December 4-5, 2019

Austin, Texas

This report highlights noteworthy practices and key recommendations identified in the Every Day Counts Round 5 (EDC-5) peer exchange focused on value capture held December 4-5, 2019 in Austin, Texas.

The EDC Program identifies and deploys proven-yet-underutilized innovations to shorten the project delivery process, enhance roadway safety, reduce traffic congestion, and integrate automation. Proven innovations promoted through EDC facilitate greater efficiency at the State and local levels, saving time, money and resources.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) works with State departments of transportation (DOT), local governments, Tribes, private industry, and other stakeholders to identify a new collection of EDC innovations to champion every two years. EDC facilitates regional summits for transportation leaders to discuss and identify opportunities to implement the innovations that best fit their needs. Following the summits, States finalize their selection of innovations, establish performance goals for the level of implementation and adoption over the upcoming two-year cycle, and begin to implement the innovations with the support and assistance of FHWA technical teams.

Value capture was identified as one of the ten EDC-5 innovation techniques for the 2019-2020 cycle.

The Texas peer exchange was the second in a series of EDC-5 peer exchanges aimed at facilitating knowledge transfer and capacity building by connecting peers from neighboring States and/or agencies to exchange best practices about value capture. The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) requested the peer exchange to learn about methods of implementing value capture techniques in their respective states, specifically focused on innovative project financing and delivery.

Rafael Aldrete, Ph.D., Senior Research Scientist at Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI), served as a subject matter expert (SME) on value capture, presenting on best practices.

Prior to the exchange, representatives from FHWA's Center for Innovative Finance Support, Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty (HEP), and the Volpe Center worked with TxDOT to identify peers that would be able to share their experiences, lessons learned, and recommendations for using value capture techniques to finance transportation infrastructure projects. The peers selected for the exchange were:

The two-day peer exchange was held December 4-5, 2019, at the Omni Austin Hotel at Southpark in Austin, Texas. Participants included the four peer presenters, facilitators from the Volpe Center, Dr. Aldrete, and representatives from the following organizations (in alphabetical order): Alamo Area COG, Capital Area MPO, Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority, City of Austin, City of El Paso, City of Laredo, City of Phoenix, City of Texarkana, Downtown Austin Alliance, El Paso MPO, Heart of Texas COG, Houston-Galveston Area Council, Longview MPO, Midland Development Corporation, North Central Texas Council of Governments, Permian Basin MPO, Permian Basin Regional Planning Commission, San Angelo MPO, Texas A&M University, Town of Horizon City, TxDOT, and Victoria MPO. Approximately 47 people from various groups and agencies attended the two-day event. A full list of attendees is available in Appendix B of this report.

The exchange began with a brief round of introductions and remarks from TxDOT on their goals for the exchange. The morning sessions on the first day included an overview of value capture techniques from the State and Regional perspective, followed by a discussion on the applicability and legislative framework of certain value capture techniques in Texas. The afternoon session began with an in-depth overview on Transportation Reinvestment Zones (TRZs), followed by a discussion on Joint Development (JD). Sessions on the second day included an overview of impact fees, developer agreements, and sales tax districts, with a closing conversation that focused on key takeaways and next steps for the implementation of value capture techniques in Texas. An agenda for the program is included in Appendix C of this report.

The Peer Exchange was followed on Thursday afternoon by the Texas State Transportation Innovation Council (STIC) annual meeting, and many attendees attended both meetings.

Value capture refers to a set of techniques that take advantage of increasing property values, economic activity, and growth linked to infrastructure investments to help fund current or future improvements. Value capture is rooted in the notion that public investment should generate public benefit.

FHWA and Dr. Aldrete provided materials describing in depth the techniques of value capture and the benefits realized through their implementation. An overview of value capture categories, techniques, and definitions are in Appendix D of this document.

Over the course of the two-day exchange, the peers shared their professional experiences and engaged in discussion about value capture projects. Example techniques and projects are shared below.

Value capture techniques like transportation reinvestment zones (TRZ) help capture organic property value increases within designated districts. Without increasing the tax rate, TRZs can be used to capture both present and future economic growth created as a result of the transportation investments, and they may be used in conjunction with other value capture methods. Once the zone is created, a base year is established, and the incremental increase in property tax revenue that is collected from parcels within the zone is used to finance transportation improvements in the predetermined area.

Julie De Hoyos, Project Finance and Operations Director, Texas Department of Transportation, presented on the TRZ process, providing Texas specific examples and context throughout. TRZs were written into Texas legislation in 2007, tied to the State's pass-through financing program, which allows local communities to fund upfront costs for constructing a state highway project, and have the state reimburse a portion of the project cost to the community over time. In 2011, TRZs were decoupled from the pass-through program.

TRZs can be established as a local value capture tool in Texas, with three taxing entities written into legislation: counties, municipalities, and port authorities/navigation districts. Given that Texas law allows for the implementation of multiple value capture techniques, including Tax Increment Reinvestment Zones (TIRZ) and Tax Increment Financing (TIF), TxDOT recommends the following considerations be included in a TRZ feasibility analysis:

Additionally, an entity with an established TRZ can use the captured funds directly toward a transportation project or as a pledge for a financing method such as tax increment bonds and TxDOT State Infrastructure Bank (SIB) Loans. The SIB issues loans to any public or private entity authorized to construct, maintain, or finance an eligible transportation project. Projects funded with a SIB loan must be eligible under federal highway programs and be consistent with the Statewide Transportation Improvement Plan (STIP). Eligible uses outlined in Table 1.

| Eligible Uses Include: |

|---|

| Planning, environmental, and feasibility studies |

| Construction |

| Utility relocation |

| Right of way acquisition |

| Appraisal and testing |

| Engineering, surveying, and inspection |

| Financial & Legal advisory fees |

The TRZ Implementation process is divided into five stages, and detailed below.

Since their inception in 2007, Texas has 14 active TRZs in varying stages of implementation: six municipal, four county, and four port authority. Because of this robust network, Texas has been able to identify a number of opportunities and limitations. Of the opportunities were: establish partnership opportunities with a common goal, establish multimodal networks resulting from a comprehensive project scope, and realizing that TRZs are easier to operate compared to other innovative finance mechanisms.

Terry Quezada, Director of Capital Improvement Plan, Town of Horizon City, TX, presented on Horizon City's use of a TRZ in the Eastlake Extension project. As outlined in the 2013 El Paso County Comprehensive Mobility Plan, the Town of Horizon City adopted a TRZ in 2014 that was projected to generate approximately $5 million to fund the Eastlake Extension Phase 2 project. The Phase 2 project is a three-party agreement, relying exclusively on three local entities: the Town of Horizon City, the County of El Paso, and the Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority (CRRMA). Each entity has specific roles, which are outlined below in Table 2.

| Entity | Role |

|---|---|

| Town of Horizon City |

|

| County of El Paso |

|

| CRRMA |

|

Horizon City's TRZ followed the implementation process outlined in Table 1. The payments for Horizon City begin in 2020, with graduated payments through May 2038. The first payment will be $29,011, and the final payment will be $852,816. For FY20, the TRZ is projected to contribute $99,001 in new tax revenue.

Joint developments involve monetizing the unused land use entitlements on publicly owned property by transferring them to private developers for some form of revenue and/or cost-sharing arrangements. These developments can involve sale or lease of development rights above, below, or adjacent to transportation rights-of-way, such as above railroad tracks or expressway turnpikes. These tools often can serve as the means to meet larger policy goals, such as promoting transit-oriented development.

Rafael Aldrete, Ph.D., Senior Research Scientist, TTI, presented on the difference between joint development and interface fees, providing three geographically different examples. A joint development fee is paid to the government for the ability to develop public land or air rights adjacent to a transportation facility, whereas interface fees are paid to the government for the ability to create and maintain a direct connection from private property to a transit facility.

Rafael's first case study was The Cap at Union Station Project in Columbus, Ohio. When Interstate 670 was constructed in the 1970s, the City of Columbus was divided in two. In the 1990s, the City proposed the expansion of I-670, and in order to gain community support, proposed a cap on the highway to reconnect both sides of the city.

The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) and the City of Columbus agreed to pay just under $10 million for the construction of The Cap, and private developers signed an agreement to lease the platforms and construct the buildings for $7.8 million. Additionally, the City agreed to charge developers $1 per year in exchange for 10% of the annual development profits. In order to retain the 10% of annual profits, FHWA requires the fair market rent be charged on residential units in the project boundary. During the process, the City and State ran into two problems that serve as lessons learned for future projects: identifying the owner of the air rights and the title search. While these two issues were eventually resolved, they required more effort than was expected, and impacted the project's timeline.

Completed in 2004, The Cap consists of 25,500 square feet of retail development, two pedestrian bridges, and a bridge for vehicle traffic. The project has since increased pedestrian and business accessibility, as well as the connectivity of the downtown.

Rafael's second case study featured the Kylde Warren Park in Dallas, Texas. This 5.2 acre park, plaza, and urban green space was built over the recessed Woodall Rodgers Freeway in downtown Dallas, reconnecting Uptown and the Arts District. After opening in 2012, the park covers three blocks and includes gardens, plazas, foundations, a lawn, a performance stage, a playground, a dog park, and space for food trucks.

The project totaled $110 million, and was funded through a variety of sources. $20 million came from federal and state highway funds, $16.7 million came from American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds, and $20 million was dedicated through a City bond election. Private funds from real estate developers and charitable foundations made up the remaining $53.3 million. The public-private partnership extends to the park's operation as well, as the City of Dallas owns the park, and the Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation operates and maintains the space. Revenue comes from event hosting and rent from a restaurant located inside the park. The park and its adjacent area are designated as a Public Investment Development (PID) district in which the owner pay additional tax to the government, and the tax is then used in that designated area.

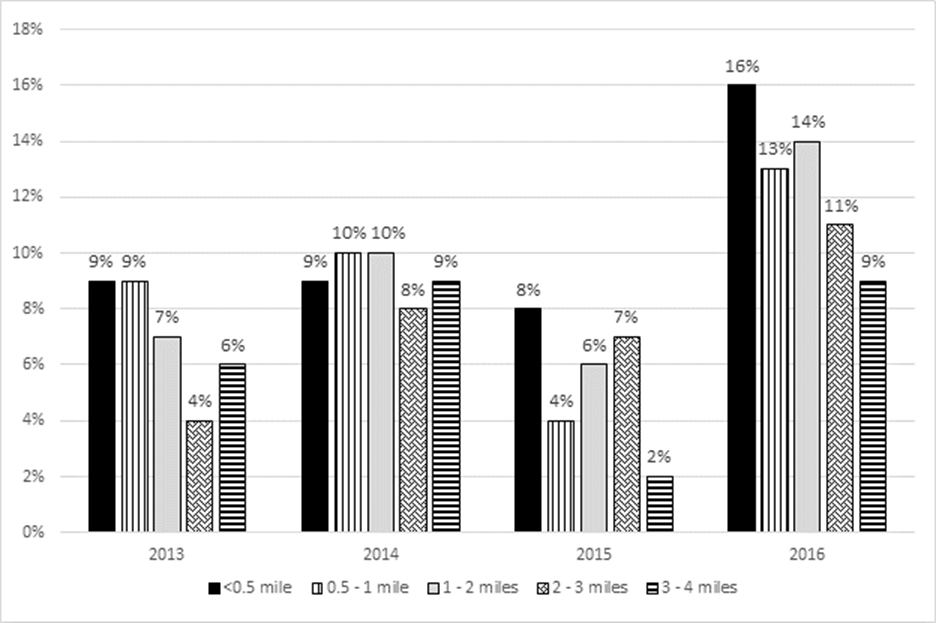

Since Clyde Warren Park has opened, there has been a continuous increase in the municipal property tax base, with the largest increases occurring within one mile of the highway centerline. These data are shown below in Graph 1. Additionally, from 2012 to 2015, the rent price of four residential buildings near the park increased, on average of 49.5%.

Rafael's final joint development example was the I-395 Capital Crossing Project in Washington, DC. This project, which dates back to 1989, is a response to the division between the Capitol Hill and East End neighborhoods that was created by the construction of I-395 in the 1960s. The project is the largest air rights project ever undertaken in Washington, and is expected to be completed by 2021.

This $1.3 billion project will create a seven-acre decked development site above I-395, with five mixed-use buildings, including one residential building with 20% affordable housing, and parking for 11,146 vehicles. The total cost for this project includes no federal or municipal funds, meaning that taxpayers are not involved in this project. Of the total project cost, $270 million is dedicated for transportation improvements, and will be paid by the real estate developer, Property Group Partners (PGP). These improvements include utility relocation, reconfiguration of interstate on and off ramps, enhanced pedestrian and bicycle connections, and the restoration of the original street grid. In addition to this $270 million private investment, PGP initially paid $120 million in an air rights fee in 2012 to acquire the property. Once this project is completed, Washington is expected to receive $40 million in new, annual tax revenue from this project.

This project was successful because of clear objectives from the start, as well as strong coordination and partnerships between community leaders, municipal planners, FHWA, and local residents.

Impact fees, which are also referred to as developer contributions, are the financial responsibilities that local governments place upon developers to provide some or all of the public improvements necessitated by their development projects. They are generally imposed as conditions of approval at major project milestones and directly linked to land use entitlements. As most contributions are collected at the project onset, projects funded through this value capture mechanism have flexibility to generate and use funds early when the public improvements are generated. Impact fees are different from other forms of value capture, as they can be used to pay for off-site services such as local roads, schools, or parks, that are needed to support new development.

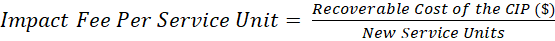

Impact fees are determined by either the inductive or deductive method, both of which capture the cost of the additional infrastructure that is required by new development. The inductive method is more general, capturing the cost of generic facilities, while the deductive method uses growth projections to determine infrastructure need. Both of these methods must meet the rational nexus test, meaning that they must demonstrate that the amount of the impact fee is reasonable given the new infrastructure provided by the fee. These fees cannot be spent on operations, maintenance, and non-capacity improvements.

Liane Miller, Business Process Consultant, City of Austin Transportation Department, presented on Austin's Street Impact Fees. The City, in search of a method that allows for growth to pay for growth that is equitable, predictable, and transparent, implemented Street Impact Fees (SIF), which are a one-time fee for new development that represents that cost of growth for street infrastructure.

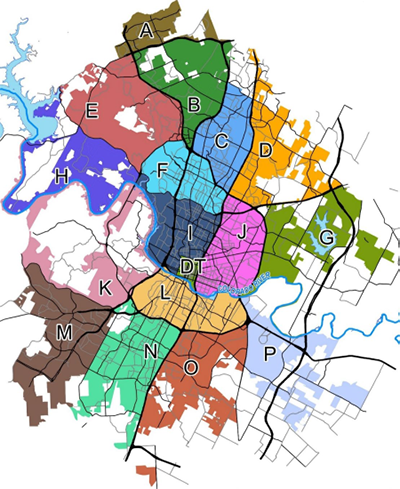

The City of Austin developed a calculation for the cost of street growth infrastructure that captured the cost over the next 10 years, establishing service areas and developing land use assumptions within those areas. They City also developed a Roadway Capacity Plan to accommodate growth within each service area. To date, Austin has 17 different service areas, each with a maximum of 6 miles, in accordance with Texas state law.

Austin divided its Street Impact Fee into three implementation phases, which included:

Considerations for the development of service areas includes geography and transportation characteristics (i.e. Colorado River, Downtown, and Interstate boundaries). The land use assumptions were developed with population and employment projections; expected demands for infrastructure; reference to master plans, demographics, and growth rates; and reference to a previous water/wastewater impact fee study. The Roadway Capacity Plan includes all roads that have been designated on an officially adopted roadway plan of the political subdivision, together with all necessary appurtenances, in accordance with Texas law. Similarly, the Plan had to connect with the Austin Strategic Mobility Plan, which is a coordinated transportation strategy for all modes that supports the growth concept of Imagine Austin, the City's comprehensive plan for the future. Austin is currently in Phase 3, and is working on a Study Assumptions Report. Approved in August 2019, this report includes service areas, growth projections, and the completed Roadway Capacity Plan.

As part of the Phase 3, the City must conduct a Study Assumptions Report, which will include the calculation for impact fees. This calculation considers land use and population projects and removes costs associated with existing development and growth at more than 10 years. The Report uses the following equation to calculate the maximum assessable impact fee:

. After this report determines the maximum fee, the City Council determines the effective rate.

. After this report determines the maximum fee, the City Council determines the effective rate.

Once the Report is complete, the City will collect comments from the impact fee advisory committee and receive public feedback on the policy and fee. After this, the City will make changes to the program if needed, and move to the implementation phase.

Ray Dovalina, Street Transportation Director, City of Phoenix, provided an overview of the City's impact fee program and sales tax initiative. The State of Arizona enacted impact fees in 1988, with the passage of a 20-year sales tax of 0.4% to support statewide transit infrastructure and operations in 2000. Both the City and State have enacted a number of innovative finance techniques since then, and most recently in 2015, Phoenix voters approved a 35-year 0.3% increase to sales tax in the city to support both public transportation and street transportation needs. This will generate $16.7B over 35 years.

The Impact Fee is charged only in designated areas, and can only be used for capital expenditures and provide the capacity for new demand. The fees must fall in four categories: population, land area, traffic projections, and usage. For traffic projections, impact fees can only be leveraged on major arterials. The City is also looking at how to more appropriately assess pass through traffic so they are not disproportionately affecting the impact fees.

The City of Phoenix also has a sales tax initiative that is used to support their citywide transportation initiative, Phoenix Transportation 2050, which began in August 2014. These two initiatives were created, in part, because Phoenix is expected to add roughly 700,000 residents by 2040, with a transit system cannot sustain that level of growth. Back in 2000, when the City invested in improved service, they experienced a 57% growth in transit ridership. Because of this, there is enormous potential in Phoenix to realize the benefits of improving transit service as a means to keep up with a growing population.

Phoenix Transportation 2050 calls for more late night service, more frequency on bus routes, street repairs, walkable and bikeable streets, technology improvements, WiFi, and more. The goal was to develop a citywide transportation plan that funds street improvements, provides mobility choices and better access, supports economic prosperity, and future growth. In order to do this, the City implemented an addition 0.3 percentage point tax increase, totaling a 0.7% sales tax on purchases in the City of Phoenix. This increase will provide an additional $6.8M in funding, contributing to 22% of the total plan funding sources. This increase is mostly dedicated to new funds for street repair, sidewalk and bike lane installation, the majority of additional funding for bus routes, and rail construction and operation.

In order to make these two innovative finance techniques successful, the City of Phoenix had strong political backing and engaged community groups. They used these resources to advocate for legislative changes that allowed the initiatives to evolve and provided a multifaceted approach to all new projects and initiative with a central goal of economic growth.

This section highlights overall key takeaways by TxDOT and for other attendees that are planning or seek to plan value capture projects. It summarizes the key recommendations that emerged from the peer exchange and profiles noteworthy practices employed by peer agencies and organizations.

Create a coherent and clear message for decision makers. Most transportation decisions are not made at the staff level, so crafting a narrative that clearly outlines the benefits of value capture techniques to executive decision makers and leadership is paramount to being able to implement them.

Develop non-technical and non-legal communication materials for decision makers. The individuals making the decisions about value capture implementation often require short and concise communication materials to prove that something is a worthy of implementation. Something such as a briefing book, infographics, or directed, stakeholder-specific workshops would be useful.

Looking at transportation assets in a different way helps to identify more potential for value capture. Transportation agencies are good at creating and implementing transportation projects, but rarely focus on how to get financial value out of them. Shifting focus and culture to think of transportation assets as those that can yield assets will be helpful in future implementation.

Value capture needs a champion. In order to effectively implement value capture techniques, each agency needs an internal staff member or member of leadership to continue to internally and externally advocate for value capture.

Value capture implementation must adapt to local context and concerns. There is no one-size-fits-all approach for value capture or any one technique.

Public education campaigns about the benefits of value capture projects may be needed. Public sentiment can be a challenge. Agencies may need to invest in open communication methods to educate the public about what value capture techniques are and how they will impact communities.

Thay Bishop, CPA, CTP/CCM

Senior Program Advisor

FHWA Center for Innovative Finance Support

61 Forsyth Street, Suite 17T26

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 562-3695

Stefan Natzke

National Systems & Economic Development Team Leader

FHWA Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

(202) 366-5010

| Name | Agency |

|---|---|

| Sean Scott | Alamo Area COG |

| Ashby Johnson | Capital Area MPO |

| Mary Temple | Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority |

| Liane Miller | City of Austin |

| Yvettte Hernandez | City of El Paso |

| Danny Magee | City of Laredo |

| Ray Dovalina | City of Phoenix |

| Tracie Lee | City of Texarkana |

| Casey Burack | Downtown Austin Alliance |

| Eduardo Calvo | El Paso MPO |

| Roger Williams | El Paso MPO |

| Ben Hawkinson | FHWA |

| Stefan Natzke | FHWA |

| Jill Stark | FHWA |

| Jose Campos | FHWA Texas Division |

| Kirk Fauver | FHWA Texas Division |

| Tymli Frierson | FHWA Texas Division |

| Mike Leary | FHWA Texas Division |

| Justin Morgan | FHWA Texas Division |

| Ramesh Gunda | Gunda Corporation |

| Rep Pledger | Heart of Texas COG |

| Adam Beckom | Houston-Galveston Area Council |

| Macie Wyers | Longview MPO |

| Gary Law | Midland Development Corporation |

| Brian Dell | NCTCOG |

| Travis Liska | NCTCOG |

| Cameron Walker | Permain Basin MPO |

| Virginia Belew | Permain Basin Regional Planning Commission |

| Major Hofheins | San Angelo MPO |

| Amir Hessami | Texas A&M |

| Terry Quezada | Town of Horizon City |

| Rafael Aldrete | TTI |

| Charles Airiouhuodion | TxDOT |

| Mohammad Al Hweil | TxDOT |

| Marty Boyd | TxDOT |

| Julie De Hoyos | TxDOT |

| Susan Fraser | TxDOT |

| Sara Garza | TxDOT |

| Thomas Nielson | TxDOT |

| Shelley Pridgen | TxDOT |

| Raymond Sanchez | TxDOT |

| Mansour Shiraz | TxDOT |

| Yue Zhang | TxDOT |

| Darcie Schipull | TxDOT San Antonio District |

| Benjamin Bressette | U.S. DOT Volpe Center |

| Terrance Regan | U.S. DOT Volpe Center |

| Maggie Bergeron | Victoria MPO |

FHWA EDC5: Value Capture Peer Exchange

Agenda for Texas Value Capture Techniques Peer Workshop

Dates: December 4-5, 2019

Exchange Host: Texas DOT

Exchange Location: Omni Hotel Southpark, 4140 Governors Row, Austin, Texas

Length of Exchange: 1.5 days (starting on afternoon of day 1 and full day on day 2)

Peers:

Subject Matter Expert: Rafael Aldrete, Ph.D.

| Time | Topic | Presenter |

|---|---|---|

| 8:30 a.m. | Welcome and Overview Facilitator welcomes attendees, reviews the agenda, describes documentation/follow-up, and establishes ground rules for discussions. |

TxDOT; FHWA & Volpe Facilitator |

| 9:00 a.m. | Value capture vision from the State and Regional Perspective Welcome and discussion of value capture uses and potential from the Federal, State, and Regional perspective. This includes an introduction to the potential that value capture techniques that may have for Texas MPOs, municipalities, and other transportation agencies.

|

|

| 10:30 a.m. | Break | |

| 10:45 a.m. | Value capture techniques overview and applicability in Texas Detailed overview of value capture techniques that are currently used and those that may be suitable in the future within Texas. There will be an opportunity for participants to discuss those areas they are most interested in hearing about. |

Rafael Aldrete, TTI |

| 11:45 a.m. | Lunch | |

| 12:30 p.m. | Transportation Reinvestment Zones (TRZs) This session will provide an overview of transportation reinvestment zones, a value capture technique currently used in Texas. The discussion will cover the role and perspective of TxDOT at the state level, as well as the experience with the utilization of the technique from a local government perspective.

|

|

| 2:00 p.m. | Break | |

| 2:15 p.m. | Joint Development

|

|

| 3:45 p.m. | Wrap-up and charge for day 2 Solicitation from participants of key take aways from day 1 and the identification of potential technical assistance that would be useful in aiding agencies in exploring the uses and implementation of value capture. Discussion includes:

|

Facilitator |

| 4:30 p.m. | End of day 1 |

| Time | Topic | Lead Presenter |

|---|---|---|

| 8:30 a.m. | Welcome and Overview of the Day Facilitator welcomes attendees, reviews the key take aways from Day 1 and provides context for Day 2 |

Facilitator |

| 8:45 a.m. | Impact Fees/Developer Agreements/Sales Tax Districts

|

|

| 10:30 a.m. | Break | |

| 10:45 a.m. | Discussion, Identification of Key Take Aways, and Next Steps

|

Facilitator |

| 11:30 a.m. | Wrap-up, Follow-up Actions and Adjourn | Facilitator |

| 12:30 pm | Texas STIC meeting attendees will begin arriving at 12:00 noon and the STIC meeting will begin at 12:30 pm in the same room. |

Provided by Julie Kim, SME.

| Category | Technique | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Developer Contributions | Impact Fees | Fees imposed on developers to help fund additional public services, infrastructure, or transportation facilities required due to the new development. |

| Negotiated Exactions | Negotiated charges imposed on developers to mitigate the cost of public services or infrastructure required as a result of the new development. | |

| Transportation Utility Fees | Transportation Utility Fees | Fees paid by property owners or building occupants to a municipality based on estimated use of the transportation system. |

| Special Taxes and Fees | Special Assessment Districts | Fees charged on property owners within a designated district whose properties are the primary beneficiaries of an infrastructure improvement. |

| Business Improvement Districts | Fees or levies charged on businesses within a designated district to fund or finance projects or services within the district's boundaries. | |

| Land Value Taxes | Split tax rates, where a higher tax rate is imposed on land than on buildings. | |

| Sales Tax Districts | Additional sales taxes levied on all transactions or purchases in a designated area that benefits from an infrastructure improvement. | |

| Tax Increment Financing | Tax Increment Financing | Charges that capture incremental property tax value increases from an investment in a designated district to fund or finance the investment. |

| Joint Development | At-grade Joint Development | Projects that occur within the existing development rights of a transportation project. |

| Above-grade Joint Development | Projects that involve the transfer of air rights, which are development rights above or below transportation infrastructure. | |

| Utility Joint Development | Projects that take advantage of the synergies of broadband and other utilities with highway right-of-way. | |

| Naming Rights | Naming Rights | A transaction that involves an agency selling the rights to name infrastructure to a private company. |

| ARRA | American Recovery and Reinvestment Act |

|---|---|

| COG | Council of Governments |

| CRRMA | Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority |

| DOT | Department of Transportation |

| EDC | Every Day Counts |

| FHWA | Federal Highway Administration |

| HEP | Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty |

| JD | Joint Development |

| MPO | Metropolitan Planning Organization |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| ODOT | Ohio Department of Transportation |

| PGP | Property Group Partners |

| PID | Public Investment District |

| ROW | Right-of-way |

| SIB | State Infrastructure Bank |

| SIF | Street Impact Fee |

| SME | Subject Matter Expert |

| STIC | State Transportation Innovation Council |

| STIP | Statewide Transportation Improvement Program |

| TIF | Tax Increment Financing |

| TIRZ | Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone |

| TRZ | Transportation Reinvestment Zones |

| TTI | Texas Transportation Institute |

| TTI | Texas Transportation Institute |

| TxDOT | Texas Department of Transportation |

| VRF | Vehicle Registration Fee |