Project Financial Team Manager | gene.branagan@dot.state.fl.us | (850) 414-4421 |

| Maine | Terry Caswell | SIB Coordinator | Terry.caswell@state.me.us | (207) 287-2641 |

| Iowa | Joan Rost | Financial Manager (FHWA) | joan.rost@fhwa.dot.gov | (515) 233-7303 |

| Indiana | Christopher Kubki | Economist | ckubik@indot.state.in.us | (317) 232-5640 |

| Michigan | Kris Wisnieski | SIB Coordinator | wisniewski@mdot.state.mi.us | (517) 335-2614 |

| Minnesota | Brad Larsen | State Program Administrator | brad.larsen@dot.state.mn.us | (651) 282-2170 |

| Missouri | Patty Purves | Financial Manager | purvep@mail.modot.state.mo.us | (573) 526-2412 |

| Nebraska | Steve Maraman | Budget & Finance Manager | smaraman@dor.state.ne.us | (402) 479-3646 |

| New Mexico | Robert Olcott | Chief Economist | Robert.olcott@nmshtd.state.us | (505) 827-5522 |

| New York | Carlton N. Boorn | Director of Accounting Bureau | oboorn@gw.dot.state.ny.us | (518) 457-2424 |

| North Carolina | Danny Rogers | Program Analysis Unit Head | drogers@dot.state.nc.us | (919) 733-5616 |

| North Dakota | Tim Horner | Director of Transportation Program Services | Thorner@state.nd.us | (701) 328-4406 |

| Ohio | Melinda Lawrence | Administrative Assistant | Mlawrence@odot.dot.ohio.gov | (614) 644-7255 |

| Oklahoma | Mike Patterson | Assistant Director of Finance | mpatterson@odot.org | (405) 521-2591 |

| Oregon | Paul Cormier | Transportation Bank Officer | Paul.o.cormier@odot.state.or.us | (503) 986-3922 |

| Pennsylvania | Jim Smedley | Transportation Planning Manager | smedley@dot.state.pa.us | (717) 772-1772 |

| Rhode Island | Brian Peterson | Chief Financial Officer | bpeters@dot.state.ri.us | (401) 222-6590 |

| South Carolina | Debra White | Comptroller, SC DOT | whitedr@dot.state.sc.us | (803) 737-1243 |

| South Dakota | Chuck Fergen | Financial Analyst | Chuck.Fergen@state.sd.us | (605) 773-4114 |

| Tennessee | Laurie Clark | Fiscal Director | Lclark@mail.state.tn.us | (615) 741-8988 |

| Texas | Dorn Smith | Budget, & Finance Division | Dmith1@dot.state.tx.us | (512) 463-8721 |

| Vermont | Thomas A. Daniel | Financial Manager | Tom.daniel@fhwa.dot.gov | (802) 828-4423 |

| Virginia | Chandra M. Shrestha | Project Finance Manager | shrest2a_cm@vdot.state.va.us | (804) 786-9847 |

| Washington | Nancy L. Huntley | Project Funding Analyst | huntley@wsdot.wa.gov | (360) 705-7378 |

| Wisconsin | Dennis Leong | Chief, Economic Development/Planning | leong.dennis@dot.state.wi.us | (608) 266-9910 |

| Wyoming | Kevin Hibbard | Budget Officer | Khibba@state.wy.us | (307) 777-4026 |

| States Completing Questionnaires: | States Visited | |

|---|---|---|

| Alaska | North Carolina | Arizona |

| Arkansas | North Dakota | Florida |

| California | Oklahoma | Maine |

| Colorado | Rhode Island | Michigan |

| Delaware | South Dakota | Missouri |

| Iowa | Tennessee | Ohio |

| Indiana | Vermont | Oregon |

| Minnesota | Virginia | Pennsylvania |

| Nebraska | Washington | South Carolina |

| New Mexico | Wyoming | Texas |

| New York | ||

Florida

https://www.fdot.gov/comptroller/PFO/sib.shtm

Michigan

https://www.michigan.gov/mdot/0,4616,7-151-9621_17216-22406--,00.html

Minnesota

http://www.dot.state.mn.us/planning/program/trlf.html

Ohio

http://www.dot.state.oh.us/Divisions/Finance/Pages/StateInfrastructureBank.aspx

Oregon

https://www.oregon.gov/odot/about/pages/financial-information.aspx

Texas

https://www.txdot.gov/government/programs/sib.html

Vermont

http://www.veda.org/financing-options/other-financing-option/state-infrastructure-bank-program/

Report to Congress: Evaluation of the U.S. Department of Transportation State Infrastructure Bank Pilot Program, 2/28/1997.

Innovative Finance Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 1, Winter 2000, SIB Update: DOTs Opt for Increased State Capitalization of SIB

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovativefinance

http://www.innovativefinance.org/ (website discontinued)

In the following questions, please identify the approving/establishing authority as appropriate, (e.g., who decides what interest rate to assign a project loan.)

| 1. | How are loan rates and terms determined? | ||

| 2. | Have you established maximum loan terms? If yes, describe. | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 3. | Are loan rates subsidized? | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 4. | Are payment deferrals allowed? | ||

| 5. | Are refinancings permitted? | ||

| 6. | Do prepayment provisions involve penalties? | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 7. | Are there matching requirements for loans? | ||

| 8. | Are there minimum/maximum loan amounts? | ||

| 9. | What repayment structures have been established (monthly, semiannual, or yearly)? | ||

| 10. | Are other forms of financial assistance available to applicants, such as financial expertise, accounting, annual report preparation, etc? | ||

| 1. | Have you established a formal application and selection process for the award of SIB financial assistance? If yes, briefly describe the process in the space provided (or attach application/selection documents). | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 2. | How frequently are project applications solicited? | ||

| 3. | How is credit risk assessed? | ||

| 4. | How is credit risk assessed? | ||

| 5. | What selection criteria have been established to evaluate projects? Have any minimum threshold criteria been established? Are weights assigned to the criteria? | ||

| 6. | What is the project selection ratio? (i.e., number of acceptances/number of applications) | ||

| 7. | What types of projects are eligible for financial assistance? Are any types of projects or phases of projects ineligible for assistance? | ||

| 8. | Is there a minimum project cost to be eligible for SIB assistance? | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 9. | Have you implemented standard loan agreements? | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 10. | Describe application fees, if any. | ||

| 1. | Please describe the accounting structure for your SIB Program. What internal controls have been established? | ||

| 2. | Does State law or SIB policy prescribe any minimum balance to be maintained in the SIB? If yes, what is the minimum balance? | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 3. | In the event of borrower default, does the State have authority to intercept distributions of State revenues to the government borrower? | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 4. | What financial and/or accounting software is used by the SIB? Was new software developed or was existing software modified? | ||

| 5. | What types of financial reports have been developed to monitor the financial status of the SIB? How frequently are financial reports issued (daily, monthly, quarterly, or annually)? | ||

| 6. | Is an annual financial audit conducted? By whom? | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

| 7. | Describe the cash investment policy. | ||

| 8. | What financial management improvements are planned, if any? | ||

| 9. | What types of Federal assistance could better assist the SIB with its operations or policies? | ||

| How does the State market or promote the SIB (e.g., brochures, workshops)? What kinds of groups has the State tried to reach (local governments, non-profit or private entities) | ||

| Do you have or plan to have a SIB web site? What is it? | [ ] Yes | [ ] No |

Name: ______________________________

Title: ________________________________

Agency: _____________________________

Phone: ______________________________

Fax: ________________________________

E-mail: ______________________________

Date: _______________________________