U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-15-049 Date: April 2015 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-15-049 Date: April 2015 |

© Joseph Sohm/Shutterstock.com Some of the key lessons learned during the LTPP program may benefit future managers of the program and others who are pursuing long-term research goals. |

Through the process of planning the experiments and executing the data collection activities in the LTPP program, many lessons have been learned. While the technical research findings are interesting and useful, the lessons learned and observations along the way are equally interesting and potentially useful.

The task of the LTPP program managers has been to build and maintain a viable, reliable, and credible long-term research program that can provide highway agencies with the resources they need to better manage their aging roadways. These resources include the data and tools needed to develop better pavement design methods and maintenance and rehabilitation procedures. In the beginning, the LTPP program was not an “easy sell.” There were many obstacles as implementation began, and challenges continue to arise along the way. Although the problems have sometimes been painful to work through, valuable lessons have been learned by everyone in the program.

This chapter highlights some of the most pressing issues encountered since the LTPP program was authorized by Congress in 1987 and the ways in which these issues have been addressed while keeping in mind the goal and objectives established for the program.1,2 This written account presents some of the key lessons learned over the years with the hope that others planning short- or long-term research programs can benefit from these experiences.

One of the key elements to any successful program, short- or long-term, is preparation. The early LTPP program planners and managers provided a solid foundation on which to build the program. Their effort is evident not only in the longevity of the program, but also in how the program has contributed to the pavement community. The early planners, however, could not anticipate every challenge that would need to be addressed by the program's managers, partners, and contractor staff. Early assumptions were that selection of site locations would be relatively easily accomplished using highway agency information from as-built plans and pavement management systems. As implementation of the program began, the highway research community learned that we did not know nearly as much about the state of the pavements existing on the roadways as we thought we knew.

Although the idea of advance planning can be applied to each lesson discussed in this chapter, this section speaks to the issue of not having adequate information on which to proceed with implementation. Specifically, the program found that in some cases the basic design, construction, and maintenance information and other test section data needed to populate the LTPP database were unavailable or did not accurately reflect the characteristics of the test section.

When the program started, it was widely believed by the organizers that general information about the test sites proposed for the General Pavement Study experiments was readily available. Field visits and exploration of candidate project locations, however, showed that specific information about material types and properties, layer thicknesses, construction dates, traffic, and other test site details was difficult to obtain. Furthermore it was discovered that some plan sheets were not nearly as accurate as was expected. These findings resulted in shuffling sites between experiments or removing them from the program altogether.

© William Perugini/Shutterstock.com. “ You did then what you knew how to do. When you know better, you do better.” Attributed to Dr. Maya Angelou |

Although a body of knowledge did generally exist, it was usually scattered in various offices or divisions within the highway agency. The autonomy of many highway agency departments and divisions resulted in communication and coordination challenges in finding the historical data for the LTPP test sites. In some agencies, interaction between the district or field offices and the main office was limited, and project records were difficult to find. Often they were thought to be in transit, when they were actually stored in one place or the other, and no one really knew where to look. The LTPP program made a concerted effort to collect the missing data by working at times in the highway agency office reviewing plan sheets and inventory documents, and completing the necessary forms to include the data in the LTPP database. There are still some test sites where the historical data remain incomplete despite the program working closely with the agencies to collect this information.

Collection of climatic, materials, and performance time-history data was useful, but of limited impact if the progression of pavement condition could not be tied to the traffic loading. During planning, some major and grossly inaccurate assumptions were made in the traffic area.

First, it was assumed that wherever sites were selected, historical traffic information would be readily available. Second, since highway agencies routinely collected traffic data as part of their normal operations, it was assumed that they would be able to instrument the selected test sites to provide monitored data for future years. And, third, it was assumed that equipment would be available to accurately collect weigh-in-motion (WIM) data at a reasonable cost. As a result, little consideration was given to the need for traffic data during the site selection process. No consideration was given to the availability of historical information until after the fact. No consideration was given to the utilities and pavement conditions required for installation and proper operation of data collection equipment. These assumptions created a serious road block for the LTPP program until they were resolved by the traffic pooled-fund study (chapter 7), initiated following the Campaign for Program Improvement discussed below.

Those who managed the LTPP program and those who supported the program in its infancy understood that several years would be needed to develop data collection protocols, identify and test the data collection equipment, and build the database. All of these program activities were essential for the future development of useful and usable tools and products to address highway agencies’needs. The planners also knew that many years would need to pass before sufficient data were collected to produce any meaningful results. This inevitable delay was a problem because results were urgently needed by the highway agency partners.

The expectation that products would not be quickly available was not communicated to the highway agency partners early on and probably not often enough, resulting in misunderstandings and frustration. The LTPP program has since improved its communication with the highway agency partners by providing frequent program updates through its newsletter and Webinars. In addition, the program has performed and initiated data analysis studies that have the potential to address some of the pressing needs of the agencies, such as the study on effectiveness of maintenance and rehabilitation options.3 Many other examples are described in the data analysis and product descriptions in chapter 10. As monitoring continues on in-service pavement structures, more data are collected, and more analyses are conducted, additional knowledge, tools, and useful products will result to help the entire highway community.

The LTPP program requires a centralized management structure to effectively and efficiently perform the activities and functions of the program. The benefits from such a structure were first realized when the program was managed by the Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP) of the National Research Council in the early years, and since then by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Operating such a large program also requires collaboration among many partners in different types of organizations and among different levels of management, which both SHRP and FHWA have successfully supported. Direct communication and close coordination among multiple parties is only possible through a centralized management structure that can provide the funding and personnel resources needed to properly carry out the program’s many activities.

Efficient execution of a program such as LTPP requires considerable planning and a predictable, uninterrupted stream of funding. Given that highway bill funding usually lasts for a period of 4 to 5 years, and is renegotiated each time, the program has had to survive the passage of five highway bills over its more than 25 years of existence. With each new highway bill, LTPP program staff had to justify the value of the program and the logic of continuing its funding. Although the program has enjoyed continuous funding, there has been considerable disruption and uncertainty as to how much money would be available and when. In response to these situations, the program’s managers have learned to adjust its short- and long-term program plans and priorities, which are set based on multiple levels of possible funding. The reality, however, is that such funding uncertainties have led to missed opportunities in pavement performance monitoring and to the delay of critical activities such as correcting program weaknesses and addressing emerging pavement-engineering needs.

Central management of the LTPP program has provided the flexibility to strategically carry out the program activities during funding reductions. For any long-term research program, it is important to seek dedicated and uninterrupted funding.

The program has had the good fortune to have nearly the same core staff for much of its 25-plus years, which is extraordinary. The program, however, has seen its share of changes in leadership and staffing levels, resulting in changes in the approach to moving the program forward.

During the years when the LTPP study was part of SHRP, the challenge faced by the SHRP-LTPP management was finding the right “home” for the pavement research study where the work would continue after the SHRP program ended in 1992. Having a vested interest in long-term pavement monitoring well before the LTPP program was implemented, FHWA was identified as the most logical “home” for the program to live out its intended purpose. However, in more recent years given the uncertainty of the future of the LTPP program, the partners have feared that the program functions–particularly the housing of the database and the core program staff–would be dispersed across different offices within FHWA.

The highway agency and industry partners strongly voiced their concerns that decentralization of the LTPP program could result in neglect, lack of communication, the inability to properly manage critical activities remaining to be done, and a gradual loss of interest in the program itself.4 One such example can be shown in the transfer of LTPP product development from the core staff to another office within FHWA, which has left the program staff not knowing the status or delivery of products to the highway community. While efforts have been made to correct this problem, it is still a concern and not the ideal solution for the program. In response to the partners’concerns, FHWA management has committed to provide the staff required to fulfill the LTPP program’s needs.

The program’s history has shown that having a dedicated program staff provides coherency, close communication, and clear and firm control over priorities. Having the support of core staff through this centralized management structure, the LTPP program has been able to collect consistent, high-quality data. A case in point is the resolution of the Specific Pavement Studies (SPS) materials and traffic data gaps as discussed in chapter 7. SPS materials testing and traffic data collection were the responsibility of the individual highway agencies. The agencies made good faith efforts to discharge these responsibilities, but the dispersion of responsibility resulted in problems with timeliness, completeness, and consistency in the data provided. For this reason, efforts to correct the SPS materials and traffic data gaps were managed centrally and have successfully resulted in these data gaps being filled. Achieving consistent, high-quality data requires central management.

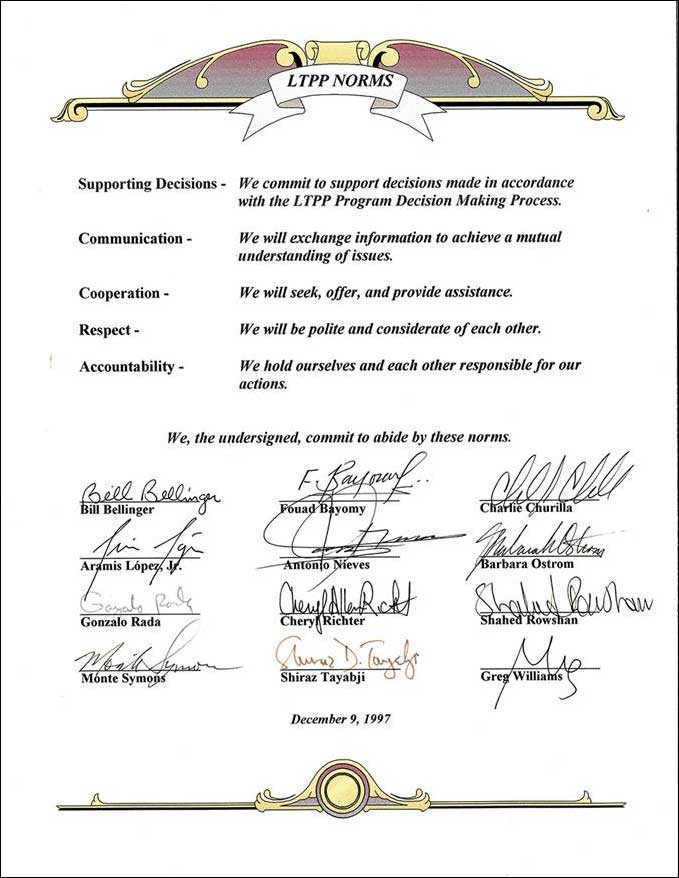

Having a dedicated staff to work on the LTPP program has been ideal, as demonstrated in the many accomplishments described in this report. The program’s staff, however, has not always been in agreement. Each staff person has had the best interest of the program in mind, but misunderstandings, disagreements, and frustrations have existed among members of the LTPP Team as would occur with any complex operation. In 1997, at an internal LTPP meeting, members of the LTPP program staff and its contractor and loaned staff discussed and positively resolved this issue by agreeing to operate under the “LTPP Norms” (see sidebar). This signed resolution by the parties emphasizes the importance of putting differences aside by being respectful and staying focused on moving forward. The resolution also shows the importance of people with different backgrounds, expertise, and interests coming together to work toward the good of the whole program. Synergy at its best was demonstrated by this group and has since continued within the LTPP program.

There were a number of meetings at the beginning of the program to inform participating highway agencies of plans and to solicit their support for activities. Given the support of highway agencies through the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) and the Transportation Association of Canada, senior management staff supported the program objectives, which trickled down to mid-level managers who provided their support as directed. Under SHRP-LTPP management, each highway agency was asked to provide an LTPP State Coordinator who would serve as the liaison between the agency and the LTPP program office. This practice continues under FHWA’s leadership.

Over time, agency personnel changed positions or left agency employment as a result of career moves and retirement. This attrition meant that those who supported the program at the outset were no longer available to encourage continued participation. LTPP program resources were continually required to educate those moving into positions of influence, and to encourage them to continue support for the program. The effect of attrition was especially felt in the solicitation of candidate projects for the SPS experiments. Participation in the SPS experiments, which involved new construction, was costly, and results were not to be realized for many years. Obtaining and maintaining enthusiastic support under these circumstances was extremely difficult.

Efforts to support the program were all voluntary, with agency staff already committed to performing their regular job duties, so it was often difficult for them to make time for the tedious and time-consuming tasks involved in researching available test sections for site selection, locating historical data, or planning construction of SPS projects. The LTPP program had its own way of doing things, with specific test protocols, design constraints suited to SPS construction, and data forms requiring detailed information about discrete points on the roadway where very little specific information existed. In order to fully support LTPP program activities, agencies had to make some adjustments to their normal operations. These changes were met at times with some resistance. As the program matured and the expectations of the highway agency were better defined, the LTPP program became a higher priority for the agency staff.

In addition, Federal funds for the program cover only part of its real cost, and highway agency staff and resources have been needed to assist in meeting the LTPP objectives. Some agencies have even allotted funding in their budgets to support LTPP program activities such as providing traffic control for data collection, materials sampling, or construction activities; installing instruments to measure traffic; and performing laboratory materials testing.

Since 1987, the LTPP program managers have been hard at work establishing the experiments, preparing for implementation of the program, identifying and collecting the right pavement performance data for future data analysis and product development, and developing a secure database to store the data. Given these and other key program activities, the program managers have learned to pause and reflect on the condition of the program and to identify what improvements can be and should be made. Such periodic assessments or reviews of the state of the program have happened through internal meetings, meetings with the program partners through the expert task group committee structure, and national meetings. This section focuses on the information gathered from key national meetings that have helped to make the LTPP program what it is.

Denver, Colorado (August 1990)

More than 400 invited representatives of highway agencies, industry, and research organizations gathered in Denver, Colorado, August 1–3, 1990, to take a close look at SHRP’s progress to date, and to suggest adjustments that would maximize the potential for delivery of immediately useful products when SHRP would end in 1992. The presentations looked at the strengths and weaknesses of current planning, and sought to gain input that would ensure that the LTPP program would remain in line with the stated goal and objectives. There was also a heightened awareness of international participation, as presentations provided input from international perspectives, and data analysis topics provided insight to the potential capabilities of the very early SHRP-LTPP data. The proceedings from this assessment meeting were published as SHRP Report No. 91-514, as a collection of the LTPP papers and presentations.5

Interviews at Eight State Highway Agency Offices (1995)

The AASHTO Task Force on SHRP Implementation provided valuable assistance to the LTPP program by making arrangements for the program manager at the time to meet with eight senior State officials (at least one from each of the AASHTO regions) in order to hear their pavement performance needs. The purpose of these discussions was to obtain guidance on the future direction of the program and to get an understanding of the States’expectations on the program deliverables.

The 1-hour, face-to-face meetings initiated by the LTPP program took place in 1995 in Arkansas, California, Kansas, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wisconsin. These senior State officials revealed that their active participation in the program was largely driven by their expectations that the tools and knowledge produced by the program would yield answers to and address issues such as the ones listed below:6

These thoughts strongly echo those cited in the “Blue Book”7 and “Brown Book,”8 but have a more tangible feel. In essence, the States want useful engineering tools and an enhanced knowledge base on which to base management and engineering decisions–their high-priority needs in terms of answers from the LTPP program. The program fell short of this expectation because initially the program was focused on data collection. Little effort was put on product development, which has had a negative impact on the program’s image. To understand why some pavements provide superior service beyond a 20-year design life, monitoring must be extended beyond 20 years, but States needed answers immediately. This posed a problem then and in some ways it still does now. Although many valuable data analysis studies have been performed by the LTPP program which have resulted in useful products (that would not have otherwise been developed) that have benefited the States and the broader highway community, there are still unanswered questions posed by the States that need resolution.

Irvine, California (March 1996)

The FHWA assumed stewardship of the LTPP program in 1992, when SHRP ended. Collection, management, and analysis of the data, and planning for continued operations moved seamlessly ahead during the transition from SHRP to FHWA.9 In recognition of the fact that the LTPP program was approaching the midpoint of planned pavement monitoring, it was prudent to plan a national meeting where participants could learn from those that had made use of the data collected to date, and provide input on any needed midcourse corrections.

The LTPP National Meeting was held at the TRB facilities in Irvine, California, March 26–28, 1996. This meeting drew participation from most highway agencies, industry, academic institutions, and FHWA. Presentations provided background information on the status of the various aspects of the program, and on results of data analyses. Breakout groups discussed program needs and high priority objectives.

Throughout the course of the meeting it was recognized that major gaps existed in the LTPP database, predominantly in traffic and materials test data. Those in attendance agreed that these critical data gaps must be filled if the program was to deliver on its stated objectives. It was also recognized that of the pavement types being studied, highway agencies were most interested in the result of rehabilitation studies, since the bulk of their construction efforts were in maintenance and rehabilitation of existing roadways. Concerns were expressed about studies focusing on pavement technologies and material types that were no longer used. All of these observations and many more provided strong feedback to the LTPP program managers, giving them much clearer direction as to what they should focus their efforts on.

In 1996, as the LTPP program was approaching the 10-year mark, FHWA decided to embark on an overall assessment to review the program goal and objectives, and to see in what direction the program was really heading. This assessment was accomplished by evaluating the impacts of deviations from the program’s plans, the number and types of test sections ultimately included for monitoring, data collection deficiencies, and resources. The ultimate objective of the assessment was to develop a revised strategic plan that focused on high-payoff products that would meet agencies’needs, improve program efficiency, and provide better quality data for product development.10

The assessment was conducted by a team composed of LTPP program and contractor staff, in concert with a special peer review subcommittee made up of highway agencies, TRB, and AASHTO representatives. In addition, through the TRB advisory mechanism, stakeholders in agencies were contacted to obtain input on agency needs as related to the goal and objectives of the program established 10 years earlier.

Early on in the assessment it became evident that data quantity issues overshadowed other program considerations. Specifically, large data gaps in the LTPP database and questions regarding the data were identified, which precluded addressing other issues such as data quality and test section coverage. In turn, this issue led to concerns about the ability of the LTPP program to fully deliver on its intended goal and objectives.

The Campaign for Program Improvement (1997–1999)

As a result of the assessment in which data completeness and data improvement were identified as the highest priorities for the LTPP program to address immediately, a highly publicized “Campaign for Program Improvement” (often referred to as the Program Improvement Campaign) was initiated in 1997 with support from the TRB LTPP Committee.11 This 2-year campaign consisted of five interrelated tracks of activities:

Special mention to the operations backlog track is given here since it was intended to address the gaps and questions regarding the data collected but not processed and entered into the LTPP database, which was identified as a major program issue during the assessment. Preliminary data resolution began in early 1998, and in April, when AASHTO passed a resolution seeking the agencies’help in resolving the LTPP data issues, the effort began in earnest.12 As a result of the AASHTO resolution, face-to-face meetings similar to the ones held with the senior State officials in 1995, were held but this time with each individual agency during the summer of 1998. In all, 60 meetings took place involving more than 1,200 highway agency and FHWA personnel. These meetings led to the development and endorsement of agency action plans, and implementation of these plans resolved many of the LTPP data issues.

The 2-year Program Improvement Campaign significantly improved the LTPP program's ability to better deliver on its goal and objectives through several accomplishments:

The LTPP program learned about its strengths and weaknesses as a result of the campaign and this resulted in a fundamental shift in program operations and management. The campaign aligned the program with modern quality management principles and practices, and it brought needed focus to product development and data analysis, as identified in the list above. However, despite its many accomplishments and successes, it is important to note that at the conclusion of the Program Improvement Campaign, data issues remained to be resolved. In particular, large data gaps remained in the LTPP database in terms of the SPS traffic and materials data, which necessitated the development and implementation of action plans. These action plans are discussed in the following section. The LTPP program has been proactive in its assessment of itself, and has continued to take steps to improve the manner in which the program is managed.

Major Data Resolution Initiatives

Due to budgetary restrictions early in the LTPP program, funding responsibility for traffic and materials data collection was assigned to the individual participating highway agencies. Although the highway agencies made a good faith effort to fulfill this responsibility at the LTPP test sites, problems of data quality and timely monitoring and testing arose. And while highly successful, the Program Improvement Campaign, which concluded in 1999, did not resolve these two major data issues that still existed at the SPS test sites. Consequently, in the early 2000s, the program undertook two major data resolution initiatives to address the traffic and materials data gap issues.

LTPP SPS Traffic Data Collection Pooled-Fund Study.

Traffic data collection within the LTPP program has always been a challenge, in large part because the associated technology has not lived up to the early expectation that it would be economically and technically feasible to install reliable WIM equipment at every LTPP test site. By the late 1990s it was clear that, as a consequence of mistaken assumptions about the availability of traffic data and the WIM equipment as described earlier in the chapter, traffic data were incomplete relative to original expectations. Complete, high-quality traffic data were available for some sites, while little or no traffic data were available for others. For the majority of LTPP test sites, traffic data availability fell somewhere in between.

Clearly, something had to be done with regard to the traffic data, particularly at the SPS projects, and it was. In response to the large SPS traffic data gap, the LTPP program, with support from the Expert Task Group (ETG) on LTPP Traffic Data Collection and Analysis, developed and implemented an action plan for closing the gap. Specifically, a pooled-fund study between the highway agencies and FHWA was initiated in 2001. The Long-Term Pavement Performance (LTPP) Specific Pavement Study (SPS) Traffic Data Collection Pooled-Fund Study, TPF-5(004), was designed to fill in existing data gaps and improve the quality and quantity of monitored traffic data for the SPS-1 (structural factors for flexible pavements), -2 (structural factors for rigid pavements), -5 (rehabilitation of asphalt concrete), -6 (rehabilitation of jointed Portland cement concrete), and -8 (environmental effects in the absence of heavy loads) projects. FHWA managed the study and oversaw the work of two independent contractors to resolve the traffic data gap. Although its implementation began later than anticipated due to various technical issues, in 2003 the traffic pooled-fund study began to generate the high-quality data needed to close the traffic data gap. At least five years of research quality traffic data were collected during the study for 28 of the 84 SPS projects and are available in the LTPP database.

The LTPP program made a significant financial contribution toward the pooled-fund study, but the bulk of the funding came from contributions by the highway agencies. A majority of the highway agencies with SPS projects (28 of 38) participated in the study, and some highway agencies with no SPS projects also contributed, essentially making their funds available for the good of all. The traffic pooled-fund study ended in December 2014, but the LTPP program has committed to continue collecting weight and classification data from as many of these projects as the budget will allow. As a result of this centralized data collection and review effort, a significant portion of the SPS traffic data gap was resolved, and the LTPP program is applying the methods from this initiative to collect traffic data at the new LTPP warm-mix asphalt projects. See chapter 7 for more information about the traffic pooled-fund study.

SPS Materials Action Plan.

SPS materials data were collected by the highway agencies according to materials sampling and testing guidelines developed by the LTPP program and site-specific sampling plans adapted by the LTPP regional support contractors working closely with each highway agency. The State and Provincial highway agencies took responsibility for sampling and testing the materials from their respective SPS projects, with two exceptions: the LTPP program performed the resilient modulus testing of unbound and hot-mix asphalt materials and the coefficient of thermal expansion testing for Portland cement concrete layers. Under this primarily decentralized approach, data collection practices were not consistent among the highway agencies. This inconsistency was in contrast to the materials sampling and testing for the General Pavement Studies test sections, where the LTPP program performed all of the associated activities with support from the highway agencies.

The program assessment revealed that nearly 48 percent of the required SPS materials test data were missing, which clearly limited the ability of the LTPP program to meet its goal and objectives. Starting in 2002, the program, with support from the ETG on LTPP Materials Data Collection and Analysis, began taking steps to address the SPS materials data gaps. This effort led to the further pursuit of missing materials data from the responsible highway agencies, the search for missing data at the LTPP regional support contractor offices, and the acceleration of hot-mix asphalt and unbound granular resilient modulus testing by the LTPP laboratory contractor. An SPS materials data resolution action plan was developed to provide standard procedures for collecting and testing the samples. This plan, known within the program as the SPS Materials Action Plan, was specific to the SPS-1, -2, -5, -6 and -8 projects and addressed three major areas:

A significant reduction in the missing SPS materials data, from 48 percent to 35 percent, resulted from the efforts started in 2002, but large materials data gaps still existed and they needed to be addressed. Therefore in 2004 the LTPP program, with the support of the Materials ETG, updated the action plan and began a concerted effort to resolve the remaining materials data gaps. The updated Materials Action Plan, implemented in 2004, called for nearly 10,000 laboratory material tests and included nine major tasks.

The quality of the SPS materials test data was also investigated to determine the need for repeating tests performed by the highway agencies as part of the final action plan. Major findings from this investigation were that (1) the biggest difficulty in assessing the quality of the SPS materials data is the lack of data; and (2) where data are available, the majority met the criteria used in the quality review. Accordingly, the decision was made that repeat testing was not necessary and therefore did not have to be included in the action plan. Despite the financial challenges faced by the LTPP program, in 2008, the program successfully resolved approximately 90 percent of the missing SPS materials data issues.13 See chapter 7 for more information about the SPS Materials Action Plan.

Newport, Rhode Island (April 2000)

On April 27, 2000, the LTPP program held a workshop in Newport, Rhode Island, to discuss the status of the program’s SPS-1, -2, -5, and -6 experiments. Nearly 150 participants were on hand to discuss the progress of these experiments, which were designed to explore how climate and cumulative traffic loading affect pavements of different compositions and cross sections. The LTPP contractor staff presented comparative studies on the performance of the test sections to date and the highway agencies presented their observations and opinions from the construction experience. There was active discussion about missing data, including traffic and materials information, and the critical need to obtain this information if the experiments were to be successful. The workshop provided yet another forum for the involvement of stakeholders in the program to voice opinions and observations, and to provide input for the planning and direction of LTPP program operations.

As discussed throughout this report, the LTPP program has benefitted from the close collaboration and collective efforts from different organizations, and also from the individual expertise from many individual professionals. Working in partnership with these organizations and professionals has always been integral to the program and began well before program implementation. However, during funding cuts that began in 1998, the partners became concerned that keeping them informed was no longer a high priority of the program staff. The budget constraints resulted from highway legistations passed in 1998 and 2005 (see chapter 4).

The budget provided by these legislations was not able to meet every need of the LTPP program. So, some tough decisions were made by the program based on the budget given. One such decision was to not only reduce the frequency of meetings with the ETGs and the LTPP Committee, but to also reduce the number of ETGs from six to two. So, instead of meeting every 6 months with six ETGs and the LTPP Committee to discuss the status and future work of the program, the LTPP Team began meeting annually with two ETGs and the LTPP Committee.

This was an uncomfortable time for both the LTPP program and the partners. Uncomfortable for the program because the managers thought they were making the right decisions at the time. Uncomfortable for the ETG and LTPP Committee members because they felt they were not being kept informed, and they were also frustrated that their input was not being sought to help in influencing the direction of the program, especially since the program was nearing the end of its planned 20-year data collection period. There was uncertainty as to whether or not the program would be extended beyond the 20 years even though hundreds of test sections still had not reached the end of their design life, and the LTPP database still needed to be further developed and maintained. It was vital that the partners through the LTPP Committee structure hear from the LTPP program what was being considered for the future and to be part of these discussions.

" There is a need for person to person communication, and for user involvement in technology transfer. The ways in which we do it are as important as important as doing it."

–Lynne Irwin, Cornell University14

As the LTPP Committee voiced their concerns, the LTPP program and FHWA’s senior management listened and made changes to correct the lack of communication between the program office and the partners.15,16 Since then, the semi-annual frequency of the face-to-face meetings has resumed. In addition, the LTPP Newsletter was established to keep the program partners informed during the time when meetings were not possible. The newsletter is still being distributed at regular intervals to hundreds of people across highway agencies, researchers, academia, and other interested parties.

The LTPP program knows that continued involvement of its stakeholders is vital to its ultimate success. Routine coordination and communication with participating highway agencies, for example, are of paramount importance-&–without their support, performance monitoring and other data collection activities on the LTPP test sections would not be possible.

The LTPP program has developed, written, and published thousands of formal and informal program documents over the years. The references cited in this very report show the magnitude and variety of communications produced and used by the program. The program staff has learned the importance of having a written account of the various decisions made, not only for those involved in working directly with the program but also for those who may want to learn about how the program is managed. To achieve high-quality data consistently throughout the United States and Canada, clear direction and guidance are needed by those collecting and processing the LTPP data. Having a written account of the program’s activities also provides future LTPP program managers and senior FHWA management with insight into the program. The permanent record of the program’s data collection procedures, calibration activities, and other important documentation used to manage the program will serve as valuable resources for the pavement industry for years to come. It is very important for any type of research program, long- or short-term, to have a plan to document its program along the way.

One of the frequent criticisms heard by the LTPP program managers was that the program studied “past” technology. The implication was that by the time sections were constructed and their performance had been monitored over a long period of time, the use of that material or construction technology would have evolved to the point where the findings were no longer appropriate to current practices. This potential problem is fundamental with a long-term study of any type. In the LTPP program, efforts were made to include a broad enough “inference space” of material properties and practices, such that results could be reasonably expected to reflect behaviors that would be encountered.

Another concern has been change in technology over time. Since the program began in 1987, there have been amazing advancements in electronics, equipment, and computing technologies. The program had to periodically update its pavement performance monitoring equipment and software as equipment became obsolete or worn out and as software was no longer supported. These changes each required updates in other areas and notifications in the resulting data to ensure that users were aware of the changes and their potential impacts on measurements. For example, the program has used four different pieces of equipment from three different vendors to collect longitudinal profile measurements. Although the end results should be the same, different electronic technologies and filtering techniques result in differences in the data. The LTPP program has conducted comparison and calibration activities for each equipment upgrade to minimize the impacts of such changes and noted the changes in the data set where appropriate to do so. In some cases, where equipment had not advanced to meet specific needs of the program, manufacturers adapted equipment to the program’s specifications.

Data processing and communications equipment and software were another area where continuous effort and investment are needed to keep pace with change. As the LTPP database is the program’s principal operational tool, its most strategic product, and its legacy to future generations of highway researchers and practitioners, a paramount program priority has been to keep the Information Management System secure and current with computing and communications software and hardware. Over 25 years, the program has moved from magnetic tapes and floppy disks to centralized data entry and data user access via the Internet to keep the data accessible. Equipment and software have been upgraded several times. Particular attention is directed to system security, and backups of the entire database are performed routinely (see chapter 8). Long-term research efforts must be prepared to adapt to a changing technological world.

Every chapter in this report tells part of the LTPP story. In this chapter, it was important to document some of the challenges so that others understand that the program has not done things perfectly or made the right decisions all the time; mistakes and adjustments have been made. Perhaps others will learn from what has been done, and appreciate the effort, hard work, and dedication of those who have made the program better with each lesson mentioned in this chapter, lessons that were not mentioned, and lessons that will come as the LTPP program looks forward to future research efforts, which are discussed in the final chapter.