TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

As previously mentioned, some public goods and services generate benefits for an entire community, and no property receives greater advantage over another as a result. Some public goods and services benefit only some properties. Creating a tie-in to a municipal water and sewer line benefits only the property receiving the connection. And some public goods and services benefit the general community while also providing additional benefits to some properties. Examples include, but are not limited to, highway interchanges, transit stations, irrigation and flood control districts, and municipal parking facilities.

The types of benefits created (general or specific), their magnitude, and their geographic distribution depend on both the type of public infrastructure being provided and the economic and geographical context within which it is being provided. For example, building an underground rail transit system in the middle of an isolated rural cornfield will provide neither community benefits nor specific benefits to individual parcels. Indeed, such a project is likely to destroy perfectly good cropland without replacing it with anything else of value. So, as much as some might desire a list of infrastructure projects along with the types, magnitude, and extent of benefits produced by each, no such list can be produced outside of a particular geographic and temporal context.

In the context of creating special assessments, individual properties receive specific benefits from infrastructure projects only to the extent that they receive benefits that are greater than or different from those benefits available to all properties generally. This can be measured by subtracting a property’s land value before infrastructure improvement from its value afterwards. If the percentage increase in value is greater than the average percentage increase in land value for all properties (or if the percentage reduction in value is less than the average percentage reduction in land values for all properties), then there could be a reasonable assumption that the property received a special benefit.45

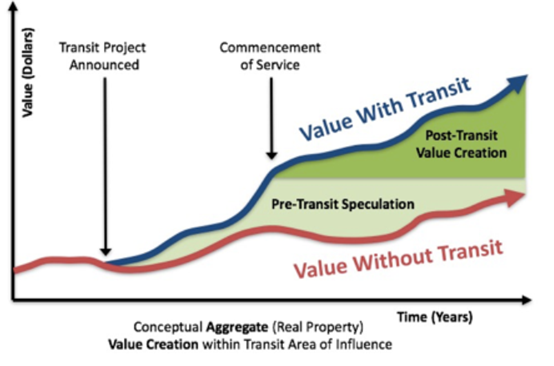

Determining an increase in property value resulting from an infrastructure improvement entails selecting the appropriate time period for the “pre-improvement” measurement. Figure 1 represents value creation for a transit project, but this same scenario could play out for other types of infrastructure improvements as well.

1. Illustration of Value Creation 46

The key point illustrated here is that project-related land value uplift might begin with the announcement of the project.47 Measuring value uplift after project completion misses a significant amount of project-related land value creation.

To the extent that specific and direct benefits to individual properties are created, these benefits are often related to the proximity of benefiting properties to the infrastructure being created or improved.

To the extent that specific and direct benefits to individual properties can be expected in proximity (as measured by time or distance) to an infrastructure improvement, a district could be created for all benefiting properties within such proximity.

To establish a special assessment, a determination or finding is made to establish that specific and direct benefits are received by properties within a defined proximity to new or improved infrastructure.

The most difficult part of the process is to establish a boundary for a special assessment district. Properties within the district’s boundary are deemed to receive a specific and direct benefit (and are therefore liable for a special assessment fee), whereas properties outside the district’s boundary are deemed not to receive a specific and direct benefit (and are therefore exempt from a special assessment fee). If care is taken to avoid conflicts of interest, real estate professionals (i.e., appraisers, brokers, and lenders) can provide market-based information regarding the geographic extensiveness of special benefits generated by various infrastructure projects.

If identifiable properties receive a specific and direct benefit in excess of the benefits received by the general public, the basis for establishing a special assessment could be related either to the cost of the improvement or to the benefit received by the landowner. These two approaches will be discussed below. Regardless of whether the assessment is based upon “cost” or “benefit,” the assessments levied may not exceed the benefit received by each property.48 Any such excess liability could be challenged as a “taking.”

A jurisdiction wishing to recover a portion of its costs from properties receiving direct and specific benefits selects a method to determine how to apportion this cost among the benefiting properties. Several methods are discussed below regarding how each property contributes to the cost of the project.

One approach assumes that all benefiting properties should bear an equal proportion of the costs incurred and therefore should pay the same fee. This could be accomplished by establishing a fee for specific activities, such as connecting individual properties to municipal water and sewer pipes.

The cost of an area-wide project could be divided by the number of properties being served. For example, if street lights are provided to an area, the project costs could be divided by the number of properties within that area.

Another approach is that each property should pay its fair share of the cost, but that each property’s share might be different.

When sidewalks are being built, curbs and gutters being installed, or lanes are being paved, a primary cost variable is distance. Some lots are wider than others and therefore have more “frontage” across which new infrastructure must be provided. Therefore, total costs might be divided by the number of linear feet to establish a cost per linear foot. This cost per linear foot could then be multiplied by the number of front feet for each property to determine each property’s fee.

For corner lots, whose frontage distance might be double that of other typical nearby lots, a determination could be made about the appropriateness of modifying the front-foot basis for all corner lots in recognition that corner lots might not necessarily receive twice the benefit from the infrastructure being provided or improved. The city of Reno, Nevada, for example, provides a 50 percent reduction in cost for the non-address frontage for single-family homes on a corner lot. However, apartment buildings and commercial buildings pay full cost.49

If a project was to control or collect stormwater runoff, it might be determined that larger lots (or lots with greater amounts of impervious surface) would generate more stormwater and therefore should pay more accordingly. Thus project costs could be divided by the number of square feet of total land area (or the square feet of all impervious surfaces such as roofs, driveways, patios, etc.) and then multiply this per-square-foot cost by the number of applicable square feet for each property.50

A jurisdiction wishing to recover a portion of its costs from properties receiving direct and specific benefits also selects a method to determine how to apportion this cost among the benefiting properties. Several methods are discussed below regarding how each property benefits from the project.

To the extent that transportation infrastructure provides a site with greater access to jobs, stores, education, recreation, employees, customers, etc., this accessibility enhances the productivity of that site and thereby enhances the benefits of owning it. The value of land reflects the benefits that people expect to receive from owning it. Therefore, to the extent that transportation (and other) infrastructure enhance the benefits of site ownership, they enhance its value. 51

On the other hand, some public facilities such as airports, highways, and sewage treatment plants can create unpleasant noise or odors that can diminish the value of land—at least for certain purposes. Thus, airport noise might diminish the value of nearby land for residential purposes but increase its value for purposes related to air freight and air travel. So the interplay between zoning and infrastructure amenities and nuisances is critical in determining whether land values will increase or decrease.

Because land value reflects the net of advantages and disadvantages conferred by infrastructure to particular sites, some jurisdictions may conclude that land value is an appropriate basis for funding the infrastructure, which creates a significant portion of site value.

It is important to understand that land values and prices reflect expected benefits of ownership.52 Thus, measuring increases in land value after a new infrastructure project has been completed might miss a substantial amount of the land value uplift, much of which may have occurred earlier when the project was being discussed and planned.53 Similar increases in land value would also occur if zoning or other development regulations were changed to enhance the intensity or value of subsequent development.54 Land value increases would begin as soon as potential property owners felt that increased development permission was likely. This crystalizes the importance of having value-capture mechanisms in place before there is any expectation that a significant infrastructure project or up-zoning will proceed.

If a new highway interchange provides enhanced accessibility to two adjacent sites, the land value created by this infrastructure improvement is the same regardless of whether either or both sites are developed or vacant. Nonetheless, some jurisdictions contend that infrastructure enhances “property value,” and they make no distinction between publicly created land values and privately created building values. In these instances, special assessments are created by applying an additional rate (percentage) to the total property assessment instead of applying it to only the land value.

As mentioned, States have authority to levy property taxes55 and to levy special assessments.56 However, counties, parishes, townships, cities, towns, or other governmental entities cannot levy property taxes or special assessments unless a State delegates these powers to those jurisdictions. And once a governmental entity has the authority to levy a property tax or a special assessment, it would enact implementing ordinances to employ these powers in particular instances.

States wanting component jurisdictions to be able to implement special assessments will delegate this power through enabling legislation. This legislation would indicate which levels of government are authorized to implement special assessments, the circumstances that make special assessments appropriate, and any other conditions or criteria limiting the exercise of this power. For example, the legislation could address:

If the State or other jurisdiction authorized to levy a special assessment wishes to implement such a levy, an implementing ordinance would need to be enacted by that jurisdiction. This ordinance would note the jurisdiction’s authority to levy a special assessment and indicate the degree to which the prerequisite conditions for such a fee have been met and how, pursuant to conditions and criteria in the authorizing legislation, a particular special assessment would be levied. These details typically would include:

Both the authorizing and implementing legislation would be introduced, considered, and voted upon according to the laws and customs for enacting legislation in a particular jurisdiction. This includes notifying the public and providing them with an opportunity to review the proposed legislation and to comment upon it prior to a vote.

Typically, as part of the legislative process, hearings are held to obtain input from the affected public. Persons who are interested in the provision of public infrastructure generally, and those who could be subject to the fee in particular, are typically afforded an opportunity to testify about proposed legislation to convey their support or opposition, or to propose changes.

Pursuant to the laws and customs for adopting legislation, the legislative and executive branches of a jurisdiction may enact a special assessment authorizing legislation or implementing ordinances.

Once implementing legislation has been enacted, the agency administering the infrastructure project and the finance and revenue agency coordinate project funding with establishment of an account to receive special assessment fees. Affected property owners are notified that the special assessment fee has been enacted and will be collected as a surcharge to their regular property tax payments. Certain administrative and regulatory procedures (e.g., finalization of an assessment roll) might be required and might entail their own requirements for notice and hearings or appeals.

If a special assessment is established to fund a capital project, termination is likely to occur when specified capital costs (such as payment of debt service on a bond) have been completed. Alternatively, if the special assessment funds ongoing operating costs, there might be a sunset or termination date with an option for renewal of the special assessment.

As mentioned above, the most traditional special assessment practice entails a jurisdiction imposing a special assessment to fund a capital project undertaken by one of that jurisdiction’s agencies. Thus the assessment is collected by and spent by a jurisdiction in pursuit of a duly approved and budgeted project. However, there are variants whereby special assessments are collected by a jurisdiction but established and administered by another body. A few of these variants are discussed below.

A BID is an entity authorized by a State and created by a local government pursuant to that authorization. However, it is run by private property owners to provide enhanced services in the public realm. These service enhancements might include more frequent pickup of street litter, landscaping, hospitality services, marketing, wayfinding signage, or public entertainment.

The public sector might not be able to provide this level of service throughout the jurisdiction, and might conclude that providing additional services within a small area would be inequitable. On the other hand, if some private landowners within a neighborhood agreed to fund these additional services and other landowners in this neighborhood did not contribute, the noncontributing landowners would receive the benefits without paying the costs.

To avoid this “free rider” problem, some jurisdictions provide a process whereby property owners can elect to create a BID, select its directors, and establish a mandatory fee to be collected as a special assessment by the jurisdiction in addition to (and as part of) its regular property tax collection process. However, revenues from this additional mandatory fee are not spent by the jurisdiction that collects them. Instead, the BID fee revenues are distributed to and administered by the BID directors. Thus, BIDs are created by and accountable to property owners within their boundaries.57

Typically, BIDs engage primarily in operating services such as those mentioned above, although some landscaping and signage activities are considered capital projects. The scope and character of BID activities will be determined by State authorizing legislation, local implementing legislation, and the bylaws of each BID.

CIDs, as established in Georgia and Missouri, are similar to BIDs because they are typically initiated and administered by developers or commercial property owners. However, their fundraising and planning powers are more robust, akin to SSDs, allowing them to take on significant capital infrastructure projects.58

SSDs are independent elected public bodies with enumerated taxing and administrative powers established to fulfill a function, or set of related functions, not being handled by existing jurisdictions. These might include street lights, drainage, sanitation, water and sewer services, power generation and distribution, or landscaping of public spaces.

In some cases, properties within an SSD might span multiple jurisdictions. For example, a flood control district, defined by a watershed, could include several jurisdictions. Although some school districts are organized like SSDs with public elected boards empowered to raise taxes and spend revenues for facilities and teachers, they are classified as “school districts” and not as “special service districts.”

States might establish criteria for creating SSDs. A special election by the voters within the designated area is typically necessary to create an SSD. Often, they are created by developers when the developer is the only voter within the designated area. Once established, they are accountable to all residents within the SSD. In California, they are called community facilities districts or Mello-Roos districts (after the names of the State legislators who created them in the 1980s).59 Due to Proposition 13, community facilities districts may not use the value of the properties as a basis for calculating the fee. Instead, they could divide the cost of the facility or service by front footage (good for sidewalks or water and sewer lines) or by the number of properties served if it appears that each property receives roughly the same benefit (e.g., street lighting).60

45 FHWA. “Value Capture Implementation Manual.” Section 6.1.4. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/value_capture/resources/value_capture_resources/value_capture_implementation_manual/ch_6.aspx

See also Miller Nash Graham & Dunn, “The Seattle Waterfront Local Improvement District” (October 2013) at http://www.millernash.com/the-seattle-waterfront-local-improvement-district-lid-10-30-2013

46 Page, S., Bishop, W., and Wong, W. (2016). “Guide to Value Capture Financing for Public Transportation Projects,” TCRP Report 190, Figure 2, page 5. See also Center for Transit Oriented Development, “Capturing the Value of Transit,” November 2008, Figure 3-1, page 13.

47 Rybeck, R. (2004). “Using Value Capture to Finance Infrastructure and Encourage Compact Development,” Public Works Management & Policy Journal, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 249–260. See note 15, p. 259.

Miller Nash Graham & Dunn, Attorneys at Law, “The Seattle Waterfront Local Improvement District (LID),” October 30, 2013, https://www.millernash.com/the-seattle-waterfront-local-improvement-district-lid-10-30-2013

49 City of Reno, NV, “What happens if I own a corner lot? Will I receive a full assessment on both street frontages?” https://www.reno.gov/government/departments/public-works/capital-projects/faqs

50 In the case of assessments to handle or treat stormwater, liability based on the area of impervious surfaces could be offset, at least partially, by property owner actions (installation of rain barrels, rain gardens, etc.) to reduce stormwater runoff. The District of Columbia has such a discount program. See https://doee.dc.gov/riversmartrewards

51 See Lari and others, “Value Capture for Transportation Finance.” Report 09-18 (University of Minnesota Center for Transportation Studies, 2009).

52 Samuelson, P. (1973). Economics, Ninth Ed., (McGraw Hill) Chapter 28, “Pricing of Factor Inputs: Land Rents and Other Resources,” pp. 557–568.

53 See “Taxpayers risk ‘missing out’ on share of land value surge near new projects” The Sydney Morning Herald, Sept 26, 2020, at https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/taxpayers-risk-missing-out-on-share-of-land-value-surge-near-new-projects-20200924-p55ypo.html. Similarly, prior to the completion of the NoMa-Gallaudet U Metro Station (discussed in Chapter 9 below), Washington, DC, real estate broker Mark Mallus noted that property values within the vicinity of the proposed station had already risen significantly. Given the region’s congested roads and the economic opportunities created at centrally located stations, the mere expectation of future access to Metro can have this effect.

54 Upzoning, by itself, does not enhance land value. Instead, there must be economic demand for development that is prohibited or constrained by existing zoning. Only then will enhancing development permission lead to increases in land values and prices.

State-by-State Property Tax at a Glance. https://www.lincolninst.edu/research-data/data-toolkits/significant-features-property-tax/state-state-property-tax-glance. Significant Features of the Property Tax. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and George Washington Institute of Public Policy. Property Tax at a Glance.

56 Special assessments are authorized in all 50 States either under explicit enabling legislation or by State constitutional provisions. See “Special Assessments: An Introduction,” Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/fact_sheets/value_cap_special_assessments.aspx

57 Washington, DC, contains several business improvement districts. To coordinate some of their activities, they have created a DC BID Council. You can learn about the Council and about individual BIDs at https://www.dcbidcouncil.org/aboutdcbids.

58 See https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/value_capture/defined/community_improvement_districts.aspx

See California Debt and Investment Advisory Commission, California Mello-Roos Community Facilities Districts Yearly Fiscal Status Reports 2017–2018, https://www.treasurer.ca.gov/cdiac/reports/M-Roos/2018.pdf

Proposition 13 is embodied in Article XIII A of the Constitution of the State of California. Section 4 of Article XIIIA prohibits special districts from imposing ad valorem taxes on real property or a transaction tax or sales tax on the sale of real property.