On July 17, 2014, the President announced the Build America Investment Initiative, a government-wide effort to increase infrastructure investment and economic growth by engaging with state and local governments and private sector investors to encourage collaboration, expand the market for public-private partnerships (P3s) and put Federal credit programs to greater use. As part of that effort, the Presidential Memorandum tasked the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) to establish the Build America Transportation Investment Center (BATIC), a one-stop-shop for state and local governments, public and private developers and investors seeking to utilize innovative financing and P3s to deliver transportation projects. USDOT has made significant progress in its work to expand access to USDOT credit programs, spread innovation through tools that build capacity across the country, and deliver project-focused technical assistance to help high-impact projects develop plans, navigate Federal programs and requirements, and evaluate and pursue financing opportunities. This includes an effort to provide a range of technical assistance tools to project sponsors, including a series of model contract provisions for popular P3 project types. Development of these tools fulfills a requirement under The Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) that directs DOT and FHWA to develop public-private partnership (P3) transaction model contracts for the most popular type of P3s for transportation projects. Based on public input favoring an educational, rather than prescriptive, contract model, FHWA is publishing a series of guides describing terms and conditions typically adopted in P3 concession agreements.

This guide presents key concepts for the structuring and development of legal contracts for Availability Payment-based highway public-private partnerships (P3s). It is part of a broader effort by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) to promote understanding of P3 transactions, which includes the Core Toll Concessions P3 Model Contract Guide, found at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/p3/toolkit/publications/model_contract_guides/core_toll_concession_0814/. This guide is designed to provide industry-standard concepts, relevant common tools and mechanisms, and situational examples applicable to Availability Payment-based P3 transactions, and follows a structure similar to the previously published guide on toll concessions.

A glossary of terms is included as Appendix A to assist in understanding the terminology used in this guide. Certain terms used throughout this guide are capitalized and defined in Appendix A in the same manner as if used in a contract. Other terms that reflect concepts common to the P3 market are not capitalized in the guide but are explained briefly in Appendix A. Where example provisions have been provided, certain terms that would normally appear capitalized in a contract may be capitalized and set in square brackets; however, definitions for such terms are not provided in Appendix A and readers of this guide should consult with their legal advisors prior to implementing the example provisions in any contract.

A P3 describes a contractual arrangement between a Department (public authority) and a Developer (private entity) in connection with the design, construction, financing, operation and maintenance of an asset that will be used by or is otherwise valuable to the public. Unlike conventional methods of contracting for new construction (e.g., design-build), in which discrete functions are divided and procured through separate solicitations, P3 transactions contemplate a single private entity (generally a consortium of private companies comprising the Developer) which is responsible and financially liable for performing all or a significant number of the Project functions, including design, construction, financing, operation and maintenance. In recent years, Departments, including transportation agencies, have turned to P3 transactions to procure new transportation facilities, including highway projects, in an attempt to obtain time savings, cost savings, and more innovative, higher quality Projects with reduced risks. In exchange, the Developer receives the opportunity to earn a financial return commensurate with the risks it has assumed either through the receipt of Toll Revenues (on which the Developer takes both demand risk and toll collection revenue risk) or Availability Payments (on which the Developer takes financial risk associated with performing the Work according to agreed performance metrics) on such terms as may be outlined under the Concession Agreement. This guide focuses on the terms and issues relevant to transactions for which the Developer is compensated through periodic payments (Availability Payments) based on the performance of the Project against agreed performance metrics. P3 transactions based on a toll concession mechanism are the subject of a separate guide published by the FHWA.

Availability Payments are made, subject to appropriation, by the Department to the Developer in exchange for the continuous delivery of the Project in accordance with the performance requirements set forth in the Concession Agreement. The Concession Agreement will set a maximum payment that may be earned if the Project is available at all times and meets all requirements, and will also specify a regime of deductions that may be assessed if there are periods of Unavailability or failures to meet the performance requirements. The Availability Payment is typically paid monthly in arrears based on the Developer's performance, subject to any deductions for Unavailability or failure to perform.

The contractual agreement between the Department and the Developer, generally known as the Concession Agreement, lies at the heart of the P3 transaction structure. Traditionally, important contractual terms related to P3 transactions have included the following:

Because the Concession Agreement dictates the essential short and long-term dynamics of the P3 transaction, it is critical to the long-term success of the Project that the Department and the Developer can develop contracts that effectively exercise the intentions and priorities of the public sector.

P3 transactions are being undertaken with increasing frequency in order to deliver complex highway projects in the United States. They represent an option for State and local governments to procure the development, financing, construction, operation and maintenance of transportation facilities. The value to the Department in a P3 transaction is the transfer of costs and subsequent risk related to the design, build, financing, operations and/or maintenance of the Project to the Developer. In return the Developer is rewarded via an agreed-upon compensation (e.g., Toll Revenues or Availability Payments for services performed) for a prescribed term. Whether a P3 transaction provides value to the Department and ultimately the public is to be assessed on a case-by-case-basis. Through this guide, the FHWA seeks to create a better understanding of P3 market terms and possible contract structures for use in the consideration and development of Availability Payment-based P3 transactions.

The development of this guide stems from section 1534 of the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21). The MAP-21 requires the development of standard model contracts for the most common types of P3 transactions, with a view to encouraging transportation agencies and other officials to use these model contracts as a base template for use in P3 transactions.

In meeting these requirements, FHWA has already taken several actions prior to the publication of this guide. An initial "listening session" for the public and stakeholders was held in January, 2013. The FHWA received a total of 28 comments following this listening session, and these comments were taken into account when selecting the topics to be covered in this guide. In addition, on September 10, 2014 the FHWA published in the Federal Register a final version of the first part (the "Core") of the Toll Concession Model P-3 Contract Guide and on January 16, 2015 a draft version of the second part (the "Addendum") of the Guide, requesting comments from interested parties.

The focus of this guide is on P3 transactions that involve long-term concessions for designing, building, financing, operating, and maintaining highway projects. This document complements other primers, guides and tools the FHWA Center for Innovative Finance Support (formerly Innovative Program Delivery) has developed on the topic of P3s, including the primer, Establishing a Public-Private Partnership Program; documents on conducting evaluation of P3 proposals, including risk assessment, value for money analysis, and financial assessment; and the suite of educational tools known as P3-VALUE.

Based on public and stakeholder input from the listening session, the FHWA ascertained that a set of prescriptive, standardized contracts for use in P3 transactions would not be acceptable or desirable to all State DOTs and other public agencies in the United States that are interested in using P3 for highway projects. As such, it is the objective of the FHWA that this guide will assist in educating public agencies and stakeholders on key issues in highway projects procured as P3 transactions, the trade-offs, and ways to provide protections to the traveling public and State and local governments while continuing to attract private investment. Using the knowledge base of highway projects previously undertaken as P3 transactions, this guide attempts to educate agencies and stakeholders that may be only beginning to approach P3 transactions, while still providing relevant information to more sophisticated and experienced State and local transportation agencies. Overall objectives include the following:

This guide provides specific analysis for State and local transportation agency personnel on the following topics related to highway projects procured as P3 transactions using an Availability Payment concession:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Topics include the background to the development of this Guide, an overview of its intended purpose and suggested approaches for utilizing its contents.

Chapter 2: Completion Testing and Performance Security

Topics include the achievement of substantial completion as a project milestone, the effect of late completion on the Project, approaches to the determination of the occurrence of substantial completion, the Department's liability following substantial completion, and topics related to Construction Performance Security.

Chapter 3: Availability Requirements

Topics include the meaning of "Availability" and "Unavailability" in an Availability Payment P3, and a discussion of Availability and service requirements during the various stages of the Term.

Chapter 4: Maintenance and Handback Requirements

Topics include Handback Requirements, Handback Inspections, and the establishment of reserve accounts, letters of credit, and payments related to Handback.

Chapter 5: Payment Mechanism and Financial Model Adjustments

Topics include the payment mechanism typically used in Concession Agreements, including discussion of Milestone Payments, Unavailability Adjustments, penalties and deductions to Availability Payments, and Availability Payment funding. Other topics discussed include the definition and handling of the financial model, and changes made to the financial model to respond to certain events during the Term.

Chapter 6: Insurance

Topics include the background and incorporation of insurance requirements applicable to the Developer in the Concession Agreement, as well as benchmarking of insurance premiums, uninsurable risks, and conditions under which insurance is regarded as unavailable under the Concession Agreement.

Chapter 7: Contract Term and Nature of The Proprietary Interest

Topics include the various considerations relevant to setting the Term, as well as the nature of the Developer's proprietary interest in the Project and considerations relevant to determining the type of interest to grant.

Chapter 8: Supervening Events

Topics include a definition of Supervening Events, the types of contractual relief generally granted in Supervening Events, and the role of insurance in mitigating supervening risks.

Chapter 9: Change in Law

Topics include the concerns of parties, unforeseeable changes in law and relevant considerations, tax-related issues, and compensation that may result from changes in law.

Chapter 10: Department and Developer Changes

Topics include the right of the Department to require changes in the Work, the procedures for compensating the Developer, and the right of the Developer to propose changes.

Chapter 11: Assignment and Changes in Equity Interests

Topics include the restrictions on the right of the Department and the Developer to assign their interests in the Concession Agreement, as well as the definition of a change in ownership, example contractual provisions related to a change in ownership, permitted and prohibited changes, and participant concerns.

Chapter 12: Defaults, Early Termination, and Termination Compensation

Topics include events related to default by the Developer and the Department, cure periods, and termination rights of both parties in the event of a default, as well as all issues related to compensation for Early Termination.

Chapter 13: Indemnities

Topics include indemnities that the Developer may be required to agree to in favor of the Department and a general discussion of the indemnification procedures that the Concession Agreement may discuss.

Chapter 14: Federal Requirements

Topics include Federal law requirements imposed on the Developer when the Project receives Federal funding assistance.

Chapter 15: Amendments to Key Developer Documents

Topics include the background behind and general approaches taken in response to the conflicting desires of the Developer to maintain flexibility to amend project documents and the Department to receive the Project it bargained for when it approved the Developer's project documents at the outset.

Chapter 16: Lender Rights and Direct Agreement

Topics include the separate Direct Agreement between the Department and the Lenders, which principally contains administrative acknowledgement by the Department of the Lenders' interest in the project, the Lenders' rights to take action in the event of a Developer Default, and the Department's agreement not to terminate the Concession Agreement until the Lenders are afforded an opportunity to cure such default.

Chapter 17: Department Step-In

Topics include the events triggering the Department's right to step-in, the effect of a Department step-in on the Developer's obligations, and the effect of a Department step-in on the Department's other rights.

Chapter 18: Disputes

Topics include a discussion of the Dispute Resolution Procedures often used in Concession Agreements.

Chapter 19: Intellectual Property

Topics include the ownership and licensing of intellectual property necessary to carry out the obligations under the Concession Agreement, and the intellectual property rights upon the expiry or termination of the Concession Agreement that may be necessary for the Department to operate the Project.

Chapter 20: General Provisions

Topics include the application of, and consideration to be given to, general provisions that are typically standard and not heavily negotiated.

The FHWA encourages States, transportation agencies, and other public entities to use this guide as a resource when developing their own Concession Agreements.

Educational Reference

The suggested primary purpose of this guide is as an educational tool for State and local agencies and is not intended to be used as legal advice. Each chapter contains high level introductions to key topics, example definitions and provisions as well as guidance on contract structuring in respect of those key topics.

This guide is designed to be an informational tool for State and local governments to refer to when considering a P3. Every Project is unique and attention will need to be given to the specific factors relevant to each transaction. This guide introduces and analyzes several areas that have generally required significant consideration in highway projects structured as P3 transactions in the United States to date. Each such P3 transaction may require consideration of more or fewer factors than those covered herein. This guide is for informational purposes only. Transportation agencies are encouraged to retain or utilize their own counsel and other appropriate external expert advisors in any P3 transaction.

Illustrative and Example-Based

Existing Projects and Concession Agreements have informed the structure of this guide. Furthermore, market-standard provisions have been discerned and analyzed for the benefit of the reader. The goal of these inclusions is to provide real-life examples of the theoretical analysis presented in the guide. They also provide State and local agencies with a broader perspective and understanding of the P3 market and several non-contractual dynamics that may play a significant role in P3 transactions. The example provisions, when taken together with the explanations and descriptions of key issues, provide insight into best practices and may be utilized to develop solutions that can protect the interests of State and local governments, tax-payers and the traveling public. The inclusion of specific example provisions that may be derived from particular Projects does not indicate a recommendation or promotion of one particular form of P3 transaction over another. Instead, the examples illustrate a technique, mechanism, or dynamic that the FHWA views as valuable for the purposes of educating State and local agencies. Every P3 transaction is different, and what is applicable for one transaction may not be applicable for another transaction.

Glossary of Terms and Example Provision Definitions

A glossary of terms has been provided to assist in understanding the guide. The terms are for informational purposes only and are not designed to be used in legal documentation, even though a number of the terms may also be used in example provisions found in this guide. The example provisions contained throughout this guide include bracketed capitalized terms. These terms are commonly used in the industry but both the terminology and substantive meaning of these terms will differ from transaction to transaction. Therefore, use of these terms (and the technical legal definitions that will accompany them in the Concession Agreement) should be considered carefully for each P3 transaction. As noted above, the descriptions contained in the glossary of terms do not represent legal definitions of these bracketed capitalized terms.

This guide is intended to contribute to a better understanding of P3s and considerations for structuring a highway project procured as a P3 transaction. The FHWA has designed the guide to be as effective as possible in supporting public agencies in their exploration and implementation of successful P3 transactions, in the aim of promoting better and more efficient highway projects.

Substantial Completion is a critical Project milestone. Substantial Completion, which signals that the Project is functionally complete and available for use, typically occurs upon the satisfaction of specified conditions (see Section 2.3 below for a discussion on typical conditions and the process for verifying their satisfaction). Those specified conditions are designed to measure whether the Project is functionally complete and, save for some minor remaining Work (commonly referred to as "punch list" Work), ready to commence service to the traveling public.

Once Substantial Completion occurs, the Developer will be able to earn Availability Payments in accordance with the Concession Agreement. The Developer must thereafter make the Project available to the public during the times specified in the Concession Agreement and must operate and maintain the Project in accordance with the minimum performance requirements. Failure to do so will result in deductions to the Availability Payments (see Chapter 5 (Payment Mechanism, Performance Monitoring and Financial Model Adjustments)). Because the occurrence of Substantial Completion also commences operations and maintenance, the conditions to Substantial Completion will typically include the satisfaction of operations and maintenance-related obligations (such as the procurement of insurance for the operations and maintenance period) in addition to traditional obligations relating to the completion of construction work.

In addition to Availability Payments, the Department may also provide a lump sum payment to the Developer upon the occurrence of Substantial Completion. The Department may make such a payment if the Department is prepared to contribute funding to the Project, though it is not required and not all Departments will be able or willing to do so. The Developer will often use such a payment to repay debt raised to finance construction costs, or to pay the construction contractor - the allocation will be determined by the Developer as part of its plan of finance for the Project and prospective Developers will seek to make the most efficient use of the funds in light of their individual approach to funding the Project. See Chapter 5 (Payment Mechanism, Performance Monitoring and Financial Model Adjustments) for a full discussion of such payments.

The occurrence of Substantial Completion will typically mark the end of the construction phase of the Project and the beginning of the operating phase. A number of State rules and regulations applicable to traditional design and construction contracts will cease to apply to the Project at this time, including certain regulations applicable to disadvantaged business enterprises and local sourcing requirements, however the requirements of each jurisdiction are unique and their applicability to individual Projects may vary, so Departments should consult with their legal advisors regarding the application of such requirements to their specific circumstances.

The Concession Agreement will specify the date by which the Developer must achieve Substantial Completion of the Project, which will be taken from the schedule in the Developer's bid for the Project. This Guaranteed Substantial Completion Date will not be changed due to delays in construction unless a Supervening Event (see Chapter 8 (Supervening Events)) occurs for which the Developer is expressly entitled to an extension of time .

The Developer's debt service obligations will be structured based on the original schedule, often with some contingency built in to accommodate minor delays. As a result, the Developer's debt service obligations may come due at a time when the Developer is not earning Availability Payments.

In many traditional design and construction contracts, and in some toll concession contracts, the Department will assess daily liquidated damages against the Developer for failing to achieve Substantial Completion by the Guaranteed Substantial Completion Date. The amount of liquidated damages is specified in the contract and calculated as a reasonable estimate of the Department's losses resulting from late delivery of the Project. In an Availability Payment transaction, however, liquidated damages are typically not assessed. The Availability Payments measure the value to the Department of receiving a completed, open road that meets all performance specifications, and because the Availability Payments are not made until the Project is completed, the Department does not suffer a loss which may be compensated. In many States, assessing liquidated damages in the absence of a genuine loss constitutes an unenforceable penalty.

In addition, many Concession Agreements contain a Long Stop Date by which the Developer must achieve Substantial Completion or else be in default. The Long Stop Date is typically set by the Department as one year after the Developer's Guaranteed Substantial Completion Date, but could be longer or shorter depending on the complexity of the Project and the expected construction schedule. Although the Developer will be at risk for the financial consequences of late completion, Concession Agreements typically contain this Developer Default because the Department will not wait indefinitely in light of the public interest in receiving a completed Project. The Developer thus has a period in which to manage late completion and the resulting financial consequences, but once the Long Stop Date is reached, the Department has the right to take action, including terminating the Concession Agreement and replacing the Developer (see Chapter 12 (Defaults, Early Termination, and Termination Compensation).

Set forth below is an example of a typical definition of the Guaranteed Substantial Completion Date and the Long Stop Date:

Guaranteed Substantial Completion Date means January 1, 2015.

Long Stop Date means the date which is 1 year after the [Substantial Completion Date].

Substantial Completion Date means the date on which each of the conditions to [Substantial Completion] set forth in [Section [X]] of the [Concession Agreement] shall have been satisfied.

While the Developer is typically focused on avoiding the consequences of late completion, Departments may wish to consider the potential consequences of early completion of a Project. If a Project achieves Substantial Completion earlier than expected, the Department will be required to begin making Availability Payments earlier than expected as well. The Department's budget and planning process may, however, constrain its funding and prevent it from making Availability Payments before a certain date. The Concession Agreement may therefore state that irrespective of whether Substantial Completion has occurred, the Developer will not be entitled to receive Availability Payments before a fixed date. See Chapter 7 (Contract Term and Nature of the Proprietary Interest) for a discussion of the impact of early completion on the Term.

The occurrence of Substantial Completion is a significant financial event in the life of a Project, and all parties involved will take an interest in the process for determining whether it has occurred. The Department will want to ensure there is a robust testing regime in place to verify that the Project has been completed satisfactorily before any payments are made, while the Developer and Lenders will want to ensure that the testing regime is administered objectively and is based on factors within the Developer's control.

Concession Agreements typically contain a fixed list of conditions to Substantial Completion, focusing on completion of the design and construction work, completion of all requirements for operations and maintenance work, the placement of insurance for operations, performance testing of any equipment or software that will be used to operate the road, and others as may be appropriate depending on the unique conditions of the Project.1

The list of conditions will not typically include an open-ended obligation that the Developer "satisfy all other reasonable requirements of the Department", as this will be viewed by Lenders as a significant risk to the achievement of Substantial Completion and payment by the Department. The list should therefore include all matters that the Department believes are relevant to determining Substantial Completion. In addition, Lenders will typically require that the Department has must issue a certification once the conditions are objectively met. This is a key issue because Lenders may be concerned that Departments with too much discretion will insist on additional or different standards than originally agreed in the Concession Agreement, thereby putting in jeopardy the source of funding for repayment of the Project Debt. Lenders therefore prefer an objective test, subject to dispute resolution in the event of a disagreement over whether the test has been met.

Also, the list of conditions will not typically include tasks performed by third parties outside of the Developer's control, unless the Concession Agreement separately includes parameters for managing delays resulting from non-performance by such third parties (i.e., if a Compensation Event is provided by the Department). In some cases, the Developer may agree to accept the risk of third party performance if the third party's willingness and ability to perform on schedule are sufficiently reliable. Each Project will be unique in this regard and should be evaluated on a case by case basis, though in general Lenders will demand contingencies when these risks are introduced.

Set forth below is an example of a typical list of conditions to Substantial Completion that does not include any Project-specific requirements:

The [Department] will promptly issue a written certificate that the [Developer] has achieved [Substantial Completion] upon satisfaction of all of the following conditions for the [Project]:

(a) the [Developer] has completed the [Design Work] and [Construction Work] in accordance with the [Project Documents] (including, without limitation, installation and commissioning of all [Project] equipment and systems required to be installed and commissioned by [Developer]);

(b) all certifications for the [Final Design Documents], independent design check of the [Final Design Documents], all mechanical, electrical and electronics systems, and bridge inspection and load rating reports have been submitted;

(c) all lanes of traffic as set forth in the design documents are in their final configuration and the [Developer] has certified that such lanes have been constructed in accordance with the requirements of the [Project Documents] and are available for continuous use by traffic subject only to [Permitted Closures] or [Closures] necessary for [Planned Maintenance];

(d) certification that the [Developer] has received, and paid all associated fees due and owing for, all applicable [Governmental Approvals] required for the operation and maintenance of the [Project], and there exists no uncured violation of the terms and conditions of any such [Governmental Approval] (except to the extent contested in good faith);

(e) the [Developer] has prepared, in consultation with the [Department], and submitted the [Punch List] in accordance with the procedures and schedules set forth in the [Project Management Plan] and there remains no [Construction Work] to be completed other than the [Construction Work] described in the definition of ["Punch List"];

(f) all plans, manuals and reports for the [O&M Work] to be performed during the [O&M Period] have been submitted and, if applicable, approved by the [Department] as required under the [Project Documents];

(g) all [Insurance Policies] required by the [Concession Agreement] for the [O&M Work] have been obtained and are in full force and effect, and the [Developer] has delivered to the [Department] verification of insurance coverage as required by the [Concession Agreement]; and

(h) the [Developer] has certified that it has completed necessary training of personnel that will be performing the [O&M Work] and has provided the [Department] with copies of training records and course completion certificates issued to each of the relevant personnel.

To the extent the Department is concerned that the technical elements of a Project are too complex to rely on generic criteria or the Dispute Resolution Procedures, an alternative approach is to utilize the services of an expert Independent Engineer hired to review the completed Project against a set of technical standards and determine, objectively and independently, whether they have been met. The Independent Engineer may be hired by the Developer or jointly by the Developer and the Department (the precise approach may depend on procurement requirements applicable to the Department), but will in either case have a legal duty of care to both parties. This approach is used regularly in international markets, particularly for complex Projects that require significant performance testing, and is typically acceptable to Lenders.

One of the most important ways that a P3 transaction differs from a traditional design and construction contract is the impact of Substantial Completion on the Department's liability.

In traditional design and construction contracts, the occurrence of Substantial Completion typically shifts liability for performance of the completed Project from the contractor to the Department. Except for defects covered by the express terms of the contractor's warranty, the Department accepts the work and assumes performance risk thereafter, thereby placing significant importance on the Substantial Completion tests and the methods for satisfying such tests.

By contrast, in a P3 transaction the Developer remains liable for the performance of the Project after Substantial Completion. If the Project does not perform according to the requirements set forth in the Concession Agreement, the Developer cannot rely on the Department's certification of Substantial Completion to avoid deductions to the Availability Payments or seek compensation from the Department due to the occurrence of Substantial Completion. The Department therefore does not "accept" the work in the traditional sense (although the Department's right to seek certain remedies for poorly performed work, such as requiring the Developer to uncover completed portions, may be limited after Substantial Completion). Long term operations and maintenance, and all risks and costs associated with the completed construction work, rest with the Developer. The Developer will typically manage these risks by seeking customary warranties and indemnities from its Design & Construction Contractor (D&C Contractor).

Set forth below is an example of a typical provision providing that the Department accepts no liability for the completed Work notwithstanding any other provision of the Concession Agreement, including as a result of certifying as to Substantial Completion, other than as limited by Applicable Law:

Nothing contained in the [Project Documents] shall in any way limit the right of the [Department] to assert claims for damages resulting from [Defects] in the [Work] for the period of limitations prescribed by [Applicable Law], and the foregoing shall be in addition to any other rights or remedies the [Department] may have hereunder or under [Applicable Law].

When establishing the Substantial Completion test, Departments should bear in mind the different position they are in vis-à-vis the completed work as compared to a traditional design and construction contract. In particular, the Substantial Completion test in a Concession Agreement may be less stringent in some respects than that in a design and construction contract because the Department can rely on performance deductions from the Availability Payments as a means of managing proper delivery of the required specification and will not have liability for correcting any poorly performed work. However, minimum standards are still typically set in case the Department terminates the Concession Agreement following a Developer Default and assumes responsibility for the long-term operation and maintenance of the Project. The Department should therefore strike a balance between requiring a minimum level of quality and giving the Developer sufficient flexibility to meet the performance requirements in innovative and cost efficient ways.

This Chapter considers the extent to which it is appropriate for the Department to require the Developer or its Design-Build Contractor to provide defined levels and/or types of construction performance security in connection with the Project. Common forms of construction performance security include surety bonds, on-demand letters of credit, retention requirements and parent company guarantees. The FHWA recognizes that participants in the P3 market have differing views regarding the relative benefits offered by different forms of construction performance security and the role that each may play in providing support to a Project. The FHWA encourages a robust dialogue with respect to these and other issues, and as a result, this Chapter does not analyze the extent to which there is a role in P3 projects for any particular form of construction performance security, nor the relative strengths and weaknesses of different forms of such security as may be commercially available in the United States. Departments should consult with their legal, financial and technical advisers to determine the type and amount of construction performance security that may be required by law or otherwise advisable for any particular Project. In addition, FHWA's primary role is that of a provider of funding, not an administrator of highway construction programs. Accordingly, FHWA's regulatory requirements for performance bonding (e.g. 23 CFR 635.110) do not specify when or how performance bonding must be used or the amount of such bonding when used, and as a matter of policy FHWA generally defers to the policies and practices employed by recipients of Federal aid, who are responsible for all aspects of highway planning, design, construction, maintenance and operations.

In the United States P3 market to date, the approach taken to construction performance security has varied significantly from State to State and from project to project. Some of the reasons for this are discussed in this Chapter. Some Concession Agreements have not required construction performance security to be provided by the Design-Build Contractor, whereas others have required performance and/or payment bonding in amounts up to as much as 100% of the construction price for the Project.

By way of contrast, in P3 markets outside of the United States, it is unusual for a procuring authority to prescribe minimum levels of construction performance security for a Project in the Concession Agreement. Some of the reasons for the approach taken in other markets are also discussed in this Chapter and may be applicable to Projects in the U.S.

In Design-Bid-Build and Design-Build projects, Departments typically require the contractor to provide performance bonding and, in some circumstances, payment bonding. The typical bonding levels vary from State to State and from project to project, but can range between 10% and 100% of the contract price.

Departments are typically required to demand some level of performance and/or payment bonding as a matter of law (e.g., "Little Miller Acts"). The relevant law in some States may even prescribe the minimum level of performance and/or payment bonding required for each construction project the Department procures. This Chapter does not provide a comparative analysis of the relevant laws of each State on this issue.

In those States where there is no legal requirement for such bonding, the Department would nevertheless, as a matter of best practice, consider the extent to which it should require performance and/or payment bonding from the contractor in respect of the work the Department will pay the contractor to perform. To the extent that the Department requires bonding to be provided, in the absence of a legally prescribed amount, the level of bonding required is typically a function of the complexity of the construction project and the "maximum probable loss" in the event of a contractor default. The basis upon which "maximum probable loss" analyses are typically undertaken is not discussed in this Chapter.

Some Departments also require that the payment and performance of the Design-Build Contractor's obligations to the Department be guaranteed by the parent company, or parent companies, of the Design-Build Contractor. The principal function of such a guarantee is to provide a robust balance sheet with sufficient assets to stand behind the obligations of the Design-Build Contractor in circumstances where the legal entity signing the Design-Build Contract is a subsidiary of a larger corporate organization and depends on financial support from its affiliated organizations. A contract with such an entity is only as strong as the financial commitment from such affiliated organizations, and entering into a guarantee arrangement with a creditworthy affiliate (typically the parent of a corporate group) will contractually oblige the affiliated organizations to provide the Design-Build Contractor with further support in the event the Design-Build Contractor is unable to pay or perform its obligations.

By comparison, as the international P3 market has matured, projects have increasingly adopted construction performance security packages tailored to their specific requirements. The approach taken to each project is a function of the cost and commercial availability of the relevant performance security instruments and the financial strength of the Design-Build Contractor that the Developer proposes to use, as well as the payment mechanisms utilized in the Design-Build Contract.

With respect to payment bonding, the international P3 market, consistent with the international construction market as a whole, has adopted a number of approaches to secure payment of amounts due to subcontractors and suppliers. For example, in Australia subcontractors typically do not look to payment bonds, but rather rely on either a fast-track dispute resolution process for payment disputes under the Building and Construction Industry Payments Act of 2004, or a right to seek payment directly from the Developer under the Subcontractor's Charges Act of 1974. By comparison, French law tightly regulates the use of subcontractors and requires that they either be paid directly by the Developer or that the Design-Build Contractor provide a bank guarantee covering all sums due. Accordingly, the use of payment bonds from surety providers is not a universally adopted approach to securing payments due to subcontractors and suppliers.

Under a traditional Design-Bid-Build or Design-Build contract, the Department suffers the "first loss" in the event of a contractor default (e.g. bankruptcy), and it is for this reason that construction performance security is typically required, as it provides confidence to the Department that notwithstanding the Design-Build Contractor's performance, non-performance or financial condition, the relevant asset will be constructed for the contracted price. Conversely, in a P3 project, the "first loss" is suffered by the equity providers to the Project, and the "second loss" (which only arises if the losses are greater than the level of the equity committed to the Project) is suffered by the senior lenders to the Project. To the extent that there is a "third loss" (which would only arise if the cost to complete the Project was greater than the aggregate of the equity and debt committed to the Project), that loss would be suffered by the Department following the termination of the Concession Agreement, but only to the extent that the level of termination compensation payable by the Department to the Developer results in a loss to the Department. In the event of a termination of the Concession Agreement, however, the level of compensation payable by the Department to the Developer will typically take into account the amount it would cost the Department to complete the construction of the Project, meaning that (all other things being equal) the Department should not suffer any loss as a result of the termination of the Concession Agreement.

In other P3 markets (e.g., Canada, Australia, France and the United Kingdom), the level of construction performance security required to be provided by the Design-Build Contractor for the Project is typically prescribed by the Developer (in consultation with its equity and senior debt providers) on the basis that responsibility for the management of the construction is outsourced to a private Developer and that Developer is responsible for funding the construction cost.

As a practical matter, Departments should bear in mind that performance bonds "travel" with the underlying Design-Build Contract entered into between the Developer and its Design-Build Contractor, meaning that in the event of a termination of the Concession Agreement, the Department would only be able to take advantage of the performance bond (and require the surety to complete the construction) if it agreed to take over the Developer's obligations under the Design-Build Contract (and in respect of which the performance bond had been issued). Although the Concession Agreement can mandate this quite easily, in practice the implementation of this requirement is a more complex undertaking, because the Design-Build Contract will typically be drafted to work in conjunction with the Concession Agreement rather than as a stand-alone document. In other words, the terms of the Design-Build Contract may need to undergo significant amendment to reflect the fact that the Concession Agreement had been terminated, potentially resulting in a negotiation with the relevant surety.

If the Concession Agreement prescribes the form and/or amount of performance security that the Design-Build Contractor must provide in support of the Project, this may cause an unfair advantage or disadvantage to one particular bidder team (e.g., a Design-Build Contractor with comparably high financial strength may be unfairly disadvantaged if it is required to provide the same level of performance security as a Design-Build Contractor with comparably low financial strength), while also adding costs to the proposals of other bidder teams which would not, in the absence of the requirement in the Concession Agreement, have been incurred.

Although some recent Concession Agreements in the United States have not required the Design-Build Contractor to provide defined levels of construction performance security, most P3 projects that have closed to date in the United States have had this requirement. Among the reasons for this:

In addition, where the lenders to a P3 Project determine that a parent company guarantee of the Design-Build Contractor's obligations to the Developer is appropriate in light of the particular entity that a Developer is contracting with, the Concession Agreement will typically mandate that the Department be named as a beneficiary of the guarantee in addition to the Developer and the Lenders.

An Availability Payment concession is essentially a contract between the Developer and the Department to make available a highway ("the Service") in return for periodic payments. The focus is upon the Developer's provision of the long-term availability of the highway as a service instead of a physical asset, as would be delivered under the conventional approach. As such, the concept of "Availability" (and, conversely, "Unavailability") is at the heart of the Concession Agreement. Generally, Availability is measured against conditions the Developer must meet, and naturally, non-compliance with such conditions constitutes Unavailability. Concession Agreements in the United States typically define the meaning of Unavailability.

Central to the definitions of Availability and Unavailability are certain minimum requirements of the Service (the "Availability Requirements" or "Service Requirements") that are specified in the Concession Agreement. Availability Requirements are typically limited to those Elements that are most important to the Department and critical to provision of the Service. This section focuses on the concept and implications of Availability and Unavailability. Availability Requirements are discussed in the next section.

An Unavailability occurrence usually leads to a deduction or adjustment to the Availability Payment ("Unavailability Adjustments"), thereby reducing the Availability Payment the Department pays to the Developer. It is natural that the conditions that together make up the Availability Requirements vary in importance. As such, the financial implications of the Developer's failure to meet a specific requirement are commensurate with the importance of that requirement to the Department (or the Service). The Concession Agreement will therefore categorize requirements and allocate weight to each specific requirement.

Unavailability Adjustments depend on the relative weight of each such specific requirement. For instance, in a highway project, degradation of Service in certain segments may be weighted more heavily than in other segments. Possible reasons include the segment's general criticality to the highway asset's usefulness, the segment's importance during certain time of the day (or day of the week) or similar factors. The weight assigned to each requirement is provided in the form of a factor, and usually defined as "Unavailability Factor." Such Unavailability Factors are typically further classified on the basis of hourly factors (based on the extent of highway Unavailability in a given hour), segment factor (based on the segment of the highway that is subject to Unavailability), time factor (based on the time of the day when the Unavailability occurs), and the like.

The table below contains examples of segment and time factors.

| Segment Factor | ||

|---|---|---|

| Segment Name | Segment Description | Segment Factor |

| A | The part of the highway from [point X] to [point Y] | [0.15] |

| B | The part of highway from [point Y] to [point Z] including ramps and interchanges on [point A] | [0.25] |

| C | The part of the highway starting from [point A] until termination of the highway at [point B] | [0.60] |

| Time Factor | ||

| Time Period | Time Description | Time Factor |

| A | [6 am to 10 am] | [0.25] |

| B | [10 am to 4 pm] | [0.15] |

| C | [4 pm to 7 pm] | [0.35] |

| D | [7 pm to 10 pm] | [0.20] |

| E | [10 pm to 6 am] | [0.05] |

The financial implications of Unavailability and application of Unavailability Adjustments are specifically discussed in Chapter 5 (Payment Mechanism, Performance Monitoring and Financial Model Adjustments).

The Concession Agreement typically provides for a cure period within which the Unavailability can be rectified without the Developer incurring any Unavailability Adjustments. If the Developer fails to rectify the Unavailability within the said cure period, then Unavailability Adjustments are applied from the first moment when Unavailability commenced (including the cure period). The Concession Agreement will usually permit and provide for certain Unavailability of the Service agreed between the Developer and the Department. This typically relates to planned closure ("Permitted Closure") of the Project for certain scheduled maintenance, and Unavailability resulting from a Permitted Closure does not result in Unavailability Adjustments.

An example definition of Unavailability is provided below.

Unavailability means either (a) a [Closure] that is not a [Permitted Closure], and/or (b) an [Availability Fault] that should have been cured but was not so cured during the relevant cure period (if any).

When there is a cure period associated with an [Availability Fault], and such [Availability Fault] is not cured within that cure period, then such [Availability Fault] shall be deemed to have commenced as an [Unavailability] from the moment it first occurred.

Often, the Concession Agreement will contain performance standards or requirements that are not part of the definition of Availability but are expected of the Developer in the delivery of the Service. Performance standards relate to the quality of the Service. As such, non-compliance of the performance standards does not constitute Unavailability but will attract certain performance deductions. Performance standards and performance deductions are dealt with in this chapter and in Chapter 5 (Payment Mechanism and Financial Model Adjustments), respectively.

Availability of the Service is expected to commence upon the Substantial Completion Date of the Project. As noted in Section 2.2, there may be occasions when the Developer is able to achieve Substantial Completion earlier than expected. As further described in Chapter 7 (Contract Term and Nature of the Proprietary Interest), the resulting early Availability of the Service may lead to higher total Availability Payments unless the Term is measured from the Substantial Completion Date. Making higher total Availability Payments by accepting early Availability of the Service may not be ideal for two reasons: (1) in some instances, the Department may have budgetary constraints both in terms of timing and total size of Availability Payments, and (2) it distorts the basis on which the Developer was selected by the Department and provides an opportunity for proposers to "game" the procurement process by proposing unnecessarily long construction periods to gain a windfall. However, there may be instances when it may make economic sense for the Department to accept early Availability of the Service. The Department may therefore provide a financial payment for early Availability that is different from the Availability Payment, and which is based on the economic value of early Availability to the Department. The Concession Agreement will usually address the rights of the Department and financial implications of the Service being available prior to the expected Substantial Completion Date.

It is in the interests of both the Developer and the Department to keep the definition of Availability (or Unavailability) simple, consisting of metrics that are objective and easy to measure. Since the Availability Payment depends on the definition being met, the Developer and its financiers favor a definition that is objective, measurable, and reasonable and seek to avoid criteria which are unachievable or immaterial in the context of the Service as a whole. Additionally, it is important that the Availability Requirements are predictable and certain. Given this, the Department in drawing up the Availability Requirements, should carefully consider its current as well as future requirements in order to minimize the future changes.

Another key consideration in defining Availability (or Unavailability) is monitoring costs including the administration of the Payment Mechanism. Measuring Availability (or Unavailability) can often be complex and time-consuming, resulting in high monitoring costs. The Developer and the Department would ideally both prefer to avoid a complex definition but the definition may have to be specific. In any case, the eventual nature of the definition of Availability (or Unavailability) will have to be considered on a transaction-to-transaction basis.

In the instructions to proposers/request for proposals, the Department will indicate the technical requirements that potential proposers are expected to meet in their proposals. In case the Developer's technical proposal deviates from the Department's requirements, the deviations need to be approved by the Department. Once the Department and the Developer agree on the final requirements, they are incorporated into the Concession Agreement.

Alternatively, the Concession Agreement may also make reference to the instructions to proposers/request for proposals of the Department that contains all relevant Availability Requirements.

At its core, an Availability Payment Concession Agreement is a contract for delivery of the Service by the Developer to the Department, which in theory should motivate the Developer to maximize quality of the Service and minimize lifecycle costs. The Concession Agreement should leave the opportunity for innovative solutions to achieve those objectives in the hands of the Developer. This essentially requires output-based Availability Requirements and performance standards, in which the Developer is not told how and when the activities leading to the delivery of the Service should be performed.

The technical requirements in such an output-based approach focus on the key performance indicators, related to either Availability or quality of the Service through performance standards. Translating this essential philosophy into practice, however, is a challenge.

Public agencies using P3s very often use an input-based approach wherein they prescribe detailed requirements relating to the works and activities that are necessary to deliver the Service. There are two primary reasons: (1) the complexity of implementing such an output-based approach by public agencies that have long been accustomed to procuring projects through conventional delivery approaches (such as design-build or design-bid-build) for decades, and (2) the presence of a large number of input-based requirements and specifications that are included in regulations, standards and policies.

Internationally, of late an increasing number of public agencies take the perspective that they are ultimately only interested in a limited list of Availability Requirements and performance standards and wish to avoid detailed input-based specifications to the extent possible.

Technical requirements are typically classified into two categories: (1) design and construction, and (2) operations and maintenance. For instance, the Department will typically require a certain technical life of the highway as an output requirement, and the design and construction phase is the right time for the Department to monitor and enforce this technical requirement.

As discussed above, the philosophy underpinning a P3 calls for an output-based contractual arrangement. Concession Agreements in many jurisdictions outside the United States typically contain output-based requirements relating to the Availability of the Service. However, Concession Agreements in the United States often have included specific requirements prescribing the design and construction of the highway. These input-based requirements are very similar to the requirements in conventional delivery approaches, including design-build and design-bid-build contracts. Even though such design and construction related requirements are not unique to P3 Concession Agreements, they are briefly discussed below.

The various design and construction topics include - (i) site conditions, (ii) right-of-way acquisition, (iii) environmental requirements and compliance, (iv) utility adjustments, (v) Project schedule and deadlines, and (vi) hazardous materials and/or undesirable materials management and safety, etc. While these topics are typical of most highway projects, specific design and construction related technical requirements in the Concession Agreement cover alignment, lane width, median, drainage, shoulders, sound barriers, intersections, ramps and interchanges, etc.

As in the case of a contract for conventional project delivery, the Concession Agreement typically contains general requirements with respect to design and construction. Specific technical information of the design and construction requirements are included as an annex/exhibit or incorporated by reference to the instructions to proposers/request for proposal.

The [Developer] shall perform the [D&C Work] including [Utility Adjustments] free from defects and in accordance with:

(i) [Good Industry Practice];

(ii) the requirements, terms and conditions set forth in the [Contract Documents], as the same may change from time to time;

(iii) the requirements, terms and conditions set forth in all [Governmental Approvals];

(iv) all [Applicable Law];

(v) the approved [Project Management Plan] and all component parts, plans and documentation prepared or to be prepared thereunder, and all approved updates and amendments thereof;

(vi) the [Project Schedule]; and

(vi) [Safety Standards].

The Concession Agreement usually casts a responsibility on the Developer to use reasonable care to identify, notify and rectify any errors in the design and construction (technical) requirements prescribed by the Department. An example of such a clause is provided below.

The [Developer] shall use reasonable care to identify any provisions in the [Technical Provisions] that are erroneous, create a potentially unsafe condition (including with respect to extreme event performance of the [Project]), or are or become inconsistent with the [Contract Documents], [Good Industry Practice] or [Applicable Law].

Whenever the [Developer] knows, discovers or, in the exercise of reasonable care, should have known or discovered that a provision of the [Technical Provisions] is erroneous, creates a potentially unsafe condition or is or becomes inconsistent with the [Contract Documents], [Good Industry Practice] or [Applicable Law], the [Developer] shall have the duty to notify the [Department] of such fact and of the changes to the provision that the [Developer] believes are the minimum necessary to render it correct, safe and consistent with the [Contract Documents], [Good Industry Practice] and [Applicable Law].

If it is reasonable or necessary to adopt changes to rectify the [Technical Provisions] after the [Effective Date], such changes shall not be grounds for a [Compensation Event], [Delay Event] or other [Claim], unless:

(a) the [Developer] neither knew, discovered nor, with the exercise of reasonable diligence and care, should have known or discovered of the need for the changes prior to commencing or continuing any [D&C Work] affected by the problematic provision, or

(b) the [Developer] knew of, or discovered, and reported to the [Department] the problematic provision prior to commencing or continuing any [D&C Work] affected by the problematic provision and the [Department] did not adopt reasonable and necessary changes.

If the [Developer] commences or continues any [D&C Work] affected by such a change after the need for the change was known, discovered, or should have been known or discovered through the exercise of reasonable care, the [Developer] shall bear any additional costs and time associated with redoing the [D&C Work] already performed.

Inconsistent or conflicting provisions of the [Contract Documents] shall not be treated as erroneous provisions under this section/article, but instead shall be reconciled under [Section [X]] of this [Concession Agreement].

Typically, the Concession Agreement contains procedures for certification of the Developer's Work, including the design and construction quality, and the Developer is required to follow these procedures to secure necessary certifications, which is discussed in Chapter 2 (Completion Testing and Performance Security).

Additionally, it is possible that the Developer may deviate from agreed standards, and such deviations may or may not be acceptable to the Department. The Concession Agreement usually includes a process to implement deviations from prescribed technical requirements and governs their impact on the rights and duties of both the Developer and the Department. This topic is covered in further detail under Chapter 10 (Department and Developer Changes).

As in the case of design and construction requirements, the main part of the Concession Agreement typically contains the general requirements with respect to operations and maintenance (O&M) with specific technical details of the O&M requirements included as an annex/exhibit or incorporated by reference to the instruction to proposers/request for proposal.

It is worth noting that Availability Requirements and performance standards tend to differ between the construction and operations phases, specifically in brownfield highway P3 transactions, where a part of the highway may be operational while design and construction on another part of the highway is still underway.

(a) The [Developer], at its sole cost and expense unless expressly provided otherwise in this [Concession Agreement], shall comply with all [Technical Provisions], including [Safety Standards] throughout the [Term].

(b) [Section [X]] of the [Technical Provisions] sets forth minimum requirements related to [O&M During Construction] and [O&M After Construction].

(c) The [Developer's] failure to comply with such requirements shall entitle the [Department] to the rights and remedies set forth in this [Concession Agreement], including [Unavailability Adjustments] and/or [performance deductions] from payments otherwise owed to [Developer], and termination for uncured [Developer Default].

A non-exhaustive list of O&M activities to be performed in a typical highway Project O&M include - (i) general operations and maintenance both during construction and after the Substantial Completion Date, (ii) compliance with safety standards, (iii) management of hazardous and undesirable materials, (iv) policing, security, and incident response, etc.

While it is expected that the Developer needs to perform these O&M activities, the focus in an Availability Payment-based Concession Agreement is not the various O&M activities in and of themselves, but the eventual Availability (or Unavailability) of the Service at the agreed Availability Requirements and meeting of performance standards. Typical O&M related Availability Requirements and performance standards include (i) incident response and removal of broken vehicles, (ii) lighting and signs, (iii) pavement, medians, landscaping, and drainage, (iv) tolling facilities and services (if any), etc. This is only an illustrative list of requirements as Availability Requirements and performance standards are based on the specific nature and needs of each project.

Failure to meet the required Availability Requirements typically leads to an "Availability Fault", "O&M Violation" or the accumulation of Non-Compliance Points based on the classification of the requirement in question. Specific Availability Faults and O&M Violations are listed in the Concession Agreement. A non-exhaustive list of Availability Faults and O&M Violations is provided in the below table.

| Availability Faults | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asset | Minimum Requirement | Cure Period | Interval of Recurrence* |

| Pavement Potholes | Pavement within the construction limits shall not have a defect greater than [1/2 square foot] in area including any single measurement of [1-1/2 inches] or greater in depth | [X minutes/hours] | [X minutes/hours] |

| Flooding | No portion of a lane can have standing water | [X minutes/hours] | [X minutes/hours] |

| Roadway Surface Debris |

Conduct the removal and disposal of debris from travel lanes, including at a minimum, large objects, dead animals and tires | [X minutes/hours] | [X minutes/hours] |

* Please see Section 5.1.4 regarding the implications of the prescribed interval of recurrence.

| O&M Violations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Task | Minimum Requirement | Cure Period | Interval of Recurrence |

| Litter Removal | Monitor and pick-up, remove, and properly dispose of litter | No more than three cubic feet per acre of litter | [X minutes/hours] | [X minutes/hours] |

| Fuel Spills/ Contamination | Contamination management plan | Provide Contamination Management Plan after a fuel spill/contamination event |

[X minutes/hours] | [X minutes/hours] |

| Highway Lighting | Maintain highway lighting at acceptable level of safety for traveling public | Maintain the highway lighting system with a minimum of [X] percent (X%) of highway lighting (including overhead, underdeck and sign lighting) operational and no more than [X] luminaries out in a row | [X minutes/hours] | [X minutes/hours] |

| Graffiti | Continually monitor and maintain assets free of graffiti and promptly remove or cover graffiti | Graffiti shall be removed, covered or painted over to match the color and the painted application finish of adjacent area | [X minutes/hours] | [X minutes/hours] |

| Vegetation Control on Concrete Slopes and Concrete Surfaces | Continually monitor concrete walls, sound barrier walls, concrete slopes, retaining wall, sidewalks, etc. | Concrete surfaces shall be kept free of vegetation Vegetation shall not be allowed to grow between concrete joints on slopes, bridges, walls, sidewalk or curb & gutter sections. |

[X minutes/hours] | [X minutes/hours] |

A general requirement in the Concession Agreement is that the Developer performs the O&M Work in a manner consistent with Good Industry Practice (as it evolves from time to time), Applicable Laws, and Governmental Approvals. The need to meet these standards is both understandable and reasonable from the perspective of the Developer, to the extent the changes in them over time do not lead to material additional costs to the Developer. If the Availability Requirements and performance standards are truly output-based, then the Concession Agreement should provide for sufficient flexibility for the Developer to incorporate such changes.

On the other hand, if the O&M requirements are input-based, changes in good industry practice makes the technical requirements obsolete for the Developer, and the transfer of such a risk to the Developer may not lead to value-for-money for the Department. Therefore, instead of prescribing specific asphalt mix requirements and maintenance periodicity requirements that are input-based, the Department could set pavement quality requirements in terms of longitudinal roughness, patch work, rutting and cracking, all of which take the form of output-based specifications. Additionally, in the context of highway lighting, the Department could set requirements in terms of lumens per square foot (lux) rather than prescribing the Developer to use lighting equipment of specific type and nature (lamp's size, wattage, center length, etc.).

General Requirements

(a) The [Developer] shall carry out the [O&M Work] in accordance with:

(i) [Good Industry Practice], as it evolves from time to time;

(ii) the requirements, terms and conditions set forth in the [Contract Documents], as the same may change from time to time;

(iii) [Applicable Law];

(iv) the requirements, terms and conditions set forth in all [Governmental Approvals];

(v) the approved [Project Management Plan] and all component parts, plans and documentation prepared or to be prepared thereunder, and all approved updates and amendments thereof;

(vi) the approved [Operations and Maintenance Plan], and all approved updates and amendments thereof;

(vii) the approved [Maintenance Plan], and all approved updates and amendments thereof;

(viii) [Best Management Practices];

(ix) [Safety Standards]; and

(x) all other applicable safety, environmental and other requirements, taking into account the [Project Right of Way] limits and other constraints affecting the [Project].

(b) If the [Developer] encounters a contradiction between clauses (i) through (x) above, the [Developer] shall advise the [Department] of the contradiction and the [Department] shall instruct the [Developer] as to which subsection shall control in that instance. No such instruction shall be construed as a [Department Change].

(c) The [Developer] is responsible for keeping itself informed of and applying current [Good Industry Practice].

Management of Hazardous Materials and/or Undesirable Materials

The [Developer] shall manage, treat, handle, store, remediate, remove, transport (where applicable) and dispose of all [Hazardous Materials] and/or [Undesirable Materials] encountered in performing the [O&M Work], including contaminated soil and groundwater, in accordance with [Applicable Law], [Governmental Approvals], the [Hazardous Materials Management Plan] and/or [Undesirable Materials Management Plan], [Best Management Practice], and all applicable provisions of the [Contract Documents], including the [Technical Provisions].

Environmental Compliance

(a) In the performance of [O&M Work], the [Developer] shall comply with all [Environmental Laws] and perform or cause to be performed all environmental mitigation measures required under the [Contract Documents] or under the [Environmental Approvals], including the consents and approvals obtained thereunder, and shall comply with all other conditions and requirements thereof.

(b) The [Developer], at its sole cost and expense, shall also abide by and comply with the commitments contained in the environmental impact documentation related to the [NEPA/CEQA Approval] and any additional commitments contained in subsequent re-evaluations and [Environmental Approvals] required for the [Renewal Work].

As in the case of design and construction standards/requirements, the Concession Agreement typically provides for deviations in O&M standards/requirements by the Developer. Any such deviation needs to be approved by the Department in accordance with the procedure laid down in the Concession Agreement. Deviations initiated by the Developer are dealt with as a Developer Change, which is discussed in Chapter 10 (Department and Developer Changes).

The Department too can initiate a change to the O&M standards/requirements, and such a change ("Department Change") can be classified either as (1) Discriminatory O&M Changes, or (2) Non-Discriminatory O&M Changes. As the Concession Agreement is a long-term contract, the Department may fear locking itself to specific O&M requirements without the flexibility to change them over time. Consequently, the Concession Agreement allows for Department Changes under limited circumstances and conditions. Department Changes are further discussed in Chapter 10 (Department and Developer Changes).

The Term of an Availability Payment concession generally ranges from 30 to 40 years, although the Term will ultimately depend on the nature of the Project, the authorizing legislation and the needs (and relative bargaining power) of the parties. On termination or expiration of the Term, the Project will generally pass back to the Department. Because the Department will be responsible for operating and maintaining the Project after the end of the Term, it will have a strong interest in ensuring that all of the Project assets it receives are not in a condition that will require immediate and costly life-cycle maintenance. The Developer, by comparison, will naturally seek to minimize its costs and may be unlikely to voluntarily make long-term investments in the Project during the final years of the Term (as it will not receive much of the benefit of those investments). Although the ongoing performance specifications contained in the Concession Agreement would require the Developer to comply with such items as ride quality and cracking of the roadway, there is nevertheless a risk that the Developer could defer necessary renewals and instead choose to incur additional routine maintenance costs, together with the possibility of incurring noncompliance deductions for failure to meet performance requirements. This is a particularly sensitive issue in Availability Payment transactions, as the typical life of some Project Elements (such as bridges) may be only slightly longer than the Term, which reduces the natural incentive for the Developer to perform life cycle maintenance that might be present in a transaction with a longer Term. For this reason, special attention should be paid in the Concession Agreement to the means and methods of measuring the expected residual life of key Elements to ensure that the Developer does not hand back a Project to the Department requiring extensive major maintenance.

The Concession Agreement should therefore include provisions for dealing with what will happen to the Project (and particular assets) at the end of the Term, including the rights and obligations of the Department and the Developer with respect to the long-term condition of the Project on Handback, including any Residual Life Requirements of the Project assets. These provisions are important to avoid disputes at the end of the Term and also to incentivize the Developer to make life-cycle investments in the Project at the appropriate time. The extent of the obligations the Department places on the Developer with respect to the Handback condition of the Project may be reflected in the pricing of the Developer's bid for the Project and may have an impact on the design, construction, or maintenance strategies considered during the procurement process.

Generally, the Developer will be required to transfer the Project back to the Department in accordance with prescribed Handback Requirements. From the Department's perspective, Handback Requirements are particularly important in incentivizing the Developer to renew and replace Elements of the Project at the optimum time (from a life-cycle perspective), rather than perform the minimum maintenance required and, as described above, possibly accept some payment deductions for breach of its performance requirements. The Developer will seek to economize its long-term life-cycle costs in light of the performance specifications required under the Concession Agreement, so a well-defined set of Handback Requirements will likely impact the Developer's approach to operations and maintenance at all stages of the Project life-cycle. In particular, the Department should give careful consideration to complex assets, such as bridges, tunnels and other major structures, because properly crafted Handback Requirements can encourage the Developer to invest in these assets early and avoid the need for the Department to undertake expensive replacement efforts after the end of the Project.

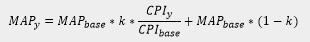

Handback Requirements are generally contained in a schedule to the Concession Agreement within the technical specifications for the Project and should include the Developer's obligations, including valuation methodologies and inspection requirements, in relation to maintenance and condition of each Element of the Project during what is known as the Handback Period, generally commencing five years prior to the end of the Term.