This next portion of the study examines the viewpoints criterion, the third of the reasonableness criteria in the FHWA noise regulation in 23 CFR Part 772.

This examination is also a direct outcome of the research conducted in the first phase of this research as described in Evaluation of 23 CFR 772 for Opportunities to Streamline and Establish Programmatic Agreements[11]. That report addresses the identification of ways to streamline the requirements and procedural processes of the FHWA noise regulation and establish programmatic agreements between FHWA and SHAs. The report states:

"SHAs have adopted varying procedures for considering the viewpoints of the benefited property owners and residents. In many states, the property owner and renter are each allowed one vote. For multi-family land uses, the property owner is often allowed one vote per benefited unit.

"It is unclear whether these procedures fairly weigh viewpoints in communities with mixed land uses as well as rental communities. There is concern that some procedures could inadvertently result in one use/property having the power to dictate, through a majority of votes, whether a larger community desires a noise barrier."

The report noted that this topic of the viewpoints reasonableness criterion presented an opportunity for streamlining the process: "Additional guidance could be developed for assessing the viewpoints of the benefited property owners and residents, particularly in rental and mixed-use communities." The opportunity was assigned a "medium" priority in discussions with the project's Technical Working Group and was described as follows: "Evaluate methods for weighing the desires of property owners and residents in rental communities and mixed residential communities." The objective was to "[e]nsure viewpoints are considered fairly," and could lead to FHWA guidance to the SHAs and/or a change to 23 CFR 772.

Currently, Section 772.13 of 23 CFR 7772, Analysis of Noise Abatement, states the following:

A benefited receptor is one that receives at least a minimum specified noise reduction due to the abatement measure. The regulation requires that the SHA define the reduction required for a receptor to be considered benefited, and stipulates that the value cannot be less than 5 dB and no more than the Noise Reduction Design Goal criterion. As described earlier in this report, 44 of the SHAs have chosen 5 dB for the benefited noise reduction criterion, with four choosing 7 dB, three choosing 8 dB and one choosing 9 dB.

As with the other feasibility and reasonableness criteria for noise abatement, the SHAs are given flexibility in determining how the viewpoints of the benefited receptors are addressed. The one condition put upon the choice of factors in the criterion is that the viewpoints of both the property owners and the residents have to be considered for Activity Category B land uses. As with the feasibility and other reasonableness criteria described in the previous chapters of this report, there is a wide range in how SHAs have implemented these criteria in their noise policies.

At least two of the SHAs also extend consideration to beyond just those receptors that are benefited:

This report examines the range in values that SHAs have used for the different factors involved in the consideration of viewpoints. A detailed review was conducted of all of the SHA noise policies. The text from each SHA's noise policy on the viewpoints criteria is included alphabetically by state in Appendix A. After this examination, six SHAs' policies on the consideration of viewpoints are studied in more detail, based on discussions with the SHAs' representatives.

The factors to be examined are:

Before proceeding with the examination of the above factors, an example will illustrate how different decisions on reasonableness can be achieved for even just a single set of factors for a viewpoints criterion, simply by changes in the voting.

This example of how voting participation affects reasonableness decisions is taken from Evaluation of 23 CFR 772 for Opportunities to Streamline and Establish Programmatic Agreements. It consists of a mixed-use residential development that includes both single-family residences and apartments immediately adjacent to a Type I highway project, as shown in Figure 25. A barrier to protect the single-family residences would have to extend a substantial distance past the apartments and vice versa. It is assumed that the barrier would benefit 60 apartments and 20 single-family residences. It is also assumed that the apartments are owned by a single owner.

For the sake of illustration, it is also assumed that the SHA noise policy requires that a simple majority of benefited property owners and residents, based on the votes received, need to vote in favor of the barrier for it to be reasonable. The policy states that votes are to be assigned as follows:

Thus, there is a total of 140 possible votes.

Table 28 presents five cases of different voting results. The last two cases differ from the first three in that they assume that only the apartments exist (120 possible votes).

Case 1 assumes that all single-family homes are owner-occupied and that all owners and residents cast ballots. Thus, 140 votes were cast. This scenario is very unlikely and is presented to compare and contrast results for mixed-use communities. In this case, as shown in Table 28, the apartment owner and the apartment residents would each have 43% of the vote (60/140 each, for a total of 120/140), while the owners of the single-family residences would have only 14% of the vote (20/140).

If all of the residents, both in the apartments and the single-family residences (57% of the vote) voted in favor of the barrier, then the barrier would be reasonable. The viewpoint of the apartment owner, while considered, would not dictate the reasonableness determination.

However, voting responses for apartment residents are typically much lower than responses for owner-occupied single-family homes. Case 2 in Table 28 assumes that votes are cast by only half (30) of the apartment residents, for a total of 110 votes cast. In this case, the apartment owner controls 55% of the vote compared to 27% for the apartment residents and 18% for the single-family homeowners. If the apartment owner opposes the barrier, the barrier would not be reasonable even if 100% of the residents who voted, including all of the homeowners, were in favor of the barrier.

Additionally, rental communities are often not fully occupied, so some benefited apartments may be vacant. In these cases, there would be only one vote for each vacant unit, which would belong to the property owner. As a result, the apartment owner would have more votes than the apartment residents.

Case 3 in Table 28 assumes that the apartments are 60% occupied, and only 25% of the apartment residents cast votes (60 x 60% x 25% = 9 votes cast). In this case, the apartment owner controls 67% of the vote compared to 10% for the apartment residents and 23% for the single-family homeowners. As with Case 2, the barrier would not be reasonable if the apartment owner opposes it, even if all of the residents who voted where in favor.

Case 4 assumes that the apartments are the only residential units in the area ("stand-alone"), for a total of 120 possible votes. If the apartment owner and all apartment residents cast votes, then each would control 50% of the vote. There would be no majority and a reasonableness determination could not be made if the owner and all of the residents disagreed. If the policy, however, said that 50% or more of the cast votes had to be in favor, instead of a majority, the barrier would be reasonable in terms of the viewpoints.

Case 5 assumes that the apartments are stand-alone (120 possible votes) and 80% occupied. In this case, the apartment owner controls 56% of the vote compared to 44% for the apartment residents, so the viewpoint of the apartment owner would dictate whether the barrier is reasonable, regardless of the voting of the apartment dwellers.

Case 5 also illustrates that, if the criterion is simple majority of all votes with equal weighting to the votes of all renters and all dwelling unit owners (in this case the apartment complex owner for all units), the viewpoint of the property owner will always dictate the reasonableness determination for stand-alone rental communities as long as one of the benefited units is vacant or one renter does not vote. As noted in Evaluation of 23 CFR 772 for Opportunities to Streamline and Establish Programmatic Agreements:

"Whether this is an equitable situation is a point of debate. The owner has a significant financial investment in the property. Rental populations can be transient and tenants might have alternative housing options with lower sound levels. However, there are communities where tenants may be long-term and have a vested interest in their community. While weighing the owner's desires more heavily might seem fair, the residents live with the noise environment so it is reasonable that their viewpoint be considered as well."

As noted before the above example, there are two main philosophies by which the voting is interpreted. In the first instance, a barrier is judged to be reasonable if a certain percentage of the benefited receptors vote in favor of it. In the second instance, the barrier is deemed to be not reasonable if a certain percentage of the benefited receptors vote against it. In the former case, the benefited property owners and residents have to take positive action to demonstrate their desire for the barrier. In the latter case, it is presumed that the barrier is desired unless the needed number or percentage of benefited property owners and residents take action to reject it.

Under both philosophies, some SHAs base their decisions on only the actual number of votes or responses that they receive. Alternatively, some SHAs base their decisions on a needed percentage of all of the possible votes whether or not a formal response is received. Then, there are some SHAs that are not specific in their policies as to whether a decision is based on the percentage of those voting or a percentage of all possible votes. A follow-up inquiry was done for some of those SHAs that do not define what the percentage is based upon and is reflected in this discussion.

Different decisions can easily be reached on reasonableness depending on whether the percentage is based on votes received or all possible votes, with the latter being the more difficult to achieve criterion. Table 29 shows the breakdown by these different philosophies and factors for the 52 SHA policies (50 states plus the District of Columbia and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico).

*A non-vote counts as being in favor of the abatement measure.

Basically, 32 SHAs require a positive vote in favor. Thirteen SHAs require a negative vote against, five state the requirement both ways, and two use percentages to express a degree of reasonableness.

Table 30 lists the SHAs that base their decisions on a percentage of the votes received that are in favor of the barrier.

As shown in Table 30, 15 of the 22 SHAs that use the percentage of votes received require half or a simple majority of the votes for the barrier to be deemed reasonable. The other seven SHAs require a range of 60% to 80% of the votes received to be in favor of the barrier. For several SHAs, there are further conditions. For example:

The more stringent criterion for a positive decision on reasonableness can be when the needed percentage of votes is defined as being of all of the possible votes, not just of the received votes, unless the non-votes are considered to be in favor of abatement. Six of the seven SHAs (listed in the second row of Table 29) require 50% or a simple majority of all possible votes to be in favor of the barrier for it to be considered reasonable (see Table 31); Massachusetts requires 67%. In the voting process, Arkansas gives an owner-occupant a full vote and nonresident owners and renters 0.5 votes each, while New Hampshire gives an owner-occupant two votes and nonresident owners and renters one vote each.

Idaho's policy requires 50% plus one of the benefited owners, except in the case of a multi-unit rental property (including a mobile home park) where if the owner of the property is opposed to the barrier, a 75% positive vote of the benefited renters would result in a favorable decision, overriding the owner's vote.

Two of the SHAs - Michigan and Massachusetts - are much less stringent than the others because non-votes count in favor of the abatement measure. For example, the Michigan policy states: "The absence of returned surveys or attendees to public meeting may be considered as an affirmative vote for noise abatement."

*For a multi-unit rental property (including a mobile home park), a 75% positive vote of the benefited renters would override an owner's negative vote.

**A non-vote counts as being in favor of the abatement measure.

Three SHAs do not indicate in their policies if the percentage of positive votes is of the votes received or of all possible votes:

For the seven SHAs in Table 29 that require a certain percentage of the received votes to be negative in order for a barrier to be not reasonable, six require a simple majority. As an example, Delaware's policy states: "In considering the receptor viewpoint, only an explicit "no" to noise barrier construction will be considered as opposing the construction of a noise barrier." One of those six - Tennessee - qualifies its percentage as 51% of the impacted and benefited receptors needing to vote against the barrier.

The one exception in this group of SHAs is Arizona, which requires a "substantial portion" of the votes to be against the barrier for it to be determined to be not reasonable, without defining "substantial."

Washington State offers an interesting perspective on the interpretation of its policy. According to J. Laughlin of WSDOT, the DOT tries to get as many of the benefitted property owners and residents engaged as possible (e.g., by holding meetings, conducting mailings, giving presentations of what the noise wall would look like, and working with community leaders and representatives). WSDOT may treat each decision on a case-by-case basis, and if it feels that there is sufficient representation of the community responding, it could consider the majority of all who responded. For example, if only 3 people out of 20 residents responded (with two opposed and one in favor), WSDOT would not consider non-votes to be "Yes" votes and would only consider those who responded (i.e., the 67% opposed); however, with such a low response the poll would probably be considered as a failed poll and WSDOT would try to engage the community again, perhaps with a second meeting and poll. If they still felt they did not get enough respondents, they would likely proceed with building the wall even thought there was a majority in opposition among the small number who voted.

Ultimately, Mr. Laughlin noted, the decision rests with the DOT. WSDOT is only considering the neighbors' opinion, but it considers other factors as well, for example: the lowering of property values caused by blocking the view, if the sound levels will be high (in the mid to upper 70 dBA range, for example), and how often people move in and out of the neighborhood. WSDOT also weights the first row residents' opinions more than those of second row residents. They have had instances where the second row wants the wall but the first row does not because of their view.

Five of the six SHAs in this category require a simple majority of all of the possible votes to be against the barrier for it to be considered not reasonable (Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, North Carolina and South Carolina). Maryland's policy further qualifies the vote by saying "A vote tally of more than 50% AGAINST the proposed noise abatement is required for the barrier measure to be rejected as long as no single individual or entity is responsible for all the negative votes." [italics added]. It goes on to say it "will not consider the percentage requirement met if all negative votes were cast by a single individual or entity. The only exception to this rule shall apply in the case where there is only a single individual or entity eligible to vote." The sixth SHA - Maine - says in its policy that the barrier "will not be considered reasonable if fewer than 75% of the benefitted receptors approve of the construction of a noise barrier." In effect, its policy says that the barrier will be considered not reasonable if 25% or more vote against it.

Nevada's policy states that noise barriers "will be constructed as modeled and designed unless the benefitted receptors are opposed to their construction." The policy then specifically addresses non-votes: "If a response is not received from a valid benefitted receptor, it will be recorded as being in agreement with and supporting the proposed traffic noise abatement measure." Similarly, in South Carolina, its voting material explains that a non-response is counted as a supporting vote for the abatement measure, according to H. Robbins of South Carolina DOT,

Five SHAs listed in Table 29 give percentages of votes for a barrier to be considered reasonable as well as for the barrier to be considered not reasonable. In all five cases, a simple majority of the votes is stated as being needed to be in favor of the barrier or to be opposed to the barrier.

Finally, two SHAs, Mississippi and West Virginia, use identical systems for determining the degree of reasonableness, based on the percentage of benefited receptors wanting the barrier. Neither states if the percentage is of the votes received or of all possible votes. Both SHAs state that "the construction of a noise barrier is not reasonable unless a majority of residents and property owners of the benefited receptors…want a noise barrier." The vote is qualified as follows:

As noted above, an important factor in determining the percentages is how the non-respondents are counted. Seven SHAs address this situation in their policies:

Two others provided information not stated in their policies:

Another important determinant in the reasonableness decision is whether a certain percentage of the benefited receptors are required to vote in order for the overall balloting to be considered valid. Six states include a required percentage of the eligible voters. Two of them specifically say that the barrier will be considered not reasonable if the rate is not achieved, while the other four do not rule out moving forward with the barrier:

Utah's policy is unique in also giving votes to "receptors that border and are directly adjacent to the end of a proposed noise wall that are not, by definition, benefited by the wall."

A follow-up with R. Bales of Indiana DOT revealed that if the DOT does not get a 50% rate, then the decision is a project management decision, citing an example where only 48% responded to the survey with a large majority of that 48% being in favor of the barrier. In such a case, Indiana DOT may continue its outreach to secure the number, such as by contacting property owners by phone or visiting the residence.

Four SHA policies have a desired response rate but do not require a certain response rate for the vote to be considered valid:

In an attempt to obtain as many votes as possible, some SHAs, as just noted above, will make multiple contacts with the benefited receptors if they do not receive an initial response. Fifteen SHAs give some indication in their policies of the number of contacts that they will make, as described below.

Missouri's policy says that it will contact the benefited receptors once. Missouri notes on its Official Ballot:

"This is your one and only chance to vote. You will not have this opportunity again, so please take the time to vote now. One (1) vote will be counted per residence. If a ballot is not returned, it will not count. In order for your vote to count, please have it post-marked by (date). You are welcome to return the ballot in person at the resident meeting on (date). Ballots post-marked after (date), or ballots not returned at all, will not count in the final decision."

Louisiana's policy indicates that it will contact the benefited receptors if opposition to the barrier is raised during the public involvement process: "If no relevant objections to the proposed noise abatement are made at this level of public involvement, this [Consideration of Viewpoints] criterion is deemed met and abatement considered reasonable from the viewpoint of benefited receptors. If relevant objections are identified, a follow-up solicitation will occur with property owners and residents of the benefited receptors."

Colorado's policy notes that "At a minimum, one attempt to contact each identified benefited receptor site (both property owner and resident…) must be made and documented."

Tennessee's policy indicates that "The input of the benefited property owners and residents will generally be received at planning, NEPA or design public hearings or public meetings. Input received at these hearings or meetings may be supplemented, as necessary, with formal survey methods on a case-by-case basis as discussed in the TEPM[12]. TDOT will conclude that a community desires the construction of a noise barrier unless a majority (at least 51%) of the benefited property owners and residents indicate that they do not want the proposed noise barrier."

Arkansas' policy indicates that the "input of the benefited property owners and residents will generally be received at planning, NEPA or design public hearings or public meetings. Input received at these hearings or meetings may be supplemented, as necessary, with formal survey methods on a case-by-case basis."

Seven SHAs indicated that they would contact the benefited receptors twice:

Four more SHA policies give other indications regarding the number of contacts:

While not stated in its policy, Massachusetts' ballot indicates that its decision will be based on the initial responses to its balloting, with no follow-up for unsubmitted ballots. In contrast, Washington State will follow up on low response rates even though its policy is silent on that follow-up.

In addition to the voting in favor or against the barrier, four SHAs' policies describe how the benefited receivers also provide input or vote on their aesthetic preferences for the barriers:

Other SHAs that obtain input on color and/or texture, although not stated in their policy, include: Tennessee, Arkansas and Massachusetts.

The weighting of votes for the various stakeholders is the factor that has, by far, the greatest variation in values used by the SHAs.

Seventeen SHAs simply state that the views of the benefited "property owners and residents" [13] will be obtained, without giving any indication of any weighting of the votes assigned to these two cohorts.

Beyond that simple definition of the stakeholders, the assignment of votes or points on a ballot increases in complexity. One differentiation is between owner and renter, in which case the owner is a nonresident owner. Another differentiation is between property owner and resident. In this case, the resident may by the owner (owner-occupant) or a renter. As described in more detail below, some SHAs thus specifically give votes to owners and also to residents. Others specify votes or points for owners living off-site and for their tenants or renters.

Some policies give one vote to an owner-occupied dwelling, and one vote each to both an off-site dwelling owner and the dwelling tenant, resulting in a rental property having twice as many votes as an owner-occupied property. Others split votes on rental units between the owner and the renter so that a rental unit receives the same number of votes as an owner-occupied unit.

Some specify a vote weighting for multi-unit complexes such as apartments, condominiums, and mobile home parks in addition to single-family residence rental units. One SHA gives the owner of a multi-unit complex a single vote and gives the tenants one collective vote. Others give the owner a vote for every rental unit and each tenant gets a vote for each unit. Others specify how to weigh mobile home or trailer parks.

One SHA discounts the vote of an owner of a rental property by 50% if the renter of the property votes differently than the owner. One SHA obtains ballots from both owners and residents but only counts the owner votes toward the decision on reasonableness.

Other SHAs give additional votes or use multipliers if a benefited receptor is: 1) in the "first" or "front" row adjacent to the highway (or abuts the ROW), or 2) is both impacted and benefited. Another gives extra points based on the amount of noise reduction to be provided by the barrier.

The SHA policies have been analyzed in two groups:

The results are presented in a separate table for each grouping. Since the phrasings used in the policies vary, these tables interpret those phrasings with a common terminology. A discussion follows after each table.

Table 32 summarizes the weighting of votes for owner-occupied properties and rental properties where there are no additional weighting factors by row away from the road or by impact condition.

There are 39 policies in this table. As noted above, 17 of these 39 SHA policies simply state that the views of the benefited "property owners and residents" will be considered. This phrasing duplicates the phrasing used in 23 CFR 772: "consideration of the viewpoints of the property owners and residents of the benefited receptors."

The presumption, not stated and possibly not true for each SHA, is that every property owner would get a vote whether living in the dwelling or living elsewhere and the resident would get a vote, whether that resident was the owner or a renter. This assignment would mean that owner-occupied residences and rental units would each get two votes, with the rental unit vote split out as one for the nonresident owner and one for the renter.

An alternative interpretation could be that an owner-occupied residence would get one vote (for the owner who is also the occupant) and two for a rental unit (one for the nonresident owner and one for the renter).

Only two of the 17 policies gave some indication of their intentions:

Nevada's policy is also unique in that it gives extra points in the voting based on the amount of noise reduction to be provided by the barrier to benefited receptors: 3 points for 7 or more dB of noise reduction, 2 points for 6 dB of noise reduction, and one point for 5 dB of noise reduction.

Aside from the 17 SHAs that do not distinguish between "property owners and residents", Table 32 shows that:

Of the ten policies that give equal weight to owner-occupied and rental properties, six give each unit one vote (Arkansas, California, Florida, Missouri, Texas and Puerto Rico), and four give each unit two votes (Georgia, Kansas, New Hampshire, and South Carolina).

New Hampshire's language helps clarify confusion that may arise over nomenclature regarding owners, residents and renters. It refers to the resident's vote as an "occupancy" vote: "One owner and one occupancy point will be given for each receptor." Thus, both rental and non-rental properties get two points (i.e., two votes).

For these ten policies that give equal weight to owner-occupied and rental properties,

Florida and California split the vote between a nonresident owner and renter on a 90%/10% basis, but in different manners. For Florida, 0.9 of each rental unit vote goes to the owner and 0.1 votes of each unit go to the renter. Thus, in a ten-unit apartment, the owner would have 9 votes and the renters would have, collectively, one vote. Florida also uses a similar division for a mobile home park with an 80%/20% split between the mobile home park owner and the mobile home residents. For California, the owner gets 0.9 of a single vote and the renters each get 0.1 of a vote per unit. Thus, 10 renters could outvote one owner.

Missouri's policy states that the viewpoints of residents will be evaluated as a portion of an aggregate of 25% of the total. The viewpoints of the owners will be evaluated as a portion of an aggregate of 75% of the total.

Texas obtains ballots from both owners and residents but only counts the owner votes toward the decision on reasonableness, noting that "ballots cast by residents will be obtained for viewpoints."

As noted above, eleven policies give more weight to rental properties than owner-occupied properties:

Oregon's policy contains one of the most detailed descriptions of the vote weighting. In addition to the above specifications for multi-unit complexes, it assigns votes as follows:

Oregon's policy also indicates that for the apartment and condominium renters, the collective vote of "yes" or "no" is determined after all of the individual votes are tallied.

Idaho's policy is unique in its approach when the owner of a group of rental units is opposed to a barrier. Its policy states: "75% of benefited renters must approve a noise barrier" to override an owner who is against the barrier, giving this example: "…if the owner of a Mobile Home Court does not want a noise wall, then benefited renters would be polled to determine their view. If 75% or more wanted the wall, the wall would be considered desirable."

Table 33 and Table 34 summarize the weighting of votes for owner-occupied properties and rental properties in the 13 SHA policies where there are additional weighting factors for "first-row" (or "front-row") or by impact condition.

Ten SHA's policies give extra weight for a receptor being on the front row (first-row), with Minnesota using the term "abutting the highway" instead of being on the front row.

Five of these policies give only the owner additional points for being a front-row or first-row benefited receptor, not the renter. They also give the same number of points to a receptor regardless if it is owner-occupied or a rental unit.

Nebraska assigns up to four votes per dwelling unit: 1 for being a resident, 1 for being an owner; 1 for being the owner of a front-row residence, and 1 if the owner of a front-row dwelling unit also lives there. Thus, it gives a total of 4 points for a front-row owner-occupied dwelling unit. It gives 2 points for an owner occupant not in the first row (1 for being an owner and 1 for being a resident).

Three of the policies give both the owner and renter additional points for being a front-row or first-row benefited receptor.

Washington State also weights the first row residents' opinions more than those of second row residents and reports that there have been instances where the second row wants the wall but the first row does not because of their view. Washington State gives a nonresident owner 1.5 points if on the first row and 1 point if on another row. It will then reduce those votes by 50% (to 0.75 and 0.5) if the renter of the unit disagrees with the owner's vote: "If eligible receiver locations are not owner-occupied, the opinions of both the renter and property owner shall be considered. When the two opinions differ, the renter's opinion shall reduce the weight of the property owner's response for that unit by one-half. When polling responses are not received from the renter, the property owner's vote will represent the voting unit." Washington State does not give the renter a specific number of votes.

Three SHA policies assign extra votes for benefited receptors that are also impacted:

The SHA policies indicate that they use a variety of methods for obtaining the viewpoints of the benefited receptors, including:

Table 35 indicates the number of SHAs stating that they would use one or more of these techniques.

Of the 34 SHAs that use mailed questionnaires or surveys, seven send these out by certified mail (District of Columba, Georgia, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, Washington State, and Virginia (which states that certified mail is preferred for the first contact)). Three states indicate that they use registered mail (California, Wisconsin and Utah (for its second ballot)). Maine requires the use of certified or registered mail.

All 23 of the SHAs that use public involvement activities such as meetings and workshops also use mailed questionnaires, surveys or information packets as part of their process. Many specify timelines regarding when mailings take place relative to meeting dates, when ballots are due and final voting deadlines.

Thirteen SHAs do not specify any technique, although one of them, Nevada, does say that the responses must be in writing.

The "other" outreach techniques are unspecified by the SHAs, but are described with terms such as: defensible, targeted, reliable, and acceptable to FHWA and the Department.

Six SHAs were contacted and discussions held with their noise specialists to learn more about their experiences in implementing their Consideration of Viewpoints criterion. The SHAs are:

The following points provided a background for the discussions. Not every point was touched upon for each SHA:

NDOR Environmental Specialist, Will Packard, provided the information used to prepare this section, including the sample ballot and project graphics below. He is in charge of the NDOR noise and air quality program and was actively involved in the development of the NDOR noise policy.

The NDOR voting process has been implemented on a number of federal-aid Local Public Agency projects that are subject to the NDOR noise policy, including three in Omaha, NE and one in Lincoln, NE.

A standard voting timeline typically spans 45 days. Two weeks before a noise abatement stakeholder meeting on a proposed project, NDOR sends out an informational packet with a ballot. The stakeholders are then invited to attend the noise abatement meeting where a presentation is given on the project including a demonstration using an NDOR customized version of the FHWA Interactive Sound Information System software.

NDOR previously used a simple ballot for all stakeholders. NDOR has since developed a point system where each ballot is personally addressed and mailed to the owner and/or occupant of the benefited receptor, and shows the allotted number of points for that particular receptor on the ballot. The stakeholders are given two weeks after the noise abatement stakeholder meeting to submit their ballot and if ballots are not received a reminder is mailed out to them. They then have 15-days to respond before the voting is closed. Figure 26 shows a typical ballot.

One change in procedure that NDOR is considering is to not mail the ballots out with the informational package and announcement of the meeting. Some stakeholders submit the ballot before having had a chance to see the presentation and it is felt that the stakeholders will be able to make more informed decisions if they attend the meeting and see the presentation.

NDOR's point system assigns voting points based on the ownership of the property, whether the owner is the occupant, and whether the property is in the first-row adjacent to the roadway. Figure 27 is a very helpful graphic contained in the policy document.

Essentially, for each benefited residence or dwelling unit, the property owner will receive 1 point and the residents of that dwelling unit (whether the owner or renter) will receive 1 point. If the residence or dwelling unit is in the front row, the property owner will receive an additional point and will receive a fourth point if the property owner lives in the dwelling unit.

Thus, a single-family dwelling unit not located on the front row, whether owner-occupied or resident-occupied, will receive 2 points on its ballot: one for the owner and one for the resident.

If that single-family dwelling was on the front row, it would receive 3 points if the owner did not live in the unit (a rental unit) or 4 points if the unit was owner-occupied.

For multi-family dwellings, all of the dwelling units would receive 2 points each (one for the owner and one for the resident, whether that be the owner or a renter). If the multi-family facility was on the front row, the owner would receive 2 points for each unit plus an additional point if he or she lived in the unit and the renter would receive 1 point.

NDOR wanted to be sure that property owners had a large say in the abatement decision due to the transient nature of the occupants living in multi-unit complexes in Nebraska. NDOR patterned its voting method after that of North Carolina DOT adding its own features.

People have generally not questioned their assignment of points, appearing to understand conceptually that an owner might receive more points than a renter and that a front-row dwelling unit might receive more points than a unit farther from the road.

NDOR's viewpoints criterion involves a vote by the benefited property owners and residents in which a 75% favorable vote is required for the barrier to be reasonable. This percentage is one of the highest of all of the SHAs and is what was used by NDOR in the past prior to the policy change. This percentage has not been an issue on any of the local projects due to the strong support in favor of noise abatement by the owners and residents. NDOR has no minimum response rate that is required and observed that the four noted local projects all had a good response rate.

In most situations, the neighborhoods consist of owner-occupied single-family residences with a small number of renters. There was one complication on a project where a 4-unit townhome building had an owner association, but where the designation of the actual property owners was not clear. After discussions with the residents, it was decided that each townhome unit would be considered an owner-occupied residence with each unit getting 4 points on its ballot (owner + resident + owner-occupant + front-row owner).

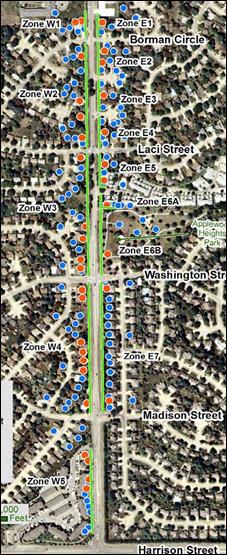

On one local project, a strong positive vote by the stakeholders was felt to be an important factor in justifying the cost of abatement to city leaders. The project was the widening an arterial - 156th Street - from two lanes to four lanes in the City of Omaha, with seven barriers being evaluated. The City has a "green spaces" ordinance that requires a certain setback from the local roads for trees and a sidewalk. Figure 28 and Figure 29 shows a typical cross-section with the barrier on the right and Figure 29 shows a layout for one of the barriers (green receptors will receive 5 dB or greater noise reduction while purple will receive 7 dB or greater reduction).

The barriers were approved on the basis of all of the feasibility and reasonableness criteria, including viewpoints, being met.

Figure 30 (right). 108th Street study area, Omaha, NE (courtesy of NDOR).

Figure 31 (below). Three-story apartments in Zone W5 of 108th Street project (image from www.bing.com/maps/).

On another Omaha project - the 108th Street widening - multiple noise barrier "zones" were studied, as shown in Figure 30 shows the zones. Nine barriers were feasible and reasonable and were voted upon. Two barriers, E3 and E4, were rejected by voters and W5, representing a three-story apartment complex (see Figure 31) was supported by the voters. This example is interesting in the fact that the benefited receptors eligible to vote on Barrier W5 consisted of apartment units on both the first and second floors of the buildings, with outdoor use spaces of patios and balconies. The third-floor apartments were not benefited by the barrier because of their elevation above its top.

NDOR is satisfied with the viewpoints reasonableness criterion in their policy. Future considerations will be given to not including the ballot in the initial mail-out to the stakeholders.

The full text of the section of the NDOR policy on the consideration of viewpoints is presented in Appendix A.

Mariano Berrios of FDOT provided the information used to prepare this section, including the project graphic and photograph. He is the Environmental Programs Administrator in FDOT's main office and was actively involved in the development of the FDOT noise policy. Florida DOT is characterized by a main office headquarters where noise policy and procedural issues are handled and eight district offices where the project work is conducted and managed. FDOT has a statewide noise task team that consists of the main office noise specialist, the noise specialists in each district, and ten consultants who do a great deal of the technical noise work for FDOT projects. The team meets twice a year to discuss policy and technical noise study issues.

Conceptually, the FDOT DOT noise policy's consideration of viewpoints is essentially a continuation of what was in its past policy, where a majority of the receptors affected by a proposed project vote in favor of a barrier for it to move forward in the process.

The biggest change in how the viewpoints of the benefited receptors are considered is the inclusion of property renters in the new policy. Traditionally, FDOT had given the decision to the owners of the properties. With the changes instituted in 23 CFR 772, FDOT devised a formula for considering the viewpoints of the non-owner occupants of apartments, condominiums and mobile home parks. Specifically:

If the owner or the occupant does not reply after repeated attempts to obtain a vote, the unit only gets counted for the percentage of the vote returned for that unit.

Going forward, one of the items that FDOT is considering to change is this 90%/10% split in the vote. Some districts have expressed a desire for more weight to be given to the resident.

FDOT has applied the voting process numerous times since the new policy went into effect. It has not had any major complaints about the process from the affected communities. Concern has been expressed by some of FDOT's consultants that the current process of contacting people is requiring too much time, effort and cost. In one case, the attempts to contact the public involved 12 iterations. While the policy does not have a required response rate of the eligible respondents that it needs for a decision, FDOT endeavors to get as many responses as it can.

Part of the reason for the excessive time and effort is that FDOT mainly uses mailed surveys for gathering votes. Some districts have used multiple mailings when not enough responses have been received. Others have gone so far as to knock on doors of benefited receptors or make phone calls to the benefited owners and residents. Occasionally FDOT districts will use public meetings but they have found that it is harder to get enough people to attend these meetings than it is to get a mailed questionnaire and ballot returned.

On most of its projects, the outcome of the voting has been in favor of the barriers. There have been some conflicts, however, with differing viewpoints of the benefited receptors, the rest of the community, the neighborhood homeowners' association (HOA) or local government leaders.

One example was from a widening project for US 1 in the community of Grove Isle in Vero Beach in southeast Florida. Figure 32 from FDOT District 4, shows the site with the proposed barrier location as the blue line close to the road. The benefited receptors voted in favor of the barrier. However, the rest of the community was largely against the barrier because its installation would cause some special common grounds landscaping put in by the neighborhood to be lost. External to FDOT's involvement, the benefited receptors eventually changed their minds (and their votes) to be no longer in favor of the barrier.

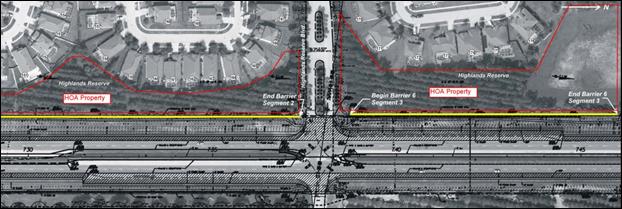

On another project (the widening of US 27 from Barry to Lake County Line, Polk County), the benefited receptors in community of Highlands Reserve in Davenport voted in favor of the noise barrier but the neighborhood HOA was opposed to its construction. Figure 33 shows a portion of the study area with the proposed barrier location indicated by the yellow line and the HOA common grounds outlined in red.

In this case, FHWA and FDOT stood by the requirement in 23 CFR 772 and the FDOT noise policy to consider only the viewpoints of the benefited receptors in making the decision. Figure 34 shows two sections of the nearly completed barrier at the entrance to Highlands Reserve (the sections still need to be painted).

FDOT had a similar situation a number of years back where the City of West Palm Beach did not want a barrier near the entrance to the city because City leaders felt that it would detract from the appearance of the gateway to the City. In that case, FDOT again based its decision on the desires of the affected residents and not those of the City.

On another project, the benefited receptors voted in favor of the noise barrier but did not want it to be as tall as designed by FDOT for visual reasons. FDOT was able to design a lower-height wall that would still meet its other feasibility and reasonableness criteria on noise reduction and cost effectiveness. The change in height was approved by a majority of the benefited receptors and was implemented.

FDOT would not honor a request to lower the height of a proposed barrier if that lowering would cause the barrier to be not reasonable based on its noise reduction and cost effectiveness criteria. However, FDOT has implemented a "perimeter wall" concept in instances where noise barriers would not be feasible and reasonable and yet the department wanted to provide some noise relief to the adjacent homeowners. Under this concept, FDOT has a procedure for qualifying an area based on its distance from the highway and an allowable cost criterion, with a maximum wall height of 10 feet being allowed. The perimeter wall would not be considered to be a "noise barrier."

One question on the application of the FDOT reasonableness criteria in its policy arose in the case of a mobile home park that added spaces for more mobile homes but had not rented out those spaces. As called for in 23 CFR 772 and the FDOT noise policy, a building permit is required by FDOT prior to the date of public knowledge of the highway project for a property to be considered "permitted for development." If so permitted, then the property should be studied for impact and abatement as if it were developed and should be counted in the reasonableness criteria, including the voting on viewpoints. In this particular case, "building permits" are not issued for mobile home placement in a mobile home park. Upon further investigation, FDOT found that different counties use different types of permits for mobile home location, such as a water use or "hook-up" permit. In the county in question, there are two kinds of permits that are considered equivalent to mobile home building permits: a "New Mobile Home" permit (NMH) or (2) a "Flood Mobile Home" (FMH) permit (where a new mobile home permit within a flood plain that has to meet a minimum floor elevation above the ground). Those permits were then used to determine if the new mobile home spaces should be included in the analysis and voting.

One of the difficulties reported by FDOT in soliciting the viewpoints of the affected property owners and residents is in trying to explain to people why only those undeveloped lots with a building permit issued prior to the date of public knowledge of the project are included in the application of the reasonableness criteria during evaluation of abatement. As an example, on a project in southwest Florida, a developer had an approved subdivision plat. Only a few lots had permits even though plans were moving forward for the development of the rest of the lots. However, not enough permits had been issued for the subdivision to pass the reasonableness criteria tests. The problem was ultimately resolved at a high level in FDOT when a decision was made to not use federal funding on the project, which allowed noise abatement to be added without having to meet the requirements in 23 CFR 772 regarding permitting for development.

In summary, FDOT is generally satisfied with its process for the consideration of viewpoints. Concerns have been raised about the amount of time taken or needed to return to the benefited receptors multiple times in order to obtain a vote. Going forward, FDOT may consider requiring a certain response rate of all eligible respondents for a decision on the abatement measure to be considered valid - and then what to do in terms of continued outreach if that minimum percentage is not achieved. The 90%/10% split of the vote between dwelling unit owners and renter may also be reconsidered.

The full text of the section of the FDOT policy on the consideration of viewpoints is presented in Appendix A.

Danielle Shellenberger (Environmental Planner in charge of noise and air quality, PennDOT Bureau of Project Delivery) and Rob Kolmansberger (consultant to PennDOT at Navarro & Wright Consulting Engineers, Inc.) provided the information used to prepare this section, including the sample ballot and project graphics. PennDOT has had good success in the implementation of the consideration of viewpoints criterion in its noise policy. Its policy requires 50% or more of the received votes to be in favor of the abatement measure for it to be reasonable, with no minimum required response rate for a vote to be considered valid. Owner-occupants of a property get one vote, and in the case of rental units, the owner and renter each get one vote.

PennDOT is decentralized with a number of "Engineering Districts," where most of the project-related noise study work is done by district specialists and consultants. Most of the need for noise abatement has fallen within only three or four of the districts that include Pennsylvania's major urban centers. It is roughly estimated that the voting process has been used on 20 to 30 projects a year. In almost all of the cases, the vote of the benefited receptors has been in strongly in favor of the abatement measure and, in most cases, a large majority of the eligible voters are participating in the voting process, even though PennDOT does not have a minimum response rate.

PennDOT has purposely built flexibility into its policy to give each district the maximum opportunity to deal with the circumstances in each situation, which are sometimes unique to a particular project. The desire for flexibility is especially important in terms of the public involvement process. The policy states, "As long as it is documented in the Final Design Highway Traffic Noise Report how benefited receptor unit owners/voted... the method of obtaining votes... shall be determined by the Engineering District on a project-by-project basis."

Within the framework of that flexibility, there has been some movement to a more standardized process including a presentation of proposed barrier details at a stakeholders meeting and use of a basic template of a voting form, as illustrated in Figure 35. The meetings with the stakeholders can range from formal presentations in an auditorium to "gathering around a kitchen table" when a small number of benefited receptors is involved.

Typically, a certified mailing is made to the benefited receptors. This mailing does not include a ballot because the intent is to try to get as many people as possible to come to the meeting to learn about the proposed abatement measure. When meeting turnouts are low, the districts have the flexibility to follow up as often as possible in a good-faith effort to gain a true sense of the desires of the benefited receptors. That follow-up could include additional mailings and door-to-door visits.

Ballots distributed at the meeting would typically also contain an opportunity to vote or express preference on the type and color of the barrier surface. There is some support to reduce the number of aesthetic options offered to the benefited owners and residents, in an effort toward more standardization, and there is also support for giving each district as much flexibility as possible to suit the community in the best manner. In some cases, the voting on the aesthetics of a barrier is summarized on a map of the area to get a better sense of who wants which choice in which location.

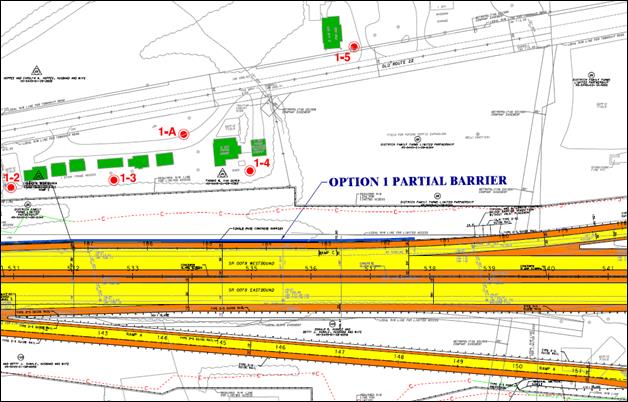

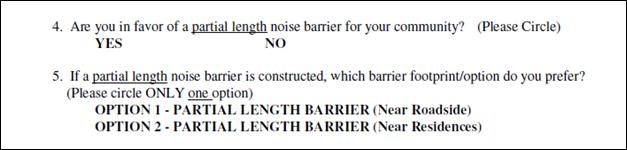

The PennDOT policy is one of only two SHA policies that addresses the concept of partial traffic noise abatement. The policy states, "When assessing those votes that are not in favor of the proposed noise wall, the Engineering District needs to assess the number and location of these opposing votes on a noise barrier by noise barrier basis. This may result in partial highway traffic noise abatement or the inability of satisfying the request of the opposing votes."

An example was cited of a recent situation on Interstate 78 (section 13M), illustrated in Figure 36. A resident at one end of the proposed barrier was not in favor of the barrier. PennDOT was able to reanalyze the barrier and reduce its length by 200 feet so it would not fully block this receptor while not compromising the performance of the barrier for the other impacted receptors. PennDOT is more willing to consider partial noise abatement in the case of these "end" receptors rather than ones in the middle of a neighborhood because any gap in the middle of a barrier would seriously degrade its performance for nearby receptors. In any case, the reduced-size barrier would still need to meet the feasibility and other reasonableness criteria in the PennDOT policy (including achieving a noise reduction of 7 dB at one benefited receptor and meeting the allowable cost per benefited receptor criterion).

In another section on the same project, PennDOT was able to design two separate options for the barrier: one at the edge of the shoulder of the road and one near the ROW line that would provide a bit more noise reduction but would be more visible to the residents. In the solicitation of viewpoints, PennDOT found the benefited receptors to be in favor of the edge-of-shoulder option because they did not want to have to look at the wall. Figure 37 shows an excerpt from that voting form.

A third situation on this project highlighted the assignment of votes to owner-occupants and renters. The policy states, "The owner of each benefited receptor unit shall receive one vote of equal value for each benefited receptor owned. The renter shall receive one vote for the unit in which they reside." Thus, an owner-occupied residence would receive one vote while a rental residence would receive twice as many votes (one for the owner and one for the renter). In this particular example, the noise analysis area consisted of a single property with eight long-term rental cottages owned by a single owner (in concept, akin to detached apartments). The owner received one vote for each cottage for a total of eight possible votes. Each renter received one vote, for a total of eight possible votes, meaning, overall, there were 16 possible votes. The owner and three of the renters voted. Thus, there was a total of 11 votes cast. Achieving a percentage of 50% or more required six votes in favor. With the owner voting affirmatively, his eight votes provided the needed margin.

The question arose as to what could have happened in a situation where the owner was the occupant of one of the cottages. Then there would be a total of only 15 votes: one for the owner-occupied cottage, seven for the nonresident owner and seven for the renters. It is unlikely that this change would affect the outcome of the vote. However, a case could arise where a larger number of positive votes by owner-occupants of a group of residences could be outweighed by negative votes from a smaller number of rental properties where the non-occupant owner(s) and their tenants vote against the barrier. Consider 16 properties with 10 owner-occupied units (10 votes) and six rentals (12 votes): the six rental units could carry the vote over the larger number of owner-occupied properties.

PennDOT may consider a change to this section of its policy so that each dwelling unit receives the same number of votes, whether owner-occupied or renter-occupied, splitting the vote between tenant and nonresident owner for rental properties.

In summary, the process by which PennDOT considers the viewpoints of the benefited property owners and the residents has gone well. Flexibility in the process, especially as it relates to public involvement, has been felt to be critical to meet the often unique needs of communities adjacent to highway projects.

The full text of the section of the PennDOT policy on the consideration of viewpoints is presented in Appendix A.

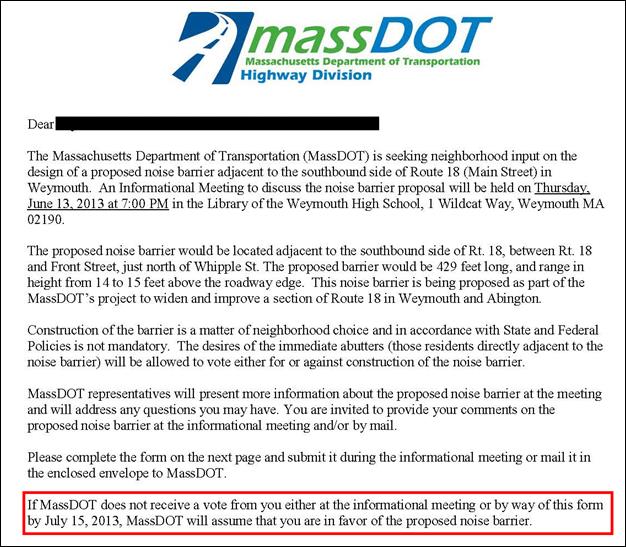

James Cerbone provided the information, sample letters and ballot used in this section of the report. He is Project Manager in charge of noise in the Environmental Services Section of MassDOT's Highway Division. The MassDOT noise policy requires a two-thirds (67%) positive vote of the weighted total number of residential votes. (The weighting system will be discussed below.) It is important to note that a non-response in the voting is considered a "yes" vote in determining if the 67% requirement has been achieved. There is no minimum response rate in the number of votes received in terms of a percentage of those eligible to vote. The policy is also only one of a few where special mention is made of owners of undeveloped land that has been permitted for development.

The voting process has been used numerous times since 2012 when the new policy went into effect. Approximately 20 barriers, mostly for widenings or interchange modifications, have been approved under the new policy.

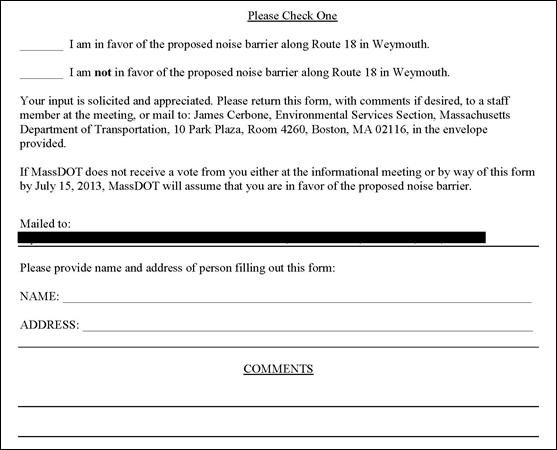

The process involves sending out a letter by certified mail to the benefited property owners and residents. The letter provides notice of a neighborhood meeting and details on the barrier's location, height and length, more recently in the form a fact sheet. The letter also includes a ballot that identifies the recipient by name (if the owner) or as "Resident" (if a renter), along with the address. The ballot asks the recipient to vote in favor or opposed to the barrier and gives the opportunity to provide comments and to express preference on a color or texture for the barrier.

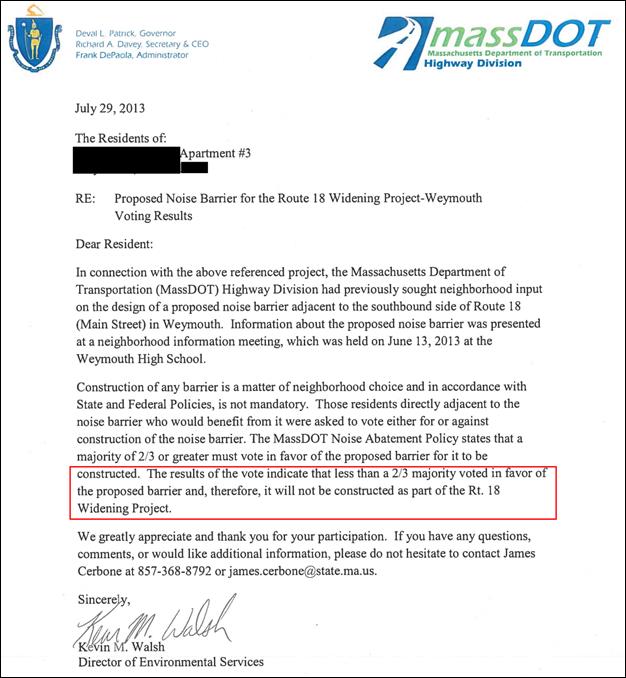

At the meeting, the proposed barrier is presented, an opportunity is provided for local input into the development of the barrier project, and ballots are collected. After the meeting has been held, MassDOT counts the votes and determines if the two-thirds majority is in favor of the barrier. MassDOT then sends a letter to all of the benefited receptors with the results of the voting along with its decision to move forward or not with the barrier.

MassDOT will accept the votes ahead of the meeting or at the meeting and will accept them by e-mail as well as in person. However, it is clearly stated that this ballot is the only opportunity that the benefited receptors will have to vote.

A sample letter for the informational meeting and ballot (not including an aesthetics preference vote) are shown below as Figure 38 and Figure 39. Figure 40 shows a sample results letter indicating that the barrier did not receive 67% of the vote in favor of it.

The current process has evolved from what is stated in the policy. The policy notes that after the public information meeting, a survey of the property owners and residents of the benefited receptors is conducted by mail. The policy notes that a "second public meeting is held after the noise barrier design progresses further to present more specific project information to the affected area." Currently, as noted above, only one meeting is held, where people both vote on the barrier and the color and texture.

The MassDOT policy specifies the number of votes based on whether or not the dwelling unit is owner-occupied or rented, whether it is first-row or other row, and if it is other than existing residential (Activity Category C or D or undeveloped land permitted for residential development. Figure 41 shows Table 5 from the policy on the vote allocation.

As shown, a first row residence will receive five votes and a renter will receive one vote. If the property is owner-occupied the owner would have all five votes. For the rental property, the owner would have four votes and the renter would have one vote. Similarly for rows beyond the first row, the property would get three votes, which would be divided as two for the owner and one for the renter if it is a rental property. No situations involving voting on Activity Category C or D or permitted undeveloped lands have yet to arise.

Two instances of barriers being voted down by the benefited property owners and residents were cited. The first case was along Interstate 93 Southbound at Columbia Road in Boston where the benefited voters were opposed to the view across the road being obstructed. Figure 42 shows the general project area.

The second project was Route 18 in Weymouth-Abbington, MA. A FONSI was issued in 2009, prior to the adoption of the changes in 23 CFR 772 and the new MassDOT noise policy. The noise analysis in the EA documented that most first row receptors along Route 18 would be impacted and that second row receptors for the most part would not be impacted. The analysis then evaluated the feasibility of noise abatement to obtain the required noise reduction. The result of the analysis was that noise barriers would not be feasible for most front-row receptors because of the need for gaps providing safe sight distances for driveways and side streets.

One noise barrier, however, was determined to be feasible and reasonable in terms of noise reduction design goal and MassDOT's cost effectiveness index. Figure 43 shows the area where the barrier would be located, between Route 18 (Main Street) and Front Street This barrier would benefit nine residences. Four of the residences were apartments in one building that were all owned by the same person. There were five other owner-occupied residences.

During the public involvement process to determine the neighbors' viewpoints about the barrier, the apartment owner along with one other property owner did not want the barrier because of the visual impact. With the apartment owner allocated four votes per apartment unit, the vote failed to achieve the needed two-thirds majority even though four of the other property owners were in favor of the barrier. Therefore, this barrier was no longer included in the project.

MassDOT will be re-evaluating its noise policy in 2016, but at the moment it does not foresee any changes of the viewpoints criterion or the voting process. The opinion was expressed that this portion of the policy seems to be working well.

The full text of the section of the MassDOT policy on the consideration of viewpoints is presented in Appendix A.

Mr. Jin Lee of Caltrans District 7 in Los Angeles and Mr. Jim Andrews in the Headquarters' Division of Environmental Analysis provided the information discussed in this section. Mr. Lee is Branch Chief/Noise & Vibration Branch, Office of Environmental Engineering, Division of Environmental Planning. Mr. Andrews is a Senior Transportation Engineer. Caltrans, like Pennsylvania DOT, consists of a main office headquarters and many districts (12) around the state. Districts with urban centers tend to have many more noise barrier projects than the more rural districts.

The Caltrans noise policy states "that if more than 50% of the votes from responding benefited receptors oppose the abatement, the abatement will not be considered reasonable." Caltrans' goal is to provide noise abatement/benefits to the impacted areas. Caltrans' default position is that noise barriers that are determined to be reasonable and feasible are a benefit to the community to reduce traffic noise. Noise abatement should be provided to impacted areas unless there are clearly stated and active opposition to the recommended abatement measures by a majority of the benefitted receptors. The assumption is that a non-response equates to implied concurrence for and lack of opposition to the abatement measure.

When Caltrans drafted its policy, it was trying to address the concerns of both the tenants in high-density, multi-unit complexes and the property owners. The philosophy was that while tenants frequently change, the property owner has a long-term interest. The intent was that for a given property, the owner had a controlling interest but the tenants should get some voting power. In most cases, barriers that are both feasible and reasonable have benefitted residences from many properties and therefore the tenants of one property may be the swing vote for building the wall even when their owner opposed it. This issue was difficult to resolve to everyone's satisfaction.

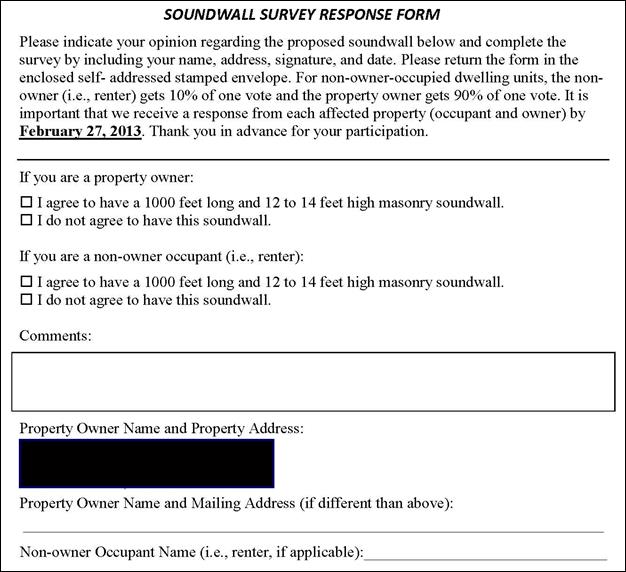

The policy states: "For non-owner-occupied dwelling units, the renter gets 10% of one vote and the owner gets 90% of one vote." Currently, District 7 interprets this split as: the owner of the apartment building would get 90% of one vote and each renter would get 10% of one vote. Thus, if there were one owner and 20 renters, the owner would get 0.9 votes and the renters would get a total of 20 x 0.1 votes or 2 votes. This interpretation means that the owner would not automatically control the vote: 10 renters could out-vote the owner.

An alternative interpretation would be that a 20-unit apartment building would have a total of 20 votes, one for each unit. The owner would get 90% of 20 votes for a total of 18 votes where each renter would get 10% of 1 vote for a total of 2 votes. In this arrangement, the owner's vote would always control the result. (In the case of a single-family residence as a rental, the owner would get 90% of one vote or 0.9 votes and the tenant would get 10% of one vote or 0.1 votes. In this case, the owner's vote would also control the result.)

Caltrans' policy is also unique by its inclusion of a discussion of noise abatement located on private property. In such cases, 100% of the owners upon which the abatement would be placed must be in support of the proposed abatement. If no response is received from a property owner, that vote is considered as a vote against abatement. In such cases, Caltrans will make several efforts to contact all of the property owners, even including knocking on doors. It is not uncommon for Caltrans to recommend a noise barrier on a private property. Generally, these situations occur when the houses are up on a hill above a freeway and would have a line-of-sight over any barrier placed on the ROW or near the edge of pavement of the freeway. However, rarely has Caltrans built a barrier on private property. Often, people do have a view that they wish to maintain and even opposition from a single property owner could prevent the barrier from being found reasonable.

The ways in which the consideration of viewpoints is implemented can vary from district to district. In District 7, the general outreach method is first to hold an open house to discuss the proposed barrier project. If there is general consensus in favor of the barrier, Caltrans documents that consensus and conclude the process of soliciting viewpoints.

If opposition to the barrier is expressed at the open house, depending on its degree, District 7 then conducts a survey by certified mail of the benefited receptors (note that while the policy says registered mail, the district has found certified mail to work well). Caltrans will send out an initial letter ballot and allow three to four weeks for a response. Caltrans will then send out a second letter to the non-respondents and, if needed after another response period, a third and final letter. That third letter would indicate that it would be that recipient's last opportunity to vote on the barrier. If no response is received, District 7 considers the non-respondent as voting in favor of the barrier. The language in the policy states: "if more than 50% of the votes from responding benefited receptors oppose the abatement the abatement will not be considered reasonable."

Generally, in most of its applications of this voting process, District 7 has found the benefited property owners and residents to be in favor of the barrier at the open house. As a result, there are not many cases when a survey was needed.

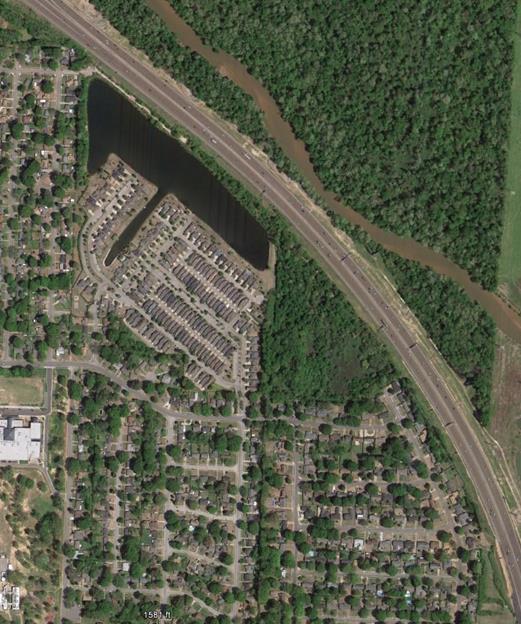

One case was described where the residents did vote against the barrier. The project was the terminus of State Route 2 south of its interchange with Interstate 5 in Los Angeles, CA. A series of noise barriers was recommended along this project and most of the barriers were voted upon favorably by the benefited owners and residents. However, in one section near the end of the project, the noise barrier would have to be added atop an existing retaining wall along Allesandro Street to provide noise reduction to the residences elevated above the roadway. Figure 44 and Figure 45 show views of this neighborhood area.

Figure 46 shows an excerpt of the ballot sent to the owners and residents under a cover letter that described the project and the proposed barrier. The residents did not want their view blocked by a barrier and voted against the barrier. Figure 47 is an excerpt from the letter sent to the owners and residents informing them of the results of the vote and the Caltrans' decision to not move forward with the proposed barrier.

In summary, the Caltrans policy on viewpoints is flexible in how it is interpreted by each of its districts. District 7 has implemented a flexible process where formal voting is not necessary unless opposition to the barrier is raised. The policy features a splitting of owner and renter votes on a 90%/10% basis. The policy is also unique in its specification of a 100% positive vote for any abatement feature located on private property.

The full text of the section of the Caltrans' policy on the consideration of viewpoints is presented in Appendix A.

Darlene Reiter, Ph.D., P.E., of Bowlby & Associates, Inc., provided this information on behalf of TDOT. Dr. Reiter has a part-time consultant assistance staff position at TDOT for assisting in managing TDOT's noise and air quality programs. She is also a researcher on this task order.

TDOT's noise policy states that TDOT "will conclude that a community desires the construction of a noise barrier unless a majority (at least 51%) of the benefited property owners and residents indicate that they do not want the proposed noise barrier." [italics added] TDOT only considers the votes that are received. One consequence is that a minority of benefited receptors could vote down a barrier if they happen to be in the majority of the received votes when there is a low response rate.

TDOT counts responses from residents or owners of properties that are predicted to be impacted as well as benefited as two votes. Votes for properties that are benefited but not impacted are counted as one vote. If an impacted and benefited residence in occupied by the owner, the owner casts both votes. If the residence is rented, the two votes are split with one for the owner and one for the renter. For properties that are benefited but not impacted, the one vote is split with 0.5 votes for the owner and 0.5 votes for the renter. In either case, if one stakeholder does not vote, that unused portion of the vote is not counted.

TDOT's noise policy also states that "The input of the benefited property owners and residents will generally be received at planning, NEPA or design public hearings or public meetings. Input received at these hearings or meetings may be supplemented, as necessary, with formal survey methods on a case-by-case basis as discussed in the TEPM." TDOT developed a standard noise barrier questionnaire, which it feels has worked well. TDOT Noise Procedures provide additional guidance on the solicitation of viewpoints stating: "If significant opposition exists and there is not clear support for the construction of the proposed noise barrier(s), TDOT will conduct a certified mail survey to solicit the views of the benefited residents and/or property owners…"

The process has been applied to four projects where barriers were determined to meet the first two reasonableness criteria for noise reduction design goal and cost-effectiveness. Only one of these cases involved significant opposition to the proposed barrier. In this case, the formal survey process outlined in TDOT's Noise Procedures was followed including a certified mailing and a follow-up letter to non-respondents.

TDOT has solicited the viewpoints for the other three other projects at planning, NEPA or design public hearings or public meetings. Surveys were also subsequently mailed to benefited residents and property owners on two of these projects. On one project, the public meeting conflicted with a religious holiday which affected meeting attendance. On the other project, the homeowner's association requested that TDOT send surveys to all of the residents.

The results are summarized in Table 36, with the first column also listing the figure that shows the project area. At TDOT's request, these projects are listed anonymously and referred to as projects TDOT-1 through TDOT-4. These projects provide an excellent mix of community types and ownership: primarily owner-occupied single family homes; single family homes and condos; mobile homes; and rental apartments. The table includes the number of impacted and benefited dwelling units. It also includes the number of responses (and their characteristics), and the voting results and reasonableness decision.

TDOT has no current plans for revisions to the consideration of viewpoints portion of its policy. However, there is some concern that the application of the 50%/50% split for both owners and residents of rental communities (apartments and mobile home communities) results in the owner making the decision since they would get one vote for every unit. If a single unit is vacant or a resident does not respond, the owner automatically controls the majority of votes.

A different weighting system for communities where all units are rented (i.e., apartments or mobile home communities) might be considered to ensure that the owner doesn't have complete control of the outcome. An example might be where the property owner of the apartment complex or mobile home park has 40% of the vote for each rental unit and the residents have 60%.

The issue of how to assign votes to commonly used areas of rental communities could also pose a challenge. Units may not have dedicated balconies or patios but instead share common areas (lawns, playgrounds, patios, etc.) with all other units. This situation occurred on Project TDOT-3. However, there was unanimous support (owner and residents) for the barrier, thus it was not an issue.

While TDOT has not encountered this issue, there is also a concern that an apartment owner could dictate the decision for barriers for mixed-use communities that included single-family homes and apartments (as described in the example earlier in this chapter).

TDOT's previous policy did not state specifically how the viewpoints would be considered. It simply said that: "The views and desires of the impacted residents will be considered by TDOT in its final decision. The input of the impacted residents will be received at design public hearings or public noise meetings." The changes made for the new policy, while raising some concerns, have been viewed as a success. By formalizing and standardizing the process, TDOT is achieving community consensus with defendable decisions.

The focus of this research was on Activity Category B (residential) land uses. However, one-third of the SHA policies contain language on the other Activity Categories in 23 CFR 772. That text is presented below for informational purposes without any analysis.

Colorado: "The noise barrier preference survey is normally based on residential areas; however, mitigation for commercial and special-use areas would be based on a survey of the business operators and property management/owners and/or the officials with jurisdiction."

Florida weights "offices and businesses (100% owner occupied/80% owner non-occupied)/ 20% renter).

Illinois: "The noise abatement evaluation for impacted Activity Category D land use facilities based on the interior NAC should first be evaluated using noise barriers. Noise insulation will only be considered for Activity Category D if noise barriers are determined to be not feasible or not reasonable and there is a noise impact based on an interior evaluation. If the only reason the noise barrier is not considered reasonable is due to the outcome of the solicitation of benefited receptor viewpoints, the consideration of noise insulation should be discussed with the IDOT Noise Specialist and FHWA.

"As an example, if a noise barrier is determined to be feasible, and achieves the reasonableness criteria of the noise reduction design goal and the cost-effective evaluation, the desire of the benefited receptors will be solicited. If the overall viewpoint indicates a desire for the noise barrier, the noise barrier will be recommended for implementation. However, if the receptor viewpoints indicate an overall lack of desire for the noise barrier, sound insulation will only be considered as a possible noise abatement measure on a case-by-case basis. Noise insulation measures should be discussed with IDOT and FHWA during project development or at coordination meetings."

Kentucky: "Properties with special use such as churches, schools, playgrounds etc. shall be weighted in a manner similar to that described under the Cost Effectiveness paragraphs of this section. The voting member shall be identified as the leader or head of the organization such as the school superintendent, park superintendent, etc. For each such property, both a resident and owner ballot shall be solicited, weighted to account for equivalent residences and, if appropriate, further weighted in accordance with the respect to paragraph 5 of this section."

Maryland: "If a property, such as a commercial or industrial site, does not have a noise sensitive use, then that property is excluded from the voting."

"Special land use areas (Category C) with identified benefiting noise sensitive use areas are counted based upon the number of equivalent residences (ER) based on an assessment of the linear frontage of the subject activity area divided by 125. The weighting of votes cast involving Category C activities shall follow the same protocols as established and described in the previous section for property owner residents, property owner non-residents, and renter residents."