The following pages summarize the meeting sessions and activities, as outlined in the Meeting Agenda above. The first four sessions were presentations with some discussion; the next three were facilitated working sessions in which participants were given a task to complete.

Participant Introductions

The day began with introductions. Each attendee introduced him or herself and described any experience or general perspectives they had regarding practical design solutions, context-sensitive solutions, and the various tools used to define context.

During the introductions, it became clear that the participants possessed widely varied levels of experience and knowledge with practical design, practical solutions, and CSS:

Participants also reported the following challenges, interests, and questions:

Opening Remarks

Comments provided during the introductions were synthesized and set the stage for the workshop’s expectations. Participants were reminded that the planning process involves finding the best solution that meets all the competing needs to the greatest extent possible within the given limitations. It was also mentioned that the Connecting Washington projects provide opportunities to be creative and flexible in determining what the ultimate solution might be.

One theme for the workshop was communicated as “blowing away all the barriers.” Participants were asked to think about what elements and tools they would need to deliver the best possible solution for a project, fully addressing the context and circumstances. One example provided was WSDOT’s Basis of Design documents which are a great tool that allows for documentation of design decisions, so that they can be defended and explained later.

Comments shared from other DOTs on CSS and design considerations include:

Comments like these reflect a rigidness and inflexibility that prevent truly elegant solutions. The practical solutions framework is all about prioritizing flexibility. It’s about empowering engineers and designers to think freely and holistically during the design phase, apply their expertise and best judgment, and broaden the scope to allow new alternatives and solutions that go beyond a rigid, prescriptive solution. This approach leads to creative solutions that truly meet the needs of the project while meeting all the standard requirements. Flexibility has been a hot topic in design for nearly 20 years, but implementing it is another story. CSS is about encouraging engineers to think creatively, consider how all transportation modes operate holistically as a system, and design practical solutions that fully incorporate the complete context.

John Donahue, WSDOT, provided a short overview of the practical solutions approach and the history of the practical design manual. He explained the basic tenets of practical solutions, such as the expectations that a designer should look first at operational and demand management; that the results should benefit the system beyond the project; and that the solution should not compromise safety. Mr. Donohue explained that a practical solutions approach seeks to integrate the various needs of stakeholders as well as the context into which the project is being introduced. Mr. Donohue noted that the decisions reached through a practical solutions approach and the practical design manual should be performance-based and should focus on the needs of stakeholders.

Mr. Donohue also reminded the group that WSDOT is very focused and committed to robust community engagement and encourages multi-disciplinary collaborative decision making, and he positioned the workshop as an opportunity to learn about the many tools available for addressing context and reaching practical solutions.

George Merritt, FHWA, offered his perspective regarding the importance of, and emphasis on, performance measurement for FHWA going forward. He offered that Performance Measures may make project delivery more challenging, but that understanding context will help alleviate those challenges. On May 20, 2017, FHWA’s rulemaking on System Performance National Performance Management Measures took effect, except for certain portions of the final rule pertaining to the measure on the percent change in CO2 emissions generated by on-road mobile sources on the National Highway System (the GHG measure), which has been delayed indefinitely.[1] Excluding the GHG measure, the final rulemaking on national performance measures sets forth measures that State Departments of Transportation (DOTs) and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) will use to identify and track the following characteristics within their jurisdiction:

Mr. Merritt broadly explained the importance of understanding and defining context. When there is, a transportation need or performance gap, the contextual elements of the built and natural environment can offer clues explaining its cause, and subsequently help find a solution. He explained how changes in land use can influence whether a transportation facility can operate as initially designed. It is important to understand land use changes and how they impact the transportation system and its ability to meet the needs of many users. He noted that solutions don’t always need to originate from WSDOT—other State agencies and regional stakeholders can contribute and help determine an ideal solution. A critical principle of CSS and practical solutions is knowing how and where to reach out for information.

Because several of the participants were unfamiliar with practical solutions, and others had some misconceptions about it, the session concluded with a summary on what practical solutions are, what they aren’t, and the process for applying a practical solutions approach.

George Merritt from the FHWA resource center kicked off the session with the national perspective and the upcoming efforts on advancing performance based practical design. George pointed out one of the key drivers for pursuing performance based practical design is the lack of funding to meet all the demands on the transportation system. This is also the basis for WSDOT to pursue practical solutions. Both programs encourage the analysis of fundamental needs and put forth the concept of looking to operational, safety, and modal solutions to address those needs.

George put emphasis on FHWA’s direction that the transportation system should accommodate all users and modes. He spent some time discussing the use of the AASHTO “Green Book” and that while it is a set of standards, those standards should not become barriers. He encouraged participants to make design exceptions on every project, and to document them well. If the exceptions are based on Performance Measures with contextual benefits, then they should feel confident in making those exceptions.

George pointed to the new FHWA “Guide for Achieving Multimodal Networks” as an example resource encouraging state DOT’s to be more inclusive with their design decisions. The guide offers methods and best practices for incorporating new modal elements into a project to provide community benefits. He talked about the importance of community engagement and communication when tackling the issues of multi-modal solutions.

The importance of Performance Measures was discussed, along with their applicable tradeoffs. The discussion focused on getting good quantifiable data to understand the tradeoffs, while understanding that some data will be more qualitative in nature. The concepts of balancing high performance with other factors, particularly cost, was also discussed. WSDOT was advised to be prepared to answer questions regarding whether or not closing a performance gap by the last 20 or 25% is worth the additional expenditure.

A question was posed to the group about how to consider these additional modal elements on an interstate highway. This lead to a vigorous discussion of examples where other modal elements have been integrated into the interstate system, and how that decision was driven by the context. The group also recognized that it can be challenging to integrate multi-modal elements into the interstate system, because of the fundamental purpose for which the system was designed. Some helpful resources include FHWA’s updated highway design standards, www.fhwa.dot.gov/programadmin/standards.cfm and AASHTO’s publication, A Guide for Achieving Flexibility in Highway Design, 1st Edition.

Stakeholder Perspectives

This portion of the workshop focused on facilitators and attendees providing perspectives on using context in project decision making. Unfortunately, due to scheduling conflicts, non WSDOT stakeholders were not able to attend the workshop. Instead, facilitators shared their experiences as stakeholders on many transportation projects and context defining efforts.

Information was shared on stakeholder engagement strategies and the Pennsylvania and New Jersey Smart Transportation Guide was specifically referenced, which is a resource that Pennsylvania and New Jersey DOTs use for their stakeholder involvement efforts. It was mentioned that one of the biggest challenges to successful engagement was a lack of transparency.

Participants were reminded to involve stakeholders early in the process because they have vital information that WSDOT engineers and designers need to accurately define the project and the context. Stakeholders also have information that a model output can’t uncover, but that could explain a model output. The process of actively soliciting and using stakeholder insights is critical to successful projects.

Group Discussion

The facilitators initiated a peer-to-peer exchange and asked participants to share with the group their experiences with stakeholder engagement, and any interesting cases of stakeholder perspectives they could explain. From the discussion, some interesting information emerged. First, WSDOT doesn’t always need to lead the way in solving a problem. Sometimes other parties are better positioned to identify a solution. Another participant shared an experience with the public engagement process. The process was challenging at the beginning, but ultimately was successful due to the organizing agency shifting its attention and committing to work directly with the community and stakeholders to find a solution. This scenario of beginning a planning process without stakeholder engagement, meeting resistance or problems, and then restarting the process with greater stakeholder involvement, generated a lot of discussion and sharing of ideas.

The session was summarized with an emphasis on transparency and openness to ideas as important factors for facilitating successful engagement efforts. Engagement must start early, even if it is challenging, because it yields such valuable insight into the context and stakeholder perspectives, and can ultimately shape decisions for the better. Stakeholders aren’t only affected by projects—they have valuable information about how facilities and infrastructure are being used and how users view them. For example, local public works employees know the streets and understand the local network better than anyone—they have insight into the basic needs of local residents and businesses. They may know about specific safety issues. Talking to local stakeholders can reveal insight that a model would never find.

Transparency and Cooperation

Facilitators discussed lack of transparency among state DOTs in regards to how design decisions are reached. For example, a frequent issue encountered among communities is a desire to address traffic calming by constructing “road diets,” also known as right-sizing. However, it is important to help the communities understand challenges a state DOT faces in trying to meet numerous needs of a community as well as the considerations for incorporating design solutions that are context sensitive.

WSDOT could consider coaching communities during their project outreach to inform the public on how to effectively engage in the transportation decision-making process. Communities often need better guidance on how to work with and support DOTs in responding to community demands—for example, by addressing concerns of decision makers, making land use decisions and local grid connection projects to reduce pressure on the state highway system, and anticipating community questions. Helpful Federal resource include US DOT’s Every Place Counts Leadership Academy Transportation Toolkit (https://www.transportation.gov/leadershipacademy); and State resources include Pennsylvania and New Jersey DOT’s Smart Transportation Guide (specifically Chapters 3, 4, and 5, which are written directly to communities).

Conflict within a community is not technically the responsibility of a state DOT. However, when it lingers unresolved, it can complicate or delay project delivery. In such cases, WSDOT may need to intervene and consider the question: How do we, within our existing processes, (and using the Context Questions), find and even create opportunities to go out and help the community? Additionally, WSDOT could find opportunities to put some of the burden of decision making process back on the community.

Case Study: Idaho Transportation Department

A case study was shared involving the Idaho Transportation Department (ITD), where a project schedule was readjusted to accommodate the process of building community consensus around alternatives for a project design.

The schedule was adjusted in part when a city mayor asked ITD to make the downtown more pedestrian-oriented. ITD developed a proposed alternative, presented it to community, and received significant backlash. In response, ITD put the project on hold for three months, developed sketches of several possible options, and asked the mayor to vet the schemes with community members. The mayor successfully achieved consensus around one design and accepted responsibility for any subsequent dissatisfaction among the community.

This is a good example of how WSDOT might delegate relevant decision-making to communities, and avoid taking the heat for conflicts arising within a community.

Visualizations

Community members often lack the ability to accurately visualize a finished project—a shortcoming that can lead not only to misunderstandings, but also to infighting among constituents. Participants were informed of several high-quality rendered visualizations (examples in Figure 1) that can be an effective tool for helping community members reach agreement on a project scope.

Participant Experiences

WSDOT representatives in attendance shared some of their own experiences. Below are some excerpts from the shared experiences:

These example projects identified several common values: transparency, openness to ideas, supporting communities, and applying these values early in the process. Applying these principles early can be difficult, because sometimes a project begins when the scope has already been determined—however, it is still important to gather input and insight about the project context.

Participants participated in three working group sessions. The first involved generating and refining context identification questions. The second involved creating metrics for measuring performance against those questions. The final breakout session focused on generating action items for process change. Details on how these sessions evolved are shared below.

During this session, participants worked to develop and refine questions to help collect the information necessary for the design decision-making process; understand what information is needed; and understand how to solicit responses to the questions.

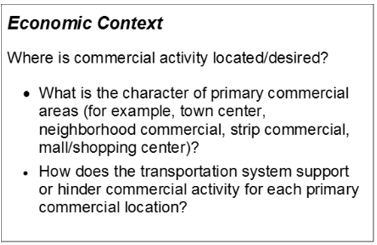

This facilitated discussion began with a series of “starter” questions—borrowed from NCHRP 8-68, Going the Distance Together: A Citizen’s Guide to Context Sensitive Solutions for Better Transportation Practitioners Guide—grouped into seven categories:

The full list of starter questions can be found in Appendix A. Many questions also included sub-questions. Figure 2 shows an example starter question and sub-questions. During the process of refining the questions, each participant was asked apply a green sticky note to questions they thought were applicable and helpful for determining context, and red sticky notes to indicate questions they considered not applicable. The facilitators then led a discussion among the group regarding why the participants did or did not like specific questions, and how the questions that were widely disliked could be improved to be more relevant. Discussing and analyzing this rationale was important to understanding motives, and ultimately relevant to context. Some of the concerns and points of contention are summarized below.

Following this discussion, participants were divided into six working groups and assigned one category of questions to each group. The groups were tasked with refining all the questions in their assigned category—editing questions, discarding questions they felt were unnecessary, and adding any additional questions that were needed. Each group posted its revised questions to onto the sticky wall (Figure 3). The participants all had a chance to review the questions and “vote” again with blue stickers (like) and red stickers (dislike).

Each group then each received a new set of questions and completed this task again. The edits, as well as the final questions, are listed in Appendix A.

Opening Remarks

A brief presentation on NCHRP 15-52: Developing a Context Sensitive Functional Classification System for More Flexibility in Geometric Design was provided during the opening remarks. The research objective of NCHRP 15-52 is to review the traditional functional classification scheme and revise it to include context and the potential impacts of the change on other areas of measurement. The report recommends five classifications, each based on contextual factors such as density, land use, and building forms. In addition, the new classification system provides information about serving multiple modes, user accommodations, and considerations for the whole network performance. The report is expected to be published by September 2017.

The research findings generated significant discussion. Participants were interested in how to consider the whole system beyond just a single project, and how to identify the benefits of that broader perspective on performance. WSDOT participants discussed the benefits of evaluating at the level of entire corridors, and being flexible when applying Performance Measures.

The topic of establishing Performance Measures based on the contextual-defining questions was introduced. The discussion began by providing FHWA’s definition of Performance Measures, taken from its performance-based practical design guidance. The process of developing Performance Measures began by asking four questions:

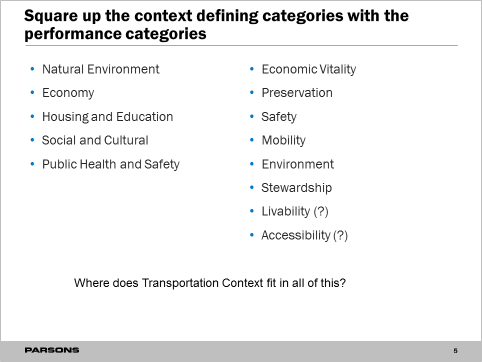

Six WSDOT performance categories were introduced and compared to the context categories from NCHRP 15-52, and those that were used in the context defining exercise so that the group could see the clear relationship between them (Figure 4). The key takeaway was that demonstrating excellence in the six WSDOT performance categories requires spending time defining the context, because performance and context are so closely linked.

Participants were presented with the baseline and contextual guidance in the WSDOT design manual and were invited to share any experiences they had working with the manual. Participants then discussed how Performance Measures can be used as a communication tool and a way to engage the community. The group discussed the scoping process as an elastic and iterative process that needs reevaluation as the project is defined and developed over time.

Identifying Performance Metrics

The participants were tasked with developing metrics for each of the questions developed during Working Session 1, as well as processes for monitoring performance with regards to the question during project execution and delivery. These Performance Metrics are also listed in Appendix A. Over the course of this exercise, the following discussion topics emerged.

After the groups presented their proposed metrics and had a chance to discuss each one, the facilitators led a discussion regarding the utilization of the metrics. Two questions emerged:

In closing, there was a discussion on the importance of understanding context for selecting the right measure and measurement. Participants generally understood that not all metrics will necessarily apply in all contexts, even similar ones. One participant proposed that planners should factor in future state conditions of land use and the implications for designs being developed now. Another participant asked how WSDOT can anticipate community concerns and be responsive to them. These questions and suggestions also raised another issue that had surfaced throughout the day, which was the need for more planning resources and comprehensive plan development. Without sufficient planning resources, WSDOT remains in a reactive mode and not close enough to these local or even regional planning efforts to be proactive and responsive.

The purpose of this working session was to generate ideas and next steps for process improvement. Participants were once again placed into working groups, where they brainstormed issues and actions that will require further attention in 2017. The results of this session are provided in in Appendices B, C, and D:

Appendix B lists the issues in order of votes received.

Appendix C aggregates the issues into overarching categories.

The predominant need expressed by the WSDOT representatives—in the final session discussion, in voting, and throughout the day—was to do a better job anticipating problems and issues earlier in the process. Project delivery would benefit from investing more resources, time, and process before a defined project scope is imposed on the project delivery process. Out of the 57 total votes cast for suggested process changes, 29 fell into the categories of scoping/early public engagement/better planning and data, reflecting the group’s focus on those early elements of the project development process.

Below is a complete listing of the process issues in which the WSDOT participants expressed interest. More detail can be found in Appendix C and in the “Recommendations to WSDOT” section, below.

Analyzing the six issues outlined above reveals that several of them are related. Participants considered better scope definition and community engagement important for resolving issues. Participants were reminded of the importance of conducting public involvement early in the process as opposed to waiting until the project design phase to fully engage citizens and reconciling perspectives of stakeholder groups. Facilitating public engagement early, during the initial scoping phrase, has the potential to yield better alignment with decision-makers.

Similarly, one way to achieve more consistency among regions and with headquarters would be to develop better Performance Metrics (again, early during planning and scoping) and track them throughout the project duration. This will tie back into the Context Questions and Performance Metrics.

[1] More information on the Final Performance Management Rule can be found at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/tpm/rule.cfm