U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-15-049 Date: April 2015 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-15-049 Date: April 2015 |

Credit: © Elenamiv/Shutterstock.com. |

Why read this report? For highway professionals the answer is obvious. This report is a treasure trove of information about pavements and their performance. But why should others read it? Because the report details how a long-term, strategically oriented research program was conceived, initiated, and successfully carried out. In the 1980s such research had disappeared from the transportation field, displaced by short-term efforts aimed at narrowly focused problem solving or policy adjustments. Such research is needed of course, but it cannot answer fundamental questions about the performance of transportation infrastructure—the very questions that the “infrastructure crisis” of the 1980s brought to the fore. Such questions require wellorganized, interconnected programs of research such as the Long-Term Pavement Performance program, better known as LTPP.

To understand LTPP, one must first understand the discontent and frustration among transportation agencies during the latter part of the 1970s and 1980s. Public works of all kinds seemed to be falling into disrepair at an alarming rate. The popular press dubbed it “the Infrastructure Crisis.” Roadways, especially roadway pavements, seemed to be most prominently afflicted.

Highway pavements, whether on country lanes or modern expressways, were simply not living up to the expectations of motorists and freight carriers. Nor were they living up to the expectations of the transportation agencies. No one was quite sure why this crisis arose or how it might be overcome. What was certain was that investments in highway research had fallen to a historic low. In the late 1970s, the U.S. Congress began to focus on the infrastructure crisis and the role of research in providing solutions. The key legislative action was the passage of the Surface Transportation and Uniform Relocation Assistance Act in 1987. This act significantly increased funds available for highway research and specifically funded a Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP) previously recommended by a select committee of the Transportation Research Board. A key element of SHRP was the studies of the LTPP program. These studies were explicitly designed to address concerns about the long-term behavior of highway pavements and how that behavior was influenced by climate, materials properties, traffic, design, construction, and maintenance.

The pages that follow recount the history and outcomes to date of the LTPP program. The program’s studies have tracked the performance of more than 2,500 pavement test sections located throughout the United States and Canada, in some cases for more than 20 years. What might not be evident in this history is how daunting a task it all seemed at the beginning, considering what was expected of the program.

LTPP was intended to be the largest pavement research effort ever—transcontinental in its scope. It was expected to involve the active collaboration of the transportation agencies of the 50 American States, Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia, and, ultimately, all 10 Canadian Provinces. The individual test sites would be widely dispersed, and the research teams would have to be masters of logistics. One part of LTPP would study the past and future performance of inservice test sections typical of pavements in current use. The second part of the effort would study specially constructed pavements where factors deemed important to pavement performance could be carefully controlled.

LTPP was expected to be truly “long term,” lasting at least 20 years. This expected longevity also posed a host of concerns about funding, continuity of the research, materials sample storage, data storage and access, and the like. Most of all, it required long-range research and management plans.

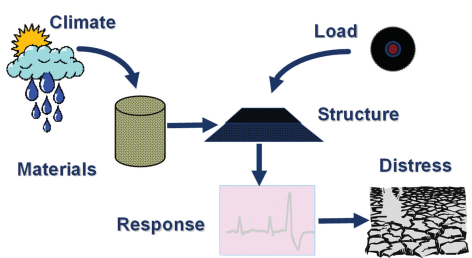

The studies were to be comprehensive, considering how variations in climate, materials, designs, maintenance activities, and other factors augment or limit pavement life. Also, a host of practical outcomes were

expected, including new, more reliable pavement design procedures and standards, cost allocation methodologies, improved pavement management techniques, and pavement maintenance policies.

These grand goals, grand expectations, and grand plans were seen as too grand by skeptics. They held that LTPP would wither before the studies were completed and would not meet the grand goals. Turn now to The Long-Term Pavement Performance Program and judge for yourself.

Neil F. Hawks

SHRP-LTPP Director, 1987–1992

A great deal of gratitude is owed those who gathered in the 1980s to not only discuss the condition of the Nation’s highway system but to also articulate a vision for its improvement and to develop a plan to make the vision a reality. Thus, the Long-Term Pavement Performance (LTPP) program came to be.

Thank you to the many authors of this history for taking time to record the facts about the program’s development so that future generations can have a good understanding of how the LTPP program began, has been managed, and has overcome the many challenges inherent in a long-term pavement monitoring effort. Staff members of the National Academy of Sciences’ Transportation Research Board (TRB) who work with the program are due thanks for helping to sustain the LTPP vision through the many changes in volunteer and staff participation over the years. The Federal Highway Administration’s Division Offices are also recognized for their role in maintaining communications between the LTPP program office and the highway agencies.

Acknowledgement is given to the many efforts and contributions of the LTPP program staff, its contractor staff, and the supporting TRB LTPP committees who have devoted countless hours to review the contents of this book for accuracy and completeness, and for providing the pictures displayed throughout the pages.

Leading the effort to assemble this book has been both a challenge and pleasure over the past several years. The primary goal for this document is to provide a detailed, written record of the LTPP program that serves the needs of different readers—from the chief engineer in the highway agency who wants a better understanding of the origins of the program (chapter 1) to the pavement engineer who wants to learn more about the different LTPP products (chapter 10) to the student who needs to know the different types of pavement performance data collected by the program (chapter 6). Thank you to management for the privilege of working on this assignment. Thank you to those who offered encouragement on those challenging days, but sincerest gratitude goes to the communications director who worked diligently to help resolve the big issues and tiniest details to complete this book. Read on, to learn about the LTPP program’s rich history and its future direction.

Deborah Walker

Research Civil Engineer, LTPP Team Member

Federal Highway Administration

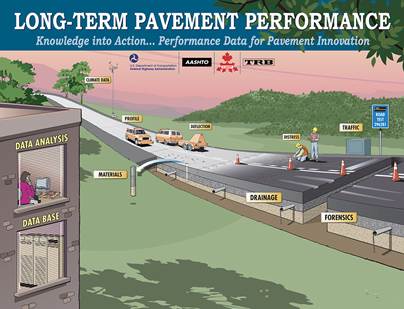

The Long-Term Pavement Performance program partners, data elements, and data collection, storage, and analysis activities. (Concept by Eric Weaver, Federal Highway Administration; executed by Jim Elmore, CSI.) |

The mission to study pavement performance systematically across the United States and to promote extended pavement life had been advanced since the late 1950s by the National Academy of Sciences’ Transportation Research Board, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, and the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). By the 1970s, deterioration of the highway systems built two and three decades earlier was a growing concern, and highway budgets were increasingly devoted to maintenance, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. By the 1980s, the bill coming due for pavement repair and replacement by the year 2000 was estimated at $400 billion.1,2 Highway agencies were creating pavement management programs to help them invest public funds more strategically, but lacked historical data to support those programs. Although many highway agencies were conducting pavement research, a broader, long-term, coordinated effort was needed to understand better how to design, build, and maintain long-lasting, high-performing pavements.

Congress, in the Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1978, directed the Secretary of Transportation, assisted by the Congressional Budget Office, to “investigate . . . the need for long-term or continuous monitoring of roadway deterioration to determine the relative damage attributable to traffic and environmental factors.”3 The Congressional Budget Office responded with Guidelines that outlined the effort needed:

Many of the uncertainties about pavement…can be unequivocally resolved only by carefully monitoring the volume and mix of traffic on selected roads over an extended period and by monitoring changes in the serviceability of the pavement over the same period. . . . This undertaking would also produce information that could improve practices followed in the construction and maintenance of pavement. The selection of the roads to be monitored should be made in such a way that the study will include a representative set of climatic and environmental conditions. In addition, it is important that a wide range of road types be monitored, including roads on every functional system and both urban and rural roads. To the greatest extent possible, wide variations in the mix of traffic should be sought at otherwise similar monitoring points, so that additional assessment of the relative effects of heavy and light vehicles can be made.4

|

The goal of the Long-Term Pavement Performance |

Nearly a decade later, with passage of the Surface Transportation and Uniform Relocation Assistance Act of 1987, Congress authorized the Long-Term Pavement Performance (LTPP) program as part of the first Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP), a 5-year applied research program funded by the 50 States through a dedicated share of the Highway Trust Fund.5 The program was joined by Canada, whose leaders were also seeking to advance highway research and were closely involved in planning for SHRP. Canada’s 10 Provincial highway agencies participated in SHRP and the LTPP program. The mission of the LTPP program was ambitious:

After extensive planning, data collection officially began in 1989. Four LTPP regional offices and a small national office were established to coordinate the collection of data within 17 scientifically designed experiments. Eventually, 2,509 pavement test sections on in-service highways were selected or constructed to address specific questions about how differently constructed and maintained pavements perform under the wide range of climatic, soil, and traffic conditions in the United States and Canada. Such an ambitious program required identifying the constituent materials and structural design of each test section and its maintenance history, monitoring weather conditions, determining traffic loads and volumes, and monitoring the resultant pavement performance. This vast store of information had to be carefully collected and safeguarded for future analysis.

At the end of SHRP in 1992, the LTPP program continued under the leadership of FHWA, and continues today, with the participation of highway agencies in all 50 States and 10 Canadian Provinces as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. Pavement test sections are monitored until they reach the end of their design life or are otherwise recommended to be taken out of study by the participating highway agency. By following these test sections over time, researchers are gaining insight into how and why pavements perform as they do, which provides valuable lessons on how to build and maintain longer lasting, more cost-effective pavements.

New experiments are being added to monitor the performance of pavement materials and technologies that were not yet in use when the LTPP program began, such as warm-mix asphalt and pavement preservation. As highway agencies implement other pavement materials and technologies, the LTPP program will consider whether they should be added to the program for long-term monitoring.

The LTPP program has generated a broad array of benefits across the pavement engineering and performance spectrum. Numerous applications now make use of LTPP data, and the utility of the data is increasing. LTPP benefits and products fit broadly within three categories:

Because of the foresight of leaders in the highway community three decades ago and the resolve of all parties involved in the program, LTPP-related findings continue to benefit the highway community and ultimately the taxpayers and driving public. In some cases, highway agencies have seen cost-savings in the millions of dollars on their highway systems as a result of these findings.

TYPES OF DATA COLLECTED AT LTPP TEST SECTIONS

The LTPP program continues to improve its data collection and quality control procedures through lessons learned and by adapting to changes in equipment and pavement technology. Although data collection and quality control procedures have varied over time, the principal data types collected since the beginning of the program, shown in the graphic above, have not. The program has collected these data in a consistent and systematic manner over the years, and they will be the primary source for evaluating pavement performance for the foreseeable future.6 |

To make the best use of the LTPP data, some understanding of the history of the program and the decisions that shaped it is needed. Many people and organizations have participated in this extraordinary data collection, analysis, and product development effort. Program decisions have evolved over time to implement what has been learned and to adopt advances in technology. This report was prepared to document the history of the LTPP program as a foundation for future work, to review lessons learned, and to consider how future pavement managers, researchers, and engineers can benefit further from the program. The report is organized in three parts:

I. Building and Managing the LTPP Program

Chapter 1. Origins of the LTPP Program—the program’s conception, pre-implementation studies, and early development.

Chapter 2. Management of the LTPP Program—the program’s organizational structure, peer review and advisory functions, and communication and coordination activities, and an introduction to the program’s managers.

Chapter 3. LTPP Program Partnerships—the major collaborators in the program and their contributions.

Chapter 4. Federal Investment in the LTPP Program—the U.S. Federal legislative mandates for the program, its budgetary support, and the impact of funding reductions on program activities.

II. Developing the Studies and the Pavement Performance Database

Chapter 5. Design and Recruitment of the LTPP Experiments—the planning process that determined what variables would be studied at the test sites that were to be chosen for the General Pavement Studies and constructed for the Specific Pavement Studies.

Chapter 6. Collection of the LTPP Data—data-gathering efforts, technologies, and procedures.

Chapter 7. Special LTPP Data Collection Efforts—data collected through special programs that were not in the original experiment designs—the Seasonal Monitoring Program, Traffic Data Collection Pooled-Fund Study, Materials Action Plan, and forensic studies.

Chapter 8. Storage, Growth, Security, and Dissemination of the LTPP Data—history of the data storage and distribution technologies and procedures.

Chapter 9. LTPP Data Quality Efforts—manual and automated quality control and assurance processes established to ensure that the data stored are of research quality.

III. Creating Products, Learning From the Past, and Preparing for the Future

Chapter 10. Turning LTPP Data Into Results—data analysis activities, LTPP products, research findings, and realized economic and performance benefits.

Chapter 11. Lessons Learned From the LTPP Program—lessons learned from some of the thornier problems that the program wrestled with, their outcomes, and insights gained.

Chapter 12. Paving the Way to the Future—preservation, refinement, and analysis activities required of the program to maximize the LTPP investment, and plans for monitoring the performance of new pavement materials and technologies.

Three appendices outline the program’s advisory bodies, technical contracts, and data collection equipment and software.

References are provided throughout this history, many with links to the World-Wide Web. Over time, these links may become obsolete. Readers seeking these source documents or more up-to-date information about the program and its future should refer to the LTPP home page and the LTPP InfoPave™ Web site.

REFERENCES

© Janis Knight, www.homeplanetimages.com |