TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

As shown in Figure 4, agencies/sponsors can employ a number of tools to reduce the impact of economics shocks in value capture funded projects.

| Symbol | Tool |

|---|---|

|

Analyze downsides |

|

Overcollateralize |

|

Build in reserve funds |

|

Collect revenues before project start |

|

Reduce early year cashflow pressure |

|

Develop projects by phase or extend development period |

|

Backstop projects with creditworthy sources |

Figure 4 . Summary of Tools to Mitigate Economic Shocks

Public agencies and project sponsors should carry out downside analyses and structure their funding plan accordingly. While project planners hope downside scenarios do materialize, unfortunately, as COVID-19 demonstrates, the reality is that they do. To plan for the worst case, it is important during project planning to run several downside scenarios on value capture revenue projections. Conducting this analysis will help public agencies and project sponsors understand what funding mechanisms need to be in place to ensure the project has enough cash flow to survive periods of stress. Mitigation measures for handling such downside scenarios are discussed in the remaining sections of this chapter.

Box 2: The Assembly Project in Doraville, GA Demonstrates Importance of Conducting Downside Analysis 24, 25

The Assembly Project, an adaptive re-use project that features commercial, residential, entertainment, and a filmmaking studio in Doraville, GA, illustrates the importance of conducting a downside scenario. During the planning phase, the scenario analyses showed the need for additional funding sources if the project's primary funding sources–tax increment funds, a Payment in lieu of Taxes (PILOT) fund (a payment made by a non-profit entity for public services instead of paying property taxes), and additional taxes levied on commercial property owners in the defined district–failed to materialize at projected levels. In this eventuality, a type of special assessment would be levied as a backstop. During the COVID-19, the project's primary funding sources did not meet projections and the Assembly project drew on $2.8M of special assessments.

Beyond shocks to funding, public agencies and project sponsors should prepare for and be flexible in the face of tightened financial markets. The need for financing flexibility was evident in the development of Denver Union Station, which occurred during the GFC. The Denver Union Station Project Authority (DUSPA) originally assumed a financial plan consisting of tax-exempt securities to be sold in financial markets. Unfortunately, due to the GFC, the tax-exempt markets were shied away from this type of riskier credit. DUSPA then turned to Federal financing–the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) and the Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) loan programs. This flexibility in financing sources allowed the project to be successfully completed, and the loans were repaid ahead of time.

Default risk can be reduced by increasing the debt service coverage ratio (DSCR) and/or the value-to-bond ratio in a SAD financing. A DSCR measures cash that is available to pay for debt service in a certain period. A value-to-bond ratio or value-to-lien ratio measures the assessed values in the respective SAD to the principal amount of the bond or loan. For a DSCR and value-to-bond ratio, higher ratios give lenders greater comfort in the event that taxes or fees are inadequate and/or the assessed value of properties does not grow as anticipated. 26 Including special assessments, Mosaic’s DSCR is over 2.00 in the base case (Scenario A). This is generally considered a healthy DSCR level, as discussed in Appendix 1.27 By overcollateralizing, cash sponsors commit additional revenues to be available to pay debt service. The same is the case for limiting the size of the loan, which requires sponsors to find other funding sources, such as grants or their own resources, to make up the difference.

Public agencies and project sponsors should consider reserve funds and other resources to mitigate real estate-related volatility. These are funds that can consist of reserves that the agency/sponsor establishes using project revenues and other resources to which they are legally entitled. Setting aside these funds may be at the agency/sponsor’s discretion and not necessarily a requirement of the financing.

The agency/sponsor could also establish a fund that is incorporated into the financial documents. In the case of Mosaic in Appendix 1, the sponsor entered into a “Memorandum of Understanding” with Fairfax County, in which the project was located, to allow it to establish a “Surplus Fund” which would consist of special assessments that were in excess of the debt service requirements in the period in question. 28 The sponsor was allowed to maintain a Surplus Fund of 1.50x of the periodic debt service and use such monies to repay itself for debt service that they had covered over the last two years should incoming tax increments not be adequate. However, in Mosaic’s case, the Surplus Fund was technically not pledged as collateral to repay interest on the Mosaic bonds.

These reserve funds are in addition to a standard debt service reserve fund (DSRF) that is typical of municipal bonds. A DRSF is usually funded at the time of bond issuance at:

… an amount that is equal to the least of:

(i) The maximum amount of principal and interest due on the Bonds in the current or any future fiscal year, or

(ii) 10 percent of the original stated principal amount of the Bonds, or

(iii) 125 percent of the average annual amount of principal and interest due on the bonds in the current or any future fiscal year. 29

The DSRF is usually pledged as collateral to repay bonds, as is the case in Mosaic.

Public agencies and other project sponsors can begin to collect revenues and/or tax increments before project start or before project financing, thereby creating a reserve and demonstrating to lenders the adequacy of pledged revenues. A good example of this is the Parole Town Center project $8.3M of interchange and improvements to Federal, State of Maryland, and local roads in Parole, Maryland. To fund this project, a 2.4-square-mile TIF district was established that included major commercial real developments. The district was established three years prior to financial close in 1999. Between the establishment of the district and financial close, the property valuations within the district grew by a rate of over 6 percent per year, resulting in $500,000 in the “Tax Increment Fund” that would be available to fund the over $1M in debt service in the next year.30 This “on-the-ground” evidence was valuable to establish a revenue track record for lenders.

To reduce pressure on cash flows in early years of a project, agencies/sponsors can employ financing techniques that reduce or delay the payment of debt service. These techniques come in a number of forms, including:

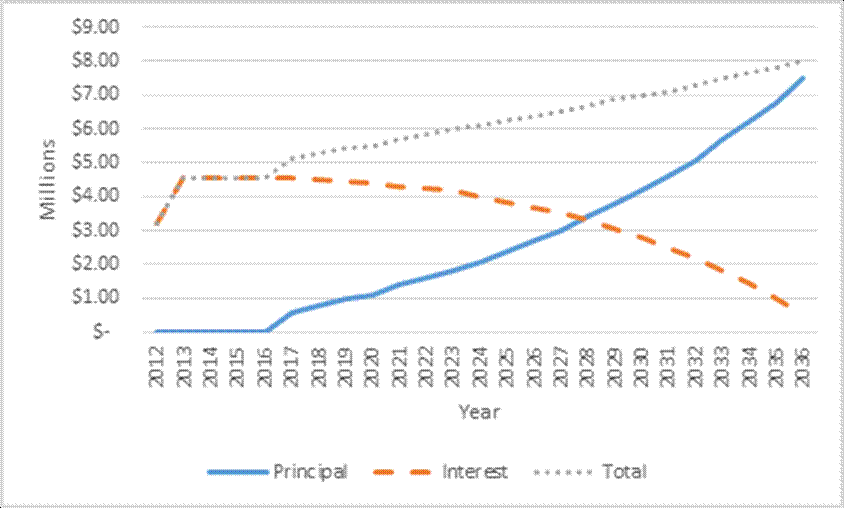

Figure 5. Mosaic Project Total Debt Service Payments 2012-2036 (in $M)32

Public agencies and project sponsors may want to build projects in phases and/or provide additional development flexibility. Developing projects in phases allows the project to be built as public budgets or debt capacity to raise financing becomes available. Doing a project this way might take longer. However, as the Colorado E-470 project shows, this approach helps to eventually complete the project even if some portions are delayed.

The Colorado E-470 project was built in segments in response to economic issues that affected toll and value capture-related revenue projections. E-470 is 47-mile, toll highway that forms approximately half of a beltway around the Denver metropolitan region. Constructed in the 1990s, the first segment was financed before the Persian Gulf War, savings and loan crisis, and the early 1990s economic recession. The subsequent three segments were delayed as both the configuration of the project and its financial plan were restructured. This included: 1) moving the project closer to population centers to increase the value capture and toll funding sources and 2) obtaining loans from local jurisdictions and Colorado DOT. The project was funded with “Highway Expansion Fees,” vehicle registration fees collected within E-470’s boundaries, and tolls. Highway Expansion Fees were a type of impact fee, one-time fees paid when a building permit was issued for new construction within 1.5 miles of the E-470 centerline, varying by property type and proximity to E-470. Vehicle registration fees were additional fees collected within the boundaries of the county jurisdiction through which the highway passed, similar to a sales tax district. These value capture sources helped sustain the project during the early years until toll revenue grew to financially sustainable levels.33

Public agencies and project sponsors should consider creditworthy funding sources such as a secondary pledge or backstop. In the case of Mosaic (see Appendix 1), the project funding plan included a special assessment as a funding backstop. In the worst-case scenario, $40M in special assessments would have been required. This worst-case scenario did not materialize and TIF revenues exceeded expectations. However, as in the Assembly case, referenced in Box 2 above, these creditworthy backstops are sometimes needed.

In the example of Mosaic, the sponsor used a SAD to provide strong credit support to the TIF district. As discussed in Appendix 1, Fairfax County could levy special assessments on properties in the district if tax increments were not adequate. The sponsors analyzed several scenarios in which special assessments would be required and made this available to lenders. This analysis included evaluating the impact of the Pandemic on real estate demand at district properties. Mosaic has used other complementary risk mitigation measures to reduce the risk that TIF revenues may not be adequate, including:

Generally, effective engagement across a range of stakeholders can determine the success of transportation projects reliant on value capture funding. This may be even more important in times of economic shock. As the Atlanta BeltLine case, profiled in Appendix 1 demonstrates, strong stakeholder and community support can also help projects remain resilient the face of economic shocks like the GFC or the COVID-19 Pandemic. Focused on engaging the broader community from the start, the Atlanta BeltLine front-loaded highly visible and high-priority improvements. This early success enabled the project to earn community support. Thus, despite the presence of an economic shocks, the project has been able to access additional value capture funding sources. For example, in 2021 during the pandemic, the City of Atlanta was able to approve a Special Services District (i.e., special assessment district) to generate an additional 100 million for the BeltLine trail project to keep it on track.

24Assembly Community Improvement District Assessment Bonds, Series 2017A, Annual Filing, December 31, 2020. CUSIP No. 04539H AB0. P2.

25Ibid.

26Moody’s, “Special Assessment / Special Project Tax (Non-Ad Valorem) Debt,” November 23, 2016, p. 4.

27Municap, “Tax Increment and Special Assessment Report, 2011,” p. 80 in “Mosaic District OS,” 2011.

282011 OS, p. 21

29 2021 OS, p. 20

30 Parole OS, p. 19-23

31Municipal Securities Rulemaking board, “About Zero and Capital Appreciation Bonds,” see: https://www.msrb.org/~/media/Files/Education/About-Zero-Coupon-and-Capital-Appreciation-Bonds.ashx

32“$65,650,000 Mosaic District Community Development Authority (Fairfax County, Virginia) Official Statement (OS),” May 26, 2011, p. 15.

33FHWA, Value Capture: Capitalizing on the Value Created by Transportation, Implementation Manual, 2019, pp. 172-175, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/value_capture/resources/value_capture_resources/value_capture_implementation_manual/ch_4.aspx.