Table of Contents

List of Figures

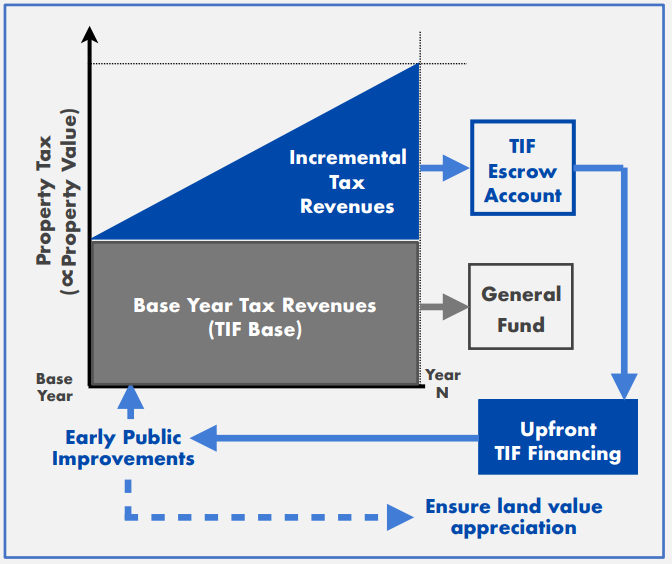

Figure 1. Diagram displaying the finance structure for tax increment financing.

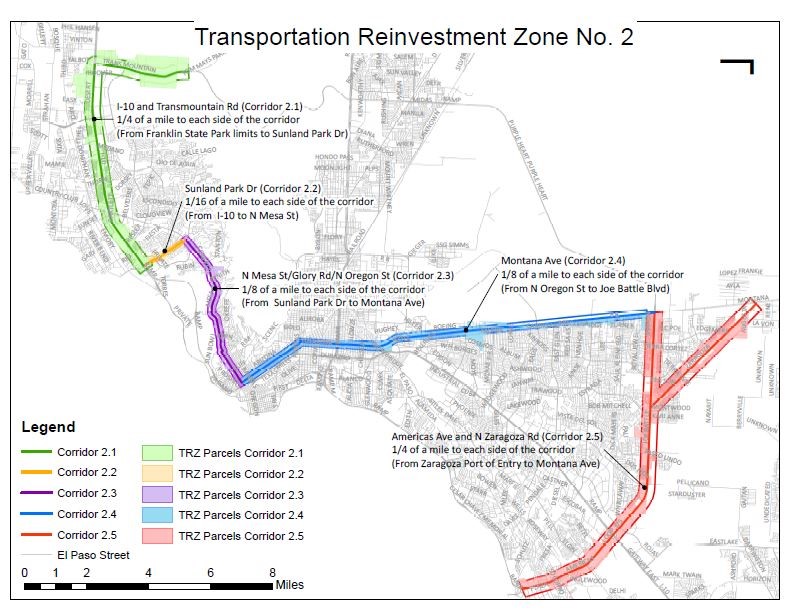

Figure 2. Transportation Reinvestment Zone corridors along the I-10 interchange.

This report highlights noteworthy practices and key recommendations identified in the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Every Day Counts Round 5 (EDC-5) peer exchange focused on value capture, held on September 17-18, 2019, in Chicago, Illinois.

The FHWA EDC program identifies and deploys proven, yet underutilized innovations to shorten the project delivery process, enhance roadway safety, reduce traffic congestion, and integrate automation. Proven innovations promoted through EDC facilitate greater efficiency at the State and local levels, saving time, money, and resources.

FHWA works with State departments of transportation, local governments, tribes, private industry, and other stakeholders to identify a new collection of EDC innovations to champion every two years. EDC facilitates regional summits for transportation leaders to discuss and identify opportunities to implement the innovations that best fit their needs. Following the summits, States finalize their selection of innovations, establish performance goals for the level of implementation and adoption over the upcoming two-year cycle, and begin to implement the innovations with the support and assistance of FHWA technical teams.

Value capture was identified as one of the 10 EDC-5 innovation techniques for the 2019-2020 cycle.

The Illinois peer exchange was the first in a series of EDC-5 peer exchanges aimed at facilitating knowledge transfer and capacity building by connecting peers from different States and regional and local agencies to discuss best practices about value capture. The Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) requested the peer exchange to learn about methods of implementing value capture techniques in Illinois, specifically focused on innovative project financing and delivery. The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) hosted the peer exchange.

Julie Kim, Senior Fellow at Stanford's Global Projects Center and Fellow at the New Cities Foundation, served as a subject matter expert on value capture, researching best practices and assisting FHWA in preparing materials and selecting peers for the peer exchange.

Prior to the exchange, representatives from FHWA's Center for Innovative Finance Support, FHWA's Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty (HEP), and the Volpe Center worked with IDOT to identify peers that would be able to share their experiences, lessons learned, and recommendations for using value capture techniques to finance transportation infrastructure projects. The peers selected for the exchange were:

The two-day peer exchange was held on September 17-18, 2019, at CMAP's headquarters in Chicago, IL. Participants included the four peer presenters, facilitators from the Volpe Center, Dr. Kim, and representatives from the following organizations (in alphabetical order): CMAP, FHWA headquarters, FHWA Illinois Division Office, IDOT, Illinois Tollway, Kane County Department of Transportation, Metra, Metropolitan Planning Council, and Regional Transportation Authority (RTA). Approximately 20 people from various groups and agencies attended the two-day event. A full list of attendees is available in Appendix B of this report.

The exchange began with a brief round of introductions and remarks from IDOT and CMAP on their goals for the exchange. The four sessions on the first day included an introduction to value capture techniques, followed by sessions focused on tax increment financing and transportation reinvestment zones, special taxes and fees, and developer contributions. These sessions featured a brief overview by the subject matter expert and one to two peers, followed by discussion with other peers and participants. On day two, the sessions focused on joint development and other tools based on development rights and entitlements, as well as an open discussion of key takeaways and next steps. An agenda for the program is included in Appendix C of this report.

Value capture refers to a set of techniques that take advantage of increasing property values, economic activity, and growth linked to infrastructure investments to help fund current or future improvements. Value capture is rooted in the notion that public action should generate public benefit.

FHWA staff and Dr. Kim provided materials describing in depth the techniques of value capture and the benefits realized through their implementation. The materials are provided in full in Appendix D of this document.

Over the course of the two-day exchange, peers shared their experiences and engaged in discussion about value capture projects and techniques. Example techniques and projects are shared below.

Value capture techniques, like tax increment financing (TIF), help capture property value increases within designated districts that are attributable to transportation investments. Without increasing the tax rate, a TIF enables earmarking of incremental tax revenues to be put into separate escrow accounts, which can then be leveraged to secure upfront TIF bond financing to pay for public improvements. These public improvements further support value appreciation. The longevity of TIF districts varies from State to State, but, in general, earmarks for TIF-related financing end when the investments in public improvements for TIF districts have been paid off. See Figure 1.

To note, although agencies can issue bonds backed by activated incremental tax revenues upfront, the tax revenues are not always guaranteed. For this reason, some States restrict the issuing of TIF bonds until the incremental revenues reach a minimum threshold level. In California, for example, the value increase must be at least 25 percent above the base level before bonds can be issued.

Source: Dr. Julie Kim (2019)

Figure 1. Diagram displaying the finance structure for tax increment financingElizabeth Schuh, Principal Policy Analyst at CMAP, described CMAP's desire for value capture to play an increasing role in transportation project financing in the Chicago region. CMAP noted that it can be challenging to convince local jurisdictions to use value capture techniques. The agency has created resources on value capture to educate its stakeholders on the subject; CMAP includes value capture strategies and recommendations in their regional long-range transportation plans, and has released two reports on value capture analysis in the CMAP region.1

Chicago currently uses TIF districts and Transit Facility Improvement Areas (TFIAs) in some transportation projects. CMAP's project analysis found that, although TIF and TIF-like districts provide the highest revenue potential in Chicago compared to other methods, underinvested areas need significant additional resources to supplement value capture revenues. This is especially true given that TIFs can be used in Chicago only if specific blight, age, and property value criteria are met as stipulated in law. CMAP, IDOT, and other partners have used TIF districts and TFIAs to construct the Central Lake Thruway/Route 120 Bypass and the 425-space parking garage near the Wilmette Metra Station. The Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) is currently evaluating the potential to extend the Red Line south from its existing terminus at 95th Street to 130th Street, and add four new stops along that length. CTA is considering utilizing TIF to fund a new CTA railyard within the project's geographic area.

Many States, including Illinois, allow the use of TIF districts, although they may be called different names and have variations in applicability, such as transportation allocation districts in Georgia, urban renewal areas in Oregon, and transportation reinvestment zones (TRZs) in Texas.

Raymond Telles, Executive Director of the Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority (CRRMA) in Texas, shared his extensive experience with TRZs. CRRMA is a unique authority with geographical operation in the county of El Paso, TX; the State of New Mexico; and the country of Mexico. This jurisdiction stems from the plethora of transportation assets that cross through multiple towns, counties, and–at times–State and international boundaries.

CRRMA used TRZs for the Americas Interchange Project in El Paso, TX. This project included the design and construction of eight direct connectors and other related improvements for the Loop 375 and I-10 interchange. Construction was pursued in phases to allow for gradual generation and spending of funds. The city of El Paso established three TRZs, the revenues of which were assigned to CRRMA in order to issue debt and finance the design and construction of the project’s phases. CRRMA packaged borrowed capital as a Build America Bond (BAB), half of which was used to pay down the debt with the city of El Paso. See Figure 2 .

Source: CRRMA (2019)

Figure 2. Transportation Reinvestment Zone corridors along the I-10 interchange.The Americas Interchange Project offers the following key lessons:

Special assessments–usually special taxes and fees–can fund public improvements and services within a designated district. These improvements are financed by property and business owners and tenants who live within the district. Special assessments involve a new levy imposed on the property and business owners and tenants over a specific time period. Generally, special assessments can be used for both physical improvements (such as construction and maintenance) and public services (including police and fire services).

Special assessment districts are called by different names in different States. Broadly, the formation of special assessment districts can be triggered by local community and business improvement needs. These are commonly referred to as business, community, or local improvement districts (or BID, CID, or LID). More often than not, these improvement districts are limited to a single jurisdiction. Special assessment districts can also be triggered specifically by transportation infrastructure needs. Transportation improvement or transportation development districts (TID or TDD) are typically formed in high-growth areas where infrastructure needs cannot be met through local or State capital programs alone. The use of TID/TDD typically involves multiple jurisdictions and regional/State-level transportation needs.

Special assessment districts have been challenged more recently in courts due to an increased financial burden on property owners, who also are the primary beneficiaries of these improvement projects. In response, some States have introduced new regulations to restrict special assessment districts, such as requiring voter approval by a two-thirds margin. Increasingly, the basis for special assessments is confined only to special benefits that are unique, measurable, and direct, with the burden of proof generally on local governments.

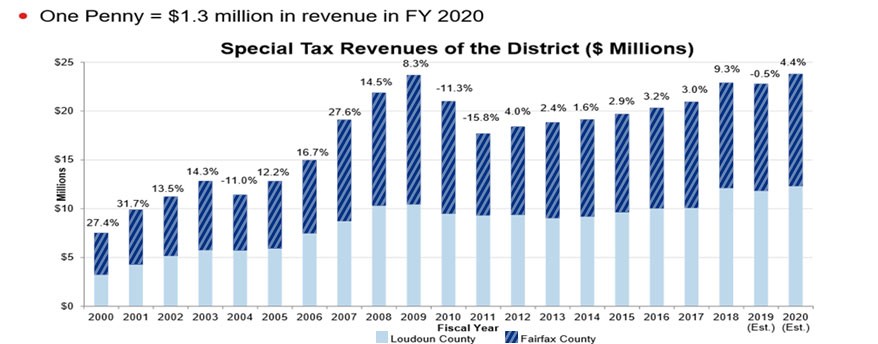

Brent Riddle, Senior Transportation Planner for Fairfax County, VA, shared how Fairfax County used TIDs to finance improvements to the State Route 28 corridor. In 1987, local business owners formed the TID in response to roadway capacity concerns. The TID is governed by a commission comprised of nine members–four elected officials from Loudoun County, four from Fairfax County, and the Secretary of Transportation for the Commonwealth of Virginia–and a landowners' advisory board with no voting power. The TID has financed seven interchanges and five widening projects through issuing bonds that are paid for by revenues generated along the corridor. See Figure 3.

The Route 28 TID offers the following key lessons:

Developer exactions are the financial responsibilities that local governments place upon developers to provide some or all of the public improvements necessitated by their development projects. They are generally imposed as conditions of approval at major project milestones and directly linked to land use entitlements. As most exactions are collected at the project outset, projects funded through this value capture mechanism have flexibility to generate and use funds early when the public improvements are being made.

Developer exactions can be either voluntary or contractual. They primarily result in developers' dedication of land for streets, sidewalks, and utility easements, and involve the transfer of land ownership to local agencies. Developers can also provide voluntary in-kind contributions in the form of public services and/or physical facilities.

Impact Fees and Linkage Fees

Local governments can impose impact fees and other mandatory exactions through the exercise of their police power, which permits restrictions on private activities to protect public health, safety, and welfare. However, impact fees are also commonly contested, and therefore have historically been determined by court rulings. Impact fees are associated with cost of any incremental public service capacity necessitated by new development projects and can include a wide range of improvements and services both on- and off-site, such as utility improvements. Linkage fees are typically associated with new, large-scale developments and used to pay for secondary effects, such as offsetting significant increased traffic or providing affordable housing. In transportation, impact fees can also be called mobility fees, traffic impact fees, intersection development charges, or system development charges.

Scott Hamwey, Director of Transit Planning at the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), described the benefits and challenges of developer contributions, especially for transit projects. He shared details from the following MassDOT projects:

The MassDOT project examples offer the following key lessons:

Gregg Hostetler, Executive Vice President of Structural Assessment and Alternative Contracting for CONSOR Engineers, shared his experiences with developer contributions in Osceola County, FL. Osceola County, primarily rural, sought to use impact fees to finance improvements to existing roads and bridges, amounting to nearly $1 billion over a ten-year period. The ensuring projects were bundled using alternative contracting methods, such as the Construction Manager/General Contractor (CM/GC) process. In the CM/GC process, the project owner hires a contractor to provide feedback during the design phase before the start of construction. This method was highlighted during Round 2 of FHWA's Every Day Counts Initiative (EDC-2). See Figure 4.

The impact fees were assessed on new developments to provide funding to the county. They were set at the issuance of the building permit and needed to be paid prior to construction. The housing crash and recession in 2008 introduced challenges to this process and led to a moratorium from 2008 to 2010. The county was later able to use revenues from impact fees to pay the debt service on bonds used to finance the county's infrastructure projects.

| Program Goals | Projects were bundled in a CM/GC program to speed up delivery and save money. |

|---|---|

| Bridge Selection Criteria | Bridges were part of roadway projects. |

| Delivery and Procurement Method | Construction Manager/General Contractor (CM/GC) – Qualifications-Based Selection. |

| Funding Sources, Financing Strategy | 100% locally funded through impact fees. |

| Environmental, Right-of-Way, and Utility Considerations | CMs were involved in planning and design to minimize impacts to the environment, right-of-way, and utilities. CM was the lead for all utility coordination efforts. Projects were built in "mini" phases. Instead of waiting for the entire project to be completed and clear for permitting, right-of-way, and utilities, segments of the projects were constructed as soon as they were ready, greatly accelerating the projects. |

| Risks | The risk shared between the owner, designer, and construction manager. All entities worked together to ensure the designs were constructible and within budget. Due to the fact that plans were less detailed, overruns were budgeted for instead of relying on errors and omission claims. |

| Owner Management/Quality Assurance | The construction engineering inspection (CEI) firm was hired by the owner. The CM included the CEI in the plan reviews and developed to ensure constructability. The role of the CEO during construction was reduced. The CM manages the general contractors and the CEO ensures quality. |

| Stakeholder Communications | The Osceola County administration completed an intensive training effort to educate the design forms and contracting community about the benefits of CMGC. Once chosen, the CM was responsible for communication with the affected community. |

The Osceola County project example offers the following key lessons:

Joint developments involve monetizing the unused land use entitlements on publicly owned property by transferring them to private developers for some form of revenue and/or cost-sharing arrangements. These developments can involve sale or lease of development rights above, below, or adjacent to transportation rights-of-way, such as above railroad tracks or expressway turnpikes. These tools often can serve as the means to meet larger policy goals, such as promoting transit-oriented development.

Scott Hamwey described the benefits and challenges of joint developments for highway and transit projects. To date, MassDOT has not successfully utilized naming rights as a value capture tool, but is currently exploring a naming rights solicitation for transit assets. The agency has had success with joint development, particularly those related to air rights. Mr. Hamwey shared details from the following MassDOT projects:

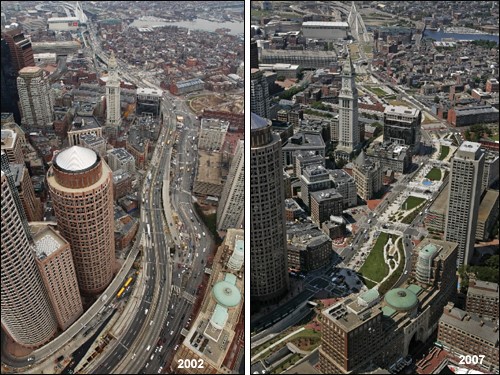

Source: David L. Ryan, Boston Globe (2007)

Figure 5. Before and after financing and construction of the Rose Kennedy Greenway, using air rights.The MassDOT project examples offer the following key lessons:

This section highlights overall key takeaways for individuals and agencies that are planning or seek to plan value capture projects. It summarizes the key recommendations that emerged from the peer exchange and profiles noteworthy practices employed by peer agencies and organizations.

Value capture provides financial flexibility to State and local governments. Given the increasing burden on State and local governments to finance large- and small-scale infrastructure projects, value capture tools are arguably some of the most powerful tools at local governments’ disposable to develop new revenues for local infrastructure needs.

When implemented strategically, value capture can increase equitable access to funding and new and/or improved infrastructure for governments and residents. Integrated approaches to value capture strategies are critical to ensuring that the potential financial burdens can be spread more equitably across the multiple stakeholders who benefit from the capital improvements. These stakeholders can include, but are not limited to, taxpayers, property and business owners or tenants, developers, and private investors.

It is advantageous for agencies implementing value capture to be nimble, streamlined, and responsive to changing project elements. Value capture projects may especially benefit from lean teams with expertise implementing value capture, and the internal support to make decisions.

Value capture implementation must adapt to local context and concerns. There is no one-size-fits-all approach for value capture or any one technique.

Collaboration among agencies and the private sector, especially at the regional level, can increase the potential for success of value capture projects. Intergovernmental agreements, where possible, can enable the communication and project management necessary for success. It is important to invest in regular communication and relationship-building between agencies, even when not actively engaged in projects, to set up opportunities for future collaboration. Fairfax County’s partnership with an adjacent county, and CRRMA’s cross-jurisdictional projects are important examples of the collaboration needed to advance regionally beneficial projects.

Public education campaigns about the benefits of value capture projects may be needed. Public sentiment can be a challenge. Agencies may need to invest in open communication methods to educate the public about what value capture techniques are and how they will impact communities.

Thay Bishop, CPA, CTP/CCM

Senior Program Advisor

FHWA Center for Innovative Finance Support

61 Forsyth Street, Suite 17T26

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 562-3695

Thay.Bishop@dot.gov

Stefan Natzke

National Systems & Economic Development Team Leader

FHWA Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

(202) 366-5010

Stefan.Natzke@dot.gov

| First Name | Last Name | Agency |

|---|---|---|

| Raymond | Telles | Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority |

| Elizabeth | Schuh | CMAP |

| Aseal | Tineh | CMAP |

| Gregg | Hostetler | CONSOR Engineers |

| Brent | Riddle | Fairfax County |

| John | Donovan | FHWA |

| Christopher | Hall | FHWA |

| Stefan | Natzke | FHWA |

| Jim | Thorne | FHWA |

| Neil | Adams | Illinois DOT |

| Sam | Beydoun | Illinois DOT |

| Rocco | Zucchero | Illinois Tollway |

| Tom | Rickert | Kane County DOT |

| Scott | Hamwey | MassDOT |

| David | Kralik | Metra |

| Audrey | Wennick | Metropolitan Planning Council |

| Violet | Gunka-Gurgul | RTA |

| A.J. | Nazem | RTA |

| Patricia | Cahill | USDOT Volpe Center |

| Julie | Kim | USDOT Volpe Center |

| Terry | Regan | USDOT Volpe Center |

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) EDC-5: Value Capture

Agenda for Illinois Value Capture Technique

Dates: September 17-18, 2019

Exchange Host: Illinois DOT & Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP)

Exchange Location: CMAP, 233 South Wacker Drive, Suite 800, Chicago, IL

Length of Exchange: 1.5 days

Value Capture Peers:

Subject Matter Expert: Julie Kim

Format:

Purpose of the event:

| Time | Topic | Lead Presenter |

|---|---|---|

| 8:30 a.m. |

Welcome and Overview:

|

Terry Regan (Facilitator) Erin Aleman , CMAP Executive Director FHWA Illinois Division representative Stefan Natzke, FHWA |

| 8:50 a.m. | IDOT and CMAP overview of current activities and desired outcomes for the peer exchange |

Sam Beydoun, IDOT Elizabeth Schuh, CMAP |

| 9:15 a.m. |

Value capture techniques and facilitated discussion

|

Julie Kim, Subject Matter Expert |

| 10:00 a.m. | Break | |

| 10:15 a.m. |

Value Capture Enablers: Tax Increment Financing and Transportation Reinvestment Zone

|

Terry Regan (Moderator) Julie Kim, SME Elizabeth Schuh, CMAP Raymond Telles, CRRMA |

| 11:45 a.m. | Lunch | |

| 12:30 p.m. |

Special Taxes and Fees (Special Assessment Districts, Improvement Districts, Transportation Utility Fees)

|

Terry Regan (Moderator) Julie Kim, SME Brent Riddle, Fairfax County |

| 2:00 p.m. | Break | |

| 2:15 p.m. |

Developer Contributions (Impact Fees, Other In-Lieu Fees, Negotiated Exactions)

|

Terry Regan (Moderator) Julie Kim, SME Gregg Hostetler, Consor Engineering Scott Hamwey, MassDOT |

| 3:45 p.m. |

Wrap-up and charge for day 2

|

Terry Regan (Facilitator) |

| 4:30 p.m. | End of day 1 | |

| Time | Topic | Lead Presenter |

|---|---|---|

| 8:30 a.m. |

Welcome and Overview of the Day Facilitator welcomes attendees, reviews the key take aways from Day 1 and provides context for Day 2 |

Terry Regan (Facilitator) |

| 8:45 a.m. |

Joint Developments and Others Tools Based on Development Rights and Entitlements

|

Terry Regan (Moderator) Julie Kim, SME Scott Hamwey, MassDOT |

| 10:30 a.m. | Break | |

| 10:45 a.m. |

Discussion, Identification of Key Take Aways, and Next Steps

|

Terry Regan (Moderator) |

| 12:00 p.m. | Wrap-up & Follow-up Actions | Terry Regan (Facilitator) |

| 12:30 p.m. | Adjourn | |

Provided by Julie Kim, SME.

| Category | Technique | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Developer Contributions | Impact Fees | Fees imposed on developers to help fund additional public services, infrastructure, or transportation facilities required due to the new development. |

| Negotiated Exactions | Negotiated charges imposed on developers to mitigate the cost of public services or infrastructure required as a result of the new development. | |

| Transportation Utility Fees | Transportation Utility Fees | Fees paid by property owners or building occupants to a municipality based on estimated use of the transportation system. |

| Special Taxes and Fees | Special Assessment Districts | Fees charged on property owners within a designated district whose properties are the primary beneficiaries of an infrastructure improvement. |

| Business Improvement Districts | Fees or levies charged on businesses within a designated district to fund or finance projects or services within the district's boundaries. | |

| Land Value Taxes | Split tax rates, where a higher tax rate is imposed on land than on buildings. | |

| Sales Tax Districts | Additional sales taxes levied on all transactions or purchases in a designated area that benefits from an infrastructure improvement. | |

| Tax Increment Financing | Tax Increment Financing | Charges that capture incremental property tax value increases from an investment in a designated district to fund or finance the investment. |

| Joint Development | At-grade Joint Development | Projects that occur within the existing development rights of a transportation project. |

| Above-grade Joint Development | Projects that involve the transfer of air rights, which are development rights above or below transportation infrastructure. | |

| Utility Joint Development | Projects that take advantage of the synergies of broadband and other utilities with highway right-of-way. | |

| Naming Rights | Naming Rights | A transaction that involves an agency selling the rights to name infrastructure to a private company. |

| BID | Business improvement district |

|---|---|

| CID | Community improvement district |

| CM/GC | Construction Manager/General Contractor |

| CMAP | Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning |

| CRRMA | Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority |

| CTA | Chicago Transit Authority |

| EDC | Every Day Counts |

| FHWA | Federal Highway Administration |

| FHWA HEP | Federal Highway Administration Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty |

| IDOT | Illinois Department of Transportation |

| LID | Local improvement district |

| MassDOT | Massachusetts Department of Transportation |

| MBTA | Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority |

| MOU | Memorandum of understanding |

| RTA | Regional Transportation Authority |

| SME | Subject matter expert |

| TDD | Transportation development districts |

| TFIA | Transit Facility Improvement Areas |

| TID | Transportation improvement districts |

| TIF | Tax increment financing |

| TRZ | Transportation reinvestment zones |

1Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, Transit Value Capture Analysis for the CMAP Region, December 2010,https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/27573/Value-Capture-Analysis_12-10-2010.pdf/622b876a-2eb4-4a89-bb02-5724e97f8c89; Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, Transportation Value Capture Analysis for the CMAP Region, June 2011, https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/27573/VC-Final-Report_7-26-11-Executive-Summary.pdf/5efa8c6f-da3b-4fe8-8a61-33d322850a01.

For additional information, please contact:

Stefan Natzke